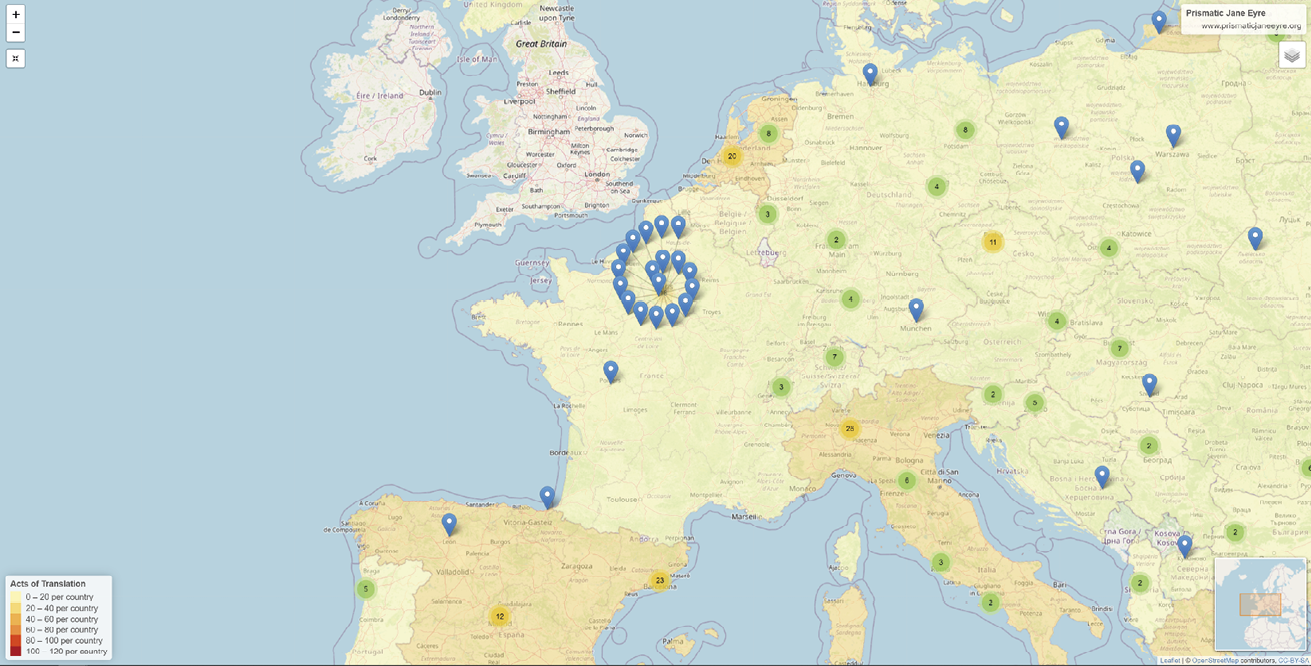

The World Map https://digitalkoine.github.io/je_prismatic_map Created by Giovanni Pietro Vitali; maps © Thunderforest, data © OpenStreetMap contributors

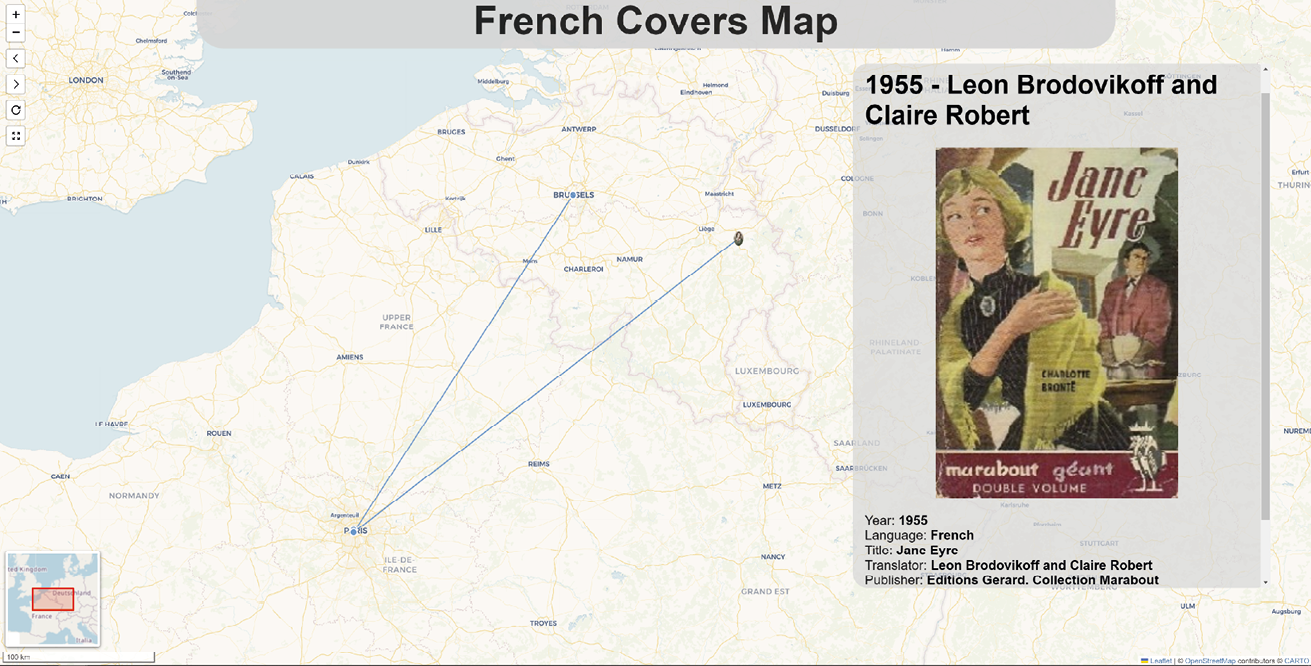

The French Covers Map https://digitalkoine.github.io/french_storymap/Researched by Céline Sabiron, Léa Rychen and Vincent Thierry; created by Giovanni Pietro Vitali and Simone Landucci

4. Translating the French in the French Translations of Jane Eyre

© 2023 Céline Sabiron, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0319.07

Introduction: ‘it loses sadly by being translated’

‘(I wish I might write all she said to me in French — it loses sadly by being translated into English)’, Charlotte Brontë’s narrator regrets in an aside, in her posthumously published novel The Professor (1857).1 Nevertheless, she does sometimes boldly grant herself the freedom to write in French, as in her more bestselling Jane Eyre (1847), which was written after The Professor but published ten years before it, since her first novel had been repeatedly turned down by publishing houses. Impulsive young Adèle babbles in French to discuss the ‘cadeau’2 that Mr Rochester has bought her and that consists of a ‘robe’: ‘“Il faut que je l’essaie!” cried she; “et à l’instant même!”’.3 However, Charlotte Brontë does not overuse this linguistic license and often reverts to English, as in Shirley (1849) where she translates the French conversation between Hortense Moore and Caroline Helstone: ‘[t]he answer and the rest of the conversation was in French, but as this is an English book, I shall translate it into English’, she explains through the voice of her narrator.4 Translation is therefore presented as both a loss (‘it loses sadly by being translated’) and an injunction (‘shall’) imposed by the dictates of the publishing industry in an English context and that she has to subject herself to. This goes against her spontaneous inner wish to write a multilingual text in which her language of expression would vary within the very same text depending on the object of her writing.

Nevertheless, this caution about language did not prevent her from receiving harsh and somewhat exaggerated criticisms from a few English reviewers mocking her ‘peculiar’5 style and her ‘unintelligible’6 language linked to her extensive use of French. Her English-speaking audience was not the only one tearing their hair out over her text, however popular it was in the United Kingdom. The novel was also extremely testing for the translators who endeavoured to translate it for a French readership, eager in the context of utmost social discontent and political upheavals to emulate the stable Victorian values conveyed in the novel. Published in 1847, Jane Eyre was not officially translated into French until 1854, even if French newspaper publisher and reviewer Eugène Forcade alludes to the novel as early as 1849 in his review of Shirley for Revue des Deux Mondes.7 While well-off French readers could afford to buy the English 1847 Smith, Elder edition circulating from the start on the Continent in selected bookshops in large French cities like Paris, the majority of copies available in France came from the Leipzig firm of Tauchnitz that had been allowed to distribute cheap and portable original novels since the 1844 International Copyright Act.8 Within four months of the English publication of Jane Eyre in 1847, the French could thus access the English text that might then be read out and translated on the spot during family gatherings. They could also read an abridged version, adapted in French by Paul Émile Daurand Forgues, nicknamed ‘Old Nick’, that ran as a feuilleton from April to June 1849 in Le National (Paris) as well as the Belgian Revue de Paris and L’Indépendance belge,9 before being published as a single volume in 1855 by the Paris-based firm Hachette. When the first adaptation by ‘Old Nick’ (1849) and the first translation by Madame Lesbazeilles-Souvestre (1854) came out in France, no review mentioned the use of French in the original text. In Journal des débats politiques et littéraires, Louis Ratisbonne praised the former’s skill at shortening the text and the latter’s elegance and fidelity to the original.10 These remarks, and especially the unspoken topic of the language choice, raises the question of the way the French used by Charlotte Brontë in her text was translated in the French versions of her novel. ‘How do you translate French into French?’ Véronique Béghain aptly wondered in her 2006 study of Charlotte Brontë’s Villette.11

Seventeen different translators have gritted their teeth and worked on Jane Eyre, but the present study will mostly focus on seven of them, leaving aside Old Nick’s adaptation, and dedicating rather little time to the 1919 French version (Flammarion) by two feminist activists, the sisters Marion Gilbert and Madeleine Duvivier, and the 1946 Redon and Dulong’s translation, published simultaneously in Lausanne (J. Marguerat), Switzerland, and in Paris (Édition du Dauphin) because of their almost systematic tendency to simplify the original text by omitting large parts. This analysis will therefore concentrate on Noëmi Lesbazeilles-Souvestre’s first ever translation in 1854 (first published by D. Giraud and now accessible electronically), Léon Brodovikoff and Claire Robert’s 1946 translation, as well as the more recent 1964 (Charlotte Maurat, with Hachette, Paris), 1966 (Sylvère Monod, with Garnier-Frères, Paris), and 2008 (Dominique Jean, with Gallimard, Paris) French versions. It will deliberately not discuss the translators’ biography or the identity and history of the publishing houses through which their works came out, even though they do play a major part in the text production.12 Neither is our aim to compare and contrast individual translation choices. Rather, following the concepts and theories developed by translation and reception specialists, this article proposes to combine literary, linguistic, and translatological approaches and study the French translators’ responses to Charlotte Brontë’s interplay between familiarity and otherness, proximity and distance, feelings of closeness and estrangement when she both ‘imposes and forbids translation’, thus making the latter altogether both necessary and impossible in Jane Eyre.13 In order to do that, it will rely on the three different levels of significance of the French language in the original text (‘effet de réel’, cultural and ideological, or ontological differences) as highlighted by three ground-breaking articles on the subject: Véronique Béghain’s 2006 theoretically-based essay on the translation of the French language in Villette, and two literary studies published in 2013: Emily Eells’s examination of the signification of the French in Jane Eyre, and Hélène Collins’s focus on plurilingualism in The Professor and the various strategies used by the author to allow coherence between the foreign words and their co-texts, or their translations within the novel.14 The chain of signification from the author to the French reader will be examined through a detailed analysis of the translators’ practices and illustrated with a comparative study of examples taken from the original text and its various French translations.

Speaking French: A Signifying Linguistic Spectrum in Jane Eyre

Even though other foreign languages, like German and ‘Hindostanee’, appear in Charlotte Brontë’s hetero-glossic work, French dominates so much that it constantly invades and interferes with the English script revolving, as is often the case in Brontë’s novels, around the teaching of French. In Jane Eyre, she weaves a French linguistic thread throughout her text by recreating a French domestic bubble at Thornfield Hall. Jane thus joins Mr Rochester’s home as a governess to teach his ward Adèle, the daughter of French opera dancer Céline Varens whom he had an affair with in Paris.15 The little French girl came to Thornfield with her French nurse, Sophie, six months before Jane’s arrival. Jane Eyre is thus strewn with vocabulary, phrases, and idiomatic expressions borrowed from French, which even contaminates the English text through clumsy constructions based on French grammatical structures. The text exemplifies a whole range of language proficiency from Adèle’s native French, which she speaks in full phrases, to Jane’s fluency as the result of her dutiful language learning and mimicry of French native speakers (‘Fortunately I had had the advantage of being taught French by a French lady […] applying myself to take pains with my accent, and imitating as closely as possible the pronunciation of my teacher’16). Mr Rochester’s approximate mastery of French features in the middle of the linguistic spectrum provided. He is conversant in several foreign languages, including Italian and German through the liaisons he has had, and he thus mostly sprinkles French words throughout his conversations with his ward.17 As brilliantly demonstrated by Emily Eells in her article dedicated to the significance of Brontë’s use of French, the latter is ‘not merely ornamental and circumstantial’. It serves to ‘encod[e] issues of gender and education, and [to voice] the conflict of individualism and conformity in a Victorian context. True to cliché, it is [also] the language of romance’18 and it embodies passion, fantasy and everything that is associated with French values, mores, and customs at the time as opposed to reason, morality, and reality represented by the English language. As a result, French is not just thoughtlessly sprinkled throughout her text to create a Barthesian ‘effet de réel’. It is rooted in Brontë’s deep interest in languages, and French in particular, which she had learnt at Professor Constantin Héger’s boarding school in Brussels in 1842 and 1843.19 It also comes from her real fascination for foreign words, their musical signification, as well as their textual, almost physical, presence on the material page.

Visualising the ‘effet de réel étranger’ (Collins): The Translator’s vs. the Editor’s Roles

In Jane Eyre, a French signifier is often preferred to its English equivalent owing to its additional aesthetic value, as demonstrated by Hélène Collins in her analysis of plurilingualism in Charlotte Brontë’s The Professor.20 The English text is thus interspersed with French words because of the exotic sensation and the feeling of otherness they convey to readers. The experience of reading foreign written characters is meant to mimic the experience of hearing the syllable-timed language that is French. This ‘effet de réel étranger’, as coined by Collins, is used when ‘Adèle […] asked if she was to go to school “sans mademoiselle?”’.21 Direct speech — as symbolized by the inverted commas — enables Adèle’s voice and language to be heard. What is interesting to mention at this point is that, contrary to the first edition, or the more scholarly Clarendon Edition, the widely available, affordable, and therefore very popular, World’s Classics edition of Jane Eyre (published in paperback by Oxford University Press since 1980, and constantly reissued with the latest edition dating from September 2019) translates Brontë’s plurilingual text. While ‘mademoiselle’ is a lexical borrowing that is transparent in English, the more recent English editions have followed the preposition by an asterisk (*) and an explanatory endnote saying ‘sans: without’. Even though ‘sans’ has been found in English since the early fourteenth-century, it is extremely rarely used and is mostly part of the cultural, and in particular literary, baggage that a Jane Eyre reader is expected to have, with the anaphorical repetition of the preposition ‘sans’ emphatically closing the last line of Jaques’s ‘All the world’s a stage’ speech in Shakespeare’s As You Like It (‘Sans teeth, sans eyes, sans taste, sans everything’, II.7). The implied modern readership is thus felt to be more monolingual and less well versed in classic literature, hence the necessary note added in more recent editions. When the phrase is taken up by Mr Rochester immediately afterwards ‘sans’ no longer needs a note: the otherness has been recognized and got over. The feeling of otherness is greatly toned down in the French translations: all of them, except Gilbert and Duvivier’s version, simply resort to italics to indicate that the words were written in French in the original. Most translators have then chosen to add a second mark and used either a footnote saying ‘En français dans le texte’22 or a superscript black star.23 Only Sylvère Monod’s translation does not show any other mark, but this was an editor’s choice rather than the translator’s. His work came out with ‘Pocket’, a French generalist publisher of literature in pocket format that targets a broad range of readers by producing cheap fiction and non-fiction books composed of uncluttered, almost bare, texts with very few endnotes, and no introduction or critical apparatus. In the French translations, then, exoticism is visually conveyed, through written marks (italics, stars, and notes), whereas in the original English it is phonetically conveyed, through the bare use of French words, i.e., through French rhythm and sound. The translation work affects the reader’s sensory experience as it shifts from the ear to the eye, from a sonorous to an ocular effect. In the French translation, otherness is the fruit of decisions that involve both translators and editors; it is moved out of the author’s text to feature as part of what Genette calls ‘paratext’ since it is imprinted into the text, materially inscribed as part of the printed page.

Translating Otherness: A Shift to the Paratext, or even Off the Text

In the English Jane Eyre, French words are not only used for their aesthetic value, their exoticism, and musicality. They are often strategically employed by the author who, as Collins says, ‘relegates the signified of the foreign word to an irreducible otherness’ (my translation; ‘reléguer le signifié du mot étranger dans une irréductible altérité’).24 The phrase ‘“Jeune encore,” as the French say’, thus sounds very derogatory, not to say condescending, in Mr Rochester’s mouth, since it is loaded with illocutionary force by being put aside (through the lack of translation) and labelled as belonging to a different people.25 The meaning of the French expression — used out of politeness and respect to mean ‘not old yet’ — is thus perverted and even inverted in this very case owing to Mr Rochester feeling jealous towards St John Rivers. The French translators have mostly chosen to displace the issue from lexico-modal terms to grammatical terms by using the indefinite personal pronoun ‘on’ (Monod’s ‘Jeune encore, comme on dit en français’;26 or Maurat’s ‘Jeune encore1, comme on dit en français’, with the note ‘En français dans le texte’27). The latter serves to exclude the speakers, to move away the referent and eventually disembody the French who are reduced to an empty signifier. Dominique Jean used a similar kind of grammatical distanciation through the personal pronoun ‘le’ that substitutes the French phrase, thus belittling it by reducing it to a two-letter word: ‘“Jeune encore*”, comme le disent les Français’.28

If the translations usually try to bring forward the negative connotation often associated with the use of French in the English text, in particular through grammatical means, they often fail to convey the moral or cultural clichés that the British, and Charlotte Brontë in particular, tend to attach to the French and that are reflected in the author’s use of the French language. ‘The production of translations involves the cognitive representation of perceived potential reception (in other words, the translator’s mental construction of “the reader” and their horizon of expectations), which affects decision making during translation and is inscribed in the translation in the form of an “implied reader”’.29 Jane Eyre’s French translators thus tend to privilege a linguistic take over socio-cultural and ideological approaches to translation. There cannot be any ‘dynamic equivalence’30 between the messages conveyed in the source text and the translated text because the ideology and culture targeted in Brontë’s novel are those inherently carried by the translators and readers of the translated text. As defined by Eugène A. Nida, ‘dynamic equivalence’ is the process by which ‘the relationship between receptor and message should be substantially the same as that which existed between the original receptors and the message’.31 Besides, as Iser argued of all texts (1972 and 1978), a translation is not complete once the translator has finished his task: it is the result of two cognitive processes, consisting of both production and reception. A translation is thus ‘reconstituted every time it is read, viewed, or heard by a receiver, in an active and creative process of meaning making’.32 The meaning of a translation is not inherent in the text; it is conjured up by the interaction between the text and the reader coming with their own linguistic and cultural backgrounds. These necessarily affect their reading and construction of meanings, as illustrated in the following example that points at the ineluctably partial ‘dynamic equivalence’ between the messages conveyed in the source and target texts because of a difference in mental representations.33 ‘I wished the result of my endeavours to be respectable, proper, en règle’, the narrator, Jane Eyre, says as she contemplates Mrs Fairfax’s response to her advertisement.34 Her use of the French expression ‘en règle’ is fraught with meaning as it comes at the end of her sentence, just before the full stop. It adds extra weight and features as a final point to her rather strong declaration which is structured around a ternary rhythm with a double decrescendo-crescendo effect: first grammatically from the two quadrisyllabic (‘respectable’) and disyllabic (‘proper’) mono-phrastic adjectives to the two-word phrase (‘en règle’), and then linguistically from two English words subtly blending into French lexis (‘respectable’ and ‘propre’) to the borrowed French expression meaning in order, in accordance with the rules. There is a clear gradation from what is considered socially and morally acceptable (British values associated with the English language) to what is legally acceptable (Law French). The two adjectives also serve to throw some light on the meaning of the French expression through a paraphrastic technique (using more or less close levels of equivalence), should the latter remain inaccessible to an English reader. Some French translators have chosen to compress the sentence by using one encompassing adjective (‘honorable’ Lesbazeilles-Souvestre). In that case, they have considered that the main function of the surrounding words was that of a co-text paraphrasing — through the use of more or less close equivalences — the French phrase. Others have kept ‘en règle’ with italics and an endnote, thereby only pointing at the change of language.35 However, Dominique Jean has chosen a different strategy; he has used a synonymous expression ‘dans les formes’ meaning ‘done according to custom’ (‘honorable, convenable, dans les formes’), thus displacing the topic from the legal field to that of tradition.36 Besides, he has actually replaced the clichéd cultural reference by an intertextual reference to a literary classic. In the French text, the endnote specifies that Brontë here alludes to Samuel Richardson’s Pamela in her portrayal of a young woman, with no protection, in the service of an unscrupulous master.37 Jean has thus mimicked Brontë’s process of associating the expression with France, through her use of French and reference to legality (as a typically French concern), by linking his chosen phrase to a canonical English text and to tradition. It is interesting to note that because of his academic background, the relatively recent discoveries (dating to the 1990s)38 in the fields of translation and cognition, and his own take on the cognitive processing at stake in the reception of translation, Jean is the only translator who reproduces the distanciation effect through a parallel reversed strategy.

The French translations of Jane Eyre under study thus tend to move any signs of exoticism to the paratext, leaving the editor, as well as the translator, in charge of expressing foreignness through visual tokens, while they ignore any cultural and moral connotations — which are part of the readers’ mental representations, of their cognitive baggage — by removing any subjective evocations linked to the readers’ nationality. Hence the potential pitfall which Véronique Béghain calls ‘the greying risk’ (‘risque de grisonnement’) that covers up nuances and standardizes differences.39 This overall tendency must yet be qualified with the 2008 translation which does resort to ‘transfer’ strategies, taking into account the cognitive dimension of producing and receiving translated materials, with Jean displaying what Wolfram Wilss calls ‘a super-competence’,40 that is, the ability to transfer messages between the linguistic and textual systems of the source culture and the linguistic and textual systems of the target culture.

Translating ‘Frenglish’: Continuum (ST) vs. Continuity (TT)

In Brontë’s English text, French words are not only scattered throughout, they are gradually woven into the fabric of the English text, so that the language-origin is smoothed out to create a form of continuum between French and English, a sort of ‘Frenglish’. The author thus tends to privilege English words from Latin and/ or French origin (‘mediatrix’;41 ‘auditress and interlocutrice’42) in order to erase the language boundary as if she dreamt of creating a form of universal language. She therefore often resorts to words that, through various past cultural contacts and transfers, have been borrowed from the French language. They usually pertain to the fields of clothing (‘pelisse’; ‘a surtout’; ‘calico chemises’43), hairstyle (‘a false front of French curls’44), food and gastronomy (‘forage’; ‘repast’45), love (‘“grande passion”’46); architecture (‘a boudoir’;47 ‘consoles and chiffonières’;48 ‘lustre’;49 ‘balustrade’50), and character traits (‘minois chiffoné’51), to name but a few.

French gradually contaminates the text as the narrator imports French words and even full expressions verbatim into her sentences (‘This, par parenthèse, will be thought cool language’52), so much so that the italics indicating foreign borrowings progressively disappear, French words being even anglicized and spelt with a mix of English and French letters: Adèle is said to sing with ‘naiveté’,53 instead of naïveté in French, through an act of transliteration, i.e., the conversion from one script to another involving swapping letters ([i] instead of [ï] and [é] instead of [e]). The Englished form ‘naivety’, attested in English from 1708, has been avoided, as well as the English spelling (‘naivete’) of the French word. Brontë has deliberately chosen the Old French spelling (‘naiveté’), literally meaning ‘native disposition’, thus indirectly raising the issue of the origin and subtly pointing at Adèle’s French descent. The foreign character of the letter [é] has also been preferred for its French musicality. The diacritical mark — mostly found in the Latin, Greek, and Cyrillic alphabets and their derivatives — allows the distinction between the phoneme with the closed tone /e/ which is that of naiveté and the /ə/ sound (‘naivete’). It serves to convey the French imprint on the musical rhythm of the language. In the translations, however, this continuum between languages becomes a continuous flow within the same language since they tend to erase all traces of foreignness by choosing existing French equivalents. The noun ‘naiveté’ is thus systematically translated into ‘naïveté’.54 Similarly, the adjective ‘piquant’ from Middle French is often translated as such, with French grammar applied (‘piquante’ in Maurat’s and Monod’s translations), or with a synonym (‘bizarre’ in Gilbert and Duvivier’s).55 Jean has opted for a different expression (‘avait du piment’) that ignores the etymology, and therefore the French history, of the term in order to privilege an equivalent semantic effect for the modern French reader.56 The adjective ‘piquant’ was carefully chosen by the author: even if the narrator Jane uses it to mean ‘stimulating’, as in piquing her interest, the word can also mean ‘pricking’, thus programmatically alluding to future episodes in the plot and the eponymous character’s pain to come.

Jane Eyre’s English is so contaminated by French that it is affected by it in strange and subtle ways, as when the young protagonist mentions her dream of being able to ‘translate currently a certain little French story-book which Madam Pierrot had that day shewn [her]’.57 The lexical mistake — caused by the fact that ‘currently’ and ‘couramment’ are cognates, i.e., false friends with ‘couramment’ actually meaning ‘fluently’ in French — is identified as such by an asterisk (and an endnote in the Oxford World’s Classics edition even though there was none in the editions approved by Charlotte Brontë). Yet, it has been fully ignored by all the French translators who have chosen to translate the expression as ‘traduire couramment’ with no reference to the confusion between the bilingual homophones. Only Jean shifts the lexical confusion by playing on the metaphor of the book through the figurative expression ‘traduire à livre ouvert’, meaning ‘translate easily and perceptively’.58 Semantic continuity thus prevails in the French translations that do not bring out the blending of meanings within the same language.

Charlotte Brontë’s text relies on semantic but also grammatical continuum since it is fraught with ‘barbarisms’, i.e., words and even phrases that are ‘badly’ formed according to traditional philological rules as they are coined with a mixture of French and English elements. The sentence ‘The old crone “nichered” a laugh’ points at both the gap and the proximity between languages: the French verb ‘nicher’ (to hide in), conjugated in the preterite tense with its English-ed ending, is phonetically (and lexically) very close to Old English ‘snicker’, meaning ‘to laugh in a half-suppressed way’.59 However, this overlapping of languages automatically disappears in the French translations, which, at best, focus on conveying the concealed nature of the character’s laughter, when they do not bypass the issue (Redon and Dulong, Monod), or displace it altogether. For instance, Jean has chosen to change the characteristics of the woman’s laughter described as neighing or whinnying, following his process-oriented method.

|

Translators |

|

|

‘La vieille femme cacha un sourire’ (etext) |

|

|

‘La vieille sorcière eut un rire étouffée’ (p. 208) |

|

|

‘La vieille fit entendre un rire sarcastique’ (p. 181) |

|

|

‘La vieille commère fit entendre un ricanement’ (p. 334) |

|

|

‘La vieille riait’ (p. 234) |

|

|

‘La vieille sorcière ricana’ (p. 230) |

|

|

‘La vieille commère lança […] un rire comme une sorte de hennissement’ (p. 331) |

Lexical and grammatical barbarisms can occur when the narrator expresses a feeling of rebellion and yearns for freedom, her expression mimicking the content of her thoughts and flouting any language rule, as in ‘I was a trifle beside myself; or rather out of myself, as the French would say’ or ‘I was debarrassed of interruption’.60 The past participle ‘debarrassed’, here used to mean ‘relieved’ or ‘free’ is a mix of French ‘débarrassé’, and the more usual English form ‘disembarrassed’, employed by Jane later on (‘I sat down quite disembarrassed’) in the sense of ‘freed from embarrassment’.61 The two notions of freedom and self-respect, thus blended together in the newly coined word, organically grow from the surrounding English text made up of words shared with French such as ‘with satisfaction’, ‘revived’, and the opposites ‘Liberty’/‘Servitude’.62 None of the French translations hint at the barbarism created by the merging of the two languages. While Monod has ignored the sentence altogether, Brodovikoff and Robert have simplified and thereby neutralized it (‘je n’allais plus être interrompue’).63 The other translators have opted for one interpretation or the other, privileging either the idea of shelter and protection (‘j’étais désormais à l’abri de toute interruption’ in Lesbazeilles-Souvestre; ‘Je n’étais plus en butte aux interruptions’ in Jean) or that of freedom (‘ainsi délivrée de toute interruption’ in Maurat).64 Brontë’s patchwork approach to languages gives way to a seamless fabric of French words in the translations.

This sense of a language continuum between French and English fails to be translated in the French versions. What is often translated, though, is imagery; that is to say the language that produces pictures in the minds of people reading or listening to the text, as demonstrated through the verb ‘disembowel’ used by Mr Rochester to summon Adèle to unwrap her ‘boîte’.65 Even if the word has been attested in English since the 1600s to mean ‘eviscerate, wound so as to permit the bowels to protrude’, it is deliberately employed by Brontë because it sounds like a portmanteau word in the master’s mouth.66 Mr Rochester wishes to play on French images (through the phonetic pun, the near-homophony between ‘disembowelling’ and the French verb ‘désemballer’, ‘to unwrap’) mixed with references to guts and interior parts as an ironic allusion to Adèle’s illegitimate origin. About half of the translations under study have simply focused on the idea of unwrapping (‘déballer’ in Lesbazeilles-Souvestre), of opening up (‘ouvrir’ in Redon and Dulon) a present, with only Brodovikoff and Robert twisting its meaning a bit through the use of the verb ‘inventorier’, that is ‘to list’, thus pointing at the formal staging of Adèle’s gesture.67 The other translators have rather cleverly played on the imagery of the bowels by picking up the analogy and stretching it further into their translations, from the rather descriptive phrase ‘vider les entrailles’ (in Maurat) to the slightly more brutal and gory-sounding phrases ‘éventrer’ (in Monod) — literally meaning ‘to gut’, ‘cut open’ or ‘to rip open’ when used figuratively — or ‘éviscérer’ (in Jean), i.e., ‘to eviscerate’.68 If there is no language continuum but rather a language continuity through the single use of French in the translations and the absence of any reference to the subtle blending of languages in the source text, the translations mostly focus on the language of mental images.

Conclusion: Foreign Language Instruction and the Reader’s Role in Jane Eyre

The question of which language to favour and Charlotte Brontë’s refusal to resort to translation systematically is recurrently raised throughout her work in a metafictional discourse that betrays the author’s inner turmoil between her wish to keep foreign words for linguistic authenticity, to be coherent with her co-text, and the risk she runs of making her text inaccessible to those of her readers who knew only English due to an irreducible sense of unfamiliarity, and even otherness. This hesitation reveals the author’s deep reflection around the use of untranslated French words. She constantly reconsiders her choice of language, which is never only artificial but serves a purpose, as demonstrated by Emily Eells. Through her ‘superimposition of languages’, her choice not to use equivalences and to keep a feeling of otherness in her text,69 she privileges cultural decentering and asks for the reader’s cooperation as analysed by Umberto Eco.70

Brontë dreams of freeing languages viewed as tools that must serve a subject matter, an idea, or an emotion. For the latter to bloom and take on their full meanings, the author feels she cannot be constricted to one language system, but conversely wished she could dig into multiple language systems, ideally viewed as a continuum. She thus relies on her readers to produce textual meaning, and when there are no editorial signs to guide them, they must look for interpretative clues — be they etymological, phonetic (through near-homophonies), or contextual — to unlock the meaning of the passage. In her book The Foreign Vision of Charlotte Brontë (1975), Enid Duthie points at the author’s great skill at introducing foreign words since she almost systematically places interpretative keys to domesticate the foreign text and thus make the signified more accessible to English-speaking readers. The latter must then trust that the author has done everything in her power to facilitate their entry into the text (Collins), and rely on their expertise in the domain of reading and their own comprehension abilities. ‘She [Adèle] would have Sophie to look over her ‘toilettes’ as she called her frocks; to furbish up any that were ‘passées’, and to air and arrange the new’, can be read in Chapter 17. After first giving the readers a leg-up and guiding them within the text through an act of self-translation — ‘toilettes’ being immediately given its English equivalent ‘frocks’ — Brontë gradually leads the readers to autonomy. ‘Reading is a pact of generosity between author and readers; each one trusts the other, each one counts on the other’, wrote Jean-Paul Sartre in Qu’est-ce que la littérature? (1948).71 The past participle ‘passées’ therefore no longer needs to be translated, but its meaning can be inferred from the context and the structure of the sentence, i.e., the opposition between ‘passées’ and ‘new’ which echoes through a grammatical parallelism, referring to Adèle’s clothes. French and English signifiers work together to produce meaning; hence their complementarity, and the creation of a Franco-English union within the source text. This whole framework set up by the author for reader autonomy is absent from the French translations. The French reader is effortlessly given the meaning of the word, as in Lesbazeilles-Souvestre’s translation (‘ses toilettes, ainsi qu’elle appelait ses robes, afin de rafraîchir celles qui étaient passées et d’arranger les autres’). While Léon Brodovikoff and Claire Robert have opted for a lexical translation that goes unnoticed for the reader through the use of the synonym ‘défraîchies’, that is to say ‘faded’ (‘ses toilettes, comme elle appelait ses robes, pour renouveler celles qui étaient défraîchies et arranger les neuves’ Brodovikoff and Robert), other translators have chosen to keep the French word, but to use a visual sign to point at its foreign origin, such as italics, and, as aforementioned either a footnote ‘en français dans le texte’ (Redon and Dulong, and Maurat) or a superscript black star (Jean).72

In their take on the target culture, translators have mostly switched from the ‘domesticating (19th and early 20th centuries)/foreignizing’ (1960s) strategies, as developed by Lawrence Venuti,73 to the archaizing (1960s)/modernizing (1990s–2000s) approaches in the latest French versions. While the translators’ former stress was on culture — ‘domesticating’ the text to make it closely conform to the target culture, or conversely ‘foreignizing’ the text to respect the source culture as advocated by Friedrich Schleiermacher and other German Romantics before being theorized by Antoine Berman as an ethics of translation in the 1980s74 — their current emphasis seems to be more on lexis, opposing outdated to modern day vocabulary and lexical uses. Charlotte Brontë’s pedagogical approach into textual deciphering is not translated into the French versions of her work, so that readers are not educated to reading. They are spoon-fed by the translators who have worked around the problem and also ‘défraîchi’ the text by fading out the latter’s sense of otherness. They remain passive and external to the foreign character of the text before them. Meaning is not gradually allowed to emerge through the harmonious blending of the two languages since it is already a priori given. The Franco-English linguistic union is definitely broken in the translation which privileges one language viewed as independent from the other. ‘Perhaps, therefore, it is more useful to understand the role of foreign language instruction and not simply the role of language in the original version and in the translation of Jane Eyre when trying to comprehend its transnational reception’, Anne O’Neil-Henry writes.75 As the teaching-learning process fails to be reproduced in the French translations and despite the recent tendency to take the audience’s response into account, it seems that there is an urgent need for the translators to implement a full ‘dynamic equivalence’ between the source text and the target text, and acknowledge the cognitive processing in the production and the reception of translation.

Works Cited

Translations of Jane Eyre

Brontë, Charlotte, Jane Eyre, trans. By Noëmi Lesbazeilles-Souvestre (Paris: D. Giraud, 1854). The version used here is the electronic 1883 version published by Hachette.

——, Jane Eyre, trans. By R. Redon and J. Dulong (Paris: Éditions du Dauphin, 1946).

——, Jane Eyre, trans. By Marion Gilbert and Madeleine Duvivier (Paris: GF Flammarion, [1919] 1990).

——, Jane Eyre, trans. By Léon Brodovikoff and Claire Robert (Verviers, Belgique: Gérard & Co., [1946] 1950).

——, Jane Eyre, trans. By Charlotte Maurat (Paris: Le Livre de Poche, [1964] 2016).

——, Jane Eyre, trans. By Dominique Jean (Paris: Gallimard, [2008] 2012).

Other Sources

Allott, Miriam, ed., The Brontës: The Critical Heritage (London: Routledge, 1974), https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315004570

Armstrong, Nancy, Desire and Domestic Fiction: A Political History of the Novel (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1989).

Barthes, Roland, ‘L’effet de réel’, Communications, 11 (1968), 84–89, https://doi.org/10.3406/comm.1968.1158

Béghain, Véronique, ‘How do you translate French into French? Charlotte Brontë’s Villette as a borderline case in Translatability’, Interculturality & Translation, 2 (2006), 41–62.

——, ‘“To retain the slight veil of the original tongue”: traduction et esthétique du voile dans Villette de Charlotte Brontë’, in Cahiers Charles V, ‘La traduction littéraire ou la remise en jeu du sens’, ed. by Jean-Pierre Richard, 44 (2008), 125–42, https://doi.org/10.3406/cchav.2008.1518

——, ‘“A Dress of French gray”: Retraduire Villette de Charlotte Brontë au risque du grisonnement’, in Autour de la traduction: Perspectives littéraires européennes, ed. by Enrico Monti and Peter Schnyder (Paris: Orizons, 2011), pp. 85–104.

Bell, Maureen, Shirley Chew, Simon Eliot, Lynette Hunter and James L. W. West, eds., Re-Constructing the Book: Literary Texts in Transmission (Burlington: Ashgate, 2001), https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315192116

Berman, Antoine, La traduction et la lettre ou l’Auberge du lointain (Paris: Seuil, 1991).

——, L’épreuve de l’étranger: Culture et traduction dans l’Allemagne romantique (Paris: Gallimard, 1984).

Brontë, Charlotte, Shirley and The Professor (New York: Everyman’s Library, [1849, 1857] 2008).

Buzard, James, Disorienting Fictions: The Autoethnographic Work of Nineteenth-Century Novels (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2005).

Collins, Hélène, ‘Le plurilinguisme dans The Professor de Charlotte Brontë: entre fascination et neutralisation de l’altérité’, Cahiers victoriens et édouardiens, 78 (2013), https://doi.org/10.4000/cve.818

Derrida, Jacques, ‘Des tours de Babel’, in Psyche: Inventions de l’autre, 2 vols (Paris: Galilée, [1985] 1998), I, pp. 203–35.

Devonshire, Marian Gladys, The English Novel in France: 1830–1870 (New York: Octagon Books, 1967).

Dillon, Jay, ‘“Reader, I found it”’: The First Jane Eyre in French’, The Book Collector, 17 (2023), 11–19.

Duthie, Enid L., The Foreign Vision of Charlotte Brontë (London: Macmillan, 1975), https://doi.org/10.1177/004724417600602107

Eco, Umberto, Lector in Fabula, trans. By Myriam Bouzaher (Paris: Grasset, 1979).

Eells, Emily, ‘The French aire in Jane Eyre’, Cahiers victoriens et édouardiens, 78 (2013), https://doi.org/10.4000/cve.839

——, ‘Charlotte Brontë en français dans le texte’, in Textes et Genres I: ‘A Literature of Their Own’, ed. by Claire Bazin and Marie-Claude Perrin-Chenour (Nanterre: Publidix, 2003), pp. 69–88.

Ewbank, Inga-Stina, ‘Reading the Brontës Abroad: A Study in the Transmission of Victorian Novels in Continental Europe’, in Re-Constructing the Book: Literary Texts in Transmission, ed. by Maureen Bell, Shirley Chew, Simon Eliot and James L. W. West (London: Routledge, 2001), pp. 84–99, https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315192116

Forcade, Eugène, ‘Le roman anglais contemporain en Angleterre: Shirley, de Currer Bell’, Revue des Deux Mondes, 1.4 (Nov. 1849), 714–35.

Fraser’s Magazine for Town and Country, 1830–1869, 40.240 (Dec. 1849), 691–702.

Genette, Gérard, Palimpsestes: La littérature au second degré (Paris: Seuil, 1982).

Gilbert, Sandra M. and Susan Gubar, The Madwoman in the Attic: The Woman Writer and the Nineteenth-Century Literary Imagination (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1979).

Guyon, Loïc and Andrew Watts, eds., Aller(s)-Retour(s): Nineteenth-Century France in Motion (Cambridge: Cambridge Scholars Publisher, 2013).

Iser, Wolfgang, ‘The Reading Process: A Phenomenological Approach’, New Literary History, 3 (1972), 279–99, https://doi.org/10.2307/468316

——, The Act of Reading: A Theory of Aesthetic Response (Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1978).

Jauss, Hans Robert, Toward an Aesthetic of Reception (Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 1982).

Kruger, Haidee and Jan-Louis Kruger, ‘Cognition and Reception’, in The Handbook of Translation and Cognition, ed. by John W. Schwieter and Aline Ferreira (Oxford: Wiley Blackwell, 2017), pp. 71–89.

Lawrence, Karen, ‘The Cypher: Disclosure and Reticence in Villette’, Nineteenth-Century Literature, 42 (1988), 448–66, https://doi.org/10.2307/3045249

Lewes, George Henry, ‘Recent Novels: French and English’, Fraser’s Magazine for Town and Country, 1830–1869, 36.216 (Dec. 1847), 686–95.

Longmuir, Anne. ‘“Reader, perhaps you were never in Belgium?”: Negotiating British Identity in Charlotte Brontë’s The Professor and Villette’, Nineteenth-Century Literature, 64 (2009), 163–88, https://doi.org/10.1525/ncl.2009.64.2.163

Lonoff, Sue, ‘Charlotte Brontë’s Belgian Essays: The Discourse of Empowerment’, Victorian Studies, 32 (1989), 387–409.

Meschonnic, Henri, Poétique du traduire (Paris: Verdier, 1999).

Newmark, Peter, ‘Pragmatic Translation and Literalism’, TTR: Traduction, Terminologie, Rédaction, 1 (1988), 133–45, https://doi.org/10.7202/037027ar

Nida, Eugène A., Toward a Science of Translating (Leiden: Brill, 1964).

Nida, Eugène A. and Charles R. Taber, The Theory and Practice of Translation (Leiden: Brill, 2003), https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004496330

O’Neil-Henry, Anne, ‘Domestic Fiction Abroad: Jane Eyre’s Reception in Post-1848 France’, in Aller(s)-Retour(s): Nineteenth-Century France in Motion, ed. by Loïc Guyon and Andrew Watts (Cambridge: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2013), pp. 111–24.

Ratisbonne, Louis, in Journal des débats politiques et littéraires (4 Jan. 1856).

Sartre, Jean-Paul, Qu’est-ce que la littérature? (Paris: Gallimard, 1948).

Schwieter, John W. and Aline Ferreira, eds., The Handbook of Translation and Cognition (Oxford: Wiley Blackwell, 2017).

Showalter, Elaine, ‘Charlotte Brontë’s Use of French’, Research Studies, 42 (1974), 225–34.

Venuti, Lawrence, The Translator’s Invisibility: A History of Translation (London: Routledge, 1995), https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315098746

Wilss, Wolfram, ‘Perspectives and Limitations of a Didactic Framework for the Teaching of Translation’, in Translation, ed. by Robert W. Brislin (New York: Gardner, 1976), pp. 117–37.

Yaeger, Patricia, Honey-Mad Women: Emancipatory Strategies in Women’s Writing (New York: Columbia University Press, 1988), https://doi.org/10.7312/yaeg91456

1 Charlotte Brontë, Shirley and The Professor (New York: Everyman’s Library, 2008), p. 810.

2 JE, Ch. 13.

3 JE, Ch. 14.

4 Brontë, Shirley and The Professor, p. 64.

5 ‘The style of Jane Eyre is peculiar; but, except that she admits too many Scotch or North-country phrases, we have no objection to make to it, and for this reason: although by no means a fine style, it has the capital point of all great styles in being personal, — the written speech of an individual, not the artificial language made up from all sorts of books’, George Henry Lewes, ‘Recent Novels: French and English’, Fraser’s Magazine for Town and Country, 1830–1869, 36.216 (Dec. 1847), 686–95 (p. 693).

6 ‘The first volume will be unintelligible to most people, for it is half in French and half in broad Yorkshire. There are many who know “Yorkshire”, and don’t know French; and others, we fear, who know French and don’t know Yorkshire’, from an unsigned review, in Fraser’s Magazine for Town and Country, 1830–1869, 40.240 (Dec. 1849), 691–702 (p. 693), cited in The Brontes: The Critical Heritage, ed. by Miriam Allott (London: Routledge, 1974), pp. 153–54.

7 Eugène Fourcade, ‘Le roman anglais contemporain en Angleterre: Shirley, de Currer Bell’, Revue des Deux Mondes, 1.4 (Nov. 1849), 714–35 (p. 714).

8 Inga-Stina Ewbank, ‘Reading the Brontës Abroad: A Study in the Transmission of Victorian Novels in Continental Europe’, in Re-Constructing the Book: Literary Texts in Transmission, ed. by Maureen Bell, Shirley Chew, Simon Eliot and James L. W. West (London: Routledge, 2001), pp. 84–99.

9 Jay Dillon, ‘”Reader, I found it”’: The First Jane Eyre in French’, The Book Collector, 17 (2023), 11–19. See Chapter I in this volume for discussion.

10 ‘l’une, élégante et fidèle due à la plume de Mme de Lesbazeilles; l’autre a été habilement abrégée pour la Bibliothèque des Chemins de Fer par Old Nick (M. Forgues)’, Louis Ratisbonne in Journal des débats politiques et littéraires (4 Jan. 1856), https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k4507688.item

11 Véronique Béghain, ‘How do you translate French into French? Charlotte Brontë’s Villette as a borderline case in Translatability’, Interculturality & Translation, 2 (2006), 41–62.

12 ‘the text may pass through many hands on its way from author to printed form: those of scribe or copyist, amanuensis, secretary, typist, editor, translator, compositor, printer, proofreader and publisher. The work of all these agents alters the text (directly or indirectly, intentionally or not) and — by the addition or deletion of material, by errors and accidents in copying or typesetting, by supplying new contexts (prefaces, dedications, postscripts, indexes) or by repackaging the text among other texts (in compilations and anthologies) — substantially conditions what and how the text means’, Maureen Bell, ‘Introduction: The Material Text’, in Re-Constructing the Book: Literary Texts in Transmission, ed. by Maureen Bell, Shirley Chew, Simon Eliot, Lynette Hunter and James L. W. West (Burlington: Ashgate, 2001), p. 3.

13 ‘Il impose et interdit à la fois la traduction’, Jacques Derrida, ‘Des tours de Babel’, in Psyche: Inventions de l’autre, 2 vols (Paris: Galilée, [1985] 1998), I, 203–35 (p. 207).

14 Véronique Béghain, ‘How do you translate French into French’, 41–62; Emily Eells, ‘The French aire in Jane Eyre’, Cahiers victoriens et édouardiens, 78 (2013); Hélène Collins, ‘Le plurilinguisme dans The Professor de Charlotte Brontë: entre fascination et neutralisation de l’altérité’, Cahiers victoriens et édouardiens, 78 (2013).

15 JE, Ch. 11.

16 JE, Ch. 11.

17 Anne O’Neil-Henry, ‘Domestic Fiction Abroad: Jane Eyre’s Reception in Post-1848 France’, in Aller(s)-Retour(s): Nineteenth-Century France in Motion, ed. by Loic Guyon and Andrew Watts (Cambridge: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2013), pp. 111–24.

18 Eells, ‘The French aire in Jane Eyre’.

19 Eells, ‘The French aire in Jane Eyre’.

20 Collins, ‘Le plurilinguisme’.

21 JE, Ch. 24.

22 Charlotte Brontë, Jane Eyre, trans. by Charlotte Maurat (Paris: Le Livre de Poche, [1984] 2012), p. 309.

23 Charlotte Brontë, Jane Eyre, trans. by Dominique Jean (Paris: Gallimard, [2008] 2012), p. 441.

24 Collins, ‘Le plurilinguisme’.

25 JE, Ch. 37.

26 Charlotte Brontë, Jane Eyre, trans. by Sylvère Monod (Paris: Pocket, [1984] 2012), p. 742.

27 Brontë, Jane Eyre, trans. by Charlotte Maurat, p. 507.

28 Brontë, Jane Eyre, trans. by Dominique Jean, p. 715.

29 Haidee Kruger and Jan-Louis Kruger, ‘Cognition and Reception’, in The Handbook of Translation and Cognition, ed. by John W. Schwieter and Aline Ferreira (Oxford: Wiley Blackwell, 2017), 71–89 (pp. 72–73).

30 Eugène A. Nida and Charles R. Taber, The Theory and Practice of Translation (Leiden: Brill, 2003).

31 Eugène A. Nida, Toward a Science of Translating (Leiden: Brill, 1964), p. 159.

32 Kruger and Kruger, ‘Cognition and Reception’, p. 72.

33 Hans Robert Jauss, Toward an Aesthetic of Reception (Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 1982).

34 JE, Ch. 10.

35 Brontë, Jane Eyre, trans. by Charlotte Maurat, p. 109.

36 Brontë, Jane Eyre, trans. by Dominique Jean, p. 163.

37 The endnote says ‘Allusion à la situation critique de la jeune femme sans protection au service d’un maitre peu scrupuleux, dont le modèle littéraire remontait au roman épistolaire de Samuel Richardson Pamela (voir n.1, p. 38). Charlotte Brontë admirait l’œuvre de Richardson’ [An allusion to the plight of the unprotected young woman in the employment of an unscrupulous master, whose literary model was Samuel Richardson’s epistolary novel Pamela (see n.1, p. 38). Charlotte Brontë admired Richardson’s work], my translation), Brontë, Jane Eyre, trans. by Dominique Jean, p. 807.

38 See Newmark’s concept of pragmatic translation, requiring that ‘the translator must take into account all aspects involving readership sensitivity in order to stimulate the appropriate frame of mind in the reader’, Peter Newmark, ‘Pragmatic Translation and Literalism’, TTR: Traduction, Terminologie, Rédaction, 1 (1988), 133–45 (pp. 133–34).

39 Véronique Béghain, ‘“A Dress of French gray”: Retraduire Villette de Charlotte Brontë au risque du grisonnement’, in Autour de la traduction: Perspectives littéraires européennes, ed. by Enrico Monti and Peter Schnyder (Paris: Orizons, 2011), p. 99.

40 For Wolfram Wilss three complementary competences are needed in translation: receptive competence in the source language (the ability to understand the source text), productive competence in the target language (the ability to use the linguistic and textual resources of the target language), and super-competence as defined above. See Wolfram Wilss, ‘Perspectives and Limitations of a Didactic Framework for the Teaching of Translation’, in Translation, ed. by Robert W. Brislin (New York: Gardner, 1976), pp. 117–37 (p. 120).

41 JE, Ch. 10.

42 JE, Ch. 14.

43 JE, Ch. 5, and Ch. 7.

44 JE, Ch. 7.

45 JE, Ch. 17.

46 JE, Ch. 15.

47 JE, Ch. 11.

48 JE, Ch. 13.

49 JE, Ch. 14.

50 JE, Ch. 17.

51 JE, Ch. 17.

52 JE, Ch. 12.

53 JE, Ch. 11.

54 Brontë, Jane Eyre, trans. by Dominique Jean, p. 185; Brontë, Jane Eyre, trans. by Charlotte Maurat, p. 125; Brontë, Jane Eyre, trans. by Sylvère Monod, p. 177; Brontë, Jane Eyre, trans. by Marion Gilbert and Madeleine Duvivier (Paris: GF Flammarion, 1990), p. 117.

55 JE, Ch. 13; Brontë, Jane Eyre, trans. by Charlotte Maurat, p. 146; Brontë, Jane Eyre, trans. by Sylvère Monod, p. 208; Brontë, Jane Eyre, trans. by Marion Gilbert and Madeleine Duvivier, p. 134.

56 Brontë, Jane Eyre, trans. by Dominique Jean, p. 213.

57 JE, Ch. 8.

58 Brontë, Jane Eyre, trans. by Dominique Jean, p. 141.

59 JE, Ch. 19.

60 JE, Ch. 2, and Ch. 10.

61 JE, Ch. 13.

62 JE, Ch. 10.

63 Brontë, Jane Eyre, trans. by Sylvère Monod, p. 148; Brontë, Jane Eyre, trans. by Léon Brodovikoff and Claire Robert (Verviers, Belgique: Gérard & Co., 1950), p. 106.

64 Brontë, Jane Eyre, trans. by Dominique Jean, p. 158; Brontë, Jane Eyre, trans. by Charlotte Maurat, p. 106.

65 JE, Ch. 14.

66 See ‘disembowel, v.’, https://oed.com/view/Entry/54194

67 Brontë, Jane Eyre, trans. by R. Redon and J. Dulong (Paris: Éditions du Dauphin, 1946), p. 123; Brontë, Jane Eyre, trans. by Léon Brodovikoff and Claire Robert, p. 160.

68 Brontë, Jane Eyre, trans. by Charlotte Maurat, p. 155; Brontë, Jane Eyre, trans. by Sylvère Monod, p. 223; Brontë, Jane Eyre, trans. by Dominique Jean, p. 227.

69 Antoine Berman, La traduction et la lettre ou l’Auberge du lointain (Paris: Seuil, 1991); Henri Meschonnic, Poétique du traduire (Paris: Verdier, 1999).

70 Umberto Eco, Lector in Fabula, trans. by Myriam Bouzaher (Paris: Grasset, 1979).

71 My translation; ‘la lecture est un pacte de générosité entre l’auteur et le lecteur; chacun fait confiance à l’autre, chacun compte sur l’autre’, Jean-Paul Sartre. Qu’est-ce que la littérature? (Paris: Gallimard, 1948), p. 62.

72 Brontë, Jane Eyre, trans. by Léon Brodovikoff and Claire Robert, p. 201.

73 ‘Admitting (with qualifications like “as much as possible”) that translation can never be completely adequate to the foreign text, Schleiermacher allowed the translator to choose between a domesticating method, an ethnocentric reduction of the foreign text to target-language cultural values, bringing the author back home, and a foreignizing method, an ethno-deviant pressure on those values to register the linguistic and cultural difference of the foreign text, sending the reader abroad’. Lawrence Venuti, The Translator’s Invisibility: A History of Translation (London: Routledge, 1995), p. 20.

74 Antoine Berman, L’épreuve de l’étranger: Culture et traduction dans l’Allemagne romantique (Paris: Gallimard, 1984).

75 O’Neil-Henry, ‘Domestic Fiction Abroad’, p. 121.