The General Map https://digitalkoine.github.io/je_prismatic_generalmap/ Created by Giovanni Pietro Vitali; © OpenStreetMap contributors

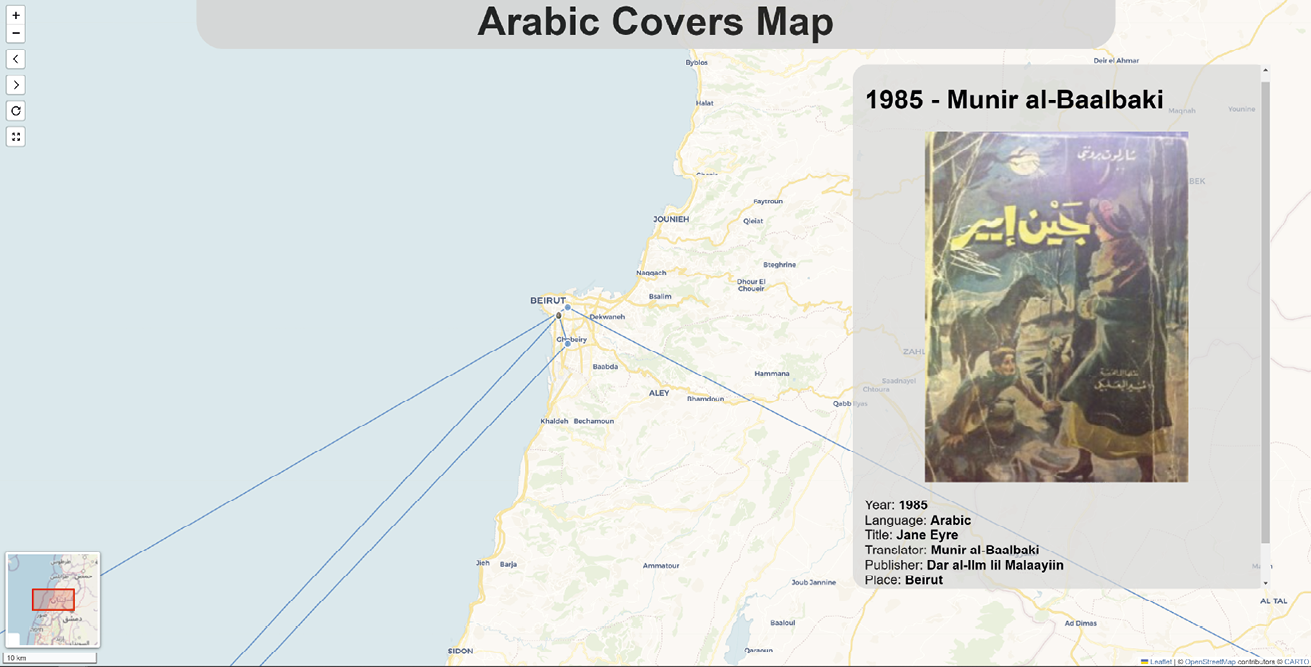

The Arabic Covers Map https://digitalkoine.github.io/arabic_storymap/ Researched by Yousif M. Qasmiyeh; created by Giovanni Pietro Vitali and Simone Landucci

3. Jane Eyre’s Prismatic Bodies in Arabic

© 2023 Yousif M. Qasmiyeh, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0319.06

This chapter explores the body in translation in Arabic versions of Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre.1 In doing so, I focus on three interpretations of the body: firstly, viewing Jane Eyre itself as a corpus which engenders more corpuses through translation across languages and genres; secondly, tracing the multiple Arabic renderings of the body’s name, Jane Eyre, in the context of naming and titling; and finally, through a focus on one material aspect of the body in the novel: touching. Throughout the chapter I am guided by Matthew Reynolds’s proposition that ‘[t]ranslation is inherently prismatic’, a view which ‘is alert to translation’s proliferative energies’ but also one that re-centres ‘the particularity of the language of the translation’.2 Moreover, in exploring the relationship between translation and the body, in particular through my discussions of naming and touching, I build on the work of Jacques Derrida and his specific attention to the body in his pivotal article ‘What Is a “Relevant” Translation?’.3 In this article, originally titled ‘Qu’est-ce qu’une traduction “relevante”?’,4 Derrida attempts to locate a ‘relevant translation’ by astutely attributing the act of religious conversion — in Shylock’s case from Judaism to Christianity — to the transformation of the body proper. Derrida’s essay has long been viewed as canonical in translation studies, and yet more recently its precise ‘relevance’ (as in pertinence) to translation studies has been queried. In particular, Kathryn Batchelor argues that the particular power of Derrida’s essay stems from his attention to the ‘multiplication of touches, caresses, or blows’ throughout translation, noting that it is the duty of undertaking ‘the movement between languages to open up multiple readings of the original text’ that should be of ‘far greater interest to today’s translation studies scholars than Derrida’s discussions of the traditional paradigm of translation’.5 What is of particular interest in this chapter is precisely the prismatic multiplication that arises through the movement between English and Arabic, and more concretely as it pertains to the body, in the case of Jane Eyre.

While Derrida notes that ‘any translation’ can be considered to ‘stand between… absolute relevance, the most appropriate, adequate, univocal transparency, and the most aberrant and opaque irrelevance’,6 throughout his essay, Derrida ‘prowl[s]’7 around the ‘inter- and multi-lingual’ term relevant,8 in particular through its French roots and connotations. In so doing, he ties relevance, translation and the body closely together by ‘describing [relevance] not simply as a “corps” [body] but as a “corps de traduction” [translative body]’:9

this word, ‘relevant’ carries in its body an on-going process of translation…; as a translative body, it endures or exhibits translation as the memory or stigmata of suffering [passion] or, hovering above it, as an aura or halo.10

In his essay, Derrida thus mainly talks about translation as a lifting away from the body (from the French relever),11 a movement from body to word. In turn, my chapter takes a step forward from Derrida by exploring translation in relation to new kinds of embodiment.

On the one hand, I build upon existing elements of Derrida’s oeuvre; for instance, as Derrida attributes to the title of his own essay,12 I would argue that the title of Jane Eyre, or even the entire corpus of Jane Eyre, has an ‘apparent untranslatability’ into Arabic, due to factors related to voice and materiality. On the other hand, I expand the remit of other elements underpinning Derrida’s essay. Most notably, perhaps, where Derrida concentrates on the ‘Abrahamic and post-Lutheran Europe[an]’13 traditions, and ‘insist[s] on the Christian dimension’14 of conceiving the body and translation, I focus on the distinctiveness of translation into Arabic and its related traditions. Like Derrida, my interest thus lies in the body, and yet working through the Arabic translations emphasises not only how the body in translation can emerge differently, but also how such translations are rendered accessible to audiences who may not have so ‘thoroughly assimilated the ideas and images of Christianity’ as Charlotte Brontë herself.15 Indeed, Jane Eyre has often been read through a specifically Christian frame of reference — as Brown Tkacz notes, there are 176 scriptural allusions, circa 81 and 95 quotations and paraphrases from the Old Testament and the New Testament respectively16 — and yet I suggest that a critical reading of Arabic translations must also acknowledge traditions that go beyond ‘the Christian dimension’.17 In essence, where Derrida posits the relevance of the Merchant of Venice to the concerns of translation, in my analysis of Arabic translations of Jane Eyre I make reference to the Qur’an and The Arabian Nights alike, thereby echoing the very duality in Jane Eyre, as a novel that refers repeatedly to the Bible (see also Essay 14 by Léa Rychen, below) and to the Arabian Nights themselves (representing transformative story-telling and self-fashioning).18 In drawing on these references, I seek to develop a view of the body in translation rooted in Arabic, in contrast to Derrida’s theory with its Judeo-Christian roots.

Another way in which I expand Derrida’s analysis is that where he views translation as ‘preserving the debt-laden memory of the singular body’,19 I develop a different line of argumentation by challenging the equation of translation with ‘preservation’ and, indeed, by highlighting the prismatic and pluralistic nature of bodies in translation.20 To do so, and echoing Batchelor’s recognition that it is precisely the ‘multiplication of touches, caresses, or blows’ that is of particular significance to translation,21 I divide my discussion as follows. Taking the corpus of Jane Eyre as my starting point, I begin by introducing the first radio adaptation (and, indeed, the first popular translation) of Jane Eyre in Arabic, examining how orality and narration in Arabic, and their employment in Arabic translations of Brontë’s text, usher in the birth of new versions which are themselves not direct equivalences, but ‘prismatic’ bodies in translation. Nūr al-Dimirdāsh’s 1965 radio adaption evidences the significance of voice and localisation, and in the second part of the chapter I examine how the importance of voice continues to figure in the print translations of Jane Eyre in Arabic, especially in the 1985 translation by Munīr al-Baʿalbakī. In particular, I focus on how translators have, in fluid ways, engaged with Jane Eyre’s genres, and on different written and voiced iterations of the name Jane Eyre in Arabic. Through my discussions of both the radio and printed translations, I thus complicate the distinction between speech and writing, or the binary of the oral and the written, instead noting that there can be elements of orality in writing, and, equally, ‘writtenness’ in oral performances. Finally, through an analysis of the different forms of touching and caressing the body, as written/voiced in the Arabic verbs employed in the various translations of the text, I emphasise the materiality of the body in translation, thereby complicating the positionality of the body proper in translation.

Orality as a Vehicle for Multiplicity

In the first section of this chapter, I examine Nūr al-Dimirdāsh’s 1965 serialised adaptation of Jane Eyre for the Egyptian national radio,22 inter alia highlighting the significance of the aural transmission of Jane Eyre on subsequent textual Arabic translations. Although the radio adaption was not the first translation per se into Arabic,23 in this chapter I focus on the first serialised radio adaption, given its broader significance as it reached a particularly wide and popular audience across the Arabic-speaking region. This is highly relevant given that access to the cinema and books alike was restricted by a range of socio-economic and educational barriers.24 In particular, I argue that al-Dimirdāsh’s version not only bridges the gap between Arabic and English, but, equally, is a medium through which the formal Arabic (Fuṣḥā) and the Egyptian vernacular have been reconciled, thereby demonstrating the complex relationship between writing and speech. At this stage, it is worth noting that, while its aim is not to offer a purely formal rendition of Jane Eyre, al-Dimirdāsh’s version nonetheless sheds light on diglossia within the Arab-speaking region and the rupture between the formal Arabic register (Fuṣḥā) and the many national dialects (lahajāt, sing. lahja) that are spoken across the region.25 Such a distinction is essential to our discussion, since Fuṣḥā has long been assigned to the written in Arabic, whereas lahja primarily refers to the spoken.26 In al-Dimirdāsh’s case, one might say that the Fuṣḥā-lahja dynamic is inverted: instead of employing the Egyptian vernacular in the transmission of the radio adaptation of Jane Eyre, he opts for Fuṣḥā with vernacular traces (as I discuss below) which can be easily detected by the listener and, as such, nationally located in the radio broadcast.27

It is not insignificant that, when Jane Eyre was transmitted to the Arab reader/listener regionally, it was transmitted through a serialised form completed not by a professional translator but by the Egyptian actor and director Nūr al-Dimirdāsh’s himself, who understood and spoke English, and enjoyed adapting and abridging world literature,28 to subsequently be voiced by first-class Egyptian actors and actresses, including Ḥamdī Ghayth and Karīma Mukhtār, and broadcast on the Egyptian national radio to acclaim.29 Radio, as a medium, was particularly significant during this period (part of Egypt’s ‘Radio Era’),30 since it provided access to people who would otherwise be unable (due to socio-economic and educational barriers, amongst other things) to read a translation.

Guided and inspired by Jerome’s Jane Eyre: A Drama in Three Acts (1938), and the novel itself, as announced by al-Dimirdāsh at the start of the broadcast, the adaptation was almost entirely performed in Fuṣḥā Arabic, notwithstanding some inflections that belong solely to the Egyptian vernacular, in particular those pertaining to the pronunciation of the letter/sound j (a highly significant sound, given the title and eponymous protagonist), which in the Egyptian vernacular is pronounced as a hard g.31 To provide two minor examples (the radio adaption is replete with such instances throughout), in the midst of an otherwise ‘formal’ sentence, the words ‘yagib’ and ‘igāba’ (the auxiliary, ‘must’ and the noun ‘answer’, respectively) are enunciated with the hard ‘g’ that does not exist in Fuṣḥā, instead of the formal ‘yajib’ and ‘ijāba’ (with the soft j of ‘journal’).32 Subsequently, in the final scene, words related to the body (and as such of particular bearing to this chapter) including ‘jiwār’ (side, as in by your side), ‘jasad’ (body) and ‘jamīl’ (handsome) are converted to ‘giwār’, ‘gasad’ and ‘gamīl’.33

What is of interest to us here is how such a translation, completed from and in conjunction with different sources (i.e., the original novel and a theatrical adaptation of it), has brought to life a new body which sits between the original and the literally translated. In other words, al-Dimirdāsh’s creation, which runs for a total of two hours and just under sixteen minutes and maintains the plot and spirit of Jane Eyre, even though it is incomplete in so far as it is not a verbatim translation of the novel, carries within its folds a high degree of relevance, which, in turn, following Derrida, ‘carries in its body an ongoing process of translation […] as a translative body’.34 This ‘translative body’ is also what ‘[leaves] the other body intact but not without causing the other to appear’, meaning that it is progressively moving and is always viewed apropos the originals and other translations at the same time.35 Expanding the remit of Derrida’s analysis, I posit that this somatic outlook of a ‘relevant translation’ places the original and the translation in close (physical) proximity to each other, as two or more corpora whose materialities are continually shared.36 Indeed, it is notable that al-Dimirdāsh’s script for radio itself became the foundation for multiple theatre productions, each one a minor adaptation of the ‘relevant’ text.

While the general aim of the serialised radio broadcast (as announced orally by the narrator at the beginning of the broadcast and subsequently in writing when it was adapted in turn to the stage) was ‘to transmit some of the wonders of world literature in Arabic’,37 other aims may come to the fore when the medium itself is scrutinized. For example, radio broadcasting in Egypt during that particular time was on a par with the unmatched role of Egyptian cinema both worldwide and in the Arab region. That said, translating this quintessentially English text, not only into Arabic but into Arabic voices and sounds,38 simultaneously built an ever-expanding audience but equally centralised orality in Arabic as a vital medium for such translations, narrating a story whose ethical and social specifics are distinct from the language to which it is translated.39 This, as highlighted by the adaptation’s reception, has offered an engagement and a subsequent debate that are triggered, strictly speaking, by the fluid nature of the broadcast and its translation, inviting people to listen to an Arabic (or a version of Arabic) that is set against or in conjunction with other Egyptian dramatisations in the Arabic language.

What appeared to be at stake in translating and broadcasting Jane Eyre on the national Egyptian radio is how, in privileging listening to a story, the narrative itself is consumed by the voices enacting the novel and their traces of Egyptian vernacular. Notably, in a medium that requires listening, rather than reading a novel whose narrative includes key speech-like elements, the line for which this novel is widely known in English — ‘Reader, I married him’ — is poignantly missing. Instead, the radio broadcast concludes with Jane answering Mr Rochester’s question ‘Will you marry me?’ through the passionately enunciated responses ‘bi kulli surūr’ (with pleasure) and ‘bi muntahā ar-riḍā’ (with full acceptance) (circa min. 2h13). In a closing scene consumed with heavy breathing and eroticism, the broadcast ends with Mr Rochester asking Jane to kiss him, followed by dramatic music reaching a crescendo.

While the line is absent in al-Dimirdāsh’s adaptation, Munīr al-Baʿalbakī’s Arabic 1985 translation of the novel (discussed in more detail below) beautifully captures the agency which belongs to ‘I married…’, by omitting the first person subject pronoun anā in order to rely only on the implied subject in the verb conjugation, thereby maintaining the emphasis on the verb/verbal sentence and, importantly, centralising Jane as the woman who ‘actively married him’:40 wa tazawajtu minhu, ayyuhā al-qāriʾ,41 which, back translated into English would be: ‘And I married (from) him, O Reader.’

In spite of sacrificing one of the novel’s defining lines (‘Reader, I married him’) by privileging listening, rather than reading, the radio adaptation inadvertently introduces the audience to a translation that is only recognisable as a translation through its inclusion of English names and sites, and more importantly through the foreignness of such names contra what is considered local and non-foreign by the listener. As the broadcast itself focuses on the audible and not the written, as explained by al-Dimirdāsh in his introduction to the adaption, the written only appears schematically in adverts for the programme in the form of an introductory list comprising: the title of the original work and its author in English, the sources, the radio station, the translator/director’s name and the main cast. As this is still a translation, albeit incomplete, of Jane Eyre — one that has ushered in further and more textually complete versions — in this sense, this translation can be regarded as ‘prismatic’: ‘one which is alert to translation’s proliferative energies’, contra the solely reproductive modes that engender sameness in translation, as theorised by Reynolds.42 If they were to be pinpointed, these ‘proliferative energies’ in al-Dimirdāsh’s version would be the afterlives of his translation; its role was to propel the texts involved to new lives of their own, not only in connection to one another but also independent of one another. When al-Dimirdāsh offered the listener the opportunity to listen to and learn from this version, he did so by creating an enacted narrative performed by Egyptians to be received through radio broadcast across Egypt and beyond.

In all, it is not an exaggeration to maintain that al-Dimirdāsh’s 1965 version has contributed immeasurably to Jane Eyre’s reception in Arabic; first, by recentring orality in the Arabic tradition as a medium whereby new knowledge is transmitted and contested,43 this time in translation, and secondly, in crafting a scripted version in which difference is inherent to every subsequent performance of the script, which travelled across media from the radio to theatre, in a process of intersemiotic translation. In brief, this version is in itself multiple versions of Jane Eyre, both in translation and in reception.

Jane Eyre’s Corpora: ḥikāya or qiṣṣa?

Following this introduction to al-Dimirdāsh’s adaptation and serialisation of this prismatic body, focusing on orality and translational fluidity in radio, in this section I explore how these issues continue into printed translations of the novel into Arabic. In particular, my discussion of al-Dimirdāsh paves the way for an interrogation, firstly, of how translators have engaged with Jane Eyre’s genres, and subsequently how the name Jane Eyre is inscribed and pronounced in its Arabic translations.

With reference to the genres invoked by the novel’s translators, as I set out below, in Arabic the question of storytelling falls under two complementary, albeit technically different, spheres: the ḥikāya and the qiṣṣa, which, in turn, convey varied hierarchical schemata with regards to the orality and the indefiniteness of the former (as also explained in relation to al-Dimirdāsh’s 1965 adaptation) and the solidity and the testimonial nature of the latter.44 In this section, I shed light on the translators’ labelling of Jane Eyre variously as a ḥikāya (a tale transmitted orally, and attributed to orality and fluidity in the Arabic tradition), qiṣṣa (a story, intimately related to the fixed/written and the Qur’an45) and/or riwāya (the contemporary novel).46 In particular, I focus on al-Baʿalbakī’s 1985 translation, given the particular pertinence of this text on multiple levels. Indeed, contra Derrida’s assertion that translations carry and maintain ‘a debt-laden memory of the singular body’,47 in Arabic, al-Baʿalbakī’s translation has in a sense taken over from the English text and as such, the most recent translations still rely heavily and at times ‘adopt’ and ‘adapt’ sections from al-Baʿalbakī’s.48 It is very likely that the legacy of this translator’s family — the owners and founders of the authoritative Al-Mawrid English-Arabic Dictionary series and the publishing house Dār Al- ʿIlm Lil-Malāyīn — significantly contributed to the centrality and popularity of this translation.49

What is particularly notable in the original introduction to his 1985 translation is that, rather than characterising his translation as embodying one specific genre, al-Baʿalbakī refers to Jane Eyre interchangeably as a ḥikāya, qiṣṣa, and/or riwāya.50 Importantly, the use of such overlapping labels is not specific to translations alone, as we can also see in the classical case of the Arabian Nights (also One Thousand and One Nights, Alf Layla wa-Layla)51 — a text that was itself read by the eponymous heroine as a child and through which Jane Eyre has often been analysed52 — which has been referred to in Arabic simultaneously as ḥikāya (pl. ḥikāyāt) and qiṣṣa (pl. qaṣaṣ). In defining the Arabian Nights as ḥikāyāt, the stories are situated within traditions of orality and oral story-telling (whereby each retelling leads to new versions of the story itself), while the term qiṣṣa invokes the salience of the written, recognising the Arabian Nights as semi-complete, semi-textual tales.53

In Arabic, qiṣṣa (Q–Ṣ–Ṣ) (pl. qaṣaṣ) refers to ‘that which is written’54 and as such that which is demarcated by a fixity that prevents the reader (hence the interpreter) from tampering with it, thus accepting it as a complete version which is in no need of any addition or subtraction. Given its intimate linkage with the stories narrated in the Qur’an — such stories are called qaṣaṣ in the Qur’an, always in the plural — the qiṣṣa carries connotations of holiness and definiteness such that its borders are rarely violated. For instance, Sūrat Joseph (Chapter Yousif) reads: ‘We tell you [Prophet] the best of stories [aḥsan al-qaṣaṣ] in revealing this Qur’an to you’ (11:118–12:4).55 In these Qur’anic chapters, stories of past prophets and messengers; their wives and other significant women; elders; animals and insects are recounted for the listener (before the reader, given that the Qur’an was transmitted orally before being transcribed) so that lessons can be gleaned from these parables.

As stories reported in the Qur’an are considered to be undeviating texts, their fixity is not only attributed to the divine; that is, the narrative that is owned by and referred to God in all its predetermined facets and specifics, but it is also attributed to the authority that dominates (in) as well as guards the parameters of the storyline, in this case the author and the original language of the text under study. When the narratorial fixity of the qiṣṣa becomes a literary itinerary towards all things in the text, be they real, imagined, sacred, truthful (to an extent) and/or allegorical, its status becomes that of a witness statement insofar as the act of reporting or bearing witness takes place through the eyes of an authority figure who is supposed to be all-knowing, or at least who knows better.56

Such an attribute, still within the Arabic canon, can be easily contradicted, on the other hand, by the ability of the ḥikāya — (Ḥ–K–Y), ‘a speech like a story’57 — to transcend its text and in turn refuse to adhere to a discursive linearity which is simply that of a tale. Since it is the narrative or the storyline that the ḥikāya is transmitting in multiple forms, this transmission becomes less of a text and more of an ongoing narrative, which is based on a direct relationship between an author or a narrator and an audience (notably echoing Jane Eyre’s narrative style in English). In this sense, the ḥikāya represents the collective, which is normally maintained as multiple versions of itself through a continual series of narrations, in direct contrast to the qiṣṣa whose own survival is solely contingent on the specificity within the text, which is supposed to be passed on as it is.58 Such a direct variance between the qiṣṣa, on the one hand, and the ḥikāya, on the other, takes us to the question of orality and its centrality in the latter, as explained earlier with reference to al-Dimirdāsh’s adaptation of Jane Eyre. This orality, which can be likened to a nerve that goes through the ḥikāya’s entire body, counters the qiṣṣa, whose wholeness is guarded across time and space in the form of a text (even if it originated in the oral transmission that was subsequently written down). As the integrity of the ḥikāya is not contingent on the specific but on the collective instead, the multiple, the progressive and the tendency to evolve in terms of length and popularity are more palpable.

Such a distinction becomes increasingly critical when ‘stories’ such as Jane Eyre are translated into Arabic, and when the corpus of Jane Eyre is itself labelled by the translators variously as not only a riwāya (novel) but also simultaneously as a qiṣṣa or ḥikāya, as is the case with al-Baʿalbakī’s translation. While acknowledging that Jane Eyre is indeed technically both a riwāya (novel) and a qiṣṣa (story), and noting that these are at times used to refer to the genre that the text belongs to rather than to name the tale itself, the term ḥikāya is also used — as a descriptor of the story — throughout the prefaces and introductions of selected translations of Jane Eyre, including those by al-Dimirdāsh, al-Baʿalbakī, Rāghib and Ṣabrī Al-Faḍl.59 Such invocations, I would posit, are not circumstantial, but a clear indication of the way in which translation has been conceived of — in other words, the fluidity that is attributed to ḥikāya (a story that changes in its retelling) contra the fixity of the text-based qiṣṣa, which in turn resonates with Derrida’s abovementioned reflections on the tension between translation-as-staying-the-same and translation-as-change. The latter is of particular relevance given the employment of qiṣṣa in the Qur’an and the particular approach to translation that has historically been applied in translations of the holy text: far from ascertaining that the Qur’an is untranslatable per se, its translations are generally viewed as a means of capturing the meaning (maʿnā) of the text, rather than translating the text itself.60

I would thus argue that the abovementioned translators’ references to Jane Eyre as a ḥikāya — a choice that I would argue may have been facilitated by the first-person narrative with its speech-like elements in the novel — can be interpreted as a desire not to depict translation as a production of one equivalent of the origin, but rather as a creation of a version that is susceptible to other versions and interpretations. For instance, in line with the fluidity of story-telling, al-Baʿalbakī’s willingness (among other translators) to shift at times from the static to the fluid is worth noting. Tying back to the question of translating religious texts, al-Baʿalbakī handled the numerous references to the Bible and the Old Testament in Jane Eyre not only by including verbatim extracts from existing Arabic versions of the Bible, but also — given that many of the translation’s readers would be Muslim — by adding explanatory footnotes throughout to explain the significance of key Christian personae. In turn, al-Baʿalbakī adopted fluid means when facing the challenge of translating a text replete with references to the soul and the spirit, as these relate to Christian doctrine. On the one hand, he adopts the term rūḥ (pl. arwāḥ) throughout the text to refer to both ‘soul’ and ‘spirit’, as noted in Table 1; in spite of theologically-charged debates pertaining to Arabic and Islamic approaches to the meanings and translation of the terms ‘soul’ and ‘spirit’,61 this approach could be viewed as reflecting what Abdulaziz Daftari refers to as the ‘common perception in the Islamic tradition that there is no distinction between the soul and the spirit’.62

Table 1 Examples of ‘soul’ and ‘spirit’ being translated as ‘rūḥ’; with back translations by Y. M. Qasmiyeh.63

On the other hand, while consistently translating the term ‘spirit’ as ‘rūḥ’ throughout the novel, in a series of notable examples, al-Baʿalbakī astutely converts ‘the soul’ into individual parts of the body, through what I refer to as ‘bodily inflections’, and in so doing he renders the soul concrete in some instances:

|

Original |

|

|

‘Then her soul sat on her lips, and language flowed, from what source I cannot tell’ (Ch 8) |

ثم جرى لسانها بما تكنُّه نفسها، وتدفقت لغتها من معين لست أدري حقيقته. Back translation: ‘Then her tongue moved in synchrony with what her [inner] self [nafs] was concealing’ |

|

‘The fury of which she was incapable had been burning in my soul all day’ (Ch. 8) |

…إنّ صورة الغضب التي امتنعت هيلين عليها كانت تضطرم في جوانحي طوال النهار Back translation: ‘was burning in all my limbs [jawaaniḥ sing. janaaḥ] all day’ |

|

‘the reader knows I had wrought hard to extirpate from my soul the germs of love there detected’ (Ch. 17) |

والقارئ يعرف أني بذلت جهدا كبيرا لكي أستأصل من قلبي بذور الحب التي اكتشفتها هناك Back translation: ‘… in order [for me] to extirpate from my heart [qalb] the seeds of love…’ |

Table 2 Examples of ‘soul’ being translated through what I refer to as ‘bodily inflections’; with back translations by Y. M. Qasmiyeh.

Finally, and most powerfully perhaps, al-Baʿalbakī reclaims in translation the position of Palestine in rendering the second part of the English line ‘I saw beyond its wild waters a shore, sweet as the hills of Beulah’ (Chapter 15) as ‘jamīlan ka hiḍāb Filastīn’ (‘as beautiful as the hills of Palestine’).64 Such a retelling is poignant since it enables the novel to be situated not only in the Arabic language but also within Arab readers’ cultural and historical frameworks, and both geographical and imaginary landscapes.

In these ways, al-Baʿalbakī’s multiple categorisations of Jane Eyre as not only a riwāya (novel) and qiṣṣa (story) but also a ḥikāya demonstrate the fluidity that characterises the retelling of Jane Eyre in translation, a fluidity inherent within the materiality of story-telling and its capacity to articulate (or perhaps ‘domesticate’) a foreign text in a popular way and to a wider audience. Indeed, this approach to the textual (corpus) as materiality can be viewed as being closely linked to ‘conversion’, in line with Derrida’s conceptualisation. In this vein, the materiality of the text is connected to the materiality of the translator’s voice and location, with the translation of Beulah as Palestine being an instance of how, far from being fixed, the source’s signifieds can undergo transformation as they pass into another body and location.

As I argue in the remainder of this chapter, to translate a story into another story, it is important to examine the body of the story in the target language in order to see whether all of the elements — including, in particular, literality, sounds and names — are consciously preserved as they are (however impossible this might ultimately be) or whether, in particular, the narratives are privileged at the expense of other features. It is to this question that I now turn, firstly with reference to the different written and voiced iterations of the name Jane Eyre, and, subsequently, to touching as a means of calling out the mutable nature of the body in translation.

Naming and Titling in Jane Eyre

In ‘Des tours de Babel’, Derrida poses the question: ‘“Babel”: first a proper name, granted. But when we say “Babel” today, do we know what we are naming? Do we know whom?’65 Echoing this question, how can proper nouns that belong to one language66 — to spaces demarcated by the particularities of sounds, inflections and enunciations — be translated into another language? In this section on translating the name, I begin with the notion of the proper noun and the title in the Arabic tradition while assembling some of the many ‘Jane Eyres’ that have appeared in Arabic thus far. In so doing, I seek to trace the ways that the name itself engenders new names, identifying the writing and pronunciation of the proper name as a particular instance of the materiality and fluidity of the text.

Building on the extent to which the word ‘title’ in Arabic — according to the encyclopaedic Lisān Al-ʿArab, for instance — is understood as the ‘container’ of the text (from the first to the final word), I would argue that such a conceptualisation makes the title the protector of the beginning and the end of a given text, and everything in between. In other words, the title, alongside its different interpretations, is the only element within a text that is capable of delimiting the text itself.67 In Arabic, the verb ʿanan — that is, ‘to bestow a title on something’ — is also understood as follows: ‘to be or to appear in front of something or somebody’ and/or ‘to block the line of vision’. In turn, the noun ʿunwān (title)68 is the trait of the book and also the sign or the trace that appears (gradually) on a person’s forehead as a result of excessive prostration;69 this trace, in turn, is perceived to be a sign of total submission to God and a reiteration of piety. As such, through the title Jane Eyre (whose full original title in English is Jane Eyre: An Autobiography) or its translations alone we can identify a direct correspondence between two corpuses, or more than two: the English, the Arabic and the multiple transliteration(s) of specific sounds from English into Arabic. With reference to the latter, although transliteration belongs to and is managed by Arabic on the basis of the Arabic alphabet, the sounds themselves and their combinations therein are quasi-shared between English and Arabic, a dynamic I explore in more detail below.

In two of the Arabic translations consulted for the purposes of this chapter,70 the name ‘Jane Eyre’ in the title of the book has been either preceded or followed by ‘Story of’ or ‘Story of An Orphan’, making the Arabic title ‘Story of Jane Eyre’ (Qiṣṣat Jane Eyre) or ‘Jane Eyre or Story of an Orphan’ (Jane Eyre aw Qiṣṣat Yatīma) respectively.71 While the addition of ‘an orphan’ within the title marks out these Arabic titles from other languages, given that ‘orphan’ has been incorporated into the formal title rather than being presented as a subtitle,72 in some sense this retitling process echoes translations into other languages, whereby the original English subtitle (‘An Autobiography’) was replaced by references to ‘the orphan’ or ‘a governess’ (following the 1849 publication of Jane Eyre ou Mémoires d’une gouvernante/Jane Eyre or Memoirs of a Governess, and Charlotte Birch-Pfeiffer’s 1853 stage version Die Waise von Lowood, the Orphan of Lowood). The inclusion of the term ‘orphan’ within the title is paralleled by the exclusion of the original subtitle: even though some of the reviews of the Arabic translations, as well as some of the bilingual (normally abridged) translations published by Dar Al-Bihar in Syria (with no named individual translators), have used words such as ‘autobiography’ and/or ‘autobiographical’ to describe the novel and therefore situate it in a wider genre, the translators themselves have never done so in any of the texts consulted. Of particular relevance in light of my discussion of the multiple labels used by translators themselves to describe the genre (variously as qiṣṣa, ḥikāya or riwāya), is that the Arabic retitling in these two instances is relatively unique, writ large, precisely due to the insertion of ‘story’ into the title itself (with notable exceptions being two recent translations in the Thai language73). Importantly, the prominence of qiṣṣa on the covers of these translations is nonetheless often complemented, as discussed above, by the translators situating the text within the framework of the ḥikāya.

Whether with or without subtitles, and the above-mentioned additions and exclusions, we can argue that we bestow a proper noun/name on the text mainly to view everything through the eyes of the named. In this context, for example, the name is itself the title, and vice versa. To take it (back) to Arabic and to find an equivalence, we resort to multiple transliterations of the name or names (Jane Eyre) to substitute another name or names. But should names always be perceived as transferable, interpretable and translatable as names? What if, for example, this vocal directness — that is, the preservation of the name as it is, with its unique pronunciation which only belongs to itself — cannot be sustained in other languages, as is the case in Arabic? Would such a transfer convey the same name, or could we simply assume that all names are pseudonyms in translation? Such questions push against Derrida’s argument in ‘Des tours de Babel’ and expand the focus developed in ‘What is a relevant translation?’ in so far as Derrida, in those essays, does not acknowledge the importance of the traces of vocality — the implied pronunciations — that are inscribed in writing; it is by emphasizing their significance that I therefore seek to move on from Derrida’s work.

To ponder the untranslatability of the proper noun, Jane Eyre, from English into Arabic, it is worth examining the title’s two constituent parts: Jane and Eyre. As demonstrated in Table 3, which lists the transliterations of the title alongside the translators’ names and years of publication, in the Arabic translation, Ja (in Jane) = J+a and Ey (in Eyre) = E+y have been matched with either J جا or Jī جي or Ā آ or Ī إي respectively, as a result of the absence in Arabic of direct equivalents of the elongated and wide sound combinations that exist in English. Such appropriations and/or distortions, in the form of alternative Arabic pronunciations to the original, open the title up to different readings that, in turn, engender new titles/translations, which act independently of the original title itself.74 Notably, Derrida does not discuss pronunciation in ‘Des tours de Babel’ and as such in this discussion I build and expand upon his approach, with my analysis aligned to this volume’s emphasis on the prismatic nature of translation, as I argue that the very reiteration of a proper name through language difference has a prismatic effect.

The way that Jane has been transliterated is closely aligned with the word jinn (spirit or genie), in particular when the diacritics (signs written above and below the letter to mark its corresponding short vowel sound) on the word jinn are not visible.75 Of particular relevance to the focus of this chapter on the body, the word jinn is itself derived from the root J–N–N which refers to concealment and the lack of physical presence. In turn, the equivalent of Eyre, when commonly transliterated into Arabic, ties to another aspect of the body: that is, ʾayr, which is the penis.76 This may be one reason why the titles of the book rarely bear diacritics — even though such signs would make the transliteration more accurate sound-wise — as these signs would more concretely pin down the pronunciation of the name and tie it to such connotations. At the same time, we can assume that the general absenting of the glottal stop in the transliteration of Eyre (ʾayr) may have purposely been applied in order to move the transliteration away from its close Arabic homophone.

Standing out from the other transliterations is al-Baʿalbakī’s rendition of the title, both in its usage of diacritics in the 1985 version, and its unique approach to transliterating the surname: إيير (al-Baʿalbakī’s choice) and آيير (used posthumously, and we can assume amended by the publishing house). As per Table 4 below, the sound choices here are difficult to recapture closely in English — the first broadly corresponds to an elongated ‘ee’ (‘eeer’) and the second to ‘aayir’. Importantly, each and every reader, especially those unfamiliar with the pronunciation of the English title, would imagine and enunciate these nominal alternatives differently.

Table 3 Some of the Arabic ‘Jane Eyres’ compiled from different translations completed between 1965 and 2017.

|

Guiding Sounds and Letters |

Transliteration |

|

ج |

‘j’ |

|

جْ |

‘muted j’ |

|

جَ جا |

‘ja jā’ |

|

جُ جو |

‘ju jū’ |

|

جِ جي |

‘ji jī’ |

|

ا |

‘elidable hamza’ |

|

أْ |

‘muted a’ |

|

أَ آ |

‘short and long a’ |

|

أُ أو |

‘short and long u’ |

|

إِ إي |

‘short and long i’ |

|

ن |

‘n’ |

|

ي |

‘the consonant y or as a long vowel ī’ |

Table 4 Guiding sounds and letters with their transliterations in the Arabic transliterations of the name ‘Jane Eyre’.

As it is the name that we are carrying from one language to another, not as the same name, but as a metaphor of a name, it becomes clear in Arabic that the ‘foreign’ (aʿjamī) (that which has no equivalence in Arabic) becomes ‘more foreign’ in translation by being moved away from its autochthonous sounds. To draw the name-metaphor apposition closer, the words kunya and kinya (كُنية or كِنية) in Arabic (epithet, title, name, surname, nickname) are etymologically related to the word kināya (كِناية) (metonymy, metaphor, sign, symbol). Such an affinity is relevant in this context in the interpretation of the translation of names as a production of ‘new’ metaphors and/or signs that will eventually take over from the name, as is the case in the Arabic titles. Indeed, such processes arise throughout Arabic translations of novels bearing ‘foreign’ proper nouns, and yet perhaps have especial salience in the case of Jane Eyre because of the challenge of the repeated vowel sounds and also because of the suggestiveness of the name in the novel.

Despite the fact that these Arabic transliterations belong to or are derived from the English Jane Eyre, I would argue that they equally sit outside the text as written and, as such, they become extra-textual within the origin. This extra-textuality being established in the Arabic text may be seen as a third text:77 it is neither English (entirely) nor Arabic (entirely) but a combination of both, whose main aim is to produce an equivalent that resembles the English Jane Eyre as best as Arabic sounds can do. Importantly, since it is the female name that is engendering all these names, it becomes apparent how some Arabic translators, when transliterating the name Brontë, at times opted to use the feminine marker (al-tāʾ al-marbūṭa) (Bruntah) and not an elongated ee (Bruntee) (which is more common) in order to make the feminine more physically present through the suffix.

In the absence of capital letters in Arabic to mark the proper nouns, most Arabic translations have relied on brackets to declare and concretise the names of people, places, titles and languages throughout the novel. In so doing, they have reinforced physical borders (to borrow Reynolds’s words78 in another context) around the proper nouns for the sake of foreclosing any other assumptions beyond the proper noun and the title. Such an approach in the Arabic translations has transformed the name itself into a border, firstly, in its potentiality to (re)assert as well as delineate the linguistic ‘difference’ between Arabic and English, and secondly, in positing the name’s life as that which transcends the life of the translation itself.

‘Touching’ Jane Eyre

Rather than seeing translating as lifting above materiality and then mourning it (as argued by Derrida), I have shown that translation does not rise above, but moves through materiality, thereby not only generating change but also, in so doing, producing a questioning textuality in which translation is more like touching than like transfer, with the concomitant question arising: how much can a touch accurately apprehend? Building on the preceding analyses, in this final section, I discuss touch in more detail, arguing that the Arabic is not only different from the English, but is also arguably more nuanced: in a sense, it apprehends more than the English knows. I thus examine the multiplicity (and inherently metaphoric nature) of the Arabic translations of the verb ‘to touch’ in Jane Eyre, thereby elucidating how ‘touching’ is rendered in Arabic and in what ways its translation goes beyond the English, not with the aim of identifying similarities across the languages, but to engender prismatic readings in both the English and its Arabic equivalent. To develop this text-based reading of the translation of ‘touching’ in Jane Eyre, I continue referring to Munīr al-Baʿalbakī’s 1985 Arabic translation of the novel, which, as noted above, is still considered to be the most reliable of the Arabic literary translations, to the extent of being elevated to the status of a quasi-source text. In this translation, three key Arabic verbs are used to refer to ‘touching’: massa, lamasa and lāmasa.

In Sūrat Maryam (Chapter Mary) in the Qur’an, Maryam asks: ‘How can I have a son while no man has touched me and I have not been unchaste?’79 The Arabic verb used in this verse to convey ‘touching’ is massa (from the Classical Arabic root M-S-S) which connotes the most delicate of touches, which can only be captured or sensed if the touched person is fully in tune with an emanating touch. Since the overriding aim of this Qur’anic verse is to dispel the possibility of conceiving through touching (Maryam is supposed to be a virgin), the verb massa is employed as an alibi for no perceptible touch. The other verb that is used in Arabic to convey touching is lamasa (L–M–S), which is attributed to the hand touching another part of the body, thereby highlighting precisely the corporeal aspect of, and in, touching. The third verb, which is in fact a variant of the second, is lāmasa (L–M–S); unlike lamasa, lāmasa (with an elongated first ā sound) is interactive and connotes interchangeable movements. This thereby makes both parties (the toucher and the touched) equally involved in the process of touching.

In the following examples — quoted from the original (English) version of the text — I start from the premise that al-Baʿalbakī’s treatment of the act of touching in his translation of Jane Eyre embodies interpretations (and/or versions of translations) that occur first within Arabic, before being perceived as equivalences, alternatives and/or substitutes for the English.

With the word ‘touch’ absent from the first phase of the novel at Gateshead, where physical contact is primarily aggressive, it is only when the as yet unnamed Miss Temple encounters ‘Jane Eyre’ that touch becomes an important motif in the novel, bringing the name, the body and touch together: ‘“Is there a little girl called Jane Eyre, here?” she asked. I answered “Yes,” and was then lifted out.’80 The initial bodily encounter — being ‘lifted out’ or, returning to Derrida, perhaps ‘relevée’ — not only arises a few short paragraphs after a noteworthy instance of the whole name ‘Jane Eyre’ (rather than solely the first name, Jane) being enunciated, but is followed by an unusually gentle touch for Jane to experience:

She inquired how long they had been dead; then how old I was, what was my name, whether I could read, write, and sew a little: then she touched my cheek gently with her forefinger…

In his translation of this sentence (p. 68), al-Baʿalbakī acknowledges the gentleness of the touch as reiterated in the original by opting to use the verb massa (transliterated as ‘thumma massat wajnatayy bi subbabatihā massan rafīqan’, literally, ‘then she touched my cheek with her forefinger a delicate touching’).81 In doing so, the touch(ing) becomes a marker of a beginning, in other words, a gentle initiation — as interpreted in Arabic — that is performed in/on/through body parts that are considered less intrusive and therefore less physical than others.

In the second instance of physical touching in the novel, which comes immediately after the first, when Jane is new at Lowood and is determining how to connect to the place and the people there, massa again (and not lamasa) is used in the Arabic version:

When it came to my turn, I drank, for I was thirsty, but did not touch the food.82

It would not be entirely unusual to use the verb lamasa in this context, precisely because this verb is used to convey the process of palpably touching food. However, al-Baʿalbakī invokes the verb massa to reflect the nature of the rejection of the food: it is an outright rejection, a rejection even of the intention of touching. In this way, the Arabic verbs — massa versus lamasa — are placed in a hierarchy according to subtle proximities and, through these nuances, the involved subjects are separated or united. In other words, translating touching in Arabic seems to touch first and foremost on multiple degrees of touching inherent in the language itself.

In turn, the third (and last) example of touching in Lowood pertains to Helen — ‘but I think her occupation touched a chord of sympathy somewhere; for I too liked reading’ — and once again the verb massa is used by the translator, indicating the subtlety and profundity of such touching.83

Contra the consistent usage of massa in Lowood, the first touches that occur after Lowood arise from the earlier encounter with Rochester and his horse, and move us away from this first ‘touching’ verb. The original version in English reads ‘I should have been afraid to touch a horse when alone, but when told to do it, I was disposed to obey’, followed by ‘A touch of a spurred heel made his horse first start and rear, and then bound away.’84 In both of these instances, the translation of ‘touch’ through the verbal noun lams and then lamasa, embodies the greater physicality that is taking place, and the active and direct process of touching by the subjects (pages 187 and 188): the latter is demonstrated clearly in the back-translation of the second line: ‘and he touched his horse with his heel (the one) which has spurs…’.85

In contrast, al-Baʿalbakī chooses to use the verb lāmasa (with an elongated ā) to exemplify the outward and interactive nature of the process, as clearly illustrated in the following quotation from the English, which once again brings together touch and an enquiry about a name:

Just then it seemed my chamber-door was touched; as if fingers had swept the panels in groping a way along the dark gallery outside. I said, ‘Who is there?’86

In the Arabic translation, the first touch is converted into the active voice (‘And at that moment it seemed to me as though a thing had touched the door of my room’), using the verb massa to allude to the fact that this touch has originated from an unidentifiable source, whereas the verb ‘swept’ is translated with lāmasa, as if the fingers and the panels are rubbing against one another.87 Amongst other things, opting to use lāmasa for ‘swept’ highlights the multiple levels of touching taking place within the same context.

As a final cluster of examples,88 included here in the English, touch re-emerges powerfully in the penultimate chapter, when Jane goes to Mr Rochester at Ferndean.

He put out his hand with a quick gesture, but not seeing where I stood, he did not touch me.

“And where is the speaker? Is it only a voice? Oh! I cannot see, but I must feel, or my heart will stop and my brain burst. Whatever — whoever you are — be perceptible to the touch or I cannot live!”

“You touch me, sir — you hold me, and fast enough: I am not cold like a corpse, nor vacant like air, am I?”

In these examples from Chapter 37, the verbs massa and lamasa are both used in various forms. The first verb ‘touch’ is rendered massa. ‘[H]e did not touch me’ is translated as ‘lamm yasammanī’ (sic) — ‘lamm yamassanī’ which invokes a touching that did not actually happen, hence the use of a form of touching that is too discreet in massa instead of the physicality inherent in lamasa.89 As a brief aside, and prompted by the typographical error included on page 701, where yamassanī is incorrectly written as yasammanī by inverting the order of the s and the m, the verbs massa (to touch) and sammā (to name) that are conflated here draw powerful attention to the very connection that is at the heart of this chapter on the relationship between the body and the name.

In the following two lines included above, ‘I feel’ is rendered ‘I touch’ (almis, from lamasa) in line with the English ‘to palpate’, which in this case mainly refers to the movement of the body towards another body, with the intention of physically reaching out; in turn, ‘perceptible to touching’ is translated through the verbal noun of lamasa, lams, thereby once again highlighting the physical attribute of this type of touching.90 Finally, exemplifying the actual act of touching taking place, ‘You touch me, sir’ is translated by al-Baʿalbakī as ‘anta talmisunī ya sayyidī’: ‘You are touching me, sir’.91 With no doubt, the urgency and definiteness of this touching rebuts any suggestion that Jane Eyre could be ‘cold like a corpse’ or ‘vacant like air’.

Since touching does not solely involve one specific body part, as Derrida contends,92 or more precisely as it escapes the local or localised in other senses, one might argue that this multidirectional touching retains the inherent prisms in language. In this sense, these multiple and yet particular readings of touching in Jane Eyre and al-Baʿalbakī’s Arabic translation of this important novel cannot but usher in a constant return to both languages, not to limit meaning in any way, but rather to open more possibilities within and beyond both texts.

Conclusion

In this chapter I have sought to build upon, and in so doing move on from, Derrida’s pivotal article, ‘What Is a “Relevant” Translation?’, advocating for the development of a more nuanced, and indeed prismatic, approach to translation and embodiment, one that conceives of translation as a touching of bodies rather than a (guilt-ridden) rising above them. Throughout, I have complicated the distinction between speech and writing, and highlighted the pluralistic relationships between the body and translation, arguing that the Arabic translation is not merely ‘different’ but at times apprehends more than the English knows. In the scene that draws both this chapter, and Jane Eyre itself, to a close, the relationship between speech and touch is (to return to Derrida) particularly ‘relevant’. As Mr Rochester has become blind and can no longer read, Jane instead reads to him out loud, thereby undertaking a particular form of translation — from the text to the oral and the aural — which resonates with al-Dimirdāsh’s 1965 adaptation of the novel: from the text, to the script that is performed by the actors on radio and subsequently consumed by the listener. While al-Dimirdāsh’s adaptation is subsequently reborn as a play, to be observed as well as heard, Jane Eyre’s reading out loud (or storytelling) to Mr Rochester takes precedence over sight, pushing sound to the forefront while relegating sight to the background: ‘never did I weary of … impressing by sound on his ear what light could no longer stamp on his eye.’ At the same time as sound becomes a form of touch, and as emotional and physical sensing and feeling come together as one, so too does touch itself appear as a dynamic that is not only felt but is also a new language (literally) that gathers two corpuses afresh within its folds: Jane’s and Mr Rochester’s.93

The relationship between translation and the body is further concretised in al-Baʿalbakī’s retelling of this scene, since, in the Arabic translation, both ‘impressing’ and ‘stamp’ are rendered with the same verb, ṭabaʿa, which, importantly, mean ‘to print’ and ‘to inscribe’, as though to remind the reader that senses are always in translation — so to speak — and can therefore be expressed differently.94 While ṭabaʿa refers, inter alia, to the written, this closing account demonstrates the interconnectedness between the multiple senses of translation, and the processes of conversion, both bodily and textual, that take place throughout. The retelling of Jane Eyre that takes places through translation highlights the ways that languages and genres alike are converted, including through the labelling of Jane Eyre as both ḥikāya and qiṣṣa, and the fluidity that exists between and through the oral and the written. Creating versions that are susceptible to other versions in this case is also intimately linked to the complexity of translating the name, including in the very title of the novel under analysis. In light of the variable, and suggestive, sounds of the name in Arabic, the not-one Jane Eyre captured in transliterations of the proper noun engenders different versions of the novel, as the Arabic Jane Eyres will always be subject to readers’ differing interpretations and voicings; readings and translations that are, at their very core, inherently prismatic.

Works Cited

For the translations of Jane Eyre referred to, please see the List of Translations at the end of this book.

Abdel Haleem, M. A. S., The Qur’an: Parallel Arabic Text, trans. By M. A. S. Abdel Haleem (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000).

Al-ʿAdawī, Muḥammad Qiṭṭa, ed., Alf Layla wa-Layla (One Thousand and One Nights) (Beirut: Dār ṣādir Lil ṭibāʿa wa al-Nashr, 1999).

Batchelor, Kathryn, ‘Re-reading Jacques Derrida’s ‘Qu’est-ce qu’une traduction “relevante”?’ (What is a ‘relevant’ translation?), The Translator (2021), 1–16.

Bennington, George and Derrida, Jacques, Jacques Derrida (Chicago: Chicago University Press, 1999).

Bhabha, Homi K., ‘Cultural Diversity and Cultural Differences’ in The Post-Colonial Studies Reader, ed. by Bill Ashcroft, Gareth Griffiths and Helen Tiffin, 2nd edition (London: Routledge, 2006), pp. 155–57.

Brown Tkacz, Catherine, ‘The Bible in Jane Eyre’, Christianity and Literature, 44.1 (1994), 3–27.

Daftari, Abdulaziz, ‘The Dichotomy of the Soul and Spirit in Shi’a Hadith’, Journal of Shi’a Islamic Studies, 5.2 (2012), 117–29.

Derrida, Jacques, ‘Des Tours de Babel’, trans. by Joseph F. Graham, in Difference in Translation, ed. by Joseph F. Graham (Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press, 1985), pp. 165–205.

——, The Ear of the Other: Texts and Discussions with Jacques Derrida: Otobiography, Transference, Translation, English edition ed. by C. McDonald (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1988).

——, On the Name (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1995).

——, On Touching – Jean Luc Nancy, trans. by Christine Irizarry (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2005).

——, ‘Qu’est-ce qu’une traduction “relevante”?’ in Quinzièmes assises de la traduction littéraire (Arles: Actes Sud, 1998), pp. 21–48.

——, ‘What Is a “Relevant” Translation?’, trans. by Lawrence Venuti, Critical Inquiry, 27.2 (2001), 174–200.

Dickson, Melissa, Cultural Encounters with the Arabian Nights in Nineteenth-Century Britain (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2019).

——, ‘Jane Eyre’s ‘Arabian Tales’: Reading and Remembering the Arabian Nights’, Journal of Victorian Culture, 18.2 (2013), 198–212.

Druggan, Joanna and Tipton, Rebecca, ‘Translation, ethics and social responsibility’, The Translator, 23.2 (2017), 119–25.

El-Shawan Castelo-Branco, Salwa, ‘Radio and Musical Life in Egypt’, Revista de Musicología, 16. 3 (1993), 1229–1239.

Genette, Gérard, ‘Introduction to the Paratext’, New Literary History, 22.2 (1991), 261–72.

Harb, Mustafa Ali, ‘Contrastive Lexical Semantics of Biblical Soul and Qur’anic Ruħ: An Application of Intertextuality’, International Journal of Linguistics, 6.5 (2014), 64–88.

Hassan, Waïl, ‘Translator’s Note’, in Abdelfattah Kilito, Thou Shalt Not Speak My Language, trans. by Waïl S. Hassan. (Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 2008), pp. vii–xxvi.

Ibn Manẓūr, Muḥammad ibn Mukarram, Lisān al-ʿArab (The Language of the Arab People) (Cairo: Dār Ibn al-Jawzī, [1970] 2015).

Kilito, Abdelfattah, Arabs and the Art of Storytelling, trans. Mbarek Sryfi and Eric Sellin (Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 2014).

——, ‘Qiṣṣa’, in Franco Moretti (ed.) The Novel, Volume 1: History, Geography and Culture (Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press, 2006), pp. 262–68.

——, Thou Shalt Not Speak My Language, trans. by Waïl S. Hassan. (Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 2008).

Leeuwen, Richard van, The Thousand and One Nights and Twentieth-Century Fiction (Leiden: Brill, 2018).

Al-Musawi, Muhsin Jassim, The Postcolonial Arabic Novel: Debating Ambivalence (Leiden and Boston: Brill, 2003).

——, ‘The Taming of the Sultan: A Study of Scheherazade Motif in Jane Eyre’, Adab al-Rafidayn, 17 (1988), 59–81.

Nishio, Tetsuo, ‘Language nationalism and consciousness in the Arab world’, Senri Ethnological Studies, 55 (2001), 137–46.

Ouyang, Wen-Chin, ‘The Dialectic of Past and Present in Riḥlat Ibn Faṭṭūma by Najīb Maḥfūẓ’, Edebiyat: Journal of Middle Eastern Literatures, 14.1 (2003), 81–107.

——, ‘Genres, Ideologies, Genre Ideologies and Narrative Transformation’, Middle Eastern Literatures, 7.2 (2004), 125–31.

Qāsim, Maḥmūd, Al-Iqtibās: ‘Al-Maṣādir al-Ajnabiyya fī al-Sinamā al-Misriyya’ (Adaptation: Foreign Sources in Egyptian Cinema), (Cairo: Wikālat al-ṣiḥāfa al-ʿArabiyya, 2018).

Reynolds, Matthew, ‘Introduction’ in Prismatic Translation, ed. by Matthew Reynolds (Oxford: Legenda, 2019), pp. 1–19.

——, Likenesses: Translation, Illustration, Interpretation (London: Routledge, 2013).

Said, Edward, Reflections On Exile and Other Essays (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2000).

Salameh, Franck, ‘Does anyone speak Arabic?’, Middle East Quarterly, 18 (2011), 47–60.

Winter, Tim, ‘God the Speaker: The Many-Named One’, in The Routledge Companion to the Qur’an, ed. by George Archer, Maria M. Dakake, Daniel A. Madigan (New York: Routledge, 2021), pp. 45–57.

Yāsīn, Saʿīd, ‘Nūr al-Dimirdāsh.. Madrasa ikhrajiyya farīda’ (Nūr al-Dimirdāsh: A unique “school” in directing’), Al-Ittiḥād, May 2020, https://www.alittihad.ae/news/دنيا/٣٩٩١٠٦٧/نور-الدمرداش----مدرسة--إخراجية-فريدة

Zahir al-Din, M S., ‘Man in Search of His Identity: A Discussion on the Mystical Soul (Nafs) and Spirit (Ruh)’, Islamic Quarterly, 24.3(1980), 96.

Zughoul, Muhammad Raji and El-Badarien, Mohammed, ‘Diglossia in Literary Translation: Accommodation into Translation Theory’, Meta, 49.2 (2004), 447–56.

1 I am hugely indebted to Prof. Matthew Reynolds for his invaluable feedback and suggestions on different iterations of this chapter. I am also grateful to the two anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments and recommendations.

2 Matthew Reynolds, ‘Introduction’, in Prismatic Translation, ed. by Matthew Reynolds (Oxford: Legenda, 2019), pp. 1–18 (pp. 6, 9).

3 Jacques Derrida, ‘What Is a “Relevant” Translation?’, trans. by Lawrence Venuti, Critical Inquiry, 27.2 (2001), 174–200.

4 Jacques Derrida, ‘Qu’est-ce qu’une traduction “relevante”?’ in Quinzièmes assises de la traduction littéraire (Arles: Actes Sud, 1998), pp. 21–48.

5 Kathryn Batchelor, ‘Re-reading Jacques Derrida’s ‘Qu’est-ce qu’une traduction “relevante”?’ (What is a ‘relevant’ translation?)’, The Translator, (2021), 1–16 (p. 4).

6 Derrida, ‘What Is a “Relevant” Translation?’, p. 179.

7 Ibid., p. 178.

8 Batchelor, ‘Re-reading’, p. 8.

9 Ibid.

10 Derrida, ‘What Is a “Relevant” Translation?’, p. 177.

11 Ibid., p. 199.

12 Ibid., p. 178.

13 Derrida, ‘What Is a “Relevant” Translation?’, p. 179.

14 Ibid., p 199.

15 Catherine Brown Tkacz, ‘The Bible in Jane Eyre’, Christianity and Literature, 44 (1994), 3–27 (p. 3).

16 Ibid., p. 3.

17 Derrida, ‘What Is a “Relevant” Translation?’, p. 199.

18 On the position of The Arabian Nights in relation to storytelling in both Arabic and European literatures, see Wen-Chin Ouyang ‘Genres, ideologies, genre ideologies and narrative transformation’, Middle Eastern Literatures, 7.2 (2004), 125–31; Abdelfattah Kilito, Arabs and the Art of Storytelling, trans. by Mbarek Sryfi and Eric Sellin (Syracuse, N. Y.: Syracuse University Press, 2014), pp. 116–25; and Muhsin Jassim Al-Musawi, The Postcolonial Arabic Novel: Debating Ambivalence (Leiden and Boston: Brill, 2003).

19 Derrida, ‘What Is a “Relevant” Translation?’, p 199.

20 In this way, I adopt the definition of translation advocated throughout this volume (see Chapter I, by Matthew Reynolds).

21 Batchelor, ‘Re-reading’, p. 4.

22 Nūr al-Dimirdāsh, Jane Eyre (Cairo: Egyptian Radio Station, 1965). The radio adaptation is available at https://youtu.be/GF2sj8QiPfQ

23 Ismāʿīl Kāmil’s translation, published in Cairo as part of the Kitābī Series in 1956, is seen as the first translation of the novel into Arabic, and the first adaptation itself was a cinematographic one, with the first film directed by ḥusayn ḥilmī in 1961, under the title This Man, I Love. In this film, Jane Eyre’s name is transformed into ‘Ṣabrīn’, a term from the word ṣabr, meaning patience in Arabic (Maḥmūd Qāsim, Al-Iqtibās: ‘Al-Maṣādir al-Ajnabiyya fī al-Sinamā al-Misriyya’ (Adaptation: Foreign Sources in Egyptian Cinema) (Cairo: Wikālat al-Ṣiḥāfa al-ʿArabiyya, 2018), p. 1911.

24 On the popular reach of Egyptian radio during the 1960s, see Salwa El-Shawan Castelo-Branco, ‘Radio and Musical Life in Egypt’, Revista de Musicologia, 16 (1993), 1229–1239.

25 While beyond the scope of this chapter, it is worth noting the significance and particular challenges of diglossia in Arabic for translation, where the formal register and the local dialects coexist but also clash — for instance, see Muhammad Raji Zughoul and Mohammed El-Badarien, ‘Diglossia in Literary Translation: Accommodation into Translation Theory’, Meta, 49.2 (2004), 447–56.

26 Building on the present discussion of voice in the radio adaptation, in subsequent sections of this chapter I continue to dwell on the significance of voice in the written translations, in particular in relation to the multiple renderings of the name Jane Eyre. On the question of the Fuṣḥā’s purity versus the contamination of dialects see Tetsuo Nishio, ‘Language nationalism and consciousness in the Arab world’, Senri Ethnological Studies, 55 (2001), 137–46. Also see Salameh on how certain dialects are purported (by their speakers and external analysts alike) to be closer to Fuṣḥā, leading to hierarchical frames of stronger or weaker understandings of the Arabic language (Franck Salameh, ‘Does anyone speak Arabic?’, Middle East Quarterly, 18 (2011), 47–60).

27 As a brief note, I consider this adaptation to embody an attempt at conveying hybridity: first, in its reliance on both Brontë’s Jane Eyre and Helen Jerome’s Jane Eyre: A Drama in Three Acts (first performed and published in 1936) and secondly, and more importantly, in presenting this version as an attempt to introduce Jane Eyre to Arabic-speaking audiences and in so doing honouring the incompleteness that surrounds any translation.

28 For instance, he translated, adapted, and/or directed Widowers’ Houses, by George Bernard Shaw, and Richard Sheridan’s The School of Scandal for radio, the latter of which can be accessed at https://archive/org/details/P2-Dra-SchoolForScandal

29 See Said Yassin, ‘Nūr al-Dimirdāsh.. Madrasa ikhrajiyya farīda’ (Nūr al-Dimirdāsh: A unique “school” in directing’), Al-Ittihād, May 2020, https://www.alittihad.ae/news/دنيا/٣٩٩١٠٦٧/نور-الدمرداش----مدرسة--إخراجية-فريدة

30 See El-Shawan Castelo-Branco, ‘Radio and Musical Life in Egypt’.

31 Building on Zughoul and Al-Badarien, who emphasise the challenges that exist vis-a-vis diglossia and translation in Arabic and who identify the ‘phonemic substitution’ of the ‘Classical Arabic voiced palatal affricate /j/ or /dg/’ with the ‘colloquial Egyptian Arabic’ ‘voiced velar stop /g/’ as a key characteristic that enables the audience to ‘directly recognise’ the vernacularisation therein, I maintain that the radio adaption of Jane Eyre is immediately recognisable as ‘naturally dialectal’ precisely due to this vernacular substitution and inflection (see Zughoul and El-Badarien, ‘Diglossia in Literary Translation’, p. 452).

32 Al-Dimirdāsh, Jane Eyre, 17’ 20”.

33 Al-Dimirdāsh, Jane Eyre, 2’ 11”.

34 Derrida, ‘What is a “Relevant” Translation?’, p. 177.

35 Ibid., p. 175.

36 On translation and the body, see Derrida ‘What is a “Relevant” Translation?’, and also Waïl S. Hassan, ‘Translator’s Note’, in Abdelfattah Kilito, Thou Shalt Not Speak My Language, trans. by Waïl S. Hassan (Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 2008), pp. vii–xxvi (p. x).

37 Many other plays and novels were serialised in this way, including The Lady from the Sea and A Doll’s House, both by Henrik Ibsen, and available at https://youtu.be/Qbe_W8gs7Sk and https://youtu.be/-ruLNVygRyw; Doctor Faustus, by Christopher Marlowe, available at https://youtu.be/ben5H0dfhgw; and The Cherry Orchard, by Anton Chekov, available at https://youtu.be/UOVdlkoGZm0

38 Here I do not refer to sound effects (noting that the music playing in the background of the broadcast is associated with organ music for instance), but rather the specific sounds of the letters and words pronounced by the actors, who, as noted above, spoke in Fuṣḥā with vernacular (specifically Egyptian) inflections.

39 See Abdelfattah Kilito, Thou Shalt Not Speak My Language, trans. by Waïl S. Hassan (Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 2008); Joanna Druggan and Rebecca Tipton, ‘Translation, ethics and social responsibility’, The Translator, 23 (2017), 119–25.

40 In the Arabic translations more broadly, two scenarios have been offered: 1) I married him and 2) We married. As noted above, the former was captured in the 1985 translation.

41 Munīr al-Baʿalbakī, Jane Eyre (Casablanca: Al-Markaz al-Thaqāfī Al-ʿArabī/Beirut, Dār Al-ʿIlm Lil-Malāyīn, 2006), p. 727.

42 Reynolds, ‘Introduction’, pp. 2, 9.

43 See Kilito, Thou Shalt Not Speak My Language, p. 54, on the relationship between speech, transcription and rewriting; while discussing Ibn Battuta, I would posit that the broader process discussed by Kilito demonstrates the centrality of the oral as a prerequisite for writing and rewriting.

44 On genres in Arabic literature, including the very question of locating a text’s genre, see Ouyang, ‘Genres, ideologies, genre ideologies and narrative transformation’; Wen-chin Ouyang (2003) ‘The Dialectic of Past and Present in Riḥlat Ibn Faṭṭūma by Najīb Maḥfūẓ’, Edebiyat: Journal of Middle Eastern Literatures, 14.1 (2003) 81–107; Edward Said’s chapter, ‘Arabic Prose and Prose Fiction After 1948’, in Reflections On Exile and Other Essays (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2000); Al-Musawi, The Postcolonial Arabic Novel; Abdelfattah Kilito, ‘Qiṣṣa’, in Franco Moretti (ed.) The Novel, Volume 1: History, Geography and Culture (Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press, 2006), pp. 262–68.

45 Noting its inherent plurality in this tradition, it is the plural term ‘qaṣas’ that appears in the Qur’an, and never the singular noun ‘qiṣṣa’.

46 What is of particular ‘relevance’ in this regard, is not whether the text ‘actually’ belongs to one genre or another, but rather precisely the translators’ choice — which once again relays the fluidity of the process — to label the text variously as ḥikāya, qiṣṣa, and/or riwāya.

47 Derrida, ‘What is a “Relevant” Translation?’, p. 199.

48 See Nabīl Rāghib, Jane Eyre (Cairo: Gharīb Publishing House, 2007); and Amal al-Rifāʿī, Qiṣṣat Jane Eyre (Story of Jane Eyre) (Kuwait: Dār Nāshirī Lil Nashr al-Ilikitrūni, 2014).

49 Al-Baʿalbakī is considered a giant of the field, having been nicknamed the ‘sheikh of translators in the modern era’ by fellow translators, literary critics and philologists alike. The vast majority of the translations of Jane Eyre that I reviewed for the Prismatic Jane Eyre project relied extensively on al-Baʿalbakī’s 1985 translation. It is as if al-Baʿalbakī’s translation had become ‘the original of the original’ by virtue of constituting itself as a new canon within translation studies in Arabic. Eventually run by his family, al-Baʿalbakī founded, with his friend Bahīj ʿUthmān, the publishing house Dār Al- ʿIlm Lil-Malāyīn (House of Education for the Millions) which has continued to publish his English-Arabic dictionary Al-Mawrid (now in different formats: complete, concise, pocket, bilingual, middle-sized, etc.) which has exceeded its 40th edition. He translated more than a hundred books from English, including The Story of My Experiments with Truth by Mahatma Ghandi, A Tale of Two Cities by Charles Dickens, Farewell to Arms, The Old Man and the Sea and The Snows of Kilimanjaro by Ernest Hemingway, A History of Socialist Thought by G. D. Cole, The Iron Heel by Jack London, and History of the Arabs by Philip Hitti.

50 The multiple invocations of these three labels are indicative of how the Arabic translations of the text have been viewed by the translators themselves. In making this point, I do not seek to delimit the genre of the novel, but more importantly I refer to the multiple invocations of ḥikāya and qiṣṣa as a way of further developing a theory of translation.

51 Muḥammad Qiṭṭa al- ʿAdawī, ed., Alf Layla wa-Layla (One Thousand and One Nights) (Beirut: Dār Ṣādir Lil Ṭibāʿa wa al-Nashr, 1999).

52 See Melissa Dickson, ‘Jane Eyre’s ‘Arabian Tales’: Reading and Remembering the Arabian Nights’, Journal of Victorian Culture, 18.2 (2013), 198–212; on the ‘influence’ of the Arabian Nights on Charlotte Brontë and on Jane Eyre, see Muhsin J. Al-Musawi, ‘The Taming of the Sultan: A Study of Scheherazade Motif in Jane Eyre’, Adab al-Rafidayn 17 (1988), 59–81, p. 60, and Melissa Dickson, Cultural Encounters with the Arabian Nights in Nineteenth-Century Britain (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2019).

53 See Richard van Leeuwen, The Thousand and One Nights and Twentieth-Century Fiction (Leiden: Brill, 2018).

54 Muḥammad ibn Mukarram Ibn Manẓūr, Lisān al-ʿArab (The Language of the Arab People) (Cairo: Dār Ibn al-Jawzī, [1970] 2015], IV, pp. 53–57.

55 M. A. S. Abdel Haleem, The Qur’an: Parallel Arabic Text, trans. by M. A. S. Abdel Haleem (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000), p. 236.

56 On the relationship between writing and fixity in the case of the Qur’an, see Tim Winter, ‘God the Speaker: The Many-Named One’ in The Routledge Companion to the Qur’an, ed. by George Archer, Maria M. Dakake and Daniel A. Madigan (New York: Routledge, 2021), pp. 45–57 (p. 49).

57 Ibn Manẓūr, Lisān Al-ʿArab, VII, pp. 563–4.

58 Also see Abdelfattah Kilito, Arabs and the Art of Storytelling, trans. by Mbarek Sryfi and Eric Sellin (Syracuse, N.Y.: Syracuse University Press, 2014), pp. 116–25.

59 See al-Dimirdāsh, Jane Eyre; Munīr al-Baʿalbakī, Jane Eyre (Beirut: Dār Al- ʿIlm Lil-Malāyīn, 1985); al-Baʿalbakī, Jane Eyre (2006); Rāghib, Jane Eyre; and Ṣabrī Al-Faḍl, Jane Eyre (Cairo: Al-Usra Press, 2004).

60 Starting from the premise that ‘translation is both necessary and impossible’, Derrida offers the following reflection on Benjamin’s The Task of the Translator: ‘A sacred text is untranslatable, says Benjamin, precisely because the meaning and the letter cannot be dissociated’. See Jacques Derrida, The Ear of the Other: Texts and Discussions with Jacques Derrida: Otobiography, Transference, Translation, English edition ed. by C. McDonald. (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1988), p. 103.

61 On the widespread usage of the term ‘rūḥ’ and related constructs to refer both to the soul and to the spirit in Arabic, see Mustafa Ali Harb, ‘Contra stive Lexical Semantics of Biblical Soul and Qur’anic Ruħ: An Application of Intertextuality’, International journal of Linguistics, 6.5 (2014), 64–88. It is beyond the scope of this chapter to discuss the theologically-charged debates pertaining to Arabic and Islamic approaches to the concepts of the soul and spirit, but it is worth noting that rūḥ is widely identified as referring to both ‘soul’ and ‘spirit’, with nafs also being used at times to translate ‘soul’ (see Hard, ‘Contrastive Lexical’; cf. M. S. Zahir al-Din, ‘Man in Search of His Identity: A Discussion on the Mystical Soul (Nafs) and Spirit (Ruh)’, Islamic Quarterly, 24.3 (1980), 96; Abdulaziz Daftari, ‘The Dichotomy of the Soul and Spirit in Shi’a Hadith’, Journal of Shi’a Islamic Studies, 5. 2 (2012), 117–29.

62 Daftari, ‘The Dichotomy of the Soul and Spirit in Shi’a Hadith’, p. 117.

63 Other similar examples of the translation of ‘spirit’ are found in Chs. 10, 12, and 19.

64 Al-Baʿalbakī, Jane Eyre (2006), p. 245.

65 Jacques Derrida, ‘Des Tours de Babal’, trans. by Joseph F. Graham, in Difference in Translation ed. by Joseph F. Graham (Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press, 1985), pp. 165–205 (p. 165).

66 As Bennington notes, however, ‘we shall have to say that the proper name belongs without belonging to the language system.’ See George Bennington and Jacques Derrida, Jacques Derrida (Chicago: Chicago University Press, 1999), p. 170.

67 Also see Gérard Genette, ‘Introduction to the Paratext’, New Literary History, 22.2 (1991), 261–72.

68 In contemporary Arabic, the term also refers to ‘the address’, hence a marker of emplacement. It refers to the ‘structure on or in which something is firmly placed’, and ‘the process through which something is set in place’, ‘the location’.

69 One of the five pillars of Islam is to pray five times a day, a process which involves physically kneeling and prostrating, touching the ground with one’s forehead. In some instances, some believers undertake such regular and vigorous prostration that this can leave a visible mark or sign on their foreheads.

70 For the purposes of this section of the chapter, the translations of Jane Eyre that I have consulted are as follows: Ismāʿīl Kāmil, Jane Eyre (Cairo: Kitābī Series, 1956); al-Dimirdāsh, Jane Eyre; Unnamed group of translators, Jane Eyre aw Qiṣṣat Yatīma (Jane Eyre, or Story of an Orphan) (Beirut: Al-Mʿārif Press, 1984); al-Baʿalbakī, Jane Eyre (1985 and 2006); Unnamed translator, Jane Eyre, ed. by Nabīl Rāghib (Bilingual edition, Cairo: Dār al-Hilāl, 1993); Unnamed translator, Jane Eyre (Damascus: Dār al-Biḥār/Cairo: Dār Wa Maktabat Al-Hilāl, 1999); al-Faḍl, Jane Eyre; Samīr Izzat Naṣṣār, Jane Eyre (Amman: Al-Ahliyya Press, 2005); Rāghib, Jane Eyre; Unnamed group of translators, Jane Eyre (Beirut: Dār Maktabat Al Maʿārif, 2008); Riḥāb ʿAkāwī, Jane Eyre (Beirut: Dār Al-Ḥarf al-ʿArabī, 2010); Ḥilmī Murād, Jane Eyre (Cairo: Modern Arab Foundation, 2012); al-Rifāʿī, Qiṣṣat Jane Eyre (Story of Jane Eyre); Unnamed translator, Jane Eyre (Dubai: Dār Al Hudhud For Publishing and Distribution, 2016); Unnamed translator, Jane Eyre (Giza: Bayt al-Lughāt al-Duwaliyya, 2016); Yūsif ʿAṭā al-Ṭarīfī, Jane Eyre (Amman: Al-Ahliyya Press, 2017); Aḥmad Nabīl al-Anṣārī, Jane Eyre (Aleppo: Dār al-Nahj/Dār al-Firdaws: 2017); Unnamed translator, Jane Eyre (Cairo, Dār al-Alif for Printing and Distribution, 2017); Munīr al-Baʿalbakī, Jane Eyre (Morroco: Maktabat al-Yusr, n.d. print on demand).

71 Given the lack of a direct equivalent or the name ‘Jane Eyre’, as I discuss below, here I have opted to maintain the English spelling of the name as it is.