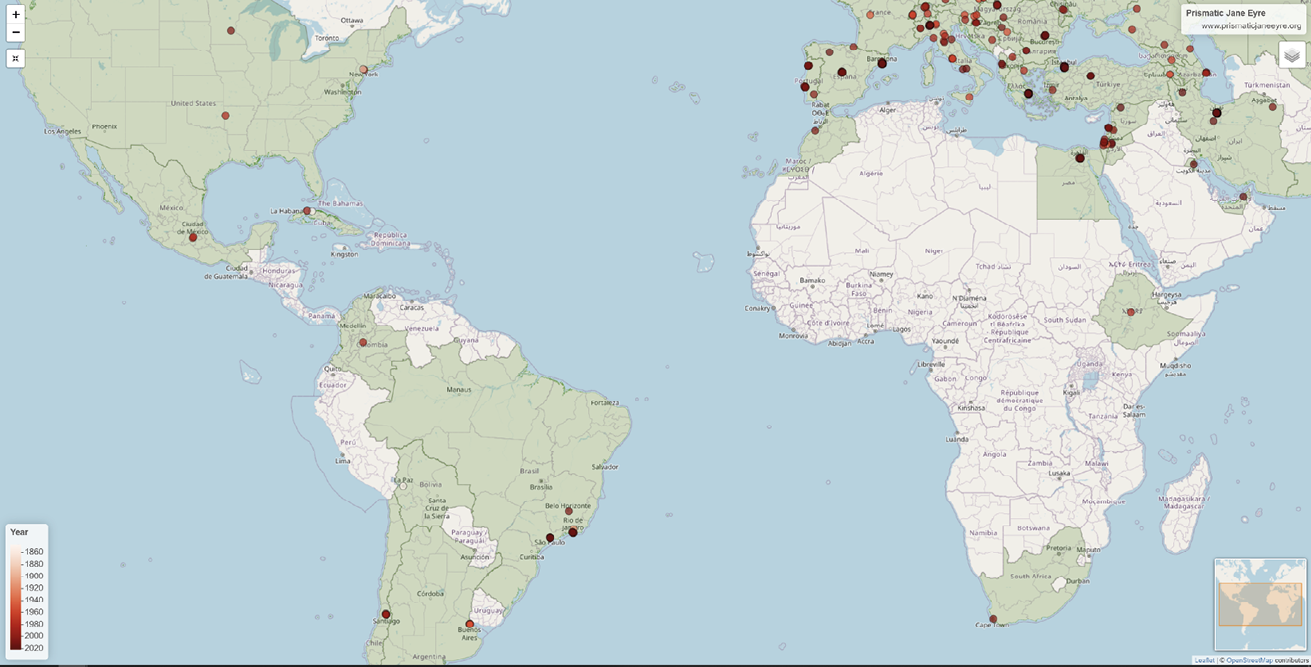

The General Map https://digitalkoine.github.io/je_prismatic_generalmap/ Created by Giovanni Pietro Vitali; © OpenStreetMap contributors

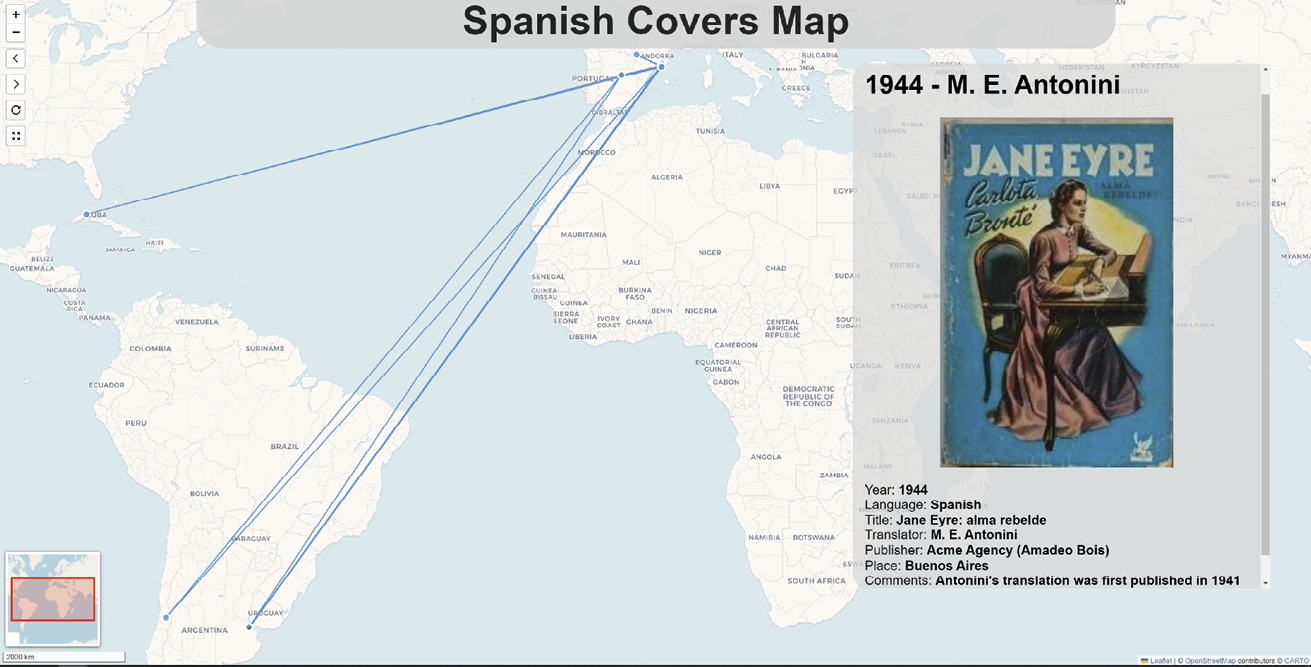

The Spanish Covers Map https://digitalkoine.github.io/spanish_storymap/ Researched by Andrés Claro; created by Giovanni Pietro Vitali and Simone Landucci

5. Representation, Gender, Empire: Jane Eyre in Spanish

© 2023 Andrés Claro, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0319.09

I cannot call them handsome — they were too pale and grave for the word […], like people consulting a dictionary to aid them in the task of translation. This scene was as silent as if all the figures had been shadows […], not one word was intelligible to me; for it was in an unknown tongue […]; it was only like a stroke of sounding brass to me — conveying no meaning […].

‘Is there ony country where they talk i’ that way?’ […]

‘Yes […] — a far larger country than England; where they talk in no other way.’

‘Well, for sure case, I knawn’t how they can understand t’ one t’ other: and if either o’ ye went there, ye could tell what they said, I guess?’

‘We could probably tell something of what they said, but not all’

C. Brontë, Jane Eyre1

Where meaning is many-faceted, language can become prismatic as easily as it can become crystal-clear — the meanings projected by one and the same form of words can splay into a spectrum of colour without loss of definition […]. The first question, then, would seem to be, not whether the poet can bring a prismatic splay of distinct meanings, but why he does it and why we like it.

W. Nowottny, The Language Poets Use2

Translations of Jane Eyre in Latin America and Spain: The Context of their First Widespread Impact in the 1940s

‘As far as I can see, it would be wiser and more judicious if you were to take to yourself the original at once’.3 Jane Eyre’s recommendation to St John could never have become the motto of Spanish and Latin American readers of British novels since the mid-nineteenth century. For them, for reasons that range from a constitutive relationship with the linguistic and cultural fabric making up the multiform literature and mestizo ethos of Latin America to what has been called modern Spain’s relative cultural dependency on its northern neighbours, translation has played and continues to play a decisive and inescapable role. Thus, it is not altogether surprising to find that an indirect Spanish version of Jane Eyre appeared in Santiago, Chile and Havana, Cuba, as early as 1850, i.e., only three years after the first edition of the English original, but also four decades before a first direct Spanish rendering appeared in New York (1889), and almost a century before several complete Spanish translations done directly from the English text began to have a widespread impact on both sides of the Atlantic from the 1940s onwards.4

Indeed, whereas translations of the novel up to the start of the Second World War can be counted on the fingers of one hand, from the early 1940s onwards there was a veritable burgeoning of versions and editions, both in Latin America, with particularly active centres in Buenos Aires (e.g., M. E. Antonini’s popular version for Acme Agency in 1941, marketed suggestively from 1944 onwards under a title that translates as Jane Eyre, Rebel Soul) and in Spain, with Barcelona clearly predominating over Madrid (e.g., J. G. de Luaces’ popular version for Iberia first published in 1943). Certainly, this proliferation of Jane Eyre translations can be explained in part by the renewed prestige acquired by English language and culture after the Second World War. But it started somewhat earlier, and can be put down as well, and especially, to differentiated local processes in the Latin American and Spanish contexts that led to the promotion of foreign literature generally and this English novel in particular. For whereas the translation boom that began in Spain in the early 1940s, in the face of censorship and abrupt stifling of local creative expression by the Franco dictatorship (1939–1975), can be understood as a literary compensation and even an implicit alibi serving to avoid oppression and write between the lines, not least in relation to the Francoist National-Catholic programme and the domestic role for women that it promoted, the Jane Eyre translation boom in Latin America was part of an explicit programme of opening up to and interacting with foreign languages and literatures as a way of creating a local ethos and literature emancipated from Spanish colonialism, especially in the young republics of the Southern Cone, where the novel became widely known at the very time the female vote and other civil rights for women were being secured.

As regards the context of reception in Spain, then, it should be recalled that Franco’s dictatorship not only began by abolishing a number of progressive reforms implemented by the previous Republican constitution, such as freedom of worship, equal rights between the sexes, and thence universal suffrage, but also set up a powerful and energetic system of censorship that directly impacted literary work and books, with side effects for translation. First of all, in what can be seen as a kind of sui generis reissuing of the Index librorum prohibitorum et derogatorum of the old Spanish Inquisition, Francoist censorship banned all kinds of works and authors seen as criticising the National-Catholic movement or threatening its orthodox imaginary, including not only pacifist, anti-fascist, Marxist, and separatist writings, but also theosophical and Masonic works, together with any dealing openly with sexual matters (whether scientific or otherwise) or including explicitly sexual scenes; in short, a whole array of works that, if encountered, were to be destroyed. Then, unpublished works had to undergo prior censorship before they could be published and distributed, to evaluate them in terms of respect for and compatibility with the ideology of the regime and dogmas of the Church, with verdicts that could range from the removal of certain passages to prohibition of the entire work. Thus, in a country where many of the leading women and men of literature, the arts, and the sciences had disappeared, either killed during the Civil War or forced into exile, among those who remained in Spain translation became not just a means of economic survival in extremely hard times, but also a possible way of exercising literary activity despite censorship, and even of establishing an alibi of anonymity that made it possible to write between the lines, dividing readerships into accomplices and dupes, creating complicity in resistance, a negative freedom by way of subtle gestures that made it impossible for the censors and other guardians of the law to arrive at forthright rulings. This partly explains the seeming paradox of a proliferation of translations amid the acute crisis of Spanish post-war economy, culture and literary production, with most of them being made from the European languages that the literati of the time were familiar with, and most particularly English (to the relative detriment of French and German, which had been dominant before the War), a proliferation that unsettled the guardians of orthodoxy on more than one occasion.5

As regards Latin America, the political and literary context in which translations and editions of Jane Eyre began to be multiplied and widely circulated was quite different. Certainly, the new relative predominance of English can be seen here as well, being further associated with the growing political power, influence, and intervention of the United States. But from the late 1930s to the late 1960s (i.e., before the era of North American-backed military dictatorships), the young republics of Latin America, independent of Spain for just over a century, embarked upon a period of relative industrial progress and new political, cultural, and literary awareness, where translation was often encouraged and understood explicitly as a necessary process in view of what Latin America’s literature and culture had been and ought to be, including as regards its emancipation and differentiation from Spain itself. This explicit awareness of translation as constitutive to the Latin American ethos can be traced from period to period and from north to south: at least as early as the reflections on the mestizo constitution which appear in the ambiguity of malinchism in Mexico (where a symbol of foundational linguistic and political betrayal of the native metamorphoses into a symbol of formative heterogeneity and female liberation from oppression),6 through the romantic republican project of the mid-nineteenth century (which sought to break away from the Spanish substratum and transform the language and culture of the southern countries by grafting other languages and cultures onto them),7 to the more recent conceptions of an anthropophagic relationship inspired by Amazonian culture (where what is posited is a relationship of capture, digestion, and assimilation of European, Oriental, and more broadly universal cultural strength in pursuit of local prowess).8 Amid this multiplicity of scenes — all very different, of course, and all complex in themselves and not without violence, but also evincing this common denominator of a constitutive translation experience — if the focus is narrowed to the River Plate context whence Jane Eyre was disseminated in the 1940s, it is worth considering Borges’ well-known admonitions in ‘The Argentine Writer and Tradition’ (1951), a good synecdoche for the simultaneously constitutive and emancipatory role explicitly assigned in the Southern Cone to the process of passing through the foreign. Activating his own sense of paradox, Borges reviews and rebuts three common claims about what literature and culture ought to be in Argentina and South America generally:

[1] The idea that Argentine poetry should abound in distinctive Argentine features and Argentine local colour seems to me a mistake […]. The Argentine cult of local colour is a recent European cult that nationalists should reject as foreign.

[2] It is said that there is a tradition to which we Argentine writers must adhere, and that tradition is Spanish literature […. But] Argentine history can be defined without inaccuracy as a desire for separation from Spain, as a voluntary distancing from Spain.

[3] This opinion is that we, the Argentines, are detached from the past […]. However […,] I believe that our tradition is the whole of Western culture, and I also believe that we have a right to this tradition, a greater right than the inhabitants of one or another Western nation may have […]. I believe that Argentines, South Americans in general, […] can deal with all European themes, deal with them without superstition, with an irreverence that may have, and is already having, happy consequences […]. And so I say again that we must be fearless and take the whole universe as our inheritance.9

Certainly, setting out from the paradoxical aesthetics of ‘originality as rewriting’ and ‘finis terrae cosmopolitanism’ that his particular vantage point on the River Plate allows him, Borges omits the dimension of conflict that has often been part of the translation experience in Latin America, ignoring the violence perpetrated on that which resists assimilation, as has often been the case with indigenous languages and cultures, while unilaterally emphasising the outlook of sceptical tolerance that a large-scale translation movement encourages. But Borges’ awareness of the extent to which South American literature and culture should be thought of as a journey through the foreign transcending any boundary between traditions and continents is characteristic of the women and men of letters of the Southern Cone, and particularly those of Buenos Aires (a city shaped by a succession of rapid and large-scale immigrations of Italians, Russians, Jews, Central Europeans, Asians, and others superadded to substrates of Spanish and indigenous descent), further resonating in this particular case on the cultural scene of the ‘translation machine’ that was Sur magazine, where Borges’ text was published.10 Since from the late 1930s onwards, everyone in South America who could translate did so; and everyone, whether they translated literature or not, understood each other through access to the foreign in translation, whether this meant intelligibility across the different languages that tend to be hastily grouped under the label of Latin American Spanish (themselves the product of different genealogies and translational emphases over the course of the particular history of each of their regions), or literary versions such as the ones from Jane Eyre that concern us here, which became accessible to a wide and varied readership extending far beyond the narrow circle of the polyglot elite to which someone like Borges himself belonged.

In this sense, as one moves from the general and differentiated outline of the contexts of reception in Spain and Latin America to the characteristics of the translations of Jane Eyre themselves in relation to their readerships, one can add that the more than thirty Spanish versions and hundreds of editions of the novel brought out since the 1940s on the two sides of the Atlantic reveal at least three different general approaches, manifested in decisions pertaining to both content and style, and driven by literary, commercial, and ideological constraints. That is, in what already constitutes a first, very general instance of literary and cultural prismatisation, one can distinguish between: (i) ‘relatively unabridged translations’, which preserve most of the literal surface of the novel, permitting a line-by-line comparison with the original; (ii) ‘edited compressed versions’, which often drop or merge sentences, cut passages and sometimes redistribute chapters, reducing the novel by up to half its length; and (iii) ‘highly condensed paraphrases’, which rewrite the novel as didactic material, reducing it to less than a third of its original length. While in each particular case it is possible to observe the extent to which excisions, as well as changes of style and content, are driven by considerations ranging from the ideological to the commercial, these three different, recurring approaches testify to a settled belief on the part of publishers that the novel could have just as much success as (i) a classic of world literature in the form of a female Bildungsroman, (ii) a romantic best-seller for the general public, or (iii) an edifying tale for the young.11

Finally, moving on from the foregoing introductory and contextual observations to the transcendental perspective on language that will determine many of the analyses to follow — i.e., to a point of view that interrogates linguistic and literary behaviour as the formal condition of possibility for the representation of reality and experience — it is worth clarifying that the aim in what follows is not to denounce the translative limits that the various modes of passage of Jane Eyre into Spanish reveal, but to evaluate the levels of refraction between the English and Spanish languages, literatures, and cultures arising in the process: the possibilities opened up or not by the formal insemination and the semantic afterlife involved in these different forms of translation, which, when strong and achieved, are capable both of changing modes of representation in the receiving language and of generating a backward effect on the original, unfolding its signification over time.

These formal inseminations and prismatisations can already be noticed to a certain degree at a stylistic micro-level, as can be seen in the next section (“The literary synthesis and representation of reality: evaluating the recreation of lexical, syntactic, musical, imagistic, and contextual forms of meaning”), while examining the variety of significant behaviours that the Spanish language takes on as it either echoes or, very often, departs from the English original lexicon, syntax, verbal music, verbal images or contextual forms of meaning, with the corresponding forms of experience and representation that they give rise to.

But it is above all while looking from a broader, contextual and cultural point of view on the impact of Jane Eyre in Latin America as compared to Spain (as we do in the subsequent two sections under the rubrics “Gender refractions: human individuality as feminist emancipation” and “Empire refractions: from savage slave to gothic ghost”), that one can see how the afterlife and refraction of the novel, starting with those of its crucial gender and colonial motifs, become particularly significant. Especially bearing in mind that Spanish-language versions of Jane Eyre became popular at a time when the women’s vote was being fought for and achieved in the newly independent Latin American republics, which had succeeded only a century earlier in shaking off the imperial yoke of Spain, where Franco’s National-Catholic programme was, during this same period, pursuing the restoration of so-called ‘traditional family values’.

The Literary Synthesis and Representation of Reality: Evaluating the Recreation of Lexical, Syntactic, Musical, Imagistic and Contextual Forms of Meaning

As one focuses on a comparative analysis of the ways the characteristic signifying behaviours of Charlotte Brontë’s English are rendered in the different Spanish translations — taking sample passages from the original that present distinctive organic textures to evaluate the difficulties encountered and the re-creations devised in the unabridged, compressed, and highly condensed versions — the aim is not to arrive at a value judgement of the quality of the translations or the translators, much the less to list blunders or significant losses relative to the original, but to evaluate prismatisation from a transcendental point of view, shedding light on the refractions arising out of these encounters between the English and Spanish languages, literatures, and cultures, and pointing to the possibilities of experience or literary representation they do or do not give rise to.

As a basis for the analyses that follow, we have selected seven of the most published and read translations of the last eighty years, produced for different readerships and purposes by translators situated differently in place, ideological stance, and time. To begin with, three unabridged translations (marked as ‘A’ alongside the translator’s name and date of publication in references below): (1) María Fernanda de Pereda’s 1947 Jane Eyre (Madrid: Aguilar, 780 pages, with at least fifteen editions since); (2) Carmen Martín Gaite’s 1999 Jane Eyre (Barcelona: Alba, 656 pages, with at least six editions since); and (3) Toni Hill’s 2009 Jane Eyre (Barcelona: Mondadori, 608 pages, with at least six editions since). Then, there are the two pioneering and most widely read compressed versions, published in Latin America and Spain just two years apart in the early forties (marked as ‘B’ alongside the translator’s name and date of publication in references below): (4) M. E. Antonini’s 1941 Jane Eyre (Buenos Aires: Acme Agency, 287 pages, with at least five editions in the next ten years as Jane Eyre, Alma Rebelde, and many more official editions and pirate versions since); and (5) Juan de Luaces’ 1943 Jane Eyre (Barcelona: Iberia-J. Gil, 518 pages, with at least thirty-five editions since). Lastly, the selection is completed by two highly condensed paraphrases for children, both of which rely heavily on Antonini’s earlier compressed version and have been published on both sides of the Atlantic over the years (marked as ‘C’ alongside the translator’s name and date of publication in references below): (6) Jesús Sánchez Díaz’s 1974 Jane Eyre (Santiago de Chile: Paulinas, 191 pages) and (7) Silvia Robles’ 1989 further condensed adaptation (Jane Eyre, Santiago de Chile: Zig Zag, 123 pages). Thus, while the selection concentrates on examples of the three different forms of passage into Spanish identified that have been repeatedly published and had large readerships, it also offers a broad spectrum as regards the individuality and positioning of the translators in the Spanish and Latin American contexts: from the Catalan Republican Juan de Luaces (tr. 1943), a promising writer and literary critic before the Civil War who, after a number of vicissitudes, including censorship and prison, became the most prolific of the post-war Spanish translators, to María Fernanda de Pereda (tr. 1947), who worked in close contact with the orthodox Madrid establishment; from M. E. Antonini (tr. 1941), who essentially translated adventure books for the young (Buffalo Bill, Robin Hood) for a popular collection issued by Acme Agency in Buenos Aires, to Jesús Sánchez Díaz (tr. 1974) in Spain, who translated mainly educational religious literature for the young for the Catholic publisher Ediciones Paulinas; from the very well-known prize-winning Spanish novelist Carmen Martín Gaite (tr. 1999), born in 1925 and associated with the Madrid literary world, to the psychologist and successful author of police novels Toni Hill (tr. 2009), born in Barcelona in 1966.12

In what concerns the sample passages highlighted below, the focus has been guided first and foremost by the characteristic elements of Brontë’s style in the English original, involving an examination of units of meaning from lexical networks and syntactic forms to the more sophisticated forms of verbal music, verbal imagery, and contextual effects (it being understood that many of these forms of representation overlap and work together), to analyse the way these have been re-created, dropped, or transformed in the different types of Spanish-language versions, with the corresponding impact on literary representation and experience.

Lexical Networks

To start with the most basic aspects, such as the taxonomy of reality produced by lexical networks, there are no drastic difficulties or prismatisations here, insofar as translation is facilitated by the partial overlap between the genealogies of the Spanish and English languages. Thus, most of the keywords that organise the world of the novel (passion, conscience, reason, feelings, resolve, nature, etc.) are translated in the unabridged editions by their usual Spanish synonyms or calques (pasión, consciencia, razón, sentimientos, resolución, naturaleza, etc.), with only some slight allusive refraction, mainly because of the differentiated impact of key concepts in Protestantism such as ‘conscience’, ‘reason’, and ‘resolve’ when it comes to describing female determination in the Latin American and Spanish contexts respectively.

Among the notable exceptions to this lexical straightforwardness are the twofold denotation and symbolism attached to the names that Brontë chooses for many of the characters and places in the novel: Burns, Reed, Temple, Rivers, Lowood, Thornfield. For, notwithstanding that the compressed versions and reduced paraphrases often adopt what was a common practice until the mid-twentieth century of Hispanicising names (as in Juana Eyre by Carlota Brontë), none of the Spanish versions sets out to account for this way in which Brontë charges the place-names with meaning. A partial exception in respect of Thornfield can be found in Luaces and Gaite, who resort to annotation. Thus, the latter, whose unabridged translation is the only one to provide systematic notes (more than a hundred in all), explains: ‘Thornfield significa “campo de espinos”. Con esta metáfora volverá a jugar más tarde’ [‘The name means ‘field of thorns’. The author will play on this metaphor again later’] (Gaite 1999A). Luaces, whose compressed edition provides only four footnotes, explains in the third of them: ‘Thornfield significa, literalmente, campo de espinos’ [‘The name literally means field of thorns’] (Luaces 1943B). Luaces will have nothing to say about the ‘fiery’ allusions of Burns or the ‘religious’ ones of Temple, however, which is perhaps already revealing of the kind of more-or-less automatic self-censorship that he applied under Franco’s dictatorship. For, as he tactically puts it in the prologue to his 1946 Spanish edition of The Canterbury Tales, dividing readerships into accomplices, innocents, and dupes: ‘I have resisted the itch to multiply footnotes. My contention is that the well-informed rarely need them and that they are of very limited value to the unlearned […]. In attempting to interpret and unpick all allusions and overtones, the annotator will often err and provide the reader in turn with a misleading picture.’13

Syntactic Forms

More dramatic are the transformations at a syntactic level, where forms characteristic of the novel, such as the direct presentation and detailed descriptions that reinforce testimonial and autobiographical experience, the syntactic repetitions and inversions that help to express altered states of mind and perception, and verbal time shifts used to convey emotion, are often simplified, creating a more straightforward texture and a more homogeneous, linear, logical, and distant representation of events.

In the first place, whereas the general style of the novel, although highly elaborate and reflexive, gives the impression of spontaneity — more precisely, whereas this fiction written as first person autobiography has a direct, almost epistolary style, often highly detailed in its descriptions, which allows things to be touched and felt — this is an aspect that is not only predictably curtailed in the compressed versions, and simply omitted in the condensed paraphrases, but also modified in the unabridged Spanish translations. Thus, a brief negative description such as ‘I know not what dress she had on: it was white and straight; but whether gown, sheet, or shroud, I cannot tell’,14 can become anything from a relatively literal ‘No sé cómo era su traje: si vestido, o manto, o mortaja; sólo distinguí que era blanco’ (Pereda 1947A),15 to a condensed version like ‘No me fijé cómo iba vestida; sólo sé que llevaba un traje blanco’ (Luaces, 1943B: ‘I did not pay attention to how she was dressed; I only know she had a white garment on’), to complete omission in Sánchez’s and Robles’ condensed paraphrases.

Secondly, while the novel’s syntax tends to be direct and relatively straightforward, something that heightens the naturalness and spontaneity of the tale and its emotions, confusion and excitement are often staged through parataxis, repetitions, and inversions. These ways of disrupting linear movement are often softened or transformed even in the unabridged Spanish-language versions, which tend to clarify and simplify, transforming such passages of fragmented, heightened, or confused perception into a more straightforward presentation. Take for instance the dramatic tension achieved in a passage describing Bertha’s night visit to Jane, who is still unaware of her existence:

I had risen up in bed, I bent forward: first surprise, then bewilderment, came over me; and then my blood crept cold through my veins. Mr. Rochester, this was not Sophie, it was not Leah, it was not Mrs. Fairfax: it was not — no, I was sure of it, and am still — it was not even that strange woman, Grace Poole.16

Confronted with these syntactic parataxes, inversions, and repetitions, even the unabridged versions, from Pereda (1947) to Gaite (1999), clarify the text, using resources such as logical connectives and explanation. Pereda gives:

Me incorporé en la cama y me incliné hacia adelante, sintiendo primero sorpresa, luego duda, y al darme cuenta de la realidad, la sangre se me heló en las venas. Señor Rochester, aquella mujer no era Sophie, ni Leah, ni la señora Fairfax, ni era, … de ello estoy absolutamente segura…, ni era siquiera esa mujer espeluznante que se llama Grace Poole.

(Pereda 1947A: ‘I sat up in the bed and [adds connective that avoids parataxis] leant forward, feeling [adds clarification and link that avoids parataxis] first surprise, then doubt, and as I became aware of the reality [interpolates a phrase to explain the confusion which in the original is staged by the behaviour of language], the blood froze in my veins. Mr. Rochester, that woman [introduces clarification] was not Sophie, nor Leah, nor Mrs. Fairfax, nor was it, … of this I am absolutely sure… [omits the time juxtaposition between past and present], it was not even that terrifying woman whose name is [introduces clarification] Grace Poole’.)17

The compressed versions provide similarly logic-oriented clarification; Antonini, for instance, while reducing the passage, explains: ‘y la sangre se heló en mis venas, porque la persona que estaba allí no era Sophia, ni la señora Fairfax, ni Lía, ni aun esa extraña Gracia Poole’ (Antonini 1941B: ‘and the blood froze in my veins, because the person who was there was not Sophie, nor Mrs Fairfax, nor Leah, nor even that strange Grace Poole’).18

Finally amid these syntactic characteristics, while Jane Eyre is narrated ex post facto by the protagonist, using the past tense to recount experiences which are over and done with and of which she knows the outcome, it often shifts to the present to express emotional tension, fading across from the point of view of Jane the narrator to the point of view of Jane the character to make us feel her emotions as they arise. Take for instance a passage that stages Jane’s tension when she sees Rochester flirting with Miss Ingram:

Miss Ingram placed herself at her leader’s right hand; the other diviners filled the chairs on each side of him and her. I did not now watch the actors; I no longer waited with interest for the curtain to rise; my attention was absorbed by the spectators; my eyes, erewhile fixed on the arch, were now irresistibly attracted to the semicircle of chairs… I see Mr. Rochester turn to Miss Ingram, and Miss Ingram to him; I see her incline her head towards him, till the jetty curls almost touch his shoulder and wave against his cheek; I hear their mutual whisperings; I recall their interchanged glances (my italics).19

These shifts of verbal tense into the present to express emotional tension in the current scene, as in the second half of the excerpt, are re-created by Pereda’s unabridged Spanish translation and especially by those of Gaite and Hill.20 Luaces’ condensed version, however, unifies the point of view by keeping all verbs in the past (Antonini and Sánchez cut the whole scene). Luaces renders it:

Miss Ingram se colocó al lado de Rochester. Los demás, en sillas inmediatas, a ambos lados de ellos. Yo dejé de mirar a los actores; había perdido todo interés por los acertijos y, en cambio, mis ojos se sentían irresistiblemente atraídos por el círculo de espectadores… Ví a Mr. Rochester inclinarse hacia Blanche para consultarla y a ella acercarse a él hasta que los rizos de la joven casi tocaban los hombros y las mejillas de sus compañeros. Yo escuchaba sus cuchicheos y notaba las miradas que cambiaban entre sí (Luaces 1943B; my italics).21

The original fade-out from the narration in the present to the intensity of the past emotion, produced by the change in verbal tense, is thus unified in a single viewpoint, a texture without time inflections, where what does stand out though is the vividness of Luaces’ onomatopoeias (‘escuchaba sus cuchicheos’), conveying a musicality which he is often more alert to and re-creates more effectively than the other Spanish translators being considered.

Verbal Music

Even as the Spanish renderings of Jane Eyre tend to simplify the syntax, they also, more often than not, do not recreate the verbal music, at least locally. There are some variously prominent exceptions in Pereda, Gaite, and Hill when the musicality of the original passages themselves is particularly significant; thus, ‘the west wind whispered in the ivy’22 becomes ‘El viento susurraba entre las hojas de hiedra’ (Pereda 1947A); similarly, and more sustainedly, ‘A waft of wind came sweeping down the laurel-walk […]: it wandered away — away to an indefinite distance — it died’23 is rendered in a way that re-creates the harder consonance: ‘El viento pasó deprisa por nuestro sendero […], y fue a extinguirse lejos, muy lejos […] a infinita distancia de donde estábamos’ (Pereda 1947A); or ‘Una racha imprevista de viento vino a barrer el camino de los laureles […]. Luego se alejó hasta morir lejos’ (Gaite 1999A); lastly, lines from songs such as ‘Like heather that, in the wilderness, / The wild wind whirls away’24 are rendered in a way that retains the consonance (but not the clear vowel sounds): ‘Como el brezo, arrancado del bosque / por una ráfaga de viento salvaje’ (Hill 2009A).25 But the sound iconicity of the original is usually disregarded, even in very noticeable instances similar to those quoted above, especially when it comes to the hard alliteration and the staccato effect that the predominance of monosyllables in the English language is able to create, and that can be very effective at staging extreme emotions, as in: ‘Up the blood rushed to his face; forth flashed the fire from his eyes […]. “Farewell, for ever!”’,26 a musicality that is hard to re-create given the general sonority of Spanish, with its predominance of polysyllables, its more spaced-out accentuation and its legato sounds.

In this sense, even concerning a unique sound effect of Brontë’s in Jane Eyre, namely her play on the ‘eir’ sound in words such as ‘dare’, ‘rare’, ‘err’, and many others to make the name of the protagonist resonate by homophony, the Spanish translators devise no way of re-creating it, with the partial exception of Luaces. Take a particularly emphatic use of the resource in Chapter 35: the dreamlike state in which Jane hears Rochester’s voice calling her, where the sound-play makes her name echo time and again from beyond the immediacy of the scene and the linearity of the prose:

I might have said, ‘Where is it?’ for it did not seem in the room — nor in the house — nor in the garden; it did not come out of the air — nor from under the earth — nor from overhead. I had heard it — where, or whence, forever impossible to know! And it was the voice of a human being — a known, loved, well-remembered voice — that of Edward Fairfax Rochester; and it spoke in pain and woe, wildly, eerily, urgently.27

The ghostly sounds of the homophonies and half-homophonies contributing to the sensuous feeling of the scene, with ‘where’, ‘air’, ‘earth’, ‘heard’, ‘eerily’, ‘urgently’, and other words making us hear how Jane ‘Eyre’ is being called by name even before the language of the novel literally tells us so, are not easy to re-create in Spanish. Thus, none of the translators even of the unabridged versions attempted to stage the effect locally, and it is possible that they were unaware of it. Luaces, though, who was certainly aware of the sound pattern, devised a partial and indirect way of conveying its import to the reader in his condensed version, writing:

En vez de qué, debía haber preguntado dónde, porque ciertamente no sonaba ni en el cuarto, ni encima de mí. Y sin embargo era una voz, una voz inconfundible, una voz adorada, la voz de Edward Fairfax Rochester, hablando con una expresión de agonía y dolor infinitos, penetrantes, urgentes.

(Luaces 1943B: ‘Instead of what, I should have asked where, for certainly it came neither from the bedroom, nor from above me. And yet it was a voice, an unmistakable voice, a beloved voice, Edward Fairfax Rochester’s voice, speaking with an expression of infinite, penetrating and urgent agony and pain’.)

By repeating the word ‘voice’ several times, Luaces takes what the homophonies of the original do between the lines and repeatedly and explicitly says it in the Spanish-language version, laying out in literal terms the fact that Jane is being called insistently.

Verbal Images

It is as one moves on to the translation of verbal images, which are usually easier to reproduce in another language than syntax, music, or contextual effects, that one finds a more sustained and massive re-creation in Spanish of Brontë’s idiosyncratic forms of representation and experience. This can be observed not only in the networks of metaphors and the corresponding analogical presentation of feelings, entities, and events, but also in the biblically inspired parallelistic forms promoting correlative presentation and, less frequently, in the perspectivism on reality activated by the paratactic superposition of points of view, all of which have a decisive impact on the way the representation of reality is topologically organized.

In general, as might be expected, metaphorical patterns and other classical tropes reappear in Spanish even when the translator is not being particularly re-creative, as does their effect of dualistic representation of the real, which analogically relates the dispersion of the sensible comparison to the ideal meaning that unifies it. Thus, for instance, the whole panoply of well-worn metaphors drawing on an imaginary of war or slavery to represent the ‘conquests’ and ‘submissions’ of love — ‘Jane: you please me, and you master me — you seem to submit, and I like the sense of pliancy you impart; and while I am twining the soft, silken skein round my finger, it sends a thrill up my arm to my heart. I am influenced — conquered; and the influence is sweeter than I can express; and the conquest I undergo has a witchery beyond any triumph I can win’28 — are re-created relatively automatically, with few omissions or transformations in the unabridged Spanish translations, omnipresent as these metaphors are in the so-called Western tradition and European languages.29 Because of this largely shared background, even the symbols of the novel tend to remain quite stable (less so the personifications of faculties such as Reason, Memory, etc., which describe Jane’s inner conflict and growing spirituality in a Protestant ethos).

Among the composite figurations characteristic of the novel that are actively re-created by Spanish-language translators, mention must be made of biblically inspired semantic parallelism, a form of representation by repetition or correlation of complementary entities that Charlotte Brontë will have imbibed naturally from the Scriptures and from the sermons she heard from her minister father, projecting a correlative topology of the real.30 Such parallelisms often appear when biblical passages are quoted verbatim in the novel: ‘Better is a dinner of herbs where love is, [/] than a stalled ox and hatred therewith’.31 But Brontë also uses parallelism as a literary device when she wants to express extreme emotion, changes of fortune suffered by the protagonist, and other tensions suited to a correlative or contrasted representation of reality. Thus, at the beginning of the novel, parallelism is activated in Jane’s emotional description of her confinement in the red room: ‘This room was chill, because it seldom had a fire; [/] it was silent, because remote from the nursery and kitchens’.32 Again, later in the novel, it determines the way she describes the lonely pathway on which she first meets Rochester: ‘The ground was hard, [/] the air was still […]. [//] I walked fast till I got warm, [/] and then I walked slowly to enjoy […] [//] the charm of the hour lay in its approaching dimness, [/] in the low-gliding and pale-beaming sun’.33 An even more emphatic example can be found towards the end of the novel, as she describes her definitive change of destiny after meeting Rochester again: ‘Sacrifice! [/] What do I sacrifice? [//] Famine for food, [/] expectation for content. [//] To be privileged to put my arms round what I value — [/] to press my lips to what I love’.34

Unquestionably, the passage most continuously shaped by these forms of biblically inspired parallelism, oscillating between the repetition and the complementation of an idea through its correlative, is found in the last pages of Chapter 26, where the stylistic device serves to express the contrasts in Jane’s change of fortune and the extreme emotion with which she contemplates the cancellation of her marriage with Rochester. This very long passage, written in parallel prose throughout, opens:

Jane Eyre, who had been an ardent, expectant woman — almost a bride —, [/] was a cold, solitary girl again: [//] her life was pale; [/] her prospects were desolate. [//] A Christmas frost had come at midsummer; [/] a white December storm had whirled over June; [//] ice glazed the ripe apples, [/] drifts crushed the blowing roses; [//] on hayfield and cornfield lay a frozen shroud: [/] lanes which last night blushed full of flowers, to-day were pathless with untrodden snow.

After some thirty more lines in a similar vein, this extended passage in parallel prose ends by flowing into the actual words of Psalm 69:

The whole consciousness of my life lorn, my love lost, [/] my hope quenched, my faith death-struck, [/] swayed full and mighty above me in one sullen mass. [/] That bitter hour cannot be described: [/] in truth, ‘the waters came into my soul; I sank in deep mire: [/] I felt no standing; I came into deep waters; the floods overflowed me’.35

Of the unabridged Spanish translations, both Gaite’s and Hill’s re-create most of the parallelistic form of presentation, with the corresponding representation of reality as contrast and correlation of entities, events, and experiences.36 Pereda, for her part, somewhat relaxes the effect by using, as she tends to do, illative words and other particles that soften the predominantly binary parataxis, while preserving something of the parallel style of representation in the passage as a whole; she further ends with a dissolve, omitting the quotation marks around the biblical passage.37 As for the condensed literary versions, Antonini reduces the passage to little more than a quarter of its original length, dissolving most of the biblically-inspired parallelism, including the quotation at the end. Luaces, though, while condensing, maintains the parallelistic figuration of entities and feelings throughout the passage — ‘Mis esperanzas habían muerto de repente; [/] mis deseos, el día anterior rebosantes de vida, estaban convertidos en lívidos cadáveres… [//] Cerré los ojos. [/] La oscuridad me rodeó’ (Luaces 1943B) — highlighting the verbatim intrusion of the Psalms at the end by using quotation marks, just as the English original does: ‘La conciencia de mi vida rota, de mi amor perdido, de mi esperanza deshecha, me abrumó como una inmensa masa. Imposible describir la amargura de aquel momento. Bien puede decirse que “las olas inundaron mi alma, me sentí hundir en el légamo, [/] en el seno de las aguas profundas, y las ondas pasaron sobre mi cabeza”’ (Luaces 1943B).

Less re-creation and more simplification are to be found in the renderings of complex images formed by the paratactic juxtaposition of points of view, a perspectivism capable of providing a kaleidoscopic experience. Indeed, other than in quite limited instances, moments of kaleidoscopic perspectivism are dissolved into a more homogenous texture in the Spanish, even into a single point of view, with the resultant simplification of space-time representation.

A limited form of perspectivism is often constructed by the narrator’s voice addressing the reader of the novel — ‘oh, romantic reader, forgive me for telling the plain truth!’38 — juxtaposing the space-time of the fictitious Jane as a very self-conscious narrator, the space-time of the story itself with Jane as a character, and the space-time of the empirical reader, which is multiple and changeable over time. These forms of superposition, which can be used to create complicity and allow the narrator to impose her preferences and better control the reader’s reactions, offer no difficulty and are for the most part re-created in the unabridged Spanish-language translations — ‘perdona, lector romántico, que te diga la verdad escueta’ (Pereda 1947A), ‘oh, lector romántico, perdóname por contarte la verdad sin adornos’ (Hill, 2009A), less literally in ‘perdona, lector, si te parece poco romántico, pero la verdad es que…’ (Gaite 1999A) — as they are about two thirds of the time in Luaces’ condensed version, including as it happens in this particular instance: ‘perdona, lector romántico, que te diga la verdad desnuda’ (Luaces 1943B).39

The same can be said of the limited perspectivism obtained by the juxtaposition of linguistic planes, interrupting the unity of the English language. This can be seen very obviously in the intrusion of foreign tongues, such as Miss Temple’s Latin, Diana and Mary River’s German and Blanche Ingram’s Italian, with the most sustained instance being Adèle’s French — ‘having replied to her “Revenez bientôt, ma bonne amie, ma chère Mdlle. Jeannette,” with a kiss, I set out’40 — which serves to outline the girl’s character, but also to create complicity with the reader through the traditional nineteenth-century education shared by the ‘highly educated’ (thus, French is also used occasionally by Jane the character, who learned it at Lowood, as well as by Rochester and the friends he receives at Thornfield).41 Pereda and Hill’s un-abridged translations almost always re-create these juxtapositions of linguistic planes — ‘y contestando con un beso a sus frases cariñosas de Revenez bientôt, ma bonne amie, ma chère mademoiselle Jeannette, salí de casa y me puse en camino’ (Pereda 1947A), ‘respondí con un beso a su despedida, “Revenez bientôt ma bonne amie, ma chère mlle. Jeannette”, y salí de la casa’ (Hill 2009A) — while Gaite also adds notes giving the Spanish translation of the French in the text: ‘Revenez bientôt, ma bonne amie, ma chère mademoiselle Jeannette [Note: Vuelva pronto, mi buena amiga, mi querida señorita Jeannette].’ Le contesté con un beso, y salí’ (Gaite 1999A). Not so the condensed versions, however, where even Luaces, at least when it comes to Adèle’s French, homogenizes to a single Spanish perspective in all but a couple of cases, giving in this instance: ‘respondí con un beso a su “Vuelva pronto, mi buena amiga Miss Jane”, y emprendí la marcha’ (Luaces 1943B). They are likewise omitted from Antonini’s version and predictably in the reduced paraphrases, produced as they were with young readers in mind. This same unification of linguistic planes is also found in all the different kinds of Spanish versions when they come to deal with the linguistic perspectivisms produced by the juxtaposition of different English registers, such as John’s local form of speech — ‘You’re noan so far fro’ Thornfield now’42 — or Hannah’s — ‘Some does one thing, and some another. Poor folk mun get on as they can’43 — which are dissolved into the general texture in all the different kinds of Spanish versions.

Leaving aside these simple and limited cases of addresses to the reader and inclusion of foreign languages or local registers, a more frequent and complex form of perspectivism in the novel is created by the juxtaposition without transition of points of view such as direct and indirect address, present and past tense, narration, and dialogue, etc., creating an almost kaleidoscopic presentation of reality with great dramatic potential. Take Jane’s account of Bertha’s nocturnal visit before the cancelled wedding (in which Jane-the-character in the past is already taking the place of Jane-the-narrator in the present). It begins:

All the preface, sir; the tale is yet to come [a literary register — preface, tale — in the present which announces the future to narrate the past]. On waking, a gleam dazzled my eyes; I thought — Oh, it is daylight! [direct account of her thoughts in the past, staged in the present tense; but then back to the narration:] But I was mistaken; it was only candlelight. Sophie, I supposed, had come in. There was a light on the dressing-table, and the door of the closet, where, before going to bed, I had hung my wedding-dress and veil, stood open [introduction of pluperfect time, and then back to past:]; I heard a rustling there. I asked, ‘Sophie, what are you doing?’ [new change to her voice in the past staged in the present tense, and then back to the narration:] No one answered; but a form emerged from the closet.44

Even among the unabridged translations, only Gaite keeps the general juxtaposition of points of view,45 while Pereda and Hill reduce the perspectivism, dissolving some of the dramatic intensity by cutting out references in the future and pluperfect tense as well as some direct accounts of Jane’s thoughts in the past.46 Something similar can be observed in Luaces’ condensed version,47 while in Antonini and the two reduced paraphrases the passage is fused with Jane’s earlier dream as a continuation of it, omitting all reference to the prologue and unifying them into a single perspective.48 Most of the English perspectivism is thus transformed into a single point of view, a kind of counter-prismatisation that unifies the juxtaposition of time and narrative forms of indirect and direct presentation into a sort of omniscient narrative voice, no longer confronting us with the drama inside the protagonist as a kaleidoscopic consciousness.

Contextual Effects

Turning finally to contextual effects, to those forms of language that generate meaning and project representation by appealing to and playing with the reader’s expectations within a certain historical and literary context (such as allusion, connotation, irony, intertextuality, etc.), the enormous difficulties they impose on the re-creative task of a literary translator who wants to keep meaning under control are increased when the new text is to be read in more than one context, as was often the case with the Spanish versions of Jane Eyre in the second half of the twentieth century. In principle, confronted with the variously noticeable change of linguistic, literary, cultural, and epochal contexts between Victorian England and twentieth-century Spanish-speaking countries, preserving the effect of allusions, intertextuality, or other contextual forms of meaning (such as political preferences conveyed through literary allusion to the traditional canon or defiance of religious authority conveyed by intertextuality), would often involve creating new equivalent events capable of activating these effects by reference to the new context, including new representatives of the approved literary, political or religious law — an effort at re-creation that is not found in a sustained way in the Spanish-language versions of Jane Eyre (or in commercial literary translation of novels into Spanish generally in contemporary times). Moreover, one must be aware that, owing to the significant differences between the literary and political contexts of reception during most of the twentieth century in Latin America as compared to Spain, the same factual translation of Jane Eyre could generate different overtones on either side of the Atlantic, an added difficulty which resulted, not in strong re-creation, but in calculations and self-censorship of various kinds, especially among the translators working within the context of Franco’s dictatorship, and, in any case and often, in strong forms of refraction.

Certainly, most Spanish versions manage, more or less automatically, to activate some of the original meanings that depend on a relatively shared context, which existed for most of the twentieth century. This is the case with a significant number of the biblical allusions in the novel, for instance, which tend to preserve their effect when the translators maintain them as such. The same is true of the many proverbial expressions — ‘Beauty is in the eye of the beholder’, ‘All is not gold that glitters’, ‘To each villain his own vice’49 — often activated by naturally arising Spanish-language proverbial equivalents: ‘La belleza está en los ojos del que mira’ (Luaces 1943B); ‘La belleza está en los ojos de aquel que mira’ (Gaite 1999A); ‘No es oro todo lo que reluce’ (Luaces 1943B, Pereda 1947A, Gaite 1999A, Hill 2009A); ‘A cada vicioso con su vicio’ (Pereda 1947A), ‘Cada villano tiene su vicio’ (Gaite 1999A). Even some of the religious-political allusions in the context of the relationship and tension between the Anglican and Catholic churches can reappear more or less spontaneously, or when annotated and literalised; thus, a reference such as the one in Chapter 3 to Guy Fawkes — ‘Abbot, I think, gave me credit for being a sort of infantile Guy Fawkes’ — who was known as Guido Fawkes when he fought with the Spanish army, can be maintained and work as such, both in Luaces’ condensed version (1943) and Hill’s unabridged version (2009) (Gaite also keeps it, telling the reader in a note that he was a ‘conspirator in the time of James I in England, in the early seventeenth century’ (Gaite 1999A)). Pereda literalises the meaning of the reference by using the word ‘conspiradora’ (‘conspirator’) instead of the proper name, while Antonini is more creative, refracting the reference as: ‘Creo que para la Abbot era yo una especie de bruja infantil’ (Antonini 1941B: ‘I think that for Abbot I was a kind of child witch’)). The same re-creation can be found in the case of meaningful contrasts such as the one between ‘stylish’ and ‘puritanical’ in Chapter 20, with both erotic and religious harmonics — ‘The hue of her dress was black too; but its fashion was so different from her sister’s — so much more flowing and becoming — it looked as stylish as the other’s looked puritanical’ — which quite naturally maintains its effectiveness in the Spanish tradition, where these connotations of puritanism, including the use of the adjectival form of the word as a well-worn image in opposition to the sensual, are well established. Thus, Antonini’s condensed version published in Argentina gives: ‘Vestía también de negro como su hermana, pero no en estilo puritano sino elegante’ (Antonini 1941B); while an orthodox establishment figure such as Pereda can allow herself to render it: ‘Vestía también de negro, pero con un traje tan estilizado y tan a la moda como lo era el de su hermana sencillo y puritano’ (Pereda 1947A). But someone like Luaces, a Republican translating in the immediate aftermath of the Spanish Civil War, avoids murky religious waters and omits all reference to puritanism, especially its contrast to the sensual, rendering the sentence: ‘Su vestido era negro también, pero absolutamente distinto al de su hermana. Una especie de luto estilizado’ (Luaces 1943B: ‘Her dress was black too, but completely different to her sister’s. A kind of stylised mourning.’) Gaite, lastly, translating half a century later, in post-Franco times, allows herself to unpack and strongly emphasise the implications of the strict parallelism in the original: ‘También iba de luto, pero su vestido, ceñido y a la moda, no llamaba la atención precisamente por su puritanismo como el de la hermana’ (Gaite 1999A: ‘She wore mourning too, but her dress, close-fitting and fashionable, was not exactly remarkable for its puritanism like her sister’s.’).50

Aside from these instances of more or less automatic reactivation when the references are not cut out, most of the contextual forms of meaning either dissolve or refract in more unpredictable directions in the Spanish-language versions, which do not establish new references to activate the same effects in the context of the new culture. Nor do they use sustained annotation, with the notable exception of Gaite’s translation, which has more than a hundred notes clarifying historical and geographical references, mythological, biblical, and literary allusions, and even some possible ironies; in sum, informing the modern Spanish reader of what the contextual literary forms of meaning of the original would make complicit English readers experience directly.51

Thus, where the linguistic-literary context is concerned, these forms of meaning can be seen predictably to disappear when they depend on intertextuality with earlier works of English literature, or with books fashionable at the time, since the prodigious web of textual allusion in the original, whether retained or not, does not activate easily in the Spanish context of reception (and the same probably holds true for most contemporary English readers, as the increasing annotation in current commercial editions suggests). These instances range from references to classics such as Bunyan, Shakespeare, Milton, Johnson, Swift, Burns, Richardson, Byron, Scott, Keats, and others, up to the works that Jane reads during her formative years: the childhood vision of exotic faraway sea coasts obtained from Bewick’s History of British Birds (Chapter 1), or even the exotic stories of the ‘Arabian Tales’ (Chapter 2) (which some of the translators do not seem to realise are The Arabian Nights, known in Spanish as Las mil y una noches — The Thousand and One Nights). Even when very obvious references crop up in the original English, such as an interpolation taken from one of Shakespeare’s best-known works in the conversation between Mrs Fairfax and Jane after her arrival at Thornfield, while they are touching with ominous humour the possible presence of ghosts in the house — ‘Yes — “after life’s fitful fever they sleep well [Macbeth 3.2.23],” I muttered’ — the effect is mostly lost.52 A partial exception is Gaite, who translates in high tone: ‘“Sí — murmuré yo — tras la fiebre caprichosa de la vida, duerme plácidamente”’ (‘“Yes, — I muttered —, after life’s fitful fever, he sleeps peacefully”’), and who adds a footnote explaining the reference, as she does for other contextual aspects: ‘Charlotte Brontë liked to display her knowledge of literature. This is a phrase from act III of Shakespeare’s Macbeth and refers to the King of Scotland, Duncan, whom he has recently murdered’ (Gaite 1999A).53 But in the other editions, whether the inverted commas and attendant superposition of planes are preserved as they stand, as in Hill’s unabridged version — ‘Sí. “Tras la intensa fiebre de la vida llega el reposo más plácido” — murmuré’ (Hill 2009A) — or are done away with, so that these appear to be Jane’s own words — ‘Sí, después de una vida borrascosa bueno es dormir — murmuré’ (Antonini 1941B), ‘Hartos de turbulencia, reposan tranquilos, ¿no? — comenté’ (Luaces 1943B), ‘Claro; duermen en paz después de una vida de emociones y de agitación — murmuré’ (Pereda 1947A) — the effect of intertextuality is diluted and the ominous parallelisms with Duncan’s death, or more broadly with the ghosts and events of Macbeth as a whole, are not activated.

Generally speaking, whether or not all the individual translators were familiar with these and other less well-known passages of English literature, they tended to submit to the current imperative in commercial editions of prioritising the plot of the story without ‘distractions’ for the Spanish-speaking reader, removing — or at least not re-creating via new references — the allusions and other effects of intertextual forms. Thus, whereas in the original context this whole web of literary allusion was able to divide readers between those who noticed it and extract its meaning and those who did not (starting with the significant fact that literary allusion is as important in Jane Eyre as biblical allusion, with both being placed at the same level of importance in the protagonist’s development and generating a potential complicity with the novel’s readership in this respect), in the Spanish translations, where they are not simply done away with — as they often are in the compressed versions and almost always are in the condensed paraphrases — their literal preservation, without any re-creative effort to reflect the difference in context and literary expectations, means they are left adrift like messages in a bottle.

Where the historical context is concerned, however, there is a much greater tendency towards refraction in the transition from Victorian England to post-Second World War Spain and Latin America. This can already be seen in the case of religious references and their moral and political overtones, which are capable of generating a renewed meaning when transposed from Protestant England to Catholic Spain, leading some translators to variously emphatic self-censure and writing between the lines, especially if they were working under Franco’s censorship and programme to restore traditional National-Catholic values (Spain remained a confessional state until 1978).

In general terms, Charlotte Brontë had no particular liking for the Roman Catholic form of Christianity, dominant in Spain and Latin America, or for rigid Pharisaic forms of Protestantism and Anglicanism. ‘I consider Methodism, Quakerism, and the extremes of High and Low Churchism foolish, but Roman Catholicism beats them all’,54 she wrote some time after publishing Jane Eyre, a statement that helps to unfold her true intentions behind some of the religious references and overtones in her novel. For the effect even of the English original in the context of the religious conventions of Victorian England was felt to be discordant and was attacked as anti-Christian, prompting Brontë to mount a tactical defence; as she summarises it in a well-known passage of her Prologue to the Second Edition (1848): ‘Having thus acknowledged what I owe those who have aided and approved me, I turn to another class […] I mean the timorous or carping few who doubt the tendency of such books as ‘Jane Eyre:’ in whose eyes whatever is unusual is wrong; whose ears detect in each protest against bigotry — that parent of crime — an insult to piety, that regent of God on earth. I would suggest to such doubters certain obvious distinctions […]. Conventionality is not morality. Self-righteousness is not religion. To attack the first is not to assail the last. To pluck the mask from the face of the Pharisee, is not to lift an impious hand to the Crown of Thorns.’

Symptomatically, of the seven versions being considered here, only Gaite’s translation, done in 1999 from the second English edition, reproduces Brontë’s Preface. More broadly, when confronted with religious references, especially with dissident overtones, one often finds either transformation or self-censorship according to the religious orthodoxy or the position of the translator relative to the political regime and apparatus of censorship in the new Spanish context.

Take the different ways of translating a passage such as Jane’s ‘innocent’ and ‘spontaneous’ words when she is faced with Helen’s imminent death: ‘How sad to be lying now on a sick bed, and to be in danger of dying! This world is pleasant — it would be dreary to be called from it, and to have to go who knows where?’.55 Pereda, as one would expect, reconciles the anxiety about death with orthodox Catholic dogma, making Jane doubt the exact location but not the existence of the realm of the dead: ‘¡Qué triste debe de ser verse tendido en una cama y en peligro de muerte, con lo hermoso que es el mundo! ¡Será espantoso dejarlo para ir a un lugar desconocido que no se sabe en dónde está [go to a place whose whereabouts are unknown]!’ (Pereda, 1947A). Luaces, a Republican, accentuates between the lines, using a religious expression (God knows where) to subvert religion; stressing the subversion of consolation vis-à-vis death, he renders it: ‘¡Qué triste estar enfermo, en peligro de muerte! El mundo es hermoso. ¡Qué terrible debe ser que le arrebaten a uno de él para ir a parar Dios sabe dónde [to end up God knows where]!’, a passage whose rendering acquires further political overtones from the fact that it was published just a few years after the massacres of the Spanish Civil War.

Conversely, a revealing example of the removal of allusive references can be found in the treatment of the interpolation of Esther 5.3 in Chapter 24 — ‘Now, King Ahasuerus! What do I want with half your estate? Do you think I am a Jew-usurer, seeking good investment in land?’ — which takes on a particularly ominous meaning in the years after the Spanish Civil War and the Second World War. Once again, the positions of these two Spanish translators working in the forties are symptomatic. Thus, whereas Pereda keeps this intact in her translation, just as she does other biblical allusions — ‘Bueno, rey Asuero. ¿Para qué necesito yo la mitad de su hacienda? ¿Es que se figura que soy un judío usurero que voy buscando la manera de sacar partido de unos caudales?’ (Pereda 1947A) — Luaces cuts out the entire reference (as does Antonini in Argentina at the same time, by contrast with the more recent versions, which are more literal here).56

Finally, in less conscious but no less revealing modes, one can consider the way the turn of phrase ‘my master’ is avoided by Luaces and the rest of the early Spanish translators when used by Jane for Rochester (while this same word ‘master’ is kept as ‘maestro’ when confined to its social and educational uses). That is, confronted with expressions such as ‘“It must have been one of them,” interrupted my master’,57 whereas Antonini in Argentina (1941) or Hill much later in Spain (2009) would often render the expression as ‘mi señor’, with clear erotic overtones, none of the early versions published in Spain offer this turn of phrase ‘mi señor’, using rather expressions such as ‘Rochester’ (Luaces 1943) or ‘el señor Rochester’ (‘mister Rochester’: Pereda 1947, as well as later in Sánchez 1974). For despite a possible literal reading (Jane was in fact employed by Rochester), the immediate literal equivalent of ‘my master’ as ‘mi señor’ would have had disruptive religious overtones in mid-century Spain, being normally reserved in the Spanish language and Catholic tradition for Christ who, according to his biographers in the Gospels, was already thus called by his disciples: master. In synthesis, it would be giving to a man what belongs to God.

One can realize how in two of the three instances just examined, as in other examples commented on before, Luaces takes advantage of the cover of anonymity provided by his position as translator to write episodically between the lines, shielded as he is by the canonical authority of Charlotte Brontë, whom he recalls in the brief introductory note to his Spanish edition is one of the greatest women writers of all time, concluding, no less surreptitiously in the context of the immediate situation in Spain, that ‘Jane Eyre is, in summary, a bright picture on a dark background’ (Luaces 1943B). But this is a way of dividing readerships between accomplices and dupes that Luaces only activates occasionally, when opportunity allows or the passage merits it, while he acts cautiously and censors himself in many other instances when it comes to translating religious or social references with local harmonics, since out of political considerations and the need to earn a living he could not risk his manuscripts being rejected by the censor (something he was familiar with, since his text Fuera de su sitio was banned in 1939, probably because of its open treatment of sexual matters).58 Luaces’ duplicity was effective, in any event, and the guardians of the law took the bait; in its prior censorship ruling, the Department of Propaganda decreed (13 October 1942) that Jane Eyre was ‘A good novel that tells the life story of an orphan girl, her sufferings and her struggle to attain to a decent living. It is completely moral, but because it is an English work, all its action takes place within the Protestant religion,’59 in view of which nothing was required to be removed or altered, it being considered that these dissonances characteristic of the Protestant religion had been duly toned down and transformed (which is indeed the case with other additional aspects, such as the harsh and punitive Calvinist God, or the evangelism of St John Rivers, which are played down, not to mention occasional allusions to non-Christian religions, which Luaces simply removes).

Nonetheless, despite Luaces’ self-censorship and transformations by other translators, dissident or otherwise, to avoid problems with the guardians of the law, the difference in cultural and historical horizon between Victorian England and post-war Spain and Latin America could not but produce a sharp refraction of the contextual effects in Jane Eyre. Leaving aside all explicit self-conscious censorship to dupe the guardians of the law, and to a more acute degree than with the recreations and refractions in lexical, grammatical, musical, and imagistic aspects reviewed earlier, it is mainly when these contextual effects come to be evaluated that one finds a sharp prismatisation of the work in the Spanish language. And of these refractions between the different cultural contexts, it is above all the prismatisations concerning gender and colonial motifs in the new differentiated contexts of the Latin American republics as compared to Spain under Franco’s dictatorship which become particularly significant, as will be examined in the two sections that follow.

Gender Refractions: Human Individuality as Feminist Emancipation

Among the cultural instances that refract most decisively in the passage of Jane Eyre from its original context of inscription in mid-nineteenth century Victorian England to the mid-twentieth century contexts in which its Spanish translations were popularized in Latin America and Spain, one finds first and foremost its potential as a feminist emancipation manifesto. For, even beyond the different levels of emphasis or self-censorship that can be found in the translations, whether emphasizing or downplaying the protagonist’s passion and sense of independence, the very sense of individuality congenial to Protestant English culture, key to the pathos and plot of this kind of Bildungsroman presentation of a female character’s development against adversity, is refracted in decisive and differentiated ways in the young republics of South America, on the one hand, where struggles for the women’s vote and other civil rights were in their critical stages, and in the Iberian Peninsula, on the other, where Franco’s National-Catholic programme sought to re-establish traditional family values that assigned women a domestic role.

Certainly, the force of the novel as a provocative statement about women’s emancipation can easily be lost on contemporary Spanish readers (or indeed English ones) — they might be confused, for instance, by the way Jane, despite her disdain for John Reed or for St John Rivers’ ambitions, seems to aspire to marriage as a woman’s ultimate fulfilment — so that contextual adjustments are required to take the full measure of its original impact and likewise its potential for refraction in mid-twentieth century translations in Latin America and Spain. Regarding the English text in its original context of inscription, the reader must be reminded that this mid-nineteenth century portrait of the desires and frustrations of an educated woman not enjoying all the privileges of class, written at a time when women had few civil rights, was experienced by its Victorian readership as depicting an impetuous, rebellious figure who broke the traditional moulds and was described as ‘unfeminine’ by her detractors (within and outside the novel itself),60 being seen as a direct assertion of women’s rights by complicit readers. As for the Spanish language versions done during the first large wave of translation of the novel in the 1940s, of which there were at least six issued in dozens of editions between 1941 and 1950, including the most re-printed ones by Antonini (1941), Luaces (1943), and Pereda (1947), the contemporary reader would have to be reminded of the differentiated social and cultural contexts in which the emancipatory potential of the novel was refracted during this first widespread reception in Latin America and Spain respectively.

For in the South American republics, on the one hand, this popularity of Jane Eyre was exactly contemporary with the explicit political and social struggle for women’s civil rights and achievement of suffrage (attained in 1946 in Venezuela, 1947 in Argentina, 1949 in Chile, 1955 in Peru, and 1957 in Colombia, and earlier in some countries: 1924 in Ecuador, 1932 in Uruguay, and 1938 in Bolivia), an event regarded as a fundamental advance in the long and as-yet unfinished movement towards equal rights. Thus, whereas the Seneca Falls Declaration of Sentiments (1848), usually identified as the founding moment of suffragism, is strictly contemporary with the publication of the original English version of Jane Eyre (1847), it was around the time of what is viewed as its final international recognition a hundred years later with the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948) that the novel had its translation boom in Latin America, just as women were attaining equal civil rights in many of the young South American republics following a struggle that had begun in the early twentieth century. In Argentina itself, where this Jane Eyre translation boom began with Antonini’s pioneering 1941 version, Eva Duarte (Evita, 1919–1952) — whose own life story, from humble beginnings and a career as an actress to her work as a trade unionist, political leader and final explicit proclamation as ‘Spiritual Head of the Nation’ (Jefa espiritual de la nación) before she died at the age of thirty-three, offers a no-less sui generis formation narrative in this respect — spoke as follows on national radio about the enactment of the law on women’s suffrage, in which she had been actively involved: ‘My fellow countrywomen, I am even now being presented by the national government with the law that enshrines our civil rights. And I am being presented with it in your company, in the assurance that I do so on behalf and as the representative of all Argentine women, jubilantly feeling how my hands tremble as they touch the laurels that proclaim our victory. Here it is, my sisters, summed up in the cramped print of a few paragraphs — a long history of struggles, setbacks and hopes. And so it contains flares of indignation, the shadows of threatening eclipses, but also the joyous awakening of triumphant dawns, heralding the victory of women over the incomprehension, denials and vested interests of the castes repudiated by our national awakening.’61

Franco’s dictatorship in Spain, on the other hand, did not just abolish the female suffrage sanctioned by the 1931 constitution enacted under the Second Republic and repeal other civil rights won during the previous period, such as the equality of the sexes before the law and the ability to dissolve a marriage. More radically, as part of what was conceived as a struggle of Good against Evil projected on to the two sides that had confronted each other in the Civil War, Francoism applied an explicit National-Catholic programme to restore traditional family values, making canonical marriage the only valid kind and encouraging women to leave the workforce and devote themselves to domestic tasks (so that from 1944 Spain’s labour laws required married women to have their husband’s permission to work). The result was the establishment of a nationalist and religious traditionalism unequalled in the Europe of the day.

It is this contextual difference and relative separation of the cultural destinies of South America and Spain between the 1940s and 1970s, then, that substantially accounts for the different forms of emphasis or self-censorship regarding the potential for female emancipation that are observed in the various translations of Jane Eyre that came out at the time, starting with those of Antonini (1941) and Luaces (1943), two compressed versions that are to some extent equivalent, and that would enjoy great commercial success in their respective regions.

Thus, in South America, it is symptomatic that Antonini’s pioneering Argentine translation was sold, beginning in 1944 and for the three decades to come, in the series of editions published by Acme Agency in Buenos Aires, under the composite title of Jane Eyre: Rebel Soul (Juana Eyre: alma rebelde), with the iconography of its cover design emphasising the idea of the independent and educated woman (you can see the cover, together with the book’s place of publication, on the third screen of the Spanish Covers Map). While this addition to the title, ‘Rebel Soul’, matches that of the Spanish-language version of the 1943 film adaptation of Jane Eyre by Robert Stevenson, with Joan Fontaine and Orson Welles in the roles of Jane and Rochester, it summarizes well the emphasis Antonini would give both to proclamations of gender equality and to the heroine’s erotic intensity.

In the way Jane Eyre translation was approached in Spain in those same years, conversely, starting with Luaces’ version, it is possible to see how the conditioning of the Francoist National-Catholic programme in relation to the social role of women led to varying degrees of self-censorship when it came to the novel’s potential for female emancipation, including its variously explicit eroticism. Insofar as Franco’s dictatorship prescribed the re-establishment of traditional patriarchal culture against the conquests made in the previous Republican period, promoting values and a role for women that did not actually differ greatly from those of the Victorian context in which Jane Eyre originally appeared, it was precisely those moments of the novel that created dissonance in its original context of inscription by deviating from expectations about the social role of women, starting with its claim to equality and its erotic passion, that activated the Spanish translator’s self-censorship in the new context a century later. In fact, Luaces also acted here in a very deliberate and often astute manner, decisively moderating the energy with which Jane asserts her emancipatory positions and experiences her passions, especially the erotic impetus, but also allowing a hidden agenda to show through for those prepared to understand, so that his translation divides readers into accomplices and dupes in more or less subtle and probably automatic ways within this context of censorship in which he was operating.

For this ability to divide readers into accomplices and dupes was something that Luaces exercised from early on, even before he was imprisoned or censored, as can be seen in his work as a writer under the previous dictatorship of Miguel Primo de Rivera (1923–1930), and not least in relation to the civil oppression and erotic repression of women. Take his journalistic text ‘Feminismo y desvergüenza’ (‘Feminism and Shamelessness’), written when he was just 19 and published in the Heraldo Alavés (25 February 1925), not only because it can effectively divide readerships even now, but also because the picture it provides of the female oppression and tension in which his compressed version of Jane Eyre was to appear somewhat later could hardly be bettered. Luaces, the young Republican poet, thunders: