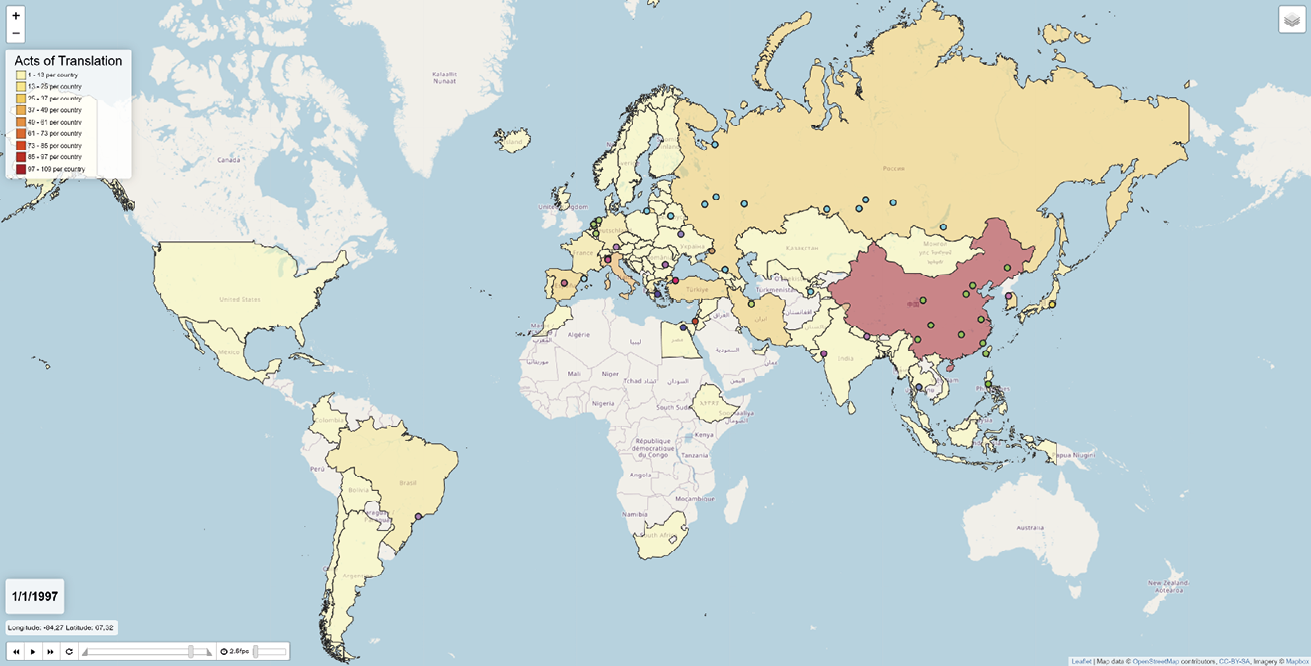

The General Map https://digitalkoine.github.io/je_prismatic_generalmap/ Created by Giovanni Pietro Vitali; © OpenStreetMap contributors

The Time Map https://digitalkoine.github.io/translations_timemap/ Created by Giovanni Pietro Vitali and Simone Landucci;© OpenStreetMap contributors, © Mapbox

Introduction

© 2023 Matthew Reynolds, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0319.01

Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre is not only a novel in English. It is a world work, co-existing in at least 618 translations, by at least as many translators, and spreading over an ever-extending period of years — currently 176 — into at least 68 languages. How can we grasp this vast phenomenon? What questions should we ask of it? With what tactics and tools? What kind of understanding can we hope to achieve? The large and multimodal text that lies before you presents some answers.

In doing so, it aims to contribute to several fields. To world literary studies, by showcasing the complexities inherent in the transnational circulation of a text through language difference, and uncovering the generativity of that process, which involves the imaginative energies of many people, and meshes with their historical moments and political commitments. To English literary studies, by revealing how extremely the reach of a text such as Jane Eyre, and therefore the contexts relevant to its interpretation, exceed the boundaries typically drawn around English literature and the English language: both kinds of ‘English’ are porous, continually tangling and merging with other literature(s) and language(s). To translation studies, by presenting, not only a massively detailed instance, but a corresponding theorisation of translation’s inevitably pluralising force, of its role in co-creating the work that is often thought of as simply ‘being translated’, and of why translation is best seen as happening, not between separate languages, but through a continuum of language difference.

Prismatic Jane Eyre presents some innovations in the methodology of literary history and criticism. It makes use of digital techniques, but braids them into longer-standing practices of literary-critical reading and literary-historical scholarship. Facing the start of this Introduction, you will see links to interactive maps of the kind associated with ‘distant reading’, as pioneered by Franco Moretti;1 and they will recur, in varying configurations, throughout the pages that follow. In the second half of the book, from Chapter IV onwards, you will also find interactive media of an almost opposite character: trans-lingual textual animations inspired by the digital media art of John Cayley.2 These elements both frame and connect the various literary-critical readings, each anchored in a different location, that are presented by the volume’s many co-authors. This intensely co-operative structure is our work’s main methodological step forward. The world is made of language difference, and any consideration of a text in world-literary contexts needs to address this fact. Reading collaboratively is a good way to do it, and we hope that the practice we present in this volume may serve as a model for the collaborative close reading of other texts in the world.

So large and varied a book, with so many co-authors, of course builds on many precedents: they are noted and engaged with throughout the chapters and essays that follow. But let me here, as a first orientation, indicate some of our main points of reference. Our overall approach learns from Édouard Glissant in seeing both literature and scholarship as participating in a ‘poétique de la relation’ [poetics of relatedness]. Our research is therefore not shaped by metaphors of conquest or discovery, but rather by the example of ‘l’errant’ [the wanderer] who ‘cherche à connaître la totalité du monde et sait déjà qu’il ne l’accomplira jamais’ [seeks to understand the totality of the world, all the while knowing that he will never manage it].3 Though we present a large amount of knowledge and discussion of Jane Eyre in world-literary contexts, there is a great deal more material that we have not been able to address, and which indeed could never be grasped in full. Selection is basic to our enterprise, and everything we provide here has a metonymic relationship, and therefore a partial one, to the larger phenomenon that is Jane Eyre as a world work. No doubt the study of any book, in any context, is always in some sense incomplete; but incompleteness is a pervasive and unignorable feature of the study of literature in world contexts.

The arguments of Francis B. Nyamnjoh have helped us to embrace this condition of our research. He notes that, in Africa, ‘popular ideas of what constitutes reality … are rich with ontologies of incompleteness’, and proposes that ‘such conceptions of incompleteness could enrich the practice of social science and the humanities in Africa and globally’. He advocates a ‘convivial scholarship’ which challenges labels that ‘oversimplify the social realities of the people, places and spaces it seeks to understand and explain’, which recognises ‘the importance of interconnections and nuanced complexities’, and which ‘sees the local in the global and the global in the local by bringing them into informed conversations, conscious of the hierarchies and power relations at play’.4 In focusing on (only) about 20 of the 68 or more languages spoken by the world Jane Eyre, and, for each of them, zooming in on only a few especially interesting or indicative translations, we have made the incompleteness of our project obvious. In this way, we assert the importance of recognising that the world Jane Eyre can never be fully known. It is possible to enter into, explore and sample the phenomenon, but not to possess it. It is true that I (Matthew Reynolds) have had what might be called a controlling interest in the project; I initiated and led it; I have edited the essays by my co-authors, and I have written the sequence of chapters that offer a grounding and summation of the research. Some sort of unifying propulsion was necessary for the work to have any coherence. But, at each stage, I have tried to open that propulsion to re-definition and re-direction by my co-authors (hence their being co-authors rather than contributors). I proposed a selection of passages, linguistic features and key words that we might look at together across languages in our practice of collaborative close reading, but that selection changed following input from the group. So also did the structure of this volume. The maps, constructed by Giovanni Pietro Vitali, present data that has been contributed by all the co-authors (and indeed many other participants in and friends of the project, as described in the Acknowledgements). Likewise, the translingual close-readings that I perform in Chapters IV–VII build on observations made by many of the co-authors, and others; as do the arguments about location that I make in Chapter III, and the conceptualization of translation that I offer in Chapters I and II. In writing these chapters, I have tried to honour and perform this plural authorship, shifting between the ‘we’ of the project and the ‘I’ of my own point of view, and opening up a dialogue with my co-authors. That conversation continues on a larger scale across the volume as a whole, in the interplay between the chapters and the essays, and between the written analyses and the visualisations. This dialogic structure embodies our conviction that the heterolingual and multiplicitous phenomenon of the world Jane Eyre cannot be addressed by translating it into a monolithic explanatory framework and homolingual critical language. While they meet in the comparative unity of this volume, and the shared medium of academic English, the readings, with their different styles, emphases, rhetorics and points of reference open onto a convivial understanding of differences, interconnections and complexities — they aim to generate Nyamnjoh’s ‘informed conversations’. Correspondingly, we have very much tried to avoid the imposition of pre-formatted labels onto our material. In the convivial progress of our research, the author of each essay was free to pursue whatever line seemed most interesting to them in their context, while our understanding of all the categories that organise our work, from ‘a translation’ (see Chapters I and II) to ‘an act of translation’ (see Chapter III) to ‘language(s)’ (see Chapter II) developed in response to the texts and situations we encountered.

Our work is also, of course, in dialogue with prominent recent voices in the anglophone and European literary academy. With Pascale Casanova, we rebut ‘le préjugé de l’insularité constitutive du texte’ [the assumption of the constitutive insularity of a text] and set out to consider the larger, transnational configurations through which it moves5 — though recognising, more fully than she does, that such configurations can never be known in their entirety, and that circulation can happen in intricate and unpredictable ways. We follow Wai Chee Dimock in realising that, not only ‘“American” literature’, but any literature is ‘a crisscrossing set of pathways, open-ended and ever multiplying, weaving in and out of other geographies, other languages and cultures’;6 and we agree with Dipesh Chakrabarty in paying ‘critical and unrelenting attention to the very process of translation’.7 Our conception of translation builds on research that has been published in Prismatic Translation (2019), which in turn is indebted to the work of many translation scholars — debts which are noted both there and here, throughout the pages that lie ahead. Prismatic Jane Eyre as a whole enacts in practice an idea of prismatic translation (briefly put, that translation inevitably generates multiple texts which ask to be looked at together), but what that means in theory can be conceived in different ways. Of what is to come, Chapter I develops the prismatic approach in dialogue with the essays in this volume, and with theorists writing in English, Italian and French; Essay 1, by Ulrich Timme Kragh and Abhishek Jain, offers a somewhat different conception, drawing on Indian knowledge traditions and theories of narrative and translation in Sanskrit and Hindi; Essay 8, by Kayvan Tahmasebian and Rebecca Ruth Gould, articulates its argument through Persian conceptions of genre; while Andrés Claro, in Essay 5, takes as his starting point what he calls ‘a critical conception of the different possible behaviours of language as a formal condition of possibility of representation and experience’. This plurality of points of view is a crucial element in our practice of convivial criticism. What Prismatic Jane Eyre offers is, not a variety of material channelled into a single explanatory structure, but rather a variety of material explored in a range of ways from different theoretical perspectives. It is in this respect that the work we present most differs from that of the figure in the European and North American academy who has most energised this project: Franco Moretti. We have learned from Moretti’s ambition to invent techniques for criticism with a wide transnational scope, and in particular from his use of cartography; but we differ decisively from his conviction that world literature can be mapped according to a single explanatory schema, a ‘world system’ with an inescapable ‘centre’ and ‘periphery’. Most of all, we depart from his view that close reading can have no place in the study of world literature, and that ‘literary history will … become “second-hand”: a patchwork of other people’s research, without a single direct textual reading’.8 This volume rebuts that assertion. To read closely means to attend to particularities: of individual style; of linguistic repertoire; of ideological commitments; of historical and geographical location. As I explain further in Chapter IV, and as will be evident throughout this volume, attending to particularities means doing something that is fundamental to world literary study: recognising and responding to difference.

Prismatic Jane Eyre is open to being explored in various ways. This ‘Introduction’ is really only the first section of a serial discussion which continues through Chapters I–VIII, in which I offer an account of Jane Eyre as a world work, addressing successively the theory of translation, conception of language(s) and idea of location that arise from it (Chapters I–III) before presenting a manifesto for multilingual close reading, with examples (Chapters IV–VII), and finally offering some conclusions (Chapter VIII). These chapters are in dialogue with the essays by which they are surrounded, which focus on particular contexts and issues. Each chapter serves as an introduction to the essays that follow it, and the sequence of the essays represents an evolution of theme. Those following Chapters I and II speak most immediately to the conceptualisation of language(s), translation and text. Ulrich Timme Kragh and Abhishek Jain, in ‘Jane, Come with Me to India: The Narrative Transformation of Janeeyreness in the Indian Reception of Jane Eyre’ offer a redefinition of the prismatic approach, drawing on knowledge traditions in Sanskrit and Hindi, before presenting an account of the interplay between translations and adaptations of Jane Eyre in many Indian languages. Paola Gaudio, in ‘Who Cares What Shape the Red Room is? Or, On the Perfectibility of the Source Text’, traces variants between successive English editions of Jane Eyre, and discovers how they have played out in Italian translations, showing that ‘the source text’ in fact consists of texts in the plural. In ‘Jane Eyre’s Prismatic Bodies in Arabic’, Yousif M. Qasmiyeh takes an Arabic radio version as the starting point for his argument that Jane Eyre is crucially an oral as well as a written work, and that this feature becomes especially charged in Arabic translations; while, in ‘Translating the French in the French Translations of Jane Eyre’, Céline Sabiron shows how French translators have been puzzled by the French that was already present in the language Brontë wrote.

The essays following Chapter III have most to do with location. In ‘Representation, Gender, Empire: Jane Eyre in Spanish’, Andrés Claro finds radical differences between the translations done in Spain and in hispanophone South America; while, in ‘Commissioning Political Sympathies: The British Council’s Translation of Jane Eyre in Greece’, Eleni Philippou showcases one particularly charged translation context from the Cold War. In ‘Searching for Swahili Jane’, Annmarie Drury investigates why Jane Eyre has not been translated into Swahili (and hardly at all into any African language); and, in ‘The Translatability of Love: The Romance Genre and the Prismatic Reception of Jane Eyre in Twentieth-Century Iran’, Kayvan Tahmasebian and Rebecca Ruth Gould demonstrate how a combination of place and political moment impart a distinctive generic identity to translations in late twentieth-century Iran.

The essays following Chapters IV and V, and interspersed by Chapters VI and VII, offer the most tightly focused close readings. After Chapter V’s discussion of ‘passion’ in many languages, you will find Ana Teresa Marques dos Santos and Cláudia Pazos-Alonso’s essay on ‘A Mind of her Own: Translating the “volcanic vehemence” of Jane Eyre into Portuguese’, Ida Klitgård’s on ‘The Movements of Passion in the Danish Jane Eyre’, and Paola Gaudio’s on ‘Emotional Fingerprints: Nouns Expressing Emotions in Jane Eyre and its Italian Translations’. After Chapter VI’s investigation of the many meanings of ‘plain’ come Yunte Huang’s essay on ‘Proper Nouns and Not So Proper Nouns: The Poetic Destiny of Jane Eyre in Chinese’, Mary Frank’s on ‘Formality of Address and its Representation of Relationships in Three German Translations of Jane Eyre’, and Léa Rychen’s on ‘Biblical Intertextuality in the French Jane Eyre’. Chapter VII, with its investigation of the distinction between ‘walk’ and ‘wander’ and of what becomes of it in different tongues, its presentation of two ‘prismatic scenes’, and its account of ‘littoral reading’, then opens onto three essays that attend to grammar and perception: Jernej Habjan’s ‘Free Indirect Jane Eyre: Brontë’s Peculiar Use of Free Indirect Speech, and German and Slovenian Attempts to Resolve It’, Madli Kütt’s ‘“Beside myself; or rather out of myself”: First Person Presence in the Estonian Translation of Jane Eyre’, and Eugenia Kelbert’s ‘Appearing Jane, in Russian’. After which, you will find some conclusions (Chapter VIII), information about the lives of some of the translators discussed, a list of the corpus of translations that we have worked from, and a link to the code that underlies the interactive maps and JavaScript animations.

Structured as it is by this sequencing of the chapters and essays, the volume has not been formally divided into sections, whether by theme or (for instance) by region, because to do that would be to impose exactly the kind of artificial neatness denounced by Nyamnjoh: close reading can be found in all the essays, as can attention to place and to the conceptualisation of the processes in play. The chapters are, in a sense, written by ‘me’ (Matthew Reynolds); but in writing them I am endeavouring to speak on behalf of the whole collaborative project, so the narrative voice shifts between more plural and more individual modes. The essays embody more consistently the distinctive styles and approaches of their authors.

Prismatic Jane Eyre is also represented by a website. Depending on when you are reading these words, the website may still be live at https://prismaticjaneeyre.org/, or it may be archived at https://web.archive.org/web/20231026144145/https://prismaticjaneeyre.org/. In either form, the website offers a quick way of sampling the project as a whole. What follows in this volume is obviously very much fuller, and perhaps it may seem a lot to read through from beginning to end. We invite you to follow the sequence of chapters and essays if you wish; but we invite you equally to hop, skip and wander as you will. Prismatic Jane Eyre offers, not the encapsulation of a phenomenon, but an opening onto it; and we hope that you, as a reader, may relish entering this incomplete exploration of Jane Eyre as a world work, just as we, as readers, and as writers of readings, have done.

Works Cited

Casanova, Pascale, La République mondiale des lettres, new edition (Paris: Seuil, 2008).

Cayley, John, Programmatology, https://programmatology.shadoof.net/index.php

Chakrabarty, Dipesh, Provincializing Europe Postcolonial Thought and Historical Difference, new edition (Princeton, NJ.: Princeton University Press, 2008), https://doi.org/10.1515/9781400828654

Glissant, Edouard, Poétique de la relation (Paris: Gallimard, 1990).

Moretti, Franco, Distant Reading (London: Verso, 2013).

Nyamnjoh, Francis B., Drinking from the Cosmic Gourd: How Amos Tutuola can Change our Minds (Mankon, Bamenda, North West North West Region, Cameroon: Langaa Research & Publishing CIG, 2017), https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctvh9vw76

1 Franco Moretti, Distant Reading (London: Verso, 2013).

2 John Cayley, Programmatology, https://programmatology.shadoof.net/index.php

3 Edouard Glissant, Poétique de la relation (Paris: Gallimard, 1990), p. 33.

4 Francis B. Nyamnjoh, Drinking from the Cosmic Gourd: How Amos Tutuola can Change our Minds (Mankon, Bamenda, North West Region, Cameroon: Langaa Research & Publishing CIG, 2017), pp. 2, 5.

5 Pascale Casanova, La République mondiale des lettres, new edition (Paris: Seuil, 2008), p. 19.

6 Wai Chee Dimock, Through Other Continents: American Literature across Deep Time (Princeton, NJ.: Princeton University Press, 2006), p. 3.

7 Dipesh Chakrabarty, Provincializing Europe Postcolonial Thought and Historical Difference, new edition (Princeton, NJ.: Princeton University Press, 2008), p. 17.

8 Moretti, Distant Reading, pp. 48–49.