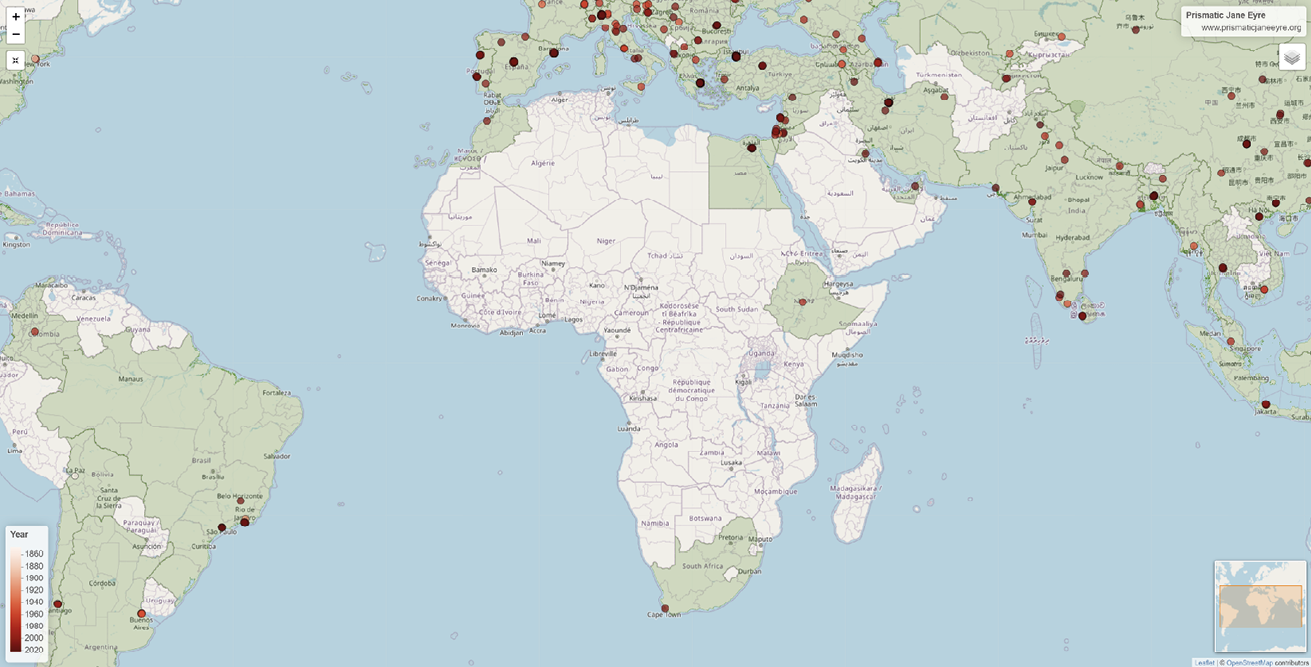

The General Map https://digitalkoine.github.io/je_prismatic_generalmap/ Created by Giovanni Pietro Vitali; © OpenStreetMap contributors

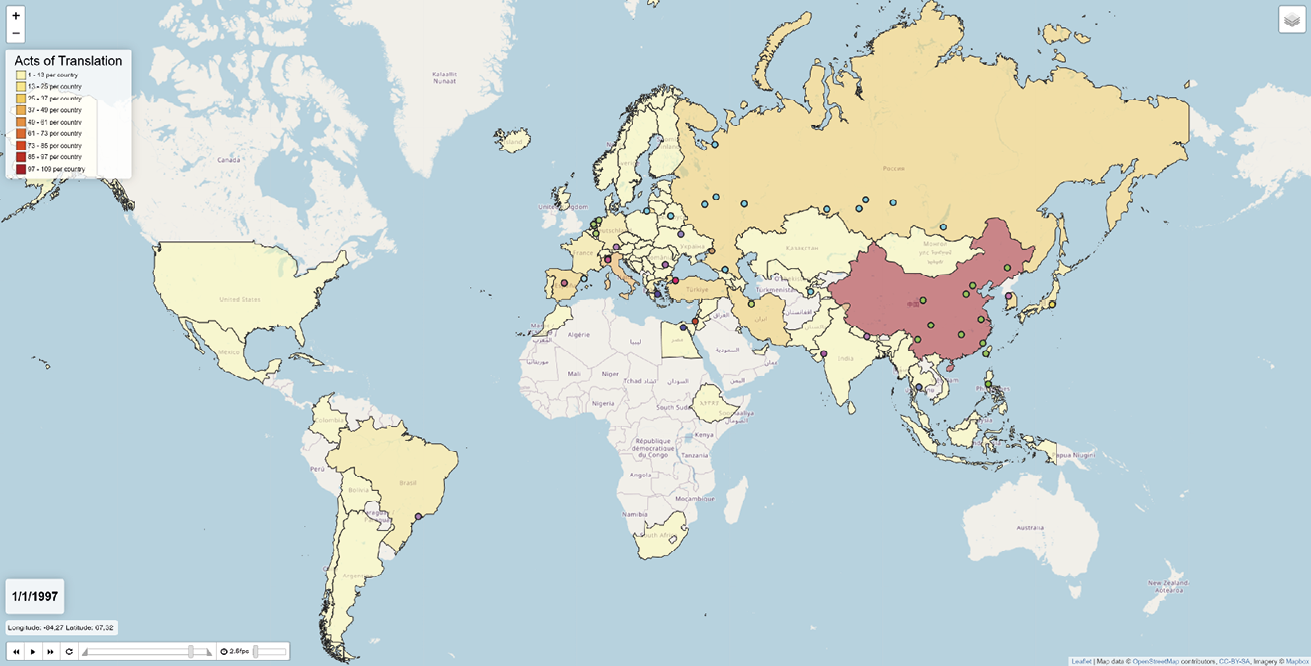

The Time Map https://digitalkoine.github.io/translations_timemap Created by Giovanni Pietro Vitali and Simone Landucci;© OpenStreetMap contributors, © Mapbox

7. Searching for Swahili Jane

© 2023 Annmarie Drury, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0319.11

Although Jane Eyre has travelled widely, its sojourn in the languages of sub-Saharan Africa has been limited. Apart from an Amharic translation (1981), there are only learners’ ‘thesaurus editions’ in Afrikaans and Swahili and a drastically abridged Afrikaans translation.2 My task thus differs somewhat from the work animating other essays here. It is to think about the absence of Jane Eyre from one language of sub-Saharan Africa, Swahili, and then to outline a potentiality. Writing about absence is a peculiar task with methodological complications, and in offering this discussion, I do not mean to argue that there should be a Swahili Jane Eyre. Yet in the context of a ‘Prismatic Jane Eyre’ project, this limitation upon the circulation of the novel — that it has not entered the majority of languages from our second-largest continent — has meaning. If we understand translation as prismatic, then here we find an occlusion, a failure in transmission. Pondering a rich literary sphere that Jane Eyre has not entered illuminates aspects of that sphere, I think, and potential meanings of Brontë’s novel.

The nineteenth-century British novel has special significance in Swahili literary history because it became a vehicle of colonial language regulation. This happened after the Versailles Treaty gave Tanganyika, formerly part of German East Africa, to Britain as a League of Nations mandate — technically not a colony but indistinguishable from one in most practical terms. Early literary translations from English into Swahili, many made in the 1920s, served a policy through which Britain sought to create and promulgate a ‘standard’ form of Swahili. Based on the southern Swahili dialect of Kiunguja — the Swahili of Zanzibar — though not fully Kiunguja itself, the standard Swahili promoted and enforced by the Inter-Territorial Language Committee (ITLC), a colonial agency created for this purpose, was in its inception a language virtually without a literature. Colonial standardization entailed sidelining much of the Swahili literary canon, which lay in poetry composed in northerly dialects and thus violating ‘standard’ rules.3 While translators brought the Bible into Swahili in the nineteenth century — Johann Ludwig Krapf, under the aegis of the Anglican Church Missionary Society, began such work in the 1840s; Edward Steere published his translation of the New Testament in 1879; and William Taylor translated portions including Psalms (1904) — few literary translations from European languages into Swahili existed.4 An abridged translation of Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress (1888) and two early prose renderings from Shakespeare (1900 and 1867) are notable exceptions.5 Wanting texts for classroom instruction, colonial administrators in the 1920s translated fiction, with one man making most of the first generation of translations. This was Frederick Johnson, creator of a dictionary of standard Swahili and the first head of the ITLC, who sometimes translated with the African Edwin (E. W.) Brenn.6 Johnson was known for translating rapidly at his typewriter,7 and outside of translation, his work extended to the joint authorship in Swahili of a small book on citizenship, Uraia, that, as Emma Hunter shows, delineates a conception of freedom ‘as security’ rather than ‘as political liberty’, one consonant with a vision of Tanganyika as part of ‘a wider imperial family’.8 Johnson’s translations, favouring Victorian novels, included selections from Rudyard Kipling’s Jungle Book and Second Jungle Book, published in 1929 as Hadithi za Maugli: Mtoto Aliyelelewa na Mbwa Mwitu [Stories of Mowgli: The Child Raised by Wolves]; an abridged translation with Brenn of Rider Haggard’s King Solomon’s Mines, published as Mashimo ya Mfalme Sulemani (1929); a translation with Brenn of Robert Louis Stevenson’s Treasure Island (1929); an abridged translation of Haggard’s Allan Quatermain, published in 1934 as Hadithi ya Allan Quatermain; and a translation of Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels.9 This corpus suggests that a type of fiction favoured by the language-standardizing translators was the boy’s adventure story with imperialist resonance. Whether Johnson and his colleagues made their choices for reasons of personal affinity, in that they could most rapidly translate and abridge texts they knew from their youth; out of conscious ideological purpose, as Ousseina Alidou persuasively argues was done by another colonial official with a magazine serialization based on Booker T. Washington’s Up from Slavery in Zanzibar in the mid-1930s; or because they imagined these fictions would engage school students, primarily boys, one readily perceives how the pattern of selection would have omitted Jane Eyre.10

Thus the first translations of British novels, often abridged, into Swahili created two registers of problem. First, they turned nineteenth-century British fiction into a literature of linguistic enforcement, through volumes asserting — with the ITLC’s literal seal of approval — that the right kind of Swahili was this variety created in translations by British men of books by other British men. Secondly, the very language of the translations signalled alienness from the Swahili literary tradition, for it neglected the art of prose narration as it then existed in Swahili — an art developed in historical chronicles and local storytelling traditions, for example, and influenced by Arabic genres; one feature was the fluidity with which prose accommodated interpolation of poetry.11 The Kenyan poet Abdilatif Abdalla (b. 1946), who writes in the Swahili dialect of Kimvita, has remarked on how this early set of translations promulgated a narrative language shaped by English, one in which ‘mawako au miundo ya sentensi zile si ya Kiswahili, ya Kiingereza, mpaka maneno pia — maanake kunatumika maneno ya Kiswahili lakini mtungo ule wa sentensi si Kiswahili’: ‘the construction or forms of the sentences are not Swahili but English, and the words as well — that is, Swahili words are being used but the composition of the sentence is not Swahili.’12 His comment suggests how these translations, estranged from Swahili literary language, had the potential to alienate readers in the schools of Zanzibar and beyond.

Of course, these translations into (a kind of) Swahili formed but one facet of the identity of British fiction in colonial East Africa. The rich multilingualism of East Africa, in play whenever one considers literary circulation there, invites us to consider as well the experience of English-language readers in colonial schools. Many students who encountered Stevenson’s Treasure Island or the novels of Haggard in colonial East Africa read the books in English rather than Swahili, and here, too, British literature had strong affiliations with colonial oversight. The Kenyan author Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o, writing of his years at Alliance High School, the first secondary school in Kenya for Africans, describes his experience learning but never quite gaining satisfaction from British novels he found in the school library. English was the language of instruction at Alliance, and Ngũgĩ, whose first language is Gĩkũyũ, writes of reading in English some of the same fictions I have named as translated into Swahili by colonial translators — including Treasure Island and King Solomon’s Mines. This reading generated a recognition about the pervasiveness of imperial culture, Ngũgĩ explains, an understanding that ‘[e]ven in fiction I was not going to escape the theme of empire building.’ It also created a sense of entrapment: ‘I looked in vain for writings that I could identify with fully. The choice, it seemed, was between the imperial narratives that disfigured my body and soul, and the liberal ones that restored my body but still disfigured my soul.’ At the same time, Ngũgĩ admired certain authors. He credits Shakespeare with a regeneration of Swahili drama and recalls how he found in Emily Brontë’s Wuthering Heights a narrative style that chimed with his experience of stories at home: ‘With its many voices, it felt much the way narratives of real life unfolded in my village, an episode by one narrator followed by others that added to it and enriched the same theme.’13 Stevenson made Ngũgĩ want to write while motivating his ‘first major literary dispute’, an argument with a friend over whether an aspiring author needed external endorsement, ‘license to write’.14 In illuminating the complicated experience of reading British literature as a colonial East African subject, Ngũgĩ’s account suggests associations that might attach to Jane Eyre in the multilingual literary sphere a Swahili translation would enter — that might or might have attached to it, that is, since generations of East Africans have no experience of colonial education, though they may well have experience of its legacies. The complexity of East African reading publics, in terms of language background and educational profile, emerges vividly as one tries to imagine a Swahili Jane Eyre. Ngũgĩ’s account brings us, intriguingly, to a sister-novel of Jane Eyre, but we have not yet found a Swahili Jane.

In the post-independence era, translation of the Anglophone African novel into Swahili had particular importance, with novels by Ngũgĩ, Ayi Kwei Armah, and Chinua Achebe, for example, all appearing in Swahili translation; a translation of Ferdinand Oyono’s Une vie de boi (1956), made from John Reed’s English translation Houseboy (1966), appeared in the same series as many of these.15 Yet translators also revisited the nineteenth-century British novel in a series of new translations published in the years just before independence and reissued in Nairobi in the 1990s, including translations of Charles Dickens’s David Copperfield and Oliver Twist, R. M. Ballantyne’s Coral Island, and Jules Verne’s Around the World in Eighty Days, in addition to Mark Twain’s Tom Sawyer. A chapbook translation of Arthur Conan Doyle’s ‘The Adventure of the Speckled Band’ appeared, sponsored by the Sherlock Holmes Society of Kenya, and a translation of Conan Doyle’s Hound of the Baskervilles was later published.16 In this near- and post-independence translating, East African translators (generally with Swahili as a first or second language) play a primary role, more hands are at work, and we see something more of what Donald Frame calls ‘free literary translation’ — that is, work undertaken at the choice of the translator — even as some similarities to the colonial-era bookshelf emerge.17 Yet no fiction by a Brontë figures in this phase of translation.

We have thus identified two absences of Jane from the body of English-language fiction in Swahili translation, an early and a more recent one, and at this point it is useful to flip the model and ask what place in Swahili literature a Swahili Jane might have found, or yet find. What meaning might Jane Eyre have in the Swahili literary context? With what Swahili literature might it be in conversation? The poet and scholar Alamin Mazrui encourages us to adopt this kind of approach when he posits that Swahili culture places special emphasis on relations between translated literature and literature written in Swahili: ‘Contrary to the focus of translation studies in the West on the relationship between the translated text and the original text, the most pressing issue in Swahiliphone Africa has been about the relationship of the translated text to the literature of its translating language,’ he writes.18 In imagining such relationships for a Swahili Jane, gender emerges as a key consideration.

Most literary translations into Swahili have been created by men, and few novels written by women in any language have been translated into Swahili. Setting aside children’s literature, the one novel I know in Swahili translation that was authored by a woman is Mariama Bâ’s Une si longue lettre (1979), translated by Clement Maganga and published in 2017 in Tanzania.19 Bâ’s epistolary novel, part autobiographical, probes the lives of women in Senegal. In this sense, its entrance into Swahili endorses Mazrui’s earlier speculation that for women in Swahiliphone Africa, literary translation has particular value as a vehicle for social change: ‘For women, translated texts may function as potential instruments of counterhegemonic discourses against patriarchy.’ Mazrui notes that when Khadija Bachoo, ‘an East African woman of Swahili-Muslim background’, wrote to him in 2004 about her plan to translate Nawal el Saadawi’s God Dies by the Nile, an interest in social critique inspired the project: ‘[s]he regarded God Dies by the Nile as a way of saying what she as a Swahili woman had wanted to say but was unable to do for reasons of cultural censorship. Because the translated work deals with a “foreign land” and a “foreign culture” out there, she believed it stood a better chance of escaping hostile reception from her patriarchal culture.’20 Yet the translation never appeared. Here we find a link between feminine figures, real and fictional alike, and social critique. Is this a space where Jane Eyre might enter?

Mazrui’s thoughts also resonate with the career in Swahili translation of Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, which has a few unusual features: to start, it has been translated twice, each time by a woman and with each translation possessing ‘counterhegemonic’ or quietly countercultural elements; the second, or more recent, translation might be considered richly counterhegemonic, the first in possession of countercultural elements. The first translation of Alice into Swahili, Elisi katika Nchi ya Ajabu (1940), was created by Ermyntrude Virginia St Lo Conan Davies (E. V. St Lo), who had returned to England after working as an Anglican nun in East Africa. According to Ida Hadjivayanis, Conan Davies felt ‘disillusioned’ with her order, subsequently studied nursing and midwifery in London, and began translating Alice while working as a nurse in Tanganyika, in the mid-1930s.21 In some ways, Elisi aligns with colonial efforts to standardize Swahili; published by Sheldon Press, an arm of the Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge, it received the imprimatur of the Inter-Territorial Language Committee, and its creator was a native speaker of English. Yet Elisi also differs from the first generation of translations made by ITLC officials: it was created outside of the colonial bureaucracy per se; it was by a woman; and it features a girl protagonist. In her wish to transfigure Alice into a Swahili girl, Conan Davies makes memorable use of John Tenniel’s illustrations for Carroll’s text. Elisi appears as an African child, and the mad hatter wears a fez. The Red Queen is still the same queen, however, as Hadjivayanis, the second translator of Alice’s Adventures, points out. In her re-translation of the book in 2015, Alisi Ndani ya Nchi ya Ajabu, Hadjivayanis scrutinizes the Conan Davies translation — an unusual instance of a re-translation in Swahili elaborating critical commentary on translation choices from the colonial era. Hadjivayanis argues that Alice is and should remain English; that the immutability of the Red Queen in Conan Davies’ translation betrays its colonialist agenda; and that the first translation is mistaken in the very naming of its protagonist: the better form of ‘Alice’ in Swahili is ‘Alisi’.22 In and through the work of Hadjivayanis, we discover the figure of Alice cast and re-cast by women translators to serve a calculated sense of who Alice should be to Swahili readers. The career of Alice’s Adventures in translation suggests that feminine figures in Swahili literary translation possess potent mutability. There is also a spectre of Jane in Alice. Carroll’s novel owes something to Jane Eyre, and to Oliver Twist behind that: in the successive displacements of its female protagonist and the corresponding encounters with a gallery of interlocutors, in its satire on education and social rituals, and in the threats and violence with which its protagonist contends. Jane is partially translated into Alice, and Alice is translated into Swahili.

Intertwined with Mazrui’s remarks on women translating, and with the early loneliness of Conan Davies’ Elisi as a book about a girl for girls first of all, are questions about girls’ and women’s literacy in East Africa. While there is not opportunity here to explore this subject in depth, we can note that the historian Corrie Decker documents an influential anxiety about women’s writing, specifically, during the colonial era in Zanzibar — the era of the ITLC’s translations of Haggard and Stevenson. Literacy certainly existed in Zanzibar before colonial schools. But a concept of literacy that entailed writing for girls presented special challenges:

Whereas religious performances and elocution contests were familiar and respectable expressions of a schoolgirl’s new literacy skills, writing was suspect. In the Western schools, literacy was understood as the ability to read, speak, and write. Many Zanzibaris of the time, though, believed that if a girl learned how to write she would write love letters to boys. This was one of the main reasons parents were initially wary of sending girls to the government schools. Similarly in Kenya, as Lynn Thomas explains, there was a close “association between [girls’] schooling and unrestrained sexuality”.23

In colonial Zanzibar, Decker documents, schoolgirls on their way to ‘modern literacies’ negotiated societal fears about their practice of written self-expression.

Brontë, of course, knew about problems faced by women writers, in idea and in fact. Arriving back with her, I would like to ask a question centred in Jane Eyre and in the Swahili literary sphere. Is it possible to discern a textual space for a Swahili Jane Eyre: to imagine it situated among existing Swahili literature, to see Jane Eyre and Swahili literary creations gesturing towards one another? If so, how might that look?

To explore the question, we can think about passages from Jane Eyre and the Swahili canon side by side. When I undertake this experiment, scenes from a contemporary novel and from a classic, mid-nineteenth-century poem surface on the Swahili side and, from Jane Eyre, a meditation early in Chapter Twelve on the frustration of women who long for work of more interest than their society allows. Here Jane, having remarked on her own discontent, considers the situation of women generally:

It is vain to say human beings ought to be satisfied with tranquility: they must have action; and they will make it if they cannot find it. Millions are condemned to a stiller doom than mine, and millions are in silent revolt against their lot. Nobody knows how many rebellions besides political rebellions ferment in the masses of life which people earth. Women are supposed to be very calm generally: but women feel just as men feel; they need exercise for their faculties, and a field for their efforts, as much as their brothers do; they suffer from too rigid a restraint, too absolute a stagnation, precisely as men would suffer; and it is narrow-minded in their more privileged fellow-creatures to say that they ought to confine themselves to making puddings and knitting stockings, to playing on the piano and embroidering bags. It is thoughtless to condemn them, or laugh at them, if they seek to do more or learn more than custom has pronounced necessary for their sex.24

Associatively, I connect Jane’s musings with a scene from Rosa Mistika (1971), the first novel by the Tanzanian author Euphrase Kezilahabi: a fiction in his early, social-realist vein that focuses on inequity and abuse faced by girls in East Africa’s educational system, as well as in family life. In this passage, from Chapter Three, Kezilahabi depicts the domestic space where the titular character Rosa and her sisters congregate — the women’s compound, mji wa wanawake — as a site of profound vulnerability. At this point in the narrative, Rosa is on the threshold of opportunity; she has gained admittance to a girls’ secondary school and eagerly awaits her departure. She and her sister Flora are returning from a trip to town to buy Rosa school supplies. At home, they gather companionably with their younger sisters Stella and Honorata and their neighbour Bigeyo, who gives Rosa a haircut while the girls’ mother, Regina, washes clothes. Then a hawk comes, revealing the powerlessness of the girls and women:

Walipofika nyumbani [Rosa na Flora] walimkuta Bigeyo akiwangojea, kwani Rosa alikuwa amemwambia aje amnyoe.

Walikuwa wamekaa kivulini chini ya mchungwa. Regina alikuwa akifua nguo za Rosa. Mkasi ulilia, ‘Kacha kacha, kachu’ juu ya kichwa cha Rosa. Rosa alikuwa akijitazama ndani ya kioo kila wakati, alimwongoza Bigeyo asijekata sana nywele zake za mbele karibu na uso. Stella aliona kitu fulani kinashuka kasi sana. Alipiga kelele hali akitupa mikono juu.

‘Swa! Swa! Swa!’

Wengine pia waliamka na kupiga kelele. Kazi bure. Kifaranga kimoja kilikwenda kinaning’inia kati ya kucha za mwewe. Walibakia kuhesabu vilivyosalia.

‘Vilikuwa kumi. Sasa vimebaki vitatu!’ Flora alishangaa. Rosa alikaa chini tena kunyolewa. Muda si mrefu mwewe alirudi. Safari hii Honorata ndiye alikuwa wa kwanza kumwona.

‘Swa! Swa! Swa!’ alitupa mikono juu, ‘Swa!’ Mwewe alikuwa amekwisha chukua kifaranga kingine. Zamu hii hakuenda mbali. Alitua juu ya mti karibu na mji. Wasichana walianza kumtupia mawe lakini hayakumfikia. Mwewe alikula kifaranga bila kujali. Alipomaliza aliruka kwa raha ya shibe. Vifaranga vilibaki viwili. Ilionekana kama kwamba hata mwewe alifahamu kwamba huu ulikuwa mji wa wanawake.

When they [Rosa and Flora] reached home, they found Bigeyo waiting for them, as Rosa had asked her to come cut her hair.

They were sitting in the shade of an orange tree. Regina was washing Rosa’s clothes. The scissors snipped, ‘Kacha kacha, kachu’, over Rosa’s head. Rosa was looking at herself in the mirror constantly, directing Bigeyo not to cut too much around her face. Stella saw something descending at great speed. She shouted, throwing up her arms.

‘Swa! Swa! Swa!’

The others, too, started and shouted. But it was useless. One chick went, dangling from the claws of the hawk. The girls were left to count the remaining ones.

‘There were ten. Now there are three!’ Flora exclaimed. Rosa sat back down for her haircut. Soon the hawk returned. This time Honorata was the first to spot it.

‘Swa! Swa! Swa!’ she threw up her arms, ‘Swa!’ The hawk had already snatched another chick. This time it didn’t go far. It alighted on a tree near the compound. The girls threw stones at it, but their throws fell short. The hawk ate the chick unconcernedly. When it finished, it leaped about with the delight of a full stomach. Two chicks remained. It seemed even the hawk understood that this was a women’s compound.25

Rosa and the other schoolgirls in Kezilahabi’s pioneering novel, which was banned in schools before becoming a set text there, seek to ‘learn more’ — to borrow the words of Jane — but in doing so in a patriarchal society unprepared to support their aspirations, they meet with failure and tragedy. This early scene in the women’s compound foreshadows that loss. As Rosa looks towards secondary school with hopeful apprehension, Kezilahabi signals that her existence is fretted with vulnerabilities. A few pages earlier, as Rosa and Flora journey to town, young men try to stop them on the road, and Kezilahabi describes the girls’ flight in imagery that connects to the coming scene in the compound: refusing to look back at the young men whistling at them, the sisters ‘kept running, like birds who had barely escaped to safety’ (‘waliendelea kukimbia kama ndege walionusurika’).26 As much as these girls may desire and deserve educational opportunity, Kezilahabi’s imagery suggests, they face incessant risk in pursuing it.

In Rosa Mistika, Kezilahabi shares with Brontë a thought: a critical interest in educational structures and modes — in what they should be and in how they fail. His unsparing accounts of the violence Rosa experiences, including sexual violence, and of her sexual and reproductive life no doubt caused the novel’s initial banning. Rosa, like Jane (and like Alice in a lighter-hearted rendition), suffers displacements, threats, and violence. Imagery of birds, central to Kezilahabi’s representation of Rosa’s vulnerability in Chapter Three, circulates in Jane Eyre, where Jane reads Thomas Bewick’s History of English Birds in the novel’s opening pages and where Rochester, attempting later to characterize Jane to herself, delivers an assessment in such imagery: ‘I see at intervals the glance of a curious sort of bird through the close-set bars of a cage.’27 While there is not space to elaborate this comparison fully, it is evident that Brontë and Kezilahabi both use imagery of birds to explore questions of power. Bird imagery captures an intertwining of vulnerability and potential liberation that resonates with the circumstances of protagonists who seek only ‘a field for their efforts’ — or, as Kezilahabi has it in another simile, ‘air, water and light’ (‘maji, hewa na mwanga’).28 Improbably, Kezilahabi entered Rosa Mistika for an English-language literary prize, as Roberto Gaudioso reports, ‘kwa kuchokoza’: to provoke.29 Possibly the critical stance shared with a writer such as Brontë, in addition to colonial inheritances in the post-colonial educational system, contributed to his choice to do so.

The Utendi wa Mwana Kupona, or Mwana Kupona’s Poem, composed in 1858 by Mwana Kupona binti Msham, centres also in a women’s space. It represents a domestic transmission of knowledge from mother to daughter in which the act of writing figures centrally. This is a second scene we might connect with Jane’s meditation in Chapter 12. Mwana Kupona, a renowned poet of nineteenth-century Pate, explains to her daughter how to negotiate her world. The provision of ink and paper (‘wino na qaratasi’) and the daughter’s role as her mother’s scribe figure in the poem’s opening stanzas, here in the translation of J. W. T. Allen:

|

(1) |

|

|

Negema wangu bintu |

Come here, my daughter, and listen to my advice; young though you are, perhaps you will pay attention to it. |

|

(2) |

|

|

Maradhi yamenishika |

I have been ill for a whole year and have not had an opportunity to talk properly to you. |

|

(3) |

|

|

Ndoo mbee ujilisi |

Come forward and sit down with paper and ink. I have something that I want to say to you. |

Among the mother’s advice is her admonition that her daughter must win approval from five entities, including God and her husband. The poem then dilates on how the daughter should comport herself to ensure her husband’s happiness:

|

(22) |

|

|

Mama pulika maneno |

Listen to me, my dear; a woman requires the approval of five before she has peace in this world and the next. |

|

(23) |

|

|

Nda Mngu na Mtumewe |

Of God and His Prophet; of father and mother, as you know; and the fifth of her husband as has been said again and again. |

|

(24) |

|

|

Naawe radhi mumeo |

Please your husband all the days that you live with him and on the day that you receive your call, his approval will be clear. |

|

(25) |

|

|

Na ufapo wewe mbee |

If you die first, seek his blessing and go with it upon you, so you will find the way. |

|

(26) |

|

|

Siku ufufuliwao |

When you rise again the choice is your husband’s; he will be asked his will and that will be done. |

|

(27) |

|

|

Kipenda wende peponi |

If he wishes you to go to Paradise, at once you will go; if he says to Hell, there must you be sent. |

|

(28) |

|

|

Keti naye kwa adabu |

Live with him orderly, anger him not; if he rebuke you, do not argue; try to be silent. |

|

(29) |

|

|

Enda naye kwa imani |

Give him all your heart, do not refuse what he wants; listen to each other, for obstinacy is hurtful. |

|

(30) |

|

|

Kitoka agana naye |

If he goes out, see him off; on his return welcome him and then make ready a place for him to rest.30 |

Affiliations between these stanzas and Jane’s musings are complex. One might argue that Utendi wa Mwana Kupona (titled in one early English translation as a poem ‘upon the wifely duty’), in the detailed instruction it sets forth, reveals a world where women live under ‘too rigid a restraint’. Or one might agree with an interpretation of the poem — advanced in a reading by Ann Biersteker, in particular — as subverting the social norms it ostensibly embraces.31 We might also, however else we understand it, highlight the significance of women’s writing to the imaginary of this poem, which sets before us a scene of feminine knowledge and agency — the bringing of pen and ink by a daughter, under a mother’s instruction; the preparation for writing; the prizing of knowledge-transmission signalled in the phrase ‘pulika maneno’, ‘listen to these words’, in the first stanza of line 22 (which Allen’s generally sound translation elides to ‘listen to me’), a phrase that signals as well the deep intertwining of orality and literacy in Swahili letters — which sets before us all these things, that is, prior to elaborating any explicit instruction for navigating life as a woman on the nineteenth-century Swahili coast. The role of caregiver that Mwana Kupona advises her daughter to assume in relation to her husband bears a resemblance to the role Jane holds in marriage to the blind Rochester in Chapter 38, which intertwines Jane’s happiness during a decade of marriage with her identity as a writer recording her experience: ‘My tale draws to its close […] I have now been married ten years. I know what it is to live entirely for and with what I love best on earth.’ Utendi wa Mwana Kupona likewise links writing, and language itself, to ‘wifely duty’. As Farouk Topan notes, the poem treats language as the provenance of the wife, while ‘[t]he husband, on the contrary, is presented as someone who is almost devoid of speech, or someone to be taken as such.’32 Defining themselves through the act of writing, both Mwana Kupona and Brontë create layers of such self-definition by making the feminine figures at the center of their creations into keepers of language.

But here, having no Swahili Jane Eyre, we reach a limit of this line of thought. What words would a Swahiliphone translator choose for the passage on ‘a stiller doom’ and ‘silent revolt’? What would the register of language be? Where might we find lexical resonance with Euphrase Kezilahabi or Mwana Kupona, and what might that suggest to us about the meanings of those writers and their texts in the Swahili sphere? What would Jane’s name be, in Swahili? She is unnamed for now, but perhaps not entirely unimagined.

Works Cited

Abdalla, Abdilatif, Personal communication, 2 June 2019.

Achebe, Chinua, Shujaa Okonkwo, trans. by Clement Ndulute (Nairobi: East African Publishing House, 1973).

Alidou, Ousseina, ‘Booker T. Washington in Africa: Between Education and (Re)Colonization’, in A Thousand Flowers: Social Struggles Against Structural Adjustment in African Universities, ed. by Silvia Federici, George Caffentzis, and Ousseina Alidou (Trenton, NJ: Africa World Press, 2000), pp. 25–36.

Arenberg, Meg, ‘Converting Achebe’s Africa for the New Tanzanian: Things Fall Apart in Swahili Translation’, Eastern African Literary and Cultural Studies, 2 (2016), 124–35, https://doi.org/10.1080/23277408.2016.1274357

Armah, Ayi Kwei, Wema Hawajazaliwa, trans. by Abdilatif Abdalla (Nairobi: Heinemann Educational, 1976).

Bâ, Mariama, Barua Ndefu Kama Hii, trans. by Clement Maganga (Dar es Salaam: Mkuki na Nyota, 2017).

Ballantyne, R. M., Kisiwa cha Matumbawe, adapted by E. F. Dodd, trans. by Elizabeth Pamba (Nairobi: Macmillan Kenya, 1993).

Biersteker, Ann, ‘Language, Poetry, and Power: A Reconsideration of “Utendi Wa Mwana Kupona”’, in Faces of Islam in African Literature, ed. by Kenneth W. Harrow (London: James Currey, 1991), pp. 59–77.

Binti Msham, Mwana Kupona, ‘Utendi wa Mwana Kupona’, in Tendi: Six Examples of a Classical Verse Form, ed. and trans. by J. W. T. Allen (London: Heinemann, 1971).

Carroll, Lewis, Alisi Ndani ya Nchi ya Ajabu, trans. by Ida Hadjivayanis (Port Laois, Ireland: Evertype, 2015).

Conan Doyle, Arthur, Maajabu ya Utepe Wenye Madoadoa, trans. by George M. Gatero and Leonard L. Muaka (Nairobi: Battered Silicon Dispatch Box, 1993).

——, Mbwa wa Familia ya Baskerville, trans. by Hassan O. Ali (Shelburne, Ontario: Battered Silicon Dispatch Box, 1999).

Conlon-McKenna, Marita. Chini ya Mti wa Matumaini (Dar es Salaam: Mkuki na Nyota, 2010).

Decker, Corrie, ‘Reading, Writing, and Respectability: How Schoolgirls Developed Modern Literacies in Colonial Zanzibar’, The International Journal of African Historical Studies, 43 (2010), 89–114.

Dickens, Charles, Visa vya David Copperfield, trans. by Alfred Kingwe (Nairobi: Macmillan Kenya, 1993).

——, Visa vya Oliver Twist, trans. by Amina C. Vuso (Nairobi: Macmillan Kenya, 1993).

Drury, Annmarie, Translation as Transformation in Victorian Poetry (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2015), https://doi.org/10.1093/res/hgw027

Frame, Donald, ‘Pleasures and Problems of Translation’, in The Craft of Translation, ed. by John Biguenet and Rainer Schulte (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1989), pp. 70–92.

Frankl, P. J. L., ‘Johann Ludwig Krapf and the Birth of Swahili Studies’, Zeitschrift de Deutschen Morgenländischen Gesellschaft, 142 (1992), 12–20.

——, ‘W. R. Taylor (1856–1927): England’s Greatest Swahili Scholar’, Afrikanistische Arbeitspapiere, 60 (1999), 161–74.

Gaudioso, Roberto, ‘To the Eternal Presence of Poetry, to Euphrase Kezilahabi’, Swahili Forum, 27 (2020), 5–16.

Geider, Thomas, ‘A Survey of World Literature Translated into Swahili’, in Beyond the Language Issue: The Production, Mediation and Reception of Creative Writing in African Languages, ed. by Anja Oed and Uta Reuster-Jahn (Köln: Rüdiger Köppe, 2008), pp. 67–84.

Hadjivayanis, Ida, ‘The Swahili Elisi: In Unguja Dialect’, in Alice in a World of Wonderlands: The Translations of Lewis Carroll’s Masterpiece, Vol. 1, ed. by Jon A. Lindseth and Alan Tannenbaum (New Castle, Delaware: Oak Knoll Press, 2015), pp. 567–72.

Haggard, H. Rider, Mashimo ya Mfalme Sulemani, trans. by Frederick Johnson and E. W. Brenn (London: Longman, 1929).

——, Hadithi ya Allan Quartermain, trans. by Frederick Johnson (London: Sheldon Press, 1934).

Heanley, Robert Marshall, A Memoir of Edward Steere: Third Missionary Bishop in Central Africa (London: George Bell and Sons, 1888).

Hunter, Emma, ‘Dutiful Subjects, Patriotic Citizens, and the Concept of Good Citizenship in Twentieth-Century Tanzania’, The Historical Journal, 56, no. 1 (2013), 257–77, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0018246X12000623

Iliffe, John, A Modern History of Tanganyika (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1979).

Johnson, G. B., Maisha ya Booker T. Washington: Mtu Mweusi Maarufu (London: Sheldon Press, 1937).

Kezilahabi, Euphrase, Rosa Mistika (Nairobi: Kenya Literature Bureau, 1980 [1971]).

Kipling, Rudyard, Hadithi za Maugli: Mtoto Aliyelelewa na Mbwa Mwitu, trans. by Frederick Johnson (Bombay, Calcutta, Madras, and London: Macmillan, 1929).

Mazrui, Alamin, Swahili Beyond the Boundaries: Literature, Language, and Identity (Athens, OH: Ohio University Press, 2007).

——, Cultural Politics of Translation: East Africa In a Global Context (New York: Routledge, 2016), https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315625836

Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o, Njia Panda, trans. by John Ndeti Somba (Nairobi: East African Publishing House, 1974).

——, Usilie Mpenzi Wangu, trans. by John Ndeti Somba (Nairobi: Heinemann Educational, 1975).

——, Dreams in a Time of War (New York: Anchor, 2010).

——, In the House of the Interpreter (New York: Anchor, 2012).

Oyono, Ferdinand, Boi, trans. by Mabwana Raphael Kahaso and Nathan Mbwele (Nairobi: Heinemann Educational, 1976).

Spaandonck, Marcel van, Practical and Systematical Swahili Bibliography: Linguistics 1850–1963 (Leiden: Brill, 1965).

Stevenson, Robert Louis, Kisiwa chenye Hazina, trans. by Frederick Johnson and E. W. Brenn (London: Longmans, 1929).

Swift, Jonathan, Safari za Gulliver, trans. by Frederick Johnson (London: Sheldon Press, 1932).

Talento, Serena, ‘The “Arabic Story” and the Kingwana Hugo: A (Too Short) History of Literary Translation into Swahili’, in Lugha na Fasihi: Essays in Honor and Memory of Elena Bertoncini Zúbková, ed. by Flavia Aiello and Roberto Gaudioso (Naples: Università degli Studi di Napoli ‘L’Orientale’, 2019), pp. 59–80.

——, Framing Texts — Framing Social Spaces: Conceptualising Literary Translation in three Centuries of Swahili Literature (Köln: Rüdiger Köppe, 2021).

Topan, Farouk, ‘Biography Writing in Swahili’, History in Africa, 24 (1997), 299–307.

——, ‘From Mwana Kupona to Mwavita: Representations of Female Status in Swahili Literature’, in Swahili Modernities: Culture, Politics, and Identity on the East Coast of Africa, ed. by Pat Caplan and Farouk Topan (Trenton, NJ: Africa World Press, 2004), pp. 213–28.

Twain, Mark, Visa vya Tom Sawyer, trans. Benedict Syambo (Nairobi: Macmillan Kenya, 1993).

Verne, Jules, Kuizunguka Dunia kwa Siku Themanini, trans. by Yusuf Kingala (Nairobi: Macmillan Kenya, 1993).

Waliaula, Ken Walibora, ‘The Afterlife of Oyono’s Houseboy in the Swahili Schools Market: To Be or Not to Be Faithful to the Original’, PMLA, 128 (2013), 178–84, https://doi.org/10.1632/pmla.2013.128.1.178

1 I am grateful to Ann Biersteker, Alamin Mazrui, and Clarissa Vierke for discussing ideas with me as I worked on this essay.

2 The Amharic translation is Žénʻéyer (Addis Ababa: Bolé Mātamiya Bét, 1981). I have found neither the translator’s name nor a copy of the book. The ‘thesaurus editions’ in Afrikaans and Swahili (published by ICON Group International, 2008) propose to assist learners both of English and of the relevant African language, but the Swahili edition appears to have been created by a machine and fails where interpretive nuance is required. The abridged Afrikaans version is translated and ed. by Antoinette Stimie (Kaapstad: Oxford University Press, 2005).

3 I explore this problem in Chapter Five of Translation as Transformation in Victorian Poetry (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2015).

4 P. J. L. Frankl, ‘Johann Ludwig Krapf and the Birth of Swahili Studies’, Zeitschrift der Deutschen Morgenländischen Gesellschaft, 142 (1992), 12–20 (p. 13); Robert Marshall Heanley, A Memoir of Edward Steere: Third Missionary Bishop in Central Africa (London: George Bell and Sons, 1888, p. 239); and P. J. L. Frankl, ‘W. R. Taylor (1856–1927): England’s Greatest Swahili Scholar’, AAP, 60 (1999), 161–74 (p. 168). The earliest date for Steere’s translation is 1883 in catalogue records, but Heanley and contemporaneous sources such as the Dictionary of National Biography give 1879 as the date of publication in East Africa. These nineteenth-century scriptural translations present different varieties of Swahili. Krapf’s work precedes settled orthography for Swahili in the Roman alphabet. Steere’s concentration on the dialect of Zanzibar, Kiunguja, pre-dates the British program of standardization based on that dialect; Alamin Mazrui, in Cultural Politics of Translation: East Africa in a Global Context (New York: Routledge, 2016, p. 23) deems it ‘a pan-Swahili dialect’. Taylor translated into Kimvita, the dialect of Mombasa, and as Frankl explains, the fact that Kimvita was spoken by relatively few Christians contributed to the obscurity of his Swahili psalter.

5 The 1888 version of Bunyan was Msafiri, published by the Religious Tract Society for the Universities’ Mission. My sources on prose versions of Shakespeare are Mazrui, Cultural Politics of Translation, pp. 3–4; and Thomas Geider, ‘A Survey of World Literature Translated into Swahili’, in Beyond the Language Issue: The Production, Mediation and Reception of Creative Writing in African Languages, ed. by Anja Oed and Uta Reuster-Jahn (Köln: Rüdiger Köppe, 2008), pp. 67–84 (p. 69). For more on translations from European languages before the 1920s, see Serena Talento, ‘The “Arabic Story” and the Kingwana Hugo: A (Too Short) History of Literary Translation into Swahili’, in Lugha na Fasihi: Essays in Honor and Memory of Elena Bertoncini Zúbková, ed. by Flavia Aiello and Roberto Gaudioso (Naples: Università degli Studi di Napoli ‘L’Orientale’, 2019), pp. 59–80 (pp. 63–4); and Framing Texts — Framing Social Spaces: Conceptualising Literary Translation in three Centuries of Swahili Literature (Köln: Rüdiger Köppe, 2021), Chapter Five and appendices.

6 Johnson does not clarify the extent of Brenn’s work, and it is possible that Brenn contributed to translations beyond those where his ‘help’ (‘msaada’) is acknowledged. John Iliffe identifies Brenn as a ‘senior clerk in the Education Department’ who studied at the Church Missionary Society school in Mombasa, in A Modern History of Tanganyika (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1979), p. 266. Mazrui comments on Brenn’s translation of The Arabian Nights in Cultural Politics of Translation (p. 41).

7 Geider, ‘A Survey of World Literature Translated into Swahili’, p. 73.

8 Emma Hunter, ‘Dutiful Subjects, Patriotic Citizens, and the Concept of Good Citizenship in Twentieth-Century Tanzania’, The Historical Journal, 56, no. 1 (2013), 257–77 (p. 265). Johnson’s fellow author was Stanley Rivers-Smith, the first Director of Education in Tanganyika.

9 The Swahili editions are: Hadithi za Maugli: Mtoto Aliyelelewa na Mbwa Mwitu (London: Macmillan, 1929); Mashimo ya Mfalme Sulemani (London: Longman, 1929; reissued as recently as 1986 by Longmans Kenya in Nairobi); Kisiwa chenye Hazina (London: Longmans, 1929); Hadithi ya Allan Quatermain (London: Sheldon Press, 1934); Safari za Gulliver (London: Sheldon Press, 1932); Mashujaa: Hadithi Za Kiyunani (London: Sheldon Press, 1933). My sources for these titles and dates are Marcel van Spaandonck’s Practical and Systematical Swahili Bibliography: Linguistics 1850–1963 (Leiden: Brill, 1965), which misspells Brenn’s name, and searches in WorldCat and the catalogues of SOAS, University of London and Yale University libraries. Although it is beyond the scope of this essay, Johnson’s selections from American literature would reward consideration. As Talento writes, he translated as well Tales of Uncle Remus and, with Brenn as collaborator, Longfellow’s Song of Hiawatha; see Talento, ‘The “Arabic Story” and the Kingwana Hugo’, pp. 65–6.

10 Ousseina Alidou, ‘Booker T. Washington in Africa: Between Education and (Re)Colonization’, in A Thousand Flowers: Social Struggles Against Structural Adjustment in African Universities, ed. by Silvia Federici, George Caffentzis, and Ousseina Alidou (Trenton, NJ: Africa World Press, 2000), pp. 25–36. Alidou examines G. B. Johnson’s Swahili series in Mazungumzo ya Walimu wa Unguja in 1935, where the figure of Washington is used to endorse provision of vocational rather than scholarly education for Africans. G. B. Johnson, the Chief Inspector of Schools on Zanzibar, soon published a short biography of Washington in Swahili that included excerpts from Up from Slavery in G. B. Johnson’s Swahili translation: Maisha ya Booker T. Washington: Mtu Mweusi Maarufu (London: Sheldon Press, 1937). G. B. Johnson is not to be confused with Frederick Johnson, first head of the ITLC and the ‘Johnson’ referred to elsewhere in this essay.

11 Farouk Topan, ‘Biography Writing in Swahili’, History in Africa, 24 (1997), 299–307 (p. 299).

12 Transcribed (with my translation) from a recording shared by Abdilatif Abdalla of a session at the Swahili Colloquium, University of Bayreuth, Germany, 1 June 2019. Abdalla’s interlocutor, the poet Mohammed Khelef Ghassani, produces an example of such an English-inflected Swahili formulation: mwisho wa siku (at the end of the day), where Swahili narrative would use the formulation hatimaye (finally, at last, in the end).

13 Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o, In the House of the Interpreter (New York: Anchor, 2012), pp. 163–4.

14 Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o, Dreams in a Time of War (New York: Anchor, 2010), p. 220.

15 Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o, Njia Panda [translation of The River Between], trans. by John Ndeti Somba (Nairobi: East African Publishing House, 1974); and Usilie Mpenzi Wangu [translation of Weep Not, Child], trans. by John Ndeti Somba (Nairobi: Heinemann Educational, 1975); Ayi Kwei Armah, Wema Hawajazaliwa, trans. by Abdilatif Abdalla (Nairobi: Heinemann Educational, 1976); and Chinua Achebe, Shujaa Okonkwo [translation of Things Fall Apart], trans. by Clement Ndulute (Nairobi: East African Publishing House, 1973); Ferdinand Oyono, Boi [translation of Une vie de boi via John Reed’s translation Houseboy], trans. by Mabwana Raphael Kahaso and Nathan Mbwele (Nairobi: Heinemann Educational, 1976). On Shujaa Okonkwo see Meg Arenberg, ‘Converting Achebe’s Africa for the New Tanzanian: Things Fall Apart in Swahili Translation’, Eastern African Literary and Cultural Studies, 2 (2016), 124–35; on Boi see Ken Walibora Waliaula, ‘The Afterlife of Oyono’s Houseboy in the Swahili Schools Market: To Be or Not to Be Faithful to the Original’, PMLA, 128 (2013), 178–84. Sources for bibliographic details are author’s copies and searches in WorldCat and the catalogues of SOAS, University of London and Yale University libraries.

16 On the original, pre-independence publication of novels here listed in their 1993 printing, my source is Mazrui (Cultural Politics of Translation, p. 5). They are Visa vya David Copperfield, trans. by Alfred Kingwe (Nairobi: Macmillan Kenya, 1993); Visa vya Oliver Twist, trans. by Amina C. Vuso (Nairobi: Macmillan Kenya, 1993); Kisiwa cha Matumbawe, adapted by E. F. Dodd, trans. by Elizabeth Pamba (Nairobi: Macmillan Kenya, 1993); Kuizunguka Dunia kwa Siku Themanini, trans. by Yusuf Kingala (Nairobi: Macmillan Kenya, 1993); Visa vya Tom Sawyer, trans. by Benedict Syambo (Nairobi: Macmillan Kenya, 1993). The translations of Conan Doyle are Maajabu ya Utepe Wenye Madoadoa, trans. by George M. Gatero and Leonard L. Muaka (Nairobi: Battered Silicon Dispatch Box, 1993); and Mbwa wa Familia ya Baskerville, trans. by Hassan O. Ali (Shelburne, Ontario: Battered Silicon Dispatch Box, 1999). Sources are searches in WorldCat and the catalogues of SOAS, University of London and Yale University libraries.

17 Donald Frame, ‘Pleasures and Problems of Translation’, in The Craft of Translation, ed. by John Biguenet and Rainer Schulte (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1989), pp. 70–92 (p. 70).

18 Alamin Mazrui, Swahili Beyond the Boundaries: Literature, Language, and Identity (Athens, OH: Ohio University Press, 2007), p. 123.

19 Mariama Bâ, Barua Ndefu Kama Hii, trans. by Clement Maganga (Dar es Salaam: Mkuki na Nyota, 2017); Mazrui discusses Maganga and the publishing context for his translation in Cultural Politics of Translation (pp. 75–76, 152). The children’s novel Under the Hawthorne Tree by the Irish writer Marita Conlon-McKenna has also been translated into Swahili: Marita Conlon-McKenna, Chini ya Mti wa Matumaini (Dar es Salaam: Mkuki na Nyota, 2010); bibliographic records identify no translator.

20 Mazrui, Swahili Beyond the Boundaries, p. 144.

21 Ida Hadjivayanis, ‘The Swahili Elisi: In Unguja Dialect’, in Alice in a World of Wonderlands: The Translations of Lewis Carroll’s Masterpiece, Vol. 1, ed. by Jon A. Lindseth and Alan Tannenbaum (New Castle, Delaware: Oak Knoll Press, 2015), 567–72 (p. 568).

22 Lewis Carroll, Alisi Ndani ya Nchi ya Ajabu, trans. by Ida Hadjivayanis (Port Laois, Ireland: Evertype, 2015), p. viii.

23 Corrie Decker, ‘Reading, Writing, and Respectability: How Schoolgirls Developed Modern Literacies in Colonial Zanzibar’, The International Journal of African Historical Studies, 43 (2010), 89–114 (pp. 101–2).

24 JE, Ch. 12.

25 Euphrase Kezilahabi, Rosa Mistika (Nairobi: Kenya Literature Bureau, 1980 [1971]), p. 22 [my translation].

26 Kezilahabi, Rosa Mistika, p. 20 [my translation]. Kezilahabi’s use of the verb kunusurika (‘to be saved’, ‘to just manage to escape’) in this image contributes to a sense of ceaseless vulnerability. In the simile, the flight of birds comes not so that they will be saved but because they have (just barely) escaped some danger.

27 JE, Ch. 14.

28 Kezilahabi, Rosa Mistika, p. 56 [my translation].

29 Roberto Guadioso, ‘To the Eternal Presence of Poetry, to Euphrase Kezilahabi’, Swahili Forum, 27 (2020), 5–16 (p. 6).

30 Mwana Kupona binti Msham, ‘Utendi wa Mwana Kupona’, in Tendi: Six Examples of a Classical Verse Form with Translations and Notes, ed. and trans. by J. W. T. Allen (London: Heinemann, 1971).

31 Ann Biersteker, ‘Language, Poetry, and Power: A Reconsideration of “Utendi Wa Mwana Kupona”’, in Faces of Islam in African Literature, ed. by Kenneth W. Harrow (London: James Currey, 1991), pp. 59–77.

32 Farouk Topan, ‘From Mwana Kupona to Mwavita: Representations of Female Status in Swahili Literature’, in Swahili Modernities: Culture, Politics, and Identity on the East Coast of Africa, ed. by Pat Caplan and Farouk Topan (Trenton, NJ: Africa World Press, 2004), pp. 213–28 (p. 219).