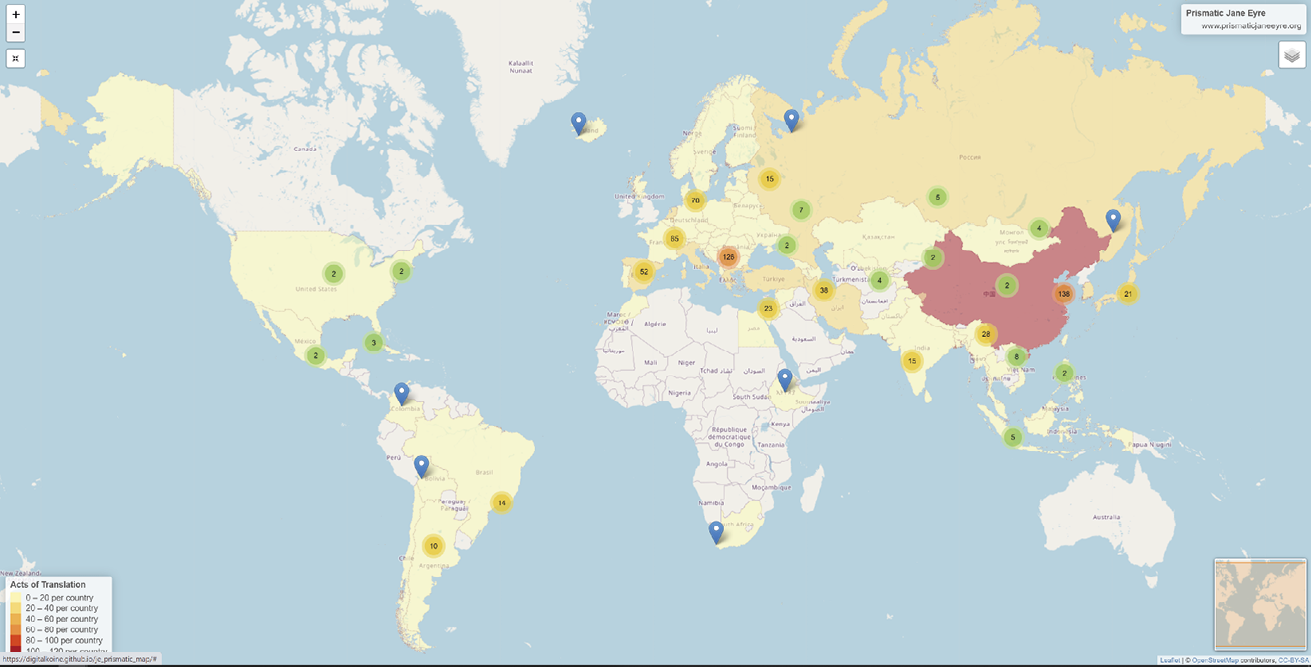

The World Map https://digitalkoine.github.io/je_prismatic_map Created by Giovanni Pietro Vitali; maps © Thunderforest, data © OpenStreetMap contributors

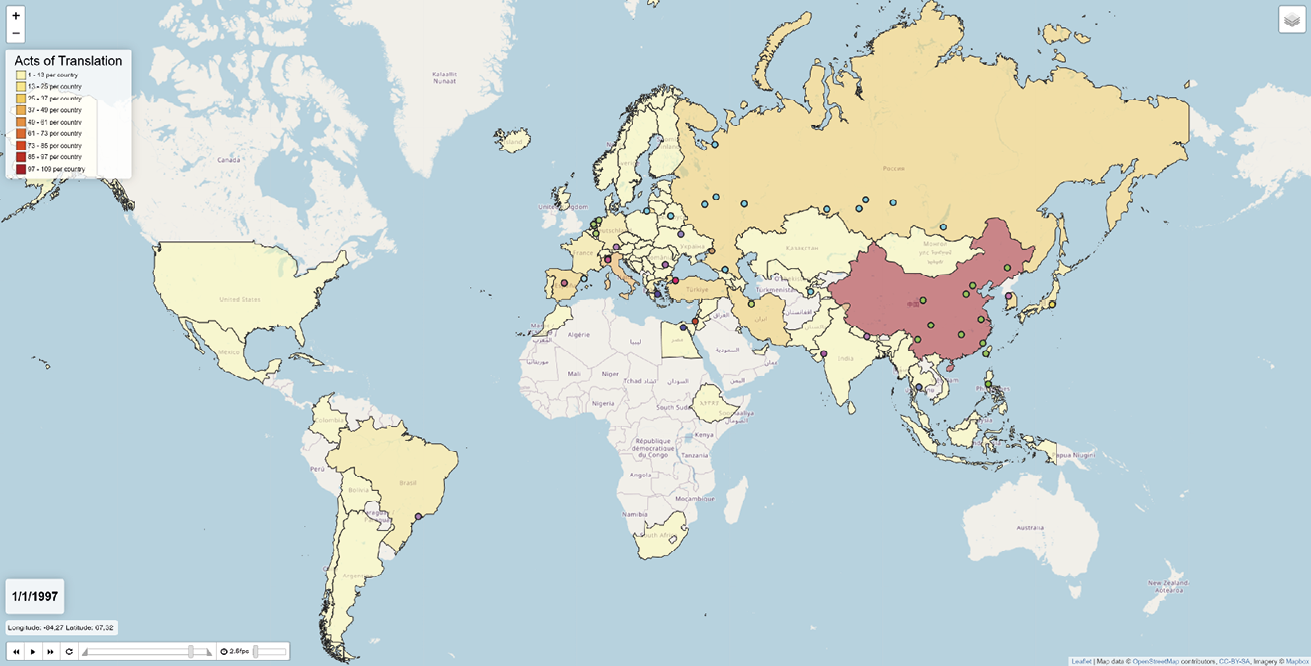

The Time Map https://digitalkoine.github.io/translations_timemap Created by Giovanni Pietro Vitali and Simone Landucci;© OpenStreetMap contributors, © Mapbox

VI. ‘Plain’ through Language(s)

© 2023 Matthew Reynolds, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0319.18

The word ‘plain’, with its derivatives ‘plainly’ and ‘plainness’, appears in the novel 48 times. As we saw in Chapter IV, it covers a wide semantic range: in this, it is like ‘passion’ (which we explored in Chapter V), only the spread of meanings and suggestions is even more expansive. ‘Plain’ can refer to physical looks — Jane is frequently called ‘plain’, by herself and others — and to dress, hairstyle and food: plain uniforms and ‘plain fare’ form part of the grim regime at Lowood School. But it is also, crucially, used of perception and speech, and especially so as they are performed by Jane: she sees and hears things plainly, and speaks ‘the plain truth’. Her behaviour in the book shares these traits with the narrative that she is imagined as having written: when the second edition of Jane Eyre came out in 1848, Brontë described it in the ‘Preface’ as ‘a plain tale’.

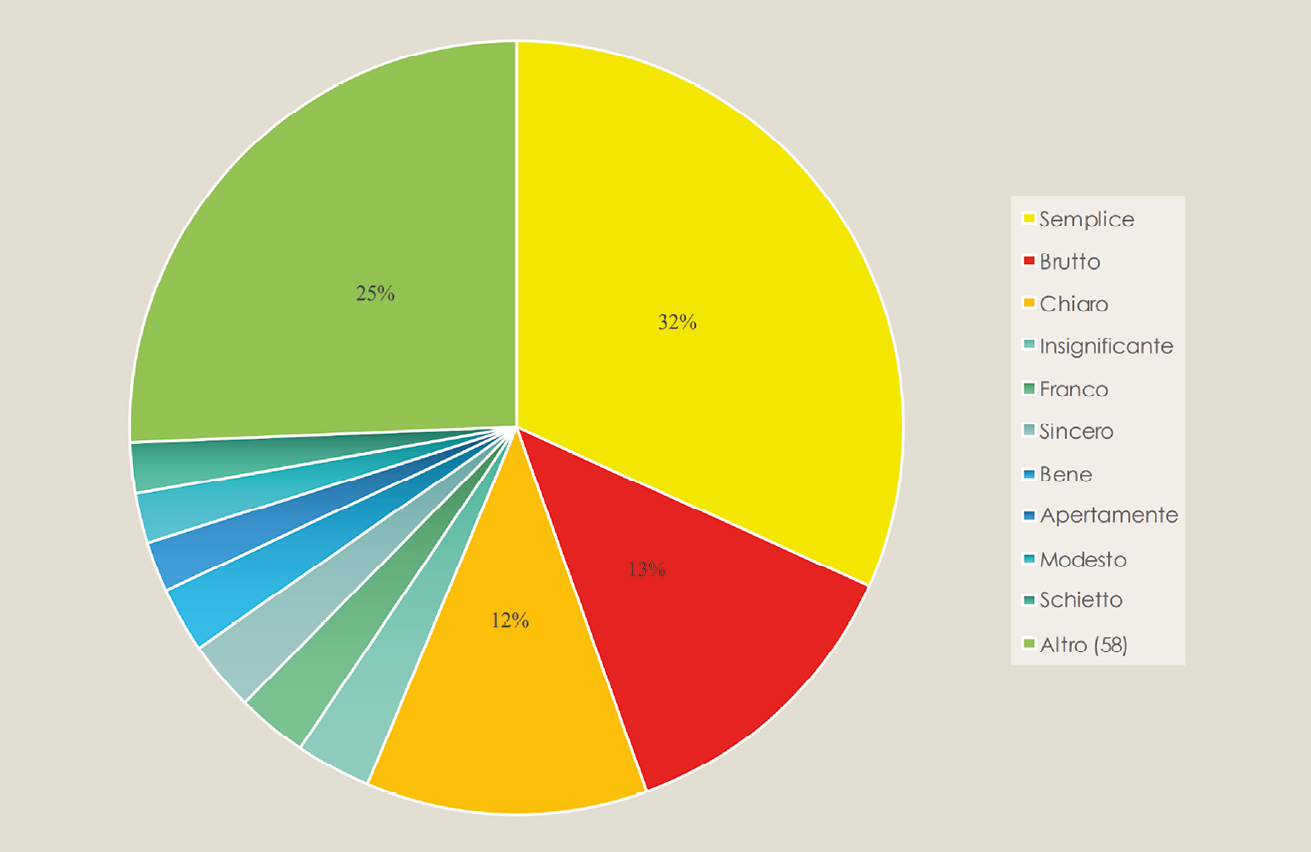

Again, as with ‘passion’, the reiterations of ‘plain’ in the English text imply an argument about values. To put it briefly: it does not matter if a woman looks plain; what is important is that she perceives things plainly (i.e., gets at the truth) and utters them plainly, whether she is speaking to Mr Rochester or writing for the public. As we will see in more detail below, no one word in any translation covers the same range as Brontë’s ‘plain’ (though the Slovenian ‘preprosto’ comes close). Indeed, research by Caterina Cappelli has shown that, in thirteen Italian translations of Jane Eyre, ‘plain’ is translated by a total of 68 separate terms (see figures 21 and 22 for details), and there are also about 60 occasions on which no equivalent is provided for the word. So, when it comes to lexical patterning, none of the translations makes exactly the same connections as the source text.

Fig. 21 Translations of ‘plain’ and its derivatives in 13 Italian translations, researched and created by Caterina Cappelli

Fig. 22 A prismatic visualization of the data presented in Figure 21, researched and created by Caterina Cappelli

But the argument about plainness is not made only through particular vocabulary. It is also made through the plot, the sequence of events in which the novel’s valuations are acted out by its protagonists. In this dramatic unfolding of meaning, Jane’s looks and language are still, broadly speaking, ‘plain’, whatever words are used to describe them. So when we study the source text and the translations together we can see, in the English, the particular lexical texture that helped Brontë develop her powerful understanding of the significance of plainness; and then, in the translations, an explosion of re-wordings, through which the nuances of that understanding shift as it is re-formed with different linguistic materials. What in English is the plain truth may be described with words that can be back-translated as ‘naked’, ‘simple’ or ‘unadorned’ (and many more), while plain speech might be seen as ‘hasty’, ‘blunt’ or ‘open’. These re-wordings then establish new connections across the texts and contexts in which they appear. For instance — as we will see — where Brontë’s English maintains a distinction between ‘plain’ and ‘ugly’, several French and Italian translations use just one word (‘laid’ or ‘brutto’) to span both English terms.

In Brontë’s text, ‘plain’ establishes various fleeting and perhaps accidental relationships with other words to which it is connected by phonetics and/or etymology. It rhymes with ‘pain’ and has a kinship to ‘explain’. It overlaps with its homonyms ‘to plain’ — that is, to lament, as when, in Chapter 28, Jane’s heart ‘plained of its gaping wounds’ — and ‘a plain’ in the sense of a flat stretch of landscape, as when, in Chapter 24, Mr Rochester plans to take Jane to ‘Italian plains’ after the wedding. And of course it rhymes with the protagonist’s own name. The phrase ‘plain Jane’ never exactly appears in the novel (a database search suggests that it first appeared in print in a play by M. Rophino Lacy, Doing for the Best, which premièred in 1861, and which has some thematic similarities to Jane Eyre, though no explicit indebtedness).1 Nevertheless, ‘plain’ is at the heart of Jane’s being, and her book charges the word with new energies.

In the translations, the linguistic phosphorescence of rhyme of course plays out differently, across other words. But the feminist thrust of Jane’s association with plainness — in all its meanings — does not therefore lose its force, as essays by Andrés Claro, Maria Claudia Pazos Alonso and Ana Teresa Marques dos Santos and others in this volume have already shown. Jane may no longer rhyme with ‘plain’, but — in the eyes of many translators — her tale still speaks plain truths.

The Plain Truth

Our first prismatic expansion of the word ‘plain’ is from Chapter 12, not long after Jane’s arrival at Thornfield Hall. She has already got used to her new situation, and is even a little bored of it: often, she climbs to the roof and longs to see beyond the horizon to the ‘busy world’, or walks back and forth along the corridor of the ‘third story’, in which storied realm she opens her ‘inward ear to a tale that was never ended — a tale my imagination created, and narrated continuously; quickened with all of incident, life, fire, feeling, that I desired and had not in my actual existence’.2 Here too she makes the feminist declaration that would inspire many readers of the novel and its translations: ‘women are supposed to be very calm generally: but women feel just as men feel; they need exercise for their faculties, and a field for their efforts as much as their brothers do; they suffer from too rigid a restraint, too absolute a stagnation, precisely as men would suffer ….’

The sentence that is our focus joins this play of tensions between lived stagnation and the freedom that is imagined and desired. For, while she is alone and occupied with such thoughts, Jane ‘not unfrequently’ hears the laugh that she thinks to be Grace Poole’s: ‘the same peal, the same low, slow ha! ha! which, when first heard, had thrilled me: I heard too her eccentric murmurs, stranger than her laugh’. These fascinating sounds contrast with what Jane sees of Grace, and it is this that calls out the word ‘plain’:

she would come out of her room with a basin, or a plate, or a tray in her hand, go down to the kitchen and shortly return, generally (oh, romantic reader, forgive me for telling the plain truth!) bearing a pot of porter. Her appearance always acted as a damper to the curiosity raised by her oral oddities: hard-featured and staid, she had no point to which interest could attach.

The wishes of the imagined romantic reader align with Jane’s: both hope for more excitement than Thornfield currently provides. The word ‘plain’ seems to describe the way things are — not eventful enough to satisfy Jane’s desires (earlier in the chapter the same has been said of Adèle and Mrs Fairfax). Yet there is also a counter-current in the word, for as the novel proceeds it will turn out that the plain truth about Grace Poole’s liking for porter (a black beer) is not the whole truth about the thrilling laugh. There is a hint of this in the address to the reader, which has a knowingness about it, given that what is being read is a novel in which some elements of romance are likely to appear. If readers forgive the narrator for telling the plain truth here, it may be because they are pretty sure that Jane’s wish will come true, and greater excitements soon appear.

As you can see in the animation and array below, three of the earliest translations skip the whole address to the reader: the feeling seems to be that Jane’s chatty, almost flirtatious relationship with her imagined reader is superfluous, perhaps disconcerting, and can happily be left out. In Elvira Rosa’s 1925 Italian version, on the other hand, the phrase ‘romantic reader’ is itself romanticised, to become ‘anime romantiche’ (‘romantic souls’): this is in line with the generally sentimental tendency of her translation.

Some translators find in their languages words that approximate quite closely to ‘plain’: ‘escueta’ (María Fernanda Peredá, Sp1947); ‘schietta’ (G. Pozzo Galeazzi, It1951); ‘preprosto’ (Borko and Dolenc, Sl1955); or ‘schlichte’ (Melanie Walz, Ge2015). Other translations turn the quality of the ‘truth’ in different directions, such as ‘vsakdanjo’ (‘everyday’, Božena Legiša-Velikonja, Sl1970) or ‘пошлую’ (‘vulgar’, Irina Gurova, R1999); ‘desnuda’ or ‘nøgne’ (‘naked’, Juan G. de Luaces, Sp1943; Luise Hemmer Pihl, D2016); or ‘sin adornos’ or ‘usmyikkede’ (‘unadorned’, Toni Hill, Sp2009; Christian Rohde, D2015). When the plain truth is turned into a ‘détail’ or ‘particolare’ (Gilbert and Duvivier, Fr1919; Elvira Rosa, It1925) it takes on a scientific, almost forensic feel; but it can also — in contrast — assume a legal, or even religious tonality, as with ‘la vérité entière’ (‘the whole truth’, Noémie Lesbazeilles-Souvestre, F1954) or ‘la semplice verità’ (‘the simple truth’, Ugo Dèttore, It1974). All these variants have something in common, in that they can all be set in opposition to the genre of romance; but each one angles the binary slightly differently. What is at stake between the ‘romantic’ and the ‘plain’ can become a matter of adornment vs nakedness, complication vs simplicity, gentility vs vulgarity, or vagueness vs detail.3

Animation 7: the plain truth

https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12434/3360ced7

D2016 nøgne sandhed [naked truth]

Ge2015 der romantisch Leser vergebe mir, dass ich die schlichte Wahrheit sage [forgive me, romantic reader, for telling the plain truth]

It2014 oh, mio romantico lettore, perdonami se dico la verità nuda e cruda! [oh, my romantic reader, forgive me if I speak the nude, raw truth]

Hi2002 <parenthesis deleted>

Ge1979 romantischer Leser, verzeih mir, wenn ich die Wahrheit sage [romantic reader, forgive me, if I tell the truth]

Sl1970 povem tako vsakdanjo stvar [talk of such everyday things]

E1959 oo, romantiline lugeja, andesta, et karmi tõtt kõnelen [oh, romantic reader, forgive me for telling the harsh truth]

It1951 tu, romantico lettore, perdonami se dico la schietta verità [you, romantic reader, forgive me if I speak the plain truth]

Sp1947 perdona, lector romántico, que te diga la verdad escueta [forgive me, romantic reader, that I tell you the plain truth]

Sp1943 perdona, lector romántico, que te diga la verdad desnuda [forgive me, romantic reader, that I tell you the naked truth]

F1919 ce détail [this detail]

R1901 <parenthesis deleted>

F1854 la vérité entière [the whole truth]

generally (oh, romantic reader, forgive me for telling the plain truth!) bearing a pot of porter

R1849 <parenthesis deleted>

Ge1888 oh, verzeihe mir, romantische Leserin, wenn ich die Wahrheit sage [oh, forgive me, romantic woman reader, if I tell the truth]

It1904 <parenthesis deleted>

It1925 perdonatemi questo particolare, anime romantiche [forgive me this particular, romantic souls]

F1946, 1946B, 2008 la simple vérité [the simple truth]

R1950 прости мне эту грубую правду, романтический читатель [forgive me this rough truth, romantic reader]

Sl1955 razodenem preprosto resnico [reveal the plain truth]

F1966 la vérité toute nue [the wholly naked truth]

It1974 oh! romantico lettore, perdonami se dico la semplice verità! [oh! romantic reader, forgive me if I speak the simple truth]

R1999 ах, романтичный читатель, прости меня за пошлую правду! [ach, romantic reader, forgive me the vulgar truth!]

Sp2009 oh, lector romántico, perdóname por contarte la verdad sin adornos [oh, romantic reader, forgive me for telling you the unadorned truth]

It2014S oh, romantico lettore, ti chiedo scusa, ma questa è la pura e semplice verità! [oh, romantic reader, I ask your pardon, but this is the pure and simple truth]

D2015 usmyikkede sandhed [unadorned truth]

Hear Plainly

Our next instance comes from later in the same chapter. Jane has taken the opportunity to get out of the house and carry a letter to the nearby village of Hay. Halfway there, she pauses on a stile and looks at the landscape around:

On the hill-top above me sat the rising moon; pale yet as a cloud, but brightening momently: she looked over Hay, which, half lost in trees, sent up a blue smoke from its few chimneys; it was yet a mile distant, but in the absolute hush I could hear plainly its thin murmurs of life.

This passage joins the interplay of sight and sound which we have observed earlier in the chapter, though with an opposite emphasis. There, ‘eccentric murmurs’ could not be explained by the ‘plain truth’ which presented itself to Jane’s eyes; but here ‘thin murmurs’ can be heard ‘plainly’, though their origin is distant and not wholly visible. And if, earlier, the ‘plain truth’ was in a flirtatious relationship with the desires of the ‘romantic reader’, appearing to deny excitements which nonetheless remained a possibility, here again a plain appearance seems connected to the energies of romance. For just as Jane’s ear is completing its audit of little, everyday sounds, something quite different breaks in: a ‘rude noise’ which — like the ‘third story’ and the thrilling laugh at Thornfield — sparks her imagination, this time summoning fairy tales and the folkloric figure of the Gytrash, and heralding the encounter with Mr Rochester.

The translations gathered here show how distinctive a feature of Brontë’s English it was that the same term could be used in both this and the earlier quotation, for the translators all have to reach for different words, generally shifting the quality of Jane’s hearing towards distinctness or clarity, though sometimes leaving it with no adverb at all. Several of them also reveal, by turning away from it, the insistence Brontë gives to Jane’s first-person, always liking her to be the subject of verbs, as she is here. Madli Kütt points out that Elvi Kippasto’s 1959 Estonian translation opts for an impersonal construction (part of a trend which she explores at length below in Essay 16); and the same move is made by several other translators.4

Animation 8: hear plainly

https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12434/613b7725

Ge2015 konnte ich die leisen Lebensregungen des Dorfes vernehmen [I could hear the soft movements of life in the village]

It2014 sentivo chiaramente il brusio di vita che di là si levava [I heard clearly the murmur of life that arose from there]

Hi2002 मैं उसके जीवन की मन्द ध्वनि स्पष्ट सुन रही थी [{maĩ uske jīvan kī mand dhvani spaṣṭa sun rahī thī } I was clearly hearing its low/soft sound]

Ge1979 konnte ich … das dünne Gemurmel seines Lebens vernehmen [I could hear … the thin murmur of its life]

Sl1970 razločno slišala [distinctly hear]

D1957, 2015, 2106 tydeligt [clearly]

It1951 ne distinguevo nitidamente i rumori [I clearly distinguished its sounds]

F1946B, 1964, 1966 distinctement [distinctly]

F1919 mon oreille distinguait, dans le silence absolu qui m’entourait, le murmure léger [my ear distinguished, in the absolute silence around me, the soft murmur]

R1901 я могла ясно различить тихій гулъ [I could distinctly make out a quiet din]

F1854 si clairs bien qu’éloignés [so clear though remote]

I could hear plainly its thin murmurs of life

R1849 я, однакожъ, ясно могла слышать смутный гулъ, обличавшій проявленіе жизни [I however could distinctly hear a vague rumble revealing the presence of life]

Ge1888 drangen die Töne des schwachen Lebens, welches in dem Ort pulsierte, bis zu mir herauf [the sounds of the thin faint life that throbbed in the place reached up to me]

It1904 distinguevo i rumori [I distinguished the sounds]

It1925 il mio orecchio distingueva … il mormorio leggero della vita urbana [my ear distinguished … the light murmur of urban life]

R1950 уже доносились ко мне несложные звуки ее жизни [unsophisticated/simple sounds of its life could already reach me]

Sl1955 natančno zaznati [clearly register]

E1959 kuid täielikus vaikuses oli kaugeid külaeluhääli selgesti kuulda [the faraway sounds of village life could be clearly heard]

It1974 potevo udire distintamente i lievi sussurri della sua vita [I could hear distinctly the soft whispers of its life]

R1999 до меня уже доносились легкие отголоски тамошней жизни [light echoes of life of over there already reached me]

Fr2008 nettement [clearly]

It2014S potevo percepire chiaramente i suoi tenui mormorii di vita [I could perceive clearly its faint murmurs of life]

Plain … Too Plain

In Chapter 14 there are successive appearances of ‘plain’; and as they are more tightly linked than those in Chapter 12 we will consider them together. First, Mr Rochester summons Adèle and Jane to join him after dinner:

I brushed Adèle’s hair and made her neat, and having ascertained that I was myself in my usual Quaker trim, where there was nothing to retouch — all being too close and plain, braided locks included, to admit of disarrangement — we descended.

Then, down in the dining room, after Mr Rochester has asked if Jane thinks him handsome and she has replied ‘no, sir’, Jane’s Quaker look, together with the idea of disarrangement, recurs in his speech to her. He says she has ‘the air of a little nonnette’ (a word, meaning ‘little nun’, that appears in French dictionaries and not in English ones — though, since Jane and Mr Rochester both mix French and English in their language use, it is not marked as foreign in the text); and he elaborates with words that echo the ‘qu’ of ‘Quaker’: ‘quaint, quiet, …’. But this reserved exterior conceals disruptive energies: ‘when one asks you a question … you rap out a round rejoinder, which, if not blunt, is at least brusque. What do you mean by it?’ In her reply, Jane reaches for the word ‘plain’:

‘Sir, I was too plain: I beg your pardon. I ought to have replied that it was not easy to give an impromptu answer to a question about appearances; that tastes differ; that beauty is of little consequence, or something of that sort.’

Rochester feels there to be a contrast between the modest look and assertive speech; but Jane conceives of both as manifesting the same quality: plainness, which eschews both ornament and circumlocution.

Just as with Chapter 12, none of the translators find it possible to use the same word for both these occurrences of ‘plain’. In some cases, their choices make Jane seem to share Rochester’s view, as when Aslaug Mikkelsen (D1957) presents Jane’s dress as ‘ordentlig’ (‘decent’), in contrast to her speaking ‘så ligeud’ (‘so bluntly’). In others, the English Jane’s idea comes through more fully: both Elvira Rosa (It1925) and Ugo Dèttore (It1974) see Jane’s dress as ‘simple’ (‘semplice’, possessing ‘semplicità’), while her speech is ‘sincere’ (‘sincera’). Though obviously not the same as exact repetition, this pairing does suggest a continuity of values.

Overall, these two new instances of ‘plain’ give yet more evidence of the enormous semantic productivity of Brontë’s repeated use of the word. Just occasionally you can find an equivalent that has appeared before: for instance, Dèttore (It1974) chooses ‘semplice’ both for Jane’s clothing here and for ‘the plain truth’ in Chapter 12, while Monica Pareschi (It2014) and Stella Sacchini (It2014S) both employ ‘schietta’ for Jane’s speech, a word that had also been used for ‘the plain truth’ by G. Pozzo Galeazzi in 1951. It is all the more striking that Pareschi and Sacchini both sought other terms for ‘the plain truth’, while Pozzo Galeazzi chooses a different word (‘franca’, ‘frank’) for Jane’s plain speech here.5

Animation 9: plain … too plain

https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12434/d4aae74d

D2016 enkelt … talte for ligefremt [simple/plain … put it too bluntly]

D2015 < Ø > … var for hurtig [was too quick]

It2014 era troppo essenziale e austero … ‘Signore, sono stata troppo schietta [it was too basic and austere … ‘Sir, I was too plain]

R1999 такой скромной простоте … — Сэр, я была слишком прямолинейна [such modest simplicity … ‘Sir, I was too direct]

It1974 tutto infatti era troppo semplice e raccolto … ‘Signore, sono stata troppo sincera [all indeed was too simple and gathered … ‘Sir, I was too sincere]

D1957 ordentlig … ‘… sagde min mening så ligeud [decent … ‘… spoke my opinion so bluntly]

R1950 < Ø > … — Сэр, я слишком поторопилась [‘Sir, I was too hasty]

It1904 in ordine … ‘Scusate, signore, se sono stata troppo franca [in order … ‘Excuse me, sir, if I was too frank]

Ge1888 alles zu fest und einfach und glatt … „Sir, ich war wohl zu deutlich [everything was too fixed and simple and smooth … ‘Sir, I may have been too clear]

all being too close and plain … ‘Sir, I was too plain

R1849 безукоризненной опрятности — Извините, сэръ: я была слишкомъ-откровенна [immaculate neatness … ‘Sorry, sir: I was too frank]

R1901 мой собственный простой нарядъ … < Ø > [my own simple outfit]

It1925 così austera nella sua semplicità … ‘… sono stata troppo sincera [so austere in its simplicity … ‘… I was too sincere]

It1951 la mia semplice veste e la liscia acconciatura … ‘Scusi, signore, sono stata troppo franca [my simple dress and smooth hairstyle … ‘Excuse me, sir, I was too frank]

E1959 kõik oli ülimalt lihtne ja range … ‘Palun vabandust, sir, ma olin liiga avameelne [everything was extremely simple and strict … ‘I beg your pardon, sir, I was too frank]

Ge1979 ordentlich aussah … »Ich war zu offen [looked tidy … ‘I was too open]

Hi2002 किसी परिवर्तन की या पुनः प्रसाधन की आवश्यकता नहीं है [{kisī parivartan kī yā punaḥ prasādhan kī āvaśyaktā nahĩ hai} no necessity for change or again dressing / toilet] … महाशय, मैं बेढब बोल गई। [{mahāśay, maĩ beḍhab bol gaī} Sir, I spoke ugly]

It2014S era tutto troppo composto e semplice … ‘Signore, sono stata troppo schietta [it was all too composed and simple … ‘Sir, I was too plain]

Ge2015 mein schlichtes, enganliegendes Kleid … »Sir, ich war zu offen [my simple, close-fitting dress … ‘Sir, I was too open]

Plain, Unvarnished … Poor, and Plain

After the nocturnal fire in Mr Rochester’s bed, which Jane puts out with a water jug, the pair share a tender moment holding hands. Jane is left ‘feverish’ with emotional confusion and passes a sleepless night. The next day is described in Chapter 16, which, in the first edition, was the start of the second volume. Jane longs to see Mr Rochester, but it turns out that he has gone to stay at another house, miles away, where a party of gentlefolk is assembled. Mrs Fairfax tells Jane of the beautiful young ladies who will be there, especially the much-admired Blanche Ingram, with whom Mr Rochester once sang a beautiful duet.

Later, alone, Jane takes a stern view of the ‘hopes, wishes, sentiments’ about Mr Rochester that had been budding inside her, and the word ‘plain’ pops up to express it:

Reason having come forward and told, in her own quiet way, a plain, unvarnished tale, showing how I had rejected the real and rabidly devoured the ideal; — I pronounced judgment to this effect: —

That a greater fool than Jane Eyre had never breathed the breath of life …

The judgment continues, getting fiercer and fiercer: ‘your folly sickens me … Poor stupid dupe! … Blind puppy!’ — and it culminates in punishment where ‘plain’ appears again:

‘Listen, then, Jane Eyre, to your sentence: to-morrow, place the glass before you, and draw in chalk your own picture, faithfully; without softening one defect: omit no harsh line, smooth away no displeasing irregularity; write under it, “Portrait of a Governess. Disconnected, poor, and plain.”’

(According to the Oxford English Dictionary, ‘disconnected’ means ‘without family connections of good social standing; not well connected’. You will see that other possible nuances emerge in the translations.) Jane is also to paint, as a contrast, a beautiful fantasy portrait on a piece of ivory, to represent Blanche Ingram.

Here we have the first use of the word to describe Jane’s physical appearance (in Chapter 14, as we have just seen, it is used of her clothes and hairstyle, but not her face). So here, at this moment of emotional distress, she stamps the word on her body: someone who looks like this, she tells herself, is never going to be loved by Mr Rochester. It is a despairing, decisive act of self-definition.

Yet this is not all that is happening. Because of its previous appearances with different meanings, ‘plain’ has become charged with other energies, and their traces are latent here. Plain is not only about how you look: it is also about speaking plainly, about hearing clearly, about maintaining dignity, about seeing things as they are. As she tells the plain truth about her own, plain looks, Jane makes it possible for her readers to understand that there is more to plainness than meets the eye.

Physical plainness is not only an addition to the other kinds: it also helps them to come into being. Jane’s unremarkable physical appearance makes it easier for her to see and say things as they are. Beautiful, rich creatures like Blanche are caught up in a world that is in many ways not ‘real’: privileged, idealised, puffed with compliments and romantic possibilities. Condemned to — or blessed with — plainness, Jane must stand outside those gossamer realms, and therefore can see through them, as when, later in the novel, she understands that Mr Rochester does not really love Blanche, however much he might be acting as though he does.

In the animation and array, you will see that only one of the translations — Božena Legiša-Velikonja’s Slovenian version of 1970 — uses the same term for these two instances of ‘plain’. Some of the other translations connect the first instance to ‘the plain truth’ in chapter 12: Marie von Borch (Ge1888), Elvi Kippasto (E1959), and Ugo Dèttore (It1974) all use words approximating to ‘simple’ in both cases. The two Italian translations published in 2014 perform a switcharound: Monica Pareschi chooses ‘semplice’ (‘simple’) here and ‘nuda e cruda’ (‘nude and raw’) back in chapter 12, while Stella Sacchini does exactly the reverse.

Overall, though, it is again the semantic plurality bursting out in the translations that is most striking. Beyond ‘simple’, the ‘plain’ of ‘plain, unvarnished tale’ is rendered by words approximating to ‘sobriety’, ‘unadorned’, ‘as they really stood’, ‘without spices’, and more; while the ‘plain’ of ‘poor, and plain’ morphs into words that roughly correspond to ‘ugly’, ‘simple’, ‘dull’, ‘insignificant’, ‘ordinary’ and ‘unimpressive’. One especially surprising and suggestive shift is created by Irinarkh Vvedenskii’s Russian translation of 1849. It renders the second ‘plain’ as безпріютной, ‘shelterless’, thereby bringing in the sense of ‘plain’ when used as a noun: a flat expanse of landscape. It is as though Jane is anticipating her later wanderings on the moors around Whitcross: disconnected, poor, an outcast on the plain.6

Animation 10: plain, unvarnished … poor, and plain

https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12434/7fac4507

D2016 usmykket [unadorned] … uanselig [unimpressive]

D2015 ligefrem [straightforward] … grim [ugly]

It2014 una storia semplice e senza fronzoli [a simple tale without frills] … povera, scialba e sola al mondo [poor, dull and alone in the world]

R1999 просто, не приукрашая и не преувеличивая [simply, without embellishing or exaggerating] … безродной, бедной, некрасивой [ancestryless, poor, ugly]

It1974 una semplice e disadorna storia [a simple and unadorned tale] … un po’ sciocca, povera e semplice [a bit foolish, poor and simple]

E1959 talle omase lihtsa ning ilustamata seletuse [a simple, unvarnished tale] … Üksiku, vaese ja inetu [lonely, poor and ugly]

It1951 le cose così come realmente stavano [things as they really stood] … brutta, povera, e senza parentela [ugly, poor, and without kin]

It1925 un semplicissimo racconto [a very simple tale] … povera, brutta e senza famiglia [poor, ugly, and without family]

Ge1888 eine einfache, ungeschmückte Erzählung [a simple, unadorned tale] … armen, alleinstehenden, hässlichen [poor, single, ugly]

a plain, unvarnished tale … disconnected, poor and plain

Ru1849 и выслушавъ рядъ взведенныхъ обвиненій [having heard a series of accusations brought (against me)] … безродной, бѣдной, безпріютной [ancestryless, poor, shelterless]

It1904 le cose così com’erano [things as they were] … brutta, povera e senza attinenze di famiglia [ugly, poor, and without family connections]

R1950 со свойственной ему трезвостью [with his characteristic sobriety] … одинокой, неимущей дурнушки [solitary, poor, unattractive]

Sl1955 jasno [clearly] … preproste [plain]

Sl1970 preprosto [plainly] … preproste [plain]

Ge1979 bewies in ihrer ruhigen ungeschminkten Art [showed in her quiet, unadorned way] … armen, mißgestalteten und unansehnlichen [poor, deformed and unattractive]

Hi2002 मिर्च-मसाले से रहित कहानी [{mirc-masāle se rahit kahānī} a story without spices] … साधारण [{sādhāraṇ} general]

It2014S una storia, nuda e cruda [a nude, raw tale] … senza famiglia, povera e insignificante [without family, poor and insignificant]

Ge2015 einen unverblümten, ungeschminkten Bericht [a blunt, unadorned report] … ohne Verbindungen, arm und gewöhnlich [without ties, poor and ordinary]

Plain, and Little

We are in Chapter 23 and a lot has happened since our last point of focus. There has been the house party at Thornfield, during which Mr Rochester seemed to woo Blanche Ingram; there has been his appearance in disguise as a gypsy fortune teller; there has been the arrival and mysterious wounding of Mr Mason, from Jamaica; and then Jane has gone away for a month to attend the death-bed of Aunt Reed at Gateshead Hall. Since her return to Thornfield there has been ‘a fortnight of dubious calm’.

Now, Jane has encountered Mr Rochester in the garden, and he — with what must seem extraordinary cruelty — has been goading her with the news that he will soon marry Miss Ingram, and she will have to go away. In response, her love for what she would have to leave behind bursts out of her:

‘I love Thornfield … I have talked, face to face, with what I reverence; with what I delight in, — with an original, a vigorous, an expanded mind. I have known you, Mr. Rochester; and it strikes me with terror and anguish to feel I absolutely must be torn from you forever.’

Startlingly, he then changes tack and tells her that she won’t have to leave after all. Distraught, she reacts again:

‘Do you think I can stay to become nothing to you? Do you think I am an automaton? … Do you think, because I am poor, obscure, plain, and little, I am soulless and heartless? — You think wrong! — I have as much soul as you, — and full as much heart! … I am not talking to you now through the medium of custom, conventionalities, nor even of mortal flesh: — it is my spirit that addresses your spirit; just as if both had passed through the grave, and we stood at God’s feet, equal, — as we are!’

The word ‘plain’ appears here with the same pained meaning of physical unattractiveness that we saw in Chapter 16. Yet Jane’s utterance also embodies the other, more positive senses of ‘plain’: seeing things clearly, and speaking out in defiance of convention.

Her speech strikes home. Rochester declares that he loves Jane, not Blanche Ingram. He proposes in words that echo hers:

‘You — you strange — you almost unearthly thing! — I love as my own flesh. You — poor and obscure, and small and plain as you are — I entreat to accept me as a husband.’

In the animation and array, you will see the prismatic diffractions of the first appearance of ‘plain’ in this chapter: ‘I am poor, obscure, plain, and little’. One thing to bear in mind is that the translators are — as always — faced, not with the word by itself, but as part of a phrase or sentence. In this case, the sequence ‘poor, obscure, plain, and little’ has a marked, emotive rhythm: ‘tum, ti tum, tum, ti tum ti’. When Juan G. de Luaces leaves out ‘plain, and little’ from his Spanish translation in 1943 it is probably not because he dislikes those words, and not from carelessness, but because he wants to keep a strong rhythm pulsing through the sentence that he writes, helped by a pattern of alliteration (‘P—p—p—sc—c—c’): ‘¿Piensa que porque soy pobre y oscura carezco de alma y de corazón?’ (‘Do you think that because I am poor and obscure I am lacking in soul and heart’). For Lesbazeilles-Souvestre in 1854, on the other hand, the closeness of French to English enabled her to match word with word while keeping almost the same rhythm: ‘je suis pauvre, obscure, laide et petite’.

‘Laide’ is an obvious term for a French translator to adopt: it means roughly the same as ‘plain’ in this context, is a monosyllable, and even has three letters in common with the English word. Yet Lesbazeilles-Souvestre’s choice makes a decisive change in the novel’s web of words, for ‘laide’, or ‘laid’ in the masculine, is also used to translate ‘ugly’.

This shift will be explored more fully in the next section. Here, in our prismatic expansion of ‘I am poor, obscure, plain and little’, we can see a similar choice being made by translators who opt for ‘hässlich’ in German, ‘brutta’ in Italian or ‘grim’ in Danish. Others take a different path, avoiding the conflation of ‘plain’ with ‘ugly’, and further opening up its semantic complexity as they do so.

Animation 11: plain, and little7

https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12434/cb0d066a

D2015 grim [ugly]

It 2014S sono povera, sconosciuta, insignificante e piccola [I am poor, unknown, insignificant and small]

Sp2009 soy pobre, silenciosa, discreta y menuda [I am poor, silent, modest and small]

Hi2002 निर्धन, परिवारविहीन, सामान्य शक्ल-सूरत की और छोटी हूँ [{nirdhan parivārvihīn, sāmānya śakla-sūrat kī aur choṭī hūṁ} poor, without family, ordinary looking, and small]

Ge1979 ich arm, unbedeutend, häßlich und klein bin [I am poor, insignificant, ugly and small]

F1966 je suis pauvre, insignifiante, laide et menue [I am poor, insignificant, ugly and slight]

E1959 ma olen vaene ja tähtsusetu, ilutu ja väike [poor and unimportant, unlovely and little]

Sl1955, 1970 preprosta [plain]

R1950 если я небогата и незнатна, если я мала ростом и некрасива [if I am not rich and not noble, if I am of small stature and plain]

Sp1943 soy pobre y oscura [I am poor and obscure]

It1904 son povera, oscura, brutta, piccina [I am poor, obscure, ugly, little]

F1854 je suis pauvre, obscure, laide et petite [I am poor, obscure, ugly and little]

I am poor, obscure, plain, and little

R1849 я бѣдна и не принадлежу къ вашему блистательному кругу [I am poor and do not belong to your brilliant circle]

Ge1888 weil ich arm und klein und hässlich und einsam bin [I am poor and small and ugly and alone]

It1925 son povera, umile, piccola e senza bellezza [I am poor, humble, small and without beauty]

Sp1947 soy pobre, insignificante y vulgar [I am poor, insignificant and vulgar]

It1951 sono povera, oscura, brutta e piccola [I am poor, obscure, ugly and small]

D1957 ubetydelig [insignificant]

F1964 je suis pauvre, humble, sans agrément, petite [I am poor, humble, without pleasant features, little]

It1974 sono povera, oscura, semplice e piccola [I am poor, obscure, simple and small]

R1999 я бедна, безродна, некрасива и мала ростом [I am poor, ancestry-less, plain and of small stature]

F2008 je suis pauvre, obscure, quelconque et menue [I am poor, obscure, ordinary and slight]

It2014 sono povera, oscura, brutta e piccola [I am poor, obscure, ugly and small]

Ge2015 ich arm bin, unbedeutend, unansehnlich und klein [I am poor, insignificant, unattractive and small]

D2016 uanselig [unimpressive]

Ugly and Laid(e)

As we saw in the last section, Noémi Lesbazeilles-Souvestre’s French version of 1854 translates ‘plain’ in Chapter 23, with a word, ‘laid(e)’, which she also uses to translate ‘ugly’. This matters because Brontë maintains a firm distinction between those two terms. ‘Plain’ is associated with Jane and has the range of meanings that we have been exploring. ‘Ugly’ is associated with Mr Rochester: it is used mainly of his physical appearance, but it can also apply to his behaviour (‘bigamy is an ugly word!’ — as he exclaims in Chapter 26.) A good three-word summary of Jane Eyre in English might be ‘plain meets ugly’, with all that this entails: feminine meets masculine, directness meets deceit, clarity meets obfuscation, poverty meets wealth, innocence meets exploitation. But in the French of Lesbazeilles-Souvestre the verbal dynamic is altered. The differences between Jane and Rochester are reduced and the likeness is made more visible. In her translation, ‘laide’ meets ‘laid’.

This shift is in tune with the idiom of French nineteenth-century fiction. Women characters in novels by Balzac, Sand, Hugo, Sue and others frequently declare ‘je suis laide’ (‘I am ugly’), as a search of the ARTFL-FRANTEXT database reveals, whereas the equivalent English database, LION, yields only one instance of a woman saying ‘I am ugly’ in a nineteenth-century novel (Priscilla, in George Eliot’s Silas Marner).8 So, as a translation choice in this instance, ‘laide’ is entirely justifiable. Neverthelesss, as similar decisions are made throughout the novel, and the word ‘laid(e)’ proliferates, a decisive change is effected in the web of words describing people’s looks. In Lesbazeilles-Souvestre’s translation, ‘laid(e)’ (or, in one case, ‘laideurs’) appears in all the following instances, where it is used to translate the English words that I have put in bold in the animation and array.

Animation 12: ugly and laid(e)

https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12434/628b4f4d

Ch. 3 (Mr. Lloyd) he had a hard-featured yet good-natured looking face

Ch. 11 (Grace Poole) a set, square-made figure, red-haired, and with a hard plain face

Ch. 14 (Mr. Rochester) I am sure most people would have thought him an ugly man; yet there was so much unconscious pride in his port; so much ease in his demeanour

Ch. 15 (Mr. Rochester and Céline) He thought himself her idol, ugly as he was

Céline; who even waxed rather brilliant on my personal defects — deformities she termed them

(the possibility that Adèle is his daughter) and perhaps she may be; though I see no proofs of such grim paternity written in her countenance

And was Mr. Rochester now ugly in my eyes?

Ch. 16 (Jane worries Mr. Rochester may have had a liaison with Grace Poole) But, having reached this point of conjecture, Mrs. Poole’s square, flat figure, and uncomely, dry, even coarse face, recurred so distinctly to my mind’s eye, that I thought ‘No; impossible! my supposition cannot be correct.’

‘Portrait of a Governess, disconnected, poor, and plain.’

Ch. 17 (of Mr. Rochester) Most true is it that ‘beauty is in the eye of the gazer.’ [The French back-translates as ‘what some find ugly can seem beautiful to others’)

(Blanche Ingram exclaims) I grant an ugly woman is a blot on the fair face of creation [‘woman’ is italicised in Brontë’s text]

Ch. 18 (the Gypsy — Mr. Rochester in disguise) ‘A shockingly ugly old creature, Miss; almost as black as a crock.’

Ch. 21 (Jane describes Mr Rochester to Bessie, on her visit to Gateshead) I told her he was rather an ugly man, but quite a gentleman

(Georgiana sees Jane’s sketch of Mr. Rochester) but she called that ‘an ugly man.’

Ch. 23 (Jane to Mr. Rochester in the garden — the instance we explored in the last section) ‘because I am poor, obscure, plain and little’

(Mr. Rochester to Jane) ‘You — poor and obscure, and small and plain as you are — I entreat to accept me as a husband.’

Ch. 24 (Jane) I looked at my face in the glass, and felt it was no longer plain

(Jane to Mr. Rochester) ‘I am your plain, Quakerish governess.’

Ch. 35 (Jane to Diana about the idea of marrying St John Rivers) ‘And I am so plain, you see, Die. We should never suit.’ ‘Plain! You?’

Ch. 37 (Mr. Rochester asks) ‘Am I hideous, Jane?’

(And jealously he asks about St John Rivers) ‘Is he a person of low stature, phlegmatic, and plain?’

As you can see, in Brontë’s English these instances are divided between ‘plain’ and ‘ugly’ — and occasionally other terms. In the French of Lesbazeilles-Souvestre they are all brought together into the embrace of a single word.

Ugly and Brutto/a

The anonymous translator of the first Italian Jane Eyre, published in 1904, had Lesbazeilles-Souvestre’s French version open in front of them as they worked, alongside Brontë’s English. And they followed Lesbazeilles-Souvestre in abolishing the English distinction between ‘plain’ and ‘ugly’. Where she wrote ‘laid(e)’, they put the nearest Italian equivalent — ‘brutto’ and its derivatives — in almost every instance. There is just one case where the Italian translator deviates from Lesbazeilles-Souvestre’s example: right at the end of the novel, in Chapter 37, where Rochester asks Jane if he is ‘hideous’, the Italian gives, not ‘brutto’, but ‘orribile’ (horrible).

Yet ‘brutto’ does not have exactly the same range as ‘laid’. It can be used more casually, for instance to talk about bad weather: ‘brutto tempo’. The 1904 Italian translator exploits this flexibility in the word: ‘brutto’ and its derivatives appear 29 times in their translation where ‘laid’ etc had appeared only 22 times in Lesbazeilles-Souvestre — this despite the fact that the 1904 Italian version shrinks the text to about 145,000 words in length, by contrast with Brontë’s c. 189,000 and Lesbazeilles-Souvestre’s c. 193,000. To the list of instances translated by Lesbazeilles-Souvestre with ‘laid’, the 1904 Italian translator adds one ‘ugly’ used of James Reed in Chapter 1 (Lesbazeilles-Souvestre had rendered this with ‘repoussante’, ‘repulsive’):

I knew he would soon strike, and while dreading the blow, I mused on the disgusting and ugly appearance of him who would presently deal it.

Thereafter, ‘brutto’ and its derivatives draw all the following extra moments into their net (again, bold indicates the word(s) translated with ‘brutto’ or a derivative):

Animation 13: ugly and brutto/a

https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12434/f7205298

Ch. 4 ‘Deceit is, indeed, a sad fault in a child,’ said Mr. Brocklehurst

Ch. 5 (at Lowood School) Above twenty of those clad in this costume were full-grown girls; or rather young women: it suited them ill, and gave an air of oddity even to the prettiest

Ch. 9 (the view from Lowood in Spring) How different had this scene looked when I viewed it laid out beneath the iron sky of winter, stiffened in frost, shrouded with snow! When mists as chill as death wandered to the impulse of east winds along those purple peaks, and rolled down ‘ing’ and holm till they blended with the frozen fog of the beck! [all the words in bold are rendered by ‘quella brutta stagione’, ‘that season of bad weather’]

Ch. 11 (the first morning at Thornfield) I looked at some pictures on the walls (one I remember represented a grim man in a cuirass, and one a lady with powdered hair and a pearl necklace)

Ch. 16 (Reason attacks Jane’s dream of closeness to Rochester) ‘is it likely he would waste a serious thought on this indigent and insignificant plebeian?’

Ch. 29 (Jane gets up for the first time at Marsh-End / Moor-House) My clothes hung loose on me; for I was much wasted: but I covered deficiencies with a shawl

These additional instances soften the linguistic focus of the text. They help us to see, by contrast, how it matters that Brontë’s English gave particular attention to ‘plain’, together with its relation to ‘ugly’; and indeed how it matters — in a different way — that the French of Lesbazeilles-Souvestre merged the two terms of that articulation, so as to give distinctive prominence to the ‘laid(e)’.

Works Cited

For the translations of Jane Eyre referred to, please see the List of Translations at the end of this book.

Artfl-Frantext, https://artfl-project.uchicago.edu/content/artfl-frantext

1 Proquest Literature Online, https://www.proquest.com/lion

2 See Essay 9 above, by Ana Teresa Marques dos Santos and Cláudia Pazos-Alonso.

3 This animation and array incorporate research by Caterina Cappelli, Andrés Claro, Mary Frank, Jernej Habjan, Abhishek Jain, Eugenia Kelbert, Madli Kütt, and Céline Sabiron.

4 This animation and array incorporate research by Caterina Cappelli, Mary Frank, Jernej Habjan, Abhishek Jain, Eugenia Kelbert, Ida Klitgård, Madli Kütt, and Céline Sabiron.

5 This animation and array incorporate research by Caterina Cappelli, Mary Frank, Jernej Habjan, Abhishek Jain, Eugenia Kelbert, Ida Klitgård, and Madli Kütt.

6 This animation and array incorporate research by Caterina Cappelli, Mary Frank, Jernej Habjan, Abhishek Jain, Eugenia Kelbert, Ida Klitgård, and Madli Kütt.

7 This animation and array incorporate research by Caterina Cappelli, Andrés Claro, Mary Frank, Abhishek Jain, Eugenia Kelbert, Ida Klitgård, Madli Kütt, and Céline Sabiron.

8 Artfl-Frantext, https://artfl-project.uchicago.edu/content/artfl-frantext.