The General Map https://digitalkoine.github.io/je_prismatic_generalmap/ Created by Giovanni Pietro Vitali; © OpenStreetMap contributors

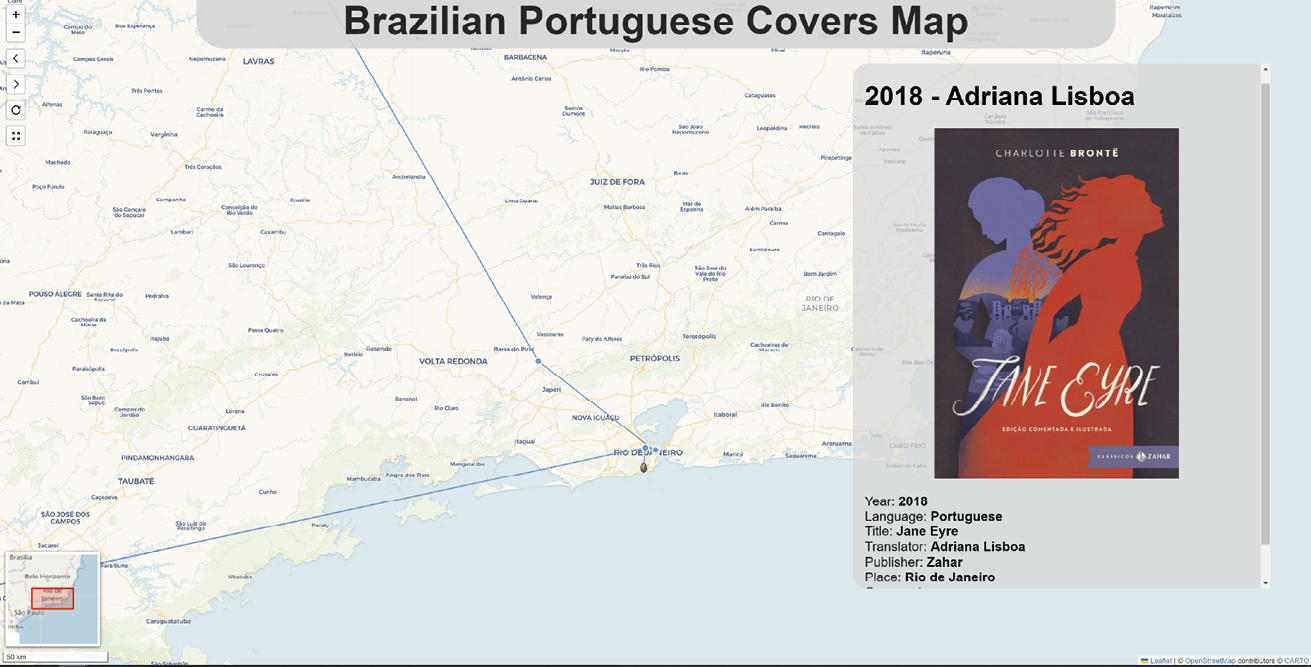

The Brazilian Portuguese Covers Map https://digitalkoine.github.io/brazilian_portuguese_storymap/ Researched by Ana Teresa Marques dos Santos; created by Giovanni Pietro Vitali and Simone Landucci

9. A Mind of her Own: Translating the ‘volcanic vehemence’ of Jane Eyre into Portuguese

© 2023 A. Marques dos Santos & C. Pazos-Alonso, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0319.15

The first image of Jane offered to the reader is that of a young girl trapped indoors. After she picks a book to read, she hides behind the window-seat curtains, paradoxically opting for a form of self-confinement, in order to break mentally free. This incipit hints at the centrality of the prison-escape leitmotif within the novel. In this essay we explore several Portuguese language renditions of Jane Eyre, ranging from the earliest known translation, published in instalments in the nineteenth-century periodical O Zoophilo [Zoophile], through to two twenty-first-century versions, in a selection that spans both Brazil and Portugal. In the process of so doing, we note how, at key moments in the twentieth century, the yearning for freedom that characterizes Brontë’s heroine may acquire further resonances in political contexts informed by dictatorship and censorship (1932–1974 in Portugal and 1964–1985 in Brazil) and, indeed, in their immediate aftermath.

Seven translations were considered: in book-form, three from Brazil and three from Portugal, ranging from 1926 to 2011, with an equal number of male and female translators.1 In addition, we examined the (incomplete) first known translation into European Portuguese, published in O Zoophilo between 1877 and 1882, by an anonymous (but demonstrably female) translator. An eighth version, A Paixão de Jane Eyre, the first European Portuguese translation in book-form (1941), signed by Mécia and João Gaspar Simões, formed part of the project, until it became apparent that the two excerpts chosen were entirely absent from this bowdlerised version.2

The Portuguese language renditions of the imprisonment versus resistance motif in Jane Eyre are explored here through the analysis of two pivotal moments: first, shortly before Jane meets Rochester and, second, as she comes to realize that she cannot possibly marry St John Rivers (Chapters 12 and 34 respectively). Through a close textual analysis of the expressions that surround the prismatic keyword ‘mind’, we discuss not only the explosive captivity-freedom tension, but also, crucially, the decisive expression of Jane’s own subjectivity, tellingly described as ‘volcanic vehemence’ earlier in Chapter 34.3

It is noteworthy that both passages chosen culminate in one long sentence each, thus arguably using style to transmit ‘volcanic vehemence’. As we shall see, in two out of three instances, it is within these meandering sentences that the keyword ‘mind’ appears. Additionally, both passages include references to Jane’s ‘nature’ in close proximity with the semantic field of ‘fire’ (another two prismatic keywords) and, last but not least, her body. This suggests that for Brontë the expression of female subjectivity (the word ‘inward(ly)’ tellingly features in both extracts) is in fact closely linked with both the mind and the body.

Physical and Mental Evasion

The opening of Chapter 12 recounts Jane’s state of mind whenever she ‘took a walk by [herself] in the grounds; […] or when […] [she] climbed the three staircases, raised the trap-door of the attic, and having reached the leads, looked out afar over sequestered field and hill, and along dim sky-line’. Significantly, the reader is reminded that Jane is a woman who resists imprisonment, just before she meets Rochester for the first time.

After stating that in these moments she ‘longed for a power of vision that might overpass that limit’, the narrator addresses her readers directly:

Who blames me? Many, no doubt; and I shall be called discontented. I could not help it: the restlessness was in my nature; it agitated me to pain sometimes. Then my sole relief was to walk along the corridor of the third storey, backwards and forwards, safe in the silence and solitude of the spot, and allow my mind’s eye to dwell on whatever bright visions rose before it — and, certainly, they were many and glowing; to let my heart be heaved by the exultant movement, which, while it swelled it in trouble, expanded it with life; and, best of all, to open my inward ear to a tale that was never ended — a tale my imagination created, and narrated continuously; quickened with all of incident, life, fire, feeling, that I desired and had not in my actual existence.4

Together with ‘to walk’, ‘mind’ indicates the process through which Jane attempts to break free. The narrator blurs the distinction between physical and mental dimensions by placing them on a similar level. ‘To walk’ is implicitly associated with ‘feet’, yet here ‘mind’ is not an abstract entity, but appears linked to the body (‘mind’s eye’) — implying that it is through her mind that Jane obtains ‘that power of vision that might overpass that limit’. Thus, Jane’s interiority is paradoxically signalled through a corporeality that becomes strengthened with two further anatomical references — the heart (an internal organ) and the ear, qualified as an ‘inward ear’. The direction of the movement evoked is not simply, then, from the inside to the outside: in fact, it is external social limitations that lead Jane to her expansive inner world.

The translations by Santarrita and Goettems successfully hint at Jane’s interiority by resorting to similar associations: ‘mind’s eye’ is ‘olhos da mente’ (Goettems) [the mind’s eyes], and ‘visão mental’ (Santarrita) [mental vision]. In contrast to their Brazilian counterparts, the European Portuguese versions unanimously evoke the opposition between material and spiritual world by translating ‘mind’ as ‘espírito’ [spirit]:

|

Brontë |

Zoophilo (1877–82) |

|||

|

‘allow my mind’s eye to dwell on whatever bright visions rose before it’ |

‘dar redea ás fulgurantes visões do meu espirito’5 (give free rein to my spirit’s dazzling visions) |

‘deixava o meu espírito abandonar-se às visões brilhantes luminosas’6 (let my spirit abandon itself to the brilliant visions full of light) |

‘deixar a imaginação expandir-se; quantas visões se me ofereciam ao espírito’7 (let my imagination expand; how many visions offered themselves to my spirit) |

‘dar licença aos olhos do meu espírito para se deleitarem com quaisquer visões auspiciosas que se lhe deparassem’8 (allow my spirit’s eyes to take delight in whichever auspicious visions came before them) |

Rocha’s text maintains Brontë’s association of ‘mind’ and ‘body’ because it keeps the reference to ‘olhos’ (‘os olhos do meu espírito’ [the eyes of my spirit]). The other texts, however, resorted to ‘visões’ [visions] in order to avoid the oddness of that pairing in Portuguese, with Nascimento adding a reference to imagination for clarity. Their preference shifts the focus from the observer to the observed, and thus reduces some of Jane’s ‘power of vision’. In Nascimento’s and Ferreira’s cases, this is complemented by the failure to acknowledge Jane’s own agency, as her ‘spirit’ abandons itself to, or is offered, visions.

As for ‘inward ear’, it becomes ‘audição interior’ (Rocha) or ‘ouvido interior’ (Santarrita and Goettems) [inner hearing, or inner ear, respectively] — or, more figuratively still, ‘ouvidos da alma’ [the ears of the soul], the choice of Cabral do Nascimento.

By Chapter 12, thus, and unlike the opening scene of the novel, the escape from the multiple constraints afflicting Jane is carried out through her own body as well as the tale she imagines. The sequence of seven possessives that punctuates the excerpt (‘my nature’, ‘my sole relief’, ‘my mind’s eye’, ‘my heart’, ‘my inward ear’, ‘my imagination’, ‘my actual existence’) corresponds to a robust assertion of both the power of Jane’s self, and her own awareness of that power to circumvent the limits imposed upon her.

Besides being a translator of English, American, and French literature, Cabral do Nascimento (1897–1978) was a poet himself, linked to the early twentieth-century literary Portuguese saudosismo and modernist movement. This may explain why he seems to have stylistic reasons to reject the reiterated use of the possessive adjective ‘my’ (which he only used for the first instance, ‘minha natureza’ [my nature]) — a reluctance also in evidence when it comes to Chapter 34. In fact, despite the important role of the possessive ‘my’ in foregrounding Jane’s selfhood and connecting it with her body, only Zoophilo’s, Santarrita’s, and Goettems’s versions included nearly as many such markers as Brontë had. On the other hand, while Ferreira’s and Rocha’s renditions of Jane’s acknowledgement of an indomitable force within her (‘I could not help it: the restlessness was in my nature’) left the possessive out, through their choice of the idiomatic expression ‘estava-me no sangue’ [it was in my blood] for ‘was in my nature’, they creatively established an opportune link between the idea of inward activity and the bodily references that the next long and meandering sentence will explore.

Brontë also emphasizes interiority and its ability to provide evasion through the use of the alliteration that immediately precedes ‘my mind’s eye’: ‘safe in the silence and solitude of the spot’. The literal Portuguese correspondents ‘silêncio’ [silence] and ‘solidão’ [solitude] conveniently facilitated the maintenance of a similar alliteration in all translations except for Leyguarda Ferreira’s. In some cases, a third sibilant sound was added by either the translation of ‘safe’ or the inclusion of a different term:

|

Brontë |

Zoophilo (1877–82) |

|||

|

‘safe in the silence and solitude of the spot’ |

‘do seu silêncio e solidão’9 [of its silence and solitude] |

‘segura no silêncio e na solidão’10 [safe in the silence and solitude] |

‘na solidão e no silêncio desse lugar’11 |

‘no silêncio e na solidão, e dar licença aos’12 [in the silence and solitude, and give permission to] |

A later alliteration that describes the ‘tale my imagination created’ (‘quickened with all of incident, life, fire, feeling’), however, was ignored by all the translations considered, except that published in O Zoophilo: ‘animada por grande variedade de peripecias, pelo fogo, pelo sentimento’ [animated by a great variety of incident, by fire, by feeling]. Santarrita and Rocha did nonetheless reproduce Brontë’s style by copying her asyndetic construction for that phrase. The 1926 Brazilian translator and Nascimento preferred alternative strategies, namely a metaphor (‘todos os incidentes, a vida e paixão abrasada’ [all incidents, life and a fiery passion]) and an antithesis (‘possuidora do que nunca tivera e sempre desejara’ [in possession of that which I had never had and had always wished for]), respectively.

Santarrita, Rocha, and the two early anonymous translators paid further close attention to Brontë’s stylistic mastery by maintaining the strikingly long sentence at the core of this passage (from ‘[t]hen my sole relief was[…]’ to ‘in my actual existence’). Although very long sentences are frequently found in Portuguese, several translators broke Brontë’s sentence into smaller ones, whereas this quartet did not modify Brontë’s punctuation. The length of the sentence contributes to the overall effect of conveying the complexity of this multi-faceted evasion experience for Jane, in which her entire self is involved and immersed, evoking both her exterior and, especially, her interior dimensions.

Jane’s personal experience leads to the claim that Brontë makes about women in general in the paragraph that follows (‘[w]omen are supposed to be very calm generally: but women feel just as men feel; they need exercise for their faculties, and a field for their efforts, as much as their brothers do’), an often-cited searing critique of society’s limited expectations of women. While the feminist perspective embraced in O Zoophilo by the 1877 translator in their rendition of this famous indictment of double standards falls outside our brief here, it is worth mentioning that this translator’s creative version of the verb ‘to walk’ as ‘evadir-me’ [to evade] spotlights, even more explicitly than the English text does, that Jane’s experience is about escaping. Tellingly, this contrasts with all later translations, which opted for literal synonyms of the English verb ‘to walk’. The choice is not altogether surprising since this anonymous early version of Jane Eyre can be attributed to Francisca Wood (1802–1900), the Editor of the first overtly feminist periodical in Portugal.13 Wood published feminist versions of the Grimm brothers’ short stories in this periodical, A Voz Feminina (The Female Voice).14 Furthermore, her first-hand knowledge of Britain, where she lived at the time of the publication of Jane Eyre, meant she was ideally placed to subsequently translate a novel that would come to occupy a privileged position in the feminist canon. Her invisible authorship of the serialized translation therefore provides a fitting explanation for the underscoring, through lexical choice in the sentence considered above, of the idea of transcending oppressive patriarchal constraints.

Jane’s rebellious struggle and visceral desire for agency are also successfully reinforced in this nineteenth-century version through the translation of ‘a tale my imagination created’ as ‘uma historia filha da minha imaginação’ (a story daughter of my imagination), thereby throwing into relief the materiality of (gendered) creativity. Interestingly, a couple of additions allow the Zoophilo text to hint more explicitly than the English original at the connection between Jane and Bertha Mason. Although the reader is not yet aware of the gothic motif of the double, since at this juncture Bertha is merely a mysterious figure still identified with Grace Poole, the Zoophilo’s translation connects the two characters by expanding ‘the corridor of the third storey’ into ‘aquelle medonho corredor do terceiro andar de que já falei’ [that terrifying corridor on the third storey which I have already mentioned].

Nearly one century later, faith in the eradication of women’s metaphorical imprisonment was heightened after the fall of the forty year-long Portuguese New State regime, when the translation by Nascimento was published at the end of 1975, more than one year after the peaceful revolution that brought back democracy to the country. The newly-gained sense of freedom that pervaded life in Portugal, in addition to the publisher’s commitment to ‘contribute to freedom from fascist obscurantism’, enabled him to be particularly attuned to Jane’s expressions of freedom.15 Having preferred the verb ‘errar’ [to wander] as a translation of ‘to walk’, Nascimento seizes a different opportunity to convey the idea of ‘evasion’, and renders ‘safe’ as ‘livre’ [free]: ‘livre na solidão e no silêncio desse lugar’ [free in the silence and solitude of the spot]. Similarly, the Brazilian translator of 1926 transfers a closely related notion to yet another sentence by adding the term ‘liberdade’ [freedom] to the translation of ‘to let my heart be heaved by the exultant movement’: ‘onde eu tinha liberdade de deixar arfar com pulsações exultantes o coração’ [where I had the freedom to let my heart heave with exultant throbs] (our emphasis). As their lexical choices are contrasted with the ones made by the other translators (e.g., ‘isolava-me’ [isolated myself] and ‘refugiando-me’ [sheltering], Ferreira and Rocha’s versions respectively), Zoophilo, 1926 anon, and Nascimento emerge as taking Brontë’s implied criticism one step further, since their versions enhance Jane’s free-spirited escape.

‘Mind’

‘Mind’ is a word that occurs 136 times in the course of Jane Eyre. As we saw in the first of the two excerpts under analysis, it is a core term that conveys the prison-escape dichotomy while foregrounding the protagonist’s subjectivity. Nowhere is this clearer than in the second extract, from Chapter 34, where the word ‘mind’ is repeated twice in the space of three sentences, precisely as Jane, through internal monologue in this instance, comes to the realization that the prospect of being shackled and stifled by a marriage to her cousin is intolerable:

I looked at his features, beautiful in their harmony, but strangely formidable in their still severity; at his brow, commanding but not open; at his eyes, bright and deep and searching, but never soft; at his tall imposing figure; and fancied myself in idea his wife. Oh! it would never do! As his curate, his comrade, all would be right: I would cross oceans with him in that capacity; toil under Eastern suns, in Asian deserts with him in that office; admire and emulate his courage and devotion and vigour; accommodate quietly to his masterhood; smile undisturbed at his ineradicable ambition; discriminate the Christian from the man: profoundly esteem the one, and freely forgive the other. I should suffer often, no doubt, attached to him only in this capacity: my body would be under rather a stringent yoke, but my heart and mind would be free. I should still have my unblighted self to turn to: my natural unenslaved feelings with which to communicate in moments of loneliness. There would be recesses in my mind which would be only mine, to which he never came, and sentiments growing there fresh and sheltered which his austerity could never blight, nor his measured warrior-march trample down: but as his wife — at his side always, and always restrained, and always checked — forced to keep the fire of my nature continually low, to compel it to burn inwardly and never utter a cry, though the imprisoned flame consumed vital after vital — this would be unendurable.

The keyword ‘mind’ is translated in several different ways, and a distinction can be drawn between the choices in European and in Brazilian Portuguese. For the latter, in both passages, ‘mind’ is generally ‘mente’ or connected to ‘mente’, which in English corresponds to the most intellectual sense of the word, as in ‘mental’ processes. The exception to this, among the Brazilian translations, is the anonymous 1926 version which omits both references to ‘mind’ in Chapter 34 — having also avoided the earlier ‘mind’s eye’, in Chapter 12, through the introduction of the idea of ‘imagination’: ‘vista imaginativa’ [imaginative vision]. The expression ‘my heart and mind would be free’ is conflated with ‘my natural unenslaved feelings’, and results in a combination that spared the translator the trouble of finding a way to convey ‘unenslaved’ in Portuguese: ‘ficando assim livres meu coração e meus sentimentos naturaes’ [my heart and natural feelings would thus be free].

In fact, in this translation the whole excerpt is heavily cut, condensed, and reduced to around six lines of text. The translator removes the references to St John Rivers’s physique and, hence, to his cold harshness, possibly in order to avoid criticism of a clergyman (whilst keeping his positive aspects, ‘his courage and devotion and vigour’ as ‘sua coragem, sua devoção, seu vigor’). The translator summarised the passage, conveying only its gist (Jane looks at St John, states the extent to which she could accompany him, briefly refers to what type of freedom she would retain, and how constrained she would be, and expresses the intensity of her sacrifice through similar fire imagery). The richly vivid details provided by the English text for each one of these ideas are missing. The justification for this, and, moreover, the acknowledgement of the poetic worth of what was left out, can be found in the preface signed by the anonymous translator:

Na segunda metade [do livro] […] tomei a liberdade de cortar desapiedadamente tudo quanto pudesse impedir a carreira dos eventos para o desenlace final. Mais de uma nuance de sentimentos, aliás subtilissima, mais de uma flôr poetica, aliás fragantissima, ficaram esmagadas pela marcha inexoravel que os factos peremptoriamente exigiam.16

[In the second half of the book, I took the liberty to cut ruthlessly everything that could prevent the flow of events towards the final denouement. More than one nuance of feelings, however subtle, more than one poetic flower, however fragrant, was crushed by the relentless march categorically demanded by the facts.]

In the European Portuguese versions of Chapter 34, alternative terms for ‘mind’ appear. A chronological overview of the lexical choices reveals a slow move towards a twenty-first-century interpretation of ‘mind’ that foregrounds Jane’s intellect:

|

Brontë |

|||

|

‘my heart and my mind would be free’ |

‘o meu coração e o meu espírito conservar-se-iam livres’ |

‘o coração e a alma continuariam livres’ |

‘o meu coração e a minha mente seriam livres’ |

|

‘There would be recesses in my mind which would be only mine’ |

‘no meu espírito existiriam recantos que me pertenceriam unicamente’17 |

‘haveria recessos na minha mente que seriam só meus’18 |

‘haveria recessos na minha mente que seriam só meus’19 |

While Ferreira opted for a term connected to spirituality for both instances of ‘mind’, Nascimento chose the association with ‘intellect’ in one instance, and finally Rocha settled for ‘intellect’ in both cases (our emphasis in bold). Looking at the 1975 and 2011 versions, the option of ‘alma’ in the 1975 text arguably suggests a lexical choice still predominantly informed by the religious context promoted by the dictatorship up to 1974, whereas the 2011 translation moves away from ‘espírito’ and ‘alma’ [spirit, and soul] and prefers the more cerebral ‘mente’. Implied here is also a different understanding of what Jane was attempting to express and, consequently, of her subjectivity: her intellectual freedom was important to her and not to be sacrificed in a marriage to St John Rivers. In short, by 2011, Jane’s faculty of reasoning has gained more prominence.

The different weight of ‘mente’, as opposed to ‘espírito’ or ‘alma’, is all the more evident in Nascimento’s text, where having interpreted the second instance of ‘mind’ as ‘mente’, he is led to correct Brontë’s seemingly contradictory subsequent allusion to ‘sentiments’:

Brontë: There would be recesses in my mind which would be only mine, to which he never came, and sentiments growing there fresh and sheltered […]

Nascimento: Haveria recessos na minha mente que seriam só meus, e ideias que ali se desenvolveriam, frescas e abrigadas […]20

[There would be recesses in my mind which would be only mine, and ideas which would develop there, fresh and sheltered]

While Rocha chooses the same word to translate ‘mind’ in both cases, Nascimento’s preference for ‘mente’ instead of ‘alma’ [soul] in the second instance may be explained by the wish to allow the Portuguese Jane to use the alliteration, besides the double possessive, to vigorously reiterate her selfhood, as in English: ‘minha mente … meus’ [my mind … mine].

Master and Slave

In Chapter 12, imprisonment arises from limits imposed mainly by Jane’s physical, social, and gender circumstances. In Chapter 34, however, it becomes directly bound up with systemic constraints generated by unequal male-female relations. A number of devices in Brontë’s text combine to create a feeling of entrapment, ultimately in order to justify Jane’s rejection of the possibility of a marriage that, by the standards of Victorian society, would have been considered advantageous. Several terms used to characterise her putative union to St John conjure up unambiguous images of curtailment of freedom: ‘masterhood’, ‘imprisoned’, ‘yoke’, ‘restrained’, and ‘checked’. This contrasts with Jane’s yearning to remain ‘unenslaved’.

Leyguarda Ferreira’s 1951 version of the excerpt does not shy away from portraying the relationship in terms of male dominance. As shown below, the Portuguese text resorts to the repetition of different forms of the verb ‘to dominate’ (our emphasis in bold):

|

Brontë |

|

|

‘at his tall imposing figure; and fancied myself in idea his wife’ |

‘para o seu vulto imponente que parecia dominar-nos e supus-me sua mulher’ |

|

‘but as his wife — at his side always, and always restrained, and always checked — forced to keep the fire of my nature continually low’ |

‘Mas como sua mulher — constantemente dominada, obrigada a dominar-me’21 |

On the one hand, the notion of ‘dominance’ is foregrounded, but on the other hand, following the reference to physical dominance, the second allusion, ‘constantemente dominada’, is ambiguously vague in comparison to the original poly-syndetic tricolon describing the marital relationship (i.e., ‘at his side always, and always restrained, and always checked’). The same could be said of ‘obrigada a dominar-me’ [forced to control myself] as a laconic translation of ‘forced to keep the fire of my nature continually low’. The possible sexual connotation does not seem to explain the smoothing over of Brontë’s metaphor, considering that the translation keeps the fire imagery of the next sentence (‘forced […] to compel it to burn inwardly and never utter a cry’) graphically conveying it as ‘obrigada […] a consumir-me nas próprias chamas sem soltar um grito’ [forced to consume myself in my own flames without uttering a cry]. Rather, Ferreira’s habitual shortening practice, which has been criticized as resulting in ‘free adaptations’ rather than complete translations, seems to be a more plausible reason.22

Even when imagining herself working alongside St John as his comrade rather than his wife, the everyday subjugation that Jane would be forced into, as a result of her gender, is highlighted: she would be ‘controlled’ by him (‘constantemente dominada’) as well as by herself (‘obrigada a dominar-me’). While the reference to self-control expands the scope in order to signal that systemic expectations of feminine modesty entail self-disciplining, Ferreira strengthens the idea of female pliability to male dominance through additional lexical choices:

|

Brontë |

|

|

‘[…] I would […] accommodate quietly to his masterhood’ |

‘[…] estava disposta […] a sujeitar-me à sua autoridade’23 (I was willing to subject myself to his authority) |

Through the rendition of ‘to accommodate quietly’ as ‘sujeitar-me’ [to subject myself] and ‘masterhood’ as ‘autoridade’ [authority], Ferreira reinforces the image of female subjection to unequivocal male domination. Such rendition chimed with the prevailing Portuguese conservative patriarchal ideology of the 1950s, according to which men were indeed the figures of authority (and explicitly so within marriage: for example ‘the 1933 Constitution stated that the husband was head of the family and that it was he who wielded authority’).24 On the other hand, by highlighting Jane’s forced subordination, Brontë’s phrasing may strike the modern reader as subtly bolstering her character’s justification for ultimately rejecting St John Rivers’ supremacy.

A chronological perspective of the translational choices for ‘masterhood’ in the corpus can again be useful in highlighting shifting interpretations of the relationship between Jane and her suitor. As the choices become less charged, they hint at the way the distribution of power in the male/female relationship becomes increasingly perceived as more balanced over time:

|

Brontë |

|||

|

‘masterhood’ |

‘autoridade’25 [‘authority’, with connotations of power and control, entailing subjection] |

‘primado’26 [‘primacy’, implying a hierarchy of sorts, but with a subtler connection with the idea of power] |

‘orientação’27 [‘directions, guidance’, with connotations of help, and no explicit mention of power dynamics] |

Likewise, in the Brazilian versions, the 2010 option for ‘direção’ [guidance] is very similar to the choice of ‘orientação’ by the Portuguese Rocha in 2011, whereas the 1983 translation by Santarrita still preferred ‘domínio’ [dominance].

Jane’s consideration of the dire consequences of her imprisonment through marriage is also aptly captured by the use of adjectives with prefixes of negation. These represented an interesting challenge for the translators, though in most cases they were able to use similarly prefixed adjectives available in Portuguese, and thus keep the negativity underlying the English expression: for instance, the final ‘unendurable’ was translated within the range of the ideas of ‘intolerable’ or ‘unbearable’, as ‘intolerável’ (Nascimento and anon. 1926) and ‘insuportável’ (Rocha and Santarrita), with Goettems instead choosing ‘inaceitável’ [unacceptable], perhaps doubly referring to the marriage offer itself.

In this excerpt, one sentence stands out not only because it contains two adjectives prefixed by ‘un’, but also because it is located between the two sentences featuring the word ‘mind’: ‘I should still have my unblighted self to turn to: my natural unenslaved feelings with which to communicate in moments of loneliness’. Both ‘unblighted’ and ‘unenslaved’ have a positive resonance. For ‘unenslaved feelings’ Santarrita and Rocha kept the suggestion of a master-slave relationship, using the expression ‘sentimentos não escravizados’ [non enslaved], whereas others lost that allusion by preferring the positive but more abstract ‘freed’ (‘sentimentos libertos’, Nascimento). Goettems’s translation, ‘pensamentos livres’ [free thoughts], accentuates the cerebral by commuting ‘feelings’ into ‘thoughts’.

Moreover, this sentence is pivotal in communicating Jane’s inner resistance and self-preservation, since it is one of the only two times in the course of the entire novel where the expression ‘my […] self’ features. Conveying ‘my unblighted self’ as ‘o meu eu intato’ [my intact self] (Santarrita) or ‘a minha identidade intacta’ [my intact identity] (Rocha) is matched by a choice for ‘unenslaved’ which necessarily implies a skewed relationship with someone else: ‘não escravizados’ [non-enslaved] (Santarrita and Rocha). By contrast, a less personalized rendition of ‘my unblighted self’ as ‘o meu mundo indestrutível’ [my indestructible world] corresponds to a more abstract paraphrase of the adjective ‘unenslaved’ as ‘livres’ [free] (Goettems).

Striving for Selfhood: The Possessives ‘my’ Versus ‘his’

One of the most effective devices employed by Brontë to underscore Jane’s subjectivity is the repeated use of the possessive ‘my’. Significantly, in this passage, it only makes an appearance in the second part of the paragraph, when the focus shifts to the mainly inner consequences that her marriage, considered in the first, would have upon her. She is at pains to describe not merely the suffering arising from the envisaged curtailment of freedom, but, crucially, its pervasive extent. She does so with such efficiency that, in the words of Jean Wyatt, ‘[n]ot even Virginia Woolf’s Mrs Dalloway could conjure up a more frightening vision of patriarchal domination invading every room of the soul’.28

No doubt for stylistic reasons, both Nascimento and Santarrita, both male, preferred to ignore the mark of possession on two occasions, and have ‘my body’ simply as ‘o corpo’ [the body] and ‘my heart and mind’ as ‘o coração e a alma’ (Nascimento) and ‘o coração e a mente’ (Santarrita) [the body and the soul, and the body and the mind, respectively]. This is entirely permissible in Portuguese, and indeed a stylistically superior choice under most circumstances. As we have seen, the 1926 Brazilian translation and Leyguarda Ferreira’s version were abridged, which accounts for a lower number of occurrences of ‘my’ in those texts.

The 2010 and 2011 translations, on the other hand, have each added two more possessive forms to the seven that can be found in the English source text:

|

Brontë |

||

|

‘Meu corpo’ |

‘o meu corpo’ |

|

|

‘my heart and mind’ |

‘meu coração e minha mente’ |

‘o meu coração e minha mente’ |

|

‘my unblighted self |

‘o meu mundo’ |

‘a minha identidade’ |

|

‘my natural unenslaved feelings’ |

‘meus pensamentos…’ |

‘os meus sentimentos…’ |

|

‘my mind’ |

‘na minha mente’ |

‘na minha mente’ |

|

‘only mine’ |

‘só meus’ |

‘só meus’ |

|

‘the fire of my nature’ |

‘da minha natureza’ |

‘da minha natureza’ |

|

‘consumed vital after vital’ |

‘consumisse minhas entranhas’29 |

|

|

‘burn inwardly’ |

‘arder no meu íntimo’30 |

Even though it could be argued that in this instance the later translations once again emerge as being more receptive to the reinforcement of female subjectivity, the added possessives are intimately bound to the translational options in lexical terms: ‘coração’ (heart) and ‘mente’ (mind) are masculine and feminine nouns respectively and, although not compulsory, each can be preceded by its respective gendered possessive adjective. It is therefore impossible to pinpoint whether the use of the possessive was the consequence or the cause of the lexical choice. Choosing to translate ‘vital after vital’ as ‘entranhas’ [entrails] may also lead to the addition of the possessive (although Santarrita managed to use ‘entranha(s)’ without a possessive), as does conveying ‘inwardly’ as ‘no meu íntimo’ [in my inner core].

Consistency in terms of attention devoted to Brontë’s use of the possessive can, nonetheless, help to support the claim that more recent translators were particularly mindful of the effect this marker has. Goettems’s version paid a similar degree of attention to Brontë’s use of ‘my’ in the Chapter 12 passage (where it occurs seven times in English and six times in Portuguese), and here to the prevalence of the contrasting ‘his’. The latter is initially present in Jane’s physical description of St John through a series of parallel constructions that include both favourable and critical comments. Whereas other translations seem to ignore or downplay the repeated occurrences of this marker, Goettems’s text offers a solution which helps to avoid the redundant tone that the repetition of ‘his’ at the beginning of the passage could easily entail in Portuguese — it uses Brontë’s pauses to break the sentence into smaller units (our emphasis in bold):

I looked at his features, beautiful in their harmony, but strangely formidable in their still severity; at his brow, commanding but not open; at his eyes, bright and deep and searching, but never soft; at his tall imposing figure; and fancied myself in idea his wife.

Olhei para os seus traços, belos em sua harmonia, mas estranhamente temíveis na sua severidade. Para sua fronte autoritária, mas não aberta. Para os seus olhos, brilhantes e profundos e inquisidores, mas ainda assim nunca ternos. Para sua figura alta e imponente; e me imaginei como sua esposa…31

Breaking up this description into a series of short nominal sentences creates a lingering, slow motion effect. It arguably lengthens perception (both Jane’s and the reader’s) underscoring a self-conscious thought-process. Moreover, Goettems’s translation of her suitor’s ‘strangely formidable’ features as ‘estranhamente temíveis’ [strangely fearsome] emphasises Jane’s own awareness (and concomitant rejection) of gender-based domination, also present both in Rocha’s identical rendering of this phrase and in Nascimento’s choice of a similar qualifier (‘estranhamente assustadoras’ [strangely frightening]).

Last but not least, there is a compelling argument in favour of the hypothesis that recent translations seek to self-consciously spotlight Jane’s assertive subjectivity: both Goettems and Rocha, unlike their predecessors, opt to convey the start of the sentence ‘I should still have my unblighted self to turn to’ as ‘Eu ainda teria’ [I would still have] and ‘Eu continuaria a ter’ [I would keep on having] respectively. Bearing in mind that in Portuguese the use of the first-person pronoun is unnecessary here and therefore redundant, its presence speaks volumes.

Conclusion

In Chapter 35, when Jane declines to become his wife, St John remonstrates with her as follows: ‘Your words are such as ought not to be used: violent, unfeminine, and untrue. They betray an unfortunate state of mind’. This is the only time that Jane is explicitly qualified as ‘unfeminine’ in the course of the novel. According to prevailing social codes of mid-nineteenth-century England which undoubtedly extended well into the long twentieth century, her rebellious state of mind may indeed be labelled ‘unfeminine’ and even ‘violent’, but surely the real purpose of Jane Eyre is to challenge these codes and stifling expectations: in the first passage Jane escapes by bursting from the straitjacket of convention through the power of her imagination; in the second, even more radically, she does so by asserting vehemently to herself and the reader her right to an authentic self, outside marriage. Yet ‘volcanic vehemence’, situated as she put it between ‘absolute submission’ and ‘determined revolt’, does not belong exclusively to Jane: ultimately it is a rhetorical means for Brontë to explore the prison-escape leitmotif that underpins the novel. Through the volcanic self-expression of her fictional character, then, Brontë exposes gender politics by insistently interrogating the right to refuse limitative patriarchal expectations of women.

The communicative immediacy of a transgressive first-person voice hinges on Brontë’s subtle deployment of a host of stylistic features including, as was observed here, sentence length, alliteration, adjectives with negating prefixes as well as a proliferation of possessives. These present multiple challenges for translators. To what extent did successive translations into Portuguese over the last century-and-a-half manage to communicate the fire and restlessness that inhabit the mind of both the author and her creation, in order to transmit Jane’s visceral need to be true to her ‘self’?

As might be expected, the last four versions considered here, published from 1975 onwards, reveal a growing willingness on the part of translators to showcase Jane’s spirited ‘nature’ and intellect. It seems that the two twenty-first-century female translators were, on the whole, more closely attuned to the textual devices in the English original that articulated subjectivity and, as such, they accentuated it, for instance through the liberal use of possessives. Rocha’s rendition of life-affirming vehemence is especially striking in her version of the first passage, while Goettems’s translation generates an arguably more cerebral Jane, especially in the second passage.

At their best, translators resort to devices such as metaphor and antithesis, in addition or as alternatives to Brontë’s rhetorical strategies. Their creativity enables them to forge opportunities unavailable in the English text to reinforce Brontë’s revolutionary criticism of a woman’s role and place in society. In that light, it is highly significant that the earliest known translation into European Portuguese, the nineteenth-century incomplete rendition published in O Zoophilo, proved to be comfortable with the unfettered expression of subjectivity and inner revolt as a means of female self-actualization. Interestingly, it threw into relief the gendering of creativity by describing the tale that Jane wove inwardly as ‘uma historia filha da minha imaginação’ [a story daughter of my imagination].

While, more broadly speaking, this pioneer version is underscored by the belief in women’s intellectual freedom, conversely some early- and mid-twentieth-century translators reacted to volcanic vehemence with ambivalence or even silence. As we saw, the 1926 Brazilian version suppresses later sections of the text. More significantly, in the 1951 Portuguese version, Ferreira’s condensing practice allows her to elide significant bits and avoid ideological difficulties, as she seems to re-interpret both female yearnings and male-female relationships in line with the conservative gendered logic of the dictatorship. The most extreme case of muteness in a cultural landscape informed by censorship, however, is to be found in the earliest European Portuguese translation in book-form (1941) where Mécia and João Gaspar Simões handled the complexity of the material underpinning the source text through conspicuous avoidance altogether, in other words, through the glaring omission of both passages chosen for analysis here. Perhaps nowhere is the seismic power of Jane’s mind more strikingly evident than when the transmission of core moments, where ‘natural unenslaved feelings’ are vocally articulated, is considered so perilously transgressive that it can only be met with absolute suppression and deafening silence.

Works Cited

Translations of Jane Eyre

Brontë, Charlotte, ‘Joanna Eyre’, O Zoophilo (14 January 1877, p. 4 to 28 September 1882, pp. 1–2).

——, Joanna Eyre (Petropolis: Typographia das ‘Vozes de Petropolis’, 1926).

——, A Paixão de Jane Eyre, trans. by Mécia and João Gaspar Simões (Lisbon: Editorial Inquérito, 1941).

——, O Grande Amor de Jane Eyre, trans. by Leyguarda Ferreira (Lisbon: Edição Romano Torres, 1951).

——, Jane Eyre, trans. by João Cabral do Nascimento (Porto: Editorial Inova, 1975).

——, Jane Eyre, trans. by Marcos Santarrita (Rio de Janeiro: Francisco Alves, 1983).

——, Jane Eyre, trans. by Doris Goettems (São Paulo: Landmark, 2010).

——, Jane Eyre, trans. by Alice Rocha (Barcarena: Editorial Presença, 2011).

Other Sources

1968–1978. Editorial Inova/Porto: Uma Certa Maneira de Dignificar o Livro (n.p.: Inova, 1978).

Cabral, Afonso Reis, ‘Leyguarda Ferreira’, http://romanotorres.fcsh.unl.pt/?page_id=59#F

Cortez, Maria Teresa, Os contos de Grimm em Portugal. A recepção dos Kinder-und Hausmärchen entre 1837 e 1910 (Coimbra: Minerva (Centro Interuniversitário de Estudos Germanísticos) and Universidade de Aveiro, 2001).

Cova, Anne and António Costa Pinto, ‘Women under Salazar’s Dictatorship’, 1.2 (2002), 129–46.

Marques dos Santos, Ana Teresa, ‘La capacidad de visibilidad de la traductora invisible: mujeres y traducción en el caso de la Jane Eyre portuguesa del siglo XIX’, in Traducción literaria y género: estrategias y práticas de visibilización, ed. by Patricia Álvarez Sánchez (Granada: Editorial Comares, 2022), 51–62.

——, ‘A primeira Jane Eyre portuguesa, ou como o Órgão da Sociedade Protetora dos Animais trouxe Charlotte Brontë para Portugal (1877–1882)’, Revista de Estudos Anglo-Portugueses (forthcoming).

Melo, Daniel, História e Património da Edição em Portugal—A Romano Torres (Famalicão: Edições Húmus, 2015).

Pazos-Alonso, Cláudia, Francisca Wood and Nineteenth-Century Periodical Culture: Pressing for Change (Oxford: Legenda, 2020), https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv16kkzkt

Silva, Jorge Bastos da, ‘A Lusitanian Dish: Swift to Portuguese Taste’, in The Reception of Jonathan Swift in Europe, ed. by Hermann J. Real (London: Continuum, 2005), pp. 79–92.

Sousa, Maria Leonor Machado de, ‘Dickens in Portugal’, in The Reception of Charles Dickens in Europe, ed. by Michael Hollington (London: Bloomsbury, 2013), pp. 197–211.

Wyatt, Jean, ‘A Patriarch of One’s Own: Jane Eyre and Romantic Love’, Tulsa Studies in Women’s Literature, 4 (1985), 199–216.

1 Joanna Eyre, unsigned translation, in O Zoophilo [Zoophile] (Lisbon, 1877–82); Joanna Eyre, trans. by anonymous (Petropolis: Typographia das ‘Vozes de Petropolis’, 1926). This is presumably a male translator according to the masculine form ‘o traductor’ used to sign the ‘translator’s preface’; O Grande Amor de Jane Eyre, trans. by Leyguarda Ferreira (Lisbon: Edição Romano Torres, 1951); Jane Eyre, trans. by João Cabral do Nascimento (Porto: Editorial Inova, 1975); Jane Eyre, trans. by Marcos Santarrita (Rio de Janeiro: Francisco Alves, 1983); Jane Eyre, trans. by Doris Goettems (São Paulo: Landmark, 2010); Jane Eyre, trans. by Alice Rocha (Barcarena: Editorial Presença, 2011). The translations will henceforth be referred to as Zoophilo, 1926 anon., Ferreira, Nascimento, Santarrita, Goettems, and Rocha, respectively.

2 A Paixão de Jane Eyre, trans. by Mécia and João Gaspar Simões (Lisbon: Editorial Inquérito, 1941). Cuts are extensive, sometimes corresponding to whole pages.

3 It is not possible to consider the 1877–82 translation of ‘mind’ in Chapter 34 because the last instalment of Joanna Eyre, published in O Zoophilo on 28 September 1882, corresponds to Chapter 27.

4 JE, Ch. 12. See Chapter VI below for further discussion of this passage.

5 Zoophilo, 13 December 1877, p. 2.

6 Ferreira, p. 128.

7 Nascimento, p. 118.

8 Rocha, p. 148.

9 Zoophilo, 13 December 1877, p. 2.

10 1926, p. 172 and Santarrita p. 101.

11 Nascimento, p. 118.

12 Rocha, p. 148.

13 See Cláudia Pazos-Alonso, Francisca Wood and Nineteenth-Century Periodical Culture: Pressing for Change (Oxford: Legenda, 2020), pp. 178–80, and Ana Teresa Marques dos Santos, ‘A primeira Jane Eyre portuguesa, ou como o Órgão da Sociedade Protetora dos Animais trouxe Charlotte Brontë para Portugal (1877–1882)’, Revista de Estudos Anglo-Portugueses (forthcoming) for the multiple contextual and stylistic arguments that support such an attribution.

14 Maria Teresa Cortez, Os Contos de Grimm em Portugal. A recepção dos Kinder- und Hausmärchen entre 1837 e 1910 (Coimbra: Minerva and Universidade de Aveiro, 2001), pp. 89–103.

15 1968–1978. Editorial Inova/Porto: Uma Certa Maneira de Dignificar o Livro (n.p.: Inova, 1978), p. 85.

16 ‘Prefácio do Tradutor’ [Translator’s Preface], 1926 anon, p. 8.

17 Ferreira, p. 371.

18 Nascimento, p. 420.

19 Rocha, p. 533.

20 Nascimento, p. 420.

21 Ferreira, p. 371.

22 See Afonso Reis Cabral, ‘Leyguarda Ferreira’, http://romanotorres.fcsh.unl.pt/?page_id=59#F, and Daniel Melo, História e Património da Edição em Portugal — A Romano Torres (Famalicão: Edições Húmus, 2015), p. 80. Maria Leonor Machado de Sousa considers this ‘<<simplifying>> habit’ a regular practice by the publisher. Maria Leonor Machado de Sousa, ‘Dickens in Portugal’, in The Reception of Charles Dickens in Europe, ed. by Michael Hollington (London: Bloomsbury, 2013), pp. 197–211 (p. 198, p. 206).

23 Ferreira, p. 371.

24 See Anne Cova and António Costa Pinto, ‘Women under Salazar’s Dictatorship’, Portuguese Journal of Social Science 1(2), (2002), 129–46 (129). An analysis of a different translation by Ferreira reached a similar conclusion regarding another aspect of the dictatorship values: patriotism. See Jorge Bastos da Silva, ‘A Lusitanian Dish: Swift to Portuguese Taste’, in The Reception of Jonathan Swift in Europe, ed. by Hermann J. Real (London: Continuum, 2005), pp. 79–92.

25 Ferreira, p. 371.

26 Nascimento, p. 420.

27 Rocha, p. 533.

28 Jean Wyatt, ‘A Patriarch of One’s Own: Jane Eyre and Romantic Love’, Tulsa Studies in Women’s Literature, 4 (1985), 199–216 (208).

29 Goettems, p. 358.

30 Rocha, p. 533.

31 Goettems, p. 358.