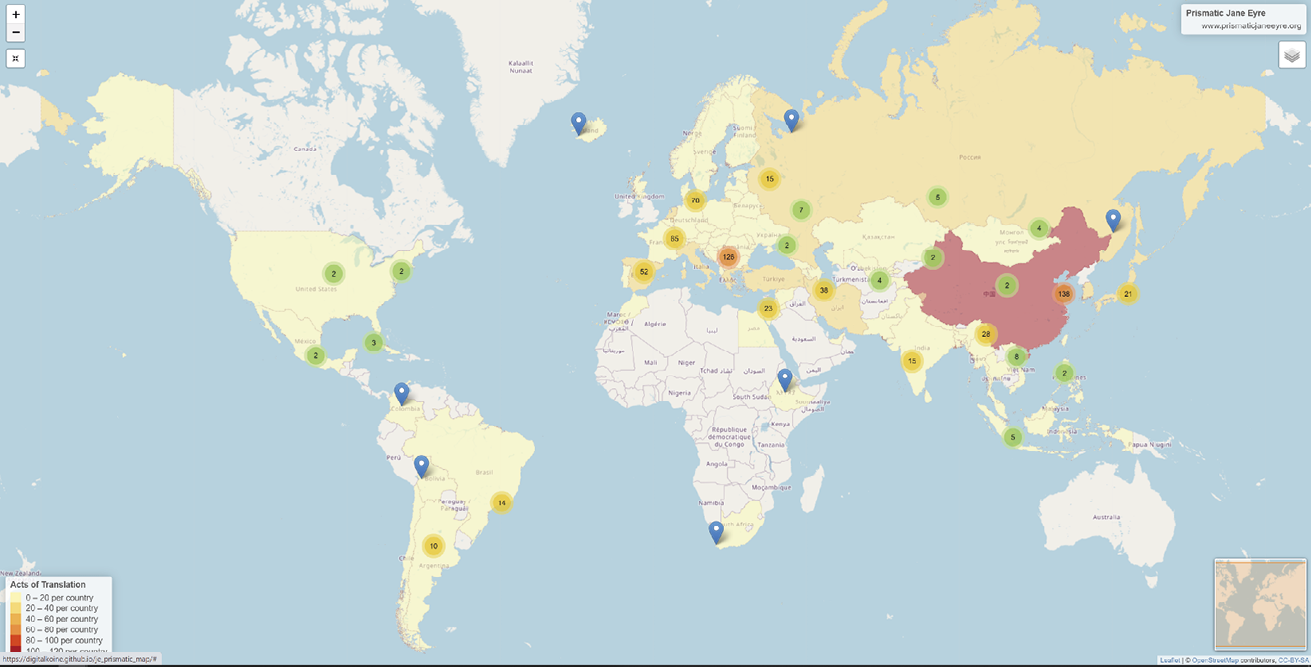

The World Map https://digitalkoine.github.io/je_prismatic_map Created by Giovanni Pietro Vitali; maps © Thunderforest, data © OpenStreetMap contributors

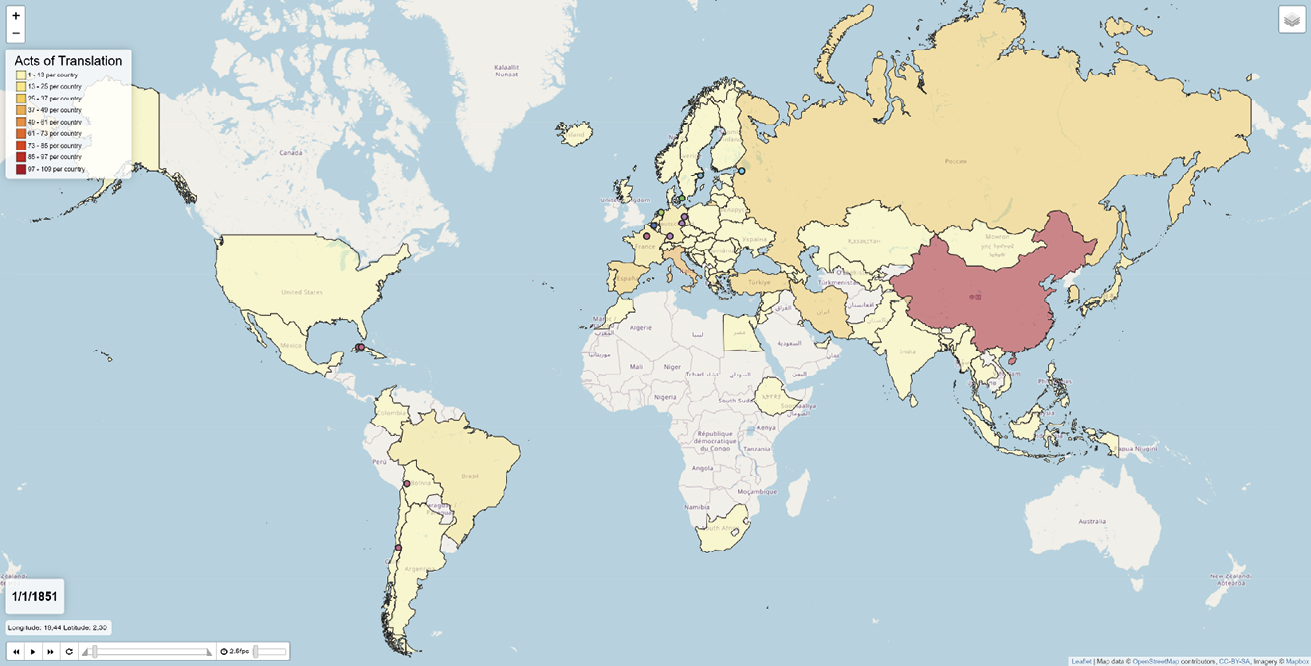

The Time Map https://digitalkoine.github.io/translations_timemap Created by Giovanni Pietro Vitali and Simone Landucci;© OpenStreetMap contributors, © Mapbox

V. ‘Passion’ through Language(s)

© 2023 Matthew Reynolds, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0319.14

‘You are passionate’, says Mrs Reed to the young Jane early on, and the novel conducts an extended exploration of what that might mean. ‘Passion’ (with ‘passionate’ and ‘impassioned’) appears 43 times, with its varied possible meanings surfacing to different degrees at different moments. Jane is passionate in her resistance to bullying in the Reed family and injustice at Lowood school; she and Mr Rochester are passionate in their relationship with one another; St John Rivers is passionate in his missionary zeal. ‘Passion’ can connote anger, stubbornness, vehemence, suffering, wilfulness, intensity, desire, love, generosity, unhappiness, devotion, and fanaticism. It is a root, perhaps the root of selfhood; yet it also needs to be controlled by ‘conscience’ and ‘judgment’.

The word’s reappearances throughout the novel work somewhat like a pattern of rhyme in a poem. They establish connections between the multiple meanings of ‘passion’ and suggest ways of understanding the relationships between them. As with an Empsonian complex word (discussed in Chapter IV), Brontë’s handling of ‘passion’ implies an argument: passion in the sense of love is continuous with passion in the sense of rage; love is a mode of self-assertion and self-fulfilment for women no less than for men. Yet the novel also worries at the word in ways that are too knotted for easy summary: ‘passion’ is exalted, diminished, attacked, and viewed with wonder.

The complexities inherent in the word ‘passion’ were not invented by Brontë, of course, nor are they specific to the English language. Passion is shared with French (passion), Italian (passione), Spanish (pasión), Romanian (pasiune), Portuguese (paixão), and it derives from the Latin passio, itself influenced by translation from the Greek πάθος (pathos). Tracing ‘passion’ in Jane Eyre across these closely related areas of the global landscape of language variation allows us to gauge the distinctiveness of the meaning-making resources of Brontë’s English, and the way she put them to use. Take the French ‘passion’. It looks identical to the English version of the word, and can enable moments of perfect word-for-word translation, as in the heart-rending passage in Chapter 27 where, after the failure of the wedding, Jane resolves to leave Thornfield:

Conscience, turned tyrant, held Passion by the throat

ma conscience devenait tyrannique, tenait ma passion à la gorge (F1854)

ma conscience, muée en tyran, saisit la passion à la gorge (F1964)

et la Conscience, muée en despote, tenait la Passion à la gorge (F1966)

la conscience devenue tyrannique prenait la passion à la gorge (F2008)1

But ‘passion’ in French does not correspond so readily to the angrier reaches of ‘passion’ in English. In such cases — as Céline Sabiron points out — the French translations ‘tend to specify what is meant’ using other words, as here in Chapter 2 where Bessie is chiding the young Jane:

… if you become passionate and rude, Missis will send you away, I am sure.

si vous devenez brutale et en colère (F1854) [if you become brutal and angry]

si vous devenez violente et grossière (F1946) [violent and rude]

si vous devenez emportée, violente (F1964) [fiery, violent]

si vous devenez coléreuse et brutale (F1966) [quick-tempered and brutal]

vous vous montrez violente et désagréable (F2008) [violent and disagreeable]

The varying translations are interesting for several reasons. They can help us imagine our way into the implications of the English ‘passionate’ here. They trace a mini-history of shifts in taste and usage in French across different translators and different times. And they show that the French ‘passion’ and English ‘passion’ cast different nets across the material of the novel, joining up experience in different ways.

In other languages, the picture is sometimes quite similar to the French, even though the word that corresponds to ‘passion’ has a different etymology. In Russian — as Eugenia Kelbert points out — there is ‘a direct analogue of “passion” (“страсть [strast’]”, adj. “страстный [strastnyĭ]”) but it has strong romantic/sexual connotations, as well as religious significance, since strasti refer both to the passions of Christ and to the deadly sins, eight in number in the Russian Orthodox tradition, which include anger as well as lust’. Nevertheless, the angrier instances of ‘passion’ tend to be rendered by other words. This varies between the translations, though: ‘for example, Stanevich’s 1950 translation uses “страсть” [strast’] twice less frequently than Gurova’s in 1999’.

Other tongues draw in a multitude of words to cover the semantic range of Brontë’s ‘passion’. In Arabic, as Yousif M. Qasmiyeh explains, ‘passion has multiple equivalences, depending on the connotation, context and those involved. At times it carries the meaning of a reaction or a response to a state of being: “انفعال [infiʿāl]”. At other times it connotes anger and frustration: “حنق [ḥanq]”. When it is associated with love and/or having feelings for other people, the words used are: “حب [ḥubb]” (love) which is conventionally modified by an adjective, “عاطفة [ʿātifa]”, and “هوى [hawā]” which is a synonym of “حب [ḥubb]” and conveys the act of falling in(to) another state of being.’ In Persian too — Kayvan Tahmasebian tells us — ‘“passion” corresponds to a wide range of diverse words from “شور [shūr]” (literally, “excitement”), “عشق [ʿishq]” (literally, “love”), “تمنا [tamannā]” (literally, “strong desire”) and “خشم [khashm]” (literally, “anger”). Because of this indeterminacy, “passion” is usually translated into redundant structures where two nearly similar words are joined by “and”.’

In what follows, you can explore the various reconfigurations of ‘passion’ generated by different translations and languages.

A Picture of Passion

We are at the end of Chapter 1, where the young Jane is attacked by her cousin John Reed, and fights back. He ‘bellowed out loud’ and Mrs Reed arrives with the servants Bessie and Abbott. The fighting children are parted, and Jane hears the words:

‘Dear! dear! What a fury to fly at Master John!’

‘Did ever anybody see such a picture of passion!’

This is the first appearance of ‘passion’ in the novel, and ‘picture’ is an interesting word to attach to it. Jane has just been reading the illustrated Bewick’s Book of British Birds, in which ‘each picture told a story’; and later in the novel the pictures she draws will be similarly eloquent. The phrase ‘picture of passion’ feels as though it might be proverbial; but a database search uncovers only one instance in English-language literature before this moment.2 In context, it sounds like a colloquial idiom, more likely to be uttered by Abbott or Bessie than by Mrs Reed. And in fact the lady of the house chimes in next, in her commanding tones: ‘“Take her away to the red-room, and lock her in there.”’ So a brief social drama unfolds in response to the little Jane’s act of resistance: the startled expostulations of the servants creating the conditions in which a member of the gentry lays down the law.

In the translations, as you can see in the animation and static array below, the idea of the picture sometimes remains and sometimes drops away. In French it tends to morph into the slightly less material ‘image’; in Dèttore’s 1974 Italian translation it becomes more dramatic, a ‘scena’ or theatrical scene. Almost all the translations continue the idea that what is happening here is something that strikes the sight, that has never been ‘seen’ before. On the other hand, almost all are required by the habits of their languages to break the link between this moment and Jane’s later passion (in the sense of love): they render ‘passion’ with words that can be back-translated as ‘anger’, ‘stubbornness’, ‘impertinence’, ‘mad’, ‘fury’, ‘rage’, and suchlike. The consequence is that this moment becomes visibly connected to the anger, pain and madness of Bertha Rochester as they are revealed later in the novel. Ana Teresa Marques dos Santos points out that this tendency is especially marked in the Portuguese translations by ‘Mécia’ (1941) and Ferreira (1951) which use ‘monstro’ (monster) and ‘ferazinha’ (little beast’). Adriana X. Jacobs notes that Bar’s 1986 Hebrew translation makes a more subtle gesture in the same direction, using a word, ‘משולהבת [meshulhevet]’, which derives from shalhevet (flame).

Only Dèttore takes a different tack, making the words express the emotion of whoever it is who speaks them, rather than attributing feeling to Jane: ‘Si è mai vista una scena così pietosa?’ (Have you ever seen such a pitiful scene?) Paola Gaudio points out that ‘pietosa’ here connotes ‘miserable’, ‘pathetic’ and ‘embarrassing’. Yet it also perhaps — as Jane is held and then carried off — brings with it a hint of a Pietà, the scene of Mary holding Christ’s body and mourning him, which follows the passion of Christ on the cross in traditional narratives of the crucifixion. This thread of suggestion cannot be said to be visible in the English alone; but it is latent in the weave of language(s) and culture(s) from which Jane Eyre is formed. It becomes more prominent in translation.

These prismatic variants occupy a complex conceptual space. They have come into being successively through time and across geographical distances; but equally they all co-exist simultaneously in the textual reality of the world work Jane Eyre as it currently exists. So I present them to you in two ways. First, in an animated form, inspired by the (much more accomplished) digital artworks created by John Cayley;3 and, second, in a static array, inspired by traditional variorum editions. The two modes of presentation also encourage two modes of reading: the first perhaps more aesthetically receptive, the second perhaps more informational and analytic. As ever, all publication details for the translations quoted can be found in the List of Translations at the end of this volume: the abbreviations in the animations and static arrays start with an indicator of the language, then the year of first publication and then — if there is more than one translation into that language for that year — the first letter of the translator’s name. For instance: It2014S means the Italian translation, published in 2014, by the translator whose name begins with S — that is, Stella Sacchini (Milan: Feltrinelli).4

Animation 1: a picture of passion

https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12434/60f44705

D2015 hidsighed [hot-temperedness]

Por2011 Mas onde é que já se viu uma fúria destas?! [Have you ever seen such a fury?]

It2010 Si è mai vista una collera simile? [Did you ever see an anger like it?]

F2008 une telle image de la colère [such an image of anger]

K2004 꼴 [{Kkol} face]

He1986 ראיתם פעם תמונה משולהבת כזאת [{ra’item pa’am temuna meshulhevet ka-zot} Did you ever see such an ecstatic picture?]

It1974 Si è mai vista una scena così pietosa? [Have you ever seen such a pitiful scene?]

F1964 semblable image de la passion! [similar image of passion!]

Sp1941 ¡Con cuánta rabia! [With so much rage!]

Por1951 Se já se viu uma coisa destas!… É uma ferazinha! [Have you ever seen a thing such as this one?… She’s a little beast!]

R1950 Этакая злоба у девочки! [{Ėtakaia zloba u devochki} What malice that child has!]

F1946 pareille image de la colère [such an image of anger]

Por1941 Onde é que já se viu um monstro destes?! [Have you ever seen a monster such as this one?]

F1919 pareille forcenée [such a mad person/a fury]

R1901 Видѣлъ-ли кто-нибудь подобное бѣшенное созданіе! [{Vidiel li kto-nibud’ podobnoe bieshennoye sozdaníe} Has anyone seen such a furious (lit. driven by rabies) creature!]

Did ever anybody see such a picture of passion!

R1849 Кто бы могъ вообразить такую страшную картину! Она готова была растерзать и задушить бѣднаго мальчика! [{Kto by mog voobrazit’ takuiu strashnuiu kartinu! Ona gotova byla rasterzat’ i zadushit’ biednago mal’chika} Who could have imagined such a terrible sight/picture! She was ready to tear the poor boy apart and strangle him!]

It1904 Avete mai visto una rabbiosa come questa? [Have you ever seen a girl as angry as this one?]

Por1926 Já viu alguem tal accesso de loucura ! [Has anyone ever seen such a madness fit?]

He1946 ?הראה אדם מעולם התפרצות כגון זו [{hera’e adam me-olam hitpartsut kegon zo} Has anyone ever seen an outburst like that one?]

Sp1947 ¿Habráse visto nunca semejante furia? [Have you ever seen such fury?]

It1951 Non s’è mai vista tanta prepotenza! [I’ve never seen such impertinence]

Sl1955 jeza [fury]

Sl1970 ihta [stubbornness]

A1985 هل قدر لأي امرئ أن يرى مثل هذا الانفعال من قبل؟ [{hal quddira li ayy imriʾ an yarā mithla hadha al infiʿāl} Was anyone ever destined to see such a reaction]

R1999 Просто невообразимо, до чего она разъярилась! [{Prosto nevoobrazimo, do chego ona raz’’arilas’!} It simply passes imagination how furious she is]

He2007 !?ראיתם פעם פראות כזאת [{ra’item pa’am pir’ut ka-zot?} Did you ever see such wildness?!]

Sp2009 ¡Habrase visto alguna vez rabia semejante! [Have you ever seen such rage!]

Pe2010 تا حالا چنین خشم و عصبانیتی از کسی ندیده بودیم [{tā hālā chunīn khashm va ʿasabāniyatī az kasī nadīda būdīm} We had not seen such a rage and anger]

T2011 སྨྱོན་མ་འདི་འདྲ་སུས་མཐོང་མྱོང་ཡོད་དམ [{smyon ma 'di 'dra sus mthong myong yod dam} Has anyone ever seen such a crazy woman?]

D2016 raseri [anger, wrath]

A Passion of Resentment

In Chapter 4, the young Jane has been present at the interview between Mrs Reed, her aunt, and Mr Brocklehurst, the forbidding visitor who has come to assess her suitability for Lowood school. She has heard herself described as ‘an artful, noxious child’ possessing ‘a tendency to deceit’. Sitting there, she says, ‘I had felt every word as acutely as I had heard it plainly, and a passion of resentment fermented now within me.’

The phrasing, with its emphasis on feeling and hearing, accentuates the sense of ‘passion’ as the reaction to a stimulus that has come from outside (to which Jane has been passive); in response, passion ‘ferments’ like wine or beer in the making. There is a variant here in the English texts of Jane Eyre: the second and third editions print ‘fomented’ (i.e., warmed, cherished) instead of ‘fermented’ which is in the manuscript and first edition. Both readings can be found in later editions, and have been used by translators.

In the translations, ‘passion of resentment’ is rephrased in ways that give rise to different, sometimes more violent back-translations: ‘unbearable rage’, ‘lust for vengeance’, ‘intense anger’. The hint of liquid in ‘fermented’ plays out in varied directions: ‘passionate thirst for vengeance’; ‘indignation started to boil within me’; ‘indignation was ready to pour forth torrent-like from my chest’. In the Tibetan translation, which is comprehensively abridged, much of the preceding dialogue and description are cut, but this moment of passion is preserved and intensified.5

Animation 2: a passion of resentment

https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12434/3b5761b6

D2016 lidenskabelig følelse [passionate feeling]

Pe2010 بیزاری و خشم در وجودم میجوشید [{bīzārī va khashm dar vujūdam mījūshīd} resentment and rage was boiling in me]

R1999 Теперь же во мне закипало возмущение [{Teper’ zhe vo mne zakipalo vozmushcheniye} And now indignation started to boil within me]

It1974 un impeto di risentimento ribolliva dentro di me [an impetus of resentment was boiling over inside me]

Sl1955 srd po maščevanju [lust for vengeance]

R1950 и во мне пробуждалось горячее желание отомстить [{i vo mne probuzhdalos’ goriachee zhelanie otomstit’} and an ardent wish to avenge myself was awakening within me]

R1901 и безумная жажда мести зародилась и стала рости въ моемъ сердцѣ [{i bezumnaia zhazhda mesti zarodilas’ i stala rosti v” moem” serdtsie} and an insane thirst for revenge was born and grew in my heart]

I had felt every word as acutely as I had heard it plainly, and a passion of resentment fermented now within me.

R1849 и негодованіе готово было излиться бурнымъ потокомъ изъ моей груди [{i negodovanīe gotovo bylo izlit’sia burnym” potokom” iz” moeĭ grudi} indignation was ready to pour forth torrent-like from my chest]

It1904 e stavo là, agitata da un vivo risentimento [and there I sat, agitated by a vivid resentment]

It1951 un cupo risentimento mi agitava tutta [a dark resentment was shaking all of me]

Sl1970 strastna maščevalnost [passionate thirst for vengeance]

A1985فاذا بحنق شديد يعتمل في ذات نفسي [{fa idhā bi ḥanq Shadīd yaʿtamil fī dhāt nafsī} [suddenly/then an unbearable rage began to boil in/at my very core]

K2004 감정[{gam jung} emotion]

T2011 ང་ལ་བློ་སྤོབས་ཆེན་པོ་ཞིག་སྐྱེས་པས་རང་ཉིད་ཀྱི་ཁོང་ཁྲོ་མེ་ལྕེ་བཞིན་འབར་བ་བཅོས་མིན་དུ་མངོན་པ་ན་ལྕམ་མོ་རེའུ་ཏི་ལ་ཞེད་སྣང་སྐྱེས་པ་དང་འདུག་ལ། [{nga la blo spobs chen po zhig skyes pas rang nyid kyi khong khro me lce bzhin 'bar ba bcos min du mngon pa na lcam mo re'u ti la zhed snang skyes pa dang 'dug la} Since a great courage arose within me, I felt an intense anger burn within me like a flame of fire, while a sense of aggression/fear towards Madam Reed appeared in me]

It2014 e l’ira e il risentimento montavano ora dentro di me [and now anger and resentment were building up inside me]

A “Grande Passion”’

In Chapter 15, Mr Rochester explains to Jane how her French pupil Adèle came to be at Thornfield Hall: ‘she was the daughter of a French opera dancer, Céline Varens; towards whom he had once cherished what he called a “grande passion.” This passion Céline had professed to return with even superior ardour.’ Mr Rochester uses a French phrase, though one that is readily comprehensible in English, to veil his affair and distance himself from it, introducing a note of melodrama and exoticism. If you call something a ‘grande passion’ you may well mean to suggest that it is not so deep-rooted as a ‘great passion’ would have been (‘“une grande passion” is “une grande folie”’, as Brontë wrote in a letter to her friend Ellen Nussey.)6 In the next sentence, Jane, narrating, translates the French ‘passion’ into English ‘passion’ as Rochester’s passion is reflected by Céline. In this English translation the question of honesty is made explicit: his ‘“grande passion”’ (a French phrase used by an Englishman) may be hot-headed, but her ‘passion’ (now an English word used of a French woman) is only ‘professed’. Translation within the text becomes a means of ethical appraisal.

The translators often recreate the switch from French ‘passion’ to an equivalent in their language, though nowhere is the spelling identical as it is with the French/English word. Sometimes, a language’s liberty with pronouns enables a translator to put the two terms exactly side by side (Hill, Sp2009: ‘… passion. Pasiòn …’; Pareschi, It2014: ‘… passion. Passione …’). Sometimes ‘passion’ is glossed, creating a bridge towards the description of Céline’s response (as with Stanevich, R1950); sometimes she is allowed the French word too (Rohde, D2016R); sometimes the connection is made by a switch from verb to noun (Ferreira, Por1951); sometimes the translational jump from Mr Rochester’s ‘passion’ to her equivalent is abandoned, and her professed feeling is described in different terms; and sometimes the same word, in the language of the translation, is used for both Mr Rochester’s and Céline’s actual or apparent feelings, as in Ben Dov’s use of ‘תשוקה [teshuka]’, He1946 (followed by Bar, He1986). As Adriana X. Jacobs comments: ‘In Hebrew, “teshuka” is related to the root sh.u.k., to run after, often used in the sense of longing and physical desire (in Rabbinic literature, the desire of a wife for her husband)’.

In each case, the translators are re-creating in their own language the sparks (including a spark of irony) that jump between the two kinds — two languages — of passion that Brontë imagined and wrote down. They are answering Brontë’s text more intimately than Céline has answered to Mr Rochester.7

Animation 3: a ‘grande passion’

https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12434/5b33ce52

D2016 grande passion … lidenskab [passion]

T2011 ཁོ་རང་བུད་མེད་དེ་ལ་ཡིད་སེམས་དབང་མེད་དུ་ཤོར་བས་བུད་མེད་དེས་ཁོ་ལ་དེ་ལས་ལྷག་པའི་བརྩེ་དང་འབྱིན་ངེས་ཡིན་པའི་ཐ་ཚིག་བསྒྲགས་པ་སོགས་གསལ་བོར་བཤད། [{kho rang bud med de la yid sems dbang med du shor bas bud med des kho la de las lhag pa'i brtse dang 'byin nges yin pa'i tha tshig bsgrags pa sogs gsal bor bshad} When he felt lost and powerless with attraction {yid sems} to this woman, she had given him assurances of an even stronger feeling]

Pe2010

آقای راچستر به او «کششی پرشور» داشت. سلین هم می گفت همین کشش را به آقای راچستر داشته

[{āqāy-i rāchester bi ū kishish-i pur-shūr dāsht. Selīn ham mīguft hamīn kishish rā bi āqāy-i rāchester dāshta} Mr Rochester had an excited attraction to her. Selin said too she had the same attraction to Mr Rochester]

He2007 … תשוקה גדולה[{teshuka gedola} a large/great desire … {no second rendition of ‘passion’}]

He1986 תשוקה לוהטת … תשוקה דומה [{teshuka lohetet} a fiery/burning desire … {teshuka doma} a similar desire]

It1974 quella che chiamava une grande passion. Céline aveva mostrato di ricambiarla in modo anche più intenso [what he called a grande passion. Céline had made a show of returning it even more intensely]

Sl1970 passion … strast [passion/lust]

Sp1941 que fue su gran pasión. Céline le había asegurado corresponderle con más ardor aún [who was his great passion. Céline had assured him that she responded with even greater ardour]

Por1951 Varens, por quem se apaixonara doidamente, paixão que, ostensivamente, ela retribuía [Varens, with whom he fell madly in love, a passion that she ostensibly requited]

R1950 une grande passion [пылкую страсть (фр.)]. На эту страсть [{pylkuiu strast’ (fr.)]. Na etu strast’} gloss: ardent passion. To this passion…]

He1946 רחשי תשוקה עזה … תשוקה [{rachashei teshuka ‘aza … teshuka} feelings of strong desire … desire]

R1901 [cut]

… Céline Varens; towards whom he had once cherished what he called a ‘grande passion.’ This passion Celine had professed to return with even superior ardour.

R1849 une grande passion, … эту страсть [{etu strast’} this passion]

It1904 quella che chiamava una gran passione. / Celina aveva finto di corrispondervi con un amore anche più ardente [what he called a great passion. Celina had pretended to respond to it with a love that was even more ardent]

Sp1947 lo que él llamaba une grande passion, a cuya pasión parecía ella corresponder aún con más entusiasmo [what he called a grande passion, to which passion she seemed to respond with even more enthusiasm]

It1951 ciò che chiamava una grande passion. A questa passione Céline aveva finto di corrispondere … [what he called a grande passion. This passion Céline had pretended to return]

Sl1955 strast … strast [passion/lust]

D1957 forelsket i [in love with] … forelskelse [love/romance]

A1985 »كان يشعر نحوها في يوم من الأيام بما سماه «حبّا عارما [{kāna yashʿur naḥwaha fī yawm min al ayām bimā sammāhu “ḥubban ʿariman”} he had felt for her, one of those days, what he called “an all-encompassing love”]

R1999 une grande passion … даже еще более пылкой взаимностью [{dazhe eshche bolee pylkoĭ vzaimnost’iu} reciprocate even more ardently]

Sp2009 lo que él calificó como una grande passion. Pasión que, al parecer, devoraba a la citada Céline con más ardor aún si cabe [what he described as a grande passion. Passion which, it seemed, devoured the aforementioned Céline with even more ardour, if that were possible]

It2014 quella che definì una grande passion. Passione che Céline aveva giurato di ricambiare con intensità perfino superiore alla sua [what he defined as a grande passion. A passion which Cèline had sworn she returned with an intensity even greater than his]

D2015 grande passion … passion

Judgment Would Warn Passion

Chapter 15, which begins with Mr Rochester’s confession about Céline, and continues with a description of Jane’s growing attachment to him, culminates with his bed being set on fire, Jane dousing the flames, and his suggestively tender goodnight to her. After which, she cannot sleep:

Till morning dawned I was tossed on a buoyant but unquiet sea, where billows of trouble rolled under surges of joy. I thought sometimes I saw beyond its wild waters a shore, sweet as the hills of Beulah; and now and then a freshening gale, wakened by hope, bore my spirit triumphantly towards the bourne: but I could not reach it, even in fancy — a counteracting breeze blew off land, and continually drove me back. Sense would resist delirium: judgment would warn passion. Too feverish to rest, I rose as soon as day dawned.

This was the end of Volume I in the first edition.

How does ‘passion’ here relate to Mr Rochester’s ‘passion’ for Céline? One clue is that Jane’s watery waking dream echoes comments made earlier in the chapter by Mr Rochester, when he said that one day she too would feel love as he did for Céline:

… you will come some day to a craggy pass in the channel, where the whole of life’s stream will be broken up into whirl and tumult, foam and noise: either you will be dashed to atoms on crag points, or lifted up and borne on by some master-wave into a calmer current — as I am now.

That enigmatic last clause — ‘as I am now’ — is not remarked on by the narrative. So, at the end of the chapter, Jane is experiencing a mixture of Rochester’s ‘tumult’ and ‘calmer current’, something that might perhaps be defined as a combination of passion and love. On this reading, ‘billows of trouble’ would be on the side of ‘passion’, while the ‘freshening gale, wakened by hope’ that bears Jane towards a shore ‘sweet as the hills of Beulah’ would be on the more virtuous side of ‘love’ (Beulah is associated with matrimony in the Biblical book of Isaiah and Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress).

However, when we try to connect Jane’s allegory of her feelings to the explanation she gives of them, the picture becomes more complicated. On the most plausible construal of the grammar, it is the virtuous-seeming gale that strikes her as ‘delirium’, and as ‘passion’, while ‘sense’ and ‘judgment’ are figured as the ‘counteracting breeze’ that keeps her from the happy shore. Here we can see the entangled nature of Jane’s situation, even before it is revealed that Rochester is married, and the corresponding emotional and ideological complexity of the novel, in which the longing for a happy marriage can figure as a dangerous temptation.

These contradictions play out variously in the translations. Some (e.g., Danish and Korean) use the same word for passion here as for Rochester’s ‘grande passion’; others use a different one (e.g., al-Baʿalbakī’s Arabic, A1985, and Ben Dov’s Hebrew, H1946). In Preminger’s 2007 Hebrew translation, as Adriana X. Jacobs comments, ‘what is interesting is actually the translation for “warn” — “מרסן”, “merasen”, to bridle, to restrain. This suggests that Preminger reads this primarily as a physical, sexual passion. Also, this language connects to the image of “reason [holding] the reins” in the next example (Chapter 19)’. In other translations too, what judgment does to passion varies as the relationship between the two terms is re-imagined by different minds in different languages: in the animation and array that follow, you will see verbs that can be back-translated as ‘cool’, ‘stand up to’, ‘push back’ and ‘resist’.

For the anonymous 1904 Italian translator, on the other hand, the significance of the contrasting winds switches round: here, it is delirium that conquers judgment, and passion that conquers wisdom, both of them pushing Jane back from the sweet, safe shore. It is possible that this translator felt the pressure of a famous Petrarch sonnet about a storm of desire, ‘Passa la nave mia colma d’oblio’, in which both ‘arte’ (skill) and ragione (‘reason’) die beneath the waves.8 As Charlotte Brontë may well have known the almost equally famous English version of the Petrarch by Thomas Wyatt (‘My galy charged with forgetfulnes’),9 perhaps what we are seeing here are a writer and a translator responding differently to a shared Anglo-Italian cultural inheritance.10

Animation 4: judgment would warn passion

https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12434/266540ab

It2014 La ragione si opponeva al delirio, e il senno ammoniva la passione [Reason stood in the way of delirium, and good sense admonished passion]

H2007 תשוקה [{teshuka} desire]

Pe1991 عقل در برابر جنون مقاومت میکرد تقدیر به هوس هشدار میداد [ʿaql dar barābar-i junūn muqāvimat mīkard, taqdīr bi havas hushdār mīdād reason resisted madness; fate warned desire]

H1986 כוח השיפוט הזהיר את ההתלהבות [{ko’ach ha-shiput hizir et ha-hitlavut} the force of judgment cautioned enthusiasm (also zeal, fervor, excitement)]

It1974 il giudizio respingeva la passione [judgement pushed passion back]

Sl1970 strast [passion]

It1951 Il buon senso voleva resistere al delirio, la saggezza opporsi alla passione [good sense tried to resist delirium, wisdom to stand up to passion]

H1946 שיפוט השכל — מתרה בגיאות הרגש [{shiput ha-sekhel — matre be-ge’a’ot ha-regesh} good judgement warns the tides of emotion]

R1901 [cut]

Sense would resist delirium: judgment would warn passion

R1849 passage abridged to: Усталая и вполнѣ измученная этими лихорадочными грёзами [{Ustalaya i vpolne izmuchennaia ėtimi likhoradochnymi grëzami} Tired and quite exhausted by these delirious dreams]

It1904 Invano il buon senso voleva resistere al delirio; la saggezza alla passione! [In vain good sense tried to resist delirium, and wisdom to resist passion]

R1950 Здравый смысл противостоял бреду, рассудок охлаждал страстные порывы [{Zdravyĭ smysl protivostoial bredu, rassudok okhlazhdal strastnye poryvy} Reason opposed delirium, judgement cooled passionate urges]

Sl1955 strasti [passions]

D1957 lidenskaben [passion] — Also in D2016R (lidenskab) and D2016P

A1985 .كان العقل يقاوم الهذيان وكانت الحكمة تكبح الهوى [{kāna al ʿaql yuqāwim al hadhayān wa kānat al ḥikma takbaḥ al hawā} Reason would/was resist(ing) delirium and wisdom/(common)sense, and would/was curtail(ing)/inhibit(ing)/contain(ing) passion/love]

R1999 Здравый смысл восставал против упоения, рассудок остерегал страсть [{Zdravyĭ smysl vosstaval protiv upoeniia, rassudok osteregal strast’} Reason revolted against intoxication, judgement warned against passion]

K2004 정열[{jung yul} passion]

T2011 passage abridged to: ང་སླར་རང་ཉིད་ཀྱི་མལ་ཁྲིའི་སྟེང་ཉལ་མོད་ཡེ་ནས་མ་ཁུགས་པར་དགའ་སྤྲོས་དང་སེམས་ཁྲལ་གཉིས་ཀྱི་འགལ་དུའི་ཁྲོད་ནམ་གསལ་རག་བར་ཏུ་གཡོ་འཁྱོམ་བྱས་སོང། [{nga slar rang nyid kyi mal khri'i steng nyal mod ye nas ma khugs par dga' spros dang sems khral gnyis kyi 'gal du'i khrod nam gsal rag bar tu g.yo 'khyom byas song/} I laid down again in my own bed, but I never fell asleep. I was swayed strongly back and forth between opposite extremes of excitement and worry]

The Passions May Rage Furiously

This passage comes near the end of the strange scene, in Chapter 19, where Rochester is disguised as a gypsy and pretends to tell Jane’s fortune. He has probed her feelings for him, and betrayed something of his feelings for her; now he ventriloquizes the traits that he sees in her face:

The forehead declares, “Reason sits firm and holds the reins, and she will not let the feelings burst away and hurry her to wild chasms. The passions may rage furiously, like true heathens, as they are; and the desires may imagine all sorts of vain things: but judgment shall still have the last word in every argument, and the casting vote in every decision.”

Rochester must feel these words as a challenge to his own behaviour and intentions, for a few moments after uttering them he cannot keep up the gipsy disguise, and throws it off.

Here we see ‘passions’ in the plural rather than the singular ‘passion’ that we have been exploring hitherto. These ‘passions’ seem to have a narrower range than the singular word, and the way they appear in Rochester’s discourse defines them quite precisely: they are a subset of ‘feelings’, and are distinguished from ‘desires’. We can infer that feelings such as rage and resentment would be ‘passions’, while love and attraction would be ‘desires’. ‘Heathens’ — to whom Rochester likens the passions — have appeared once before in the novel, near the start of the chapters at Lowood school, in a scene that echoes here. The angry young Jane protested to the saintly Helen Burns: ‘I must dislike those who, whatever I do to please them, persist in disliking me; I must resist those who punish me unjustly’; and Helen replied: ‘Heathens and savage tribes hold that doctrine, but Christians and civilised nations disown it’. No doubt Helen would approve of the discipline of the psyche that Rochester ascribes to Jane’s forehead, but the whole course of the novel (together with the range of uses of ‘passion’) suggests a more complex definition of virtue, one more open to resistance and rage.

In the translations, ‘passions’ is occasionally translated with a different word from the earlier appearances of ‘passion’, for instance al-Baʿalbakī’s 1985 Arabic translation: ‘الأهواء [whims {al ahwaa}]’. But much more often the same word is used — for instance, Italian ‘passioni’, Russian ‘страсти’ or Slovenian ‘strasti’. In Emilia Dobrzańska’s 1880 Polish translation, a gendered dynamic emerges, as Kasia Szymanska explains: ‘rozum’ [reason] — here singular — is masculine, while ‘namiętność’ [passion] is feminine, and the word for ‘heathen’, ‘poganka’ is also given in the feminine form. Rochester ‘is personifying passion by comparing it to a female heathen (individual)’, in contrast to ‘the masculine reason’. Reason and passion continue, of course, to be gendered in the later Polish translations, though the contrast becomes less stark when passions and heathens are pluralised.

Here, as in our previous example from Chapter 15, the prismatic potential of the scene can sometimes emerge more from the words connected to ‘passion’ than from ‘passion’ itself. In Portuguese, as Ana Teresa dos Santos points out, there is fascinating variation in the translation of the word ‘heathens’: by ‘Mècia’ (Por1941) as ‘bacantes’ (Bacchantes), suggesting wild revelry; by Cabral do Nascimento (Por1975) as ‘bárbaros’ (barbarians), suggesting rejection by society; by Goettems (Por2010) as ‘selvagens’ (wild things/animals); and by Rocha (Por2011) as ‘idolaters’, connecting Jane’s love for Rochester to idolatry.

This sequence of words, with its emotional extremity, also leaves its mark on the translations in another way: by being cut, from several of them — as you will see in the animation and array below. The anonymous Russian translation of 1901, the 1921 Polish translation by Zofia Sawicka and the 1957 Danish translation by Aslaug Mikkelsen were all abridged (and the first two were aimed squarely at younger readers), so they omit other parts of the novel as well. But it is striking that this passage is one that they all think needs to be excluded.11

Animation 5: The passions may rage furiously

https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12434/65df9373

It2014 Le passioni possono scatenarsi con la furia barbarica che è loro propria [the passions can run wild, with the barbaric fury that is proper to them]

Por2010 As paixões podem rugir furiosamente, como verdadeiras selvagens que são [the passions may roar furiously, like the true wild things that they are]

Pol2009 Namiętności mogą się miotać, rozwścieczone, jak prawdziwi poganie [passions run amok, furious like true pagans]

A1985.ان الأهواء قد تثور على نحو ضار كما يثور الوثنيون الحقيقيون [{inna al ahwāʾ (sing. hawā) qadd tathūr ʿalā naḥw ḍār kamā yathūr al wathaniyyūn al ḥaqīqiyyūn} Indeed [the] whims may revolt/rage uncontrollably, like true pagans]

It1974 Le passioni possono infuriare con la violenza pagana loro propria [the passions may flare up with their proper (own) pagan violence]

Sl1955 strasti [passions]

R1950 & 1999 страсти [{strasti} passions]

Pol1930 Niech sobie namiętności, pogańskie plemię szaleją wściekle [passions, a pagan tribe, rage furiously]

It1904 La passione potrà urlare furiosamente, da vera pagana com’è [passion may howl furiously, like the true pagan that she is]

Pol1880 namiętność, jako prawdziwa poganka [passion, like a true heathen]

The passions may rage furiously, like true heathens, as they are

R1849 Пусть бушуютъ страсти [{Pust’ bushuиut” strasti} let passions rage]

R1901 [cut]

Pol1921 [cut]

Por1941 As paixões podem desencadear-se, furiosas como bacantes [the passions may thrive, furious like bacchantes] — using Roman mythology to associate “passion” and revelry, frenzy, lack of control, and rage

It1951 La passione potrà scatenarsi furiosamente, da vera pagana com’è [passion may run wild furiously, like the true pagan that she is]

D1957 [cut]

Por1975 Podem as paixões bramar furiosamente, como verdadeiros bárbaros, que são [the passions may yell furiously, like true barbarians, as they are]

K2004 감정[{gam jung} emotion]

Pe2010 شور و سودا [{shūr va sowdā} Excitement and melancholy]

Por2011: As paixões bem podem grassar desvairadamente, como os autênticos idólatras que de facto são [the passions may disseminate in a wild manner, like the true idolaters that they are]

D2015&16 lidenskaberne [passions]

A Solemn Passion Is Conceived in my Heart

Now we are in the complex, emotionally harrowing Chapter 27, which follows the collapse of the wedding and the revelation of Bertha. Mr Rochester narrates the story of his marriage and reaffirms his love for Jane:

After a youth and manhood, passed half in unutterable misery and half in dreary solitude, I have for the first time found what I can truly love — I have found you. You are my sympathy — my better self — my good angel — I am bound to you with a strong attachment. I think you good, gifted, lovely: a fervent, a solemn passion is conceived in my heart; it leans to you, draws you to my centre and spring of life, wraps my existence about you, and, kindling in pure, powerful flame, fuses you and me in one.

Jane accepts that this is true love (‘not a human being that ever lived could wish to be loved better than I was loved’), and forgives Rochester for his deception of her; and yet she is clear that she cannot stay with him, and leaves Thornfield in agony of heart.

This is the consummation of all the uses of ‘passion’ hitherto: here, ‘passion’ appears in its most positive light, as a power leading to good, yet it is also connected to the darker senses (suffering, anger, stubbornness) that have appeared in our earlier examples. Rochester’s phrasing (‘a fervent, a solemn … conceived in my heart’) pushes those other connotations away (this is the good kind of passion, he wants to assert); and yet, in doing so, he cannot but acknowledge that they exist.

In the translations into European languages, similar phrasing is used to similar effect: as you can see below, the Italian and Russian translations reveal the ‘shadow texts’, the cluster of related words, that hover around Rochester’s adjectives ‘fervent’ and ‘solemn’ and feed into their signification even though they are not visibly written in the English. The Arabic and Persian translations, in contrast, both reach for different nouns than those that have been used for our earlier instances of ‘passion’, continuing their work of rendering Brontë’s word into a varied vocabulary. As Kayvan Tahmasebian comments, the Persian word ‘hāl’, used by Reza Reza’i (Pe2010), ‘has a wide range of meanings. Primarily, it denotes the present time. It is also used in reference to one’s own state, how one feels. Its other meanings are “adventure”, “great pleasure”, “jouissance”.’ Those kinds of intensity all feel appropriate here.12

Animation 6: a solemn passion is conceived in my heart

https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12434/e70765ab

D2015&16 lidenskab [passion]

T2011 [cut]

K2004 정열 [{jung yul} passion]

A1985 .إن فؤادي ليضمر لك عاطفة مهيبة متقدة [{inna fuādī la yuḍmira laka ʿātifa mahība muttaqida} Indeed it is my heart that holds/keeps/preserves burning, majestic passion for you]

Sl1955 & 1970 strast [passion]

R1950 живет благоговейная и глубокая страсть [{zhivet blagogoveĭnaia i glubokaia strast’} lives passion characterised by awe and depth]

R1901 [cut]

a fervent, a solemn passion is conceived in my heart

R1849 Пылкая и торжественная страсть [{Pylkaia i torzhestvennaia strast’} Fervent and solemn passion]

It1904 ho concepito nel cuore una passione solenne e fervente [I have conceived a solemn, fervent passion in my heart]

It1951 il mio cuore ha concepito una passione grave e fervida [my heart has conceived a solemn, vivid passion]

It1974 c’è nel mio cuore una passione fervida e viva [in my heart there is a fervent, lively passion]

R1999 Жаркая благороднейшая любовь [{Zharkaia blagorodneĭshaia liubov’} Ardent, most noble love]

Pe2010 شور و حال [{shūr va hāl} excitement and ecstasy]

It2014 nel mio cuore c’è una passione grande e fervida [in my heart there is a great and fervent passion]

Works Cited

For the translations of Jane Eyre referred to, please see the List of Translations at the end of this book.

Cozzo, Giuseppe Salvo, ed., Le Rime di Francesco Petrarca (Florence: G. C. Sansoni, 1904).

Muir, Kenneth and Patricia Thomson, eds., Collected Poems of Thomas Wyatt (Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 1969).

Proquest Literature Online, https://www.proquest.com/lion

1 As ever, all publication details for the translations quoted can be found in the List of Translations at the end of this volume. The abbreviations used here, and throughout the animations and static arrays that follow, start with an indicator of the language (F = French), followed by the year of first publication, and then — if there is more than one translation into that language for that year — the first letter of the translator’s name.

2 In James Fenimore Cooper’s Home as Found (Philadelphia: Lea and Blanchard, 1838), Proquest Literature Online, https://www.proquest.com/lion.

3 John Cayley, Programmatology, https://programmatology.shadoof.net/index.php, accessed 6th November, 2021.

4 This animation and array incorporate research by Eugenia Kelbert, Céline Sabiron, Ana Teresa Marques dos Santos, Andrés Claro, Paola Gaudio, Adriana X. Jacobs, Sowon S. Park, Matthew Reynolds, Yousif M. Qasmiyeh, and Jernej Habjan.

5 This animation and array incorporate research by Eugenia Kelbert, Yousif M. Qasmiyeh, Jernej Habjan, Ida Klitgård, Ulrich Timme Kragh, Sowon S. Park, Matthew Reynolds, and Kayvan Tahmasebian.

6 The Letters of Charlotte Brontë, 2 vols, ed. Margaret Smith (Oxford, Clarendon Press, 1995–2000), i, p. 233. Online: Intelex Past Masters Full Text Humanities.

7 This animation and array incorporate research by Eugenia Kelbert, Céline Sabiron, Ana Teresa Marques dos Santos, Andrés Claro, Adriana X. Jacobs, Matthew Reynolds, Yousif M. Qasmiyeh, Jernej Habjan, Ida Klitgård, Kayvan Tahmasebian, and Ulrich Timme Kragh.

8 Le Rime di Francesco Petrarca, ed. Giuseppe Salvo Cozzo (Florence: G. C. Sansoni, 1904), p. 189.

9 Collected Poems of Thomas Wyatt, eds Kenneth Muir and Patricia Thomson (Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 1969), pp. 21–22.

10 This animation and array incorporate research by Eugenia Kelbert, Adriana X. Jacobs, Yousif M. Qasmiyeh, Jernej Habjan, Ida Klitgård, Ulrich Timme Kragh, Sowon S. Park, Matthew Reynolds, and Kayvan Tahmasebian.

11 This animation and array incorporate research by Eugenia Kelbert, Ana Teresa Marques dos Santos, Sowon S. Park, Kasia Szymanska, Matthew Reynolds, Yousif M. Qasmiyeh, Jernej Habjan, Kayvan Tahmasebian, and Ida Klitgård.

12 This animation and array incorporate research by Eugenia Kelbert, Kayvan Tahmasebian, Ida Klitgård, Ulrich Timme Kragh, Sowon S. Park, Matthew Reynolds, Yousif M. Qasmiyeh, Jernej Habjan.