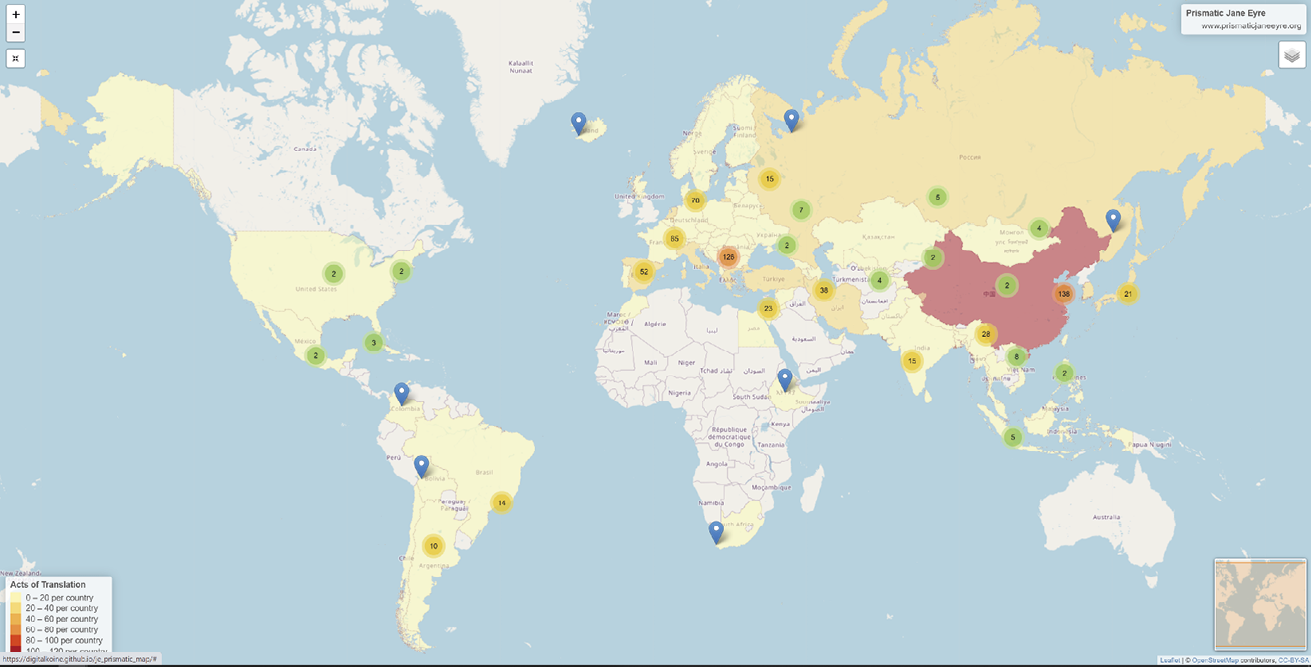

The World Map https://digitalkoine.github.io/je_prismatic_map Created by Giovanni Pietro Vitali; maps © Thunderforest, data © OpenStreetMap contributors

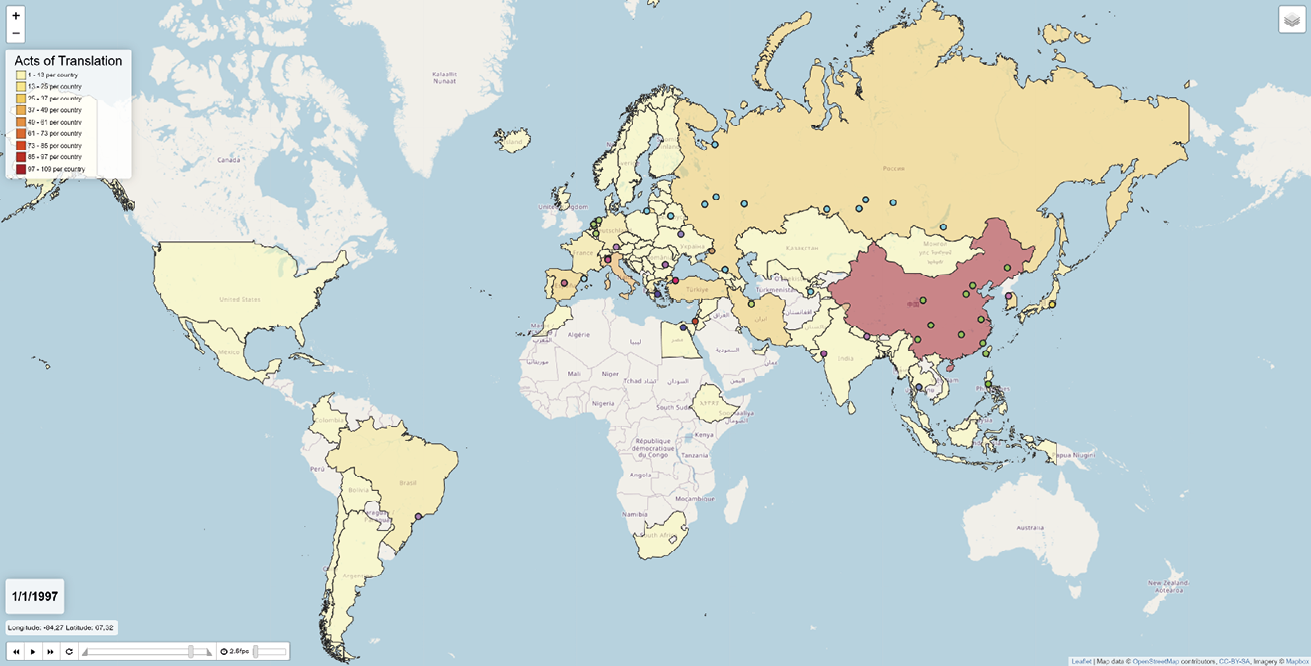

The Time Map https://digitalkoine.github.io/translations_timemap Created by Giovanni Pietro Vitali and Simone Landucci;© OpenStreetMap contributors, © Mapbox

VII. ‘Walk’ and ‘Wander’ through Language(s); Prismatic Scenes; and Littoral Reading

© 2023 Matthew Reynolds, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0319.22

Like ‘plain’ and ‘ugly’ (discussed in Chapter V), ‘walk’ and ‘wander’ form a significant contrast, one that is threaded throughout the text. A walk appears in the novel’s very first sentence, and wandering appears in its second:

There was no possibility of taking a walk that day. We had been wandering, indeed, in the leafless shrubbery an hour in the morning …

Headlined in this way, the words gesture towards a long history of literary works made from walks and wanderings. John Bunyan’s The Pilgrim’s Progress — a strong influence on Jane Eyre — begins:

As I walk’d through the wilderness of this world1

Dante’s Commedia starts, not only in medias res (as Horace recommended epics should), but also in the middle of a walk:

Nel mezzo del cammin di nostra vita

(In the middle of the walk of our life)2

There is a Christian tonality to these echoes which is in tune with the Biblical references discussed by Léa Rychen in Essay 14; but the roots of wandering and walking also spread wider. Homer’s Odyssey, in its opening lines, describes Odysseus as a man ‘wandering from clime to clime’3 — at least, that is Alexander Pope’s translation, the one the Brontës were most likely to have known. Nearer to Charlotte Brontë’s own time, Wordsworth had made much poetry from country walks, and Book 1 of his 1814 volume The Excursion was called ‘The Wanderer’. Dickens’s Oliver Twist, or the Parish Boy’s Progress (1838) was a bestseller in the years of Jane Eyre’s gestation, and a decisive early turn in the plot happens when, as the title of Chapter 8 announces, ‘Oliver Walks to London’.

So with its opening sentence, ‘There was no possibility of taking a walk that day’, Jane Eyre both marks its difference from these precedents and taps their energy to create a potential: when will the walk be possible? It signals the likelihood that the obstruction or achievement of journeys may play a substantial part in the novel; and so it turns out to be, with Jane’s variously troubled displacements from one defining location to another: Gateshead to Lowood; Lowood to Thornfield; Thornfield to Whitcross, Marsh End and Morton; back to Thornfield, and finally on to Ferndean. None of these journeys is merely physical; each represents some kind of step, whether happy or not, in the personal development that the Bildungsroman genre (to which Jane Eyre is affiliated) encourages readers to expect.

The distinction between ‘walk’ and the alternative provided by the second sentence, ‘wandering’, gives readers a miniature, two-word thesaurus with which to begin to make sense of the novel’s physical and mental journeys. ‘Walk’ is more decisive, and implies a direction. Charlotte Brontë herself relished a long, brisk walk: though walking was her everyday mode of transport — to church, shops, friends — her letters are still full of the enjoyment of striding across the moors. Jane, however, announces her opposite view in the second paragraph of the book, and she uses the inaugural appearance of her assertive first-person pronoun to do so: ‘I was glad of it; I never liked long walks’. At that moment, we can sense the young character being separated from her heartier adult author; but as Jane grows up, she too comes to like the independence of walking alone, as when, on her return from Mrs Reed’s deathbed in Chapter 22, she chooses to walk from Millcote to Thornfield, a distance that (as we know from Chapter 11) is ‘a matter of six miles’. Walking is not always done so vigorously, yet even when there is no physical destination, there is always an emotional purpose. This is especially so in the charged moments when a man is walking with a woman. When Rochester walks with Jane in Chapter 15 he tells her of his past with Céline Varens; and when they walk together in Chapter 23 he proposes marriage, as St John Rivers in his turn will do during a walk in Chapter 34.

‘Wandering’, on the other hand, has no evident physical or emotional direction. It can be carefree, as when the young Jane ‘wandered far’ with Mary Ann at Lowood, or desperate, as when the older Jane, having fled from Thornfield to Whitcross, ‘wandered about like a lost and starving dog’.4 Wandering also lends itself — much more than ‘walk’ — to metaphor: there can be wandering from the straight and narrow, as with Rochester’s past life in Chapter 20; and thoughts and words can wander in the mind, whether in a daydream during dull lessons at Lowood school (Chapter 6) or in the agony of Jane’s despair after the failed wedding (Chapter 26).

‘Wander’ in Hebrew and Estonian

If you trace recurrences of ‘walk’ and ‘wander’ through the novel, you see the words gathering significance; and all the more so if you have the never-exactly-parallel texts of some translations alongside. In Hebrew, as Adriana X. Jacobs notes, there are many overlapping terms for ‘wander’ and, since wandering features crucially in the Hebrew Bible, the choice of words can carry a particular charge. In Chapter 3, after the incident in the red room, Jane seeks consolation in Gulliver’s Travels, a book she usually loves. Only now it has lost its former charm:

… all was eerie and dreary; … Gulliver a most desolate wanderer in most dread and dangerous regions.

Jacobs points out that Sharon Preminger, in 2007, translates ‘wanderer’ as ‘נווד’ [navad], a Modern Hebrew word ‘closely associated with wandering as migration, as exile. In Genesis 4, Cain flees to the city of “Nod”, which is etymologically related to “navad”.’ And the suggestion of exile continues: just a few lines later, when Bessie starts singing a song, ‘in the days when we went gypsying’, Preminger draws on the same verbal field: ‘בימי נדודינו’ ([be-yamei nedudeinu] in the days of our wanderings).5 Six decades earlier, another Hebrew translator, Hana Ben Dov, gave similarly focused imaginative attention to wandering, translating the description of Gulliver as ‘נודד בודד בארץ אויבת’ ([noded boded be-erets oyevet] a solitary wanderer in an enemy land).6 Jacobs comments that the phrase ‘“erets oyevet” is striking, and one wonders whether Ben Dov’s language is shaped by her historical context, namely, the Second World War and the conditions of Jewish life in the final years of the British Mandate’. In these translations, we can see the influence of a Biblical understanding of wandering, which Brontë would have partly shared, passing through the text of Jane Eyre and emerging with distinctive force in new historical moments and imaginative communities.

In Elvi Kippasto’s 1959 Estonian translation, studied by Madli Kütt, we can discover the range of significance that Brontë spans with the word ‘wander’. In this selection of instances, Kippasto reaches for a different Estonian word each time.

Animation 14: ‘wander’ in Estonian

https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12434/06db0996

Ch. 1 We had been wandering, indeed, in the leafless shrubbery uitasime (wandering)

Ch. 3 Gulliver a most desolate wanderer kes eksleb (who is wandering, with a connotation of getting lost)

Ch. 6 your thoughts never seemed to wander püsivad (always stay)

Ch. 9 when mists as chill as death wandered liikusid (were moving)

Ch. 12 a metallic clatter, which effaced the soft wave-wanderings loodusehääled (sounds of nature)

Ch. 17 vague suggestions kept wandering across my brain vilksatas (skimmed)

Ch. 20 Is the wandering and sinful, but now rest-seeking and repentant, man justified ränduril (wanderer)

Ch. 28 I drew near houses; I left them, and came back again, and again I wandered away minna (went)

Ch. 37 I arrested his wandering hand, and prisoned it in both mine.otsiva (searching)

As Kütt points out, more is going on in each of these examples than the isolated choice of a word. The instance from Chapter 9, where the mists simply ‘liikusid’ (‘were moving’) rather than ‘wandered’, is part of a general lightening of the metaphorical weight of that passage: in Kippasto’s Estonian, the mists are also just mists, no longer ‘chill as death’. In Chapter 17, the suggestions that Jane might leave Thornfield seem to be just starting, rather than continuing (‘kept wandering’). In Chapter 6, where Helen’s thoughts never seem to wander, Kippasto keeps the verb for ‘wander’ that she used at the start of the novel, ‘uitama’, for Jane’s own thoughts, which, a bit further on in the English sentence, ‘continually rove away’. So ‘wander’ wanders in this translation: we can observe, not only the variety of meanings that become explicit in Kippasto’s Estonian, but also, by contrast, the insistence with which Brontë re-uses the English word in different, variously literal and metaphorical contexts, charging it with meaning.

‘Parsa’ in Persian

In Hebrew and Estonian we have seen translators opening out the significances of the word ‘wander’ by choosing varied possible equivalences at different moments of the text and under the pressure of distinct historical circumstances. But this splitting and diffraction of meaning is not the only way that translation can go to work upon the verbal material of the source. It can also do the opposite, linking what had been occurrences of different words in the source, and binding them together into new key terms.

Kayvan Tahmasebian has traced this happening in Persian. Two recent translators, Bahrami Horran (1996) and Reza’i (2010), have both translated the novel’s first ‘wander’, ‘we had been wandering, indeed, in the leafless shrubbery’, with ‘پرسه زده بودیم’ {parsa zadan}. Tahmasebian notes that the word ‘parsa’ which is used for “wandering” contains the same connotations of aimlessness as indicated in the context of the original novel. However, etymologically, it is a contracted form of the Persian word ‘pārsa’ which means “to beg” as well as “a beggar”. It originally denotes the movement of beggar, here and there, in order to ask for (porsidan) something. It was part of the customs in some Sufi sects in which a disciple was asked to wander around the town, like a beggar, and recite poems, in order to suppress pride and vanity in him (Dehkhoda Dictionary).

Tahmasebian has traced the word ‘parsa’ throughout Reza’i’s translation, and has found that it renders a variety of English words, establishing a new network of association between the moments when they appear. The words are ‘walk’, ‘stroll’, ‘fly’, ‘stray’, ramble’ and — interestingly — ‘haunt’. Here are their occurrences (every word in bold is translated using ‘parsa’).

Animation 15: ‘parsa’

https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12434/3121b8ca

Ch. 4 (Jane alone in the nursery) I then sat with my doll on my knee till the fire got low, glancing round occasionally to make sure that nothing worse than myself haunted the shadowy room

Ch. 5 (Jane waits in an inn on her way to Lowood school) Here I walked about for a long time, feeling very strange, and mortally apprehensive of someone coming in and kidnapping me

Ch. 12 (Jane awaits the appearance of the figure who turns out to be Mr. Rochester) As this horse approached, and as I watched for it to appear through the dusk, I remembered certain of Bessie’s tales, wherein figured a North-of-England spirit called a ‘Gytrash’, which, in the form of horse, mule, or large dog, haunted solitary ways

Ch. 15 (Mr. Rochester, before he sees Céline with the vicomte)and I was tired with strolling through Paris

Ch. 23 (Jane in the orchard, before Mr. Rochester proposes)Here one could wander unseen. While such honey-dew fell, such silence reigned, such gloaming gathered, I felt as if I could haunt such shade forever

Ch. 24 (Mr. Rochester) Ten years since, I flew through Europe half mad

Ch. 25 (Jane waits for Mr. Rochester to return on the evening before their planned wedding) Here and there I strayed through the orchard

Ch. 25 (Jane narrates one of her dreams from the night before)I wandered, on a moonlight night, through the grass-grown enclosure within

Ch. 26 (on the way to the church to be wed)and I have not forgotten, either, two figures of strangers straying amongst the low hillocks and reading the mementoes graven on the few mossy head-stones

Ch. 28 (Jane penniless near Whitcross) I rambled round the hamlet, going sometimes to a little distance and returning again, for an hour or more

Ch. 28 (Jane reluctant to approach houses, again near Whitcross)I left them, and came back again, and again I wandered away

Ch 36 (The innkeeper describes Mr. Rochester’s behaviour after Jane’s departure)He would not cross the door-stones of the house, except at night, when he walked just like a ghost about the grounds and in the orchard as if he had lost his senses

Tahmasebian comments:

the network thus established between English words (mediated by the Persian word “parsa”) has expected and unexpected knots. While the word “wander” can be easily associated with “walk”, “stroll”, “stray” and “ramble”, the association with “haunt” seems a bit far-fetched. In Persian, this association is made possible through the collocation “ruh-e sargardān” which means “wandering spirit” or “wandering ghost”. These words have been used in the context of popular horror stories that depict ghosts wandering at night. The stories are not rooted in Iranian folk tales but have been imported into modern Iranian culture from European origins. Thus, they have an “originally” translational existence within Iranian culture.

So this new conjunction of moments of ‘parsa’ in the Iranian Jane Eyre opens a new web of associations, centred in Jane’s beggarly wandering around Whitcross, and spreading connotations of dislocation, dispossession and ghostliness into other moments of the novel.

‘Walk’ in Greek

As we have seen, the word ‘walk’ does not have such a wide range of meanings as ‘wander’; but Brontë still recurs to the word insistently. One striking example is in Chapter 27 when, in the wake of the failed wedding, Jane insists that she and Rochester must part:

He turned away; he threw himself on his face on the sofa. ‘Oh, Jane! my hope — my love — my life!’ broke in anguish from his lips. Then came a deep, strong sob.

I had already gained the door: but, reader, I walked back — walked back as determinedly as I had retreated. I knelt down by him; I turned his face from the cushion to me; I kissed his cheek; I smoothed his hair with my hand.

In Greek, the usual word for walk (περπατάω) would sound odd in this context; so the three Greek translations studied by Eleni Philippou have each found different ways of phrasing ‘I walked back — walked back’:

Όμως γυρνούσα πίσω, αναγνώστη, γυρνούσα πίσω (But I was coming back, reader, I was coming back) tr. Ninila Papagiannē, 1949.

Αλλά ξαναγύρισα, ξαναγύρισα (But I returned again, I returned again) tr. Dimitris Kikizas, 1997.

Όμως, καλέ μου αναγνώστη, γύρισα πίσω — γύρισα πίσω (But, my good reader, I turned back — I turned back) tr. Maria Exarchou, 2011.

These alternatives show us something about the Greek language and the choices of the three translators; but they also alert us to similar English alternatives — shadow texts — which Brontë did not use. Not ‘I turned back’; not ‘I returned’; but ‘I walked back’, a choice of words that connects this action, this merely momentary change of direction, to the other decisive walks throughout the novel.

‘Walk’ and ‘Wander’ in Italian and Chinese

Now let us observe a selection of walks, then a selection of wanderings, and finally the two sequences braided together, all given in English, in the recent Chinese translation by Song Zhaolin (Beijing, 2002), and in the anonymous first Italian translation (Milan, 1904). These are obviously very different languages and contexts, yet we can discern similar dynamics at work in both translations as, on the one hand, new connotations and connections appear while, on the other, key contours in Brontë’s handling of both words are followed, and indeed thrown into relief.

The Chinese text, studied by Yunte Huang, translates the opening contrast between ‘walk’ and ‘wandering’ with 散步 ({sanbu} random or scattered footsteps) and 漫步 ({manbu}, wandering footsteps). Both expressions, Huang explains, contain the character 步, which ‘is an ideograph of two feet: the upper half 止 is an image of a foot with toes sticking out, and the lower half is the reverse image.’ As you look down the columns of ‘walk’ and ‘wander’ you can watch this character recurring. As with the instances we have explored above, Song finds varied ways of translating Brontë’s repeated words; but he also establishes patterns of reiteration — most notably when the ‘walk’ 散步 (sanbu) that could not be taken at the novel’s beginning makes a marked reappearance as the ‘walk’ 散步 (sanbu) that Jane and Rochester will for evermore be able to take together after they are reunited at its end.

In Italian, there is a similar mixture of prismatic diffraction of Brontë’s words, and partially matching repetition. Italian has two obvious verbs for walk: ‘passeggiare’, which is more in the sense of going for a walk or stroll, and ‘camminare’, which is more in the sense of being able to walk, or just walking. The anonymous translator makes her or his own patterns with these words. You will see in the animation and array that ‘camminare’ figures on one occasion in the ‘wander’ column (Ch. 23), and it can also appear elsewhere in the novel where Brontë does not write of either walking or wandering. There are likewise two obvious Italian words for ‘wander’: ‘errare’, which includes the sense of error, and ‘vagare’ which is more carefree, a bit like the English ‘drift’. In the animations and array below, you can trace the recurrences of ‘passeggiare’ (including ‘passeggerò’) and ‘errare’ (including ‘errato’, ‘errante’ and ‘erravo’). Just like Song Zhaolin a century later, the anonymous Italian translator reaches for the same verb, ‘passeggiare’, for both the first ‘walk’, which cannot be taken, and the last, which Jane and Mr Rochester will take together. It makes another, similar arc with the verb ‘errare’ which appears both at the novel’s beginning and (used of Rochester’s hand) near its end.

https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12434/d9f915c9

https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12434/4c9ac8ca

Prismatic Scenes (i): The ‘Red-Room’

A step on from the multilingual readings of words that I have offered so far is to attempt something like them for whole episodes of the novel. We have done this for two prismatic scenes: the ‘red-room’, from Chapter 2, and the ‘shape’ in Jane’s bedroom, from Chapter 25. We present the material in the form of animations, created in JavaScript by Paola Gaudio: they ask for your participation as follows. The English text appears in blocks, so you have time to read it. Click on the revolving globe in the bottom right-hand corner to start the translations appearing. You will see that colour is used in two ways: the colour of the text is keyed to the language of the translation, while the colour of the frame around each translation shows you which English words it corresponds to. When all the translations have appeared around a given block of text, click on the revolving globe again to move forward, and click once more to launch the next set of translations. You can also navigate using the numbers in the left-hand margin or the triangles in the bottom left-hand corner. The background is dark so that the colours show up effectively: you may find you want to zoom in on your browser to make the text more legible.

First, the ‘red-room’ — the iconic episode in Chapter 2, where the young Jane, having stood up to John Reed’s bullying, is confined as a punishment. We pick up the scene after the look of the room has been sketched in: the bed with its massive pillars and red damask curtains, the red carpet, the chairs, the glaring white piled-up pillows and mattresses, the windows and the ‘visionary hollow’ of the mirror; after we have learned that Jane’s kind uncle Mr Reed had died there; and after Jane has lamented the injustice of her situation.7

The ‘Red-Room’: JavaScript animation by Paola Gaudio

https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12434/b84f8bc9

The scene in the ‘red-room’ is generative: elements of it recur throughout the novel, from the red and white colour scheme of the drawing room at Thornfield Hall to Jane’s repeated fretting at her life’s restrictions; from the confinement imposed on Bertha Rochester to the possibility of supernatural intervention which, so feared in the red-room itself, is so welcomed near the end of the novel, when it takes the form of Rochester’s voice echoing magically across the moors (Jane’s heart beats ‘thick’ on both occasions).8

In the many plays, films and free re-writings that Jane Eyre has prompted, the scene has continued its recurrent metamorphoses. In Charlotte Birch-Pfeiffer’s stage version (1853) it shrinks to an encounter with a portrait of Mr Reed; in Robert Stevenson’s film of 1943 it morphs into a cluttered cupboard; while in Daphne du Maurier’s Rebecca (1938) it blends with the windowless room occupied by Bertha Rochester and expands into the eerie west wing of Manderley, the domain of the dead first Mrs de Winter.9

In the translations shown in the animation there are, of course, no such free re-makings. Instead, we can watch the translators responding to the challenges of Brontë’s language. The first of these is a particular vocabulary of mental struggle which has its roots in nonconformist writers of Christian spirituality such as John Bunyan and William Blake, but which Brontë moulds to her own emotional purpose in phrases like ‘consternation of soul’, ‘heart in insurrection’, ‘mental battle’. In the animation, you can see some translators matching that phraseology while others reach for alternative terms. Further on, the renderings of words like ‘vassalage’ and ‘heterogeneous’ show translators responding in different ways to the markedly elaborate, adult vocabulary with which Jane, as narrator, recounts the trauma suffered by her younger self. A few changes here and there — like the introduction of a chiming clock, or the upgrading of the hall to a castle — add touches that register and perhaps amplify the gothic tension. And at moments of inward feeling or imagination (‘I was a discord’, ‘a haloed face’) translators find their own ways of expressing Jane’s pain, and her hope which then fades and darkens into terror.

Some of these changes derive from the translators’ individual styles: Eugenia Kelbert points out that the anonymous 1901 Russian translator has a general ‘tendency to translate one word by two close synonyms’. Other choices bear the imprint of their historical and cultural moment — for instance Vera Stanevich’s phrase ‘phosphoric (‘фосфорическим’) brilliance’ in her translation from 1950, and her substitution of ‘mother (‘матерью’) for ‘parent’. In our second prismatic scene we will see such circumstances exerting a more transformative pressure.

Prismatic Scenes (ii): The ‘Shape’ in Jane’s Bedroom

Our second prismatic scene is from near the end of Chapter 25: Jane’s narration to Mr Rochester, on the eve of their planned wedding, of a strange and threatening incursion into her bedroom the night before, by a figure whom she does not yet know to be his current wife, Bertha.

The passage has always been one of the most provocative in the book. It was omitted from the 1849 French version by ‘Old Nick’ (Paul Émile Daurand Forgues), which — as we saw in Chapter I — served as the basis for several later translations into Spanish, German, Swedish and Russian. It nourished some of the novel’s most influential interpretations: Sandra Gilbert and Susan Gubar’s, which reads Bertha as Jane’s double, and Gayatri Chakravorti Spivak’s, which critiques the racism by which her portrayal is afflicted.10

And, as we will see, translators — those who have not gone so far as to cut the passage — have tended to veil it in various ways, perhaps not wanting (or not managing) to match the breathless vividness of Brontë’s style here, while also demurring at the means by which Bertha is dehumanized. When we look at these translations closely, we get a detailed, fresh impression, both of the challenge of this passage, and of how it has been received by readers in different places, languages and times.11

The ‘Shape’ in Jane’s Bedroom: JavaScript animation by Paola Gaudio

https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12434/f6c70608

‘The second time in my life’ — in the last sentence of this passage — points to the first time Jane had lost consciousness from terror: almost a decade, and twenty-three chapters, earlier, in the ‘red-room’. There are some similarities between the scenes: enclosure in a bedroom, and a vividly imagined threat. But the style of the two passages is quite different. In the first, the mature Jane employs all the sophisticated resources of her written language to render the impressions of the child, with complex sentences and (as we have seen) words like ‘consternation’, ‘vassalage’ and ‘cordiality’, which few ten-year-olds would know. In the second, Jane as a young woman is shown speaking in her own urgent, colloquial tongue, with short, simple sentences and everyday words: ‘I thought — oh, it is daylight!’ One way in which translators tame her energy here is by constructing the syntax in more formal ways — as Madli Kütt has remarked of the Estonian translation of this phrase by Kippasto (1959), which can be back-translated, not as ‘I thought — oh’, but ‘I thought that…’ (similar things happen in this and other translations throughout the passage).

Jane has been very frightened, and she reaches for varied means to express her terror. One is the language of racial othering: the ‘savage face’, the ‘red eyes’, the ‘blackened inflation of the lineaments’. Another is the imaginary figure of ‘the Vampyre’. In the prismatic animation we can see translators emphasising this second aspect of the description (al-Baʿalbakī, for instance, adds explanatory words that can be back-translated as ‘the sucker of people’s blood’), while downplaying the first. Andrés Claro points out that both the 1940s Spanish translators, Luaces and Pereda, avoid the word ‘savage’ — and in Essay 5, above, he traces the reasons in their historical moments and political commitments. In such cases, the translators’ muzzling of an aspect of their source can become a form of ethical critique.

Another feature of the text that Brontë wrote to represent Jane’s speech is its wavering as to whether what Jane has encountered is human, or not; a ‘she’ or an ‘it’. What first emerges from the closet was not a person but ‘a form … it was not Leah, it was not Mrs Fairfax’; then ‘it seemed … a woman’ and becomes a ‘she’; but then again, via the description of the face (‘it was a discoloured face’), the figure becomes an ‘it’ again: ‘it removed my veil’; only finally to veer back into humanity and gender: ‘her lurid visage flamed over mine’. Translators vary in their handling of this variation, depending on their choices and also on how pronouns work in the languages they are using: Yunte Huang, in Essay 12, above, has explored several Chinese translations in this regard, while Madli Kütt, in Essay 16, below, provides a detailed discussion of the differently distinctive affordances of Estonian. Reading the translations together, we find a vivid record of the haunting, goading quality of this scene.

It already has that quality in the novel Brontë wrote. Right at the start of Chapter 25, Jane tells us that something strange has happened, and also that she will not explain what it was until later. We are also given an oddly charged description of the ‘closet’ in her bedroom, and the ‘wraith-like apparel’ it contains (i.e., the wedding dress), together with the weighted comment that Mrs Rochester is ‘not I … but a person whom as yet I know not’. None of this makes full sense until the scene of the invasion of the bedroom has been narrated several pages later; and yet, by the time that narration happens, these puzzling details may well have been forgotten — and indeed the scene itself is not fully explained until later again. Where then does this scene belong? In Brontë’s text it floats, eery and ungraspable; and it continues to haunt the translations that encounter it.

Littoral Reading

The prismatic words and scenes that we have explored, throughout Chapters IV, V, VI and VII, have given us a way into the heterolingual complexity of the world Jane Eyre. Reading them, we can see how verbal patterns shape the signifying material of the text that Brontë wrote, and how those shapes morph in translation. To a large extent, the transformations are compelled by the medium the translator is working with and in: their language, repertoire, publishing context and cultural moment; but they are also motivated by individual taste and choice. Studying these never-quite-parallel texts together, we discover the creativity of linguistic, cultural and historical difference, as well as of individual translational imaginations. We also gain a better sense of what was there to be transformed — of the potential that is revealed in the source text through its being translated.

Not all words and scenes yielded the rich variety of those to which I have given full treatment here. Of the words that we researched, some, like ‘mind’, ‘glad’, ‘conscience’, ‘master’ produced a narrower range of interest, as we have seen. Others, like ‘duty’, ‘elf’ or ‘strange’ did not — so far as the research group could ascertain — reveal more than fleeting energies in the translations. This must show us something about the variable imaginative charge that words and their shadows carry, not only within what is defined as being ‘their language’ but across broader landscapes of language variety. But it may also be a sign of our comparatively restricted sample from the vast and variegated word hoard that is the world Jane Eyre. Perhaps, in other translations, and other languages and moments, those other words and their shadows turn out to be deeply interesting.

The approach described in these chapters does not exhaust itself in the discoveries that we have made about the particular words and scenes that we have studied. It also offers itself as a mode of reading suited to world works — that is to say, works that it is impossible to read in all their plural, multilingual vastness. If you can, sample a work in more than one language version. If you cannot do that, you can still read with an awareness that the words and scenes in front of you are translational: they have a disposition to be re-made differently, because they are haunted by shadow texts that can become actual in other repertoires, times and places. This is as true of texts that have not yet been translated as it is of those that are already translations. Read, not literally, but littorally, knowing that the words before you have been cast up onto the white page from the boundlessly transformative seas of language, and will inevitably float off again towards new strands. Reading a world text means being open to the traces of these horizons of meaning, even if the vast majority of them are beyond our ken.

I invite you to keep this wide perspective open, in counterpoint with the tighter focus of the essays that follow, as the volume begins to draw towards its close.

Works Cited

For the translations of Jane Eyre referred to, please see the List of Translations at the end of this book.

Birch-Pfeiffer, Charlotte, ‘Die Waise aus Lowood. Schauspiel in zwei Abtheilungen und vier Acten. Mit freier Benutzung des Romans von Currer Bell’, in Gesammelte dramatische Werke (Leipzig: Reclam, 1876), XIV, pp. 33–147.

Bunyan, John, The Pilgrim’s Progress, ed. W. R. Owens, new edition (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003).

Dante Alighieri, Inferno, ed. Anna Maria Chiavacci Leonardi (Milan: Mondadori, 2016).

du Maurier, Daphne, Rebecca (London: V. Gollancz, 1938).

Pope, Alexander, The Odyssey of Homer: Books I–XII (The Poems of Alexander Pope, vol. 9), ed. Maynard Mack (London: Methuen & Co, and New Haven: Yale University Press, 1967).

1 John Bunyan, The Pilgrim’s Progress, ed. W. R. Owens (OUP, new edn, 2003), p. 10.

2 Dante Alighieri, Inferno, ed. Anna Maria Chiavacci Leonardi (Milan: Mondadori, 2016), p. 57.

3 Alexander Pope, The Odyssey of Homer: Books I–XII (The Poems of Alexander Pope, vol. 9), ed. Maynard Mack (London: Methuen & Co., and New Haven: Yale University Press, 1967), p. 25.

4 JE, Ch. 28.

5 Preminger (2007), p. 29.

6 Ben Dov (1946), p. 18.

7 The animation presents Danish translations by Aslaug Mikkelsen (1957), Christina Rohde (2015) and Luise Hemmer Pihl (2016), selected and back-translated by Ida Klitgård; French translations by Marion Gilbert & Madeleine Duvivier (1919), R. Redon & J. Dulong (1946), Léon Brodovikoff & Claire Robert (1946), Charlotte Maurat (1964), Sylvère Monod (1966) and Dominique Jean (2008), selected and back-translated by Céline Sabiron (with a few additions by Matthew Reynolds); and Russian translations by Irinarkh Vvedenskii (1849), Anon (1849), Anon (1901), Vera Stanevich (1950) and Irina Gurova (1999), selected and back-translated by Eugenia Kelbert. As ever, full publication details are in the List of Translations at the end of this volume.

8 JE, Ch. 35.

9 Charlotte Birch-Pfeiffer, ‘Die Waise aus Lowood. Schauspiel in zwei Abtheilungen und vier Acten. Mit freier Benutzung des Romans von Currer Bell’, in Gesammelte dramatische Werke, vol. 14 (Leipzig: Reclam, 1876), 33–147; Jane Eyre, dir. By Robert Stevenson (20th Century Fox, 1943); Daphne du Maurier, Rebecca (London: V. Gollancz, 1938).

11 The animation presents translations into Spanish, by Juan G. de Luaces (1943), María Fernanda Pereda (1947), Jesús Sánchez Diaz (1974) and Toni Hill (2009), selected and back-translated by Andrés Claro; into Estonian, by Elvi Kippasto (1959), selected and back-translated by Madli Kütt; into Slovenian, by France Borko and Ivan Dolenc (1955) and Božena Legiša-Velikonja (1970), selected and back-translated by Jernej Habjan; into Arabic by Munı̄r’ al-Baʿalbakı̄ (1985), selected and back-translated by Yousif M. Qasmiyeh; into Polish by Emilia Dobrzańska (1880), Teresa Świderska (1930), selected and back-translated by Kasia Szymanska; and into Greek by Polly Moschopoulou (1991) and Maria Exarchou (2011), selected and back-translated by Eleni Philippou. As ever, full publication details are in the List of Translations at the end of this volume.