The Time Map https://digitalkoine.github.io/translations_timemap Created by Giovanni Pietro Vitali and Simone Landucci;© OpenStreetMap contributors, © Mapbox

The World Map https://digitalkoine.github.io/je_prismatic_map Created by Giovanni Pietro Vitali; maps © Thunderforest,data © OpenStreetMap contributors

2. Who Cares What Shape the Red Room is? Or, On the Perfectibility of the Source Text

© 2023 Paola Gaudio, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0319.05

Marks

In 2003, when I was studying for my Master’s degree in Literary Translation at the University of East Anglia, I wrote a paper for my Case Studies class. It revolved around the translation of the red room episode in Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre and, among other things, it pointed out a discrepancy between the description of the room in the original version as a ‘spare chamber’, and its Italian translation as a square one by Giuliana Pozzo Galeazzi (1951) and Ugo Dèttore (1974). I was quite confident the professor would appreciate my discovery and reward my effort with high marks, so I was appalled when I found out my essay only got a score of 65% — the lowest in my career as a postgraduate student — possibly my lowest ever. I was even more appalled by the reason for such a low score: the professor claimed it was indeed a square chamber, not a spare one — therefore the translations were perfectly in line with the source text and my essay was inaccurate, based as it was on my assumed negligence.

I could not believe my eyes as I was reading the professor’s comments on my paper, so I went over my English edition again, and I was elated to find out that it did read spare — the mistake was not mine, it was in the translations — and the professor was wrong. I reckoned I had grounds for appeal, and that is exactly what I did, this time attaching a photocopy from my 1966 Penguin edition in order to prove beyond any reasonable doubt that there was nothing wrong with my thesis, and that the red room was actually spare, not square. To cut a long story short, although (or maybe precisely because) I became quite insistent about it, my score was lowered even more. Luckily, this did not prevent me from graduating with distinction, given the high scores I was awarded in all the other classes, but still it left a sour taste. When, more recently, I happened to analyse some of the new translations (Lamberti 2008, Capatti 2013, Sacchini 2014) which, in the meantime, had been published in Italian, it was with great surprise that I noticed the red room was square — yet again.

I know now that not only the score I received twenty-ish years ago was indeed unfair, but what I had stumbled upon was not a simple mistake on the part of a couple of translators: it was a pattern — a pattern which has been perpetuating itself over many decades — at least from the 1951 translation by Pozzo Galeazzi, up until the 2014 one by Sacchini. At this point, it seemed important to trace the origin of these variations, so I investigated them further, and here are my findings.

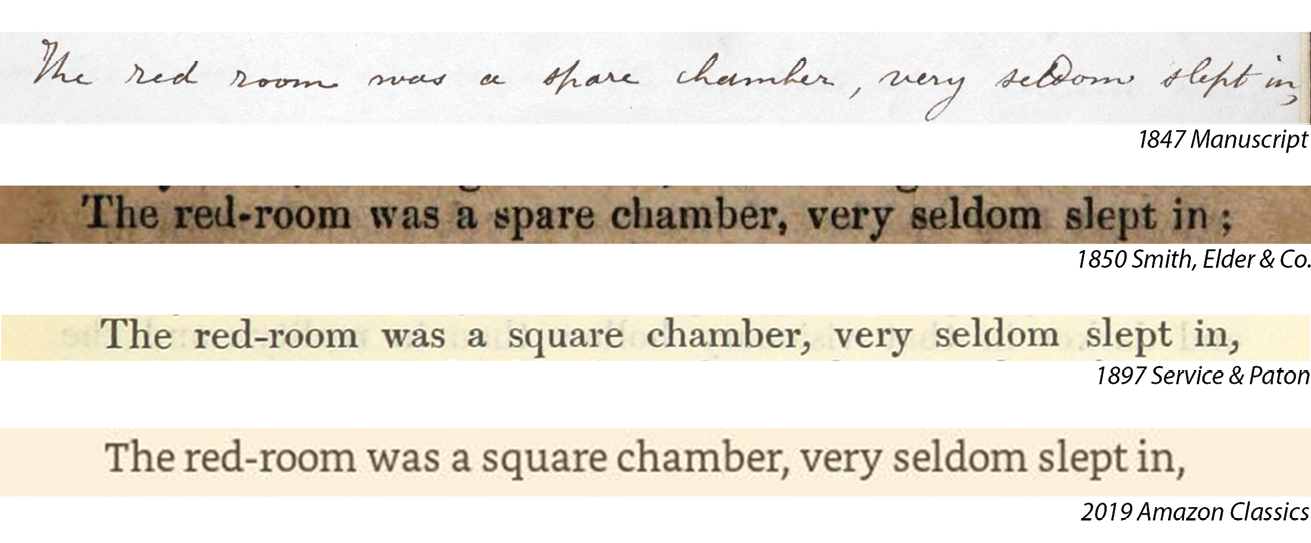

‘The red room was a spare chamber’: this is what Charlotte Brontë actually hand-wrote in 1847, i.e., in the manuscript currently held at the British Library, and on which the first editions are based. The first four editions all faithfully read spare as well. In the 1897 Service & Paton edition, however, spare becomes square. That this mutation in the source text may also have occurred in other print editions cannot be ruled out,1 but what makes the 1897 edition so special is that it was used as a basis for the digitized edition that can most easily be found online, published by Project Gutenberg back in 1998 — at the dawn of the digital revolution.

Because of the vast popularity of Project Gutenberg, it is no surprise that this edition has spread exponentially,2 not only among the reading public but also among publishers who, in the digitized version, can find a handy source for new e-book editions. It is not far-fetched to assume that translators, who by now work exclusively at computers, might have been using the digitized 1897 edition. This would explain why the error is being perpetuated more and more, both in the original English electronic versions (for example the Amazon Classics e-book, which is clearly based on the Project Gutenberg file) and in their translations. The same error would be found in any English printed book based either on the 1897 edition or its digitized version. The truth is that, in the now long-gone era of mechanical reproduction, this mutation would have concerned only prints and reprints of that edition or of those based on it: it would certainly have spread, but its scope would still have been limited. Not so in the digital world, where the power of a digital item — a file freely distributed on the Internet — becomes stronger than any book-as-object, defined as the latter is by its insurmountable yet finite physicality.

Fig. 1 A spare chamber. Images of the manuscript (London, British Library, MS 43474, vol. I, fol. 12r), the 1850 edition (London: Smith, Elder & Co., p. 7) and the 1897 edition (London: Service & Paton, p. 7) are courtesy of the © British Library Board. The 1850 edition was digitised by the Google Books project.

Square replaces spare in many translations, and not only Italian ones, since it is likely that the same mistake can and will be found in other languages as well, as is the case with Luise Hemmer Pihl’s 2016 Danish translation.3 If this is so, it is only because square is what both digitizers and translators have found in their source text: the optical character recognition process is not to blame in this case, but the source text of choice is not the one which best reproduces Charlotte Brontë’s masterly depiction of this uncanny red room. In an era when the distinction between original and reproduction seems to be dead and buried, the digitized version appears to (yet should not) be more authoritative than the original because of its greater availability, and because sometimes virtual reality tends to be more real than reality itself. In this case, the digitized version has become the original text for quite a few readers and translators. Be that as it may, in this widely available digitized file based on the 1897 edition, crucial information about the function of the room (it was spare, therefore seldom used, therefore haunted — as little Jane would soon find out) is replaced by an uninformative, even obvious, detail about its shape: after all, most rooms are quadrangles, either square or rectangular, with fewer cases of oval or circular rooms, and even fewer other shapes — but who would really care?

Because the squareness of the room has become so prominent over the years — not only to me but in the translations as well — I could not help inquiring even further into the matter. I asked the following questions: is the occurrence of the words spare and square of any significance in the rest of the novel? Are there other imprecisions in the 1897 edition? Are there variations in other authoritative English editions, such as the Penguin one? If the optical character recognition (OCR) process did not cause the mutation from spare to square, did it create others? Is it possible to identify errors that are common to most editions? Can patterns of textual variation provide insights into the translations? The quick answer to all these questions is ‘yes’. In what follows, I show why.

Spare and Square

First, it should be made clear that the red-room instance is the only substitution of spare by square that I have discovered: the error is therefore not systematic within any edition of the novel itself. As an adjective, spare is used only three times in Jane Eyre: once it refers to cash (‘some of that spare cash’, Chapter 24), which is a common collocation; the other two concern the description of rooms, such a collocation being similarly very common. The first room, of course, is the red chamber at Gateshead, whereas the other is ‘a spare parlour and bedroom’ at Moor House (Chapter 34), which Jane refurbished as she was expecting her cousins’ return for the Christmas season. However, if the use of spare is straightforward and unproblematic in both frequency and collocation throughout the original novel, not so are its translations.

One issue follows from the ambiguity of the coordinating conjunction ‘and’ in the occurrence ‘a spare parlour and bedroom’, which does not make it possible to determine whether spare refers to the parlour only or to both the parlour and the bedroom. This is complicated even further by the fact that, no matter how it is translated, the English pre-modifier spare necessarily becomes a post-modifier in Italian. The translations considered here4 range from ‘di riguardo’ (for special occasions), and ‘di riserva’ (extra) to ‘per gli ospiti’ (for guests). The translation of spare with ‘riservato’ (reserved) would also be a feasible option, just as ‘spoglio’ (bare) or ‘spartano’ (spartan, basic) would be conceivable in this context. However, none of the translators chooses these latter options, and some prefer to simplify things by omitting spare altogether, whereas others modify the ambiguity implicit in the conjunction ‘and’ by inverting the order of constituents:

Spare omission:

un salottino e una camera da letto (Pozzo Galeazzi, 1951; D’Ezio, 2011)

[a small parlour and a bedroom]

il salotto e una camera da letto (Spaventa Filippi, 1956; Lamberti, 2008)

[the parlour and a bedroom]

Ambiguity inversion:

un salotto e una stanza da letto di riguardo (Dettore, 1974)

[a parlour and a guest room]

un salottino e una camera da letto di riserva (Gallenzi, 1997)

[a small parlour and a spare bedroom]

un salottino e una camera di riserva (Sacchini, 2014)

[a small parlour and a spare room]

il salottino e una stanza per gli ospiti (Capatti, 2013)

[the small parlour and a guest room]

un salottino e una camera per gli ospiti (Pareschi, 2014; Manini, 2019)

[a small parlour and a guest room]

Explicitation:

un salotto che non veniva mai usato e una camera per gli ospiti (Reali, 1996)

[a parlour that was seldom used and a room for guests]

In the inversions, the postmodifying prepositional groups ‘di riguardo’, ‘di riserva’, and ‘per gli ospiti’ certainly refer to the bedroom but, because of the inherent ambiguity of the conjunction and (‘e’ in Italian), they might also refer to the parlour. In English it is the other way round (i.e., the parlour is certainly spare, the bedroom might or might not be spare as well, depending on the reader’s interpretation). Reali is the only one to eliminate the ambiguity by making the postmodification explicit: therefore — and not without reason — she interprets spare as referring to both the parlour and the bedroom. To sum up, whether because it was misprinted in the source text, or because of the asymmetries between English premodification and Italian postmodification, in Charlotte Brontë’s masterpiece the adjective spare has a tendency to get either lost or misrepresented in translation.

Square presents completely different characteristics. It occurs fifteen times (sixteen if you include the red room), of which one is the comparative squarer, and another is the abstract noun squareness. It is never used to describe the shape of rooms — with only one exception. Much more poignantly, it serves the purpose of metaphorically (and skilfully) pointing to the hard-edged nature of some characters in the novel. Mrs Reed is the first one to be described in such terms:

she was a woman of robust frame, square-shouldered and strong-limbed, not tall, and, though stout, not obese […].5

Then there is Mr Brocklehurst, whose squareness is to be found not so much in his appearance — when little Jane is convened to meet him, all she sees is a ‘black pillar’ — as in what he does when he faces her at Gateshead. Such action suits him perfectly:

he placed me square and straight before him. What a face he had, now that it was almost on a level with mine! what a great nose! and what a mouth! and what large prominent teeth!6

St John Rivers is another character associated with the word square. Given his austere nature, it is not surprising that, while suppressing what appears to be full-fledged jealousy for his beloved Rosamond Oliver, his face should take on some squareness as well:

Mr St John’s under lip protruded, and his upper lip curled a moment. His mouth certainly looked a good deal compressed, and the lower part of his face unusually stern and square […].7

It is at Thornfield, though, that the word square occurs most often. The reference is to Rochester’s forehead and his masculine jaw, of course, but also to Thornfield itself, its inhabitants — Grace Poole — and its objects, tokens of Rochester’s failed wedding attempt. It is also here — as Jane enters the property for the first time — that the only use of square to describe a room occurs, justified by the need to emphasize the magnificence of the hall:

I followed her across a square hall with high doors all round […].8

However, it is Rochester who is primarily described in terms of squareness:

The fire shone full on his face. I knew my traveller with his broad and jetty eyebrows; his square forehead, made squarer by the horizontal sweep of his black hair. I recognised his decisive nose, more remarkable for character than beauty; his full nostrils, denoting, I thought, choler; his grim mouth, chin, and jaw — yes, all three were very grim, and no mistake. His shape, now divested of cloak, I perceived harmonised in squareness with his physiognomy: I suppose it was a good figure in the athletic sense of the term — broad-chested and thin-flanked, though neither tall nor graceful.9

Again:

My master’s colourless, olive face, square, massive brow, broad and jetty eyebrows, deep eyes, strong features, firm, grim mouth — all energy, decision, will — were not beautiful, according to rule; but they were more than beautiful to me.10

Even at Gateshead, when Jane visits Mrs Reed on her deathbed, Rochester’s image looms with the squareness of his lineaments:

One morning I fell to sketching a face: what sort of a face it was to be, I did not care or know. I took a soft black pencil, gave it a broad point, and worked away. Soon I had traced on the paper a broad and prominent forehead and a square lower outline of visage: that contour gave me pleasure; my fingers proceeded actively to fill it with features […]. I looked at it; I smiled at the speaking likeness: I was absorbed and content.

‘Is that a portrait of some one you know’ asked Eliza, who had approached me unnoticed. I responded that it was merely a fancy head, and hurried it beneath the other sheets. Of course, I lied: it was, in fact, a very faithful representation of Mr Rochester.11

Grace Poole too, a Thornfield inhabitant herself, has a square figure, as Jane points out not once but twice in her narrative:

The door nearest me opened, and a servant came out — a woman of between thirty and forty; a set, square-made figure, red-haired, and with a hard, plain face: any apparition less romantic or less ghostly could scarcely be conceived.12

Mrs Poole’s square, flat figure, and uncomely, dry, even coarse face.13

The remaining squares are tokens of the failed wedding attempt: the square of blond that Jane had prepared as a head-covering for the ceremony (in contrast to the rich veil supplied by Mr Rochester and torn by Bertha), and the ‘cards of address’ where the newly-weds’ luggage was supposed to be sent:

The cards of address alone remained to nail on: they lay, four little squares, in the drawer.14

I thought how I would carry down to you the square of unembroidered blond […].15

She was just fastening my veil (the plain square of blond after all) […].16

Finally, in light of these occurrences, the fact that the word square should be used in connection with another rigid and hard-edged character like Eliza Reed acquires a deeper meaning. She is not described as square herself but, as her mother is lying on her deathbed upstairs,

three hours she gave to stitching, with gold thread, the border of a square crimson cloth, almost large enough for a carpet.17

Such unwieldy square crimson cloth may well be the objective correlative to her personality, and its colour a subtle reminder of the spare room in the house.

From the point of view of translation, the word square finds a straightforward enough equivalent in the Italian ‘quadrato’ (noun, adjective) and ‘squadrato’ (adjective). Notwithstanding, their occurrence is not always consistent and, unfortunately, the word disappears altogether in the translation of the expression square and straight (‘he placed [Jane] square and straight before him’, Chapter 4) into Italian, variously rendered as just ‘dritta’ (straight) in Dèttore, Gallenzi, Capatti, and Pareschi; ‘dritta impalata’ (straight and stock-still) in Sacchini; ‘proprio’ (right) in Pozzo Galeazzi, Reali, Lamberti, D’Ezio and Manini; and altogether omitted in Spaventa Filippi ‘egli mi pose dinanzi a lui’ (he placed me before him).

Nonetheless, on the whole, these significant instances of squareness come through strongly in Italian Jane Eyres: ‘square’ not only edges out ‘spare’ from the red room, but makes itself squarely felt throughout the translations.

The 1897 Service & Paton Edition

By comparing the 1897 edition with the manuscript and early editions, several divergences emerge. These mostly concern spelling variations and do not generally involve any substantial difference or malapropism. However, in addition to the replacement of spare by square in Chapter 2, there are three more cases that appear noteworthy.

The first occurs towards the end of Chapter 6, in Helen’s outline of her doctrine of acceptance and hope, according to which there is no point in letting oneself being burdened by the faults of this world if, some day, what will remain of our mortal flesh is only ‘the impalpable principle of life and thought’ (MS 43474, vol. I, fol. 93r and the first four editions). In the 1897 Service & Paton edition, life becomes light. The reverberations of this substitution, which can also be found in the 1933 Oxford edition, are far-reaching in terms of translation, with half the translators replacing ‘vita’ (life) with ‘luce’ (light): Pozzo Galeazzi, Dettore, Capatti, Sacchini and Manini.

In Chapter 12, just before Rochester and Jane meet for the very first time, Jane sees from afar Rochester’s horse approaching on the solitary road, then perceives his big dog: ‘it was exactly one mask of Bessie’s Gytrash — a lion-like creature with long hair and a huge head’. The discrepancy concerns the replacement of the original mask (to be found in the manuscript and first four editions) with form in the 1897 edition. Indeed, Charlotte Brontë had just mentioned — in the preceding paragraph — that the Gytrash ‘comes upon belated travellers in the form of a horse, mule, or large dog’. Form, in this particular context, can be considered the generic hypernym of the more specific hyponym mask, with the former referring to the form of the body and the latter to the mask one wears on the face.18 Brontë’s unusual use of ‘mask’ here, which is not attested in the OED, must mean something like ‘avatar’ or ‘manifestation’, but still suggests, in Jane’s perception, an actual Gytrash wearing a mask — which is a lot more frightening than the mere resemblance of a form. With the shift from mask to form, the 1897 edition thus loses some intensity in the suspense of the scene.

In the translations, however, this difference becomes blurred, since the translators tend to use more indefinite expressions such as ‘copia’ (copy) or ‘immagine’ (image), for example in Dèttore and Manini:

Era la copia esatta di una delle personificazioni del Gytrash di Bessie (Dèttore, 1974)

[it was the exact copy of one of the personifications of Bessie’s Gytrash]

Era un’immagine esatta del Gytrash di Bessie (Manini, 2019)

[it was an exact image of Bessie’s Gytrash]

Only D’Ezio (albeit with an omission), Pareschi, and Sacchini express how it was not merely ‘an exact image’ or ‘a copy’, but rather the actual Gytrash:

Era esattamente il Gytrash di Bessie (D’Ezio, 2011)

[It was exactly Bessie’s Gytrash]

Era esattamente una delle personificazioni del Gytrash (Pareschi, 2014)

[It was exactly one of the Gytrash’s personifications]

Era proprio uno dei travestimenti del Gytrash di Bessie (Sacchini, 2014)

[It was indeed one of the costumes of Bessie’s Gytrash]

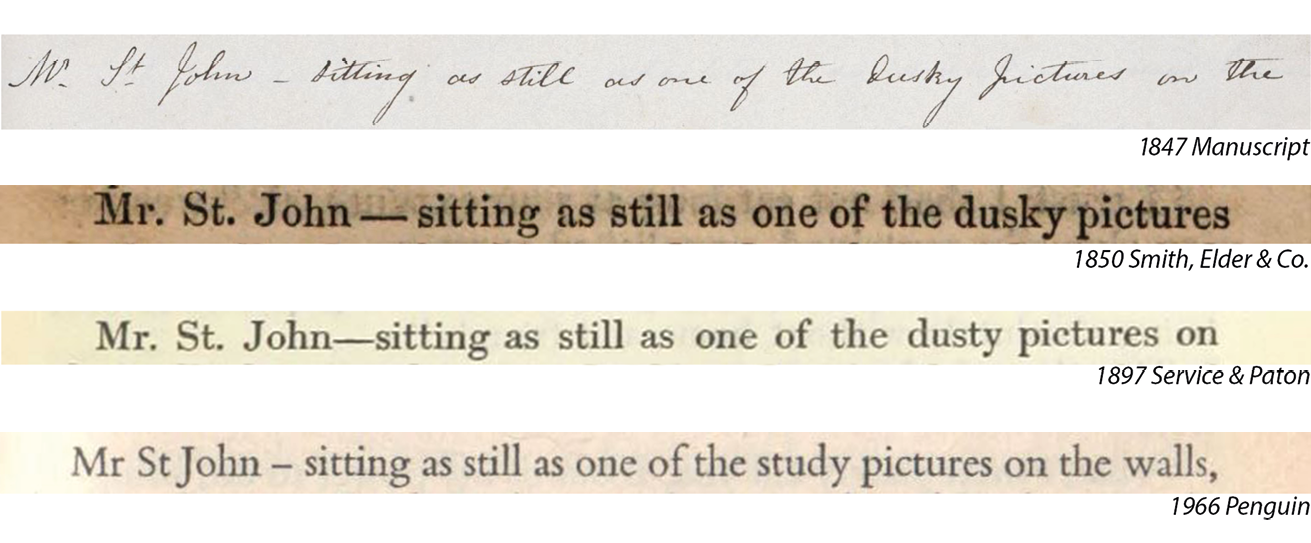

The other noteworthy difference between the 1897 edition and the manuscript and first four editions is interesting because it also affects all Penguin editions (1966, 2006 and 2015). In Chapter 29, when Jane speaks to St John for the first time after recovering from her four-day wanderings, he is depicted as ‘sitting as still as the study pictures on the walls’. Study here is inappropriate: for one, Jane and St John are in the parlour, not in the study, and even if its reference were not to a room, the meaning of study would remain unclear. It simply is not the word used by Charlotte Brontë, and this also explains why so many translators prefer to omit it altogether.

The 1897 edition makes more sense: St John is here ‘sitting as still as one of the dusty pictures on the walls’. It does seem quite likely that St John should appear dusty — at least in countenance. However, the 1847 manuscript, and the four first editions all read neither study nor its anagram dusty, but dusky. This matters because it shifts the description to the realm of colours, rather than that of location or of sloppiness in house cleaning.

Fig. 2 Dusky pictures. Images of the manuscript (London, British Library, MS 43476, vol. III, fol. 84r), the 1850 edition (London: Smith, Elder & Co., p. 353) and the 1897 edition (London: Service & Paton, p. 331) are courtesy of the © British Library Board. The 1850 edition was digitised by the Google Books project.

As in a piece of classical music, there are here three variations on the theme — the theme being St John sitting still, the variations being the similes. In Italian, ‘polveroso’ (dusty) can be found in Capatti, Pareschi and Sacchini. A few, like Lamberti, D’Ezio and Manini, omit the word altogether. Dusky is aptly translated as ‘scuri’ (dark), by Pozzo Galeazzi and Dettore; as ‘anneriti’ (blackened), by Reali; and as ‘cupi’ (sombre), by Gallenzi.

The Penguin Editions (1966, 2006 and 2015)

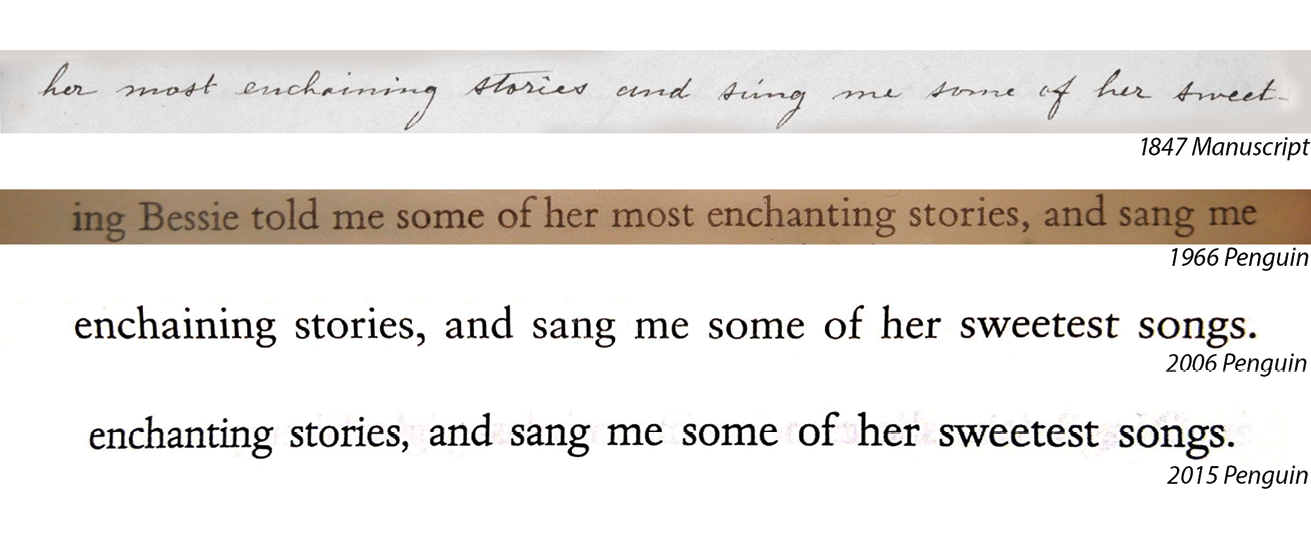

As already shown, the Service & Paton 1897 edition is not the only one to contain imprecisions. The Penguin editions have their share too. In addition to the replacement of dusky with study in Chapter 29, and the replacement of enchaining with enchanting in Chapter 4, which we will explore in the next section, there are a few more striking malapropisms.

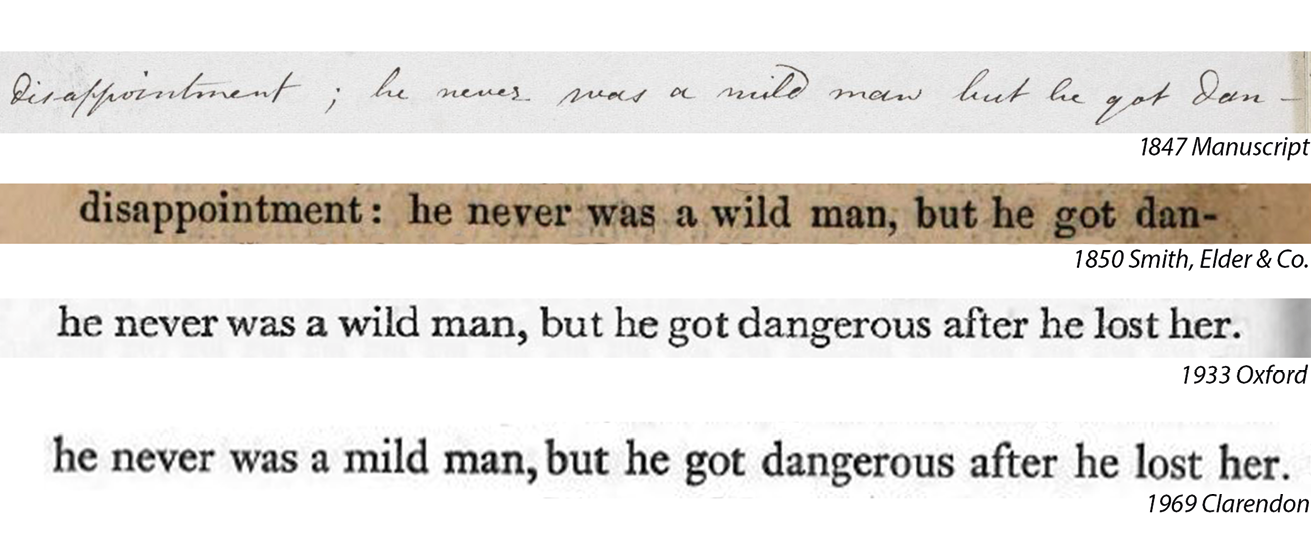

In Chapter 36 of all Penguin editions, when Jane is being told by the inn’s host about the misfortunes that befell Thornfield and its inhabitants, and specifically about Rochester’s reaction when he lost Jane, ‘the most precious thing he had in the world’, the host adds that ‘he never was a mild man’. Penguin was not the only one to prefer mild over wild: the authoritative 1969 Clarendon edition does the same.19

Fig. 3 A wild man. Images of the manuscript (London, British Library, MS 43476, vol. III, fol 225r) and the 1850 edition (London: Smith, Elder & Co., p. 440) are courtesy of the © British Library Board. The 1850 edition was digitised by the Google Books project.

That Rochester was never mild in nature is well understood by the readers as well as by the characters in Jane’s story. But he was not altogether wild either, at least not until Jane’s departure — and that is what the host is pointing out. After losing her, Rochester did become wild — and utterly so — to the point of being dangerous, as ‘he grew savage, quite savage on his disappointment’.

The first four editions, just like the manuscript and several others,20 up to the recent 2019 Collins Classics edition, all read: ‘he never was a wild man, but he got dangerous after he lost her’. Yet, in the Penguin editions, the original adjective wild is replaced by its antonym. This may be a slip, but it might also be a deliberate choice, like that made by the Clarendon editors Jane Jack and Margaret Smith. These mutations in the English source text do bear consequences in the translations: ‘un uomo mite’ (a mild man) can be found in Spaventa Filippi, Reali, Gallenzi, Lamberti, D’Ezio and in the most recent 2019 translation by Luca Manini. Pozzo Galeazzi emphasizes Rochester’s mildness even more: ‘egli era sempre stato un uomo tranquillo’ (he had always been a tranquil man). From never wild to always mild — that is quite a leap.

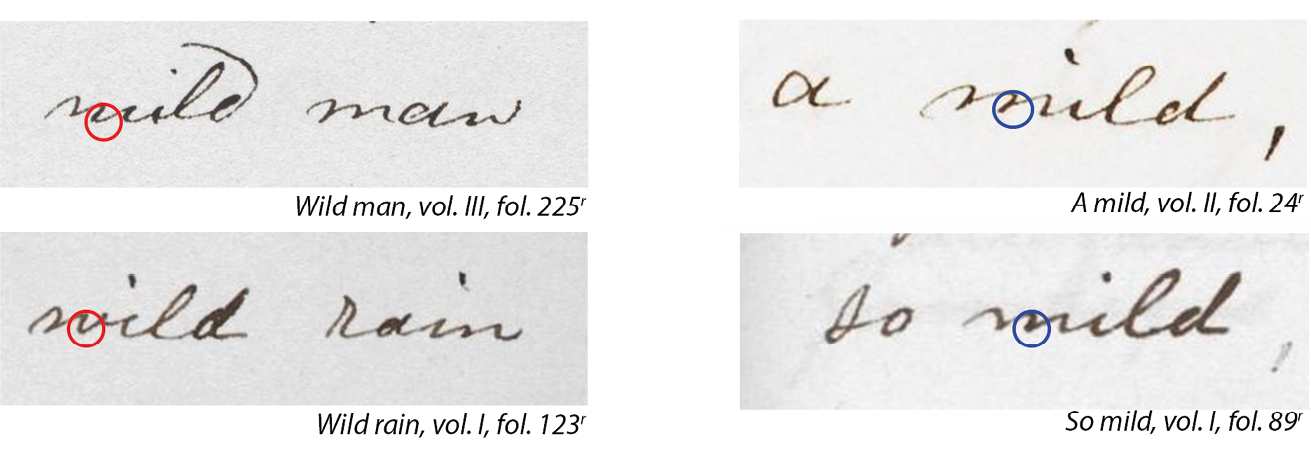

For the sake of complete disclosure, it should be pointed out that the manuscript’s handwriting of wild (MS 43476, vol. III, fol. 225r) might easily be confused with mild — which was at the basis of the Clarendon editors’ choice to replace it with mild.21 However, by comparing wild in ‘a wild man’ with random occurrences of both mild and wild in the same manuscript, the difference — however subtle — does appear.22 That Charlotte Brontë never meant to write mild is also supported by her never amending any of the first three editions (all of which read wild).

Fig. 4 Wild and mild. London, British Library, MS 43474, vol. I, fol. 89r and 123r; MS 43475, vol. II, fol. 24r; MS 43476, vol. III, fol. 225r, courtesy of the © British Library Board.

Another Penguin variation occurs in Chapter 30, when St John offers to help Jane by appointing her as the mistress of the new girls’ school, and asks her to recall his ‘notice, early given, that if I helped you, it must be as the blind man would help the lame’. All the other editions I have consulted, as well as the manuscript, read clearly, not early. This bears consequences for a substantial number of translations, as Pozzo Galeazzi replaces clearly with ‘già’ (already), Speranza Filippi with ‘subito’ (right away), Lamberti, D’Ezio and Sacchini go with ‘dall’inizio’ (since the beginning) and similarly Manini provides a temporal specification with his ‘un giorno’ (some day). Although less conspicuous, worth mentioning are also the replacements of ‘no signal deformity’ with ‘no single deformity’ in Chapter 7, of ‘threading the flower and fruit parterres’ with ‘trading the flower and fruit parterres’ in Chapter 23 and of ‘hazarding confidences’ with ‘hazarding conferences’ in Chapter 27.

The Project Gutenberg File

Once so many differences have come to the surface in the print editions, it seems natural to wonder whether anything of the sort can also be observed in the Project Gutenberg file — i.e., in the digitized version of the 1897 Service & Paton edition — which, as already mentioned, was first released in 1998, the current release dating to 2007. As with the other editions considered, variations in spelling and obvious typos (e.g., quiet → quite) have but little relevance. What is of greater interest are meaning-bearing changes, especially malapropisms. In the Gutenberg file, there are a few such cases, listed here in order of occurrence.

The first one is in Chapter 4 and has a rather hilarious effect: John Reed, scared of Jane’s aggressive reaction, runs away from her — not ‘uttering execrations’, as in the manuscript, but ‘tittering execrations’.

Then, the words enchanting (in ‘enchanting stories’, Chapter 4) and enchanted (in ‘enchanted my attention’, Chapter 7) — which at first sight do not attract any attention because of the common collocation of both enchanting + stories and enchanted + attention — are in fact a substitution for the ‘enchaining stories’ and ‘enchained my attention’ of the original manuscript. This is interesting, because there are also some print editions, such as the 2019 Collins Classics, which mistakenly replace the verb to enchain with to enchant in ‘enchaining stories’. The 1966 Penguin edition had ‘enchanting stories’ but it was afterwards replaced with the correct ‘enchaining stories’ in 2006. Unfortunately, Penguin went back to ‘enchanting stories’ in 2015. Likewise, the translations tend to maintain the enchanting version, as for example that by Manini, which reads ‘storie incantevoli’ (enchanting stories). Though the change in meaning is not dramatic, still such substitutions reveal the tenuous yet salient difference between narrative commonplace and stylistic mastery.

Fig. 5 Enchaining stories. The image of the manuscript (London, British Library, MS 43474, vol. I, fol. 61r) is courtesy of the © British Library Board.

The next variation occurs in Chapter 21, when Jane goes back to Gateshead to visit her dying aunt. There, Jane finds her cousins Georgiana and Eliza, who have by now developed incompatible personalities. As Eliza speaks harshly to her sister, she advises her to ‘suffer the results of [her] idiocy, however bad and insuperable they may be’. Those results are indeed not insuperable — as in the Gutenberg file — but insufferable, as in the 1897 Service & Paton edition and in the 1847 manuscript.

In Chapter 27, Rochester tells Jane about his unsuccessful chase after true love, and, in the Gutenberg edition, he says ‘I was presently undeserved’ — as if he were himself a prize not deserved by the women he fell for. The effect is totally different from the original undeceived, meaning that Rochester’s expectations to find a soulmate were repeatedly disappointed.

An even more substantial case can be observed in Chapter 34. The context is St John’s marriage proposal to Jane. As she contemplates his words, Jane finally comprehends him and understands his limits: ‘I sat at the feet of a man, erring as I’. St John’s arduous crusade to save humanity — possibly with Jane as wife — is based exactly on this, on the fallibility of the human race and his wish to make amends, to atone for original sin. If, at this very moment, Jane realizes the true nature of St John by perceiving him as a flawed human being, in the Gutenberg file such human fallibility is transformed into affection: in an ironic twist, ‘erring as I’ becomes ‘caring as I’.

Further cases worth mentioning are: the replacement of ‘flakes fell at intervals’ with ‘flakes felt it intervals’ in Chapter 4; ‘by dint of’ becomes ‘by drift of’ in Chapter 11; the transformation into muffed to be found in Chapter 15, when Rochester does not hesitate to recognize his unfaithful Céline ‘muffled in a cloak’; the ‘sweetest hues’ to be used by Jane for Blanche Ingram’s portrait become ‘sweetest lines’ in Chapter 16; the change from shake to shade in St John’s confession to Jane about his feelings for Rosamond (‘when I shake before Miss Oliver, I do not pity myself’, Chapter 32); in Chapter 35, malice is replaced by force in the expression ‘by malice’; and blent becomes blest in Chapter 37.

Finally, there are a few omissions: of the word small in a ‘small breakfast room’ in Chapter 1; of ‘ear, eye and mind were alike’ in Chapter 3; of necessary in ‘thoughts I did not think it necessary to check’ in Chapter 17; of Jane’s words to Rochester ‘quite rich, sir!’ in Chapter 37.23

Even though some of these variations occur in other editions as well, they are relevant here because they diverge from the 1897 edition, on which the Gutenberg file is based, and are therefore to be considered consequences of a faulty passage from paper to digital format.

Errors Common to Most Editions

The red room is a mysterious place indeed. Strange things happen there, not only in the context of the development of the story, but also in its textual detours. The one which spurred this research has been extensively discussed, with the square room error inevitably projected into the translations — in a reflection game not dissimilar from what Jane experiences by looking into the mirror when she is locked up in there. Towards the end of Chapter 2, there is another anomaly, and this time it affects most editions, anglophone or otherwise. It is an omission fraught with meaning because it makes the red-room scene even more surreal than it actually is. This is the excerpt from the manuscript: ‘I was oppressed, suffocated: endurance broke down — I uttered a wild, involuntary cry’ (MS 43474, vol. I, fol. 20r). This last clause, ‘I uttered a wild, involuntary cry’, is omitted in the first edition and is not amended in the following ones. The consequence is that what happens next in the scene loses coherence, because it is supposed to be Jane’s screaming that attracts Bessie and Abbot’s attention and makes them run to check in on her. Without this clause, Abbot’s words ‘What a dreadful noise!’ would not make sense, unless such noise were caused by a ghost or some other supernatural creature (this could easily be expected in a haunted place like the red room, but it is not in fact the case). This clause remained omitted both in Great Britain (first four editions, 1897 Service & Paton, 1908 J.M. Dent & Sons, 1933 Oxford edition, 1966 Penguin edition) and in the United States (1848 Harper & Sons, 1943 Random House, 1969 Cambridge Book Company, 2003 Barnes & Noble, the first three Norton Critical editions — the list is not exhaustive). The error was clearly pointed out in the Clarendon edition, but not all publishers followed suit. It still remains omitted, for example, in the Collins Classics editions as well as in most translations — with the exceptions of Gallenzi, Sacchini and Manini.

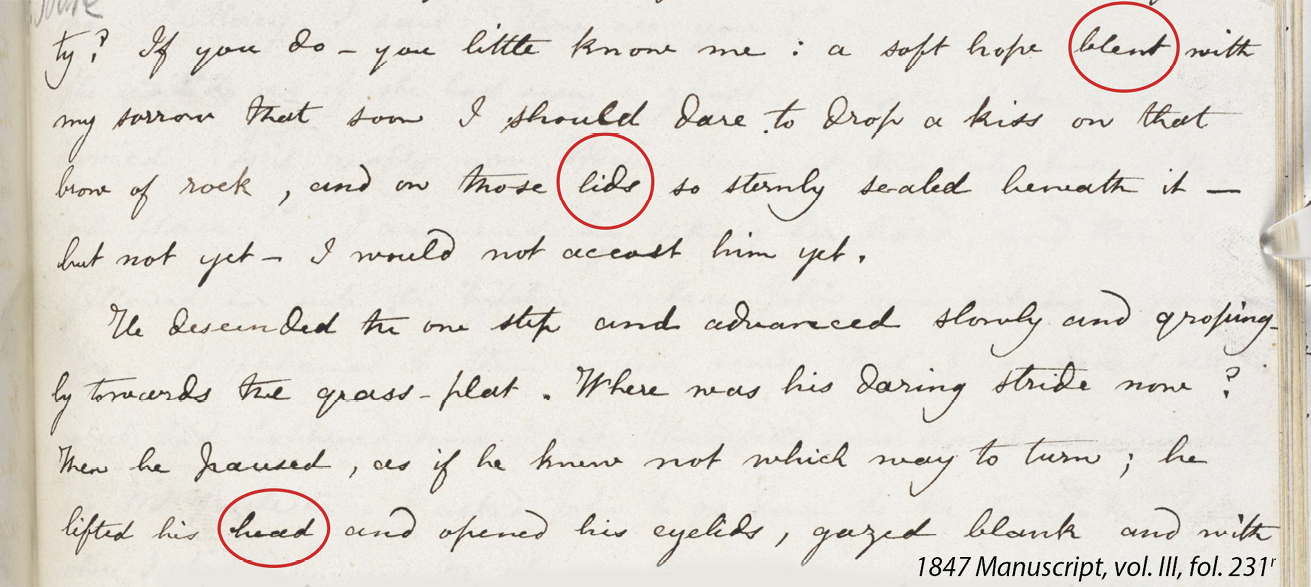

At the beginning of the penultimate chapter (37), Jane is about to be reunited with Rochester and observes him from a distance. She addresses the reader by asking whether we believe Rochester’s blind ferocity scared her at all. It does not:

A soft hope blent with my sorrow that soon I should dare to drop a kiss on that very brow of rock, and on those lips so sternly sealed beneath it […]. He lifted his hand and opened his eyelids.

This passage is peculiar: it contains three variations within just a few lines, and two of them concern most anglophone editions, hence most translations. The first one has already been mentioned and pertains to the Gutenberg file (‘a soft hope blest with my sorrow’): it resurfaces again in the Italian translation by Sacchini, in which Jane’s hope is ‘sacra’ (blessed). The second one follows immediately and is reproduced in most English editions. It has to do with where Jane wants to kiss Rochester after kissing his brow. Beneath the brow, there are Rochester’s eyes and lids, not his lips, and it is his lids that are so sternly sealed because of the injuries he suffered: his lips can open all right. The Clarendon edition specifies how the error arose in the second edition and was repeated in the third. The fourth perpetuated the error, which inevitably spread in time and space. Lips is to be found, among others, in: 1897 Service & Paton, 1906 The Century & Co., 1908 J. M. Dent & Sons, 1911 G. Bells & Sons, 1933 Oxford University Press, all Penguin editions, all Collins Classics, all Norton Critical Editions.24 It is no surprise that ‘labbra’ (lips) is in all the translations, the only exception being Reali, who writes ‘palpebre’ (lids).

The third variation also refers to Rochester’s maimed physicality and, like the previous one, is a direct consequence of a misprint which can be traced back to the first edition — as pointed out in the notes to the 1969 Clarendon edition. The result is a slightly graphic scene where Rochester rises his hand to pry his eyelids open. The truth is that he simply lifts his head and then opens his eyes, without any help from his hand — as in the manuscript: ‘he lifted his head and opened his eyelids’. Just like the previous case, this same error shows up in most anglophone editions and Italian translations, with only Reali and Gallenzi getting it right.

Fig. 6 Blent, lids and head. London, British Library, MS 43476, vol. III, fol. 231r, courtesy of the © British Library Board.

Insights into Translations Based on Non-Negligible Patterns

In general, it can be hard to be certain whether a variance in a translation derives from a similar variance in the source text or has been introduced by the translator: such is the fluidity that is always available in translation. However, when patterns emerge, claims can be ventured. The claims put forward in this section are that Stella Sacchini and Monica Pareschi both used the Gutenberg file as their main source text, and that the translation by Luca Lamberti is strongly based on Spaventa Filippi’s. Debatable as they may be, these claims result from the observation of a pattern arising from a non-negligible consistency in the anomalies of the texts at stake. In spite of the plethora of alternative translations of the same text (after all, translation is a never-ending task), there are some crucial words and expressions that either give away the influence from previous translations or reveal what source texts were used.

In Stella Sacchini’s prize-winning translation (2014), the following signs suggest that her work may have been directly affected by the Project Gutenberg file:

Ch. 1: omission of small in ‘a small breakfast room’ (Sacchini’s is the only translation to omit the adjective, as the Gutenberg file does);

Ch. 2: replacement of spare with square (‘quadrata’) in the red-room episode;

Ch. 6: replacement of life with light (‘luce’);

Ch. 16: replacement of hues with lines (‘linee’ — hers is the only translation to be faithful to the Gutenberg file);

Ch. 21: insufferable becomes insuperable (‘insormontabili’ — the only instance among the translations);

Ch. 29: dusky is replaced by dusty (‘polverosi’);

Ch. 37: replacement of blent with blest (‘sacra’ — again, the only instance among the translations to be faithful to the Gutenberg file); replacement of head with hand (common to most translations); replacement of lids with lips (common to most translations).

In the cases above, Sacchini’s are all faithful translations of the variations as they appear in the Gutenberg text: some pertain exclusively to it, while some are common to other editions as well. However, the influence exerted by the Gutenberg version on her text is limited to these instances, which suggests that she did also refer to other source texts or translations.

Another translation that appears to have suffered from the same influence is that by Monica Pareschi: according to her unique interpretation — and perfectly in line with the Gutenberg transcription — St John is caring (‘capace di affetti’) rather than erring; he does not shake before Miss Olivier, but shades before her (‘mi faccio scuro’); the stories are ‘più belle’ (more beautiful, which is a loose translation of enchanting) rather than enchaining; and — here again — St John sits still like ‘polverosi’ (dusty) pictures, not dusky ones. Like most translators, she omits “I uttered a wild, involuntary cry” in Chapter 2, and replaces lids with lips and head with hand in Chapter 37, all of which are consistent with, although not exclusive to, the Gutenberg file.

Then there is the case of the one-of-a-kind translator ‘Luca Lamberti’: this is not a real person but rather the nom de plume of a variety of translators working anonymously for the publishing house Einaudi, one of the most prestigious in Italy.25 What is peculiar about him — besides the undetermined authorship — is that he repeats some of the idiosyncratic phrasings used by Lia Spaventa Filippi. The anomaly emerges with suggestive precision in those strings of text where Spaventa Filippi tends to creatively paraphrase the source text rather than provide a word-for-word translation. In Chapter 3, the source text reads ‘ear, eye and mind were alike strained by dread’: she does not mention the ear, the eye nor the mind (which all other translators do), but summarizes the expression with a concise ‘i miei sensi’ (my senses). Lamberti uses the same wording.

Spaventa Filippi translates ‘his gripe was painful’ (Chapter 27), with an unusual ‘sotto la sua stretta’ (under his grip), thus transforming the subject into a prepositional phrase and omitting the adjective painful. Lamberti does the same. In Chapter 31, ‘perfect beauty is a strong expression; but I do not retract or qualify it’ is uniquely interpreted by Spaventa Filippi as ‘perfetta, per quanto forte possa sembrare questa espressione’ (perfect, no matter how strong this expression may seem), where the first part of the sentence is transformed by the addition of no matter how and of the verb to seem, while the second part is omitted. Such elaborate rewriting is echoed — again — by Lamberti. One last suggestive example is ‘a soft hope blent with my sorrow’ (Chapter 37), which Spaventa Filippi transforms into ‘la mia pena mi ispirava’ (my sorrow inspired me) — clearly a loose translation of the original, repeated verbatim by Lamberti.

Conclusion

If we merge all the source text variations, the spare room appears squarer and squarer; in that same room little Jane remains dumbstruck even as she is heard screaming out; Rochester is not that wild after all; and St John looks like a dusty and caring mortal soul, rather than a tragically dusky, erring one. Charlotte Brontë’s mid-nineteenth-century masterpiece has gained new features as a consequence of the inevitable imprecisions stemming from reproduction techniques such as printing, transcription, optical character recognition processes and indeed translations into whatever language. These are not necessarily mistakes or degradations though, since involuntary imprecisions or intentional translatorial choices can actually be ameliorative of the original — at least in theory, and assuming universally acknowledged quality standards can be set.26 Besides, it was because, at some point in time, spare was replaced by square, that the scattered yet meaningful occurrences of the word square have come to the forefront, lending the novel as a whole an extra shade of squareness, and not only the red room.

Textual variations simply mean that novels can and do develop well beyond the borders of the author’s manuscript. The claim that texts have a life of their own was never truer than in the cases analysed here. And each translation is indeed different from the others, no matter the degree to which it may have been influenced by the previous ones: they do change incessantly, but the most basic reason for such variety is that the source text itself varies, as it appears to be slowly evolving or devolving. Not all errors are horrors, though, and perhaps it cannot even be asserted that one edition or translation is ultimately better than the others, or that the digital revolution is to be blamed for perpetuating the horror of the square chamber (malapropism intended). If anything, the digital turn in the humanities, whose full potentialities are still being uncovered, represents a breakthrough in the study of the novel.

Texts are always characterized by their own idiosyncrasies and tend to be susceptible to improvement. Any novel and any translation, not unlike all things human, is subject to amelioration. In fact, because of their very nature, complex human endeavours — like human beings themselves — are defined much less by perfection and a lot more by perfectibility, and that striving is precisely what history — and scholarship — are made of.

Works Cited

For the translations of Jane Eyre referred to, please see the List of Translations at the end of this book.

Eco, Umberto, Dire quasi la stessa cosa: Esperienze di traduzione (Milano: Bompiani, 2003).

Ferrero, Ernesto, ‘Il più longevo, prolifico e poliedrico traduttore dell’Einaudi’, in Tradurre. Pratiche, teorie, strumenti, 11 (2016),https://rivistatradurre.it/2016/11/il-piu-longevo-prolifico-e-poliedrico-traduttore-delleinaudi

The Victorian Web, http://www.victorianweb.org

English-Language Editions of Jane Eyre

Brontë, Charlotte, Jane Eyre, manuscript, MS 43474–6, vol. I–III (London: British Library, 1847).

—— (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1848).

—— (London: Smith, Elder & Co., 1850).

—— (London: W. Nicholson & Sons, 1890).

—— (New York: Thomas Y. Crowell & Company, 1890).

—— (London: Service & Paton, 1897).

—— (New York and London: Harper & Brothers Publishers, 1899).

—— (New York: The Century Co., 1906).

—— (London and Toronto: J.M. Dent & Sons; New York: E.P. Dutton & Co.,1908).

—— (London: G. Bell & Sons, 1911).

—— (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1933).

—— (New York: Random House, 1943).

—— (London: Penguin, 1966).

—— (New York: Cambridge Book Company, 1969).

—— (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1969).

——, A Norton Critical Edition (New York and London: W. W. Norton Company, 1971).

——, 2nd Norton Critical Edition (New York and London: W. W. Norton Company, 1987).

—— (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000, 2008).

——, 3rd Norton Critical Edition (New York and London: W. W. Norton Company, 2001).

—— (London: Penguin, 2006).

—— (Gutenberg Project, 1998, 2007), https://www.gutenberg.org/files/1260/1260-h/1260-h.htm.

—— (London: Collins Classics, 2010).

—— (London: Penguin, 2015).

——, 4th Norton Critical Edition (New York and London: W. W. Norton Company, 2016).

—— (London: Collins 2019).

—— (Seattle: Amazon Classics, 2019).

1 The vast majority of early anglophone editions do read spare, both in the UK (an exception is the 1933 Oxford edition, later amended) and in the USA. In this regard, it is interesting to notice that the 1848 Harper & Brothers edition, published in New York, is correct with regard to the spare room, but the red room is turned into a bedroom (‘the bed room was a spare chamber’). Square tends to become more common only in later American editions, such as the 2002 Dover Classics and the 2006 Borders Classics.

2 The Victorian Web also contributed to the increased exposure of the Gutenberg file, using it as its reference text (http://www.victorianweb.org/authors/bronte/cbronte/janeeyre/1.html).

3 ‘Det røde værelse var et kvadratisk rum’ (the red room was a square chamber).

4 For the purposes of the present research, eleven unabridged translations have been selected, all currently available on the market. Of these, Alessandro Gallenzi’s 1997 translation, which is based on the 1980 Oxford University Press edition (as stated in the copyright page of his Jane Eyre, published by Frassinelli), follows the three-volume division — therefore chapter references used for the others do not apply to either Gallenzi’s translation or the Oxford editions (including the Clarendon one, but excluding the 1933 OUP edition) — unless the reference is to the chapters in the first volume (Ch. 1–15).

5 JE, Ch. 4.

6 Ibid.

7 JE, Ch. 34.

8 JE, Ch. 11.

9 JE, Ch. 13.

10 JE, Ch. 17.

11 JE, Ch. 23.

12 JE, Ch. 11.

13 JE, Ch. 14.

14 JE, Ch. 25.

15 Ibid.

16 JE, Ch. 26.

17 JE, Ch. 21.

18 Of the three occurrences of mask in Jane Eyre, two are associated with form and, in both cases, there is a hyponymy-hypernymy relation between the two. Besides the Gytrash’s mask, the other occurrence is used to describe Bertha Mason’s features. Here as well, mask refers to the face (hyponym) and form to the body (hypernym): ‘compare […] this face with that mask — this form with that bulk’ (in Ch. 26, soon after the failed wedding, when Rochester takes his guests to see for themselves who or what his wife was). In this case, though, the translations of mask and form are unanimously consistent and literal: ‘maschera’ and ‘forma’ (form) in Reali, Gallenzi, D’Ezio, Capatti; ‘maschera’ and ‘forme’ (forms) in Spaventa Filippi and Lamberti; ‘maschera’ and ‘figura’(figure) in Dèttore, Sacchini, Pareschi, Manini; and ‘maschera’ and ‘corpo’ (body) in Pozzo Galeazzi.

19 The Oxford Clarendon Press edition may have been the most authoritative, but it was not the first one, as the earliest occurrence of mild can be traced back at least to 1906, with the American edition The Century & Co., New York, p. 459. The 1966 Penguin edition also anticipates Jane Jack and Margaret Smith’s 1969 emendation.

20 1848 Harper & Brothers, 1908 Dents & Sons, 1911 G. Bells & Sons, 1933 Oxford University Press, all Norton Critical Editions, among others.

21 ‘The MS states that Mr Rochester “never was a mild man”, whereas the printed editions tell us that he “never was a wild man”’, in Charlotte Brontë, Jane Eyre, ed. by Jane Jack and Margaret Smith (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1969), p. xxi. In the note on p. 547, the editors again specify that mild is their reading of the manuscript. It goes without saying that, because of the authoritative standing of the Clarendon edition, it influenced not only the OUP editions to follow but also editors of other publishing houses, like Penguin itself, whose 1966 reading as mild was tacitly validated by Jack and Smith.

22 Figure 4 highlights the stroke that distinguishes the ‘w’ from the ‘m’, but — as Joseph Hankinson aptly pointed out when he read the first draft of this Essay — there is another interesting difference to be appreciated here: in Charlotte Brontë’s calligraphy, the letter ‘d’, especially but not exclusively at the end of a word, appears sometimes to be curved (as in wild man), sometimes straight (as in wild rain). Even though in mild the ‘d’ tends to be straight, this has no bearing on the wild/mild difference, as the alternative calligraphies happen for no obvious reason other than — probably — fluctuations in writing speed.

23 There are a couple more variants in this chapter, which are not specific to the Gutenberg file, and concern most editions: these are dealt with in the following section.

24 Not all editions perpetuate the error: the 1948 Harper & Brothers, New York, is correct, and so are the Oxford editions following the Clarendon amendment.

25 See Ernesto Ferrero, ‘Il più longevo, prolifico e poliedrico traduttore dell’Einaudi’, in Tradurre. Pratiche, teorie, strumenti, 11 (2016),https://rivistatradurre.it/2016/11/il-piu-longevo-prolifico-e-poliedrico-traduttore-delleinaudi/

26 In this regard, Umberto Eco devotes a section of his Dire quasi la stessa cosa: Esperienze di traduzione (Milano: Bompiani, 2003, pp. 114–25) to the possible improvements of a source text following misreadings that are sometimes intentional, sometimes not, but which can, in both cases, still be very poetic, and actually improve the source text. He does, however, warn against the dangers of misreading the original and advises against this sort of manipulation.