The General Map https://digitalkoine.github.io/je_prismatic_generalmap/ Created by Giovanni Pietro Vitali; © OpenStreetMap contributors

The World Maphttps://digitalkoine.github.io/je_prismatic_map Created by Giovanni Pietro Vitali; maps © Thunderforest, data © OpenStreetMap contributors

III. Locating the Translations

© 2023 Matthew Reynolds, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0319.08

‘Locating’, here, has layered and intermingled senses.1 There is tracking down any given translation now, in a database, library catalogue or bookshop. There is situating its first appearance and its circulation geographically, as on a map. There is placing it in time. And then there is the whole intricate and finally unanswerable question of how to locate a translation vis à vis everything it is ‘into’: not just ‘a language’, but a particular linguistic idiom and style, in a cultural context (or better, as we will see, a complex of contexts), with some kind of purpose, among expectations, in conversation with other texts, in, or in connection to, a genre. The pages that you have read so far have already raised these issues in abundance, and the essays that immediately follow this chapter focus on them with special intensity. So this chapter serves as a hinge, aiming to open general issues of location, and explore them across several languages and contexts before the essays to come zoom in on more particular places.

In this endeavour, I will ask you, from time to time, to open one or other of the interactive maps, built by Giovanni Pietro Vitali, to which these pages are linked. Our use of maps has drawn inspiration from the work of Franco Moretti, and we agree with him that it is important to ‘make the connection between geography and literature explicit’.2 However, learning from Karima Laachir, Sara Marzagora and Francesca Orsini, we have also been wary of the process of abstraction that is inevitably involved in cartography, and of the detached, synoptic and thin kind of knowledge that a map therefore tends to provide. In harmony with those scholars, we hope that our discussion shows ‘sensitivity to the richness and plurality of spatial imaginings that animate texts, authors, and publics in the world’.3 As we have already begun to see, the ‘world’ that is inhabited by the world work Jane Eyre is not some featureless international zone — not a world of airports — but a network of particular locations, each thickly striated and complicatedly entangled, with variable degrees of connection between them. It is a world unevenly patched together from a collection of ‘significant geographies’, to adopt Laachir, Marzagora and Orsini’s term. Places that are distant in space may be closely linked in the history of Jane Eyre translation, as with the connection from Brussels and Paris to Havana, Santiago de Chile and La Paz which we discovered in Chapter I. Or the same city may, both in relation to Jane Eyre and in other ways, be split from itself by a historical event, like Tehran before and after the Islamic Revolution, as we will see in Essay 8 by Kayvan Tahmasebian and Rebecca Ruth Gould. We have tried to bring something of this awareness of complexity into the maps themselves, in two ways. First, by making them interactive, so that you can zoom in on any given point and click for more information about it; and second, by providing several different kinds of map, each offering a distinct view, so that the ensemble enables varied kinds of perception to emerge. We hope to generate an understanding of the significant geographies of Jane Eyre translation from the interplay between the varied modes of representation, and different critical voices, that are brought together in these pages. The mobile visuals of the maps are in dialogue with the broad interpretive arguments in the chapters, such as this one; and also with the more tightly focused analyses in the essays.

The Point of a Point on a Map

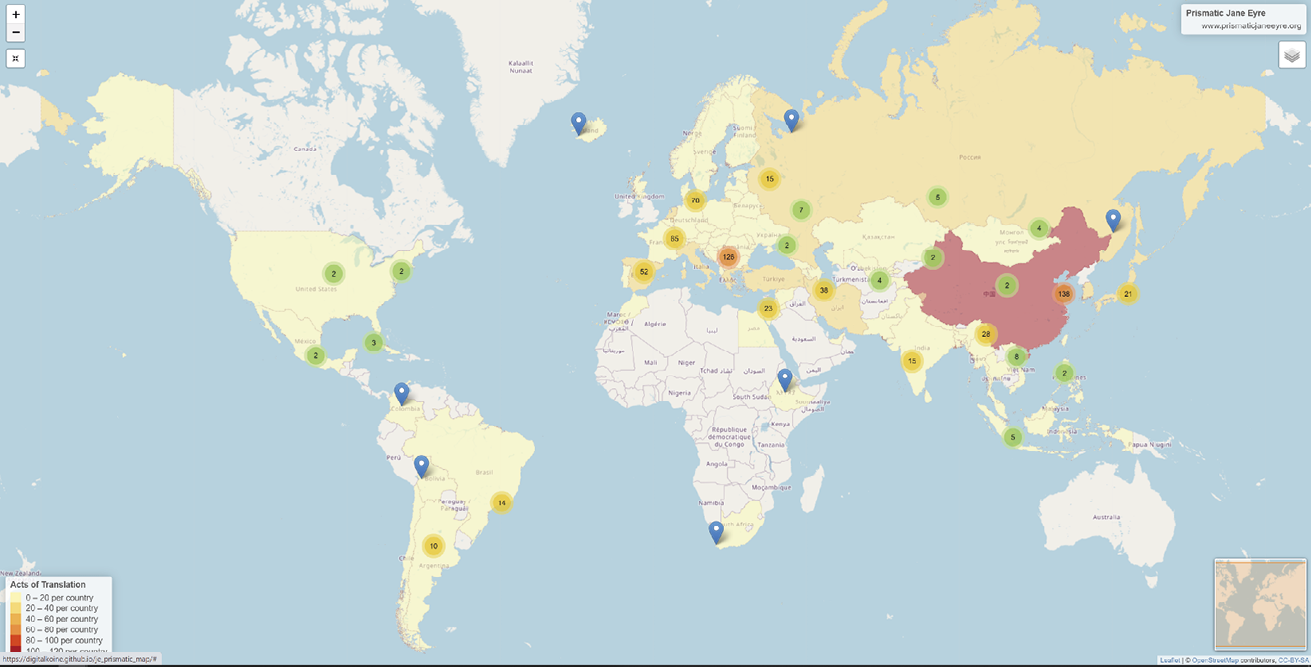

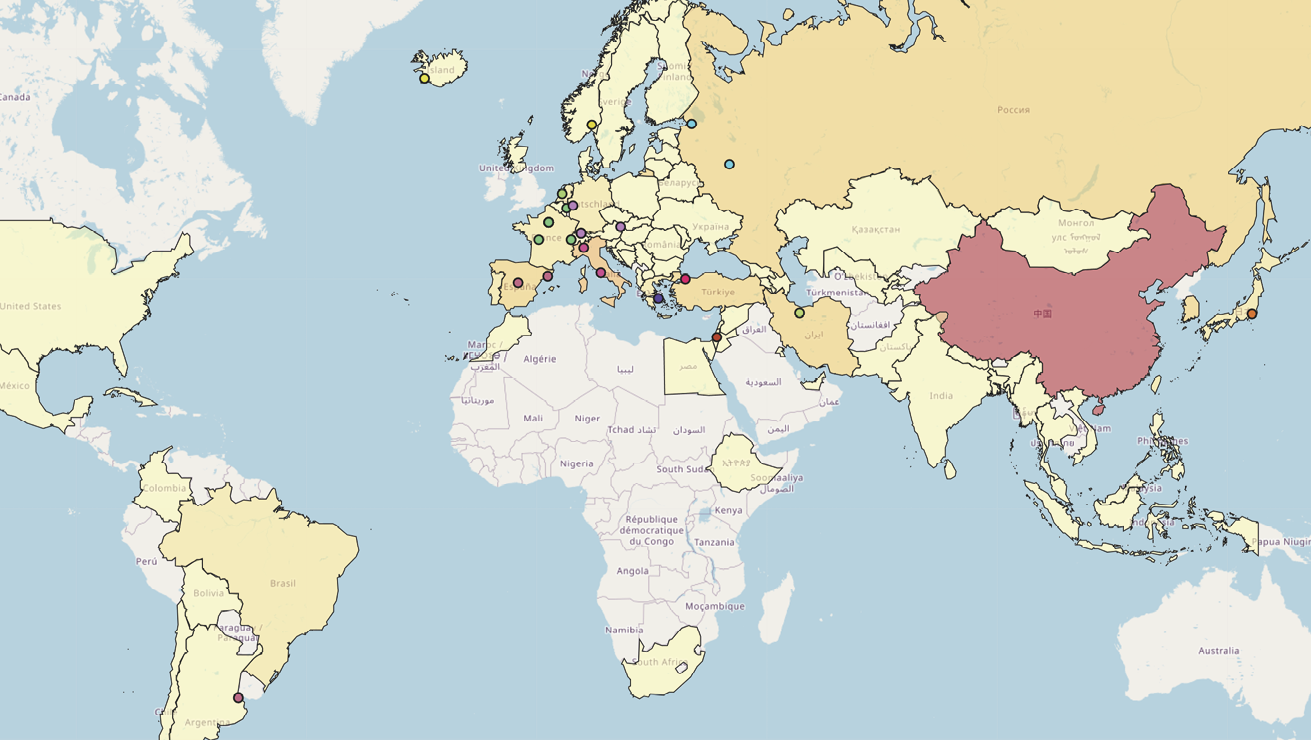

Fig. 7 The General Map, zoomed out to provide a snapshot of the global distribution of Jane Eyre translations. Created by Giovanni Pietro Vitali; © OpenStreetMap contributors

Each little circle represents what we call an ‘act of translation’ — that is, either the first appearance of a new translation, or the re-publication of that translation in a new place (I will expand on this definition below).4 The darker the circle, the more recent the act of translation. The impression we get is very imperfect, for many earlier acts of translation are hidden by later ones; but still, looking at the map, we can immediately see the very broad spread of Jane Eyre translations. No longer is this a novel that was begun in Manchester and written mainly in Haworth, Yorkshire, in Charlotte Brontë’s distinctive language(s). Rather, it has been — and is still being — written in many hundreds of locations, with as many different linguistic repertoires.5 We can also register the uneven distribution of the translations, the thick crowds in Europe, China, Japan, Korea and Iran, for instance; and the patchier scattering in the Americas. Here is a first visual indication of the world of Jane Eyre translation as a mesh of significant geographies. Finally, there are the large tracts of the world where no translations have appeared. These include places where one would not expect them to, such as Greenland, together with countries where they perhaps might have done, such as Côte d’Ivoire, Venezuela or Peru. They also include, of course, countries where English is a — or the — dominant language, such as Australia, Ghana, Nigeria, Canada, and England itself (the United States does not figure in this group because translations have appeared there, into Russian, Vietnamese and Spanish, and neither does Scotland, because of recent translations into North-East Scots, Cornish and West Frisian published there by Evertype). In Essay 1 we discovered, with Ulrich Timme Kragh and Abhishek Jain, the effect on Jane Eyre translations in India of the widespread use of English in that country, as well as of colonial and post-colonial education structures; and in Essay 7, below, Annmarie Drury explores related reasons that explain, and give significance to, the paucity of Jane Eyre translations in sub-Saharan Africa: different significant geographies are revealed by these detailed examinations. Nevertheless, reflecting on this aspect of the map as a whole, what is striking is the negative it gives to what one might naively think to be the global distribution of English literature, as happening primarily in ‘English-speaking countries’. Though we have not attempted the impossible task of tracking the circulation of English-language copies of Jane Eyre, it is the case that they might be found anywhere: from the first year of the novel’s existence, when a cheap English edition was published in Leipzig by Tauchnitz, the book has travelled widely, and many people with English as an additional language have read the text that Brontë wrote.6 Even more important is the obvious, though neglected, fact that is made starkly visible by our map: it is in countries where English is not a primary language that Jane Eyre has been most translated — that is, where it has generated the particular, intense imaginative life that goes into making a translation, and attracted the distinctive sorts of attention that go into reading one (though of course these vary in different cultures and times). There is a kind of energy in an ongoing life through translations that a continuing existence in a source language does not have.

If you now open the General Map and zoom in wherever you like, you will see that the little circles representing each act of translation are located in cities and towns (and the occasional village). We have not attempted to show the spread of each translation’s readership, because that cannot be known. Equally we have not tried to visualise the geographical reach of the language that each translation might be thought to be ‘into’. There are two, interrelated reasons for this, which I have already touched upon in Chapter I. Languages, conceived as entities that are internally consistent and separate from one another, are brisk abstractions from actual linguistic usage which is always complex and changeable, with boundaries — if they exist at all — that are fuzzy and shifting.7 The account of Jane Eyre in Arabic, or Arabics, given by Yousif M. Qasmiyeh in Essay 3 above is a case in point. And translations are never merely into ‘a language’, but are made with a particular linguistic repertoire, in a given context and moment, with aims in view and stylistic preferences in play. Neither a translation’s mode of relating to language(s), nor the mode of existence of language(s) in the world, can adequately be represented on a map.

Another entity a translation might be thought to be ‘into’ is the ongoing literary culture of a nation-state. Here again the picture is complicated, for nation-states are of course political constructions, and their borders, though more distinct than those of languages, can also change, and radically so. Indeed, the State in which a translation was done may now no longer exist: the former Yugoslavia and former USSR are obvious examples. Nevertheless, the hope of contributing to the growth of a national culture can be an important driver of translation, as Andrés Claro will outline for the Latin American context in Essay 5 below; and successive translations in the same publishing market can be in dialogue or competition with one another, as we have begun to see in the case of France in Essay 4 by Céline Sabiron, and as many of the essays to come will also reveal. So our maps do show the borders of States, together with the number of acts of translation that have happened within them, though with the proviso that the borders indicated are those that hold at present (or rather, that held at a moment in the twenty-teens when the ground-maps that we have employed were created) — so the State in which a translation was published may not be the same as the State within whose boundaries it now appears. The maps, then, need to be read with an awareness of the historical shifts which their presentist representation of borders conceals. In the General Map, as you can see, the different States where acts of translation have occurred are all indiscriminately coloured green, giving the impression of a continuity of activity across them. However, in another map, the World Map, we have taken a different approach, and coloured them differently according to the number of acts of translation that each has hosted. This makes the difference between the States look more substantial, and provides a rough contour diagram of the intensity of translation activity in different places.

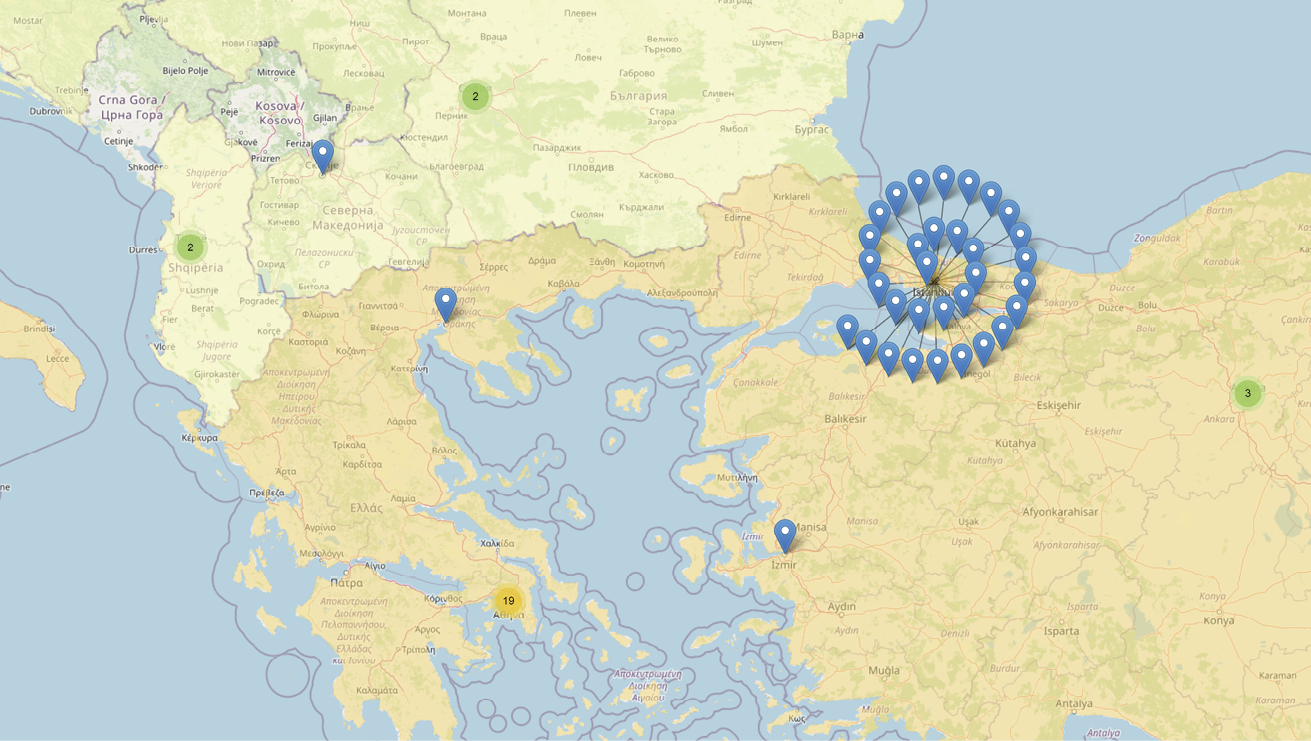

So one thing that mapping helps us to understand is, paradoxically, how much about the spatial distribution of translations we cannot represent, or indeed know; as well as how much we can know and represent only very imperfectly. But what the maps do show clearly, as Giovanni Pietro Vitali pointed out while we were making them, is the importance of cities as centres for the publication of translations (as they are for the publication of books in general). The World Map, though it gives a less immediate impression of the world-wide spread of Jane Eyre than the General Map, is a better tool for exploring the phenomenon of the city because it groups the translations numerically. For instance, Figure 8 presents the World Map zoomed in to show the distribution of Jane Eyre translations in Turkey, Greece, Albania, North Macedonia and Bulgaria: you can see that Istanbul and Athens are very prominent sources, with lesser contributions emerging from Ankara, Izmir, Thessaloniki, Sofia, Tirana and Skopje.

Fig. 8 The World Map zoomed in to show the distribution of Jane Eyre translations in Turkey, Greece, Albania, North Macedonia and Bulgaria. Created by Giovanni Pietro Vitali; maps © Thunderforest, data © OpenStreetMap contributors

If you move around in the World Map you will find that this pattern, with acts of translation being concentrated in a capital city, is fairly common. In South Korea, all 27 acts of translation into Korean occurred in Seoul; in Japan, all 22 took place in Tokyo except for one (Kyoto, 2002); in Iran, 26 translations into Persian have been published in Tehran, and 1 each in Mashad, Qom and Tabriz. In Europe, you sometimes find a similar distribution: Greece, 19 acts of translation in Athens and 1 in Thessaloniki (1979), as we can see in Figure 2; France, 18 in Paris and 1 in Poitiers (1948). But there are also more dispersed environments. Of Italy’s 39 acts of translation, 19 occurred in Milan, but the rest are shared out among 12 other places. German has a yet flatter configuration which spreads across Germany and beyond: 7 in Berlin; 3 for Stuttgart; 2 each for Leipzig and Frankfurt; 1 each for six other German locations; and then 6 in Zurich, 2 in Vienna and 1 each in Klagenfurt and Budapest.8 The markets, the distribution networks, and the socio-political dynamics are different in each case; and so therefore are the reach and significance of each act of translation.

Seeing translations emerge physically into the world in this way brings the work of translation and the business of publication close together. Both are needed for Jane Eyre, or any text, to find readers in new language(s) in another place. This is why, for the purposes of our maps, we chose to define an ‘act of translation’ in the way I have described — as either the first appearance of a new translation, or the re-publication of that translation in a new place — and to create a separate entry for each such act (we have identified 683 of them in total). The result is that, when you look at our maps, translation’s activity of making Jane Eyre available in a spread of new locations comes to the fore. In particular, two striking instances of such migratory re-publication are made visible.

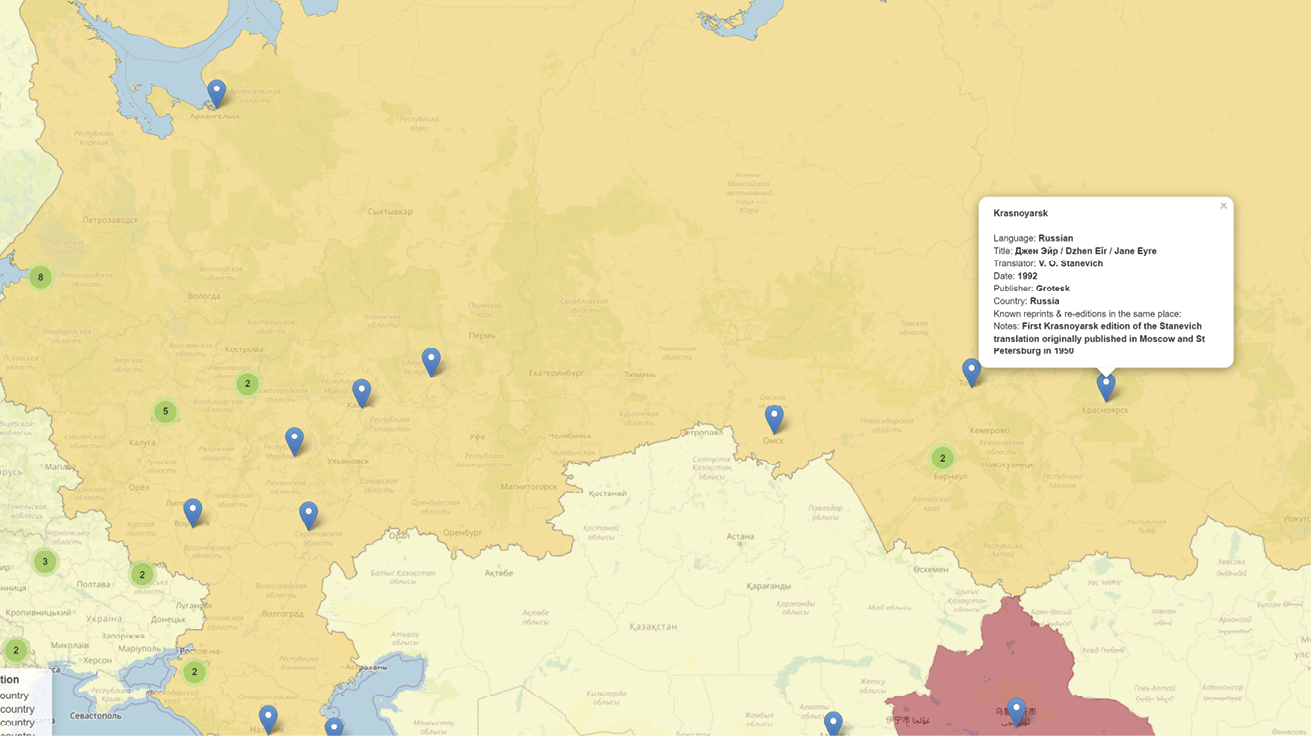

The first, researched by Eugenia Kelbert and Karolina Gurevich, is the case of a classic translation of Jane Eyre into Russian by V. O. Stanevich. This text was first published simultaneously in Moscow and Leningrad in 1950. It was much reprinted in both those cities; but its geographical publication-life also extended a great deal further. On our maps, you can watch it appearing in Alma-Ata, in what is now Kazakhstan, and Kiev, in Ukraine (1956), Minsk, in modern Belarus, Barnaul, in Altai Krai, and Gorkji, now Nizhny Novgorod (1958), Tashkent, in what is now Uzbekhistan (1959); and then Krasnodar, on the Eastern edge of the Black Sea (1985), Makhachkala on the Caspian Sea (1986), Saransk, in Mordovia (1989), Baku, in Azerbaijan (1989), Voronezh (1990), Izhevsk, in the Urals (1991), Krasnoyarsk, in Siberia (1992 — see Figure 12), Omsk, again in Siberia (1992), Kalinigrad on the Baltic (1993), Kazan, on the Volga (1993), Tomsk (1993), Ulan-Ude, in the Russian Far East (1994), and Nal’chik, in the Caucasus Mountains (1997).

Fig. 9 The World Map, zoomed in to show the 1992 publication of Stanevich’s Russian translation in Krasnoyarsk, Siberia. Created by Giovanni Pietro Vitali; maps © Thunderforest, data © OpenStreetMap contributors

This distribution gives us a window onto the conditions of publication, first of all during the 1950s and then during the period of Glasnost and the dissolution of the USSR. The very fact that these successive publications in different locations were necessary shows that the first acts of translation in Moscow and Leningrad did not translate the novel ‘into Russian’, in the sense of making it available to all Russian speakers, nor ‘into the USSR’ or ‘into Soviet culture’, in the sense of conveying it to all inhabitants of that state or participants in that culture. The first acts of translation brought the novel to smaller linguistic, topographical and cultural areas (that is, significant geographies); and more acts of translation were needed to carry it further.

The second instance is the vivid and absorbing translation of Jane Eyre into Spanish by Juan González-Blanco de Luaces, first published in Barcelona in 1943. As Andrés Claro will describe in Essay 5, Luaces, a republican, had had a career as a novelist before the establishment of Franco’s regime, and turned to translation both to make a living and as a way of continuing the imaginative life that was no longer available to him as an author. His version of Jane Eyre was much reprinted in Barcelona; it then crossed the Atlantic to Argentina where it appeared in Buenos Aires in 1954, joining four other Jane Eyre translations that had been published there during the 1940s. Claro explains how the significance of the act of translation changed in the new context: the same text that, in Barcelona, had enabled Luaces to ‘write between the lines’ in resistance to Franco became, when transplanted to Buenos Aires, ‘part of an explicit programme of opening up to and interacting with foreign languages and literatures as a way of creating a local ethos and literature emancipated from Spanish colonialism’, taking on particular significance because ‘the novel became widely known at the very time the female vote and other civil rights for women were being secured’. It was only after this that Luaces’s translation came out in Madrid, where Claro notes that the literary scene was more Francoist than in Barcelona: it was first published there in 1967, by the same transnational firm, Espasa-Calpe, that had brought it to Buenos Aires. Reprints continued (and still do) in all these cities; and in 1985 Luaces’s translation appeared in a second South American location, Bogotá, from a different publisher, Oveja Negra. Tracking this text shows us an instance of the transnational dynamics of Spanish-language publishing, and the varying pressures that have encouraged translation in different locations and times.

All these cases reveal the productive interplay between, on the one hand, the pressure to visualise which comes from trying to make a map and, on the other, the resistance to being visualised which comes from the complex nature of the linguistic and cultural locations that translations are actually in. Maps make blatantly obvious what we cannot know: we cannot put boundaries around a language, and we cannot trace where translations travelled or were read. But we can see where they were published, and reflecting on that single parameter can — in dialogue with more detailed knowledge — open onto an understanding of the significant geographies that they inhabited. To move through such geographies is also to advance through time; and we have tried to capture something of this phenomenon in our Time Map.

Translation in Time

The Time Map, created by Giovanni Pietro Vitali and Simone Landucci, should be tranquilly running through history when you open it (if it isn’t, click the ‘play’ button at the bottom left). Note that each dot representing an act of translation lasts for six years, before disappearing: this is to help the map be legible, but it also hints at the temporal life of a translation which, though it may be reprinted, become a classic, or indeed simply be stumbled across, picked up and read at any time, nevertheless tends on the whole to have a brief moment of higher visibility in culture, followed by a long stretch of comparative obscurity. If you wish to freeze time in a particular year, you will see that there is a ‘pause’ button at the bottom left that enables you to do so.

When we watch the ongoing, proliferative pulse of the world-novel Jane Eyre in this map, what do we see? In Atlas of the European Novel (1998), Franco Moretti offered a pattern that we too might discover. Focusing on Europe, and generalising initially from the case of Don Quixote, he suggests that the diffusion of translations tends to happen in three ‘waves’: first, nearby literary cultures (which he calls ‘core’), then a pause; then somewhat further afield (‘semi-periphery’); and after that more distant cultures — the ‘periphery’.9 The approach builds on Itamar Even Zohar’s polysystem theory, and adopts its tripartite structure from Immanuel Wallerstein’s theorization of ‘The Modern World-System’, in which ‘core’ economies accomplish tasks that require ‘a high level of skill’, the periphery provides ‘“raw” labour power’, and the semi-periphery contributes ‘vital skills that are often politically unpopular’.10 It is not immediately obvious why this particular economic model should apply to literary writing: as Johan Heilbron has pointed out, ‘the world-system of translation … does not quite correspond to the predominant view in world-systems theory … Cultural exchanges have a dynamic of their own’.11 We might also demur at the implicitly low valuation that this picture of waves emanating from a centre gives to the skill and creativity inherent in translation, and to the imaginative energies of the translating cultures — factors that are abundantly evident throughout the essays and chapters that you are reading. Still, there is also something attractive about the metaphor of translation as a wave spreading through many locations, in that it seems as though it might, to some extent, register the proliferative dynamics that we began to explore in Chapter I, with Old Nick’s version prompting others which then prompted others again. So how far does the translation history of Jane Eyre conform to this possible blueprint of three waves?

Well, the novel was translated into cultures well-connected to English in the three years after its first publication in 1847: Germany, France, Belgium, Russia, the Netherlands, Denmark and Sweden. It is plausible to see this group of countries as closely linked both culturally and economically — as forming a multilingual and transnational significant geography — a ‘core’ in Moretti’s terms. But, as we discovered in Chapter I, these are not the only places where Jane Eyre was translated in those early years. During 1850–51 it appeared in South America and the Caribbean, first in Santiago de Chile, where it was serialized in the newspaper El Progreso, then Havana, in another newspaper, Diario de la Marina, then elsewhere in Cuba (Matanzas) and Bolivia (La Paz). As we saw, the mediate source for these texts was Old Nick’s French version, first published in the French newspaper Le National and the Brussels-based Revue de Paris and L’Indépendance belge, which had been put into Spanish for the Correo de Ultramar in Paris, an act of translation that was designed to travel to Spanish-speaking locations overseas. The detour via French helped Jane Eyre to be catapulted across the Atlantic, for the Caribbean and South American publications drew their cultural material primarily from France as well as Spain, with only the very occasional bit of English. In El Progresso, the novel serialised immediately after Juana Eyre was Edward Bulwer-Lytton’s Leila; or, The Siege of Granada (1838), but that — as its title suggests — is an English novel with a strong Spanish connection; the other texts appearing in the preceding and following months were translations of two novels by Alexandre Dumas, and an account of the 1847 murder of Fanny, duchesse de Praslin ‘traducida del francés’ [‘translated from French’].12 Likewise, in Diario de la Marina, books serialized in the years before and after Jane Eyre included Fédéric Soulié’s Les Drames inconnus, Alexandre de Lavergne’s La Circassienne, José María de Goizueta’s Leyendas vascongadas, Antonio Flores’s Fé, esperanza y caridad, and multiple novels by Dumas: Le Comte de Monte-Cristo, Les Quarante-cinq and Le Vicomte de Bragelonne.13 The international news coverage in both papers tended to have a similar geographical orientation. So in this leap of Jane Eyre across the Atlantic we can see a particular set of connections enabling an act of translation that does not fit the model of a generalized wave.

Fig. 10 Time Map: translations 1848–53. Created by Giovanni Pietro Vitali and Simone Landucci. © OpenStreetMap contributors, © Mapbox

After this early rush, there was something of a slowdown. If we confine our attention to Europe, we might take this to show that a group of cultures more immediately connected to English should be distinguished from a spread of those that were somewhat more detached — or, on Moretti’s schema, first from second ‘waves’. Despite the substantial exception presented by the Chilean, Cuban and Bolivian Juana Eyres, the model does retain some explanatory power. After 1850 there was a second translation into French, in 1854 (this time published in Paris) as we saw in Chapter I, and re-translations also in German, Swedish and Russian between 1855 and 1857. The first translation into a new language, however, was not until 1865, into Polish, serialized in the Warsaw magazine Tygodnik Mód (Fashion Weekly).14 It was followed by the first Hungarian translation in 1873, then Czech in 1875 and Portuguese in 1877 (an incomplete version serialised in a Lisbon magazine). Perhaps here we can discern another pause, before first translations then happen in Japan (1896 — albeit an incomplete version), Norway (1902), Italy (1904), Armenia (1908), Finland (1915), Brazil (c. 1916), China (1925), Romania (1930), into Esperanto in 1931 (in the Netherlands), Ukraine (1939), Argentina (1941), Brazil and Turkey (1945), Mandatory Palestine, into Hebrew (1946), Iceland (1948), Greece (1949), Iran (1950), India, into Tamil (1953), Burma (1953), Slovenia and Bulgaria (1955), Sri Lanka, into Sinhalese (1955), Lithuania (1957), Estonia (1959), Korea and Vietnam (1963), Serbia (1965), Croatia (1974), Latvia (1976), Bangladesh, into Bengali (1977), Malaysia (1979), Ethiopia, into Amharic (1981); India, into Punjabi (1981); India, into Malayalam (1983), North Macedonia (1984), the Philippines, into Tagalog (1985), Spain, into Catalan (1992); India, into Gujarati (1993), Nepal (1993), Thailand (1993), Spain, into Basque (1998), India, into Assamese (1999), India, into Hindi (2002), Albania (2003), South Africa, into Afrikaans (2005), Tajikistan (2010), China, into Tibetan (2011), Mongolia (2014), India, into Kannada (2014), and Scotland, into Doric Scots (2018).

As we look at this broad, complicated scattering of first translations, the idea that it can be organised into three waves that correspond to ‘core’, ‘semi-peripheral’ and ‘peripheral’ cultural and economic status, comes to pieces, and with it the assumption that the agency involved is predominantly an emanation from a cultural centre, with Jane Eyre being passively received in all these locations like a delivery of international aid. Is Bolivia ‘core’ while Hungary is ‘semi-peripheral’? Is Italy ‘peripheral’ while Sweden is ‘core’? Clearly more varied and particular forces are at work — and several of them are detailed in the essays that follow this chapter. In at least one case, an endeavour conducted from England, to disseminate English culture, is indeed a decisive element. As Eleni Philippou will explain in Essay 6, the first Greek translation came about in 1949 as part of a programme of soft power in the context of the Cold War. But, in many other instances, the energies that most drive acts of translation originate in the locations which we should no longer think of, in the habitual terms of Translation Studies, as ‘target’ or ‘receiving’ cultures, but rather as ingurgitating cultures, along the lines of the Latin American anthropophagous manifestoes penned by Haroldo de Campos and Osvaldo de Andrade, and mentioned by Andrés Claro in Essay 5. As Claro shows, translations such as M. E. Antonini’s, published in Buenos Aires by Acme Agency in 1941, should be seen, not as being subjected to ‘the foreign’ but rather as choosing to ‘journey through’ it. Likewise, in Iran after the Islamic Revolution — as Kayvan Tahmasebian and Rebecca Ruth Gould will explain in Essay 8 — translators turned to Jane Eyre to answer specific imaginative needs. In this vein of interpretation, an absence of Jane Eyre translations, as in many sub-Saharan African countries, need not be configured as a lack, since it can also be a sign of resistance or sufficiency: of there being no desire to translate Jane Eyre because interests are directed elsewhere. As soon as you begin to register the complexity of each situation in which translation is (or is not) happening, and of the dynamics that drive it, the broad-brush geometry of a single core and generalised periphery comes to seem more a matter of imperialistic assumption than of observation or reading. A better description would recognise that there are many cores, with energies sparking in multiple directions.15

Seeing this can help us to understand why the proliferative life of the world work Jane Eyre does not only happen via the first translation into any given language. It is not that, once translated, Jane Eyre has simply arrived. Rather, a first translation can open onto a phase of intense imaginative engagement conducted through re-translations which are in dialogue with one another as well as with Brontë’s text. Tahmasebian and Gould illuminate one such phenomenon, the 28 new translations into Persian since 1982. Another, startling instance consists of the 108 new translations into Chinese since 1990 (see Figure 11).

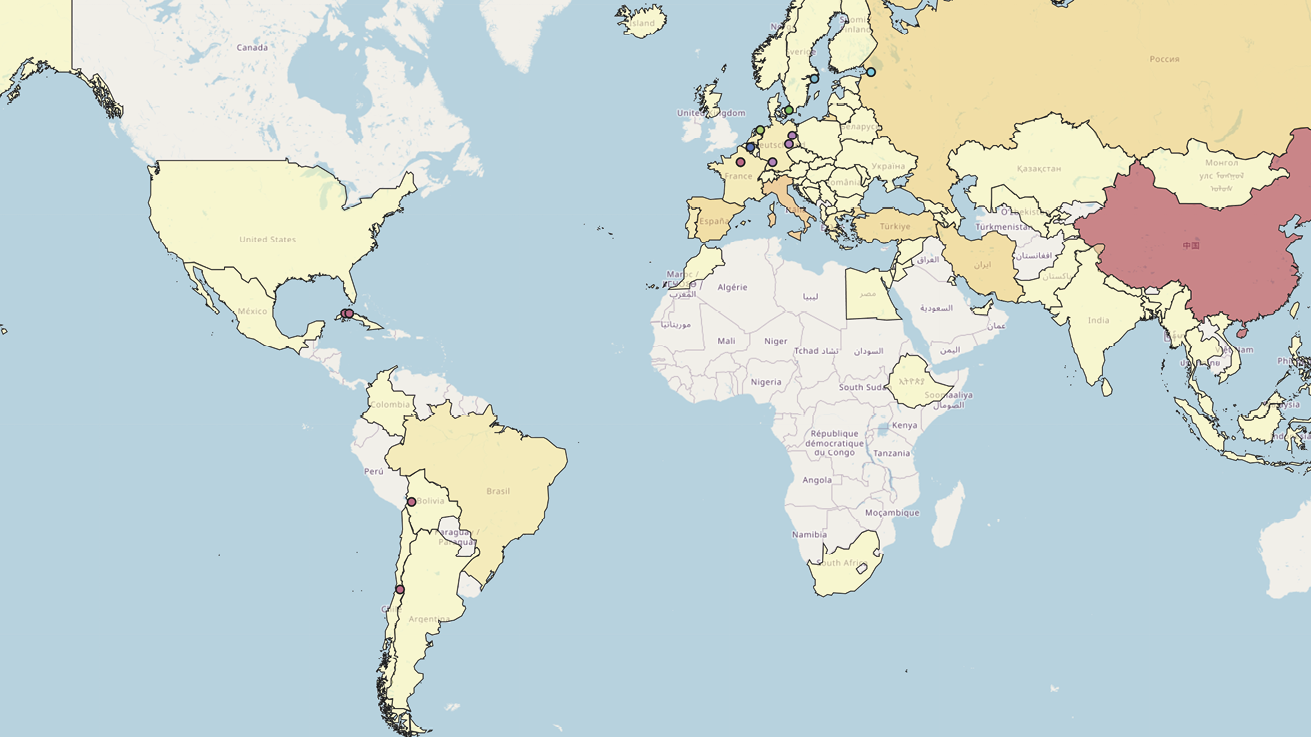

Fig. 11 The Time Map, zoomed in to show intense Jane Eyre translation activity in China, South Korea, Taiwan and Nepal, 1992–97. Created by Giovanni Pietro Vitali and Simone Landucci. © OpenStreetMap contributors, © Mapbox

No doubt there is some reiteration of material between these multitudinous publications, though we have not been able to establish how much. Nevertheless, it remains the case that, during the last three decades, Jane Eyre has been more voluminously re-written and reprinted in China than anywhere else. Once you start paying attention to re-translations there are other distributions of energy that emerge. During the 1980s there were 8 new translations into Korean but none into French or German. Where shall we say the ‘core’ of Jane Eyre translation is located at such times? Similar phases of intensity can spread across national boundaries. For instance, there was a surge of Jane Eyre translation, concentrated in Europe, at the end of the Second World War (see Figure 12), with 25 new translations being published between 1945 and 1948: 8 each into French and Spanish, 3 into German, 2 into Turkish, and 1 each into Dutch, Italian, Norwegian and Hebrew (written by the Paris-based modernist artist Hana Ben Dov, and published in Jerusalem in 1945). The post-war prestige of English can be seen here, abetted by the glamour of the widely distributed 1943 American film, directed by Robert Stevenson and starring Orson Welles and Joan Fontaine. Significance can be found also in a longer, narrower dispersion, such as the 39 translations into Italian since 1904: they have followed one another at intervals which, though decreasing recently, have remained comparatively regular across the twelve decades. Jane Eyre in Italy has been a continuing presence that publishers and translators have found reason to turn to, to re-angle or re-juvenate, from time to time.

Fig. 12 Time Map: translations 1945–50. Created by Giovanni Pietro Vitali and Simone Landucci. © OpenStreetMap contributors, © Mapbox

Looking at the Time Map, and indeed the World and General maps, in dialogue with the detailed analyses conducted in the essays, helps us to see that each translation of Jane Eyre involves a mix of sources of agency. Translation is not a passive reception but an active engagement. To be sure, elements of cultural domination or encroachment are in play: the power of English, growing globally throughout the period of Jane Eyre translations so far, is a crucial factor in the way they have spread. But also in play is the agency of translators, publishers, readers, and other elements in the ingurgitating culture. There is the choice to translate, the recognition of why the book might be needed or liked, the power to cut large stretches of it (as we saw in Chapter I), the labour of re-making the work with different linguistic materials, re-orienting it with an eye to the new market and in collaboration with the translator’s imaginative disposition and style. Each culture where this happens is not merely peripheral to a centre that lies elsewhere: it is in many respects a centre to itself. Seeing this brings us back to the idea of the world as a network or patchwork of significant geographies. But what kind of significance are we talking about?

Locational Textures

By significant geographies, Laachir, Marzagora and Orsini mean ‘the conceptual, imaginative, and real geographies that texts, authors, and language communities inhabit, produce, and reach, which typically extend outwards without (ever?) having a truly global reach’.16 In the case of translation, all three of these geographies are doubled — or more than doubled — because there are always at least two points of view from which each of them can be projected. On the one hand, there are the material (‘real’) factors that have enabled the novel to travel from its first publication in London, perhaps through the medium of other languages and re-imaginings, to the place where it is being translated. On the other, from the point of view of the ingurgitating culture, there are the material factors that have enabled it to be sourced, brought in, translated and distributed. On the one hand, the ‘conceptual’ frame that starts from London and that tends to see the world work Jane Eyre in terms of spread; on the other, the conceptual frame that starts from the place of translation, and which is likely to be built from other elements, including perhaps emulation, but also interest, choice or a perception of need. And then there is the ‘imaginative’ geography that has been generated in collaboration with the text — a shifting landscape that has been variously inhabited by Charlotte Brontë, many millions of readers in English(es) and other language(s), and many hundreds of translators. This imaginative geography is affected by the other two kinds: what you see in the novel will be influenced by where you are standing, and the frame through which you are looking. But it can also permeate them in its turn, altering their significance and shape. The world that is in Jane Eyre is changed by and also changes the world that it is in.

The Jane Eyre that Brontë wrote is a novel full of significant migrations. From her unhappy childhood home, Gateshead Hall, Jane is sent fifty miles away to Lowood School, a whole day’s journeying which seems, to the ten-year-old girl who is travelling alone, much longer: ‘I only know that the day seemed to me of a preternatural length, and that we appeared to travel over hundreds of miles of road’.17 Eight years later Jane moves again, to Thornfield Hall: this means another long spell of coach-travel as Thornfield is situated in a ‘shire’ that was ‘seventy miles nearer London than the remote county where I now resided’ — though the older Jane is now better able to cope with the journey.18 After many months at Thornfield she makes a visit back to Gateshead to see Mrs Reed on her deathbed: this is ‘a hundred miles’ each way.19 Then, six weeks or so later, after the failed wedding, she flees Thornfield, getting on a coach that is travelling to ‘a place a long way off’, though she only has twenty shillings instead of the thirty-shilling fare; she is therefore set down before the coach reaches its destination, at a place called ‘Whitcross’, in a ‘north-midland shire’, ‘dusk with moorland, ridged with mountain’: it is ‘two days’ since she left Thornfield.20 She wanders the landscape, spends two nights in the open, walks ‘a long time’, and ends up at Moor House, also known as Marsh End. From there, after some weeks, she moves a little way to the village of Morton when she becomes a schoolteacher. After some months, just before Christmas, and after she has come into her surprise inheritance, she moves back to Moor House; from there, on the ‘first of June’ she returns to Thornfield, a journey of ‘six-and-thirty hours’, followed, when she has found Thornfield in ruins, by another ‘thirty miles’ to Ferndean.

If we try to plot these distances against some of the real places thought to have inspired Jane Eyre’s five key locations (as gathered by Christine Alexander in The Oxford Companion to the Brontës), we can find a shadow of resemblance, albeit a somewhat truncated one. If we located Gateshead not far from Stonegappe, the house in Lothersdale, near Skipton, where Brontë was unhappy as a governess, then it would be a bit more than forty miles north-west from there to the site of the Clergy Daughters’ School at Cowan Bridge, the inspiration for Lowood. If we sited Thornfield near Rydings, the battlemented home of Charlotte’s friend Ellen Nussey, in Birstall Smithies, just outside Leeds, then that would be about fifty-five miles back to the south-east. If we followed Ernest Raymond and equated Whitcross with Lascar Cross on the Hallam Moors, in the Peak District outside Sheffield, then that would be about forty miles south of our site for Thornfield. Finally, from Thornfield it is thirty miles to Ferndean; and so it is also from Rydings to Wycoller Hall, the ruined house that may have helped Ferndean to be imagined. Wycoller is also only ten miles from the Brontës’ home at Haworth: perhaps Brontë liked to think of Jane ending up nearby.

Obviously these equations are very approximate. The imagined places are not the real ones, and even their names dislodge them from any actual geography, locating them in a gently symbolic landscape of gates, woods, thorns, a marsh, a moor and a cross. Nevertheless, looking at a map of England does give us a sense of the kind of span that is crossed in the novel. It makes sense to pin Lowood to Cowan Bridge, in the North-West, near the Lancashire coast, since that episode is so tightly rooted in the harrowing facts that Brontë lived through at the Clergy Daughters’ School. And Whitcross and Moor House must be somewhere in the Peak District, in the North Midlands, given the topography as well as the likely equation of ‘S—’ (mentioned in Chapter 31) with Sheffield. Between these two extremities, which are in fact only a hundred miles apart, we could amuse ourselves by sliding the other locations around on the map, to try to make the distances between them match up. Or, better, we could realise that the journeyings in the novel are simply longer, more expansive, than those that Brontë herself took between the loosely equivalent actual English places. Jane Eyre does not inhabit a realist geography, but a more malleable kind of imaginative landscape. The novel’s major locations, encountered in sequence, are also stages of life: early childhood; school; adulthood and romance; despair and an alternative future; back to the ruins of romance and a more secure, because damaged, living-on of the relationship. Various textualities flow into these locations, shaping them and giving them significance. There is the textuality of Brontë’s life, as we have begun to see. Part of the reason why Thornfield is so far from everywhere is that the emotional experience Brontë is most channelling in these pages took place further away still, in Brussels: her exhilarating, heartbreaking attachment to her married French teacher M. Heger. This is also why there is so much French spoken at Thornfield. There are also literary models, of course. Most prominent among them are John Bunyan’s The Pilgrim’s Progress, with its Christian journey through a series of allegorical locations (including a gate, a ‘slough’ — or marsh — and several houses); Jonathan Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels (which the young Jane likes to read), in which the protagonist journeys from one anthropologically instructive fantasy location to another, each imagined as a different country; the Arabian Nights (also read by the young Jane), with its succession of different stories and settings, all linked in the person of the spellbinding woman narrator; and Dickens’s Oliver Twist, in which the protagonist (a young boy) makes a long journey to London where he encounters two possible homes and associated family-style attachments — one disreputable, the other genteel — and moves back and forth between them.

So far, we have seen the significant geography imagined in the novel blending elements from realistic topography, biographical experience and literary analogues. These factors all contribute to Jane Eyre’s distinctive, and unusually complex, generic makeup, with its blend of precise observation, fierce personal feeling and occasionally fantastical narrative developments. But there is also another dimension to the world within the book, one which it shares with other nineteenth-century British novels such as Austen’s Mansfield Park, Thackeray’s Vanity Fair or Dickens’s Great Expectations. This is created by the connections drawn between locations that are book’s focal points and places elsewhere — in Europe and especially in the British Empire — which are all, in various ways, brought home to the English setting. The presence of Adèle at Thornfield Hall is the first prominent instance of this dynamic. Whatever her biological relationship to Mr Rochester, she is there as witness to his dissolute time in Paris, itself (as we later learn) only part of a decade-long, Don Juan-esque romp around Europe.21 As a figure, Adèle is a kind of prelude to the revelation of Bertha Rochester’s presence in the house: both the girl and the woman have been brought there from elsewhere, and are — as Rochester sees it — left-overs from rejected phases of his life. But Bertha is, of course, from further away — from Spanish Town, Jamaica — and is much more fiercely rejected than Adèle, both by Mr Rochester and by the narrator. If the girl is a channel for Francophobia, Bertha is charged with the racist attitudes, and fear and guilt about Empire, which I discussed in Chapter I. St John Rivers, with his evangelizing mission somewhere in India, is another kind of embodiment of those attitudes, and another textual manifestation of fear and guilt. Where Bertha is said to be ‘incapable of being led to anything higher’, St John is presented as labouring on behalf of people subject to the ‘informal’ Indian empire of that period, clearing ‘their painful way to improvement’.22 The novel does not wholly support his endeavour (after all, Jane chooses a different path), but it does not wholly condemn it either (St John writes the book’s last words). These two conflicting figures, Bertha and St John, who take contrasting journeys to and from virtually opposite points on the globe — Jamaica and India — show the strange, profoundly uneasy and yet also merely gestural way in which Jane Eyre sees locations in England as being intimately joined to places elsewhere in the world. As Susan Meyer has pointed out, the fact that Jane’s inheritance comes from an uncle who is a wine-merchant in Madeira, that is, someone who is embedded in imperial structures of trade, leaves her with wealth from a troubled source, just like the money that came to Mr Rochester from Bertha’s family, the Masons. In fact, this uncle, John Eyre, is the first of all the emissaries of Empire in the book, turning up, as Mrs Reed’s maid Bessie tells the story in Chapter 10, to look for Jane at Gateshead just a year or so after she had moved to Lowood. The account is brief, and seems inconsequential, so the connection may not strike a reader as significant until its consequences play out much later in the novel. But its uncanny intimacy with Jane, and indeed eery joining of Jane and Bertha, is suggested right from the start by the phonetic play around the location of John Eyre’s business: Mad-eira. Of course many other flickers of suggestiveness have been noticed in Jane’s surname: ‘air’, ‘ire’, even ‘Eire’ in the sense of Ireland. Nevertheless, it is striking that the other dominant surnames in the novel attach characters physically to a landscape, in the same vein as the names of the houses: Rivers, Reed, Roch(rock)ester, Burns, even Temple. But Eyre floats weirdly free, and can attach itself, not only to Madeira but to that ‘eyrie’ in the ‘Andes’ which — as we saw in Chapter I — is called to mind, much later on in the novel, by Bertha’s cry. So this fourth, world-spanning dimension of the significant geography imagined in the book cuts across the others, opening yawning spatial voids and throwing sudden bridges across them.

How does this complicated envisaging of location within the novel matter to the translations? In several ways, one of which occurs when there is a conjunction between a translator’s geographical situation and a place imagined in the novel. Ulrich Timme Kragh and Abhishek Jain, in Essay 1, have already explored how writers, film-makes and translators in India have responded, in their re-makings of the novel, to the role of India within it. Another example will appear in Essay 5, by Andrés Claro, with its analysis of the reactions of Spanish-speaking translators in South America to the representations of Bertha Rochester and of Spanish Town, Jamaica. A further consideration is how the English place-names are, or are not, translated. Studying European Portuguese translations, Ana Teresa Marques dos Santos has noted a consistent practice of reproducing the English names, rather than attempting to render their significance. This means that their gentle symbolism is pushed into the background (though of course some readers of Portuguese translations will also have sufficient knowledge of English and be able to register it); and instead ‘Thornfield’, ‘Rivers’ and the rest become insistent reminders of the book’s primary location in England.23 This kind of change alters location and genre together, shifting the book a bit more in the direction of documentary realism.

Genre is the clearest bridge between location in the book and the location of the book. How places are imagined is a key part of the novel’s generic identity; and the novel’s identity affects where it sits in the culture it is published into, and how readers relate to it. Book covers signal genre and often they do so by choosing to represent particular scenes and locations from the novel. Our last set of maps, the Covers Maps, enables you to explore this phenomenon in conjunction with the locations where the books were published.

These maps are necessarily partial: often we were not able to source cover images; and the covers of most of the earlier translations were of course unrevealingly plain. Nevertheless, working with these maps, we can discern international trends: favourite images for Jane Eyre covers are a solitary woman (often the 1850 George Richmond pencil portrait of Brontë); a solitary woman reading or writing; a romantic couple; a young woman with a big house in the distance; the house burning; and many variants of Jane’s first encounter with Rochester when he falls from his horse. Both the house and the landscape are sometimes plausibly English and sometimes not. We can observe the global influence of film versions and BBC adaptations, which bring with them their own visualisations: a cover inspired by the 1943 Robert Stevenson film with Orson Welles appears in Buenos Aires in 1944; the 1996 Zeffirelli version prompts covers in Paris (1996), Sâo Paolo (1996) and Istanbul (2007); and the 2006 BBC series with Ruth Wilson and Toby Stephens leaves its mark again in Istanbul (2009), as well as in Colombo (2015) and Giza (2016). And we can also discern national trends: Germany has a long-standing preference for the solitary woman, while the romance scenes prominent on the covers of Persian translations announce a significant shifting of the book into the genre of romance, as part of its re-location in Persian literary culture: Kayvan Tahmasebian and Rebecca Ruth Gould explore this development in Essay 8.

Partial as they are, the Covers Maps help one to shift perspective from the global view of our other maps, and register the look of the individual books, and thereby sense something of the market conditions in which they were produced and the presence of the people involved in the design and production process. Of the translators themselves, generally very little is known. About eighty of them are anonymous and, of the others, it is only in rare cases such as Marion Gilbert (French), Juan González-Blanco de Luaces (Spanish), Munīr’ al-Baʿalbakī (Arabic) and Yu JongHo [유 종호] (Korean) that more than the barest details are recoverable — as you can discover from the selected brief biographies provided in the appendix, Lives of Some Translators, below.

Likewise, much detail about the cultural location of translations — where they are being read, and the uses to which they are being put — is necessarily unknowable. For instance, it is only by chance, and thanks to the mediating work of Sowon S. Park, that I came to know of Seo SangHoon, who works at Reigate Grammar School Vietnam in Hanoi, and who uses Jane Eyre, in the Korean translations by Ju JongHo and Park JungSook, to teach students about narrative voice and, as he says, ‘why we should accept information around us critically’.24 There are innumerable other instances of the enterprise of Jane Eyre translation finding distinct significance in particular locations. Some of the most striking are gathered in the sequence of essays that follows this chapter. Andrés Claro traces differences between the Spanish translations published in Spain and in Latin America, focusing especially on issues of gender, race and empire (like Essay 1, this essay is necessarily long, given the wide range of material considered). Eleni Philippou shows how the British Council supported the translation of Jane Eyre in Greece as part of an exertion of soft power during the Cold War. Annmarie Drury explores the complex of reasons behind the lack of Jane Eyre translations into Swahili and most other African languages both during the period of the British Empire and after. And Kayvan Tahmasebian and Rebecca Ruth Gould uncover the intricate relationship between Jane Eyre and ideas of romance in twentieth-century Iran, which accounts for the surprising surge in translations that followed the 1979 revolution.

Works Cited

For the translations of Jane Eyre referred to, please see the List of Translations at the end of this book.

Diario de la Marina (Habana: s.n., 1850–51).

Ethnologue, https://www.ethnologue.com/about/language-maps

Heilbron, Johan, ‘Towards a Sociology of Translation: Book Translations as a Cultural World-System’, European Journal of Social Theory, 2, 4 (1999) 429–44.

Kalifa, Dominique and Marie-Ève Thérenty, ‘Introduction’, https://www.medias19.org/publications/les-mysteres-urbains-au-xixe-siecle-circulations-transferts-appropriations/introduction

Laachir, Karima, Sara Marzagora and Francesca Orsini, ‘Significant Geographies: In Lieu of World Literature’, Journal of World Literature, 3.3 (2018), 290–310, https://doi.org/10.1163/24056480-00303005

Franco Moretti, Atlas of the European Novel, 1800–1900 (London and New York: Verso, 1998).

El Progreso (Santiago de Chile: Imprenta del Progreso, 7th February – 4th April, 1850).

Reynolds, Matthew and Giovanni Pietro Vitali, ‘Mapping and Reading a World of Translations’, Digital Modern Languages Open, 1 (2021), http://doi.org/10.3828/mlo.v0i0.375

Wallerstein, Immanuel Maurice, The Modern World System, 4 vols (Berkeley, University of California Press, 2011).

1 An earlier treatment of some of the material in this chapter was published as Matthew Reynolds and Giovanni Pietro Vitali, ‘Mapping and Reading a World of Translations’, Digital Modern Languages Open, 1 (2021).

2 Franco Moretti, Atlas of the European Novel, 1800–1900 (London and New York: Verso, 1998), p. 3.

3 Karima Laachir, Sara Marzagora and Francesca Orsini, ‘Significant Geographies: In Lieu of World Literature’, Journal of World Literature, 3, 3 (2018), 290–310 (p. 293).

4 I am grateful to Eugenia Kelbert for suggesting the phrase ‘an act of translation’.

5 See Chapter I above for an account of Brontë’s language(s) and an explanation of ‘repertoire’.

6 For French readers of the early English-language Tauchnitz editions, see Essay 4 above, by Céline Sabiron.

7 At first sight, the expensively commercialized language maps produced by Ethnologue appear to give an impressive rendition of the intricacy of language borders and borderlands. But the approximation inherent in these visualisations is evident from the description of their data sources and processes given here: https://www.ethnologue.com/methodology

8 These translations listed in this paragraph were researched by Emrah Serdan, Sowon S. Park, Kayvan Tahmasebian, Yorimitsu Hashimoto, Eleni Philippou, Céline Sabiron, Léa Rychen, Vincent Thierry, Alessandro Grilli, Caterina Cappelli, Anna Ferrari, Paola Gaudio, and Mary Frank.

9 Moretti, Atlas, p. 171.

10 Wallerstein, Immanuel Maurice, The Modern World System, 4 vols (Berkeley, University of California Press, 2011), vol. 1, p. 350.

11 Johan Heilbron, ‘Towards a Sociology of Translation: Book Translations as a Cultural World-System’, European Journal of Social Theory, 2, 4 (1999), 429–44.

12 El Progreso, 1 November 1849 – 18 June 1851.

13 Diario de la Marina, 18 January 1848 – 12 December 1851.

14 We are grateful to the book collector Jay Dillon for alerting us to this 1865 translation.

15 Somewhat similarly, the Mystères urbains au XIXe siècle project identifies three centres ‘qui vont chacun autonomiser leur série de mystères urbains: les Etats-Unis, la Grande Bretagne et la France’ [‘each of which establishes its own series of urban mysteries: the United States, Great Britain and France’], Dominique Kalifa and Marie-Ève Thérenty, ‘Introduction’, https://www.medias19.org/publications/les-mysteres-urbains-au-xixe-siecle-circulations-transferts-appropriations/introduction

16 Laachir, Marzagor and Orsini, ‘Significant Geographies’, p. 294.

17 JE, Ch. 5.

18 JE, Ch. 10.

19 JE, Ch. 21.

20 JE., Chs 27 and 28.

21 JE, Ch. 27.

22 JE, Chs 27 and 38.

23 Marques dos Santos presented these findings as part of her collaboration in the Prismatic Jane Eyre project.

24 Seo SangHoon, email to the author, 09.13, 20 March 2020. Quoted with permission.