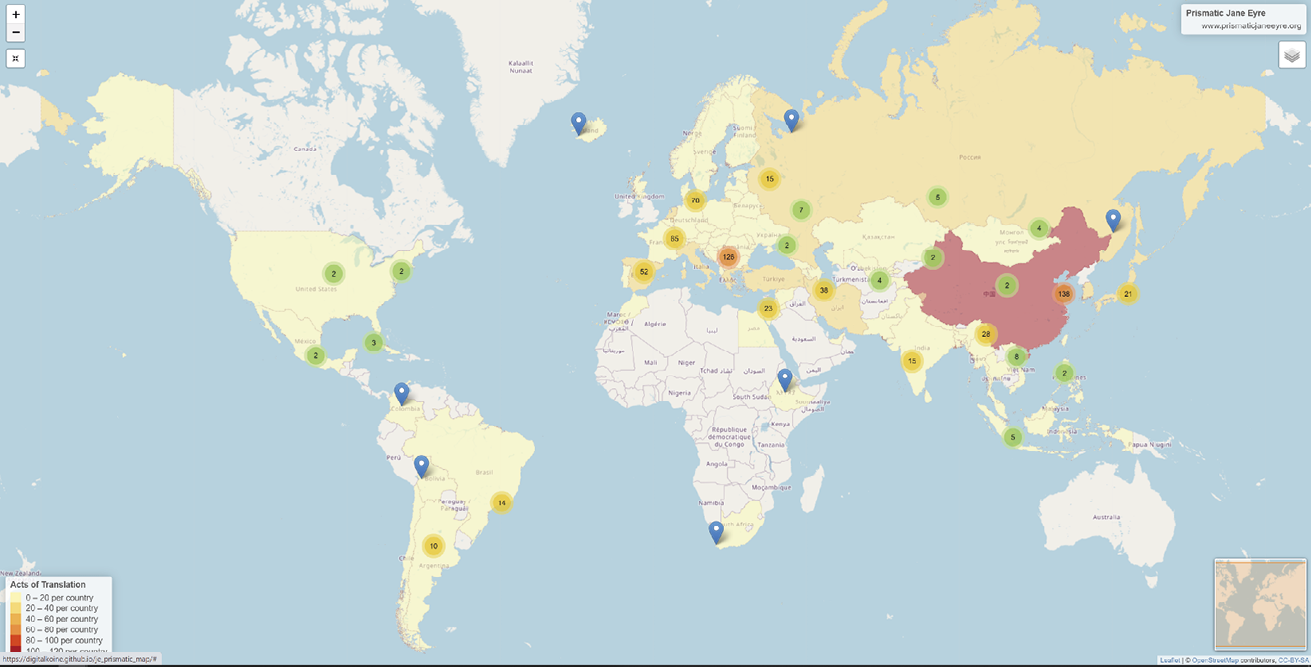

The World Map https://digitalkoine.github.io/je_prismatic_map Created by Giovanni Pietro Vitali; maps © Thunderforest, data © OpenStreetMap contributors

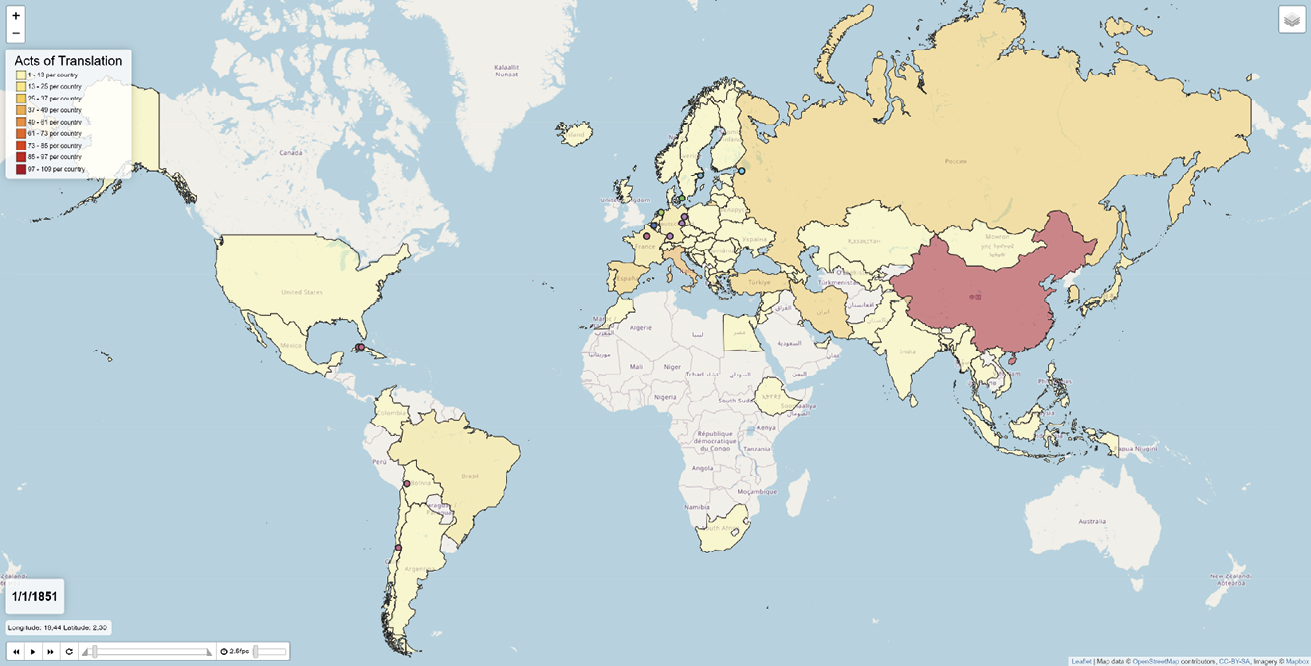

The Time Map https://digitalkoine.github.io/translations_timemap Created by Giovanni Pietro Vitali and Simone Landucci;© OpenStreetMap contributors, © Mapbox

I. Prismatic Translation and Jane Eyre as a World Work

© 2023 Matthew Reynolds, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0319.02

Translations Among Other Texts

The corpus of translations that we have (variably, selectively) explored is vast. Using blunt, quantitative terms which I will qualify in the pages that follow, we can speak of 618 ‘translations’ over 176 ‘years’ into 68 ‘languages’: in short — or rather in long, in very long — a textual multitude of something like 100,000,000 words. Yet this enormous body of material is only a subset of the even larger array of texts — both written and in other media — that have been generated by Jane Eyre in one way or another, including adaptations, responses and critical discussion (this publication takes its place among that multitude). There are at least fifty films going back to the earliest days of cinema, most of them in English but with versions also in Arabic, Czech, Dutch, German, Greek, Hindi, Hungarian, Italian, Kannaḍa, Mandarin, Mexican Spanish, Tamil and Telugu.1 There have been TV series and adaptations for radio, again in many moments, languages and locations.2 A series of powerful lithographs from the novel has been made by the Portuguese artist Paula Rego. Now there are fan fictions, blogs and at least one vlog, and erotic mash-ups which interleave Brontë’s text with throbbing scenes of passion.3 Back in the mid-nineteenth century — indeed, almost as soon as it was published — the novel was being re-made for the stage. The most influential dramatization was Charlotte Birch-Pfeiffer’s Die Waise aus Lowood [The Orphan of Lowood] of 1853: it neutered the scandalous heart of the book by changing Bertha from Mr Rochester’s own wife to that of his dead brother; she also becomes the mother of Adèle. Over the ensuing decades this play was much performed, in German and other languages, across Europe, the UK and the USA, lending its title also to many translations of the novel.4 In India, as Ulrich Timme Kragh and Abhishek Jain show in Essay 1 below, Jane Eyre was freely re-written first in Bengali and then in Kannada, as Sarlā [সরলা] by Nirmmalā Bālā Soma [নির্ম্মালা বালা সোম] and Bēdi Bandavaḷu [ಬೇಡಿ ಬಂದವಳು] by Nīla Dēvi [ನೀಳಾ ದೇವಿ] in 1914 and 1959 respectively, well before it was translated.5 And of course Jane Eyre has had a pervasive, energising influence on English-language literary writing, from Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s Aurora Leigh (1856) to Henry James’s The Turn of the Screw (1898), from Daphne du Maurier’s Rebecca (1938) to Jean Rhys’s Wide Sargasso Sea (1966), together with a scattering of more recent fiction, such as Tsitsi Dangarembga’s Nervous Conditions (1988), Jamaica Kincaid’s Lucy (1990), Ali Smith’s Like (1997), Leila Aboulela’s The Translator (1999) and Aline Brosh McKenna and Ramón K. Pérez’s graphic novel Jane (2018).

Alongside these — and many more — proliferating imaginative responses, the novel has always generated vigorous critical discussion, from excited early reviews, through percipient comments by twentieth-century writers such as Virginia Woolf and Adrienne Rich, to the explosion of academic scholarship and criticism which has, since the 1970s, found in Jane Eyre a focus for Marxist, feminist and postcolonial literary theories, for research in literature and science and — more recently — for renewed formalist analysis and approaches rooted in environmental and disability studies.6 Perhaps the most decisive intervention in this critical afterlife was made by Sandra M. Gilbert and Susan Gubar in 1979, with their argument that Mr Rochester’s mentally ill and imprisoned first wife, Bertha, who inspired their book’s title, The Madwoman in the Attic, is Jane’s ‘double’: ‘she is the angry aspect of the orphan child, the ferocious secret self Jane has been trying to repress ever since her days at Gateshead’.7 This interpretation can seem a key to the novel, making sense of its mix of genres as a sign of internal conflict. Jane Eyre describes — in a realist vein — the social conditions that make it impossible for Jane fully to act upon or even to articulate her desires and ambitions in her own speaking voice as a character; but it also enables those same unruly energies to emerge through the gothic elements of the text that she is imagined as having written — her Autobiography (as the book’s subtitle announces it to be).

Another influential line of analysis was launched by Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak, who in 1985 offered a sharp critique of the role that Bertha, a ‘native subaltern female’, is made to fulfil. For Spivak, Bertha is ‘a figure produced by the axiomatics of imperialism’, a manifestation of the ‘abject … script’ of the colonial discourse that pervaded the linguistic and imaginative materials Brontë had to work with. Across the continuum of imagining between Jane Eyre and Rhys’s Wide Sargasso Sea, this figure (re-named Antoinette in Rhys’s novel) serves as ‘an allegory of the general epistemic violence of imperialism, the construction of a self-immolating colonial subject for the glorification of the social mission of the colonizer’. Jane’s happiness, therefore, comes at the expense of colonial subjects: Spivak takes this to reveal a blindness in readings such as Gilbert and Gubar’s, and more generally in the discourses of Anglo-American feminist individualism.8

Like The Madwoman in the Attic, Spivak’s text generated a cascade of quotation and reprinting, as well as of critical contention which pointed to elements of the novel that it downplays. As Susan L. Meyer noted, Bertha, who is identified as a ‘Creole’ in Jane Eyre, is not a straightforwardly representative ‘native subaltern’ since she comes from a rich, white, slave-owning family.9 Spivak’s response was that her argument still held since ‘the mad are subaltern of a special sort’; more interestingly, she suggested that the simplicities of her analysis, as first put forward, had contributed to its popularity among students and readers of the novel: ‘a simple invocation of race and gender’ was an easier interpretation to adopt than one that would do more justice to the complicated social identities of the participants.10 This observation indicates how critical analysis, readers’ reactions and indeed imaginative re-makings have intertwined in Jane Eyre’s afterlife, creating a vivid instance of a general phenomenon that has been described by Roland Barthes:

Le plaisir du texte s’accomplit … lorsque le texte ‘littéraire’ (le livre) transmigre dans notre vie, lorsqu’une autre écriture (l’écriture de l’autre) parvient à écrire des fragments de notre propre quotidienneté, bref quand il se produit une coexistence.

[Textual pleasure occurs when the ‘literary’ text (the book) transmigrates into our life, when another writing (the writing of the other) goes so far as to write fragments of our own everyday lives, in short, when a coexistence comes into being.]11

Many readers have embraced Jane Eyre in this way, and it is evident that the pleasure of such imaginative coexistence comes, not only from agreement, but also from contestation — as for instance when Jean Rhys’s passionate involvement with the book led her to re-write it from Bertha’s point of view, an imaginative reaction that helped Spivak to frame her critical position. And that critical position has, in turn, both affected readers’ views and nourished new creative responses, such as Jamaica Kincaid’s novel Lucy (1990), in which the governess figure (a modern au pair) is herself from the West Indies. There is a similar chain of creativity prompting criticism prompting further creativity in the way Robert Louis Stevenson’s Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde (1886), which echoes Jane Eyre’s Bertha in its imagining of a monstrous, hidden figure (Hyde), anticipates Gilbert and Gubar’s argument when it joins that figure with an apparently irreproachable public one (Jekyll) to form a single conflicted self. And, again, Gilbert and Gubar’s critical reading has fed into new creative work, such as Polly Teale’s play Jane Eyre (1998), where Bertha always accompanies Jane on stage,12

A peculiarity of the critico-creative afterlife that I have just sketched is the overwhelming monolingualism of its range of attention. As Lynne Tatlock has noted in her recent study, Jane Eyre in German Lands, what has become of the novel in the ‘German-speaking realm remains terra incognita for most scholars working in English’,13 and the same is true of translations and responses in all other languages. Together with the (few) studies there have been of them,14 they tend to be treated as something separate from the real business of understanding and re-imagining the novel. It is writing in English (so the assumption goes) that has the power to determine what Jane Eyre means, and to give it ongoing life in culture: what happens in other tongues is taken to be necessarily secondary, a pale imitation that can safely be ignored. Yet Tatlock’s book is full of illumination, not only of German culture, but also of Jane Eyre. I hope the same is true of the pages that follow; that, as they trace the book’s metamorphoses through translation, and across time and place, they also offer a refreshed and expanded understanding of Jane Eyre — Jane Eyre ‘in itself’, I would say, were it not that, as we have begun to see with the book’s afterlife in English, it is impossible to hold a clear line between the book ‘in itself’, on the one hand, and what has been made of it by readers and interpreters on the other. Interventions like those by Rhys and Spivak change what Jane Eyre is; this is no less the case if they happen to be in other languages, and to have been made by translators. After all, translators are especially intimate interpreters and re-writers, who must pay attention to every word.

As we will discover, Jane Eyre has been read and responded to at least as often, and just as intensely, in languages other than English; and the way the novel has metamorphosed in translation has sharp relevance to the critical issues I have just sketched (and indeed many others, as we will see). When considering Jane Eyre’s feminism, it matters that it was translated by a Portuguese avant-garde feminist for serialization in an alternative Lisbon periodical in the late 1870s, and that it was connected to women’s liberation movements in Latin America in the mid-twentieth century (see Essay 9 below, by Ana Teresa Marques dos Santos and Cláudia Pazos-Alonso, and Essay 5 by Andrés Claro). When considering the representation of Bertha, what has been made of that representation by readers in the Global South, and how they have re-made it through translation, is clearly an issue of some pertinence (see again Essay 5, as well as Essay 1 by Ulrich Timme Kragh and Abhishek Jain, and Essay 3 by Yousif M. Qasmiyeh).

There are material reasons why these connections have not come into focus until now. It takes a particular conjunction of institutional support and technological development to sustain the degree of collaboration and breadth of reference that are presented in these pages. Yet the material conditions that have hampered work like this in the past have also embodied and sustained a particular ideological stance: a belief in the separateness and self-sufficiency of standard languages, especially English, and a corresponding misunderstanding and under-valuation of the interpretive, imaginative, dialogic power of translation. Some recent work in translation studies and comparative and world literary studies has pushed to reconfigure this regime of ‘homolingual address’, as Naoki Sakai has defined it, creating alternatives to what Suresh Canagarajah has called ‘monolingual orientation’ in literary criticism — that is, the assumption (despite all everyday experiential evidence to the contrary) that the default interpretive context, for any work under discussion, possesses ‘a common language with shared norms’.15 Prismatic Jane Eyre, in redefining the novel as a multilingual, transtemporal and nomadic work, shares also in the endeavour to open up critical discussion to more diverse voices. I will return to the theory of language that permeates and emerges from this approach in Chapter II.

The proliferation of textuality generated by Jane Eyre that I have sketched — the carnival of critique, reading, re-making, reaction, response, and adaptation — matters to the translations of the novel, and they in their turn should be recognised as part of it. As André Lefevere has pointed out, people’s idea or ‘construct’ of a given book comes, not from that book in isolation, but from a plethora of sources:

That construct is often loosely based on some selected passages of the actual text of the book in question (the passages included in anthologies used in secondary or university education, for instance), supplemented by other texts that rewrite the actual text in one way or another, such as plot summaries in literary histories or reference works, reviews in newspapers, magazines, or journals, some critical articles, performances on stage or screen, and, last but not least, translations.16

Translations enter into this larger flow of re-writing and re-making, and they are also affected by it, as indeed all the different currents in the ongoing cultural life of the novel may affect one another. Such currents influence the interpretive choices translators make and the way the finished books are marketed and read. They can even bring translations into being: for instance, a successful film version will typically trigger new translations. Jane Eyre is therefore a paradigmatic instance of the argument I made in Prismatic Translation (2019) that translation should always be seen as happening, not to one text, but among many texts.17 The textuality that flows into any given act of translation may include the whole range of other kinds of re-creation; it may also encompass many other sources such as related books in the receiving culture, histories, dictionaries and so on.18

In these pages, we follow Lefevere in seeing any translation of Jane Eyre as happening among the larger penumbra of versions and responses: they will be referred to and discussed at many points in the chapters and essays that follow. Nevertheless, we draw more of a distinction than he does, albeit a porous and pragmatic one, between all this critical and creative ongoing life and the focus of our investigation, which is the co-existence of the novel in its many translations. For the purposes of our study, we adopt the following rules of thumb for deciding whether to count a given text as a Jane Eyre translation. It should be a work intended primarily for reading, whether on page or screen. So we draw a line between the translations that are our focus and the re-makings in other media — such as films, radio versions, and plays — that are less central to our enquiry. It should be a work of prose fiction, so we distinguish between translations on the one hand and reviews and critical discussions on the other. And it should be a work that is offered and/or taken as representing Jane Eyre — indeed, as being Jane Eyre — for its readers in the receiving culture. So the translations are separated out from responses like Wide Sargasso Sea, or versions like Jane Eyrotica or Lyndsay Faye’s Jane Steele (which shadows the plot of Jane Eyre, though the heroine is a murderer). Some of these Eyre-related books have been translated into other languages — erotic versions have had some success in Russia, for instance19 — but such translations are not translations of Jane Eyre, any more than the versions and responses themselves are. Readers of such texts know that what they are getting is something different from Jane Eyre — indeed, that is why they are reading them.

Another way of describing the (porous, pragmatic) line that we draw is that it distinguishes between translation without an article — the loose, variously fluid and figurative phenomenon — from translation with an article, ‘a translation’, that is, a whole work which stands in a particular relationship to another whole work. The entire penumbra of versions and responses can be said to involve translation-without-an-article: for instance, these texts might include translated snippets of dialogue or passages of description, or they might ‘translate’ (in a loose sense) elements of the source into different genres or locations. To adopt the Indian philosophical terms expounded by Ulrich Timme Kragh and Abhishek Jain in Essay 1 below, ‘the dravya (substance) Jane Eyre can be said to exist in different paryāy (modalities) of the source text, adaptations, and translations, which all are pariṇām (transformations) sharing a quality of janeeyreness’. But within this larger range, any text that offers itself as ‘a translation’ is subjected to a tighter discipline. It takes on the task of being the novel Jane Eyre for its readers.

Nevertheless, this distinction has to be pragmatic and porous because what it is for a text to ‘be the novel Jane Eyre for its readers’ is not something that can be determined objectively or uncontentiously, especially not when a wide range of different languages and cultures, with varying translational practices, are taken into account. For instance, an immediate and blatant exception to our rules of thumb is the Arabic radio version by Nūr al-Dimirdāsh, first broadcast in 1965. As Yousif M. Qasmiyeh explains in Essay 3 below, this translation reached a ‘wide and popular audience across the Arabic speaking region’, where access to books ‘was restricted by a range of socio-economic and educational barriers’. It also had a significant influence on later print translations. So, in this context, where radio is doing some of the same cultural work as might be done by print elsewhere, it seems best to count al-Dimirdāsh’s text as a translation. Even with texts that are indubitably printed, uncertainties of definition arise. Indeed, they flourish. Back in 2004, Umberto Eco proposed what looks like it might be an effective — if broad-brush — quantitative measure for distinguishing a text that is a translation from one that is not:

In terms of common sense I ask you to imagine you have given a translator a printed manuscript in Italian (to be translated, let us say, into English), format A4, font Times Roman 12 point, 200 pages. If the translator brings you back, as an English equivalent of the source text, 400 pages in the same format, you are entitled to smell some form of misdemeanour. I believe one would be entitled to fire the translator before opening his or her product.20

Yet, if we applied this principle to our corpus, the number of translations would be radically reduced, not because any of them are twice as long as Brontë’s English Jane Eyre but because many of them are twice as short, or even shorter. We count such abridged texts as translations by following our rules of thumb: they are intended primarily for reading; they are prose fiction; and they take on the work of being Jane Eyre for their readers. In this, we are adopting the classic approach of Descriptive Translation Studies, seeking not to impose on our material an idea of what translation ought to be, but rather to observe and understand what it has been and is: in the words of Gideon Toury, to view translations as ‘Facts of a “Target” Culture’, and to ‘account for actual translational behaviour and its results’.21

It follows that a kind of text that counts as a translation in one culture might not if it appeared in another. In France, there is nothing quite like the first Chinese translation, done by Shoujuan Zhou [周瘦鹃] in 1925, with the title 重光记 [Chong guang ji; Seeing Light Again]: it is only 9,000 characters in length, and cuts many episodes, as suggested by the titles of its four parts: ‘(1) Strange Laugh; (2) Budding Love; (3) Mad Woman; (4) Fruit of Love’.22 Perhaps the nearest French equivalent is that early French review which delighted Charlotte Brontë, written by Eugène Forcade for the Revue des deux mondes in 1848: it is 24 pages long, so about 10,000 words, and it includes a full summary of the novel together with close translation of selected passages. Brontë called this review ‘one of the most able — the most acceptable to the author of any that has yet appeared’, observing that ‘the specimens of the translation given are on the whole, good — now and then the meaning of the original has been misapprehended, but generally it is well rendered’.23 There is no doubt that both texts are involved in translation-without-an-article. And if we were to take them, the Chinese translation and the French review, abstract them as much as possible from their respective cultures and look at them side by side, we might well conclude that the review gives the fuller impression of what Brontë wrote.

But readers of the Revue des deux mondes did not think they were being offered a translation. They knew they were reading a review — not only because Forcade frames and permeates the summary and extracts with his own opinions of the novel and indeed of much else, including the 1848 French revolution, but also because, for mid-nineteenth-century French readers, reviews were established as a genre distinct from translations: though a review might well include passages of translation, it was not itself a translation. The 1925 Shanghai publication, on the other hand, was part of a ferment of translation of English and European texts in China in the early decades of the twentieth century, during which there was also much debate about different modes of translation and the language appropriate to it. A range of kinds of text were therefore received under the umbrella term yi 譯 (translation), with重光记 [Chong guang ji; Seeing Light Again] among them.24 So, unlike the French review, the Chinese text is a piece of fictional writing that is offered and taken as being a translation, as bodying forth Jane Eyre for its readers; and in fact it was the only text in Chinese that did so until the publication of a fuller version ten years later: 孤女飘零记 [Gunv piaolingji; Record of a Wandering Orphan] by Wu Guanghua [伍光建]. So it seems to make best sense to count Chong guang ji as a translation, while not counting Forcade’s review.

Given all this variability and overlap, why seek to distinguish translations from other kinds of re-writing at all? One reason is that it enables us to count them, and to locate them in time and space, and therefore to create the interactive maps and other visualisations that I present in Chapter III. Even though the category that we have defined is fuzzy, there is still value in mapping it, and especially so when the synoptic picture provided by the maps is nuanced by the detailed local investigations conducted in the essays. A second reason has to do with the kind of close reading that translations embody and enable. Because translations stick so tightly to the source text, trying to mean the same, or do the same, with different linguistic materials in different times and places, they repay very close comparative attention. As Jean-Michel Adam has observed:

La traduction présente … l’immense intérêt d’être une porte d’accès à la boîte noire de la lecture individuelle et secrète qui fait que le même livre est non seulement différent pour chaque lecteur, mais qu’il change même à l’occasion de chaque relecture et retraduction.25

[Translation has the enormous interest of giving us an entry into the black box of individual, secret reading which causes the same book, not to be only different for each reader, but to change with every re-reading and re-translation.]

Clive Scott has made a similar point: ‘translation is a mode of reading which gives textual substance to reader response’.26 Because this substantiated reader response, this metamorphic reading and re-reading, translation and re-translation, is done in different moments, cultures and languages, it also gives us a uniquely precise view of the gradations and entanglements of historical, cultural and linguistic difference. This will be amply illustrated in the chapters and essays to come.

The third reason, which follows closely from the second, is that it is only by distinguishing translations from the mass of other Eyre-related textuality that we can bring into focus the distinctive, paradoxical challenge that — like translations of any text—they pose to understanding and interpretation. A translation stakes a claim to identity with the source text: to be Jane Eyre for the people who read it. And yet that claim is in many respects obviously false, most obviously of all, of course, in the fact that the translated Jane Eyre is in a different language. Pretty much every word, every grammatical construction, and every implied sound in a translation will be different from its counterpart in the source. What is strange is that it is in practice this blatant and unignorable difference which enables the claim to identity to be made. It is the perception of language difference that generates the need to be able to say or write something that counts as the same in a different language; and it is the reality of language difference that enables a translation to take the place of its source, since the source will be, for many readers in the receiving culture, difficult or impossible to understand. So, paradoxically, the claim to identity is made possible by the very same factor that announces it to be untrue. To quote again from Prismatic Translation, the book that provides much of the theoretical groundwork for Prismatic Jane Eyre, this is ‘the paradox of all translation’.27

From the 1850s onwards, that is, in the early years of Jane Eyre’s expanding life in translation, this paradox was confronted by European lawyers, who were trying to establish international copyright agreements that would include translations. As a scholar of the issue, Eva Hemmungs Wirtén, has put it:

The crux was that the international author-reader partnership also required the multiplication of authorship, and when the need for another author — a translator — was a prerequisite for reaching new readers, the work in question was in danger of alienation from the author. Something happened when a text moved from one language into another, but exactly what was it? Was it reproduction only, or creation of a new work, or rewriting?28

The debates culminated in the Berne Convention of 1886, which adopted the view that translations were merely reproductions, no different from a new edition. In consequence, ‘authors had the right to translate themselves or authorize a translation of their works within ten years of the first date of publication in a union nation’.29 Wirtén goes on to explain that national interests played a large part in this decision. States such as France, whose literatures were much translated, sought to expand the rights of the source-text authors who were their citizens. On the other hand, states such as Sweden, which imported many books through translation, wanted to grant as much liberty as possible to translators, as a document of 1876 asserts:

För ett folk, hvars språkområde vore så inskränkt, som det svenska, kunde icke ett band på öfversättningsfriheten undgå att verka hämmande på spridning af kunskap och upplysning. Behofvet för ett sådant folk att fullständiga egen litteratur med öfversättningar från utlandets bättre verk vore oändligt mycket större, än det som förefunnes hos folk med vidssträckt språkområde och betydligt rikhaltigare litteratur, än den Svenska.

(For a people whose language is so small and geographically limited as the Swedish, any restriction on freedom of translation could not but have a negative impact on the dissemination of knowledge and education. The need for such a people to complete its own literature by translations of the better works from abroad is infinitely greater than what it is for people with a widespread language and considerably richer literature than the Swedish.)30

At Berne, the French view won out over the Swedish; but the debates were not silenced by this triumph of literary power-politics. A revision to the agreement, made in Berlin in 1908, allowed the Swedish view back in, granting translations copyright protection of their own, whether they were authorized or not. This provision was in considerable tension with the protection that continued to be granted to source texts. Wirtén concludes that the Berlin Convention ‘implemented a paradox. On the one hand, the rights of the author included translation, but on the other, the translation emerged as a separate work.’31

The paradox of translation, as it reared its head in Berlin, reveals the dead end of the terms in which translations and source texts were defined in those debates — terms that persist in much discussion to this day. A source is not a determinate entity that can be either reproduced in translation or not. It consists, not only of its printed words and punctuation, but of all that they mean, and all that they do. As Roland Barthes, Stanley Fish, and other literary theorists have demonstrated in manifold ways since the 1960s, the meaning and affect of a work are not simply given in the text but emerge through the collaborative involvement of readers.32 Translators are readers. What is more, as we have seen, their work belongs with those other kinds of re-writing, including literary criticism, that are accepted as characterising and illuminating the book, as subjecting it to continuous rediscovery and reconfiguration. It follows that a translation cannot be judged by how well it ‘reproduces’ or ‘is faithful to’ its source, for translation is involved in determining what that source is.

A series of thinkers in Translation Studies have contributed to the view that I am presenting. Focusing on works in classical Greek and Latin, Charles Martindale argued (three decades ago now) that it is misconceived to ask whether a translator has captured what is ‘there’ in the source, since ‘translations determine what counts as being “there” in the first place’. Developing a similar point from his work on nationalist constructions of the Japanese language, Naoki Sakai demonstrated the incoherence of trying to decide whether a translation has or has not successfully transferred the source’s meaning, since you cannot define what you think that meaning to be until you have translated it: ‘what is translated and transferred can be recognized as such only after translation’. In short, in the crisp, recent formulation by Karen Emmerich, ‘each translator creates her own original’.33 Reading translations in connection with their source, therefore, is not only to engage in transnational literary history and comparative cultural enquiry, though we do a great deal of those two things in the pages that follow. It is also to confront a basic ontological question: what is Jane Eyre?

What is Jane Eyre?

If we focus on the translations as just defined, that is, on the texts that make a claim to be Jane Eyre, we discover not only an enormous amount of textuality — several hundreds of translations, several scores of languages, many millions of words — but also a great deal of variety. First, as we have seen, there is variety in size. Many of the translations are roughly the same length as the source (i.e., about 186,000 words, or 919 generously spaced pages in the first edition); none, so far as we have been able to discover, are significantly longer. But many are shorter, sometimes very much so. Zhou Shoujuan’s first Chinese translation of 1925, at 9,000 characters, may be an extreme case, but is very far from being the only one. The first translation into an Indian language, Tamil, done by K. Appātturai [கா அப்பாத்துரை] in 1953, with the title [ஜேன் அயர்: உலகப் புகழ் பெற்ற நாவல்] (Jēn Ayar: Ulakap pukal̲ per̲r̲a naval; Jane Eyre: A World-Renowned Novel), was 150 pages. The first Italian translation, with an anonymous translator and the title Jane Eyre, o Le memorie d’un’istitutrice (Jane Eyre or the Memoirs of a Governess) was 40,000 words shorter than Brontë’s English text. The first version in French, Jane Eyre ou Mémoires d’une Gouvernante (Jane Eyre or Memoirs of a Governess), published in Paris and Brussels in 1849, written by Paul Émile Daurand Forgues under the pseudonym ‘Old Nick’, and serialized virtually simultaneously in two newspapers and a literary journal, consisted of 183 pages (I say ‘version’ here because this text’s status as ‘a translation’ is especially controversial, an issue that I explore further below).

As these instances suggest, abridgement is a common feature of first or early translations, and especially so when they are done into languages and cultures distant from British English. As Kayvan Tahmasebian and Rebecca Ruth Gould observe of the Iranian context in Essay 8, where they build on an idea of Antoine Berman’s, it is often the case that successive translations gravitate towards equality of length with the source text. New translations can differentiate themselves from their predecessors by claiming greater accuracy; equally, the passing of time since the mid-nineteenth century has seen enormous growth in the global use of English, as well as in technologies for checking translations against their sources and one another, and in institutions for evaluating them (such as prizes). But other trends push in the opposite direction, and keep abridgements coming. With its childhood beginning, clear narrative line, assertive voice and elements of gothic and romance, Jane Eyre is in itself an attractive prospect for re-making as a children’s book; and, as it became ever more widely celebrated, market forces must have started to beckon too. In Germany, as Lynne Tatlock has shown, adaptations for children — and especially for girls — date back to as early as 1852 and proliferated through the later nineteenth century, taming the novel by changing it in various ways, including killing Mr Rochester or omitting him entirely.34 Examples of translations aimed at the same demographic are those done into Russian, anonymously, in 1901; into Turkish in 1946 by Fahrünnisa Seden; into Italian, anonymously, in 1958; into Greek in 1963 by Georgia Deligiannē-Anastasiadē; into Portuguese in 1971 by Miécio Táti (published in Rio de Janeiro); into Hebrew in 1996 by Asi Weistein (published in HaDarom in Israel/Palestine); and into Arabic in 2004 by Ṣabri al-Faḍī (published in Cairo). For similar reasons, abridged translations with parallel text, thesauruses and other learning aids have been made as part of the international industry in English-language tuition: for instance, into Lithuanian by Vytautas Karsevičius (1983); into Hungarian by Gábor Görgey and Mária Ruzitska (1984); and into Chinese by Guangjia Fu [傅光甲] (2005).35

Variation in length, then, is not only variation in length. It intersects with differences of audience, use, genre and style. As Yunte Huang explains in Essay 12, Zhou Shoujuan shrank Jane Eyre so radically as part of his endeavour to translate it into the conventions of ‘the School of Mandarin Duck and Butterfly … a genre of popular fiction’. The first, abridged Italian translation of 1904 reveals the influence of its target audience too, when it presents itself as meeting a demand from mothers and girls (‘e madri e ragazze’) to read the celebrated novel, in line with the aim of the imprint in which it appeared, Biblioteca Amena (‘Agreeable Library’), to offer ‘buone e piacevoli letture accessibili a tutti e a tutte’ (virtuous and pleasant reading accessible to all, men and women, girls and boys’). In this pursuit, the 1904 translation does not cut any episodes of dubious virtue: for instance, the story of Mr Rochester’s affair with Céline Varens remains intact. Instead, it consistently simplifies the complexities of Brontë’s style, and hence of Jane’s voice. To give one indicative instance: after the dramatic episode of the fire in Mr Rochester’s bedroom in Chapter 15, the English Jane narrates as follows:

Till morning dawned I was tossed on a buoyant but unquiet sea, where billows of trouble rolled under surges of joy.

The 1904 Italian Jane, on the other hand, says this:

Era giorno quando mi pareva di sentirmi portata via da onde torbide mescolate ad onde chiare.

[It was dawn when I seemed to feel myself carried away by turbid waves mixed with clear waves.]36

Shortening and simplifying go hand in hand, as Jane Eyre is translated into a kind of language that can be readily shared by its targeted readers.

The 1849 French version by ‘Old Nick’, Jane Eyre ou Mémoires d’une gouvernante [Jane Eyre or Memoirs of a Governess], took a different approach. It was made for serial publication, appearing in 27 instalments in the Paris newspaper Le National from 15 April to 11 June, and almost simultaneously in Brussels, in three monthly numbers of a literary magazine Revue de Paris (April–June), and in daily segments (though with several interruptions) in the newspaper L’Indépendance belge from 29 April to 28 June.37 It was also published in book form in Brussels the same year, and later in Paris, in 1855.38 The rare-book expert Jay Dillon, who discovered the serialization in Le National, has shown that it must have been the first publication, and argued that the Brussels printings are likely to have been piracies.39 Certainly, the Brussels-based Revue de Paris, which was an imitation of the famous journal of the same name published in Paris, typically plagiarized articles from Paris publications.40 In this context that was itself strangely, dubiously translated, this Revue de Paris published in Brussels, Jane Eyre took its place among other serialisations, short stories, reviews, essays on history, the text of Alfred de Musset’s play ‘Louison’ and an essay on the Louvre by Théophile Gautier. In the two newspapers, meanwhile, it appeared among round-ups of domestic politics and items of economic and international news. Jane Eyre was adapted for Le National by a man of letters, Paul Émile Daurand Forgues, who was becoming increasingly prominent as a reviewer and translator of British fiction, and whose pseudonym ‘Old Nick’ (a nick-name for Satan) perhaps suggests the devilish liberties he felt entitled to take as he mediated between the two literary worlds.41

In shortening Jane Eyre for newspaper serialization, perhaps under pressure of time,42 Old Nick (inevitably) also altered its style and genre. It becomes a letter — apparently one, extremely long letter divided into 27 chapters — addressed to a ‘Mistress T…….y’, whom Jane, to begin with, calls her ‘digne et sévère amie’ (‘honoured and austere friend’), but who, in the warmth of narration, becomes ‘ma chère Élisabeth’ (‘my dear Elisabeth’) by the start of Chapter 2.43 The chapters are all of fairly uniform, short length, one for each instalment in Le National; this might also be felt to suit the idea of a letter being written sequentially. We could decide that this reconfiguration of the narrative loses the frank challenge of Jane’s voice which, in Brontë’s English, throws itself equally at all readers. Yet the change also brings Jane Eyre into the interpretive frame of the epistolary novel, a form long established in France and employed by writers such as Rousseau and Laclos: this might well seem a welcoming move to make when introducing a text to a new culture. We can, then, view it as part of the complex process of translation, not only into a language but into a particular genre, medium and set of expectations.

Seeing the shift of narrative form in this way generates a kind of heuristic counter-current. It makes us freshly aware of the distinctiveness of Brontë’s choice precisely not to organise Jane Eyre as an epistolary novel — or indeed as an impersonal, third-person narrative like its closest precedent in English, Charles Dickens’s Oliver Twist (1837–39) — but instead to create that compelling first-person voice, which makes frequent addresses to an unspecified reader without (puzzlingly, challengingly) having any explicit moment or purpose for the narration. Part of the significance of Jane Eyre — or any text — in a transnational and multilingual perspective is created by the forms that it seems to be asking to take on, the shapes that it might itself very well have adopted, but did not. In translation, these shadow forms can step forward and impose themselves on the substance of the text (we will see other examples in the chapters and essays that follow). As they do so, they fulfil what might be described as a potential latent in the source text while, in that very same action, giving salience to the fact that the potential was not realised in the source text itself. This paradoxical dynamic, of what might be called realisation through what might equally be called betrayal, can be found in all translation, and it is one of the engines that power the prismatic proliferation of Jane Eyre, or any work. The existence of the Old Nick version must have encouraged Noëmi Lesbazeilles-Souvestre and her publisher D. Giraud to repair Old Nick’s realisation/betrayal by producing her more word-for-word translation in 1854, claiming ‘l’Autorisation de l’Auteur’ (‘the Authorisation of the Author’) — though no evidence has survived to indicate whether or not any such authorisation was in fact given. And the existence of her translation must in turn have encouraged a rival publisher, Hachette, to re-issue the Old Nick version as a book in 1855 in its ‘Bibliothèque des chemins de fer’ (‘Railway Library’), re-asserting the interest of the different potentials that it fulfils.

Old Nick uses the epistolary voice to summarise some parts of the novel, introducing a more detached tonality of ethical reflection, while at the same time reproducing other sections very closely. Here is an instance of the braiding of the two modes, from the young Jane’s conversation with Helen Burns in Chapter 6. Brontë wrote:

‘But I feel this, Helen; I must dislike those who, whatever I do to please them, persist in disliking me; I must resist those who punish me unjustly. It is as natural as that I should love those who show me affection, or submit to punishment when I feel it is deserved.’

‘Heathens and savage tribes hold that doctrine, but Christians and civilised nations disown it.’

Old Nick fuses the first sentence into a summary that represents the immediately preceding exchanges too, before switching to close translation:

J’essayai de démontrer à Helen que la vengeance était non-seulement un droit, mais un devoir, puisqu’elle sert de leçon à quiconque l’a méritée.

« Il est aussi naturel de résister à l’injustice que de haïr qui nous hait, que d’aimer qui nous aime, que d’accepter le châtiment quand le châtiment est équitable.

—Ainsi pensent les sauvages, et les païens pensaient de même, répondit tranquillement Helen. Mais les chrétiens et les peuples civilisés repoussent et désavouent cette morale.44

[I tried to prove to Helen that revenge was not only a right, but a duty, since it serves as a lesson to whoever has deserved it.

‘It is as natural to resist injustice as to hate those who hate us, to love those who love us, and to accept punishment when punishment is fair.’

‘So think savages, and pagans think the same,’ Helen replied calmly; ‘but Christians and civilised nations reject and disavow this morality.’]

The English Jane’s repeated ‘I feel’ is replaced by impersonal statements of principle and justice, and her tolling ‘I’s dissolve into infinitive constructions: the novel of feeling is moved towards the novel of philosophy. Inga-Stina Ewbank, in her pioneering and still helpful survey of some of the early European Brontë translations, sees this kind of adjustment as being simply a matter of loss, the imposition of ‘a cooling layer between experience and reader’, reducing Jane’s ‘ardour’ and weakening her ‘force’.45 Yet Old Nick finds other ways of introducing intensity, adding the phrase about hating those who hate us, and doubling ‘disown’ into both ‘repoussent’ (‘reject’) and ‘désavouent’ (‘disavow’). Other touches too suggest a translator imagining his way into the scene and sensing how best to recreate it, for the context at hand, with the linguistic and stylistic resources at his disposal: for instance, the addition of the speech description ‘répondit tranquillement Helen’ (‘Helen replied calmly’). Brontë is sparing of such tags, having unusual confidence in the power of her dialogue to make itself heard by her readers, almost like a play script. We could accuse Old Nick — in the Ewbank vein of criticism — of lacking that same daring; but equally, his insertion of the adverb underlines the distinctiveness of Helen’s character, accentuating the difference between her view of things and Jane’s.

As this brief analysis suggests, Old Nick’s version, despite its abridgements, remains a perceptive work of translation. The same holds true on the larger scale of the cuts he makes to the plot. For the most part, what goes are sections that many readers would probably choose to give up if they had to. Jane’s visit to Mrs Reed’s deathbed is replaced by the receipt of a letter bearing the sad news, and enclosing the note from her uncle John Eyre — which Mrs Reed had suppressed — announcing his intent to make Jane his heir. So we lose the perhaps slightly laboured satire of the grown-up Eliza and Georgiana while the discovery that is needed for the plot is neatly preserved. The long descriptions of the house party with the Ingram and Eshton ladies are reduced to this:

Je ne vous les décrirai pas; à quoi bon? Avec des nuances plus ou moins prononcées, c’était chez toutes ces fières créatures le même air de calme supériorité, la même nonchalance dédaigneuse, les mêmes gestes appris, la même grâce de convention.

[I won’t describe them: what would be the point? With more or less distinctive nuances, all of these proud creatures had the same air of calm superiority, the same disdainful nonchalance, the same studied gestures, the same conventional grace.]46

The back story of Mr Rochester’s affair with Céline Varens is condensed with a similar critical justification:

Je ne vos répéterai point cette histoire, après tout assez vulgaire, d’un jeune et riche Anglais séduit par une coquette mercenaire appartenant au corps de ballet de l’Opéra. Il s’était cru aimé, il s’était vu trahi.

[I won’t rehearse this story, after all a pretty vulgar one, of a young, rich Englishman seduced by a mercenary coquette from the corps de ballet at the Opera. He had believed himself loved; he had seen himself betrayed.]47

In these self-referential phrases (‘I won’t describe’, ‘I won’t rehearse’), the narrative decisions of the French Jane about which bits of her experience to relate to her dear Elizabeth are merged with the translatorial decisions of Old Nick vis-à-vis the English novel. The letter-writer representing her life-story becomes a figure for the translator representing his source. To echo a phrase from Theo Hermans, this shows the translator exhibiting his ‘own reading’, and marking its difference from other possible interpretations.48 As the letter-writer chooses to concentrate on what seems most important, so too does the translator; and as she has an eye to the expectations of her readership, so too does he, for the sections cut include those least likely to impress readers familiar with Balzac or Stendhal. The most striking omission is the scene of Bertha’s incursion into Jane’s bedroom at night, just before her planned wedding — especially as the intimations of Bertha’s presence up to that point, as well as the encounter with her after the interrupted wedding, are all fully represented. It is possible to imagine a mix of reasons for this choice: perhaps Old Nick felt the scene to be too melodramatic, and perhaps he also felt it risked spoiling the surprise of the imminent final reveal.

Nevertheless, the main lines of the narrative remain, and many key scenes such as the ‘red-room’ are attentively translated. Forcade, in his 1848 review, had drawn attention to the way Jane and Mr Rochester become progressively attached ‘de causerie en causerie, de confidence en confidence, par l’habitude de cette camaraderie originale’ (‘from chat to chat, from confidence to confidence, by the habit of this unusual camaraderie’), and Old Nick seems to have felt the same, for the intimate, jousting conversations between the pair are what he most fully translates, and the developing stages of their relationship are what he most closely tracks. Indeed, his tighter focus enables suggestive structural echoes to emerge which may be muffled in the fuller treatment of Brontë’s text. For instance, in Chapter 15 of the source (which becomes Chapter 7 in Old Nick’s version), Jane saves Mr Rochester from burning in his bed, after which the two of them find it hard to part: ‘“Good night then, sir,” … “What! … not without taking leave” … “Good night again, sir” … he still retained my hand … I bethought myself of an expedient … he relaxed his fingers, and I was gone’.49 In the next chapter she discovers, after a lonely day of puzzled waiting, that Mr Rochester has in his turn departed, leaving Thornfield to stay with a house party some distance away, and is not expected to return at all soon. Reading Brontë’s English, it is possible to be struck by and reflect upon this sequence of intimate lingering and departure followed by larger-scale departure and lingering; but Old Nick spotlights the connection with a repeated word. Of leaving Mr Rochester’s bedroom, Jane writes ‘je le quittai’ (I left him); five pages later she learns from Mrs Fairfax that, where Mr Rochester is staying, he will be with the lovely Blanche Ingram, whom he ‘ne quitte pas volontiers’ (‘never leaves willingly’).50 The surge of jealousy which, in Old Nick as in Brontë, takes up the next few pages is heralded by this verbal echo, which hints that Jane may be prey to gnawing thoughts about the consequences of her act of leaving: if she had not left him, perhaps he would not have left the house; or, since she did leave him, perhaps he now will not leave Blanche.

Observing these changes of form and alterations of emphasis which emerge through translation, it is possible to lament, with Ewbank, that this is ‘not our Jane Eyre any longer’. Yet Ewbank’s phrasing, with its confidently possessive first-person plural, reveals with unusual clarity the nationalist tonality of this mode of translation criticism, in which anything that strikes the critic as significantly different from the source text is marked down as a loss. The assumption underlying this familiar, though unrewarding, line of critique is that success in translation is impossible, because success is taken to mean identity, and translations are by definition different from their sources even as they claim some form of sameness. But once you open yourself to the recognition that the work, Jane Eyre, has an existence beyond its first material embodiment in 186,299 particular words (not all of them English words, as we will explore further in Chapter II), the kinds of metamorphosis that occur as the work re-emerges in different linguistic forms can become more interesting. This Jane Eyre is not ‘our’ (English readers’) Jane Eyre as idealised by Ewbank, but then the actual Jane Eyre that is read and lives on in the minds of real English readers is not that either: it encompasses all sorts of varying perceptions, obsessions, expansions and forgettings, as Lefevere pointed out. The idea of there being a consistent, clearly recognisable ‘our Jane Eyre’ is a nationalist and class-based projection, a striking instance of the regime of ‘homolingual address’ identified by Sakai. It is reinforced by the apparent material sameness of the book as it has been reprinted over the decades in English (even though, as Paola Gaudio outlines in Essay 2, there have also been notable textual variations in successive editions): the apparent solidity of print on paper pushes out of view the varied realisations that the work has in fact had in the imaginings of generations of anglophone readers. As we saw with Jean-Michel Adam, part of the excitement of working with translations is that they provide visible evidence of that interpretive plurality which otherwise remains, to a large extent, hidden in readers’ minds.

Nevertheless, one can sympathise with the shock felt by Charlotte Brontë’s friend and fellow-novelist Elizabeth Gaskell when sent the book of Old Nick’s version in 1855 by the publisher Louis Hachette. She was startled by the ‘offensive’ pseudonym of the translator, and distressed also by the degree of the abridgement:

Every author of any note is anxious for a correct and faithful translation of what they do write; and, although from the difference of literary taste between the two nations it may become desirable to abbreviate certain parts, or even to leave them out altogether, yet no author would like to have a whole volume omitted, and to have the translation of the mutilated remainder called an ‘Imitation’.51

Here we can see, not only Gaskell’s loyalty to her friend, together with her emotional investment in the book and her sense of her own professional status, but also the power to provoke that the work of translation, and especially the claim to count as a translation, can possess. Gaskell feels the thrust of this claim even though, as she notes, Old Nick’s version was advertised as being ‘imité’ (‘imitated’) from Currer Bell, rather than ‘translated’; it was also — on its earlier appearances in Le National and Revue de Paris — described as a ‘réduction’ (‘reduction’), not a translation. As we have been discovering, the borderlines between these terms are in general porous and contested; and they were conspicuously so in French literary culture in the mid-nineteenth century. The prevailing definition of a translation excluded reviews, as we have seen; but on the other hand there was wide acceptance that translations, especially from non-romance languages, needed a fair amount of licence to adapt their sources to the norms of French, and the demands of the publishing market, too, promoted abridgements and adaptations. Four years after his version of Jane Eyre, Old Nick translated Nathaniel Hawthorne’s The Scarlet Letter: the text was no less cut and tweaked than his imitation or reduction of Brontë’s novel, and the changes were welcomed by a journal, the Revue britannique:

Plus d’un passage nous a paru supérieur à l’original, car il fallait pour le rendre une certaine adresse, lutter avec des phrases un peu redondantes, prêter enfin au romancier américain le goût qui lui fait parfois défaut.52

[More than one passage struck us as being superior to the original, because a certain dexterity was required to bring it across, to wrestle with somewhat over-expansive sentences, and to lend the American novelist the taste that he sometimes lacks.]

Yet this book was advertised on the title page as being, not reduced, nor imitated, but ‘traduit par Old Nick’ [translated by Old Nick].53

Looking only at this French context, then, we already get a vivid sense of the instability of the definition of ‘a translation’. In consequence, we might choose to discount the markers ‘imité’ and ‘réduction’, and view Old Nick’s Jane Eyre as a translation — as I have been doing — though we might equally choose to accept them, since, after all, they were the terms adopted by him (or his publishers): this is the line taken by Céline Sabiron in Essay 4 below. However, on the larger scale of transnational literary history, those labels, as well as Gaskell’s protest, counted for nothing as Old Nick’s version was established as a translation by later translators. During 1850–51, Spanish texts titled Juana Eyre. Memorias de un Aya [Jane Eyre: Memoirs of a Governess] appeared in several locations in South America: Santiago de Chile, Havana and Matanzas in Cuba, and La Paz in Bolivia. The text was initially serialised in newspapers (in El Progreso, Santiago; Diario de la Marina, Havana; La Época, La Paz), though it also appeared in volume form. The conduit for this speedy and distant proliferation of Jane Eyres was a Paris-based publishing enterprise connected to the Correo de Ultramar, a magazine which conveyed literary and fashion news to Spanish-speaking countries globally.54 In 1849, ‘Administración del Correo de Ultramar’ published a Spanish translation of Old Nick’s French version of Jane Eyre, crediting Old Nick (spelt ‘Oldt Nick’ on the title page) as author and making no mention of Brontë.55 This anonymous translation is the text that was reproduced in Chile, Cuba and Bolivia. Through this process the English source has been erased, and Old Nick’s French has become the ‘original’; but still, the Spanish text is figuring as the translation of a novel called Jane Eyre.

In the Netherlands in 1849, and in Denmark and Saxony (a German kingdom) in 1850, translations were published with subtitles that echoed Old Nick’s, though now Currer Bell was credited as author: Dutch, Jane Eyre, of Het leven eener gouvernante; Danish, Jane Eyre, eller en Gouvernantes Memoirer; German, Jane Eyre: Memoiren einer Gouvernante. Of these, the German publication, by Ludwig Fort, turns out to be taken from Old Nick’s version; and so too does a Swedish translation from 1850, even though it draws its subtitle from Brontë and not Old Nick: Jane Eyre: en sjelf-biographie. So, across Europe and South America in the first few years of the novel’s life, you could open a book called Jane (or Juana) Eyre and be as likely to find a translation of Old Nick’s text as of Brontë’s. This arrogation of Old Nick’s text to the status of translation continued in the years that followed: for instance, the 1857 Russian Dzhenni Ėĭr, ili zapiski guvernantki [Jane Eyre, the memoirs of a governess] was translated by S. I. Koshlakova from Old Nick’s text.56 To Emmerich’s observation that ‘each translator creates her own original’, we can now add that many factors collaborate in the workings of literary history to determine the form of an original and what counts as a translation of it.

These complex strands of what is (so far) only a tiny part of Jane Eyre’s translation history show the importance of institutional and material factors such as connections between publishers and the physical movements of texts — what B. Venkat Mani has called ‘bibliomigrancy’.57 Such factors include censorship: as we will see in Essay 17 below, by Eugenia Kelbert, Vera Stanevich’s 1950 Russian translation was cut by the Soviet censor, with passages relating to Christianity especially being removed; and as Ana Teresa Marques dos Santos and Cláudia Pazos Alonso show in Essay 9, the 1941 Portuguese translation by Mécia and João Gaspar Simões, which came out during the dictatorship of António de Oliveira Salazar, skipped passages that express Jane’s desire for greater liberty. Meanwhile — as Andrés Claro reveals in Essay 5 — in Barcelona, Spain, in 1943, the republican Juan G. de Luaces was translating so as to hint at the rebellious energies in the novel that could not be openly expressed under the regime of Francisco Franco. As all three essays suggest, and as other work on translation and censorship has also shown,58 there is no hard distinction between state coercion on the one hand and individual choices on the other. Marques dos Santos and Alonso discuss an anonymous Portuguese translator writing in 1926, i.e., before Salazar, who took ‘a liberdade de cortar desapiedadamente tudo quanto pudesse impedir a carreira dos eventos para o desenlace final’ [the liberty to cut ruthlessly everything that could prevent the flow of events towards the final denouement]. This translator was not subject to state censorship, but was still feeling societal pressures from outside as well as interpretive impulses from within. The same is true of Zhou Shoujuan (周瘦鹃), Old Nick and the anonymous 1904 Italian translator, as we have seen in this chapter. Any act of translation involves some negotiation between what a translator might wish to write and what is likely to be acceptable in their publishing context.

Our glimpse of a small part of Jane Eyre’s complex life in translation also reveals the productiveness of a prismatic approach; that is, of recognizing that translation generates multiple texts which ask to be analysed together.59 All the texts that I have mentioned so far, all the texts discussed in the rest of this volume, and indeed all the many translations that we do not have room to discuss — all are manifestations of, and contributions to, the world work that Jane Eyre has become and is becoming. As Clive Scott has put it:

The picture of the translational world that we want to generate is one in which each translation is viewed not as a tinkering with a master-copy, nor as a second order derivation, but as a composition, whose very coming into existence is, as with the ST [source text] before it, conditional upon its being multiplied, on its attracting variations, on its inwardly contesting, or holding in precarious tension, its own apparent finality.60

Each new translation establishes a relationship to Jane-Eyre-as-it-has-been-hitherto, and especially to the aspects of the world Jane Eyre that have been knowable to the translator: the source text they have used (whether it is in English or, in the case of relay translation, another language), and the related texts and ideas that have flowed into the process of translation. At the very same moment, the new translation becomes part of the world Jane Eyre, changing it, and also creating a momentum that may help another translation into being, as Old Nick’s version helped generate the texts that derived from it, such as the Spanish translation that spread to South America and Lesbazeilles-Souvestre’s rival French translation. This is somewhat similar to the dynamic that reigns in English-language contexts (as we saw at the start of this chapter) when the novel is discussed in reviews, academic criticism, debates in book groups or conversations among friends, each new opinion tending to generate another. But what is different about those forms of response is their relationship to the idea of Jane Eyre, which is constructed by the organizing power of genre. This relationship is manifest both in their own rhetoric and in the way they are received. They present themselves, and are taken, not as staking a claim to be Jane Eyre but merely as saying something about it. They therefore seem not threaten an idea of ‘the work itself’ as being embodied in the printed words of the English book. In fact, new critical interpretations do alter the words of Jane Eyre, but the difference they introduce is invisible. Since Gilbert and Gubar, and since Spivak, the novel has changed, for its words have become part of (we might say) new languages — the languages of feminist and postcolonial critique. Any critical intervention, or any version, has the power to transform the novel in the same way. And such ‘new readings’, as we tend to call them, even though they are in fact re-writings, are helped into being by pervasive shifts in culture and language that are perpetual and inevitable. As it is reprinted and re-read in English, Jane Eyre is in fact being continuously translated. The form of the printed words and punctuation may not alter (or not very much), but the language that surrounds them changes, which is to say, the language that Jane Eyre is taken as being ‘in’.61

Comparison with another kind of continuity through change can help to illuminate the continuing and indeed expanding existence of Jane Eyre through translation. In Reasons and Persons, the philosopher Derek Parfit dismantles the view that personal identity is ‘distinct from physical and psychological continuity’, a ‘deep further fact’ that must be ‘all-or-nothing’. Instead, what matters are the links between past, present and future experiences, connections such as ‘those involved in experience-memory, or in the carrying out of an earlier intention’. For me to continue being me, it is not necessary for anything to be unchanged between me in the future and me now or as I was at any point in the past: rather, there needs to be a sequence of bodily and experiential links. For instance, no bit of hair on my head may be the same as in my childhood, but it has replaced the hair that replaced the hair (etc.) that I had in that distant period. Likewise, I may not remember what I received for my tenth birthday, but I have a memory of a time when I had a memory of a time when (repeat as often as necessary) I could remember it. What follows is that there is no absolute divide between me and other people, since many experiences are shared. In a beautiful and famous passage, Parfit describes how his sense of himself changed when he had reasoned his way from the first to the second view: ‘when I believed that my existence was such a further fact, I seemed imprisoned in myself. My life seemed like a glass tunnel, through which I was moving faster every year, and at the end of which there was darkness. When I changed my view, the walls of my glass tunnel disappeared. I now live in the open air. There is still a difference between my life and the lives of other people. But the difference is less.’62

Of course, there are many distinctions to be drawn between a person and a literary work, and also a great many intricacies to Parfit’s argument beyond the sound-bite that I have given here. Nevertheless, there are four aspects of his view that are comparable to the argument I am making about texts and translations. The first is that selfhood can consist of a series of linked experiences together with physical continuity: in our case, Jane Eyre inheres in the networked experiences of its readers, including the readers of its texts in translation which, like all English editions, are joined by a sequence of physical links to Brontë’s manuscript. Second is the recognition that identity is not ‘all-or-nothing’: for us, the texts of Old Nick’s Jane Eyre or Zhou Shoujuan’s 重光记 are linked enough to, and generate enough shared experiences with, Brontë’s Jane Eyre to count as belonging to the same work, as being an instance of it. Third is the overlap between experiences that are mine and experiences that are those of other people: this is like the overlap between Jane Eyre and works like Forcade’s review or Wide Sargasso Sea which, while not being Jane Eyre, share some of its features. Finally, there is what happens when you see things in this way. Instead of there being a glass wall around an idealized English Jane Eyre (‘our Jane Eyre’, as Ewbank put it), separating it off from its translations which by definition will never match up to it, nor be as good — instead of that isolationist and dismissive view — we can now see that the translations share in the co-constitution of Jane Eyre, enabling what Walter Benjamin, in ‘Die Aufgabe des Übersetzers’ (‘The Task of the Translator’), called its Fortleben or ‘ongoing life’.63

The view of the work and its translations being presented here does not reduce the significance of the text that Brontë wrote, nor scant her genius in writing it. Rather, it offers a better description of the complex mode of existence of a literary work, and of how translations relate to it, than does the still-widespread, ‘common-sense’ conception, which we saw embodied in the Berne Convention (as well as in Ewbank’s essay), where what is in fact just one reading of the source text is reified as ‘the original’ (‘our Jane Eyre’) and translations are expected to reproduce it. Academic studies of literary translation nowadays rarely assert this view explicitly, but it still pervades the practice and language of critical discussion: for instance, the introduction to a recent, large study, Milton in Translation, presents its chapters as bringing to light ‘the keenness on translators’ parts to offer as faithful a rendition as they see possible’, as aiming at ‘feasible degrees of equivalence’, as singling out ‘aural effects … that are lost in translation’ and as assessing ‘translational infelicities’.64 As Lawrence Venuti has been tireless in pointing out,65 such attitudes are widespread elsewhere in academia and in literary and media culture. But if you keep hold of the fact that ‘there is no “work itself,” only a set of signs and a conjunction of reading practices’, as the Canadian poet and translator Erín Moure has said,66 then you can allow yourself to recognize — with Parfit’s help — that these signs and practices continue, via a series of links, into the different-though-related signs and practices of the translations, and the reading of them, and the other translations that will arise. When it is seen like this, we can assert, with Antonio Lavieri, that:

La traduzione acquista una nuova legittimità, mostrando l’inesistenza di un significato transcendentale, resistendo all’ideologia della trasparenza della scrittura, della lingua e del traduttore, diventando oggetto di consocenza che, interrogandosi, interroga e trasforma il senso.67

[Translation acquires a new legitimacy, demonstrating the non-existence of a transcendental signified, resisting the ideology of the transparency of writing, of language and of the translator, and becoming an object of knowledge which, questioning itself, questions and transforms the meaning.]

And we can realize, with Henri Meschonnic, that both the work and its translations consist of a perpetual and mutually generating ‘mouvement’ [movement], so that ‘les transformations d’une traduction à l’autre d’un même texte’ [the transformations from one translation to another of the same text] are ‘à la fois transformations de la traduction et transformations du texte’ [at the same time transformations of the translation and transformations of the text].68 Each translation is an instance of this larger movement by which the work, the world Jane Eyre, is constituted.

The translations that I have discussed so far question and transform Jane Eyre in various ways. They ask what matters more and matters less in the plot, as shown by the cuts made by Zhou Shoujuan and Old Nick, translating with different generic commitments for the benefit of their disparate readerships in different cultures and times. They reveal elements of ideological distinctiveness and challenge, as with the varying excisions made in the Soviet Union and Portugal under Salazar. They give a view of the directness of Jane’s style, as it would come through to the ‘mothers and girls’ targeted by the ‘Agreeable Library’ in Milan in 1904. And there is the particular emotional and dramatic contour from ‘leaving’ to ‘not leaving’ that Old Nick creates with verbal repetition in the aftermath of the fire in Mr Rochester’s bedroom. Such transformations show us something about prevailing reading practices in the cultural moments when they occurred, as well as about the individual sensibilities of the translators who created them. And they change Jane Eyre itself. Taking inspiration from Parfit, we can talk of both physical (textual) elements and reader experiences that turn out to have either greater or lesser persistence in the ongoing life of the work; and we can see how new elements and experiences can emerge from earlier ones without destroying Jane Eyre’s identity. Such changes matter also to the work as it inhabited its first contexts of composition and reception. Those contexts are often assumed to be monocultural and monolingual; but, as we have seen, the novel was being read in Germany, the Netherlands, Belgium, France, Russia, Denmark, Chile, Cuba, Bolivia and Sweden — as well as North America and no doubt elsewhere — in the three years after it came out in London; the review that Brontë most liked was in French; and, as I will explain in Chapter II, Brontë’s own linguistic repertoire included French, German and Yorkshire languages (or, as I prefer to say, modes of languaging): it is not quite right to say that Jane Eyre was first written ‘in English’. Even if we take the most restricted possible conception of interpretive context — what the Brontë family themselves might have made of the novel as they sat at home in the parsonage at Haworth — it is not possible to say with certainty that any transformation through translation makes visible something that was not already in Jane Eyre for them, as it was first transformed in their own imaginations as they read it.

The same is true at the level of verbal detail. This will be evident in many of the essays that follow, and will be the focus of my discussion in Chapters IV–VII; but here is a small example. Near the start of the novel, the young Jane has been attacked by her cousin John Reed, and has fought back against him. He has ‘bellowed out loud’ and Mrs Reed has arrived with the servants Bessie and Abbott. The fighting children are parted, and Jane hears the words:

‘Dear! dear! What a fury to fly at Master John!’

‘Did ever anybody see such a picture of passion!’

The phrase ‘picture of passion’ feels as though it might be proverbial; but the Literature Online database suggests that it may have appeared only once in English-language literature before this moment.69 In context, it sounds like a colloquial idiom, more likely to be uttered by Abbott or Bessie than by Mrs Reed. And indeed Mrs Reed chimes in next, in her commanding tones: ‘“Take her away to the red-room, and lock her in there.”’ If we focus on ‘a picture of passion’, as uttered in Bessie’s or Abbott’s voice, what image do we think it conjures? What do we see and hear? Is the tone sharply disapproving? — or might it include a touch of warmth towards the child? — or even of wonder? How is Jane being viewed? — as understandably emotional? — or incomprehensibly aggressive? We can air such varying possibilities, and different readers might incline to one more than the others; but translations give us a visible spectrum of views. Here are some of them:

He1986 ראיתם פעם תמונה משולהבת כזאת [{ra’item pa’am temuna meshulhevet ka-zot} Did you ever see such an ecstatic picture?]

It1974 Si è mai vista una scena così pietosa? [Have you ever seen such a pitiful scene?]

F1964 semblable image de la passion! [similar image of passion!]

Sp1941 ¡Con cuánta rabia! [With so much rage!]

Por1951 Se já se viu uma coisa destas!… É uma ferazinha! [Have you ever seen a thing such as this one?… She’s a little beast!]

R1950 Этакая злоба у девочки! [{Ėtakaia zloba u devochki} What malice that child has!]

F1946 pareille image de la colère [such an image of anger]

Por1941 Onde é que já se viu um monstro destes?! [Have you ever seen a monster such as this one?]

F1919 pareille forcenée [such a mad person / a fury]

R1901 Видѣлъ-ли кто-нибудь подобное бѣшенное созданіе! [{Vidiel li kto-nibud’ podobnoe bieshennoye sozdaníe} Has anyone seen such a furious (lit. driven by rabies) creature!]

Did ever anybody see such a picture of passion!

R1849 Кто бы могъ вообразить такую страшную картину! Она готова была растерзать и задушить бѣднаго мальчика! [{Kto by mog voobrazit’ takuiu strashnuiu kartinu! Ona gotova byla rasterzat’ i zadushit’ biednago ma’’chika} Who could have imagined such a terrible sight/picture! She was ready to tear the poor boy apart and strangle him!]

It1904 Avete mai visto una rabbiosa come questa? [Have you ever seen a girl as angry as this one?]

Por1926 Já viu alguem tal accesso de loucura! [Has anyone ever seen such a madness fit?]

He1946 ?הראה אדם מעולם התפרצות כגון זו [{hera’e adam me-olam hitpartsut kegon zo} Has anyone ever seen an outburst like that one?]

Sp1947 ¿Habráse visto nunca semejante furia? [Have you ever seen such fury?]

It1951 Non s’è mai vista tanta prepotenza! [I’ve never seen such impertinence]

Sl1955 jeza [fury]

Sl1970 ihta [stubbornness]

A1985 هل قدر لأي امرئ أن يرى مثل هذا الانفعال من قبل؟ [{hal quddira li ayy imriʾ an yarā mithla hadha al infiʿāl} Was anyone ever destined to see such a reaction]70

This moment will be discussed in more detail in Chapter IV below, where you will also be able to watch the translations and back-translations unfolding as an animation. Of course, the back-translations do not exactly reproduce the translations they represent, any more than the translations themselves exactly reproduce Brontë’s text. But they do serve to give an impression of the imaginative suggestiveness of the phrase (as we will see in Chapters IV–VII, very many phrases in the novel are suggestive in a similar way). We might say that what we are seeing here is a snapshot of the different linguistic and cultural circumstances in which the translations were made — and, certainly, any one of these quotations could be subjected to a discrete critical analysis to elucidate its significances in its immediate contexts. But this word cloud also shows us what we might call the potential of the source text — all those meanings which, as Sakai has explained, we cannot know are in the text until after they have been articulated by translation. Word upon word, each translator changes Brontë’s text by saying what it is for them.

As we scan the array of translations, we are inevitably struck by the differences between languages. This, after all, is why the translations have had to be made. But we can also notice continuities: ‘rabbiosa’ in Italian and ‘rabia’ in Spanish; ‘passion’ in English and ‘passion’ in French. Indeed, given the substantial presence of French in Jane Eyre, which I will explore in Chapter II, I am not even sure that ‘passion’, as Brontë wrote it, should be defined as an English word. As we watch the novel being remade across language difference via translation it becomes clear that a view of languages as internally homogeneous and separate from one another, with translation operating between these distinct entities, is inadequate for understanding the phenomenon before us. Prismatic Jane Eyre enjoins a refreshed understanding of language difference and of how it relates to translation — an understanding that we will pursue in Chapter II.

Works Cited

For the translations of Jane Eyre referred to, please see the List of Translations at the end of this book.

Adam, Jean-Michel, Souvent textes varient. Génétique, intertextualité, édition et traduction (Paris: Classiques Garnier, 2018).

The Autobiography of Jane Eyre, https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCG1-X6Vhx5Ba84pqBQUDshQ

The Autobiography of Jane Eyre, https://www.tumblr.com/blog/view/eyrequotes

Barthes, Roland, ‘The Death of the Author’, Aspen: The Magazine in a Box, 5&6 (1967), n.p., https://www.ubu.com/aspen/aspen5and6/threeEssays.html#barthes