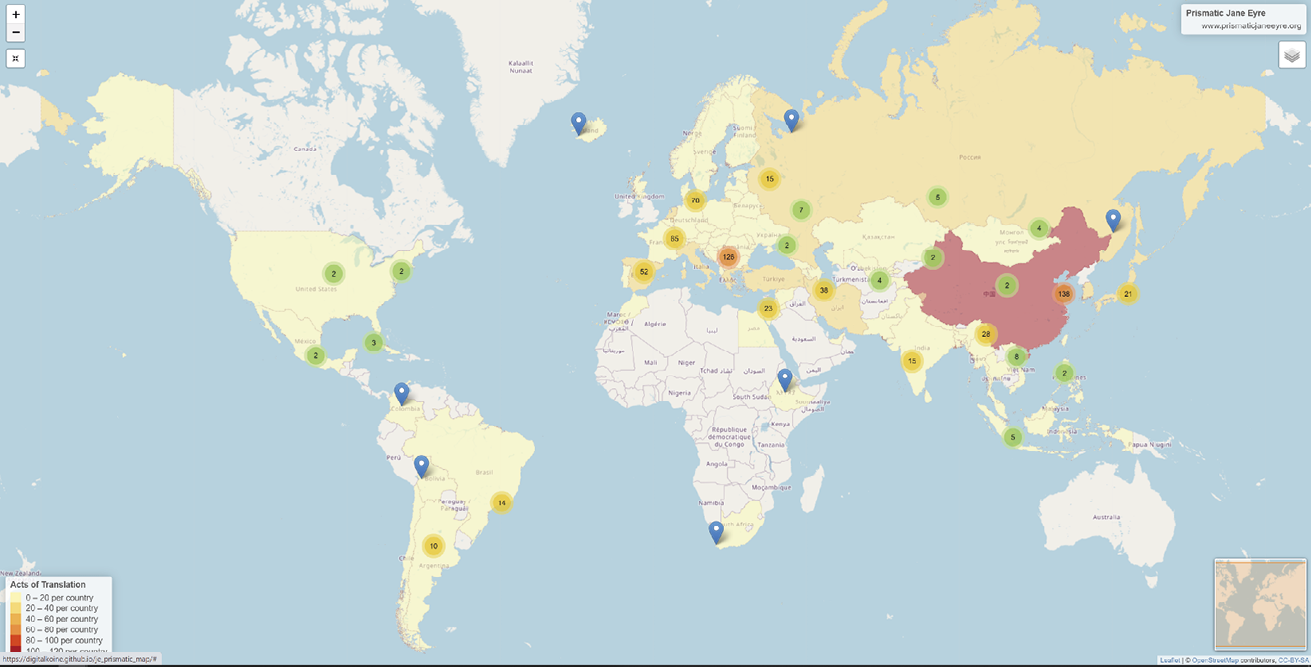

The World Map https://digitalkoine.github.io/je_prismatic_map Created by Giovanni Pietro Vitali; maps © Thunderforest, data © OpenStreetMap contributors

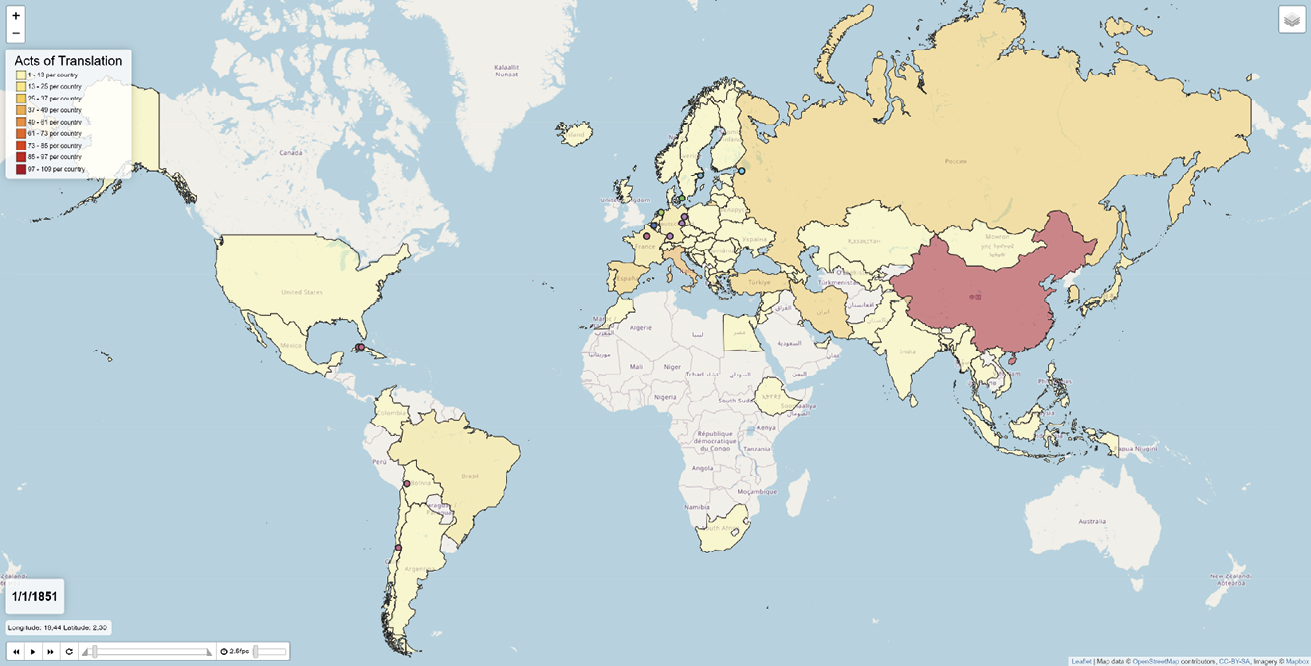

The Time Map https://digitalkoine.github.io/translations_timemap Created by Giovanni Pietro Vitali and Simone Landucci;© OpenStreetMap contributors, © Mapbox

IV Close-Reading the Multiplicitous Text Through Language(s)

© 2023 Matthew Reynolds, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0319.13

What Sort of Close Reading?

As will be more than clear by now, the phenomenon that we are reading — the world Jane Eyre — is vast and varied. It crosses time, geography and language(s). Its internal organization is both complex and fluid, because, as I argued in Chapter I, and as is evident in several of the essays you will have encountered so far, it is not possible to draw a firm distinction between one instance of this world work and another — that is, between one text, in whatever language, and the next. You can never be certain whether something that is made explicit in one text is not implicit in another, nor whether something visibly left out in a later version has not been quietly skipped, forgotten or felt to be superfluous by readers of other versions before. To read several instances of Jane Eyre together is, therefore, not a matter of comparing fixed entities but rather of opening up the textuality of each through its intermingling with the others. Hence the ambiguity in the title of this chapter. The text that Brontë wrote is already ‘multiplicitous’, and it passes ‘through language(s)’ to generate others (translations, and translations of translations); so, to read them is also to read it. And the whole of the world Jane Eyre is an (even more) multiplicitous text, which can be read through the language(s) with which it is composed. This chapter, and the chapters that follow, offer close readings of this plural text, this transtemporal, migratory and multilingual phenomenon, focusing on the transformations of key words.

So this chapter, and Chapters V–VII, bring many threads, from many kinds of languaging, together. In so doing, they provide a centre of gravity, or point of reference, for the many other modes of close reading exhibited in this publication. This volume gathers the work of individuals, and both reading and the writing-from-reading that generates ‘a reading’ are, though taught and shareable, finally individual practices: each participant has their own style. As you will have discovered, what the essays present is not the result of a determinate method applied equally to all the varied texts and locations, translations in India treated in the same way as translations in Greece, and so on. Rather, in the course of the project that has given rise to this volume, shared interests and tactics emerged through conversations in which all the participants joined. The essays were then written from that intellectual context, with each writer pursuing the lines that seemed most interesting to them in dialogue with the wider, collaborative endeavour. This arrangement recognises that Laachir, Marzagora and Orsini’s concept of ‘significant geography’ (which I described in Chapter III) applies not only to the people and texts under discussion but also to the people and texts who are doing the discussing. Each of us enters the phenomenon of the world Jane Eyre from a different place, with different points of reference, and can only grasp some areas of it, even while being aware of the other areas explored by our colleagues.1 Close-reading a world text requires collaboration; and collaboration generates a plurality of readings, from different perspectives and in different modes.

There is some kind of closeness in all the analyses throughout this book. The discussions of contexts of Jane Eyre translation in the essays placed earlier in the volume (for instance Essay 1 by Ulrich Timme Kragh and Abhishek Jain on India, Essay 5 by Andrés Claro on Spain and South America, Essay 6 by Eleni Philippou on Greece, or Essay 8 by Kayvan Tahmasebian and Rebecca Gould on Iran), pay close attention to the detail of those contexts, connecting them to features of the translation-texts. In the terms of the early C21st debates about formalist modes of reading in the United States academy, we could say, with Susan J. Wolfson and Marjorie Levinson, that these are instances of ‘activist new formalism’, that is, of interpretations that recognise the inherence of the literary text in larger textualities of history and ideology.2 The same recognition runs throughout the volume, even when historical contexts are not explicitly brought into consideration. This is why the essays are not divided into different sections but are rather presented as a sequence, punctuated by orientatory chapters such as this one. The essays introduced by Chapters I and II may have particular relevance to the conceptualisation of translation, and those introduced by Chapter III may give special attention to place, but close reading permeates them all.

The essays and chapters that come next, forming roughly the second half of the book, are, correspondingly, those that focus most tightly on textual and formal aspects of the world Jane Eyre, while also being aware of its contexts. In Chapter V, I explore a selection of instances of the word ‘passion’ in the novel, presenting a synoptic view of how they are transformed in many languages, moments and locations. In Essay 9, Ana Teresa Marques dos Santos and Cláudia Pazos-Alonso study the ‘volcanic vehemence’ of Jane’s self-expression as it comes through in a selection of translations from Portugal and Brazil, paying particular attention to what happens to the word ‘mind’. In Essay 10, Ida Klitgård explores, in a similar vein, what becomes of the word ‘passion’ in Danish. A broader, quantitative approach is then taken by Paola Gaudio in Essay 11: she tracks what happens to all the nouns expressing feeling in the novel, with the aim of gauging how its overall emotional climate may be different in Italian.

Chapter VI then studies instances of the word ‘plain’ as they are re-made in many languages — a case which, as we will see, is revealingly different from that of ‘passion’. This is followed by Essay 12, in which Yunte Huang explores proper nouns and pronouns in Chinese, starting from the coincidence that the name ‘Jane Eyre’ can be rendered with the characters ‘简爱’ [jian ai] which also mean ‘simple love’: this only-partially-appropriate compound has become the book’s dominant title and has strongly affected its reception in China. Mary Frank, in Essay 13, turns to consider an aspect of grammar, the need for German translators to decide whether characters refer to one another with an intimate or formal kind of ‘you’ — ‘du’ or ‘Sie’ — and, in particular, whether Jane and Rochester ever call each other ‘du’. Here, attention to the translations opens onto a consideration of the dynamics of intimacy in Brontë’s text, including Mr Rochester’s use of the diminutive ‘Janet’. In Essay 14 Léa Rychen considers the prominence of references to the Bible, and in particular to its 1611 Authorized (or ‘King James’) Version, asking what becomes of this significant strand of intertextuality in French, where there is no equivalent canonical Bible to quote.

Chapter VII offers a fresh synoptic view, via a consideration of the spiritually inflected terms ‘walk’ and ‘wander’, again tracing their shifts of significance and connotation across several tongues; it also presents two ‘prismatic scenes’, and concludes with a theorisation of ‘littoral reading’. In Essay 15, Jernej Habjan focuses on a peculiarity of the style of Jane Eyre — its use of free indirect speech in quotation marks, that is, in the way direct speech is more usually presented. He shows German and Slovenian translators working out how to handle this conundrum, and from there develops a new understanding of the representation of speech in the text that Brontë wrote. In the last two essays in the volume, exploration of the source text and of the translations proceeds as a single, dialogic movement. Madli Kütt, in Essay 16, conducts a comparative investigation of first-person presence across the English and Estonian texts, given that ‘Estonian has a large variety of means to avoid direct reference to either the speaker or the listener’, tending ‘to focus instead on the event, possession or experience itself’. Reading this most intensely first-person of novels in Estonian, therefore, means discovering ‘new, altered points of view’. Finally, in Essay 17, Eugenia Kelbert asks an apparently simple question: what do the characters look like? From an investigation of six Russian translations, in dialogue with Brontë’s text, she proposes that the world Jane Eyre creates ‘a multiplicity of imagined persons across the globe’. In Chapter VIII, I offer some conclusions to this rich series of readings, and to the volume as a whole.

All these instances of close reading, diverse though they are, have at least one feature in common. They do not conceive of what they are investigating as an object which can be isolated from other textualities. This, then, is not close reading in the tradition of the New Criticism, where what is being read, usually a poem, has to be configured (in the words of Cleanth Brooks) as a ‘unity’ so as to discover how it organizes ‘apparently contradictory and conflicting elements of experience … into a new pattern’.3 Rather, the close readings gathered here enter into a textual environment that has no end: they cultivate some patches of it, but maintain an awareness of the unexamined tracts of the world Jane Eyre that lie beyond. In this, they owe more to the Roland Barthes of S/Z, who insisted that:

Si l’on veut rester attentif au pluriel d’un texte … il faut bien renoncer a structurer ce texte par grandes masses, comme le faisaient la rhétorique classsique et l’explicitation scolaire … tout signifie sans cesse, et plusieurs fois, mais sans délégation à un grand ensemble final, à une structure dernière.

[If we wish to remain attentive to the plural of a text … we must give up structuring the text into large masses, in the vein of classical rhetoric and scholarly explication … everything signifies ceaselessly, in several ways, but without having to be referred to a great, final unity, to an ultimate structure].4

And they follow the traces of Julia Kristeva, who, in the course of her theorization of intertextuality, saw any given text as a ‘productivité’ [productivity], born from ‘plusieurs pratiques sémiotiques’ [several semiotic practices] which are ‘translinguistiques, c’est à dire faites à travers la langue et irréductibles aux categories qui lui sont, de nos jours, assignées’ [translinguistic, that is to say, they happen across language and are irreducible to the categories imposed on language these days].5

Despite her own deeply multilingual repertoire, Kristeva did not pursue her concept of the ‘translinguistic’ into instances of translation: in this respect, Prismatic Jane Eyre is taking a road that was opened but left untravelled by her work. Likewise, Barthes does not offer any explicit discussion of translation. Yet S/Z is, just like this volume, an intense close reading of a single piece of prose fiction which, at times, Barthes describes in terms that also fit Prismatic Jane Eyre:

Le texte unique n’est pas accès (inductif) à un Modèle, mais entrée d’un réseau à mille entrées; suivre cette entrée, c’est viser au loin, non une structure légale de normes et d’écarts, une Loi narrative ou poétique, mais une perspective (de bribes, de voix venues d’autres textes, d’autres codes), dont cependant le point de fuite est sans cesse reporté, mystérieusement ouvert.6

[The single text does not give (inductive) access to a Model, but is rather the entrance to a network with a thousand entrances; to take this entrance is to set one’s sights, in the distance, not on a legal structure of norms and gaps, a narrative or poetic Law, but a perspective (of crumbs, of voices come from other texts, of other codes) whose vanishing point, however, is ceaselessly pushed back, mysteriously open].

Barthes here is describing how study of a single text can show us something about all literature, making a poststructuralist argument which, when it is confined to the homolingual interpretive environment of Standard French (or indeed Standard English), has to do ceaseless battle against the constraining forces of publishing conventions and interpretive norms. However, when it is applied to the world of literature in translation, Barthes’ claim reads more like a straightforward description of incontrovertible cultural and material realities: here, even a notionally single work such as Jane Eyre has a thousand entrances (or at least 618), while the voices coming from other texts (including other translations) have a strong and obvious influence, and the other codes are very markedly other, since language-difference can generate real incomprehension, as well as prompt bright insight.

This line of thought gives us an answer to the attack made by Franco Moretti on the role of close reading in world literary contexts:

The trouble with close reading (in all of its incarnations, from the new criticism to deconstruction) is that it necessarily depends on an extremely small canon. This may have become an unconscious and invisible premiss by now, but it is an iron one nonetheless: you invest so much in individual texts only if you think that very few of them really matter. Otherwise, it doesn’t make sense. And if you want to look beyond the canon (and of course, world literature will do so: it would be absurd if it didn’t!) close reading will not do it. It’s not designed to do it, it’s designed to do the opposite. At bottom, it’s a theological exercise — very solemn treatment of very few texts taken very seriously.7

To set this comment against the studies presented in this volume is to see how entirely Moretti overlooks the processes by which texts in fact circulate in world-literary contexts: through language(s), in hundreds of different versions, written by as many different people. This obviously complicates the notion of the canon. To be sure, Jane Eyre is a ‘canonical’ novel. But what that means in world-literary contexts is that it is opened up to all kinds of remaking: irreverent as well as reverent, casual as well as careful — reworkings for kids, for language-learners, for many different purposes in different places. And that is just the translations. The film versions, the manga versions, the theatre versions, the erotic versions, the continuations, the blogs, the merchandise — all these are even more carnivalesque. So the textuality that comprises and surrounds only one ‘canonical’ text in world-literary contexts is not extremely small. It is vast. All this — this individuality, variety, commitment, obstruction, invention, labour — all this is beneath the purview of distant reading. Yet it is through all this, and crucially through language(s), that world literature happens. It is in these trammels that people encounter it, read it, react to it, are changed by it and change it in their turn. And all this can only be seen by close reading, done collaboratively.

Collaboratively, and also selectively. For despite the many people involved in this project, what we have been able to read is still only part of what there is. And that part has not been subjected to a uniform methodology. The discussion of Chinese translations by Yunte Huang in some ways overlaps with the analysis of German translations by Mary Frank; but the two essays also pursue quite different avenues: they are in implicit dialogue, not methodological unison — and the same goes for all the essays. This heterogeneous approach embodies the commitment to collaboration, the openness to alternative epistemologies, and the recognition — indeed, the welcoming — of incompleteness which I announced in the Introduction and have been elaborating in Chapters I, II and III. As we have been seeing, the instances of the world Jane Eyre do not obey a uniform global ‘system’, and neither do they inhabit ‘languages’ in the sense of standardized structures. They exist in particular repertoires, cultures and temporalities, having been created by individuals in distinct material contexts; and they are encountered by readers who are people. The participants in this project, too, are people. And so, from their varied situations in the significant geography of this project, different aspects of the world Jane Eyre, as it is available to them through their own repertoires, strike them as interesting. And what is interesting is what we want to find out. They have selected the translations they wish to analyse on the basis of their judgment, and they have pursued the lines of enquiry that seem most profitable to them, given who they are, their intellectual commitments, and the material they are exploring. In the terms of the social sciences, the readings presented in the essays arise from ‘judgment or purposive sampling, or expert choice’.8 This procedure is no use for extracting statistics; but it is the only way of gaining access to a network with a thousand entrances — and that is what reading a world literary text requires us to do.

Almost all the approaches taken in individual essays could be pursued further afield. Widespread study of the handling of pronouns, of the language of appearance, or of indirect speech, for instance, are projects that could obviously be undertaken. That we have not done so is mainly down to practicality — of our capacities but also of yours, as readers, given the dimensions to which this volume has already grown. But it is also the case that these lines of enquiry turn out to be of variable fruitfulness in different locations — though it is impossible to be sure what will be interesting until you have looked. For instance, discussion starting from Léa Rychen’s Essay 14 suggested that Biblical intertextuality tended very often to be lost, and there was not much more to be said about it — but this does not mean that in some context and linguistic repertoire not represented in the conversation it might not be very interesting indeed. Likewise, the sort of creative attention to pronouns in German discovered by Mary Frank turned out — in the eyes of Céline Sabiron — not to be matched in French, though as Sowon S. Park pointed out, in languages with very different pronominal conventions, such as Korean, the picture was likely to be complicated in quite different ways. Again, the features described by Madli Kütt seemed to us to be specific to Estonian, with the caveat that there are many languages in which Jane Eyre has been translated that we were not able to study in detail. Various other lines of possible comparison across linguistic repertoires were tried out. We looked at rhythm; but it seemed that only Juan G. de Luaces, writing in Spanish in Barcelona in the early 1940s, showed any significant interest in responding to Brontë’s rhythms (see Essay 5 above, by Andrés Claro). We looked at patterns of metaphoricity, including pillars, water and fire. Here some points of interesting translinguistic comparison did emerge. For instance, Andrés Claro pointed out that the word ‘erect’, used by Brontë both for threatening patriarchal figures such as Mr Brocklehurst in Chapter 4 (‘the straight, narrow, sable-clad shape standing erect’) and for her own self-assertion before Mr Rochester in Chapter 23 (‘another effort set me at liberty, and I stood erect before him’) could not have been matched by Spanish translators with its obvious counterpart ‘erecto’ because the connotations were ‘too immediately phallic’. In Persian on the other hand, as Kayvan Tahmasebian explained, words relating to pillars and erectness tend to connote ‘support’ and therefore ‘dependence’, so alternatives have had to be sought. On the whole, however, it seemed that metaphoricity was best attended to in the repertoire-specific essays, as happens with fire in Essay 9 by Ana Teresa Marques dos Santos and Cláudia Pazos-Alonso below. Book-covers provided readier material for translinguistic comparison, as we have seen in Chapter III; and the variations in the titles and subtitles that have been given to the translations are suggestive too, as the following selection shows:

[Jane Eyre, or the Memoirs of a Governess]: Jane Eyre ou Mémoires d’une gouvernante, tr. ‘Old Nick’ (Paul Émile Daurand Forgues), French, 1849; Jane Eyre, eller en Gouvernantes Memoirer, translator unknown, Danish, 1850; Dzhenni Ėĭr, ili zapiski guvernantki tr. S. I. Koshlakova, Russian, 1857 … and many more, in many more languages.

[Jane Eyre, or the Orphan of Lowood]: Jane Eyre oder die Waise von Lowood, tr. A. Heinrich, German, 1854; Jane Eyre, of, De wees van Lowood: een verhaal, translator unknown, 1885; Dzhenni Ėĭr, Lokvudskaia sirota, Russian, 1893 … and many more.

[An Ideal Lady]: Riso Kaijin, tr. Futo Mizutani, Japanese, 1896.

[Seeing Light Again]: Chong guang ji, tr. Xiaomei Xu, Chinese, 1925.

[The Passion of Jane Eyre]: A Paixão de Jane Eyre, tr. ‘Mécia’ (João Gaspar Simões), Portuguese, 1941.

[Jane Eyre: A Sublime Woman]: Jane Eyre (A Mulher Sublime), tr. Virgínia Silva Lefreve, Portuguese, 1945.

[Orphan: Jane Eyre]: Yatim; subtitled ژن ئر, tr. Masʻud Barzin, Persian, 1950.

[Jane Eyre / Simple Love]: Jianai, tr. Fang Li, Chinese, 1954 … and almost every later Chinese translation.

[The Closed Door: Jane Eyre]: La porta chiusa (Iane Eyre), translator unknown, Italian 1958.

[True Love]: Kiè̂u giang, translator unknown, Vietnamese, 1963.

[When Everything Fails: A Novel of Jane Eyre]: Kapag bigo na ang lahat: hango sa Jane Eyre, translator unknown, Tagalog, 1985.

[Jane Eyre: Love Story]: Khwāmrak khǭng: Jane Eyre, tr. Sotsai Khatiwǭraphong, Thai, 2007.

[Jane Eyre: Happiness Coming After Many Years]: Jane Eyre: Yıllar Sonra Gelen Mutluluk, tr. Ceren Taştan, Turkish, 2010.

[The Human Life of the Girl Jane Eyre]: Bumo Dreng Ar gyi mitse (Bu mo sgreng ar gyi mi tshe), tr. Sonam Lhundrub, Tibetan, 2011.9

However, our most productive focus, as we looked together across the language(s) of the world Jane Eyre, turned out to be on individual words.

Key Words Refracting through Language(s)

In the text that Brontë wrote, networks of meaning grow through the repetition of particular words, words which gather significance as they recur. ‘Plain’ is a good example: across the span of the novel, Jane tells us that she wears ‘plain’ clothes (in the sense of ‘unelaborate’), looks ‘plain’ (‘unremarkable’), hears ‘plainly’ (‘clearly’), and is ‘too plain’ in her speech (‘blunt’); that her ‘Reason’ tells her a ‘plain, unvarnished tale’ (‘honest, frank’), and that she herself narrates the ‘plain truth’ (‘unembellished’). This last usage also jumps out of the fictional text into the Preface that Brontë wrote for the second edition, where she describes the novel as ‘a plain tale with few pretensions’.10 We will explore these reappearances of the word fully in Chapter VI below: watching it, as it steps up time and again to put its finger on something and name it, plainly, we may be tempted to feel, as William Empson did in The Structure of Complex Words, that:

a word may become a sort of solid entity, able to direct opinion, thought of as like a person; also it is often said (whether this is the same idea or not) that a word can become a ‘compacted doctrine’, or even that all words are compacted doctrines inherently.11

I would say, slightly differently, that the reiterations of the word signal an argument, one that is implicit also in the unfolding of the plot: plain looks can foster clarity of perception and straightforwardness of expression, and plainness, in this complex of senses, is a virtue. As the word is repeated, each new use can be tinged by those that have come before, so that its significance grows. We can draw on Empson again to say that, progressively, different senses of the word come to be ‘used at once’, creating ‘an implied assertion that they naturally belong together’.12

To take a selection of such key words, and to trace them through the novel, is to sample the endless drift and metamorphosis of vocabulary through time which was well described by Raymond Williams in Keywords:

We find a history and complexity of meanings; conscious changes, or consciously different uses; innovation, obsolescence, specialization, extension, overlap, transfer; or changes which are masked by a nominal continuity so that words which seem to have been there for centuries, with continuous general meanings, have come in fact to express radically different or radically variable, yet sometimes hardly noticed, meanings and implications of meaning.13

This is one aspect of the world of language(s), unstoppably burgeoning, subsiding, metamorphosing, and always exceeding the most patient attempts to chronicle it — such as those made by the enormous Oxford English Dictionary, a crucial source for both Williams and Empson. As its title announces, that dictionary (like many others) has another limitation: it is concerned only with the area of language(s) that counts as English. Both critics adopt the same focus, a constraint which causes Williams, at least, some frustration. He expresses it in a passage that I shall quote at length, since it is foundational to the volume that you are reading:

Of one particular limitation I have been very conscious. Many of the most important words that I have worked on either developed key meanings in languages other than English, or went through a complicated and interactive development in a number of major languages. Where I have been able in part to follow this, as in alienation or culture, its significance is so evident that we are bound to feel the lack of it when such tracing has not been possible. To do such comparative studies adequately would be an extraordinary international collaborative enterprise … I have had enough experience of trying to discuss two key English Marxist terms — base and superstructure — not only in relation to their German originals, but in discussions with French, Italian, Spanish, Russian and Swedish friends, in relation to their forms in these other languages, to know not only that the results are fascinating and difficult, but that such comparative analysis is crucially important, not just as philology, but as a central matter of intellectual clarity. It is greatly to be hoped that ways will be found of encouraging and supporting these comparative inquiries, but meanwhile it should be recorded that while some key developments, now of international importance, occurred first in English, many did not and in the end can only be understood when other languages are brought consistently into comparison.14

Prismatic Jane Eyre hopes to provide something of the comparative analysis that Williams wished for, even if it has its own necessary limitation, with its focus on a single world work. Yet this limitation does not mean that the words we have studied develop less complexity of meaning, as they spread across languages, than words like ‘base’ and ‘superstructure’ considered as part of transnational political discourse. Words in use can sprout new involutions in all sorts of ways; but a novel like Jane Eyre creates an especially charged context for their growth. Close-reading words in a literary text can uncover as much — or more — intricacy than attention to words in broader discourse, because literature is a forcing-house for language.

A quick example: three instances of the word ‘mind’ in the novel, with their Chinese translations by 宋兆霖 (Zhaolin Song), researched by Yunte Huang, and their Korean translations by 유 종호 (Ju JongHo) researched by Sowon S. Park. Here are the instances:

Then my sole relief was to walk along the corridor of the third story, backwards and forwards, safe in the silence and solitude of the spot, and allow my mind’s eye to dwell on whatever bright visions rose before it (Chapter 12).

Besides, I know what sort of a mind I have placed in communication with my own: I know it is one not liable to take infection: it is a peculiar mind: it is a unique one (Mr Rochester to Jane in Chapter 15).

Your mind is my treasure, and if it were broken, it would be my treasure still (Mr Rochester to Jane in Chapter 27).

In all these cases, Zhaolin Song translates ‘mind’ into 心灵 [xinling], which would usually be back-translated as ‘heart and spirit’, and Ju JongHo translates it as 마음 [ma um], which would usually be back-translated as ‘heart’. What issues come into play when we consider these displacements? We can point to general differences in the distribution of words, and so of their range of meanings, in the language(s) as used in these translations; and we can consider individual interpretive choices made by the translators, together with their cultural moments and the expectations of their audiences. But we can also look again at the text Brontë wrote, and notice the emotiveness and physicality surrounding ‘mind’ as it appears there. In the first instance, the visions of Jane’s mind’s eye open onto an imagined tale of ‘life, fire, feeling’; while the warmth of Mr Rochester’s use of the word is evident in the sentences quoted. In the history of English literary writing, what has more usually been said to be a ‘treasure’ that can be ‘broken’ is, not ‘mind’, but ‘chastity’.15 So, the choices made by the Chinese and Korean translators respond to an energy of imaginative possibility released by Brontë’s words. She uses ‘mind’ in a way that is unusually charged, and so has the potential to be translated into more embodied terms in language(s) that offer that choice.16

This instance can help us to articulate the difference between the variants explored by Prismatic Jane Eyre and those chronicled in the Vocabulaire Européen des philosophies: dictionnaire des intraduisibles, edited by Barbara Cassin, the book which is probably the truest fulfilment to date of Williams’s wish for comparative analyses of key words across languages (albeit only European ones in this case). Like Williams, Cassin sees the words as inhabiting a general sphere of usage — for her, the discourse of philosophy. What is discovered in the Vocabulaire, then, is:

la manière dont, d’une langue à l’autre, tant les mots que les réseaux conceptuels ne sont pas superposables — avec mind, entend-on la même chose qu’avec Geist ou qu’avec esprit … ?17

[how, from one language to another, neither words nor conceptual networks map onto one another exactly — by mind does one understand the same thing as by Geist or by esprit…?]

But in Prismatic Jane Eyre what comes into focus are not only general differences between what a word might be said to mean in one language and what a roughly equivalent word might mean in another (‘mind in English’ vs ‘Geist in German’) — indeed, as we saw in Chapter II, our study puts some pressure on the usefulness of ‘a language’ as an explanatory category. Rather, we attend to particular instances of usage, with the complexities of meaning, connotation and affect that erupt from them, and see how they are re-made with the always-partly-divergent and always-partly-continuous linguistic resources of translators with different repertoires in disparate moments and locations. Cassin feels able to identify particularly challenging philosophical terms, and label them ‘intraduisibles’ [‘untranslatables’] — a definition which, she says:

n’implique nullement que les termes en question, ou les expressions, les tours syntaxiques ou grammaticaux, ne soient pas traduits et ne puissent pas l’être — l’intraduisible, c’est plutôt ce qu’on ne cesse pas de (ne pas) traduire. Mais cela signale que leur traduction, dans une langue ou dans une autre, fait problème, au point de susciter parfois un néologisme ou l’imposition d’un nouveau sens sur un vieux mot.

[does not imply for a moment that the terms in question, and the expressions, the syntactic and grammatical constructions, are not translated and cannot be — the untranslatable is rather that which we never stop (not) translating. But this shows that their translation, in one language or another, creates problems, to the extent of sometimes requiring a neologism or the imposition of a new meaning on an old word.]

If unceasing, endlessly regenerative re-translation is the sign of the untranslatable, the index of ‘problems’, then the whole of Jane Eyre is untranslatable in Cassin’s sense — not just across Europe, but world-wide.

To see what is really going on here, we need to bring back into the picture all those linguistic fluidities and particularities which I described in Chapters I and II, and which Cassin’s conception of language here neglects — the variations in usage and in peoples’ repertoires, the continuities across language(s), and the ever-running rills and seepages of change. Any reader comes to Jane Eyre from their own location in language(s), and if they write down their reading as a translation it will be different from everyone else’s. Translation does not happen into ‘one language or another’ but always into particular repertoires. In the case of philosophical texts, the repertoires used are typically specialized and comparatively fixed. With these texts it may indeed be the case that a few words stand out as especially problematic and therefore ‘untranslatable’. But in the case of Jane Eyre — and this seems likely to be true of literature more broadly — anything at all, from a pronoun to a proper noun, can turn out to be, from someone’s point of view, and in relation to some linguistic repertoire, a generative crux.

One aspect of this generativity is brilliantly described by the linguist Christian M. I. M. Matthiessen. He adopts the term ‘agnate’ (which comes to him from H. A. Gleason via the work of Michael Halliday), using it to describe wording that might have been employed by a speaker or writer, but was not:

At any point in translation it may be one of these agnates rather than the actual expression that serves as the best candidate for translation … The agnates make up the source text’s shadow texts — texts that might have been because they fall within the potential of the language — and these shadow texts are thus also relevant to translation. By the same token, an actual translation exists against the background of shadow translations — possible alternative translations defined by the systemic potential of the target language.18

Any instance of a word, then, is haunted by the range of other words that it has been chosen from. The significance of their absent presence is conflicted. On the one hand, they accentuate the fact that the word on the page has been chosen — they prompt us to think that what matters most about it is what distinguishes it from them. On the other hand, they are nevertheless still invisibly there, and they bring with them the emotional and semantic hinterland from which the chosen word has emerged. For Matthiessen, the range of these possible shadow texts is limited by the concept of ‘a language’. In his model, there is a text-plus-shadow-texts in one standard language, and another text-plus-shadow-texts in another standard language, and the aim is to make the two sets match as closely as possible. However, once you remember that people do not just inhabit the standard language but have more complex repertoires, which are always varied and often multilingual, then the range of what can be seen as a shadow text expands. A moment from Jane Eyre that I discussed above in Chapter II is a good example:

I was a trifle beside myself; or rather out of myself, as the French would say.

The shadow text that has come into being in the vicinity of ‘beside myself’ is from French, ‘hors de moi’; and it has then been translated into the sequence of visibly written words, ‘out of myself’. So we need to reconceptualize shadow texts, not as being confined within the system of ‘a language’, but rather as spreading across space and time through the landscape of language difference — in this case not only ‘hors de moi’ but (moving to German) ‘außer mir’, as well as ‘I was mad with rage’ or ‘J’étais folle de rage’ or (moving into modern English) ‘I had totally lost it’, etc, etc, with domino after domino falling in whichever direction you would like to move. Shadow texts are not only what Jane (or Brontë) could have written but did not. They are also (by the same token) what someone else would have said in the same situation. They are, therefore, not only — as Matthiessen thinks them — ‘relevant to translation’: they are themselves translations into different repertoires. This repertoire may be only slightly divergent — in this case, alternative mid-nineteenth century tendencies in the range of language(s) Brontë knew (Standard English-French-German-Yorkshire). Or it may be located further afield — in modern English or anywhere else in the world landscape of language difference.

So when we watch key words refracting through languages, what we see are shadow text after shadow text appearing, as the world Jane Eyre moves into new locations across space and time, and stepping forward to take the place of the words written first by Brontë, just as ‘out of myself’ steps in to substitute for ‘beside myself’. We have already seen this happening to a small extent with the three instances of the word ‘mind’ in the Chinese and Korean translations by Zhaolin Song and Ju JongHo. Now let us observe a single instance of the word ‘glad’, as its shadows form in new repertoires and locations, in a series of translations across French, German, Slovenian, Persian and (again) Chinese, which have been researched, respectively, by Céline Sabiron, Mary Frank, Jernej Habjan, Kayvan Tahmasebian and Yunte Huang. The instance in Brontë’s text comes at the start of the second paragraph of the novel, where, having told us about the bad weather and the impossibility of taking a walk, Jane for the first time asserts herself using the first person, and sets herself starkly apart from the mood that has been established: ‘I was glad of it: I never liked long walks …’. Now here are the translations:

J’en étais contente [I was glad of it] (Lesbazeilles-Souvestre, 1854; also Brodovikoff and Robert, 1946 and Monod, 1966)

Ich war von Herzen froh darüber [I was happy about it from my heart] (von Borch, 1888)

Je n’en étais pas fâchée [I was not angry/upset about it] (Gilbert and Duvivier, 1919)

Je m’en réjouis [I was well pleased about it] (Redon and Dulong, 1946)

Meni je bilo kar všeč [I rather liked it] (Borko and Dolenc, 1955)

J’en étais heureuse [I was happy about it] (Maurat, 1964)

Bilo mi je kar prav [This agreed with me actually] (Legiša-Velikonja, 1970)

Mir war es nur Recht [It was only right to me] (Kossodo, 1979)

خوشحال بودم [I had a good feeling (khush-hāl) of it] (Bahrami Horran, 1991; also Reza'i, 2010)

这倒让我高兴 [It contrarily made me glad, rendering ‘glad’ as 高兴 (gaoxing), ‘high and rising (in spirit or mood)’, a Chinese equivalent of feeling ‘up’] (Song Zhaolin, 2002)

J’en étais ravie’ [I was delighted with it] (Jean, 2008)

Mich freute es [It pleased me] (Walz, 2015)

As always, any of these instances could nourish an interpretation focusing on the contextual factors that have helped it into being (many of the essays in this volume offer such readings). On the other hand, by looking at the quotations together, in a decontextualized array, we can form a vivid sense of the signifying possibilities generated by Brontë’s word ‘glad’ at this point in the text. As it moves into new locations and repertoires, different shadow texts step forward to take its place. We have represented them in English with back translations which are (as ever) not exact equivalents of them, any more than they are exact equivalents of ‘glad’. Nevertheless, as shadow texts of shadow texts, the back translations can register in English something of the range that opens up: ‘glad’ can move in the direction of happy, pleased, delighted, not upset, I liked it, it was right, it agreed with me, I had a good feeling, it made me feel ‘up’. Each translator has searched out something that sounds right in their repertoire, a ringing turn of phrase to match the energy of Brontë’s. This particular explosion of plurality, then, is an indication of the emotional charge of the moment; and it also directs us back to the particular word that Brontë chose, rather than the alternatives that are thrown up in the back translations. Why ‘glad of it’, exactly, rather than ‘I was pleased’ or ‘I was happy’?

It turns out that ‘glad’ is a distinctive word for Jane. She does not use it particularly often (in fact, it appears less frequently in Jane Eyre than in comparable novels such as E. C. Gaskell’s North and South or Dickens’s David Copperfield). In those books, the word often functions as part of a formula in polite conversation, and this usage does sometimes occur in Jane Eyre too: ‘Mr. Rochester would be glad if you and your pupil would take tea with him’.19 But more often (and this is what is distinctive) it is used in the vein we have begun to explore: a powerful expression of individual feeling. Here are some more examples:

‘I am glad you are no relation of mine: I will never call you aunt again as long as I live.’ (The young Jane to Mrs Reed)

How glad I was to behold a prospect of getting something to eat! (at Lowood school)

I felt glad as the road shortened before me: so glad that I stopped once to ask myself what that joy meant: (returning to Thornfield from Mrs Reed’s deathbed)

‘Oh, I am glad! — I am glad!’ I exclaimed. … ‘I say again, I am glad!’ (Jane to St John Rivers on learning that the Rivers family are her relations)

Gladdening words! (At Thornfield after the fire, on learning that Mr Rochester is still alive)

‘God bless you, sir! I am glad to be so near you again.’ (To Mr Rochester, near the end of the novel).20

As ‘glad’ recurs in Jane’s mouth it becomes a vehement, individual, bodily word, one that voices relief when danger is avoided or suffering escaped, and relish when a joy is gained. In all this, it is differentiated from ‘happy’ which appears more frequently, and in a wider range of uses, and which often has something conventional about it. These contrasting strands of meaning are signalled right at the start when — as we saw in Chapter II — the novel introduces some key aspects of its language(s) as well as of its spatial and interpersonal dynamics. While Jane is ‘glad’ at the cancellation of the walk, Mrs Reed is ‘perfectly happy’ as she reclines ‘on a sofa by the fireside with her darlings about her’ — a group from which Jane is debarred, as Mrs Reed tells her that ‘she really must exclude me from privileges intended only for contented, happy, little children’. So Jane goes to take refuge with ‘Bewick’s History of British Birds’ in the window-seat in the breakfast room, and tells us: ‘I was then happy: happy at least in my way.’ This sequence puts a question-mark over the value of being ‘happy’ which lingers throughout the novel, even to the very last appearance of the word in the final chapter: ‘my Edward and I, then, are happy: and the more so, because those we most love are happy likewise’. In the sequence of the narrative, the apparent tranquillity of this utterance is disrupted by the turn to St John Rivers, and the jarring, brief description of his work as an ‘indefatigable pioneer’ in ‘India’.21 This reaffirms what we have already learned from its earlier recurrences: that ‘happy’ is not a straightforward word. Like other novels in the Bildungsroman genre, Jane Eyre asks: what happens when the individual joins the couple or the social, when the visceral settles into the conventional. One of the ways it puts the question is by showing ‘glad’ giving way to ‘happy’.

Neither ‘glad’ nor ‘happy’ is as complex a word as ‘plain’ (nor, we will see, as ‘passion’). But the relationship between the two terms is part of the network of co-ordinates that organises the signifying material of the novel. Studying the proliferation of shadow texts created by the first appearance of ‘glad’ has helped us to see this; however, as it turns out, the distinction between ‘glad’ and ‘happy’ is not consistently tracked in any of those translations. In all of them, as the novel progresses, words that stand in for ‘glad’ can also stand in for ‘happy’, so a significant distinction dissolves into a differently significant continuum. When this happens, one needs to read the translations for the new patterns that they create for themselves, as we will see in the discussions of ‘ugly’, ‘laid(e)’ and ‘brutto/a’, as well as the Persian word ‘parsa’, in Chapter VII.

Sometimes, a pattern of repetition is preserved almost unchanged through many translations. When this happens, though the look of a word has altered, and probably also its connotations, the structuring influence of its recurrences persists. One striking example is ‘conscience’, a powerful word in the novel and in Jane’s mental life. Its healing strength is urged on the young Jane by Helen Burns at Lowood; and when she discovers the existence of Mr Rochester’s wife Bertha it is Conscience (now capitalised) that tells her she must leave him.22 In translations into French studied by Céline Sabiron, into Spanish studied by Ana Teresa Marques dos Santos, into Danish studied by Ida Klitgård, and into Slovenian studied by Jernej Habjan, the same word recurs wherever ‘conscience’ recurs (‘conscience’, ‘conciencia’, ‘samvittighed’, ‘vest’). And this continues to be true of translations into languages where religious traditions other than Christianity are dominant: of those into Arabic studied by Yousif M. Qasmiyeh (ضمير [dameer]), into Persian studied by Kayvan Tahmasebian (وجدان [vijdān]), and into Korean studied by Sowon S. Park (양심 [yang shim]).

Often, a pattern is partly preserved and partly broken. One instance is ‘master’, a word which, in Brontë’s text, spans the mode of address to a young gentleman (‘Master Reed’), the job title of a schoolmaster (‘Mr Miles, the master’), and Jane’s at once professional and passionate appellation for Mr Rochester (‘my master’). In all the translations studied by Mary Frank in German, by Jernej Habjan in Slovenian, by Andrés Claro in Spanish, by Kayvan Tahmasebian in Persian, and by Eugenia Kelbert in Russian, the vocabulary available in those languages splits off the first two kinds of usage from the last. Another, more complex, and more fascinating instance, is ‘passion’: let us turn to it straight away, in Chapter V.

Works Cited

For the translations of Jane Eyre referred to, please see the List of Translations at the end of this book.

Barthes, Roland, S/Z (Paris: Seuil, 1970).

Brooks, Cleanth, The Well Wrought Urn: Studies in the Structure of Poetry (London: Dobson Books, 1949).

Cayley, John, Programmatology, https://programmatology.shadoof.net/index.php

Empson, William, The Structure of Complex Words (London: The Hogarth Press, 1985 [1951]).

Kalton, Graham, Introduction to Survey Sampling (Beverly Hills, Calif.: Sage Publications, 1983).

Kristeva, Julia, Semiotiké: Recherches pour une sémanalyse (Paris: Seuil, 1969).

Levinson, Marjorie, ‘What is New Formalism?’, PMLA 122 (2007), 558–69, https://doi.org/10.1632/pmla.2007.122.2.558

Matthiessen, Christian M. I. M., ‘The environments of translation’, in Text, Translation, Computational Processing [TTCP]: Exploring Translation and Multilingual Text Production: Beyond Content, ed. by Erich Steiner and Colin Yallop (Berlin and New York: Mouton de Gruyter, 2013), pp. 41–124, https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110866193.41

Moretti, Franco ‘Conjectures on World Literature’ New Left Review, new series 1 (2000), 54–68.

Reynolds, Matthew, Mohamed-Salah Omri and Ben Morgan, ‘Introduction’, Comparative Critical Studies, special issue on Comparative Criticism: Histories and Methods, 12, 2 (2015), 147–59, https://doi.org/10.3366/ccs.2015.0164

Raymond Williams, Keywords: A Vocabulary of Culture and Society (London: Harper Collins 1988 [1976; revised edn 1983]).

Wolfson, Susan, ‘Reading for Form’, Modern Language Quarterly 61 (2000), 1–16, https://doi.org/10.1215/00267929-61-1-1

1 This view builds on the conception of comparative criticism described in Matthew Reynolds, Mohamed-Salah Omri and Ben Morgan, ‘Introduction’, Comparative Critical Studies, special issue on Comparative Criticism: Histories and Methods, 12, 2 (2015), 147–59.

2 Marjorie Levinson, ‘What is New Formalism?’, PMLA 122 (2007), 558–69 (p. 559); see Susan Wolfson, ‘Reading for Form’, Modern Language Quarterly 61 (2000), 1–16 (p. 2).

3 Cleanth Brooks, The Well Wrought Urn: Studies in the Structure of Poetry (London: Dobson Books, 1949), p. 195.

4 Roland Barthes, S/Z (Paris: Seuil, 1970), p. 18.

5 Julia Kristeva, Semiotiké: Recherches pour une sémanalyse (Paris: Seuil, 1969).

6 Barthes, S/Z, p. 19.

7 Franco Moretti, ‘Conjectures on World Literature’ New Left Review, new series 1 (2000), 54–68 (p. 57).

8 Graham Kalton, Introduction to Survey Sampling (Beverly Hills, Calif.: Sage Publications, 1983), p. 91.

9 These titles were researched by Rachel Dryden, Chelsea Haith, Céline Sabiron, Vincent Thierry, Léa Rychen, Ida Klitgård, Eugenia Kelbert, Mary Frank, Jernej Habjan, Ana Teresa Marques dos Santos, Claudia Pazos Alonso, Kayvan Tahmasebian, Yunte Huang, Alessandro Grilli, Yorimitsu Hashimoto, Emrah Serdan, Ulrich Timme Kragh, Livia Demetriou-Erdal.

10 See Chapter VI, ‘“Plain” through Language(s)’ for the references for these quotations, and full discussion.

11 William Empson, The Structure of Complex Words (London: The Hogarth Press, 1985 [1951]), p. 39.

12 Empson, Structure, p. 40.

13 Raymond Williams, Keywords: A Vocabulary of Culture and Society (London: Harper Collins 1988 [1976; revised edn 1983]), p. 16.

14 Williams, Keywords, p. 18.

15 For instance, this characteristic C17th instance by James Shirley, The Wedding (London: printed for John Groue [etc], 1629), act 2, scene 1, line 75: ‘the treasures of her chastity / Rifled’; the idiom survived into the C19th, as in Michael Field, Brutus Ultor (Clifton: J. Baker & Son — George Bell & Sons, 1886), p. 26: ‘there’s no treasure there, / No chastity’. Quoted from Proquest Literature Online, https://www.proquest.com/lion.

16 For in-depth discussion of ‘mind’ in Portuguese, see Essay 9 below, by Ana Teresa Marques dos Santos and Cláudia Pazos-Alonso.

17 Pp. xvii–xviii.

18 Christian M. I. M. Matthiessen ‘The environments of translation’, in Text, Translation, Computational Processing [TTCP]: Exploring Translation and Multilingual Text Production: Beyond Content, ed. by Erich Steiner and Colin Yallop (Berlin and New York: Mouton de Gruyter, 2013), pp. 41–126 (p. 83).

19 JE, Ch. 13.

20 JE, Chs 4, 5, 22, 33, 36, 37.

21 See Essay 1, by Ulrich Timme Kragh and Abhishek Jain for discussion of this passage.

22 JE, Chs 8, 27.