1.4.3 Europe’s Other(ed)s: The Americas, Africa, Asia, and the Middle East in Contemporary History (ca. 1900–2000)

© 2023 Lima, Ozavci, Sipos, and Wagner, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0323.12

Introduction

The twentieth century saw both the heyday and decline of European dominance across the globe. At the beginning of the century, European empires (joined by the United States and Japan) controlled nearly eighty-five percent of the world’s land mass, but after two devastating global wars in the space of a few decades, many of the societies that had been subjugated by these empires became independent. The rise of a bipolar world order after 1945 replaced many of the old colonial linkages, but justifications for decades of European expansionism did not entirely disappear during the course of the century. What endured was the idea of civilisation, the positivist and hierarchical system of international law, and various processes of ‘othering’ that had unfolded at least since the 1770s. European societies continued to cling to their own systems of truth and narrative, considering their supremacy almost natural and a product of innate qualities. To justify this narrative in the twentieth century Europeans created, as in previous centuries, long-lasting ideational structures in relation to other communities and polities of the world.

Africa

During the twentieth century, the relationship between the European ‘self’ and the African ‘other’ does not appear to have significantly changed from that of previous centuries. In his Lectures on the Philosophy of World History, given between 1822 and 1830, the German philosopher Friedrich Hegel (1770–1831) wrote that Africa “in itself holds no particular historical interest, except for the fact that men live there in barbarism and savagery, devoid of civilisation [...] it is a childlike country, enveloped in the darkness of night.” This was a fairly representative view for the nineteenth century. In the twentieth century, similar views are still present in the European imagination. For example, as recently as 5 July 1998, the Spanish newspaper ABC argued that “[African] decolonisation was premature, and the forms of nationalism created were something akin to placing a loaded bomb in the hands of a child. [...] Mentoring is required for these child-minded people and their leaders.”

The dissolution of European empires over the course of the twentieth century evidently changed Europe’s relationship towards the African continent. The process of political decolonisation represented a new stage in their relations, although there were still attempts by European colonisers to maintain control by modifying certain rules in the colonial system. The colonial powers, according to Frederick Cooper, also sought to domesticate the new social forces unleashed by decolonisation through more ‘friendly’ policies of development and stabilisation. Thus, these new political ties did not imply a profound change in the perception of Africa from the European perspective, as the examples below show.

There are at least three central imaginary constructions in relation to Africa that have persisted until today. The first is the ‘Africa of Misery’, focusing on extreme poverty and instability, as well as famine, sexual violence, and a lack of basic sanitation on the continent. This image goes beyond an economic perspective and enters the sphere of morality: Africans do not have ‘things’ (they are ‘underdeveloped’), because they supposedly lack the capacity to manage their own wealth, whether as a result of geography, climate, or social and historical issues. As such, they are often visually represented as nude, suffering from the ravages of hunger, and inhabiting stark, inhospitable environments. This ‘miserable’ Africa is the chosen land of intervention—military interventions as well as charitable ones by non-governmental and humanitarian organisations. This imaginary underpinned European imperial and colonial ambitions for several centuries and persisted in the twentieth century. An example is the dictatorship of Antonio Salazar (1889–1970) in Portugal, which sought to reinforce, through military power, the role of Europe in the civilising process. Various history books, such as Carlos Selvagem’s Portugal Militar (1926) or História do Exército Português (1945) by Luis Augusto Ferreira Martins, supported this idea by glorifying past military actions in the colonial wars. Another, contemporary, example of this image of African people as ‘underdeveloped’ is the Spanish chocolate brand Conguitos, which features a naked, infantilised cartoon character with bulging eyes and lips (see Figure 1).

Fig. 1: A package of Conguitos, https://es-gl.openfoodfacts.org/images/products/841/055/600/7873/front_fr.13.full.jpg.

The character also reflects the second imaginary construct, which involves the infantilisation of African people. According to this image, the African continent represents the ‘infancy’ of humanity, while Europe in contrast has advanced to the ‘adult’ stage. The famous Belgian comic book series The Adventures of Tintin, created in the 1930s, includes a revealing example of this process of infantilising the African other. The second volume, Tintin in the Congo (1931), displays a paternalistic vision of Africa, particularly of the Congo, whose inhabitants are presented as primitive, barbaric and uncivilised. They are “grateful” for the presence of the colonisers, who appear to bring forth progress and development in their societies, for example through medicine or education. In one particularly controversial scene in the book, a Congolese woman who is grateful to the white protagonist Tintin for healing her husband, exalts him with the exclamation: “white man [is] very great!” While Europeans—always white men—are portrayed as heroes, non-white people are portrayed in a patently offensive and racist way: they are passive, submissive, and in need of care, akin to children.

The third imaginary construct is that of the ‘exotic Africa’, characterised by its natural parks, animals (typically lions, leopards, giraffes, elephants, and so on), as well as its ‘exotic’ culture and natural landscapes. According to this construct, Europe must assume responsibility for preserving Africa’s natural environment, through the intervention of numerous NGOs, by conserving natural resources and promoting ‘true’ development. In this sense, Africa has become an emblematic example of the contradictions that exist in Western discourses on environmental preservation, development and the defence of human rights. In reality, these imaginaries are ways of deconstructing the dignity of the other and, upon closer analysis, what becomes evident is that projects disguised as ‘humanitarian’ initiatives or other ethical justifications are in effect acts of violence towards the other.

The Middle East

Unlike Africa, there is much uncertainty today as to where one can geographically locate the Middle East and how we might think of the societies that inhabit it. What is widely accepted is that the term ‘Middle East’ was invented by Anglo-American strategists as a semantic and geographical category at the turn of the twentieth century, possibly in relation to the Boxer War (1899–1901) in China, which constituted the so-called Far Eastern Question for Western European actors. In other words, from its inception the term ‘Middle East’ described an entire region through geographical reference to Europe. It was defined through a Eurocentric perception of the globe. Politically, culturally and economically it also helped identify Europe through a process of ‘othering’—categorising and hierarchising groups of people, often implicitly but sometimes disdainfully overtly—which superficially associated the West with progress, civilisation, and development, and the Middle East with the binary opposites of those categories.

The term ‘Middle East’ thus symbolised how a handful of leading-edge Western (European) empires had assumed managerial responsibilities to govern the world, redraw its maps and define the inhabitants of its diverse parts. At the same time, this region proved to be an indispensable source of the most important energy resource in the twentieth century: oil.

At the end of the First World War, the seven-hundred-year-old Ottoman Empire was partitioned by Western European empires in an attempt to secure their strategic and economic interests, since oil had proved to be a viral strategic weapon. The new states in the Levant and Mesopotamia founded out of the ashes of the sultan’s empire were placed under the mandate of Britain and France, which also controlled the oil resources of the region.

The end of the Second World War and the ensuing decolonisation process coincided with the foundation of Israel and a period of rising Arab nationalism, coups d’état, alongside attempts at nationalising the oil industries. In the eventful and fateful history of this region, we can discern at least two turning points where European othering of the Middle East is concerned. The first of these was the Suez Crisis of 1956. The desire of Egyptian President Gamal Abdel Nasser (1918–1970) to nationalise the Suez Canal went against treaties imposed in the nineteenth century by Britain and France. Nasser’s plan was met with ridicule. He was portrayed as “couscous Mussolini” by the Western press. But he also sparked fears that his plan could jeopardise a most important route that brought Middle Eastern oil to the west. Ultimately, the crisis marked the end of Anglo-French dominance in the region, with Egypt managing to meet its ends with the support of the United States and the Soviet Union, which together emerged as the new dominant powers in the region.

A second event that merits attention here is the 1973 oil crisis, triggered when the Organization of Arab Petroleum Exporting Countries (OAPEC) halted oil exports to the United States and the Netherlands in an attempt to negate Western and European support to Israel during the Arab Israeli War of the same year. The resulting paralysis impacted gravely on the Western economies of the time. It demonstrated that Middle Eastern countries had become existential sources of political and economic vigour and stability in Europe, not to mention its post-war recovery. Establishing cordial relations with Middle Eastern leaders and helping them secure their dynastic regimes—even if they were militarist, ultra-religious or ultra-nationalist, totalitarian or authoritarian—became a prerequisite for maintaining immediate European interests.

The countries of the Middle East have indeed proven to be some of the most conflict-laden, undemocratic and politically turbulent neighbours of Europe ever since the term Middle East was coined at the turn of the century. But the Middle East was not simply Europe’s other. All of its problems, past and present, have been by-products of the complex strategic and economic relations between Western European empires and the region’s local inhabitants. Even to this day the issues of the Middle East are seen in European popular culture through a myopic lens, which obscures these entangled imperial histories and eclipses the fact that the tragedies of the region are also products of global connections.

Asia

European images of Asia have changed dramatically over time. In the nineteenth century representations of China, for example, shifted from a civilised ‘Europe of the East’ to an ancient country ‘without history’, or even to an evil ‘yellow peril’. As Europe’s ‘other’, Asia provided mirror images that helped foster a sense of European identity. The Asian present has appeared both as an envisioned European future and as a perceived European past; as a symbol of progressiveness or backwardness. Similarly, twentieth-century images of Asia were represented in temporal metaphors that posited Europe as Asia’s yardstick. These perceptions of Asia oscillated between anti-communist fears of an ‘Oriental despotism’, grand hopes of Westernisation and democratisation, and disillusionment with idiosyncratic paths to modernity.

After the First World War, when European ideas of political order, monarchic and liberal alike, were in a state of crisis, the Asian continent appeared to be a source of both inspiration and threat. The Paris Peace Conference (1919–1920) revealed that Asia was still perceived as part of the European sphere of influence. In an act of great power politics the Western nations decided to hand over Qingdao, then a Germany colony in China, to Japan instead of returning it to Chinese sovereignty. The May Fourth Movement (1919), a political protest movement that erupted in China in response to its treatment as a bargaining chip by foreign powers, paradoxically called for Westernisation as a means of modernisation. At the same time, some European writers regarded the First World War as having undermined the traditions of European intellectual thought, finding new inspiration in Chinese Daoism. Other European intellectuals, like the German sociologist Max Weber, conceived of Asia as Europe’s religious and cultural ‘other’ in order to explain why modern capitalism had only emerged in Europe itself. The Russian Revolution (1917), on the other hand, became another seminal moment that had a severe impact on perceptions of Asia in Europe. Early nineteenth-century notions of an ‘Oriental despotism’ re-emerged after the Soviet Union had established a communist dictatorship throughout Eurasia, along with rising fears of westward Soviet expansion that could threaten the fragile political order of interwar Europe. Insulating Europe from revolution thus motivated an Allied intervention in the Russian Civil War (1917–1922).

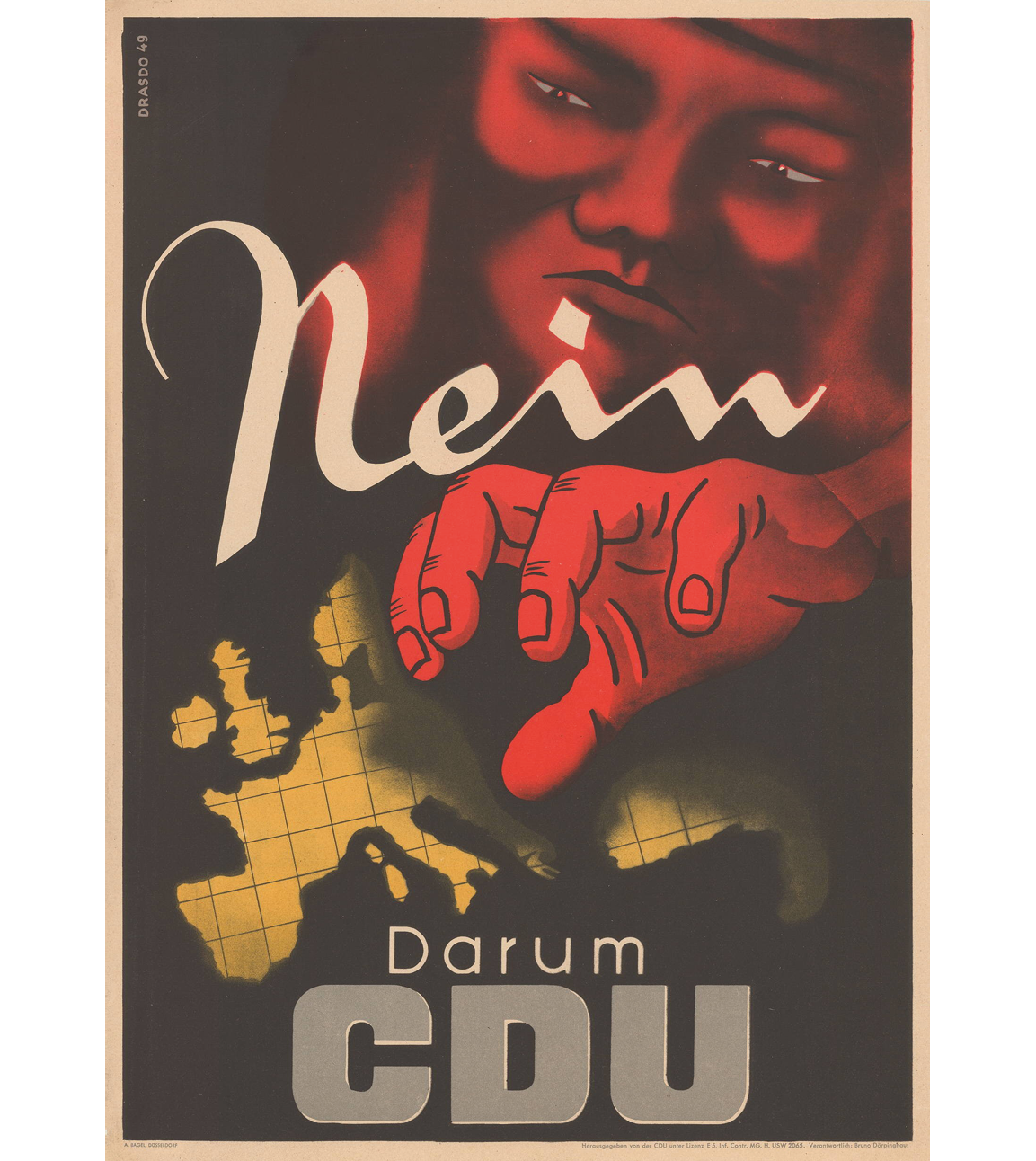

After the Second World War, older assumptions about Europe’s relationship with Asia were both strengthened and challenged by Cold War divisions in Europe, which split the continent into two opposing political systems. With a socialist bloc emerging on its eastern edge, the idea of ‘Europe’ as a liberal realm seemed to diminish, whereas communism was on the rise. In Western Europe (and the United States), an anti-communist ‘red scare’ was built on older narratives of the dangerous and evil east. In August 1949, a few months before China would also turn communist, the conservative Christian Democratic Union of West Germany portrayed a gloomy, Asian-looking Bolshevik seizing hold of Europe; an innocent Europe that was to be defended by conservative values (see Figure 2). Left-wing intellectuals in Cold War Western Europe, on the other hand, were inspired by communist China as an alternative to both Western capitalism and Soviet socialism, though they largely neglected to speak of the millions of Chinese who were victims of starvation. Paradoxically, Mao became a symbol of domestic protest among parts of European youth rebelling against older generations that were perceived to run a repressive state.

Fig. 2: ‘Nein…Darum CDU’ [‘No… That’s why CDU’], poster of the Christian Democratic Union of Germany for the West German federal election, August 1949, CC BY 3.0, DE: Landesarchiv Baden-Württemberg, Abt. Staatsarchiv Freiburg, W 110/2 Nr. 0144: https://www.europeana.eu/de/item/00733/plink__f_5_171148.

The collapse of the Soviet Union and the end of the Cold War sparked grand hopes of Asia’s democratisation, understood as Westernisation, among European intellectuals. These were proven to be ill-founded relatively quickly. In the case of China, the Tiananmen Square Massacre in 1989 engendered disillusionment with Beijing’s path to liberal modernity, which many European observers had envisioned as being free of repression. In response to new anti-Chinese sentiments in Europe, Chinese writers claimed that “China can say no” to the political, economic, and cultural hegemony of Western powers. The Russian Federation, on the contrary, initially turned into a democratic system after 1991, endorsing European self-perceptions of being on the right side of history. In 2005, President Putin even declared that “Russia was, is and will, of course, be a major European power.” But after Russia annexed the Crimean Peninsula and waged a military conflict in eastern Ukraine in 2014, both Russian and European politicians referred to the Russian Federation as a political entity outside Europe. Again, Russia became Europe’s ‘other’, a foil that fostered a European self-affirmation of liberalism, democracy, and rule of law.

United States of America

When the American Army arrived in Europe in 1917 and played a decisive role in the outcome of the First World War in 1918, Europeans could see for themselves that the United States of America had become a world power. Simultaneously, American companies became vital participants in European economic life, while European cultural life was beginning to be reshaped by American feature films, as well as jazz music. Another channel of this transatlantic influence was formed by a multitude of American tourists that visited Europe in the 1920s, where they were received as rich people on a poor continent: in many European countries, young, American, female tourists were described as ‘Miss Dollar’.

American economic and cultural influence sparked fears on both sides of the political spectrum over America’s ‘cultural imperialism’ and its ‘economic colonisation’ of Europe. Both right-wing and left-wing observers thought that their homelands had lost part of their sovereignty due to the effects of American popular culture and consumerism. They felt that these phenomena had changed European attitudes to the extent that millions of Europeans had been ‘Americanised’. For example, it was lamented in the conservative British newspaper Daily Express in 1927 that the consumption of Hollywood movies had turned millions of British people into “temporary American citizens”. The criticism of specific attributes of American power, even when it used negative stereotypes, should not be confused with anti-Americanism, since many critics did not regard America as ‘evil’ or an ‘enemy’. During the interwar period and the 1950s, conservative critics emphasised the supposed egoism and materialism of the Americans, in contrast to the cultural superiority of Europe—but they also accepted the democratic political regime and the economic system of the US. These critics were afraid of American gender relations, too, because the modern American woman was said to be hedonistic and powerful, and this type of woman might have been dangerous for traditional family values.

The anti-Americanism of the extreme right was rooted in chauvinistic nationalism and a phobia of the ‘Americanisation’ of Europe and the wider world. For example, the National Socialists in Germany asserted that the US was founded and governed by Jewish and African American people who were racially ‘inferior’. This approach contrasted American modernism and internationalism with national traditions and the homely atmosphere of the motherland. The anti-Americanism of the extreme left characterised the ‘non-democratic’ US as the leading state of capitalist exploitation, oppression, colonialism (see Figure …), and consumer culture, where everything was ‘for sale’ and culture was degraded to a common commodity. While this version of anti-Americanism already existed in the interwar period, it strengthened and spread through Europe after the Second World War. Jazz, for example, was banned in some socialist countries until the late 1950s and early 1960s because it was regarded as the music of the imperialist US. Later, however, jazz found clearer expression as the music of the oppressed African Americans.

Other Europeans, however, regarded the US as the model for modernisation in Europe. Their Americophilia had a one-sided focus: the US was characterised as a veritable paradise on earth with its high standards of living and ‘unbounded possibilities’. From this perspective, jazz was a means of cultural democratisation: it bridged the gap between elite and popular culture, since it was popular dance music for all social classes and seen as a symbol of modernisation.

Although these different sentiments towards the US were mostly consistent during the twentieth century, their acceptance shifted over time, from country to country, and between age groups. For example, just after the Second World War, the scientific prestige of America increased immensely thanks to the financial possibilities offered by American research institutions and the great number of European scientists who had moved there. During the 1960s and 1970s the Vietnam War shaped European perceptions of the US more negatively, because the conflict appeared to evidence an American imperialism which was dangerous to Europe too. Later, in the early 1980s, only ten percent of Europeans identified as anti-American, while thirty percent were pro-American and the majority were neutral. But in the Netherlands, for example, young people showed much more positive attitudes toward the US than old people did. Italians trusted US foreign policy more than the French people, while anti-American rhetoric was popular enough for the Panhellenic Socialist Movement (PASOK) to win two general elections in Greece in the 1980s.

Latin America

European scholars often approach the countries of Latin America as a relatively homogeneous bloc, assuming their national identities to be rooted in the shared colonial past and associated Spanish and Portuguese heritage. Simplistic references to ‘Latin America’ exclude strong legacies of Amerindian and African communities in the history and culture of these nations; such legacies include the name ‘Abya Yala’, the denomination of the American continent of the Kunas (Panama) prior to the European conquest and a term currently adopted by many indigenous communities as a counter-hegemonic designation for the continent. Although the region’s countries were for several centuries ‘dependent’ on foreign powers and organisations, it is clear that the twentieth century initiated a new stage in relations between Europe and Latin America, especially after the two World Wars.

During the first decades of the twentieth century, Latin American countries embarked on a profound reflection on their identities. Brazil, for example, did so through the modernist movement. One document that represents the thinking of this movement is the Anthropophagic Manifesto, published in 1928 by the Brazilian poet Oswald de Andrade (1890–1954). The manifesto claimed a form of avant-garde art that sought to “cannibalise the European spirit” (referring to anthropophagic rituals) and unite this legacy with that of indigenous and African communities, in order to establish a “true” national identity. This search for a new identity took place in the context of the declining European hegemony after the First World War. Some decades later, during the Second World War, Latin America achieved greater autonomy to make independent negotiations with world powers such as Germany, the United States, or Spain. The politics of Argentinian President Juan Domingo Perón (1895–1974), or the Brazilian leader Getúlio Vargas (1882–1954), are clear examples of a more autonomous diplomacy in this period. This development paved the way for a new period of relations between Europe and Latin America in which Europe came to see the Latin American nations as more ‘equal’ to itself.

However, certain former imperial metropoles attempted to revisit symbols of the colonial past in order to forge new relationships with their former colonies. For example, during the years of General Francisco Franco’s regime, Spain considered ‘Hispano-America’ to be a part of its nationalist ideological project, as it sought to recover symbols of the past such as Catholicism, the Castilian language, imperialism, and the “historical unity of Spain and Latin America”. The aim was to form a kind of spiritual community (the ‘Hispanic race’), which was to include Latin American countries. Portugal, on the other hand, given its relatively weak economic and political position, for much of the twentieth century stood in the shadow of its former colony, the immense Brazil. Whereas stereotypes of Brazil may previously have revolved mainly around its image as the country of football, carnival, samba and exotic nature, by the end of the twentieth century it was one of the world’s major economic powers, and in the first decade of the twenty-first century it joined the bloc of major emerging national economies known as BRICS: Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa.

Thus, while Europe might view Latin America as a continent facing diverse challenges, such as economic and social inequality, violence in urban centres, corruption, and authoritarian governments, its nations have also come to be viewed as promising—“the emerging Latin America”. This is particularly evident in a number of developments in the twentieth century and at the beginning of the twenty-first: high rates of economic growth, foreign direct investment, a growing middle class, scientific development, and greater political relevance on the international scene.

Conclusion

The ‘other’ and othering have always been open-ended discursive practices, devoid of fixed content. They have been operationalised in the European imagination, while rarely corresponding to historical reality, in order to justify colonial or neo-colonial control. They have thus held different functions and connotations at different moments in time and with regard to different continents and regions, making it difficult to explain their workings precisely. However there is perhaps one exception: othering has clearly helped Europe style itself as the exceptional continent, distinguished from the rest. Despite the decline and collapse of European empires, this did not change fundamentally during the twentieth century. In political discourse, popular culture, and international relations, Europeans still often referred to stereotypes such as infantile Africans, despotic Orientals or even consumerist Americans to describe the world, defining themselves as superior in the process. Responding to the shifting global geopolitics of the twentieth century, old fears of invading barbarian hordes were updated as red scares or visions of ‘Coca-Colonisation’, but still they served the same purpose of characterising European civilisation as the model for the world.

Discussion questions

- What are the differences and similarities between Europeans’ images of other continents in the twentieth century?

- These images changed over the course of the twentieth century. What, according to the text, were the reasons for this change?

- Are these images still prevalent in the twenty-first century? How have they changed?

Suggested reading

Amorín, Alfonso Iglesias, ‘Discurso y memoria de las guerras colonials africanas en las dictaduras de Franco y Salazar’, Ler História 79 (2021), 191–213.

Bessis, Sophie, Occidente y los otros: Historia de una supremacía (Alianza, Madrid, 2002).

Bethell, Leslie, ‘Brazil and Latin America’, Journal of Latin America Studies 42 (2010), 457–485.

Cooper, Frederick, Africa since 1940: The Past of the Present (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002).

Davison, Roderic H., ‘Where is the Middle East?’, Foreign Affairs 38:4 (1960), 665–675.

Grazia, Victoria de, ‘Mass Culture and Sovereignty: The American Challenge to European Cinemas, 1920–1960’, The Journal of Modern History 61:1 (1989), 53–87.

Koppes, Clayton R., ‘Captain Mahan, General Gordon, and the Origins of the Term “Middle East”’, Middle Eastern Studies 12:1 (1976), 95–98.

Mühlhahn, Klaus, Making China Modern: From the Great Qing to Xi Jinping (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2019).

Smith, Steven K. and Douglas A. Wertman, US–West European Relations During the Reagan Years: The Perspective of West European Publics (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 1992).