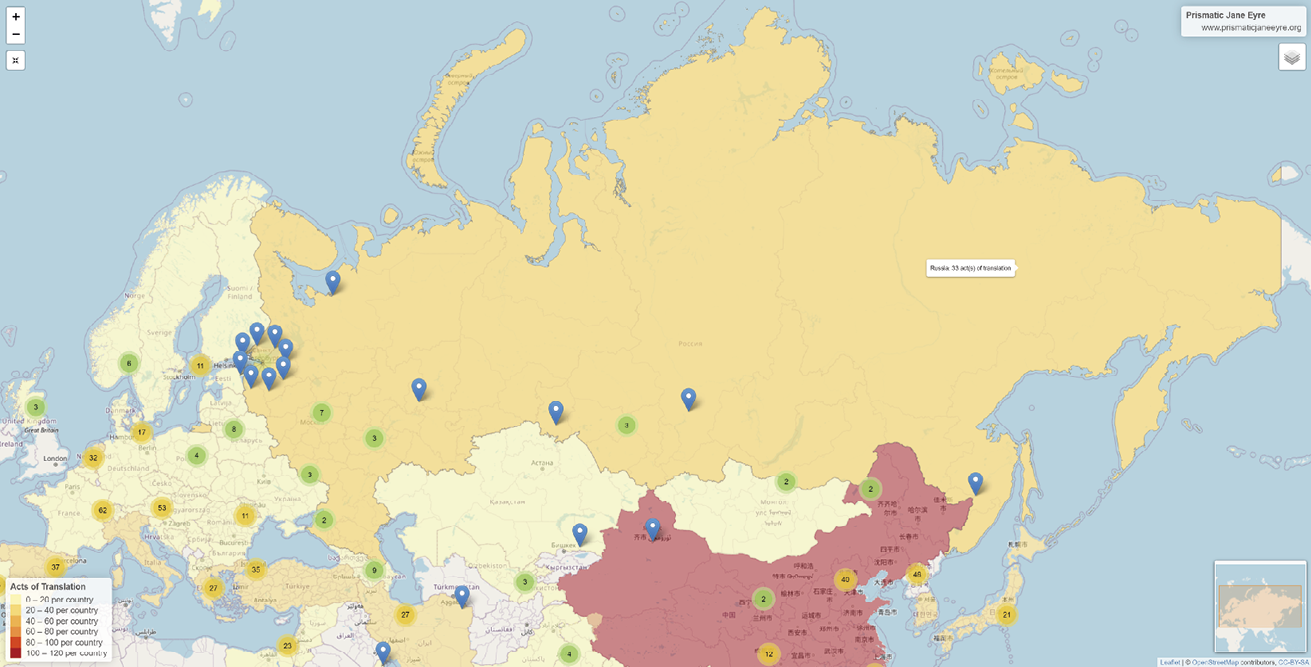

The World Map https://digitalkoine.github.io/je_prismatic_map Created by Giovanni Pietro Vitali; maps © Thunderforest, data © OpenStreetMap contributors

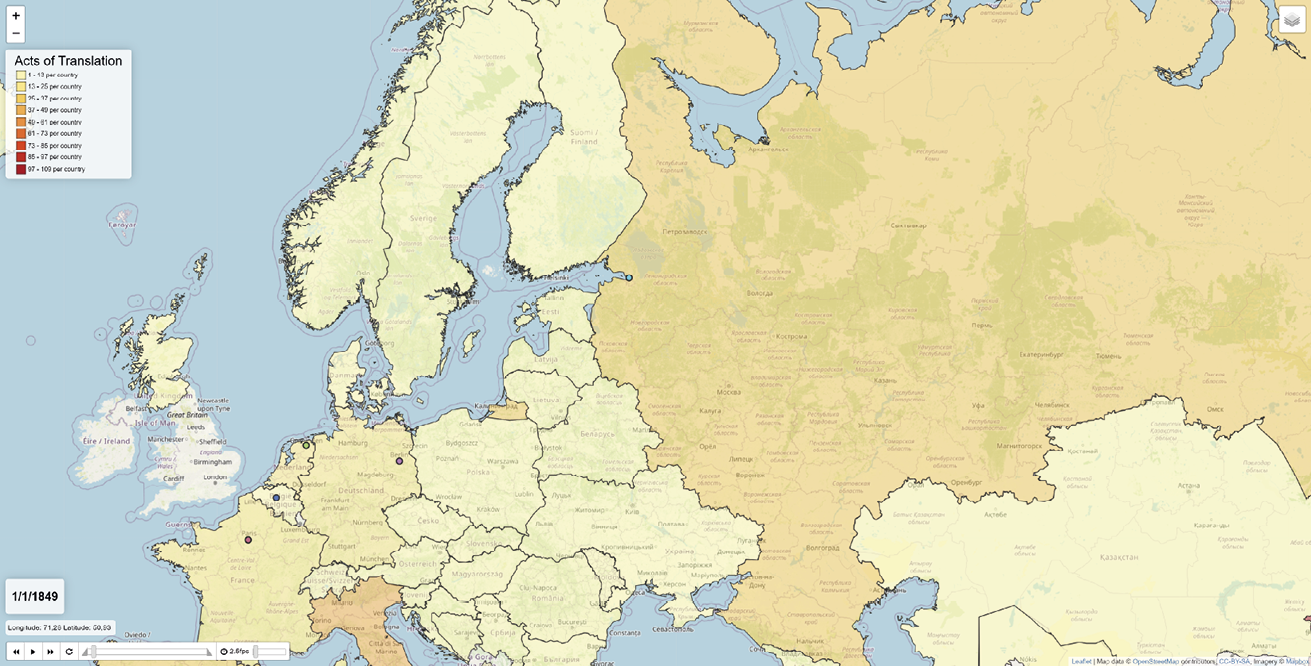

The Time Map https://digitalkoine.github.io/translations_timemap Created by Giovanni Pietro Vitali and Simone Landucci;© OpenStreetMap contributors, © Mapbox

17. Appearing Jane, in Russian

© 2023 Eugenia Kelbert, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0319.25

Introduction1

Few aspects of the novelistic genre reveal the prismatic character of translation variation in a way that is more visible than character description, or more visual. Unlike most aspects of translation, descriptions of appearance rely on a disproportionately small number of well-chosen words destined to form the top of a cognitive iceberg in the reader’s mind. Whenever particular characters are on stage, and often when they are spoken of or otherwise relevant to our interpretation of the story, we cannot but imagine their expressions and gestures, their physical presence. The resulting mental image thus remains an aspect of the reading experience even when the initial literary portrait is very scarce. In other words, appearances, once established, are a silent factor we literally must bear in mind as readers as well as critics, throughout the novel.

Yet how aware are we of how the characters we identify and empathise with, or perhaps detest, would look if we met them in the street? We may not give it much thought, but few readers could, given sufficient artistic skill, draw even the most beloved, intimately known character from a favourite novel off the top of their head. This may explain why many readers watch screen adaptations, a form of semiotic ‘matching’ between distinct systems of signifiers that many critics consider a near-impossibility.2 For an avid reader, the book, as a rule, comes first, and the best adaptation is secondary. Yet most readers will flock to the cinema to welcome — or criticise — a new Emma Woodhouse, Anna Karenina, or Jane Eyre. ‘Emma was nothing like Emma,’ they will say afterwards, ‘though she is the right type.’ Such analysis, paradoxically, informs the reader of their own vision of the character. If it happens to coincide with that offered by the film, the adaptation acts as a visual aid that helps reaffirm that vision. And what if it does not? Then the jarring sensation becomes, in itself, a way to flesh out ‘the reader’s own personal idea’.3

There are good reasons for the combination of precision and vagueness in how we imagine a literary character. As Heier points out, gaps in key information about character appearance form a major step in the evolution of the literary portrait: as the genre developed, the detailed descriptions we find in Balzac or Dickens were increasingly replaced by ‘mere signals and meagre suggestions by which the portrait is to take shape’.4 Once the traditional at-length portrait goes, ‘the reader depends on his own aesthetic sensitivities; he is left with his own imagination to complete the full portrait. Although this manner may initiate a highly sophisticated aesthetic process in the reader’s mind, one no longer is dealing with the portrait created by the author’.5 As the modern literary portrait becomes a literary sketch, the author’s job is no longer to supply an image to the reader, but rather to direct the reader’s imagination with well-chosen strokes. The actual process that leads the director to a casting decision, and the reader to the impression that ‘they got it completely wrong,’ is a matter of cognitive poetics and part and parcel of the reader’s mental model of a given character.6 Brontë, whose work is contemporary with Dickens’s greatest novels even if he claimed to have never read it,7 seems to have anticipated this trend. Indeed, her work may have contributed, as this analysis helps to demonstrate, to the way it came to develop.

When it comes to Jane Eyre, the pieces of this visual puzzle are handed out very sparingly indeed.8 Edward Fairfax Rochester, for example, is of medium height, has a broad chest, and is supposedly unattractive. But does he have facial hair? In fact, Rochester has ‘black whiskers’, but we only glean that bit of information when Jane sketches his portrait when visiting Mrs Reed, half-way through their courtship.9 How was the reader to imagine his face until then? What happens to that mental representation once this information is revealed? What is more, Russian translators of Jane Eyre interpret this gem of insight very differently: two abridged or rewritten versions skip it altogether, and these Rochesters may as easily be clean-shaven as wear a beard, three more adorn him with sideburns, and only one — but the one that reached by far the widest readership — gives him a moustache. The looks produced as a result of the omission or different interpretations of the word ‘whiskers’ by the given translator can therefore differ widely. This also affects screen adaptations: a Rochester with sideburns is inevitably less relatable than one that wears a kind of facial hair we associate with our own times.

When it comes to Jane, the effects of such translation nuances can become especially complex. She is, on the one hand, a romantic heroine and the object of the disenchanted protagonist’s passion, and as such, her looks are of primary importance to the narrative. Like Rochester, she is not attractive, but while a physically unattractive hero carries something of a demonic halo, an unattractive heroine narrator has a different effect entirely. Insofar as the reader (often a female reader) identifies with Jane, her supposed plainness, and the nature of that plainness, not only subverts pre-existing conventions of the genre, but makes her relatable in a new and radical way. Jane has no fairy godmother and never turns into a beautiful princess; instead, she remains herself and wins tangible happiness through sheer personality and self-respect. Unlike the stories of conventional romantic heroines, hers becomes one any reader can aspire to, regardless of their origins or looks. In this respect, the story of Jane and Rochester’s romance as told by the servants (which Jane herself is treated to when she returns incognito) foreshadows the novel’s trace in the popular consciousness: ‘nobody but him thought her so very handsome. She was a little small thing, they say, almost like a child’.10

Jane is, however, not only the protagonist but also the first-person narrator and, for all her introspection, poorly placed to supply a badly needed verbal portrait of herself in the style of an omniscient narrator. While she is a keen observer of others, what we know of her own appearance must come from observers of her as she quotes them, and the resulting image is inevitably sketchy, an elusive Picasso-like sketch made from a dozen different perspectives. It relates as much, and often more, information about these perspectives as about the heroine. In this, the reader is only offered two crutches to lean on: the consensus multiple characters seem to share of what beauty or the lack of beauty seems to be, and the equally shared notions of phrenology and physiognomy the novel’s characters refer to, again, as a shared truth.11

Ultimately, neither source of objectivity proves very reliable. Rochester calls Jane a ‘changeling — fairy-born and human-bred’, and while her personality makes her seem like a pillar of stability to his temperamental and whimsical self, the unseizable quality at the protagonist’s core extends to the more technical ways her character is crafted.12 The fact that she is the teller of her own story, the observer as well as the focus of attention, makes the novelist’s — and the translator’s — task all the more delicate.

This essay, then, focuses on character description as an exploration of the way prismatic processes permeate even the most fundamental aspects of a novel in translation. It traces the way Jane’s appearance refracts in the novel’s transition from English to Russian, from the first Russian translation, completed only two years after the novel’s publication, to its last, and sixth Russian version, published as recently as 1999. While I explore character description in Jane Eyre more generally as a case study in Bermanian networks of signification elsewhere,13 Jane’s appearance is a special case that deserves closer scrutiny. This case study highlights the nuances of translating both narrative voice and characterisation in a setting where the stakes of individual word choices in translation are particularly high, not only for what is but also for what is not put in words.

Of the six Russian incarnations of Jane Eyre, three were published in the nineteenth century and three more in the twentieth. The first four are pre-revolutionary and use the old spelling system, later reformed by the Bolshevik government; two of these are full versions of the novel and two more are rewritten or abridged. The first is by Irinarkh Vvedenskii, a brilliant translator and early translation theorist, who gave Russian readers vivid and highly readable (though sometimes embellished by his own — often very tasteful — improvements) versions of Dickens and Thackeray, as well as Brontë.14 His reaction to Brontë’s novel was immediate: the first Russian translation came out as early as 1849. Curiously, Vvedenskii later claimed that, in contrast to his heartfelt respect and love for Dickens and Thackeray, he had, for reasons he would keep to himself, neither love nor respect (‘вовсе не люблю и не уважаю’15) for the ‘English governess’ who wrote the novel and therefore had no qualms in improving the text to suit his own taste: ‘The novel “Jane Eyre” was indeed not translated but rather refashioned by me’ (‘Романъ “Дженни Эйръ” дѣйствительно не переведенъ, а передѣланъ мною’).16

The second translation, by Sofia Koshlakova (1857), is done from the French adaptation of Jane Eyre by Paul-Émile Daurand Forgues, published under the pseudonym of Old Nick (1849).17 This version stands out in that the novel is not only abridged considerably, but also recast as an epistolary novel where Jane is telling her story to a female friend called Elizabeth. The choice to work from this early adaptation may or may not have something to do with the fact that the book was marketed as part of a ‘Library for summer retreats, steamboats and railways’: in 1855, Old Nick’s French text had similarly been re-published by Hachette in its ‘Bibliothèque des Chemins de Fer’ (‘Railway Library’).18 In addition, the Russian public was exposed to early digests or excerpts from the novel.19 The end of the century saw a full retranslation by V. Vladimirov in 1893 (which largely followed Vvedenskii’s), and the twentieth century started off in 1901 with an anonymous abridged version for a youth audience.

Two more translations enter the scene after the Revolution and remain the only ones currently in print. One, by Vera Stanevich, came out in 1950 and became a classic; this was essentially the only version available, in enormous runs sponsored by the State’s considerable publishing and distribution mechanism, until the USSR became a thing of the past.20 Unfortunately, several passages, especially concerning religion, were removed by the Soviet censor,21 and another translator, Irina Gurova, republished this version with the missing parts restored in 1990. Gurova also published her own translation, which differs considerably from Stanevich’s.22 It goes without saying that many things have changed for the Russian Jane over a century and a half of retranslations. Notably, three of the six translators considered changing or adapting the novel to be part of their job description, and all but one version were censored to a lesser or greater degree. From the content of the novel to spelling, the translator’s priorities and the very literary language of the time, we are dealing here with six different books. Focusing specifically on appearance offers a visual and compelling window into these differences.

No Beauty, or Translating Imperfection

Jeanne Fahnestock argues that character description in British letters evolved drastically between the early nineteenth century and the 1860s. In the beginning of this period, the appearance of characters, and especially heroines, was referred to in a cursory fashion, so that a novelist may have noted, for instance, feminine features, beautiful in every respect. Towards, the end, what Fahnestock calls the ‘heroine of irregular features’ takes centre stage, largely under the influence of physiognomy. As the heroines’ features grow less regular and harmonious, the heroines themselves gain license to imperfection and, as a result, also personal growth. This had hitherto been, with few exceptions, the privilege of the hero. In fact, a new ‘aesthetic of the imperfect’ became so much part of the air du temps that by 1868 a popular article declared women with perfectly regular features to be dull.23

Jane Eyre falls squarely in the middle of this period and exemplifies this change: ‘the minutely described heroine has a much harder time being perfectly beautiful; she is often a heroine of irregular features instead’.24 Jane is, indeed, a heroine of irregular features if ever there was one. This makes sense in physiognomic terms: insofar as character is expressed in salient features, asymmetrical by definition, striking personality must be accompanied by irregularity in appearance (with St John the exception that proves the rule). Indeed, Brontë’s motivation behind the novel, as reported by Gaskell, plays out this very drama in her argument with her more conventionally minded sisters, who claimed that only a beautiful heroine could be interesting. ‘Her answer was, “I will prove to you that you are wrong; I will show you a heroine as plain and as small as myself, who shall be as interesting as any of yours.”’25

Jane herself, in her capacity as the story’s narrator, also assumes that appearance and personality are related; for example, living up to St John’s expectations is to her ‘as impossible as to mould my irregular features to his correct and classic pattern, to give to my changeable green eyes the sea-blue tint and solemn lustre of his own’.26 The irregularity of her appearance, however, does not make her a ‘minutely described’ heroine; on the contrary. In fact, we never find out what about Jane’s features is ‘so irregular and so marked’: A prominent nose? A large mouth? Or do her ears stick out? We know Jane is of small stature and has a slight figure, which makes Rochester think of an elf or a fairy when looking at her, but there is little else, particularly when it comes to facial features.27 With her protagonist, Brontë manages to combine early-century vagueness with an aesthetic of the imperfect.

Each translator must then pick a side in terms of where to place Jane on the novel’s elusive scale of physical attractiveness. Jane is not a beauty, granted, and repeatedly contrasted with regular-featured belles such as Georgiana in her childhood and Blanche in her youth. Yet, the opposite of beauty is ugliness, and is Jane actually ugly? Abbott calls her ‘a little toad’ at age ten, St John declares hers an ‘unusual physiognomy’ that ‘would always be plain’, as the ‘grace and harmony of beauty are quite wanting in those features’, Jane’s female cousins are of the opinion that, when in good health, ‘her physiognomy would be agreeable’, and Rochester at one point pronounces her to be ‘truly pretty this morning’.28 Even though she looks unusually happy when this last pronouncement is made and he is a man in love, the image goes badly with extreme bad looks and suggests rather a lack of particular beauty, now made up for by happy emotion.29

Given this fragile balance of points of view in the original, the translator’s seemingly minor decisions lead to significant variation. In some translations, carefully wrought negatives such as ‘you are not beautiful either’ become in Russian nekrasiva — literally, the word means ‘not-beautiful’ but in Russian it is actually much closer to a description of extreme plainness than to a lack of the quality we call beauty.30 If the first translation, by Vvedenskii, keeps to vague expressions such as ‘you are not a beautiful woman either / вѣдь и ты — не красавица’,31 the second by Koshlakova exaggerates the effect consistently. In fact, Koshlakova goes so far as to mention, speaking of the child Jane, her plainness that ‘apparently repelled my relatives / свою некрасивость, по-видимому, отталкивающую близких моих’;32 elsewhere, again, she consistently makes Jane’s looks actively unpleasant. For example, where Rochester tells Jane she is ‘not pretty any more than [he is] handsome’, Koshlakova adds an extra edge to it with ‘nature has been just as unmerciful to your appearance as to mine33 / хоть природа была такъ же немилостива къ вашей наружности, какъ къ моей’.34 The last nineteenth-century translation, by Vladimirov, strikes a somewhat shaky balance between Betsy declaring Jane ‘недурна’35 (not bad-looking, one can even imagine it used to describe someone as being attractive) and ‘некрасива’, that is to say bad-looking. Vladimirov goes further still, for example, in translating ‘features so irregular and so marked’ as ‘черты моего блѣднаго лица неправильны и невыразительны’ (‘that the features of my pale face [were] irregular/incorrect and inexpressive’).36 Suddenly, Jane’s features are the opposite of marked in Russian — they are bland instead, completely skewing our idea of the heroine. Of the three nineteenth-century versions, then, the first makes Jane other-than-beautiful (rather like the original in this respect), the second somewhat repellent-looking, and the third uninteresting as well as unattractive.

In the twentieth century, the anonymous 1901 translation, abridged for a youth audience, omits most of the rare references to Jane’s looks altogether. She is small, slight, and pale and was no beauty as a child but that is about it. Finally, the two modern translations (Stanevich in 1950, and Gurova in 1999) bring their own nuances to the table. Gurova’s translation is scattered with colloquial and somewhat disparaging epithets such as замухрышка37 (for ‘no beauty’; this term, evocative of Cinderella, could be translated loosely as mousy-looking or drab) and худышка38 (‘scrawny’, for Rochester’s ‘assez mince’).39 This adds a nuance to our perception of Jane: she seems easier to overlook or look down at. Her marked features are here ‘unusual / необычные’; Jane lacks not only even ‘a shade of beauty’ (‘и тени красоты’) but even any prettiness (‘лишена миловидности’).40 Stanevich is kinder to Jane: rather than having nothing to recommend her, she merely regrets that she is ‘not beautiful enough / недостаточно красива’.41 On the whole, her word choices are more restrained and consistent, with a Jane who looks serious, focused, and by no means a beauty — but that may well be her virtue. Overall, the six translations imply six different Janes, the effect of whose appearance on others varies from unpleasant to other than dazzling.

Jane, with Russian Eyes

Perhaps the closest to a literary portrait of the heroine we get in the novel is a scene where, the morning after the proposal scene, Rochester praises Jane’s ‘dimpled cheek and rosy lips’, ‘satin-smooth hazel’ hair and ‘radiant hazel eyes’.42 This is the first reference we get to Jane’s eye and hair colour (though we know she brushes her hair smooth from before). With a highly characteristic ambiguity, however, Brontë undermines that description: the whole point of this welcome sketch is that on that particular morning Jane does not look like her usual self. How much of this liberally bestowed information can then be applied to her normal appearance on days when she is not blissfully happy and observed by an ardent lover? Not much, we learn at once as Jane adds, in an aside: ‘(I had green eyes, reader; but you must excuse the mistake: for him they were new-dyed, I suppose.)’ How much can any description in the novel be trusted if the eye of the keenest of observers — a man in love, supposedly looking straight at Jane’s face at the moment of speaking — is so easily deceived?

Smooth brown hair and green eyes, then. And this is as much as we gather of Jane’s appearance. Elsewhere, any reference to it is either vague and general, or comes from clearly unreliable observers, or both. The only exception is Jane’s height, the one point that is corroborated by several reliable sources. Lloyd, the apothecary, judges her to be eight or nine years of age when she is actually ten and Brocklehurst’s first impression is that ‘her size is small’; in the red room mirror she also sees herself as ‘a strange little figure’.43 As an adult, Bessie estimates that she is a head and shoulders shorter than Eliza and about twice slighter than Georgiana Reed; Rochester, as reported by Adèle, describes her to the little girl as ‘une petite personne, assez mince et un peu pâle’, and Adèle also thinks this a fitting description of her mademoiselle.44 Jane’s paleness is also corroborated by herself,45 so we can safely add it to the slim list of the four or five things we will have gathered about her looks by the end of the novel: small stature, slight figure, a pale face, smooth brown hair, and what she later refers to, once more, as ‘changeable green eyes’.46

The Russian translators vary in how they treat these grains of information we glean to imagine a face and figure to which we could attribute the novel’s 183,858 words. For instance, Rochester’s description quoted above is omitted entirely in the 1901 version. As for the available translations of his description of Jane, only Gurova’s 1990 translation renders each element faithfully (and even she makes Jane’s hair silky ‘шелковистые’ rather than satin-smooth, referring to their texture rather than implying also a hairstyle). Gurova is also the only one to make an attempt at translating ‘sunny-faced’ or mention the dimple on Jane’s cheek, with Stanevich going for ‘rosy / румяные’47 cheeks and the other translators omitting the reference and focusing on the more conventional rosy lips. The notions of Jane as a ‘pale, little elf’ and a ‘sunny-faced girl’ in the same scene baffles the translators as well. Stanevich and Gurova differ in their choice for ‘girl’, which is ambiguous in Russian. Stanevich goes for ‘девушка’48 (young woman) while Gurova chooses ‘девочка’49 (usually, a little girl, making Jane, who is already ‘almost like a child’ in stature, at once a lot more childlike). Their nineteenth-century predecessors forego the elf (Vvedenskii goes for a ‘little friend, pale and doleful / маленькій другъ, блѣдный и печальный’50) but make up for it by then reaching for another mythical creature and translating ‘sunny-faced girl’ as an ‘aerial nymph / воздушная нимфа’ as a way to cover both problematic phrases.

Perhaps most strikingly, any reference to Jane’s eyes is omitted from the exchange in the novel’s first translation (though Vvedenskii does mention their green colour towards the end of the novel). In Koshlakova’s epistolary version, the matter of green eyes is particularly interesting: rather than simply say that are green, Jane reports to her correspondent that Rochester showered her with compliments on her beauty and the radiance of her pretty dark eyes, italicises both ‘beauty’ and ‘dark’ as clearly ludicrous suppositions and refers to her friend’s common sense about her eyes which are ‘as you well know, entirely green’ (‘Осыпав комплиментами и мой веселый вид, и красоту, и блеск моих хорошеньких темныхъ глаз…которые, как вам извѣстно, другъ мой, у меня совершенно зеленые’51).52 In this version alone, then, the green colour of Jane’s eyes becomes a trait both implicitly corroborated by another and evident to an objective observer, which only Rochester is blinded to, by the same emotion that blinds him to her lack of beauty. Unsurprisingly, Jane’s description of the scene also exaggerates the original’s gentle irony at Rochester’s expense.

‘Satin-smooth hazel’ hair is another element worth dwelling on, as a paradigmatic example where the idiomatic arsenal of the Russian language changes the protagonist’s appearance ever so gently. Namely, hazel is simply not used to describe either hair or eyes in Russian, the most idiomatic first choice for hair being ‘chestnut’ (каштановый) and for eyes ‘brown’ (карий, which encompasses a range of hues from hazel to dark brown), and these are the words the Russian translators reach for. While culturally and idiomatically equivalent, both chestnut and brown evoke a slightly different (and darker) hue than the original. It goes without saying that Rochester’s touching notion that Jane’s hair colour matches her eyes goes out of the window together with the word ‘hazel’ in all the translations.

The repercussions of these seemingly slight changes, however, go deeper than we may anticipate. As translation variation goes, they adjust the little we know of Jane’s appearance. In terms of the relationship between appearance and interpretation, however, they also do away with a nuance Brontë was probably aware of from observation (or else why would she have planted the word ‘changeable’ in the second reference to Jane’s eyes, or come up with Rochester’s striking blunder in the first place): namely, that in reality, it is easy to mistake hazel eyes for green, while the opposite is impossible. Hazel eyes have some green in them, as well as brown; the two eye colours share the same pigment, pheomelanin, dominant in the green eye colour and supplemented with another dominant pigment, brownish-black eumelanin, in hazel irises. In other words, rather than going with Jane’s unlikely interpretation that Rochester’s love made her eyes ‘new-dyed’ for him that morning, it is safe to assume that Jane’s ‘changeable green’ eyes are in fact hazel, i.e., light brown with a green tinge to them. In other words, Rochester, not Jane, identifies her eye colour most accurately, although Jane is unaware of the fact and, as we know, is quick to reject the suggestion. The fact that Russian does not distinguish between these colours for eyes makes this ambiguity near-impossible to preserve in translation.

Choosing how to translate ‘hazel’, most people imagine this eye colour as a kind of light brown, and when an exact equivalent is lacking, would lean in that direction as the closest equivalent available, just as the Russian translators did. Yet brown eyes are common, while both hazel and especially green are a rarity. The fact that Jane clearly identifies as being green-eyed is, in other words, a matter not of objective truth, as she — and Koshlakova’s version — make it appear, but of Jane’s self-perception (quite in harmony with the little green men Rochester, too, associates her with independently from her eye colour). In other words, this seemingly minor detail reveals Jane to us as a less than objective narrator. These are the eyes through which we perceive the novel’s entire world, which later become Rochester’s eyes as well: how reliably do they perceive themselves?

As well as making us wonder about the reliability of the many other ‘objective’ pronouncements Jane makes in the novel, Rochester’s alleged mistake provides a unique insight into Jane’s sense of identity. The forgivable and very human bias of identifying entirely with one aspect of her eye colour may be aesthetic, as she is an artist, or reflect her sense of being different, or both. Can it be that, reconciled with what she, and most people around her, perceive as her lack of beauty, she takes comfort in her unusual and striking eyes that she would never acknowledge even to herself? If so, Brontë’s game in terms of the character’s psychologisation may be even subtler and even more modern here (coming from an author writing half a century before Freud) than most critics, including Shuttleworth’s meticulous study of Brontë and Victorian psychology, give her credit for. Unsurprisingly, Charlotte Brontë’s eyes may have been hazel as well, which would explain the inside joke and imply a note of self-irony in Jane’s portrayal (the novel was, after all, billed as an autobiography).53

Invisibly Centre Stage: A Prismatic Approach

Jane Eyre is, in general, notoriously attentive to the processes of both observing and interpreting from observation. We can recall Jane scrutinising Grace Poole or comparing St John’s looks to Rosamond’s to estimate the likelihood of their union. Characters are constantly aware — or, indeed, unaware — of being observed (we recall Jane’s discomfort under Mr Brocklehurst’s ‘two inquisitive-looking grey eyes which twinkled under a pair of bushy brows’54), or learn of having been observed in the past (e.g., when Rochester tells Jane the story of their first encounters from his perspective, or Mrs Reed explains many years later how she perceived the rebellious child in the red room). From physiognomic reading of personality to interpreting emotions, making decisions based on a deliberate reading of appearance is a large aspect of both of the novel’s courtships, perhaps best expressed in a scene where St John, Jane tells us, ‘seemed leisurely to read my face, as if its features and lines were characters on a page’.55 In a sense, this mirrors not only the fake gypsy’s intense focus on Jane’s features (which, again, does nothing to help us imagine them visually) but also Rochester’s proposal, when Jane asks to read his countenance, an ordeal Rochester finds it hard to endure, despite his prediction that she would ‘find it scarcely more legible than a crumpled, scratched page’ (217).56 The peculiar ‘art of surveillance’ that characterises the novel is part and parcel of what Shuttleworth calls ‘Brontë’s challenge to realism’, and compensates for her tendency to narrators ‘devoted as much to concealing as to revealing the self’.57

The way in which characters consistently find an interpretative resource in physical appearance, visible to them but concealed from the reader, keeps us aware that appearances contain the key to interpretation, and that we have no access to it as readers. There is a good reason for that. Very much a precursor to the modernists where sparse character description is concerned, Brontë is аlso an author preoccupied with the power of the imagination: it suffices to recall Jane’s intense inner life, as reflected in her drawings. While regularly emphasising the importance of what we cannot see, she leaves much to the reader’s imagination. A few key features are scattered carefully throughout the text, and the rest is up to us. Lessing points out that, due to the nature of literature, where a portrait has to unfold in time, phrase by phrase, and no unified impression is possible as it is in painting, the only way to approximate such instantaneous impact is to focus on one salient trait and let the reader’s mind do the rest.58 Brontë’s way of handling the inherent differences between literature and reality is to refuse to compensate for the reader’s inability to see the whole picture. Instead, she embraces this limitation by providing a portrait that, far from standing for a visual image, may be as complete, or as approximate, as reliable, or as inaccurate, as suits the author’s design.

In Jane’s case, this principle is elevated to the level of what Yuri Lotman calls a ‘minus-device’, i.e., a marked lack or omission that becomes a literary device in itself.59 A salient example is the well-known episode where Jane sets herself the unforgiving task of drawing her own image and that of her rival (ironically, the latter is at that point based on a verbal description alone). The novelist tantalises the reader with Jane’s drawing of her ‘real head in chalk’ that, unlike her sketch of Rochester, reveals nothing to us: ‘Listen, then, Jane Eyre, to your sentence: to-morrow, place the glass before you, and draw in chalk your own picture, faithfully; without softening one defect: omit no harsh line, smooth away no displeasing irregularity; write under it, “Portrait of a Governess, disconnected, poor, and plain”’.60 We already cannot reach Jane through a literary portrait; similarly, her actual portrait is marked by the defiant absence of any description.

Apart from a few basic facts and a few subjective references, descriptions to Jane’s looks are not only sparse but deliberately apophatic. A chorus of detailed — indeed, minute — epithets lists, from the very first page of the novel, all the things Jane is not. As a child, she is not attractive or sprightly, light, frank, natural, physically strong, sanguine, brilliant, careless, exacting, handsome, romping, nice, or pretty. Betty thinks she was ‘no beauty’ as a child.61 When Jane grows up, she regrets she is ‘not handsomer’ and cannot boast ‘rosy cheeks, a straight nose, and small cherry mouth’, or being ‘tall, stately, and finely developed in figure’; her features are, as we have discussed, not regular and she looks like she is not from this world.62 The only predicates ever applied to Jane that are not apophatic in themselves describe her as difficult to describe or place: she has ‘cover’, appears to be of an unclear age, and so on.63 In the rare instances a positive description does occur, the epithets used, though they imply something about appearance, tend to really refer to personality instead, such as the bounty of four whole adjectives that actually tell us nothing about how Jane looks (‘quaint, quiet, grave, and simple’), or descriptions such as ‘queer, frightened, shy, little thing’, or ‘gentle, gracious, genial stranger’.64

How does a ‘minus-device’ fare in translation? Not too well, as it turns out. On the one hand, seemingly minor choices gain in significance as a result, leading to larger shifts in emphasis. On the other, different translators’ strategies tend to be consistent despite variation in the translation choices, which suggests that the translators’ reading of the text is affected by Brontë’s apophatic portrayal of her heroine. One such strategy is to make anything resembling appearance more salient; for instance, where Jane imagines that she may have been a ‘sanguine, brilliant, careless, exacting, handsome, romping child’, good looks are only mentioned in passing; yet they are emphasised in every single Russian translation of this description.65 Another is to avoid any suggestion of appearance altogether. The four Russian translations that feature the quotation involving the ‘gentle, gracious, genial stranger’, for example, choose adjectives that refer clearly to Jane’s personal qualities rather than (as the English ‘gentle’ and ‘gracious’ suggest) at least tangentially to the outward impression she may make. In Russian, Jane becomes, in the earliest translation, noble and magnanimous / ‘великодушную и благородную особу’,66 then turns into a ‘sweet, nice, loving creature / милое, симпатичное, любящее существо’67 in the 1893 version, and finally a ‘meek, elevated and merciful soul / кроткой, возвышенной, милосердной души’68 in 1990.69

In the context of a minus-device, connotations also gain in importance. The translator cannot avoid interpretation, and often already suggestive adjectives lead us to divergent impressions in Russian. Rochester’s comparison of Jane to a ‘nonnette’ is one case in point.70 Vvedenskii’s (1849) very free translation goes with ‘институтка’71 (an institute girl). This is an interesting choice in itself: though Lowood is an ‘institution’ rather than an ‘institute’, the word may seem like a potentially felicitous solution given Jane’s background. Yet the Russian analogue conjures up a very different image: that of a young graduate of the Smolny Institute for aristocratic young ladies. The cultural connotations this evokes are hardly nun-like or Quakerish, and would suggest, in 1849, a well-bred and sheltered young lady from an excellent family. Interestingly, just a year before Vvedenskii’s translation came out, Smolny Institute had opened a two-year class to train female teachers, which may or may not have influenced this translator’s choice.

Unsurprisingly, once the notion of a Smolny girl is introduced, Vvedenskii then cannot convincingly translate the other adjectives in the passage (‘quaint, quiet, grave, and simple’) and makes them refer to Jane’s ‘composed, serious and somewhat naive pose / спокойной, серьёзной и нѣсколько наивной позѣ’.72 Koshlakova (1857), who translated from Old Nick’s adaptation, follows the French to turn Jane into more of a nun: ‘priggish, composed, serious, simple, with constantly folded hands / напыщенную, спокойную, серьезную, простую, съ вѣчно сложенными руками’73 (in English, Jane only looks like a nun in that moment, with folded arms, not constantly). Stanevich, a century later, makes her ‘quiet, grave, calm / тихая, строгая, спокойная’,74 and Gurova, in 1990, ‘old-fashioned, quiet, grave, naive/unsophisticated / старомодная, тихая, серьезная, бесхитростная.’75 The range of the images projected is telling: from Vvedenskii’s sophisticated young lady via the rather Eliza-like imposing figure of a nun, and finally to Gurova’s old-fashioned simpleton.

In certain paradigmatic cases, prismatic variation in emphasis is amplified by linguistic variation. Consider the moment where Rochester admits to his inability to guess Jane’s age, a precious clue as to her looks: Jane’s ‘features and countenance are so much at variance’, he explains.76 But what does this mean? Quite apart from the cryptic nature of the remark itself, Russian is hard put to trace the distinction between features and countenance. While technical analogues may be found, they are inexact and, when not juxtaposed, the two words are likely to be translated in the same way. So, while a couple of the translations go down the cryptic route (e.g., ‘features’ vs ‘expression’), two attempt interpretation: the very first translation of the novel into Russian, by Vvedenskii, juxtaposes Jane’s figure (her body silhouette) with her ‘physiognomy / физіономіею’,77 while the canonical Stanevich translation decodes the enigma in its own way: ‘childlike appearance and seriousness / детский облик и серьезность’.78 Thus, dealing with the ambiguity of Jane’s looks in the novel leads, in one case, to a reference to Jane’s body, exceptional in the novel, and in the other — to her making a childlike impression.

Prismatic variation in translation is already striking when it comes to a key trope as dependent on a handful of carefully chosen words as character description. The effect is further amplified in Jane’s case, given how little of her appearance we can pin down. The Russian translations of Rochester’s remark ‘you have rather the look of another world. I marvelled where you had got that sort of face’79 are another example of the extent to which cross-lingual difference can direct the translator’s hand in such an ambivalent setting. Russian has two words for ‘world’, one (‘мир’) homonymous with the word for peace and the other (‘свет’) with that for light. The latter has strong connotations of the afterlife, and that is the word used by both Vladimirov and the anonymous 1901 translator. Accordingly, all the pre-1950 translations lean towards the look not so much of ‘another’ as ‘the other’ world, making Jane not so much a fairy as something of a revenant. The modern two translations diverge: Stanevich goes for ‘you look like a creature from another world / вы похожи на существо из другого мира’80 (a stronger image than merely having the look of another world) and Gurova for ‘there is something about you that is not from this world / в вас сквозит что-то не от этого мира.’81 Here, the overall effect of the minus-device pushes the translators to make Jane even more of an otherworldly being than she already is in English, and a good deal more sinister.

To conclude, it seems clear that variation in translation goes beyond descriptive nuances and affects the novel’s deepest structures, such as the visual representation of a character and, by extension, that character’s relationships and motivations. For instance, the same story reads differently with a repellent-looking Jane as opposed to one that is perhaps underappreciated but rather pretty. In certain cases, as with ‘hazel’ for Jane’s eye colour, the translation affects not only her appearance but also, potentially, the way we think of her looks (standard or exotic) and how Jane comes across as a narrator (objective or biased). There is only so much we can do to trace the exact image that each version of a text produces for each reader. Yet an analysis of the prompts that such an image is based on lifts the veil on prismatic variation that goes beyond a given translation or language: as well as a multiplicity of books, Jane Eyre’s many translations create a multiplicity of imagined persons across the globe.

Paradoxically, with an underdescribed character such as Jane, the effect can be even stronger, as evident from one compelling testimony. A Russian summary of the novel, published in 1850, muses on Jane’s appearance as follows: ‘Jane Eyre was no beauty, not even pretty. But her characteristic facial features cannot be imagined in any way other than as the imprint of great resources of the soul: a firm, unshakeable will and a readiness for an anything but lustreless fight with destitution and grief.’82 The author of this review bases their summary on Vvedenskii’s translation, which they cite extensively word for word, and has evidently derived from it a clear notion of Jane’s features and of the importance of that strong mental image for characterisation. The character’s actions successfully fill in the gaps in Jane’s portrait, resulting in a convincing image — an image based on mere crumbs of description Brontë scatters for her readers and now refracted through the prism of another language — which the contemporary Russian critic confidently declares the only one imaginable. The image itself, however, is transient, and succeeded, with new translations, by mental representations where Jane comes across as now plain, now priggish, now pretty, or otherworldly: forever a changeling, fairy-born and human-bred.

Works Cited

Russian Translations of Jane Eyre (in chronological order)

List researched and compiled by Eugenia Kelbert and Karolina Gurevich

April 1849, summary with translated excerpts:

“Literaturnye Novosti v Anglii: Dzhenni Ir: Avtobiografiia,” Biblioteka dlia chteniia, 1849, Vol. 94/2, Seg. 7, pp 151–72.83

May 1849, first translation by Irinarkh Vvedenskii (divided in 5 parts):

Irinarkh Vvedenskii, “Dzhenni Ir. Roman,” Otechestvennye zapiski, 1849, Vol. 64/6, Seg. 1, pp 175–250; Vol. 65/7, Seg. 1, pp. 67–158; Vol. 65/8, pp 179–262; Vol. 66/9, Seg. 1, pp 65–132, Vol. 66/10, Seg. 1, pp 193–330. Extracts from this translation were included in “Dzhen Eĭr, roman Korrer Bellia.” Sovremennik. St Petersburg, 1850. Vol. 21/6, Seg. 4, pp 31–38.

1857, translation by S. I. Koshlakova, abridged and recast as an epistolary novel (three parts). Translated from the French adaptation Jane Eyre. Mémoires d’une gouvernante, Imité par Old Nick (Paris: Hachette, 1855):

Bronte Sh. Dzhenni Eĭr, ili Zapiski guvernantki, trans. S. I. K…voĭ, Biblioteka dlia dach, parokhodov i zheleznykh dorog, St. Petersburg: Tipografiia imperatorskoĭ akademii nauk, 1857.

Translation of the German play adaptation by Charlotte Birch-Pfeiffer, Die Waise aus Lowood (1853):

Charlotte Birch-Pfeiffer, Lovudskaya sirota: Zhan Eyre, trans. by D. A. Mansfeld, Moscow: Litographia Moscowskoy teatralnoy biblioteki E. N. Rassohinoy, 1889.

1893, translation by V.D. Vladimirov:84

Bronte Sh. Dzhenni Eĭr (Lokvudskaia Sirota). Roman-avtobiografiia v 2kh chastiakh. Trans. V. D. Vladimirov, St Petersburg: M.M. Lederle & Ko, 1893.

1901, anonymous translation, abridged for a youth audience:

“Dzheni Eĭr, istoriia moeĭ zhizni,” Sharloty Bronte. Sokraschennyĭ perevod s angliĭskogo. IUnyĭ chitatel’, zhurnal dlia deteĭ starshego vozrasta, Vol. 3, 5, St Petersburg, 1901

1950, canonical Soviet translation by Vera Oskarovna Stanevich:

Bronte, Sharlotta. Dzhen Eĭr, Trans. V. Stanevich, Moscow: Goslitizdat (Leningrad: 2ia fabrika det. Knigi Detgiza), 1950

1990, Vera Stanevich’s translation with censored passages restored by Irina Gurova:

Bronte, Sharlotta. Dzhen Eĭr, Trans. V. Stanevich (omissions in the texts reconstructed by I. Gurova), Moscow: Khudozhestvennaia literatura, 1990

1999, translation by Irina Gurova:

Bronte, Sharlotta. Dzheĭn Ėĭr, trans. I. Gurova and Rozhdestvo v Indii by Barbara Ford, trans. V. Semenov. Moscow: AST, 1999

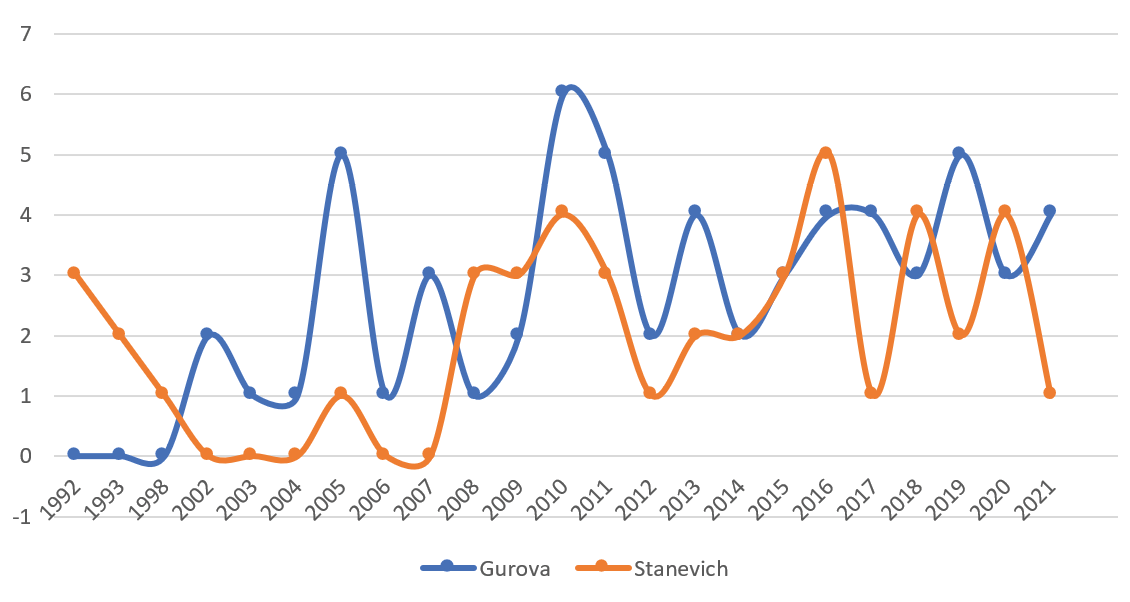

The Gurova and Stanevich translations have both been much reprinted: Figure 23 shows their relative popularity.

Fig. 23 Reprints and re-editions of the Gurova and Stanevich translations, researched and created by Karolina Gurevich

Other Sources

Andrew, Dudley, ‘The Well-Worn Muse: Adaptation in Film History and Theory’, in Narrative Strategies: Original Essays in Film and Prose Fiction, ed. by Syndy M. Conger and Janet R. Welsh (Macomb: Western Illinois UP, 1980), pp. 9–19.

Berman, Antoine, ‘La Traduction comme épreuve de l’étranger’, Texte, 4 (1985), 67–81.

——, ‘Translation and the Trials of the Foreign’, trans. Lawrence Venuti, in The Translation Studies Reader, ed. by Lawrence Venuti (London: Routledge, 2000), pp. 240–53.

Boshears, Rhonda and Harry Whitaker, ‘Phrenology and Physiognomy in Victorian Literature’, in Literature, Neurology, and Neuroscience: Historical and Literary Connections, ed. by Anne Stiles, Stanley Finger, and François Boller (Amsterdam: Elsevier, 2013), https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-444-63273-9.00006-X

Brontë, Charlotte, Jane Eyre: An Authoritative Text, Contexts, Criticism, 3rd edn, ed. by Richard J. Dunn (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2001).

Demidova, O. R., ‘The Reception of Charlotte Brontë’s Work in Nineteenth-Century Russia’, The Modern Language Review, 89 (1994), 689–96.

Fahnestock, Jeanne, ‘The Heroine of Irregular Features: Physiognomy and Conventions of Heroine Description’, Victorian Studies, 24 (1981), 325–50.

Fan, Yiying and Jia Miao, ‘Shifts of Appraisal Meaning and Character Depiction Effect in Translation: A Case Study of the English Translation of Mai Jia’s In the Dark’, Studies in Literature and Language, 20 (2020), 55–61, http://dx.doi.org/10.3968/11484

Gaskell, Elizabeth, The Life of Charlotte Brontë (Smith, Elder, and Co., 1906), https://www.gutenberg.org/files/1827/1827-h/1827-h.htm

Graham, John, ‘Character Description and Meaning in the Romantic Novel’, Studies in Romanticism, 5 (1966), 208–18.

Hartley, Lucy, Physiognomy and the Meaning of Expression in Nineteenth-Century Culture (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005).

Heier, E., ‘“The Literary Portrait” as a Device of Characterization’, Neophilologus, 60 (1976), 321–33.

Hollington, Michael, ‘Physiognomy in Hard Times, Dickens Quarterly, 9 (1992), 58–66.

Iamalova, Iuliia, ‘Istoriia perevodov romana Sharlotty Brontë “Dzheĭn Eĭr” v Rossii’, Vestnik Tomskovo gosudarstvennogo universiteta, 363 (2012), 38–41.

Jadwin, Lisa, ‘“Caricatured, Not Faithfully Rendered”: Bleak House as a Revision of Jane Eyre’, Modern Language Studies, 26 (1996), 111–33.

Jack, Ian ‘Physiognomy, phrenology and characterisation in the novels of Charlotte Brontë’, Brontë Society Transactions, 15 (1970), 377–91.

Kelbert, Eugenia, ‘Appearances: Character Description as a Network of Signification in Russian Translations of Jane Eyre’, Target: International Journal of Translation Studies, 34.2 (2021), 219–50, https://doi.org/10.1075/target.20079.kel

Klinger, Suzanne ‘Translating the Narrator’, in Literary Translation, ed. by J. Boase-Beier, A. Fawcett, and P. Wilson (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2014), pp. 168–81.

Levin, Yu. D., Russkie perevodchiki XIX veka i razvitie khudozhestvennogo perevoda (Leningrad: Nauka, 1985).

Lotman, Yuri, The Structure of the Artistic Text, trans. by Gail Lenhoff and Ronald Vroon (Ann Arbor: Dept. of Slavic Languages and Literature, University of Michigan, 1977).

Macdonald, Frederika, The Secret of Charlotte Brontë (London: T. C. & E. C. Jack, 1914), https://www.gutenberg.org/files/41105/41105-h/41105-h.htm.

Orel, H. [John Stores Smith], ‘Personal Reminiscences: A Day with Charlotte Brontë’, in The Brontës. Interviews and Recollections, ed. by H. Orel (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 1997).

Pearl, Sharrona, About Faces: Physiognomy in Nineteenth-Century Britain (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2010).

Reynolds, Matthew, ed., Prismatic Translation (Cambridge: Legenda, 2020).

Sarana, Natal’a V., ‘Traditsiia angliĭskogo romana vospitaniia v russkoĭ proze 1840–1870h godov’ (unpublished doctoral thesis, National Research University Higher School of Economics, 2018).

Shuttleworth, Sally, Charlotte Brontë and Victorian Psychology (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996).

Syskina, Anna, ‘Perevody XIX veka romana “Dzhen Eĭr” Sharlotty Brontë: peredacha kharaktera i vzgliadov geroini v perevode 1849 goda Irinarkha Vvedenskogo’, Vestnik Tomskogo gosudarstvennogo pedagogicheskogo universiteta, 3 (2012), 177–82.

——, ‘Russian Translations of the Novels of Charlotte Brontë in the Nineteenth Century’, Brontë Studies, 37 (2012), 44–48.

Syskina, Anna A. and Vitaly S. Kiselev, ‘The Problem of Rendering Psychological Content in V. Vladimirov’s Translation of Jane Eyre (1893)’, Brontë Studies, 40 (2015), 181–86.

Thackeray Ritchie, Anne. Letters of Anne Thackeray Ritchie, with Forty-two Additional Letters from her Father William Makepeace Thackeray, ed. by Hester Ritchie (London: John Murray, 1924).

Vvedenskii, Irinarkh, ‘O perevodakh romana Tekkereia “Vanity Fair” v “Otechestvennykh’’ Zapiskakh” i “Sovremennike”’ Otechestvennye zapiski, 1851, Vol. 78, № 9/8, pp. 61–81 (p. 75).

Walker, Alexander. Physiognomy founded on Physiology (London: Smith, Elder, and Co., 1834), https://archive.org/details/physiognomyfound00walk/page/14

Wells, Samuel R., New Physiognomy; or, Signs of Character, as manifested through Temperament and External Forms, and especially in “The Human Face Divine” (London: L. N. Fowler & Co., 1866).

Zunshine, Lisa, Why We Read Fiction: Theory of Mind and the Novel (Columbus, OH: Ohio State University Press, 2006.

1 For a detailed analysis of the Russian translations of appearance in Jane Eyre that complements this article, see ‘Appearances: Character Description as a Network of Signification in Russian Translations of Jane Eyre’, Target: International Journal of Translation Studies, 34.2 (2021), 219–50. This research was supported by a Leverhulme Early Career Fellowship. I would also like to acknowledge the contribution of Aruna Nair and three research assistants: Karolina Gurevich, Alesya Volkova, and Olga Nechaeva.

2 Dudley Andrew, ‘The Well-Worn Muse: Adaptation in Film History and Theory’, in Narrative Strategies: Original Essays in Film and Prose Fiction, ed. by Syndy M. Conger and Janet R. Welsh (Macomb: Western Illinois University Press, 1980), pp. 9–19 (pp. 12–13).

3 E. Heier, ‘“The Literary Portrait” as a Device of Characterization’, Neophilologus, 60 (1976), 321–33 (p. 323).

4 Heier, ‘“The Literary Portrait”’, p. 323.

5 Ibid., p. 323.

6 See Lisa Zunshine, Why We Read Fiction: Theory of Mind and the Novel (Columbus, OH: Ohio State University Press, 2006).

7 Lisa Jadwin, ‘“Caricatured, Not Faithfully Rendered”: Bleak House as a Revision of Jane Eyre’, Modern Language Studies, 26 (1996), 111–33 (p. 112).

8 This makes for a particularly revealing case study of the literary portrait as a network of signification in translation, as argued in Kelbert, ‘Appearances’. (See also Antoine Berman, ‘La Traduction comme épreuve de l’étranger’, Texte, 4 (1985), 67–81; and ‘Translation and the Trials of the Foreign’, trans. by Lawrence Venuti, in The Translation Studies Reader, ed. by Lawrence Venuti (London: Routledge, 2000), pp. 240–53). Cf. Yiying Fan and Jia Miao, ‘Shifts of Appraisal Meaning and Character Depiction Effect in Translation: A Case Study of the English Translation of Mai Jia’s In the Dark’, Studies in Literature and Language, 20 (2020), 55–61 for further examples of character description variation in translation.

9 JE, Ch. 21.

10 JE, Ch. 36.

11 See Kelbert, ‘Appearances’, for a more detailed discussion of physiognomy in Jane Eyre. To quote Sally Shuttleworth, ‘[i]n many places, where the study of human character from the face became an epidemic, the people went masked through the streets’ (Sally Shuttleworth, Charlotte Brontë and Victorian Psychology (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996), p. 56). See Alexander Walker, Physiognomy founded on Physiology (London: Smith, Elder and Co., 1834), and Samuel R. Wells, New Physiognomy; or, Signs of Character (London: L. N. Fowler & Co., 1866) for contemporary accounts. For further background on the uses of physiognomy in Victorian literature, see Rhonda Boshears and Harry Whitaker, ‘Phrenology and Physiognomy in Victorian Literature’, in Literature, Neurology, and Neuroscience: Historical and Literary Connections, ed. by Anne Stiles, Stanley Finger, and François Boller (Amsterdam: Elsevier, 2013), pp. 87–112; Lucy Hartley, Physiognomy and the Meaning of Expression in Nineteenth-Century Culture (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005); Michael Hollington, ‘Physiognomy in Hard Times’, Dickens Quarterly, 9 (1992), 58–66; Ian Jack, ‘Physiognomy, phrenology and characterisation in the novels of Charlotte Brontë’, Brontë Society Transactions, 15 (1970), 377–91; John Graham, ‘Character Description and Meaning in the Romantic Novel’, Studies in Romanticism, 5 (1966), 208–18; and Sharrona Pearl, About Faces: Physiognomy in Nineteenth-Century Britain (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2010).

12 JE, Ch. 37.

13 Kelbert, ‘Appearances’.

14 See Anna Syskina, ‘Perevody XIX veka romana “Dzhen Eĭr” Sharlotty Brontë: peredacha kharaktera i vzgliadov geroini v perevode 1849 goda Irinarkha Vvedenskogo’, Vestnik Tomskogo gosudarstvennogo politekhnicheskogo universiteta, 3 (2012), 177–82.

15 Vvedenskii, Irinarkh, ‘O perevodah romana Tekkereia “Vanity Fair” v “Otechestvennykh’’ Zapiskakh” I “Sovremennike”’ Otechestvennye zapiski, 1851, Vol. 78, № 9/8, 61–81 (p. 75). For more about the context of this polemic and on Vvedenskii’s method, see also Levin, Yu. D., Russkie perevodchiki XIX veka i razvitie khudozhestvennogo perevoda (Leningrad: Nauka, 1985), 124–36.

16 I thank Ekaterina Samorodnitskaya for pointing me to Vvedenskii’s remarks. Charlotte Brontë’s identity became known in 1848, but it does not seem that the information had reached Russia by 1849 when Vvedenskii’s translation came out in five instalments of Otechestvennye zapiski throughout the year. Notably, the summary of the novel published in the same year in another journal Vvedenskii contributed to regularly, Biblioteka dlia chteniia, still speculates on whether the author is male or female. Vvedenskii’s bitter words published in 1851, then, come across as an afterthought rather than an actual description of his motivation for the extensive changes he made. While he may have been less keen to go to great pains to convey the spirit (his alleged goal as a translator) of some ‘English governess’, his treatment of Jane Eyre is not that different from that of Thackeray or Dickens. In fact, in the same essay, Vvedenskii argues about Thackeray that the translator will ‘inevitably and certainly destroy the particular colour of this writer if he translates him <…> too closely to the original, sentence by sentence.’ (‘неизбѣжно и непрeмѣнно уничтожитъ колоритъ этого писателя, если станетъ переводить его <…> слишкомъ-близко къ оригиналу, изъ предложенiя въ предложенiе’ italics in the original, ibid, p. 69). Vvedenskii’s wording leaves it ambiguous if his alleged disrespect was to do with the qualities of Jane Eyre or merely with the author’s identity; his jabs both at Brontë and at his fellow translators who, he points out, treat the ‘English governess’ author just as poorly suggest, however, that his stepping forward to take credit as the Russian novel’s co-creator was related to the discovery of the person behind the pseudonym.

17 See Chapters I & II above for a discussion of this version and its translation into other languages.

18 See Chapter I above.

19 Anna Syskina, ‘Russian Translations of the Novels of Charlotte Brontë in the Nineteenth Century’, Brontë Studies, 37 (2012), 44–48 (p. 45).

20 Stanevich may have gained the Soviet establishment’s official seal of approval, but she was, as a translator, anything but a product of the Soviet system. A symbolist poet and founder of a literary salon, she was an active member of pre-revolutionary literary circles, and her language expertise and stylistic intuition were formed within a world that disappeared in 1917.

21 Vvedenskii’s and Vladimirov’s translations, like Stanevich’s, cut out the novel’s final passage about St John’s letter, betraying a curious agreement between the Soviet censor’s anti-religious feeling and, presumably, the aesthetic sense of the nineteenth-century translators.

22 Iuliia Iamalova (3) claims that Gurova’s translation was published the same year, i.e., in 1990 (see ‘Istoriia perevodov romana Sharlotty Brontë “Dzheĭn Eĭr” v Rossii’, Vestnik Tomskovo gosudarstvennogo universiteta, 363 (2012), 38–41, p. 40). It seems, however, that the first edition of Gurova’s translation came out in 1999, under the same cover as a novel by Barbara Ford. I thank Alexey Kopeikin for his advice that helped locate this edition.

23 Jeanne Fahnestock, ‘The Heroine of Irregular Features: Physiognomy and Conventions of Heroine Description’, Victorian Studies, 24 (1981), 325–50 (p. 333).

24 Ibid., p. 329.

25 Elizabeth Gaskell, The Life of Charlotte Brontë (London: Smith, Elder, and Co., 1906), n.p. https://www.gutenberg.org/files/1827/1827-h/1827-h.htm

26 JE, Ch. 34.

27 JE, Ch. 11.

28 JE, Chs 3, 29, and 24.

29 A Russian 1850 resumé of the novel adds another, much earlier compliment, translating Rochester’s ‘you are no more pretty than I am handsome, yet a puzzled air becomes you’ as ‘You are far from being a beauty, just as I am not a handsome man; but at this moment you are rather pretty’ (‘Вы далеко не красавица, также какъ и я не красивый мужчина; но въ эту минуту вы довольно-миловидны’). ‘Dzhen Eĭr, roman Korrer Bellia’, Sovremennik. St Petersburg, 1850. Vol. 21/6, Seg. 4, pp. 31–38 (p. 32).

30 JE, Ch. 16.

31 Vvedenskii, p. 132.

32 Koshlakova, p. 21.

33 JE, Ch. 14.

34 Koshlakova, p. 128.

35 Vladimirov, p. 567.

36 JE, Ch. 11.

37 Gurova, p. 51.

38 Ibid. p. 66.

39 JE, Ch. 13.

40 Gurova, p. 55.

41 Stanevich, p. 104.

42 JE, Ch. 24.

43 JE, Chs 4 and 2.

44 JE, Ch. 13.

45 JE, Ch. 11.

46 JE, Ch. 34.

47 Stanevich, p. 104.

48 Ibid. p. 249.

49 Gurova, p. 145.

50 Vvedenskii p. 66.

51 Koshlakova, p. 74.

52 In this, Koshlakova translates accurately from ‘Old Nick’’s French: ‘Lorsqu’il m’eut félicitée sur ma bonne mine, sur ma beauté même, et sur l’éclat de mes jolis yeux bruns, — ils sont verts, comme vous le savez, ma chere [sic] amie…’ (Jane Eyre, tr. Old Nick, 1855, p. 86)

53 Brontë was, like Jane, of very short stature and had notoriously irregular features; Ann Thackeray Ritchie notes ‘a general impression of chin about her face,’ (Letters of Anne Thackeray Ritchie, ed. by Hester Ritchie (London: John Murray, 1924), pp. 269–70), and Elizabeth Gaskell a ‘crooked mouth’ and a ‘large nose’. The latter describes her eyes as follows: ‘They were large, and well shaped; their colour a reddish brown; but if the iris was closely examined, it appeared to be composed of a great variety of tints’ (Gaskell, The Life of Charlotte Brontë, Ch. 6, n.p.). Elsewhere, Gaskell makes the same apparent mistake as Rochester: having mentioned her ‘soft brown hair’, she then describes Brontë’s eyes as ‘(very good and expressive, looking straight and open at you) of the same colour as her hair’ (The Life of Charlotte Brontë, Ch. 7). Even though others, notably Matthew Arnold and Gaskell’s daughter, refer to Brontë’s eyes as grey, the very confusion in Gaskell’s description seems to suggest eyes that were, like Jane’s, multi-coloured with a predominance of brown, supplemented with green, grey, or a variety of tints: in other words, hazel. Indeed, another visitor once referred to them as ‘chameleon-like, a blending of various brown and olive tints’ (The Brontës: Interviews and Recollections, ed. by H. Orel (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 1997), p. 166). Brontë’s drawing entitled ‘Study of eyes’ provides an eloquent, if black-and-white, testimonial of her fascination with eyes and their structure (reprinted in Shuttleworth, Charlotte Brontë, n.p.).

54 JE, Ch. 4.

55 JE, Ch. 30.

56 JE, Ch. 23.

57 Shuttleworth, Charlotte Brontë, p. 17.

58 Cited in Heier, ‘“The Literary Portrait”’, p. 327.

59 Yuri, Lotman, The Structure of the Artistic Text, trans. by Gail Lenhoff and Ronald Vroon (Ann Arbor: Dept. of Slavic Languages and Literature, University of Michigan, 1977), p. 51.

60 JE, Ch. 16.

61 JE, Ch. 10.

62 JE, Chs 11 and 13.

63 JE, Chs 2 and 13.

64 JE, Chs 14, 4, and 20.

65 JE, Ch. 2.

66 Vvedenskii, p. 220.

67 Vladimirov, p. 266.

68 Gurova, p. 123.

69 A similar transformation occurs with the list of adjectives describing the qualities Jane lacked as a child. Russian translations make them more about Jane’s kindness: evil, bad, cunning, not kind, not tender etc. Yet, Brontë’s carefully selected adjectives tend to imply appearance.

70 JE, Ch. 14.

71 Vvedenskii, p. 98.

72 Ibid. p. 105.

73 Koshlakova, p. 124.

74 Stanevich, p. 134.

75 Gurova, p. 74.

76 JE, Ch. 13.

77 Vvedenskii, p. 123.

78 Stanevich, p. 127.

79 JE, Ch. 13.

80 Stanevich, p. 126.

81 Gurova, p. 68.

82 ‘Дженъ Эйръ не была красавицей, не была даже хорошенькой. Но характерныя черты лица ея нельзя вообразить иначе, какъ съ отпечаткомъ великихъ силъ душевныхъ: воли твердой, непреклонной, и готовности на небезславную борьбу съ нуждой и горемъ.’ (Sovremennik, p. 32).

83 Other published summaries included, notably, Sovremennik (1850, Vol. 21/6, Seg. 4, pp 31–38), a second summary in Biblioteka dlia chteniia (1852, 116: 23–54) and a brief summary in Mir Bozhii (1893, 9: 162–65).

84 Vladimirov’s real name was Vladimir Dmitrievich Vol’fson.