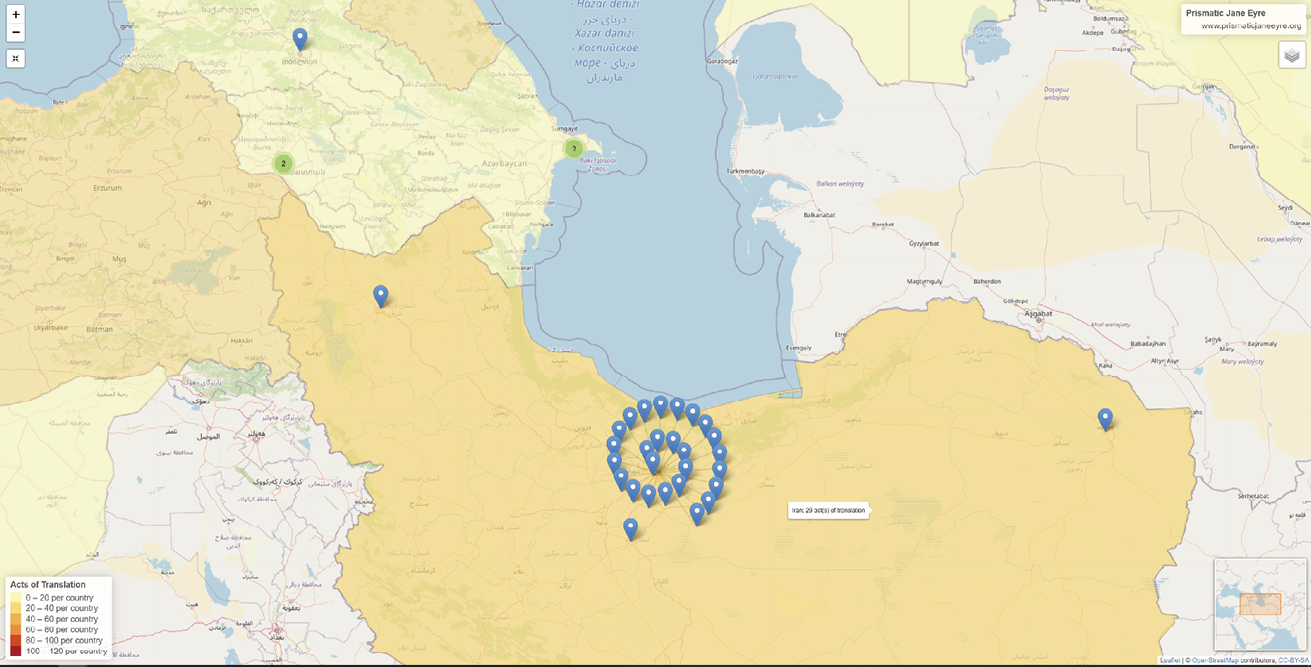

The World Map https://digitalkoine.github.io/je_prismatic_map Created by Giovanni Pietro Vitali; maps © Thunderforest, data © OpenStreetMap contributors

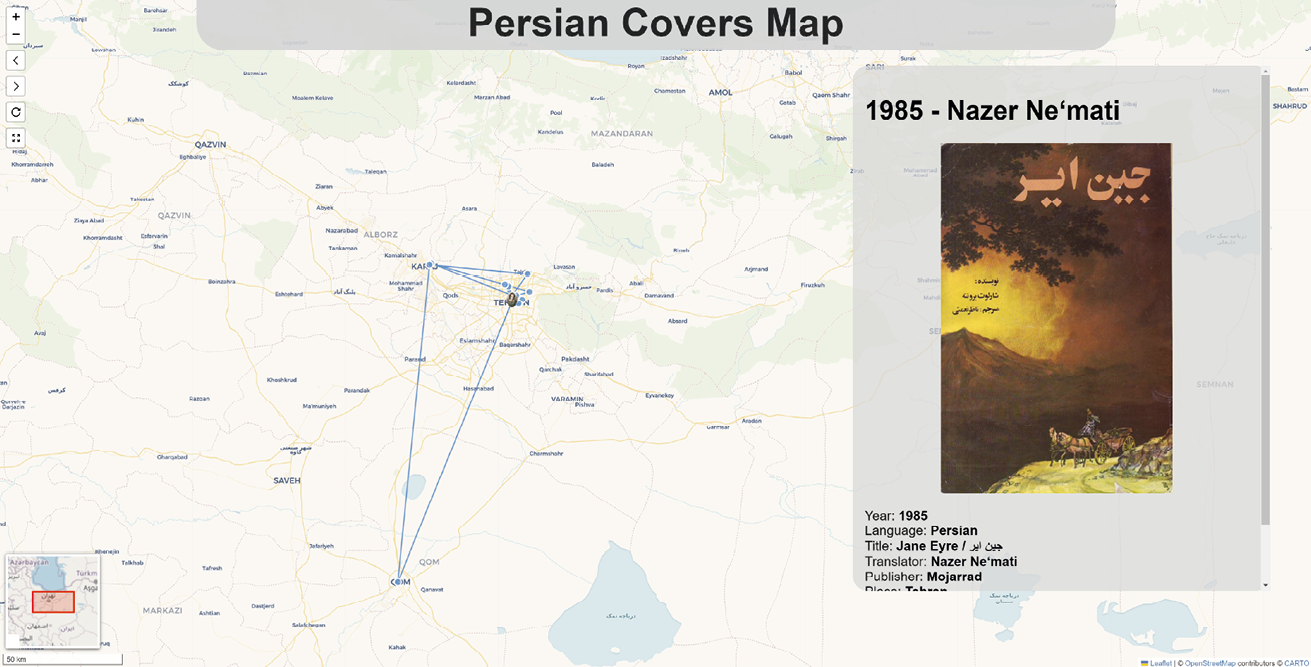

The Persian Covers Map https://digitalkoine.github.io/persian_storymap/ Researched by Kayvan Tahmasebian; created by Giovanni Pietro Vitali and Simone Landucci

8. The Translatability of Love: The Romance Genre and the Prismatic Reception of Jane Eyre in Twentieth-Century Iran

© 2023 K. Tahmasebian & R. R. Gould, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0319.12

My love has sworn, with sealing kiss,

With me to live — to die;

I have at last my nameless bliss.

As I love — loved am I!2

In the field of reception studies, Walter Benjamin’s description of translation as emerging from the original’s survival (Überleben) highlights the infinite variety of metamorphoses that literary texts could undergo in their worldly circulation. ‘For a translation comes later than the original,’ Benjamin asserts, ‘and since the most important works never find their chosen translators at the time of their origin, their translation marks a stage in their continuing life [Fortleben].’3 Benjamin remarks that the work’s capacity for continuing its life in subsequent translations, its Übersetzbarkeit (translatability), originates in a potential inherent in the work itself. Benjamin’s account of translatability as the continued life of a literary text is instructive. Translation can be regarded as a process that brings forth a text’s potential life, albeit in different ways every time it is undertaken. If any literary text can be translated in innumerable ways then, in theory, translation can be made to encompass any juxtaposition of two or more texts in any relation. The multiplicity of translation’s modes of continued life is attested to by the broad spectrum according to which translations vary, ranging from strictly interlinear to free translations. By studying translations in terms of the ways in which they survive following their migration into other languages, we can better apprehend the variety and evolution of readerships that these translations generate across times and places.

The present chapter explores the Persian lives of Charlotte Brontë’s novel Jane Eyre (1847). As we explore the possibility of comparative reading in a global context and across genres generated through a fundamentally different (premodern and non-European) poetics, we show how the nineteenth-century British novel continues its life in the Persian language and, most particularly, how it was received by Iranian readers according to the well-established tradition of the Persian romance that has given world literature some of its most famous lovers, including Layli and Majnun, Khosrow and Shirin, and Yusof and Zolaykhā. Beyond simply studying the reception of the Persian Jane Eyre, we illuminate the romantic potentialities of the narrative that are revealed through its exposure to a discourse of love that developed in a radically different cultural context and according to literary typologies that are without counterpart in the source literature.

Our method of reconstructing the reception of the Persian Jane Eyre was developed through extensive work on the numerous translations of the novel into Persian within the framework of the Prismatic Jane Eyre project. The prismatic metaphor of translation takes a pluralistic stance towards the relation of the original and the translated. Through the prism of translation, the text is dispersed and redistributed across languages, genres, cultures, and temporalities. In contrast to communicative translation paradigms that evaluate the product in terms of its faithfulness to an original, prismatic translation explores the creative ways in which the translated text deviates from the original. Regarding translation ‘as a release of multiple signifying possibilities’ instead of ‘producing a text in one language that counts as equivalent to a text in another’,4 the prismatic approach is concerned with emancipating dormant interpretive and performative potentialities of the text when they are disjoined from the original language and context.

A prismatic examination of the reception of Jane Eyre in Persian will show how this multi-layered novel, with its interwoven strands of realism, romance, gothic, social-comment novel, governess novel, Bildungsroman, and spiritual autobiography,5 undergoes a dispersion through translation whereby the novel’s romance dimension is intensified by translational interventions. This approach grew out of our discovery that a considerable share of Jane Eyre’s Iranian readership over the past seventy years has been constituted by readers who consider the novel as a work of ‘love literature [adabiyāt-e ʿāsheqāna]’ a term that references an established genre of Persian literature. Our survey of around thirty translations into Persian of Jane Eyre completed over the course of seventy years draws a trajectory whereby the Persian Jane evolved from the archetypal beloved of a Victorian romance into the independent resolute character favoured by feminist discourses in contemporary Iran, who nevertheless retains the characteristics of the archetypal Persian lover.6 Over the course of seventy years, Persian translations of the English novel have evolved from early abridged translations that foregrounded the romance constituents of Jane Eyre, and which selectively and strategically rewrote the story in Persian, to more realistic refashionings that highlight the protagonist’s education and autonomy, represented by elaborate paratextual devices in the most recent Persian versions.

Our reception-oriented reading considers how Jane, Rochester, and St John Rivers are perceived in their interrelations, according to concepts that construct the Persian discourse of love such as the lover’s absence or separation (ferāq), the lovers’ union (vesāl), the dialectic of the lover’s demanding love and the beloved’s demurral or rejection (nāz va niyāz), and the beloved’s infidelity (jafā). Our discussion intersects with the study of gendered aspects of language, comparative genre studies, the sociology of translation and retranslation, world literature, and popular culture. We explore how the Persian readership of Jane Eyre actualises the romantic potentialities of the text by filling its ‘gaps’ and ‘indeterminacies’ within an established generic ‘horizon of expectation’, ably described by Hans Robert Jauss.7 Concurrently, we investigate the role of translators and publishers in forging an ‘interpretive community’ that demands particular modes for reading literary texts.8

Publishing Contexts for Jane Eyre in Iran

Jane Eyre enjoys a special place within the modern Persian literary system. The novel has been extensively read and appreciated by generations of Iranian readers and has occupied a central role in Iranian English language-learning programs, both as supplementary reading material and in Iranian university curricula for English literature. Brontë’s novel has existed in Persian ever since 1950, in the translation of Masʿud Barzin. Since then, over thirty translations have been published. This abundance of Jane Eyre’s retranslations into Persian contrasts with a striking paucity of critical literature on the novel in Persian. Iranian scholarship on the novel is restricted to merely two scholarly articles: a New Historicist reading of racial ideology in Jane Eyre and an analysis of connotations in several translations of the novel into Persian.9 Joyce Zonana’s 1993 feminist reading of Jane Eyre has also been translated into Persian.10

Much of the online Persian material about Jane Eyre, especially on online Iranian booksellers, is directly translated from English sources. Reviews and notes to the novel that are written originally in Persian identify it as a ‘love story [dāstān-e ʿāsheqāna]’.11 In a note on an abridged Persian translation, a reviewer maintains that the novel narrates a ‘love adventure [mājarā-ye ʿāsheqāna] full of ups and downs’.12 Another reviewer classifies the novel as a classical romance novel (roman-e ʿāsheqāna) replete with ‘suspense, love, absence, union [vesāl], failure and patience’.13 An Iranian website introduces the novel as the third in a list of ‘ten love novels everyone should read’, a list that also includes Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina, Proust’s In Search of Lost Time, Austen’s Pride and Prejudice, Brontë’s Wuthering Heights, Flaubert’s Madame Bovary, F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby, Pasternak’s Doctor Zhivago, Pushkin’s Eugene Onegin, and Goethe’s The Sorrows of Young Werther.14 Jane Eyre is routinely included in other similar listings of the greatest love stories in world literature in Iranian media.15 This coverage attests to the public visibility of the novel, alongside the popularity of its film adaptations.16

Jane Eyre’s popularity in Iran is also revealed by the large number of its retranslations. The title has been translated, either full or abridged form, by over thirty different translators.17 Each translation/rewriting has appeared in several prints runs. Jane Eyre has also been published by publishers based in Qom, Mashhad, Isfahan, and Tabriz, provincial cities that comprise only a marginal share of the book market in Iran. While the title existed for two decades in only one translation, the first-ever Jane Eyre in Persian by Masʿud Barzin (1950),18 since the 1979 Iranian revolution, around thirty other retranslations have since appeared, including in abridgements, as in Fereidun Kar’s translation,19 or translations of Jane Eyre rewritten by other writers, as in Maryam Moayyedi’s Jeyn 'Eyr (2004),20 which translates Evelyn Attwood’s simplified version of the novel.

Plagiaristic translations are also found among the thirty translations. For example, during our work for the Prismatic Jane Eyre project, we compared randomly selected excerpts of some translations with the original. Marzieh Khosravi’s 2013 translation21 was revealed to be a complete word-by-word copy of Mohammad-Taqi Bahrami Horran’s Jeyn 'Eyr (1991).22 The absence of copyright regulations, the indeterminate legal situation of publications, and the lack of quality checks have contributed to a chaotic market. European classics are frequent targets for such plagiarist acts. Further adding to their suitability for translation in the Islamic Republic of Iran, Victorian novels like Jane Eyre do not usually contain material — such as sex, drinking, extra-marital affairs, and obscenities — that often trigger the pre-publication reviews that are part of the government censorship apparatus, determining what can and cannot be published. For this reason, translations of Victorian novels are less likely to attract heavy government oversight. However, even for Jane Eyre, censorship has not been entirely avoided. References to ‘wine’ in the original are altered in Persian translation. In the version by Bahrami Horran, ‘an aromatic drink [nushidani]’ and ‘syrup [sharbat]’ is substituted for ‘wine’ in the following passage:

Something of vengeance I had tasted for the first time; as aromatic wine it seemed, on swallowing, warm and racy: its after-flavour, metallic and corroding, gave me a sensation as if I had been poisoned.23

In recent years within Iran, the problem of plagiaristic translations has attracted critical and journalistic attention.24 Alongside full plagiarism, some translations of Jane Eyre show traces of having been compiled from a range of past translations. Plagiaristic re-translations of the so-called classical ‘masterpieces’ benefit both the publisher and the pseudo-translator. They are attractive to those who desire irresponsibly to see their names on the book covers as translators — literary translation is a prestigious occupation in Iran today, though it is not rewarding in terms of payment. Another common reason for fully plagiaristic published translations is that they may enhance the curriculum vitae of those aspiring to university positions. Such inauthentic works are expedient to publishers who must publish a certain quota of books annually in order to retain their permission to publish. Reprinting earlier retranslations of a popular novel, especially those which are no longer in print, is a profitable means of producing a book without paying for translator’s rights. It is even common for the pseudo-translator to pay the publisher, requesting that their name appear on the cover as the translator of such and such a masterpiece of world literature.

Jane Eyre in Persian: Three Case Studies

We have excluded plagiaristic translations as well as translations from rewritten or abridged Jane Eyres from our immediate purview. Our examination focuses instead on Barzin (1950), the first ever translation of the novel into Persian, Bahrami Horran (1991), a best-selling translation of the novel reprinted many times, and Reza’i (2010),25 a recent, accurate, and high-quality translation. Reza’i’s translation combines accuracy with detailed paratextual information so that the reader can better understand the historical, biblical, and literary allusions central to Jane Eyre, and come to appreciate the narrator as a remarkable educated woman.

Our selection is also informed by the reputation of the three translators, who are among the most prolific and professional of all of the Persian Jane Eyre translators. The first, Masʿud Barzin, was an Iranian journalist, the ex-director general of the former National Iranian Radio and Television (1979), the first director of the Iranian Trade Union of Writers and Journalists, cultural coordinator in the Iranian embassy in India, and the general director of the public relations office of Farah Diba, the Pahlavi queen prior to the revolution. Barzin also translated Oliver Twist (1837–39) and Gone with the Wind (1936) and has compiled a glossary of journalistic terms in Persian. Mohammad-Taqi Bahrami Horran has translated around ten works, mostly literary, such as Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (1865) and Le petit prince (1943). Reza Reza’i, formerly a champion of the Iranian Chess National Team, has published around thirty translations, mostly literary, of Jane Austen, the Brontë sisters, and George Eliot.

The popularity of Jane Eyre also resonates with the popularity of Daphne du Maurier’s novel, Rebecca (1938) in Iran. Rebecca’s plot is so similar to that of Jane Eyre that it has been understood by some as an adaptation of Brontë’s novel.26 Both du Maurier’s novel and its film adaptation by Alfred Hitchcock (1940) were popular classics for Iranian readers and movie-goers. Du Maurier’s novel has appeared in at least twenty-five different translations into Persian since the first translation by Shahbaz in 1954. It also appears in the above-mentioned Persian list of the most popular love stories of world literature.

The published Persian translations of Jane Eyre foreground romantic aspects, beginning with the cover images selected for Persian versions of the novel. Cover artists for these editions employ familiar melodramatic symbolism pertaining to marriage and love, with motifs of couples, hearts, and roses, as you can see by exploring the Persian Covers Map. One of the covers, of Afshar’s 1985 translation,27 is exemplary in this respect: it depicts a pair of female hands, presumably Jane’s, holding to her breast an image of what appears to be Thornfield Hall, with a heart imprisoned behind its columns. Such cover images played a decisive role in shaping Jauss’ horizon of expectation for the Iranian reader. They bring into focus the love between Jane and Rochester while barely making reference to other aspects of the protagonist such as her steadfast and independent character.

Translators’ prefaces help us see how the novel is introduced to the Iranian reader. Most of the prefaces to translations of Jane Eyre consist primarily of a short biography of the author. Barzin adds a prefatory note in praise of Brontë’s genius (nobugh).28 He admits that he has abridged the novel, but insists that ‘nothing of the matter [‘asl] of the story is lost. I have removed only marginal parts [havāshi] and passages of merely second-order significance [daraja-ye dovom] in this masterpiece which do not please the Iranian reader’.29 The ‘marginal and less significant’ removed content, however, includes the allusive texture of the novel (to the Bible, to literary texts, to fairy tales) as well as the protagonist’s reflections upon her feelings and her moral progress. With these parts removed, the Bildungsroman aspects of the novel are diluted. Bahrami Horran’s preface emphasizes the autobiographical nature of the book, not in the sense intended by the ‘autobiography’ in the original title (Jane Eyre: An Autobiography) but by identifying Jane the protagonist with Brontë the author.30 The identification of Jane and Charlotte is evident also in Barzin’s emphasis on Brontë’s ‘genius’ which transformed her from a poor girl into an affluent writer in ‘a lifetime battle with poverty and hardship’, as indicated in the biography provided for Brontë on the back cover of Barzin’s translation. All Persian translations have removed ‘an autobiography’ from the original title and only a few translations (Ebrahimi, Bahrami Horran, Reza’i) point to the writer’s pseudonym, Currer Bell, in their prefaces.

As regards the transliteration of Jane’s name in the title, all translators invariably translate it as جین ایر (pronounced jeyn air) with the exception of Barzin, who changes the title to yatim (orphan), with the Jane Eyre as the subtitle spelled unconventionally in Persian, ژن ئر. The spelling looks strange to an Iranian reader, with the ‘J’ transcribed, in a French fashion, to be pronounced as /zh/ and ‘Eyre’ transcribed in a script that resembles no Persian word and which instead looks like Arabic (without however corresponding to any existing Arabic spelling). Persian and Arabic words do not begin with a joined hamza. The change of the protagonist’s name resonates with the translator’s emphasis on Jane/Charlotte’s genius; zhen is a homophone to zheni, a calque used in modern Persian for French géni (genius). Barzin’s cover is embellished with a bleak expressionist-like depiction of a female figure which could be ascribed to Jane Eyre’s period at Lowood School (Figure 13). The artist is unknown. The cover art echoes Fritz Eichenberg’s wood engravings for the 1943 Random House edition of the novel, although Eichenberg’s depictions differ in many respects.

Fig. 13 Cover image of Jeyn 'Eyr, trans. by Masʿud Barzin (Tehran: Maʿrefat, 1950)

In this earliest translation of Jane Eyre into Persian, the author/protagonist’s genius consists in the moral uprightness of her narrative and her ‘interpretation of social problems’.31 No paratextual aspect of this first translation of Jane Eyre foregrounds the romantic characteristics of the novel. The protagonist’s equilibrium between passion and reason, and between romantic and realist narrative modes, is highlighted instead. Thus, the first image of Jane that presented to the Iranian reader was less concerned with her romantic life than with her gender-specific capacity to transform her life of poverty and weakness into one of joy and strength, which made her a role model for modern Iranian readers.

Barzin’s is the only translation of Jane Eyre into Persian until the 1979 Iranian revolution, at which point over thirty translations appeared in the period up to 2017. Meanwhile, the novel’s pattern of reception has acquired the markers of the love literature (adabiyāt-e ʿāsheqāna) genre. Reza’i introduces Jane Eyre as a work at the ‘summits [qolla-hā]’ of classical world literature.32 The translator focuses on the element of balance in the novel by recognising the writer’s style in an intermediary state between realism and romanticism. He characterises the heroine as ‘an ordinary-looking girl with a sublime spirit, who resists the ties of the world without losing faith in the foundations of her ethics and beliefs [osul-e akhlāqi va eʿteqādi]’.33 At the same time, he describes the novel as a story of ‘love, happiness and suffering, duty and morals, patience and victory, separation (ferāq) and union (vesāl)’.34 Afshar writes that the most distinguished feature of this ‘pleasant romantic story [dāstān-e romāntik]’ is the chastity of Jane and Master Rochester’s love’.35 Ebrahimi’s translation appeared as the first in a book series published by the publishing house Ofoq under the title ʿAsheqāna-hāye kelāsik, or ‘classical romances’. Other titles in this series include Jane Austin’s Sense and Sensibility (1811), Emma (1815), and Pride and Prejudice (1815), Honoré de Balzac’s Eugénie Grandet (1833), Emily Brontë’s Wuthering Heights (1847), Louisa May Alcott’s Little Women (1868), Jean Webster’s Daddy-Long-Legs (1912), Lucy Maud Montgomery’s The Blue Castle (1926), and Annemarie Selinko’s Désirée (1951).

The romantic strand in the popular reception of Jane Eyre first captured our attention during our work on Jane Eyre’s prismatic Persian translations, as we saw that a considerable number of translations target the typical readers of classical Persian romances, and of other romantic literature. It has been argued that popularization of discourses is better thought of in terms of recontextualization than simplification.36 The Iranian recontextualization of Jane Eyre as a popular romance occurs within a framework in which translations contribute to reclassifying the nineteenth-century British novel within an already established genre of adabiyāt-e ʿāsheqāna. Many of the simplified or abridged Persian versions of Jane Eyre recalibrate the narrative into popular romance frameworks. We will see how the tendency of the modern Persian poetic system to define literary genres by theme contributes to such genre shifts from the original to the translated Jane Eyre. In the classical Persian typology, poetic sub-genres are defined in terms of the themes developed in the poem. Examples include the marsiyya (elegy), mofākhara (boasting poems), monāzara (dialogue), shahrāshub (complaints against cities), habsiyya (prison poem), monājāt (prayer), shekvā (complaint), hajv (satire), and madiha (panegyric).

The socio-political implications of introducing world literary masterpieces through distorted translations have been explored by the Iranian writer Reza Baraheni, who contends that such translations, abridged or expanded, intensify the aimlessness and alienation intrinsic to any translation of ‘Western’ literary and philosophical work into Persian.37 Baraheni maintains that Iranian readers’ alienation has not been resolved by post-revolutionary publishing policies in the so-called campaign against ebtezāl (superficiality). He identifies three strands in the Iranian publishing industry that transport readers beyond their objective socio-historical circumstances, two of which are comprised of translations. First, shāhābādi (literally, ‘land of the shah’) translations, a reference to the pre-revolutionary name of the street called after the Islamic Republic (currently Jomhuri Eslami Avenue) in Tehran, once the site of the most concentrated complex of Iranian publishers; second, expansionist translations (explained below); and third, historical romances. Baraheni uses the term shāhābādi to refer to the publishing industry that republished masterpieces of world literature in abridged and simplified editions in tens of thousands of copies and with a vast distribution network.

While the shāhābādi type of translations reduce the complexity of the original, expansionist translations rewrite the original by drawing on the translator’s imaginative interventions. Instead of condensing the original, expansionist translations add to it by filling the gaps. This ‘expansionist [maktab-e bast]’ type of translation is known to the Persian reader by the name of its most renowned practitioner, Zabihollah Mansuri (1899–1986). Once a legendary Iranian translator of popular literature, Mansuri’s translations have been extensively criticised for their infidelity and their imaginary rewritings of the original to the point of devising a new original text. Baraheni’s third category is comprised of popular historical novels of Iranian kings and European monarchs such as Napoleon and Russian Tsars that function, according to Baraheni, to satisfy the unconscious thirst of post-revolutionary bourgeois readers for the restoration of the Iranian monarchy. These three strands generate an escapist literature that impedes the establishment and growth of a modern national literary consciousness by bombarding national literature with imprecise and inferior translations.

While the role of so-called expansionist translations of European novels in diminishing the Iranian aesthetic is undeniable, it is equally important to view these texts as gateways to a more serious literature for many Iranian readers. The remainder of this chapter turns to the potential modes of being that these translations, however imperfect and unfaithful they may be, suggest for Jane Eyre in its global journey across world literary genres. For this purpose, we first introduce the Persian romance tradition to examine the context within which Brontë’s novel was received and categorised by Iranian readers as they integrated the text into their generic horizons of expectation.

Modern Iranian Romances and Serialised Love Stories (pāvaraqi)

The sub-genre of dāstān-e ʿāsheqāna (love story) has always maintained a formidable presence in modern Persian literature. Adventure romances were among the first translated works from European literatures into Persian as early as the late Qajar era, for example, Prince Mohammad Taher Mirza Eskandari’s translations of Alexander Dumas’s Le Comte de Monte-Cristo (1895) and Les Trois Mousquetaires (1899). Before that, Iranian picaresque narratives known as rend-nāma, after the figure of the profligate (rind), which dates back to medieval Sufi literature, delighted Iranian readers. They were published in lithographs for the private use of the literate elite and for public readings for the illiterate in public spaces such as coffee-houses. Folk romances such as Samak-e ayyār [Samak the Knight-errant], transmitted orally and transcribed during the 12th century, and Amir Arsalān-e nāmdār [The Famous Prince Arsalan] were read to the Qajar ruler Nasser al-Din Shah and were favoured by ordinary people as well. More sophisticated picaresque prose stories, known in Persian and Arabic as maqāma, and marked by elaborate mannerisms, lacked the popularity of these romances. These folk romances are comparable to European chivalric romances in that both are patterned after a quest: the lover must undergo several trials to gain the beloved’s favour and union. Early popular romantic legends, such as Mohammad Baqer Mirza Khosravi’s Shams va Toghrā' (1899) were written in imitation of both Iranian folk legends and the early translated European novels.

Early Iranian popular romances, such as Sheykh Musa Nasri’s ʿEshq va saltanat [Love and sovereignty] (1881) or Mirza Hasan Khan Badiʿ’s Sargozasht-e Shams al-Din va Qamar [Tale of Shams al-Din and Qamar] (1908) were characterised by a double plot of razm (battlefield) and bazm (feast). The double epic-romantic structure imitates the most popular love stories in Ferdowsi’s Shāhnāma [Book of Kings], including that of Bijan and Manijeh in which an account of the brave deeds and battles of the male prince, Bijan, is given alongside accounts of his love affairs with the female princess, Manijeh. These stories were recited by public oral storytellers (naqqāl) or were illustrated in sophisticated manuscripts for the court. ʿAbedini has demonstrated how late Qajar romances distracted the masses during the turbulent days of the Iranian Constitutional Revolution (1905–1911) with ‘exciting stories of love and war of the princes who had lost their crowns’ against the background of Iran’s past glory, thus fulfilling the ideological function of generating sympathy with the Qajar dynasty just as it was losing its grips on monarchical power.38

With the decline of the Qajar monarchy, these romances embraced more nationalist causes in compliance with the modernist-nationalist cultural policies of Reza Shah (1925–1941). The most remarkable popular romances for this period are rooted in Iran’s ancient pasts and focus on Achaemenid, Parthian, or Sassanid kings. Under the guise of a pseudo-historical account of the wars and loves of Cyrus the Great, Alexander, Ardeshir, and Yazdgerd, the reasons for Iran’s power and moral decline are sought. Dreams for a civilizational restoration are elaborated in historical novels (romān-e tārikhi), such as ʿAbd al-Hoseyn Sanʿati-zadeh’s Dāmgostarān [Mouse-catchers] (1920–1925), Haydar ʿAli Kamali’s Mazālem-e Tarkān Khātun [Lady Tarkan’s plea for justice] (1927), ʿAli Asghar Rahim-zadeh Safavi’s Shahrbānu and Hoseyn Masrur’s Dah nafar Qezelbāsh [Ten Qezelbash soldiers] (1948). More realist and historicist dimensions are also observed in Mortaza Moshfeq Kazemi’s Tehrān-e makhuf [Horrible Tehran] (1926), the first Iranian social novel.

Since the 1940s, with the spread of newspapers, love stories circulated in serialised forms in weekly magazines known as pāvaraqi.39 These serialised love stories of Hoseynqoli Mostaʿan (with twenty stories) and Javad Fazel (with more than forty stories) attracted a huge number of readers to the extent that, according to ʿAbedini, ‘the weekly magazines Omid, Sabā, Taraqi, Tehrān Mosavvar and Ettelāʿat Haftegi that published them were printed in five to fifteen thousand’.40 The first translated pāvaraqi was published in Ettelaʿ magazine in 1936 by Mohammad Hoseyn Forughi under the title, Jorj-e Engelisi ʿāsheq-e mādmovāzel Mārti-ye Pārisi [English George in love with Mademoiselle Marti from Paris]. These are the best examples of modern Iranian escapist literature with loosely plotted stories and stock expositions, complications, climaxes and resolutions of a love affair between male and female characters who only change names as they appear in different stories. Substantial variation in the plot structures was rare. Authors entertained their readership by adhering to the same conventional protocols between the author and the huge mass of its readers.

The publication of these extraordinarily popular serialised romances coincided with the political oppression that followed after the American and British-led coup in 1953. The previously mentioned ‘expansionist’ strand of translation, represented by Zabihollah Mansuri’s works, grew out of this phenomenal cultural market. His serialised column, ʿOshāq-e nāmdār [Famed Lovers] delighted Iranian readers of the popular magazine Sepid va Siyāh for eight years. His works, transgressing the boundaries of translation and authorship, are among the most widely read by contemporary Iranian readers. Not only in fiction but also in poetry, Iranian popular magazines of the 1950s and 1960s were haunted by the romance genre. Fereidun Kar, one of the most important poets working within this popular strand, also translated Jane Eyre into Persian (1990). With Eʿtemadi’s twenty-eight best-selling love novellas, the trajectory of the genre of love story writing (ʿEshqi-nevisi) had reached its peak.

This trend was abruptly stopped with the 1979 revolution in Iran. The rise in the publication of classics such as Jane Eyre in the eighties and nineties should be understood in the context of the anti-superficiality (zedd-e ebtezāl) campaigns of the post-1979 revolutionary cultural milieu. In the absence of multitude of love stories, translated classics and their revival as dāstān-e ʿeshqi offered a way to preserve the huge Iranian romance enthusiast market that had developed prior to the revolution. Although a more conservative form of ʿeshqi-nevisi was revived in the late nineties after the reformist opening in the Iranian political sphere with writers such as the best-selling Fahimeh Rahimi with twenty-three novels, a considerable number of romance readers were drawn to reading translated nineteenth century European novels with romantic overtones.

The Problem of a Comparative Generic Classification

The popular reception of adabiyāt-e ʿāsheqāna (love literature) is rooted in a lyric sub-genre of classical Persian poetry, named manzuma-ye ʿāsheqāna (romance verse), which recounts love affairs between an amorous couple in the masnavi (couplet) form. The most canonical Persian romances are Nezami Ganjevi’s Layli va Majnun (1188), Khosrow va Shirin (c. 1175–76), and Seven Beauties (c. 1197), and Jami’s Yusof va Zolaykhā (c. 1482). Each of these narratives recounts the affairs of the world-famous literary lover figures.41 The exact number of these manzumas is unknown but around six hundred extant manuscripts have been identified, mostly in verse.42 In classical Persian literature, poetic love narratives (ʿEshq-nāma) exist either in the lyric form of the ghazal (as in Hafez’s poetry) or in verse romance narratives considered to have originated in the ghazal.43 The Iranian scholar Hasan Zolfaqari relates the ghazal to the manzuma, on the grounds that ‘in the ghazal, the concept of love is expressed implicitly; however in a manzuma-ye ʿāsheqāna, the same theme is made explicit and extended in the form of narrative.’44

The tradition of Persian romance verse narrative has itself flourished across spatial and temporal boundaries in its global circulation. The first significant contribution to the Persian romance tradition, Fakhr al-Din Asʿad-e Gorgani’s Vis va Rāmin (c. 1050) is adapted from an earlier Parthian love story.45 A century later, this work was translated into Georgian prose by Sargis Tmogveli under the title Visramiani, and this rendering later helped scholars seeking to reconstruct details of the original Persian.46 The form reached its maturity with Nezami Ganjevi’s Layli va Majnun and Khosrow va Shirin. These two classics of Persian verse romance received many imitations (nazira), adaptations (eqtebās) which collectively constitute a rich body of classical Persianate love stories in verse, extending from South Asia to the Balkans.47 The genre is also popular in other parts of the Persianate world, as seen as in the Kurdish oral legends of charika, Azeri ʿāshiq’s sung narratives and in the Armenian poems of Sayat Nova in the Caucasus, and countless adaptations of Persian romances into Urdu and other Indian languages in South Asia.

Persian verse romances pose a challenge to comparative poetics in terms of their literary generic classifications. Attempts have been made by Iranian scholars to categorise these verse narratives according to generic frameworks borrowed from European poetics. Cross-categorization is significant when we consider that famous dramatic works such as Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet and Anthony and Cleopatra are at times introduced as ʿEshq-nāma, following the convention in the modern Persian poetic system of determining the genre membership of a literary work according to its theme. Connecting the term ‘lyric [ghenāyi]’ to European literary theory, the Iranian literary critic Sirus Shamisa categorizes these manzumas as ‘narrative lyric [ghenāyi dāstāni]’.48 As Shamisa recognises, European lyric poetry deals with an individual’s inner desires and emotions, hopes, failures, and ambitions. However, the term ghenāyi in the Persian literary system originates in an Arabic literary typology and encompasses a diverse range of themes (mazāmin) such as ‘panegyric (madh), satire (hajv), elegy (marsiyya), complaint (shekvā), separation (ferāq-nāma), prison poem (habsiyya), pride poem (mofākhara), oath (sowgand-nāma), praising the wine-bearer (sāqi-nāma), prayer (monājāt-nāma), happiness (shādi-nāma), the Prophet’s ascension (meʿrāj-nāma), praise songs (moghanni-nāma), debate poems (monāzara), complaints against cities (shahrāshub), turning away from the beloved (vāsukht), modesty (voquʿ), and declarations of love (taghazzol).’49 Romance verse (manzuma-ye ʿāsheqāna) is distinguished because it is inclusive of all other ghenāyi themes, that is, some or all of the just-mentioned themes can be included in a manzuma.

Debates around the classification of Persian romances arise when a non-Iranian generic classification system, such as the tripartite typology of narrative (epic), lyric, and dramatic, is taken as the comparative measure. With this pre-supposition, it is not easy to classify a manzuma either as lyric or as narrative, because it can be both. A manzuma is narrative and is also lyric when the term is understood as ghenāyi to refer to poetic forms that deal with individual feeling and inner life. The problem arises from the translational identification of European lyric and the Arabo-Persian ghenāyi. Both words have musical resonances, ‘lyric’ in its original Greek reference to lyre that accompanied the recitation of poems, and ghenāyi from Arabic ghinā (‘to sing’), a term used for the recitation of poems that were to be performed in musical accompaniment. Shamisa adds the adjective dāstāni (narrative) to ghenāyi (lyric) in order to bypass the problematic identification of the two terms. Attempts to classify manzuma according to a European typology, however, end in ambivalence between the lyric and dramatic in the light of the fact that lyric poetry in European literature is generally non-narrative.

The debate around the generic cross-categorization of Persian romances reveals a significant structural characteristic of the genre in fluctuation between epic and lyric, and between the communal and the individual. This structural duality is reflected in the dual structure of the modern love stories comprising descriptions of razm (battles) and bazm (love). As regards our study of Jane Eyre through the lens of Persian romances, the fact that Persian manzumas can only be called lyric when lyric elements permeate and interrupt the narrative elements resonates with the duality of romance and realism that is essential to Brontë’s novel. ‘The romantic, concerned with life’s more extraordinary moments, including the passionate, is represented by Jane and Rochester’s relationship,’ argues Zoë Brennan, adding the caveat that ‘passion is bridled to morality as Brontë attempts to include it in the realm of everyday. So, the novel can be said to take a realist stance, presenting the domestic and the everyday.’50

Having presented a synoptic history of the Persian romance, the next section reads Jane Eyre through the lens of Persian romances, with particular attention to their structural characteristics. We will see how the novel has been received by the Persian reader whose ‘horizon of expectations’ is shaped by romantic forces that eclipse all other generic dimensions of the novel, including the Bildungsroman, spiritual autobiography, and gothic.

Jane Eyre as a Persian Romance

Persian love stories progress according to a consistent pattern: A falls in love with B; A and B are initially in a state of separation; A seeks union with B and has to overcome certain obstacles and challenges; the story ends either happily with A and B united, or tragically with A and/or B dead. As regards Jane Eyre, the romantic component revolves around a love triangle with Jane and Rochester in mutual love and St John Rivers in love with Jane. Lovers in Persian romances can be grouped according to the degree of agency they show with respect to their beloved. While in Nezami’s Khosrow and Shirin, both Khosrow and Shirin are actively engaged in the game of love — they plot and act to resolve the problems on their way to union — the character of Majnun in his Layli and Majnun is the archetypal passive lover of Persian literature, who remains satisfied with a mere image of the beloved until his tragic end in madness on the grave of his beloved Layli, after she has died in despair.

From this point of view, Jane Eyre’s conduct and character as a beloved is comparable to Shirin: both have preserved a balance between their passion and their reason. Sattari describes Shirin as ‘the symbolic face of a woman in love who refuses to transgress morality, mixing her passion with chastity (ʿeffat).’51 For a substantial proportion of Iranian readers, Jane’s refusal of Rochester’s proposal to leave England together and live with him in Southern France as his wife would recall Shirin’s resistance to Khosrow’s seductions for premarital pleasure.

The romantic triangle of Shirin, Khosrow, and Farhad in Nezami’s romance also parallels that of Jane, Rochester, and St John in Jane Eyre. The double pattern of satisfied and disappointed lovers is present in both texts, under the guise of Khosrow and Farhad in Nezami and Rochester and St John in Brontë, respectively. St John’s austere perseverance in his love for Jane and his journey to India is echoed in Farhad, the disappointed lover who dies with the same sense of vocation, as a sculptor cutting the mountains and dreaming of Shirin. Furthermore, Rochester and Khosrow are parallel figures; they both play the role of the capricious aristocratic lover in these love triangles in contrast with the more responsible figures of Farhad and St John. Rochester’s mad wife, Bertha, is as much a marital obstacle to Rochester’s passion for Jane as is Khosrow’s wife, Maryam, the Roman Emperor’s daughter. Also, Khosrow’s flirtations with Shekar-e Esfahani in order to make Shirin jealous is reminiscent of Rochester’s teasing of Jane by showing affection for Blanche. Nezami’s romance ends with the death of lovers, with Shirin committing suicide in the arms of her lover, murdered by his son. However, Khosrow’s seclusion in a fire temple (ātashkada) after yielding all his power to his son is similar to the scene near the end of Jane Eyre, with a blind handicapped Rochester in Ferndean after his Thornfield property has been burnt in the fire initiated by Bertha.

These parallels between different roles and positions do not constitute an adequate basis for systematic comparison. However, they point to the horizon of expectations that Iranian readers bring to a novel like Jane Eyre when it is introduced to them as a ‘classical romance [ʿāsheqāna-ye kelāsik]’, as in Ebrahimi’s 2009 translation, which formally announces the genre membership of the Persian Jane Eyre through the name of the book series to which it belongs. Such converging horizons can also be found on a morphological level. In recent years, several studies have been undertaken by Iranian scholars on the morphology of Persian romances. Most of these studies are inspired by Vladimir Propp’s approach to the structural elements of Russian folktale narratives.52 For example, through an examination of twenty-two Persian romances, Va‘ezzadeh introduces the Persian manzuma as a distinct narrative genre with an initial situation, twenty-two narrative functions and five main characters.53 Correspondingly, the narrative of Jane Eyre could be reconstructed in a way that reflects its intersection with the classical Persian romance, with Rochester and Jane as ‘the lover [ʿasheq]’ and ‘the beloved [maʿshuq]’, Rochester’s marriage as ‘the obstacle’, Bertha as ‘the villain’ and no ‘helper’ identified. Va‘ezzadeh recognises three concluding patterns for Persian romances: union (vesāl), death, and the lover’s ascension to the throne and beloved’s giving birth to the lover’s child, which is interesting with respect to Jane and Rochester’s marriage in the end and Jane’s giving birth to Rochester’s son. Rochester’s regaining his lost eyesight in the end is also a familiar ending for Persian romance readers, as in Jami’s romance where Zolaykha recovers from blindness in the conclusion.

In another morphological approach to Persian romance, again through Propp, Zolfaqari distinguishes twenty narrative functions, many of which are present in the romantic texture of Jane Eyre.54 These can be enumerated as follows: 1) The lover or the beloved’s father (the king) has no child; 2) The father’s prayers bring him a child; 3) The lover is born with difficulty and grows up fast. Although these elements are non-existent in Jane Eyre, with an orphan protagonist, the pattern nonetheless reverberates throughout the novel. The difficult birth of the protagonist in the Persian romance is a condition of possibility for the story. A Persian love story must start with an improbability. The lover should enter the world with difficulty and in despair, in order for his or her existential value, and therefore the existential value of the story of his or her love, to become evident to the reader. Therefore, as a sign of a continued life (not unlike the image of the translated text with which we opened), the lover’s difficult birth at the beginning of the Persian romance suggests the chance to live, and to survive. From this perspective, Jane’s survival of the fatal epidemic at Lowood can be regarded as among the essential constituents of the romantic component of Jane Eyre despite the fact that the same episode in the original highlights an important stage in the protagonist’s spiritual progress towards an ethics of fairness and self-respect that contrasts with the doctrine of angelic humility and self-neglect adopted by Jane’s friend Helen Burns.

We have so far identified three elements of the chain of narrative incidents and functions in classical Persian manzuma in our attempt to fit Jane Eyre into that framework and to map a potentially generative misreading of the novel in Persian. To continue this thread, which interestingly places Jane in the position of the lover and not only the beloved: 4) The lovers meet and fall in love; 5) The lover gets information about the beloved (compare, for example, Chapter 13 where Rochester enquires about Jane); 6) The lovers confess their love to each other and obstacles (religious or class differences, for example) appear on the way to their marriage (compare Chapters 21–22, the declaration of love and Jane’s insistence on not being of the same social rank as her master); 7) The lover becomes sick in separation and takes refuge in the wilderness (compare Jane’s flight from Thornfield, her wandering and sickness afterward, Chapters 28–29); 8) The lover’s relatives cannot do anything to save him or her; 9) The lover’s departure for hunting (compare Rochester’s leaving Thornfield in Chapter 16); 10) The lover embarks on a dangerous trip, usually a voyage, his ship sinks and he is saved (compare Jane’s flight from Thornfield after rejecting Rochester’s proposal and being aided by Rivers family); 11) The lover enters an unknown place and is put on trial (compare Jane’s residence in Marsh End/Moor House in Chapter 28, and her tedious life in the cottage attached to the school at Morton in Chapters 31–32); 12) The lover is aided miraculously (compare Jane’s unexpected inheritance of a large fortune from her dead uncle and gaining a family, that is, her relation to Rivers family); 13) The development of minor love plots in the margin of the main story (compare Blanche Ingram’s role in Chapter 18 and Rosamond Oliver in Chapter 32); 14) The lover’s rendezvous with the beloved in disguise (compare Rochester’s meeting with Jane in a gypsy’s disguise in Chapter 19); 15) The lover is tested (compare Rochester’s questioning of Jane in Chapters 13–14); 16) The rival impedes the union (compare Bertha’s role in the novel); 17) The lover and rival struggle and the lover wins; 18) Letters and messages are exchanged between the lovers; 19) The lover isolates him/herself after having renounced all his power (compare Rochester’s isolation in Ferndean after the fire in Thornfield in Chapters 36–37; 20) Finally, the lovers either unite or die (compare to their marriage in the novel’s final Chapter).

Beyond revealing a structural truth about the novel, the one-to-one correspondences just noted map a potential misreading of the novel that translates — and which was translated — across languages and accommodated to different generic frameworks. In this regard, it is also relevant to note the translational interventions that confer continued life on the novel’s romantic aspects. Persian amorous discourse is founded on particular concepts such as the lover’s absence or separation (ferāq), the lovers’ union (vesāl), the lover’s demanding and beloved’s demurral (nāz va niyāz), and the beloved’s infidelity (jafā) that are fostered through the millennium-old tradition of adabiyāt-e ʿāsheqāna (romance literature). Iranian translators’ use of these terms contributes to the prismatic recontextualization of Jane Eyre as a Persian romance.

For example, the concept of ferāq, the lovers’ state of separation in Persian romances, is a necessary stage in the maturation of carnal desire into a spiritual love. Reza’i translates ‘separation’ in Rochester’s consolation to Jane, ‘and you will not dream of separation and sorrow to-night; but of happy love and blissful union’ (end of Chapter 26) as ferāq.55 Another instance is the figure of the unfaithful beloved (mahbub-e jafā-kār), a ubiquitous object of the lover’s complaints in classical Persian poetry. In the following excerpt of Chapter 11, which describes a song sung by little Adèle, Reza’i translates ‘perfidy’ and ‘desertion’ as jafā and ‘the false one’ as mahbub-e jafā-kār:56

It was the strain of a forsaken lady, who, after bewailing the perfidy of her lover, calls pride to her aid; desires her attendant to deck her in her brightest jewels and richest robes, and resolves to meet the false one that night at a ball, and prove to him, by the gaiety of her demeanour, how little his desertion has affected her.57

In addition, different motivations for the protagonist’s decisions throughout the narrative are revealed when the novel is read in light of the core concepts of love relations in Persian romances. The Persian semiotics of love regards the lovers’ relations as a dialectic of demanding and demurring (nāz va niyāz). In classical Persian manzumas and ghazals, the lover’s task is demanding (niyāz) and the beloved’s response to the lover’s demand is to pretend indifference (nāz). Dehkhoda defines nāz as ‘showing independence (esteghnā)’.58 In Sawānih al-ʿUshāq (Hardships of Lovers), an important 11th century Sufi treatise on love, Ahmad Ghazzali writes that ‘the beloved always remains the beloved, hence the beloved’s attribute is ‘independence [esteghnā]’, and the lover always remains the lover, hence the lover’s attribute is ‘lack [efteqār]’.59 The Iranian romance reader’s horizon of expectations interprets Jane’s rejection of Rochester’s proposal to live with him after the failed wedding as a reflection of the beloved’s indifference (nāz). In this case, the beloved’s indifference is only a pretence of ‘independence’ that is performed in order to blaze the fire of Rochester’s love, and to bring about their eventual marriage. It diverges from the classical Persian paradigm, whereby nāz signifies the beloved’s firm resistance of the temptation to enter into a forbidden and secret relationship.

The Language of Romance

The novel’s tendency toward romance in its Persian translations is manifested in the ways the Persian Jane loses her capacity for balancing her passion and her reasoning faculty. The Jane of Victorian England is distinguished by both her emotional intensity and her intellectual judgement. These capacities come to be revised through the heterogeneous resources of the Persian language. This revision derives in part from the limitations and difficulties of the Persian language in clarifying private emotions and feelings. The best example is the lack of clear delineation in Persian for the words ‘feelings’, ‘emotions’, and ‘sentiments’ which have no semantic delineation and are rendered by the same word — ehsāsāt — in all Persian versions of the novel.

These limitations also become evident in connection with key words in the novel such as ‘passion’. Matthew Reynolds remarks that ‘Passion’ is one of the terms in Jane’s psychomachia, in which context it battles with ‘conscience’ and ‘judgment’.60 Its meaning approximates to ‘love’, but can also be distinguished from love as more fleshly and fleeting; and of course there are other passions such as ‘rage’. Everyone notices that Jane is ‘passionate’. A remarkable part of Jane’s intellectual faculties lies in her ability to give detailed descriptions and analyses of what she actually feels and thinks. And exactly these are the parts that are subject to most of the distortions and omissions in Persian translations. These descriptions constitute part of what is usually cut in translations, as in Barzin’s. In general, the word ‘passion’ has been rendered by a wide range of words in Persian meaning ‘excitement’ (shur), ‘love’ (ʿeshq), ‘strong desire’ (tamannā) and ‘anger’ (khashm). Because of this indeterminacy, Reza’i translates ‘passion’ into redundant structures by joining two synonymous words by ‘and’. For example, in the case of ‘I had felt every word as acutely as I had heard it plainly, and a passion of resentment fomented now within me,’ Reza’i translates ‘passion’ as khashm va ʿasabāniyyat (‘anger and rage’),61 while in the case of ‘The passions may rage furiously, like true heathens, as they are’, the word is translated as shur va sowdā (‘excitement and melancholy’).62

Table 1 shows how different Persian translations of Jane Eyre interact with regard to Jane’s detailed description of her innermost feelings when she heard Rochester calling out to her in her imagination:

All the house was still; for I believe all, except St. John and myself, were now retired to rest. The one candle was dying out: the room was full of moonlight. My heart beat fast and thick: I heard its throb. Suddenly it stood still to an inexpressible feeling that thrilled it through, and passed at once to my head and extremities. The feeling was not like an electric shock, but it was quite as sharp, as strange, as startling: it acted on my senses as if their utmost activity hitherto had been but torpor, from which they were now summoned and forced to wake. They rose expectant: eye and ear waited while the flesh quivered on my bones.63

|

1 |

Najmoddini64 (1983), p. 174 |

.ناگهان احساس ناشناختهای آنرا از حرکت بازایستاندند. این حس مانند یک شوک الکتریکی نبود. ولی خیلی تند و غریب بود و روی تمام اعصاب من تاثیر گذاشت. در حالی که بدنم میلرزید چشم و گوشم منتظر ماندند |

|

2 |

.قلبم به شدت میتپید، آن چنان که صدای قلب خویش را میشنیدم، به ناگاه تپش سریع قلبم، از حرکت بازایستاد و احساسی غریب بر من حاکم شد آنچنان که قلبم را دچار لرزشی عظیم کرد. لرزشی که از حوزه قلبم گذشت و اعماق مغزم را به لرزه کشاند، این احساس مانند یک شوک الکتریکی نبود، اما احساسی کاملا غریب بود مانند یک تکان ناگهانی بود و آنچنان بر اعصابم اثر گذاشت که با آخرین تاثیر ممکنه اعصابم را به تحرک واداشت با این احساس گوشت بر روی استخوانم لرزید و نگاهم و همه وجودم به حالت انتظار باقی ماند |

|

|

3 |

.و قلب من که از چند ساعت پیش دچار هیجان شده بود به تندی میطپید، ناگهان اعصابم سست شد و عرق سردی بر بدنم نشست |

|

|

4 |

.قلبم با سرعت و شدت میتپید؛ صدای تپش آن را میشنیدم. ناگهان در اثر یک احساس توصیفناپذیر ایستاد. این احساس، که چنین اثری بر آن نهاده بود، یکباره تمام وجودم را در بر گرفت. به رعد و برق شباهتی نداشت اما بسیار شدید، عجیب و تکاندهنده بود. تأثیر آن بر حواسم به گونهای بود که گفتی منتهای فعالیت آنها تا این موقع فقط یک حالت خواب مانند بوده، حالا آنها را فراخواندهاند و آنها ناگزیر بیدار شدهاند. وقتی بیدار شدند حالت انتظار داشتند: چشم و گوش در انتظار بودند و گوشت و پوست روی استخوانم میلرزیدند |

|

|

5 |

.قلبم تند و بلند میزد. صدای تاپ تاپش را میشنیدم. ناگهان احساس وصفناپذیری قلبم را از حرکت انداخت، و این احساس نه تنها قلبم را از حرکت انداخت بلکه به سرم انتقال یافت و بعد هم در کل وجودم منتشر شد. احساسم شبیه برقگرفتگی نبود، اما بسیار شدید و عجیب و تکاندهنده بود. چنان بر حسهایم تاثیر گذاشت که گویی حسهای من تا آن لحظه فقط در حالتی شبیه به خواب بودند. حالا به این حسها ندا و فرمان میرسید که از خواب بیدار شوند. حسهایم برخاستند و تیز شدند. چشم و گوشم باز شدند و تمام بدنم به رعشه افتاد |

|

|

6 |

Rasuli (2011), p. 42665 |

. گرفت. مثل شوک الکتریکی نبود ولی خیلی تکاندهنده بود |

|

7 |

.ناگهان قلبم ایستاد؛ احساسی وصفناپذیر از قلبم گذشت، به سرم منتقل شد و تمام وجودم را فرا گرفت. احساسم شبیه برقگرفتگی نبود، اما شدید، عجیب و تکاندهنده بود. به گونهای مر ا برانگیخت که انگار قبلا در رخوت و خمودگی بودم. ذره ذرهی وجودم را از خواب بیدار و فعال کرد. هوشیار شدم، چشم و گوشم باز شد و بدنم شروع کرد به لرزیدن |

Table 1: Jane hears Rochester calling out to her in seven Persian translations of Jane Eyre:

As the table shows, Iranian translators have had problems especially with the word ‘extremities’, the material equivalent of Brontë’s ‘passion’. ‘Extremities’ has no definite counterpart in Persian. Afshar mistranslates it as ‘the field of my heart [howza-ye qalbam]’. Najmoddini and Kar omit not only the whole phrase but this entire crucial paragraph. Bahrami Horran condenses the whole phrase as ‘all my existence’ (tamām-e vojudam). Reza’i renders it as ‘all my body’.

As regards the verb ‘thrill’, the translators in Table 1 have either had recourse to explanatory phrases or have omitted the word. In the former case, the translator’s imagination plays a significant role in rewriting these descriptions of inner experience, which make the translated text read like a passionate narration of opaque inner experience rather than a precise analysis of emotions. Ebrahimi condenses the entire feeling into the phrase ‘an inexpressible feeling’. This conversely generates a sense of indeterminacy and imprecision rather than clarity of mind, thereby depriving Jane of a great part of her intellectual capacity in Persian translation. At the same time, as noted in the twenty narrative functions elucidated earlier, the Persian Jane acquires characteristics of the archetypal Persian beloved that are missing from the original, which renders her more as a lover, who packages her love within the Victorian social structures and behavioural norms that are most likely to ensure its success.

While Persian does not make as precise distinctions in the language of feeling, it does have the grammatical ability to distinguish levels of intimacy. Jane Eyre’s Persian translations reveal many different levels of intimacy and power relations that are established by the second-person singular form of address. As in French, the singular ‘you’ takes two forms in the Persian language, tow (for simple informal address) and shomā (for formal and plural address). In contrast with the neutral ‘you’ in English dialogues, the Persian translator is able, or even obliged, to impose an intimacy which is non-existent in the English text. In this way, all direct addresses in Jane Eyre are naturally divided into formal and informal forms according to the translator’s interpretation of the relationship between the interlocutors. This means that the translator of Jane Eyre into Persian has tools lacking in the original text to lengthen and shorten the distance between Jane and other characters in the novel in her romantic, domestic, social, and employment relations. For example, in the scene where Jane encounters her bullying cousin, John, we read:

“What do you want?” I asked, with awkward diffidence.

“Say, ‘What do you want, Master Reed?’ was the answer. ‘I want you to come here.’”66

Bahrami Horran translates these ‘you’s differently.67 While John addresses Jane with tow, implying his belief in his natural superiority over her as in a master-servant relation, Jane addresses him with formal forms and shomā, revealing her intention to maintain a distance between them. However, a few lines later, when Jane bursts into rebellious anger, her address changes to tow, breaking the normal superior-inferior relation between them: ‘Wicked and cruel boy!’ I said. ‘You are like a murderer — you are like a slave-driver — you are like the Roman emperors!’68 Different Iranian translators respond to the challenge of rendering address differently. Jane’s addresses to John are rendered in the informal mode throughout Reza’i’s translation, reflecting an approach to Jane’s character which is uncompromising from the beginning.69

Further developing these nuanced uses of tow and shomā, Jane’s relation to her two lovers, Rochester and St John, are represented differently by different translators. In Bahrami Horran’s translation, the first encounter between Rochester and Jane is recounted in a mutual formal manner with both Rochester and Jane addressing each other with shomā.70 However, while Rochester’s address to Jane changes to tow when Jane saves him in the fire and in his proposal to Jane afterwards, Jane’s address to Rochester remains formal until the end even when they are married. The Iranian reader would interpret this as either a sign of Jane’s will to keep her distance, thus actively taking control of the formality involved in her relation to Rochester, or conversely as her passive submission to the master-servant relationship with Rochester even after their intimacy is secured by marriage. These considerations are non-existent in the original Jane Eyre and result from filtering the text through the prism of the Persian language, and its meticulous distribution of formal and informal registers.

The relation of Jane with St John is different in regard to forms of address. The first encounters between the two are managed by shomā until the scene in which St John informs Jane of her inherited wealth, addressing her with tow:71

“And you,” I interrupted, “cannot at all imagine the craving I have for fraternal and sisterly love. I never had a home, I never had brothers or sisters; I must and will have them now: you are not reluctant to admit me and own me, are you?”

“Jane, I will be your brother — my sisters will be your sisters — without stipulating for this the sacrifice of your just rights.”72

The translation of St John’s ‘you’ into tow here shows a desire to get closer to Jane after she demands ‘fraternal and sisterly love’ from him. Meanwhile Jane, using shomā throughout, is resolved to keep her distance except for a transitory moment near the end of their dialogue, when the Persian Jane yields to the intimate mode and addresses St John with tow: ‘And I do not want a stranger — unsympathising, alien, different from me; I want my kindred: those with whom I have full fellow-feeling. Say again you will be my brother: when you uttered the words I was satisfied, happy; repeat them if you can, repeat them sincerely.’73 In Reza’i’s text, this distribution of formality and informality appears somewhat different from Bahrami Horran’s. Except for rare moments, St John does not speak to Jane in formal address, while Jane keeps the formality in her relation to St John until the end.

This differentiated intimacy is also revealing with respect to another range of direct addresses in Jane Eyre, that is, when the autobiographical narrator directly addresses the reader. Different levels of intimacy between the narrator and the reader are built into Reza’i’s and Bahrami Horran’s translations. For example, at the end of Chapter 27:

Gentle reader, may you never feel what I then felt! May your eyes never shed such stormy, scalding, heart-wrung tears as poured from mine. May you never appeal to Heaven in prayers so hopeless and so agonised as in that hour left my lips; for never may you, like me, dread to be the instrument of evil to what you wholly love.74

While Reza’i uses the formal address for the reader, Bahrami Horran uses the informal form.75

The Education of the Persian Jane

Antoine Berman’s ‘retranslation hypothesis’ posits that translations of a work increase in accuracy with respect to the original the more mediated they are across generations.76 Our survey of the translations of Jane Eyre into Persian over seven decades has confirmed Berman’s hypothesis. From Barzin’s first abridged translation in 1950, to one Reza’i’s more recent 2010 translation, heavily annotated with 116 endnotes explaining the allusive intertexts of the novel to the Persian reader, the Persian Jane develops from being an innocent woman from a lower social class in love with an aristocratic married man into an educated, assertive, and confident young woman who gains in autonomy and integrity as she matures, and who learns to overcome oppressive social and gender hierarchies through her innate intellectual and empathetic capacities.

Most early Persian translations of Jane Eyre remove the many allusions in the novel to the Bible, Graeco-Roman mythology, and to writers such as Virgil, Shakespeare, and Walter Scott. This allusive texture is fundamental to the English novel.77 Reza’i clarifies the novel’s allusions in its 116 endnotes, thus attempting to bring the intellectual capacities of the protagonist to light, and making the novel’s status as a Bildungsroman palpable for the Persian reader. Table 2 shows different translators’ renderings of several literary and historical allusions in Jane Eyre:

|

Original reference in Jane Eyre |

Bahrami (1991) |

|||

|

* |

TA |

× |

TR |

|

|

Pamela and Henry, Earl of Moreland (Ch. 1, p. 7) |

* |

T |

T |

R |

|

Goldsmith’s History of Rome (Ch. 1, p. 8) |

* |

T |

× |

R |

|

Gulliver’s Travels (Ch. 3, p. 17) |

* |

T |

× |

R |

|

Guy Fawkes (Ch. 3, p. 21) |

* |

E |

× |

R |

|

Ezekiel: ‘to take away your heart of stone and give you a heart of flesh’ (Ch. 4, p. 27 |

* |

T |

× |

R |

|

Matthew: ‘Love your enemies; bless the that curse you’ (Ch. 6, p. 49) |

* |

T |

× |

R |

|

Key |

|

|

TA |

translates title and author name |

|

T |

translates title only |

|

× |

removes reference |

|

* |

annotates |

|

E |

uses endnote |

|

R |

removes reflection evoked by the reference |

Table 2: Rendering literary and historical allusions in Persian translations of Jane Eyre

When allusions are removed or left untranslated, a considerable part of Jane’s intellectual capacity disappears from view. Even when such details are annotated in Persian translations, they are only restored in the paratextual apparatus. They remain external to the normal processes of reading and severed from the unified texture into which they were originally woven. Both in the case of removal and of annotation, they are moved out of the text, to become ‘hors-texte’, in Derrida’s terms.78 At the beginning of Chapter 2, Jane is locked (domesticated) in the red-room. Here Jane’s knowledge of the French language is disclosed to the reader. Her translational powers become evident while she plays on the French phrase ‘hors de moi’, in the sense of being ‘beside myself’, which is literally translated by the narrator as ‘out of myself’:

I resisted all the way: a new thing for me, and a circumstance which greatly strengthened the bad opinion Bessie and Miss Abbot were disposed to entertain of me. The fact is, I was a trifle beside myself; or rather out of myself, as the French would say: I was conscious that a moment’s mutiny had already rendered me liable to strange penalties, and like any other rebel slave, I felt resolved, in my desperation, to go all lengths.79

Barzin completely removes this reference to Jane’s knowledge of the French language, and employs the Persian term ‘az khod bikhod shoda’ to refer to both ‘beside myself’ and ‘out of myself’.80 Az khod bikhod shodan means ‘to lose one’s self’, more literally ‘to become self-less’, which denotes ‘losing control’. Reza’i picks up on this meaning but loses the word play completely by translating it as ‘I had lost my control’ which makes no sense in conjunction with ‘as the French would say.’81 Bahrami Hurran uses two Persian terms: ‘az khod bikhod shodan’ and ‘be qowl-e farānsavi-hā digar khodam nabudam [as French would say “I was not myself”]’.82 ‘Not myself’ translates ‘out of myself’ and best epitomises Jane’s intellectual and emotional dignity, as manifested in her capacity to get out of herself and to create an autobiographical ‘I’ that is obliged to see one’s self as an other. In Persian literature, ‘love’ is constituted by estrangement or alienation. ‘I was not myself’ is a fundamental element of the Persian lover’s discourse, and informs the lover’s ability to transcend his or her self for the sake of the other.

By viewing literary texts from outside the system in which they were originally produced, translators, comparatists, and scholars of translation can expand the potentialities of the original text. They can confer on it a continued life (Benjamin’s Fortleben), ensuring its survival, its Überleben, across space and time. In the case we have examined, of the Iranian Jane Eyre, as translation was professionalised, translations became more accurate and adept at capturing the nuances of the original. Clearly, the increase in accuracy was a gain. And yet something of the simplicity of Barzin’s inaugural translation may be said to be missing from more recent translations.

Rather than suggesting that one translation methodology is better or more necessary than another, the prismatic approach enables us to insist on the need for both. With inaccurate translations, Iranian readers ran the risk of sentimentalising Jane Eyre. Equally, without compelling translations shaped to the contours of the target culture, and specifically to its engagement with the Persian romance tradition, the translation may never have been read at all. The later accurate versions enable Iranian readers to re-read the novel, without displacing the value of the earlier inaccurate versions. New reception paradigms determine new modes of being for works of world literature. The prismatic approach to translation, with its emphasis on the potentiality of literary texts to determine and transform the conditions of their reception, shows how translators give new life to old originals in the act of translation, sometimes changing their original meanings in radical ways. By using prismatic translation to engage with readers’ horizons of expectation, we can learn, gradually and imperfectly, to read as we might wish to live: according to the Persian principle of unconditional love for the other.

Works Cited

Translations of Jane Eyre

Brontë, Charlotte, Jeyn 'Eyr, trans. by Mahdi Afshar (Tehran: Zarrin, 1982).

—— Jeyn 'Eyr, trans. by Mohammad-Taqi Bahrami Horran (Tehran: Jami, 1996 [1991]).

—— Jen 'Er, trans. by Masʿud Barzin (Tehran: Kanun-e Maʿrefat, 1950).

—— Jeyn 'Eyr, trans. by Nushin Ebrahimi (Tehran: Ofoq, 2009).

—— Jeyn 'Eyr, trans. by Nushin Ebrahimi (Tehran: Ofoq, 2015).

—— Jeyn 'Eyr, trans. by Fereidun Kar (Tehran: Javidan, 1990).

—— Jeyn 'Eyr, trans. by Marzieh Khosravi (Tehran: Ruzgar, 2013).

—— Jeyn 'Eyr, trans. by Maryam Moayyedi (Tehran: Amir Kabir, 2004).

—— Jeyn 'Eyr, trans. by Parviz Najmoddini (Tehran: Towsan, 1983).

—— Jeyn 'Eyr, trans. by Maryam Rasuli (Tehran: Ordibehesht, 2011).

—— Jeyn 'Eyr, trans. by Reza Reza’i (Tehran: Nashr-e Ney, 2010).

Other Sources

ʿAbedini, Hasan, Sad sāl dāstān-nevisi-ye Irān [One hundred years of fiction writing in Iran], 3 vols (Tehran: Cheshmeh, 2001).

Badpa, Moʿin, ‘Dah nokta darbāra-ye romān-e Jeyn Eyr va nevisandash’ [Ten remarks about the novel Jane Eyre and its author], https://www.ettelaat.com/?p=370368

Baraheni, Reza, Kimiyā va khāk [Elixir and Dust] (Tehran: Morgh-e Amin, 1985).

Walter Benjamin, ‘Die Aufgabe des Übersetzers’, Gesammelte Schriften, 7 vols (Frankfurt a.M.: Suhrkamp, 1972), IV/i.

Berman, Antoine, ‘La retraduction comme espace de traduction’, Palimpsestes, 13 (1990), 1–7.

——, The Age of Translation: A Commentary on Walter Benjamin’s ‘The Task of the Translator, trans. by Chantal Wright (London: Routledge, 2018).

Brennan, Zoë, Brontë’s Jane Eyre: A Reader’s Guide (London and New York: Continuum, 2010).

Bürgel, J. C., ‘The Romance’, in Persian Literature, ed. by Ehsan Yarshater (New York: Bibliotheca Persica, 1988), pp. 161–78.

Brontë, Charlotte, Jane Eyre: An Autobiography, ed. by Richard J. Dunn, 3rd edn (New York: W. W. Norton, 2001).

Calsamiglia, Helena, and Teun A. Van Dijk, ‘Popularization discourse and knowledge about genome’, Discourse & Society, 15 (2004), 369–89.

Dehkhoda, Ali Akbar, Loghatnāma, ed. by Mohammad Moin and Sayyed Jafar Shahidi (Tehran: Entesharat va chap-i daneshgah-i Tehran, 1998), II.

Dehqani, Marjan, and Ahmad Saddiqi, ‘Translating Connotations in Novels from English into Persian: Case Study of Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre’, Motāleʿāt-e tarjoma, 36 (2012), 129–43.

Derrida, Jacques, Of Grammatology, trans. by Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak (Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2013 [1997]).

Fish, Stanley, Is There a Text in This Class?: The Authority of Interpretive Communities (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1980).

Ghazzali, Ahmad, Majmuʿa āsār-e Fārsi-ye Ahmad Ghazzāli, ed. by Ahmad Mojahed (Tehran: Entesharat-e Daneshgah-I Tehran: 1979).

Gould, Rebecca Ruth, ‘Sweetening the Heavy Georgian Tongue: Jāmī in the Georgian-Persianate World’, in Jāmī in Regional Contexts: The Reception of ʿAbd al-Raḥmān Jāmī’s Works in the Islamicate World, ca. 9th/15th-14th/20th Century, ed. by Thibaut d’Hubertand Alexandre Papas (Leiden: Brill, 2018), pp. 802–32.

Jauss, Hans Robert, ‘Literary History as a Challenge to Literary Theory’, New Literary History, 2 (1970), 7–37.

Pyrhönen, Heta, Bluebird Gothic: Jane Eyre and its Progeny (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2010).

Propp, V. Ia., Morphology of the Folktale, trans. by Louis A. Wagner, 2nd edn (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1968 [1928]).

Reynolds, Matthew, ‘Passion’, Prismatic Jane Eyre, https://prismaticjaneeyre.org/passion/

Rule, Philip C., ‘The Function of Allusion in Jane Eyre’, Modern Language Studies, 15 (1985), 165–71.

Sattari, Jalal Sāya-ye, Izot va shikar-khand-e Shirin [Iseult’s shadow and Shirin’s sweet smile] (Tehran: Markaz, 2004).

Shamisa, Sirus, Anvāʿ-e adabi [Literary types] (Tehran: Ferdows, 1999).

Takallu, Masumeh, and Behzad Barekat, ‘A Study of Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre through the Prism of New Historicism’, Naqd-e zabān va adabiyāt-e khāreji, 79 (2019), 79–102.

Va‘ezzadeh, Abbas, ‘Rada-bandi-ye dāstān-hā-ye ʿāsheqāna-ye fārsi [‘Typology of Persian romance narratives’]’, Naqd-e adabi, 33 (2016), 157–89.

Zonana, Joyce, ‘The Sultan and the Slave: Feminist Orientalism and the Structure of Jane Eyre’, Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society, 18 (1993), 592–617.

Zolfaqari, Hasan, Yeksad manzuma-ye ʿāsheqāna-ye fārsi [One hundred Persian romance verses] (Tehran: Charkh, 2013).

——, ‘Sākhtār-e dāstāni-ye manzuma-hā-ye ʿāsheqāna-ye fārsi [‘The narrative structure of Persian romance narratives’]’, Dorr-e dari (adabiyāt-e ghenāyi ʿerfāni), 17 (2016), 73–79.

1 All translations from Persian, French, and German are our own. In addition to being supported by the Prismatic Translation project, this work has been facilitated by the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Programme under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie Grant Agreement No. 842125 and under ERC-2017-STG Grant Agreement No 759346.

2 JE, Ch. 24

3 Walter Benjamin, ‘Die Aufgabe des Übersetzers’, Gesammelte Schriften, 7 vols (Frankfurt a.M.: Suhrkamp, 1972), IV/i, p. 11. Our rendering of Überleben as ‘survival’ follows Chantal Wright, who explains in her introduction to Antoine Berman’s The Age of Translation: A Commentary on Walter Benjamin’s ‘The Task of the Translator’ (London: Routledge, 2018), p. 75, why it is problematic to render this term as ‘afterlife’.

4 ‘Strand 6: Prismatic Translation’, Creative Multilingualism, https://www.creativeml.ox.ac.uk/research/prismatic-translation

5 See Zoë Brennan, Brontë’s Jane Eyre: A Reader’s Guide (London and New York: Continuum, 2010), pp. 24–30.

6 Nushin Ebrahimi discusses Iranian feminism in her preface to her translation of Jane Eyre, in Charlotte Brontë, Jeyn 'Eyr, trans. by Nushin Ebrahimi (Tehran: Ofoq, 2015), pp. 7–14. Hereafter Ebrahimi (2015).

7 Hans Robert Jauss, ‘Literary History as a Challenge to Literary Theory’, New Literary History, 2 (1970), 7–37.

8 Stanley Fish, Is There a Text in This Class?: The Authority of Interpretive Communities (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1980).

9 Ma‘sumeh Takallu and Behzad Barekat, ‘A Study of Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre through the Prism of New Historicism’, Naqd-e zabān va adabiyāt-e khāreji, 79 (2019), 79–102; Marjan Dehqani and Ahmad Seddiqi, ‘Translating Connotations in Novels from English into Persian: Case Study of Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre’, Motāleʿāt-e tarjoma, 36 (2012), 129–43.

10 Joyce Zonana, ‘The Sultan and the Slave: Feminist Orientalism and the Structure of Jane Eyre’, Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society, 18 (1993), 592–617, http://tarjomaan.com/article/5949/404.html

11 See Moʿin Badpa, ‘Dah nokta darbāra-ye romān-e Jeyn Eyr va nevisandash [‘Ten remarks about the novel Jane Eyre and its author’]’, https://www.ettelaat.com/?p=370368

16 For example, dubbed and subtitled versions of Jane Eyre’s 2011 and 1997 film adaptations directed by Cary Fukunaga and Robert Young respectively.

17 The catalog of the National Library of Iran lists 38 translations; however 8 of these were never published.

18 Charlotte Brontë, Jen 'Er, trans. by Masʿud Barzin (Tehran: Kanun-e Maʿrefat, 1950). Hereafter Barzin (1950).

19 Charlotte Brontë, Jeyn 'Eyr, trans. by Fereidun Kar (Tehran: Javidan, 1990). Hereafter Kar (1990).

20 Charlotte Brontë, Jeyn 'Eyr, trans. by Maryam Moayyedi (Tehran: Amir Kabir, 2004). Hereafter Moayyedi (2004).

21 Charlotte Brontë, Jeyn 'Eyr, trans. by Marzieh Khosravi (Tehran: Ruzgar, 2013). Hereafter Khosravi (2013).

22 Charlotte Brontë, Jeyn 'Eyr, trans. by Mohammad-Taqi Bahrami Horran (Tehran: Jami, 1996 [1991]). Hereafter Bahrami Horran (1991).

23 Brontë, Jane Eyre, p. 31. This excerpt is translated in Bahrami Horran (1991), p. 49, as

برای اولین بارمزه انتقام را کمی چشیده بودم. مثل یک نوشیدنی معطر وقتی از گلو پایین میرفت گرم و خوشمزه احساس میشد و به اصطلاح مثل یک شربت اصل بود. مزه دبش و تیز آن به من این احساس را میداد که گفتی مسموم شدهام.

A back translation would be as follows: ‘For the first time, I had tasted vengeance a little. Like an aromatic drink (nushidani), when it went down the throat, it was felt warm and delicious, as it’s called, like a genuine syrup (sharbat). Its excellent and sharp taste was felt as if I were poisoned.’

24 For the controversy around Khosravi (2013), see http://www.ensafnews.com/47978/یک-روایت-کنایه-آمیز،-یک-نقد،-یک-جوابیه/