3.1.3 State-building and Nationalism in Contemporary History (ca. 1900–2000)

© 2023 Almagor, Koura, Kurdi, and Pan-Montojo, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0323.27

Introduction

Over the course of the twentieth century, the definition and the relevance of the nation-state—and related topics, such as citizenship and diaspora—changed dramatically in Europe. However, while the devastation of the First World War and the Second World War as well as the tensions of the Cold War and European integration did much to challenge the autonomy of the nation-state, it remained the norm in international politics. At the same time, the development of the welfare state after 1945 introduced new ideas of citizenship.

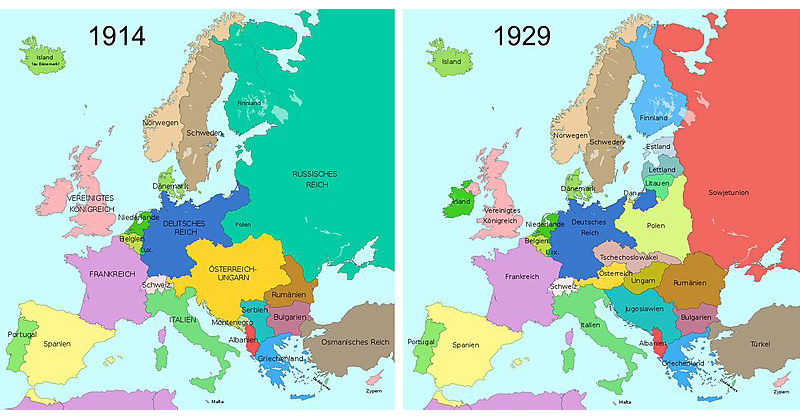

Fig. 1: Beat Ruest, Europe before and after the First World War, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Europa_1914_1929_quer.jpg.

These parallel maps reveal the transformation of European empires before and after the First World War. Most prominent changes include the dissolution of Austria-Hungary into the nation-states of Austria, Hungary, and Czechoslovakia, the conglomeration of Serbia, Montenegro and other lands of the former Austria-Hungary into the Kingdom of Yugoslavia, and the creation of Poland, Lithuania, Latvia, Estonia and Finland out of territories previously controlled by the Russian empire.

The Nation-State, Minorities, Diaspora

In many ways the nation-state was an invention of the long nineteenth century. The various national movements of that period rapidly turned this novel idea into mainstream political reality. As a result, by the start of the twentieth century, the notion that every nation—every ‘people’—was entitled to its own politically autonomous geographical territory had become the main driving force of politics. Nationalists, who argued that their nations had experienced long-running minority status in various imperial settings, reinforced their demands for their own nation-states. While neither nations nor states were new, the nation-state was an innovation on the model of the multinational kingdoms and empires that had dominated the map of Europe for centuries. In order to understand how this political make-up shifted in the twentieth century, it is important to consider the nation-state as a third entity, formed from the ‘state’ (a political unit) and ‘nation’ (a social group that understands itself as an actual or potential sovereign community). Except for ethnically diverse states without aspirations for mono-ethnicity, such as France, Spain, the United Kingdom, and Belgium, many of the newer European nation-states in the twentieth century had one crucial defining feature: they strove to be ethnically homogeneous. In theoretical terms, every nation-state was to be inhabited by the members of only one ethnic nation.

Realities were different. As the century commenced, much of Europe still consisted of empires. The Habsburg Empire, the German Empire, and the Russian Empire controlled much of the continent. On the edge of Europe, the crumbling Ottoman Empire still exerted influence, especially in the Balkans. Ireland was part of Great Britain. All in all, therefore, most political units in Europe were multi-ethnic in 1900. Nevertheless, these multinational empires were under constant pressure until they finally collapsed in the wake of the First World War. For many, 1918 marked a moment of much-needed change, a ‘clean state’ on which Europe could be remade to fit ethno-political desires. American President Woodrow Wilson (1856–1924) popularised the ideal of “national self-determination” amongst various ethnic groups that now saw an opportunity to demand statehood.

The break-up of empires, however, did not automatically reveal geographical units that could be directly shaped into states. Many regions were ethnically mixed, and this created tensions between different nationalist groups vying for political control of the same territories. Nevertheless, following the disintegration of the Russian Empire, several new states emerged in Central and Eastern Europe: Finland, Lithuania, Latvia, Estonia, and Poland. A short-lived Ukrainian state also existed during the Russian Revolution. The end of the Habsburg Monarchy paved the way to full sovereignty for Czechoslovakia and Hungary, with Austria becoming an independent republic. Serbia unified with Montenegro and obtained the former Austrian and Hungarian territories of Slovenia, Croatia, and Bosnia-Herzegovina, together forming the Kingdom of Yugoslavia. In overseeing the drawing of these new borders, geo-strategic and political considerations often turned out to be more important than the ideal of an ethnically homogeneous nation-state. After all, Germany had to be curtailed and the Bolshevik threat contained, or so the Allied powers believed. As a result, when the dust settled on the new constellation of Europe, 32 million people found themselves as ethnic minorities in nation-states, as opposed to the 50 million who had lived as minorities in imperial settings before 1914. Amounting to one third of the population of Central and Eastern Europe, these groups now tended to have fewer rights than before.

In this context it is pertinent to draw a clear distinction between ethnic minorities and the closely related, yet essentially different concept of diaspora. Both minorities and diaspora communities are considered part of the ‘nation’. The difference between them is the way in which each group found themselves outside the ‘motherland’. Diasporas are formed following dispersed migration from a real or imagined ‘mother country’, due to historical cataclysms such as war, famine, persecution, or basic economic necessity. Ethnic minorities mostly gain their status as a result of border alterations. Jews, Armenians, Greeks, Italians, and Irish are considered examples of ‘classic’ diaspora peoples. Romani, Sinti and other traveller communities could also be counted in this category, even though they do not have the same attachment to an ancestral homeland.

As for ethnic minorities in the new nation-states of the early twentieth century, the relations between these communities were aggravated by one of the intellectual innovations of the modern period: racial science. Partially developed in the context of European colonialism in Africa, Asia, and Latin America, the ‘scientification’ of racism provided existing racial prejudices with a veneer of legitimacy. As a result, racism came to co-define intra-European dynamics as well. Defining who was to be counted as a member of an ethnic community had been challenging, as neither nation nor race were grounded in fact. Perceived differences between peoples, which now seemed to be ‘proven’ by science, defined who was termed an insider and who was an outsider to the ‘national body’. In practice, this meant the exclusion of various minorities from newly established societies. This was most notably the case for Jews, who had long been residents of various parts of Europe, in some cases (Poland) for over a millennium.

President Wilson and his followers did not overlook the implications of the gospel of national self-determination for those ethnic minorities that were not able to secure their own states. To protect these minorities, the Paris Peace Treaties of 1919/1920 included several international agreements on minority rights, and the newly established supranational League of Nations devoted much of its efforts to minority rights protection. After all, the four largest newly established nation-states—Poland, Romania, Yugoslavia, and Czechoslovakia—remained heavily mixed societies. Germans represented one of the largest European ethnic minorities. By 1935, ten million ethnic Germans lived across Eastern Europe. Smaller groups resided in Italy, Estonia, and Latvia. Formerly Hungarian Transylvania, now part of Romania, contained three million ethnic Hungarians and a significant number of Serbs. Millions of Jews and Romani and Sinti people formed communities in practically every country in Eastern Europe.

The Second World War meant the definitive end of both the League of Nations and of minority rights. The latter were reconceptualised as human rights, which would come to define the geopolitical agenda for the decades to come. Strikingly, this agenda was shaped by the Western liberal democracies as well as by the USSR. This achievement demonstrated that two different political projects were capable of building common institutions and discourses, when it was deemed mutually beneficial. This common effort culminated in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights of 1948. Despite the momentous significance of the declaration, which ushered in an unprecedented acknowledgement of the rights of individuals, the shift from minority rights to the human rights regime also meant the end of protection for groups that defined themselves beyond the strict confines of the nation-state.

The nation-state itself lost none of its significance after 1945. On the contrary, it remained the norm in international politics, which now also included the decolonising world. The 1948 Declaration implied the existence of nation-states as the pre-condition for the fulfilment of the rights it enumerated. In doing so, with the consent of the big powers, the declaration was contributing to the destruction of colonial empires, accelerated in the 1950s by the growing mobilisation of colonial subjects. At the same time, multi-ethnicity, partially reframed as “multiculturalism” in recent decades, also remained a practical reality across Europe. Even in countries where official nationalist policies had aimed at reshaping cultural realities to obtain a homogeneous people, they did not prevail: Finland retained its Swedish minority, Italy still contains Alto Adige/Südtirol, Belgium consists of two or even three dominant linguistic parts, Switzerland is multi-ethnic and so was Yugoslavia until its dissolution in the early 1990s. Spain has Catalan, Galician and Basque linguistic minorities that support, on different levels, their own national projects.

Ethnic cleansing and coerced demographic alterations before and after 1945 increased cultural and ethnic uniformity in Eastern European countries: the abundant Jewish populations of countries such as Poland, Hungary, Greece and the Baltic states were nearly exterminated during the Holocaust. Roma and Sinti were also targeted by Nazi Germany. After the war, huge demographic groups were expelled from their homelands and relocated elsewhere: Germans were expelled from almost all Eastern countries (Czechoslovakia, Poland, the Baltic states, Romania), Poles were forced to leave the Polish territories ceded to Belarus and Ukraine and were resettled in Pomerania and Silesia. A few years later, many Slavs (Bulgarians, Macedonians) were expelled from Greece during the Greek Civil War.

However, all these massive demographic changes did not lead to perfectly homogeneous communities: for example, there are still Hungarian minorities in Serbia, Slovakia, and Romania, Roma and Sinti live in the whole region, and Turks in Bulgaria. Moreover, in countries such as France, Germany, and the Netherlands (which also have their own historical minorities), the combined effects of decolonisation and the need for guest workers from Turkey and the Maghreb countries led to the influx of various new minorities since the 1960s. African, Latin American and Asian immigration has grown in nearly all European countries since 2000. This tension between the homogeneous underpinnings of nations, as primordialist nationalists and many citizens who share their views understand them, and the realities of multi-ethnic and multicultural societies, is hence highly relevant in most European societies today.

The autonomy of the nation-state has also been challenged by European integration. After the Second World War, the United States of America demanded coordination between Western European states in order to distribute Marshall Plan aid and to strengthen defence mechanisms in view of the Cold War. Another World War had to be avoided at all costs. The creation of the European Economic Community (EEC) in 1957 was only partly the result of these American pressures—it was also underpinned by a long tradition of pan-European projects and utopias. The EEC was also intended to overcome the practical limitations of nationally focussed social and economic regulation, which had proven challenging for Western European governments during the 1950s and 1960s. In the 1990s, after the fall of the Iron Curtain, liberal democracy and Western market capitalism were adopted by the former communist states in their transformation from socialist dictatorship and central economic planning. In the process, these countries also became part of the European integration project. This Europe-wide experiment in regional integration has changed the nature of the nation-state and of state collaboration, creating a type of supra-state—the European Union—consisting of twenty-seven separate states. However, this transformation should not be exaggerated: nation-states have prevailed as basic political units in Europe despite the efforts to limit individual state sovereignty in favour of the supranational institutions of the European Union.

State-building in Europe during the Cold War

How did these various developments surrounding the relatively new concept of the nation-state pan out in the realities of state-building across Europe? Changes in the international system after the Second World War altered the dynamics of the state-building process. The war resulted in the transformation of the world order, in which two superpowers—the United States and the Soviet Union—came to dominate. Both offered entirely different ideological-political and economic models for the European states recovering from the world conflict, resulting in divergent developmental trajectories in the two spheres of influence.

The liberation of East-Central Europe by the Soviet Red Army led to the expansion of the Soviet-style socialist model, by which post-war Eastern Europe was transformed into “people’s democracies”. This terminology suggests a form of democratic parliamentarism, but these ‘democracies’ were in fact dominated by one-party rule, legitimised by Marxist-Leninist ideology. The Soviets imposed the adoption of a political and economic system based on nationalisation, the elimination of private property, collectivisation, censorship, repression, the persecution of political opponents, and restrictions on movement. At the same time, the Soviet model also offered social security, free health care and education, or full employment, which was an attractive alternative to liberal market capitalism. Social equality and the construction of a collective identity weakened the concept of the nation-state in favour of socialist internationalism, emphasising racial equality, the concept of ‘brotherhood’ and, after de-Stalinisation in the 1950s and 1960s, also ‘peaceful coexistence’ between world nations.

However, despite Soviet domination in East-Central Europe, several states tried to find their own paths to socialism and to renew their national sovereignty. An alternative view to adopting the Soviet modernisation model emerged shortly after 1945 in Yugoslavia, which did not join the Eastern Bloc, and later in Albania, which withdrew from it in 1968. Attempts to reform the state socialist regimes in Hungary (1956) and Czechoslovakia (1968) were violently suppressed by the Soviet Army, but a degree of autonomy in foreign policy was allowed in Romania, and in Poland for agricultural matters. Despite attempts at supranational economic and military integration under Soviet supremacy in the form of the Council for Mutual Economic Assistance and the Warsaw Pact, the Soviets were ultimately forced to tolerate the existence of de facto nation-states amongst their satellites.

Unlike in the east, the post-war reconstruction of Europe’s west, south, and north was characterised by continuity rather than by revolutionary change. In these states, including defeated Germany and Italy, liberation from fascism restored a model of democracy based on tradition, continuity, and modernity. Under the control of the United States, this model of liberal democracy and market capitalism was consolidated, and nation-states re-emerged with only minor changes, despite the establishment of an American informal “empire by invitation”. The exceptions to this rule were countries where authoritarian regimes had been built and consolidated in the 1930s, such as Portugal and Spain, or where the threat of a communist victory was used to justify the restriction of democracy and even the imposition of a dictatorship, as had happened in Greece. As for the rest of Western Europe, one of the major changes in response to the challenge of post-war reconstruction was the strengthening of state power, often through the nationalisation of strategic economic sectors such as energy, transport, and public health.

Citizenship

With the consolidation of the nation-state and attendant state-building practices in both Eastern and Western Europe, the question of who exactly was entitled to citizen status within these political units became prevalent. Citizenship is a key concept in modern Western political thought and became one of its most conspicuous elements in this period. The success of the nation-state formula implied that the nation, as a community based on certain levels of formal equality among its members, was now the cornerstone of political organisation. However, the actual meaning of citizenship is plural. In the liberal tradition, citizenship denotes a set of rights and duties that link individuals to political power. By contrast, communitarianism considers citizenship only a result of individual identification with the values of a specific community. Thirdly, republicans find the true basis of a working citizenship in civic practises that are rooted in common moral ground. These three conceptions of citizenship are not fully separate; they intersect with each other and often become entangled in public debates on the nature of the ‘good’ or ‘full’ citizen.

Democratisation, and the value it put on citizenship rights, was not an immediate consequence of the new conditions brought about by the end of the First World War. These developments were challenged by the consolidation of the USSR, but also by the rise of fascism, which radicalised nationalism whilst denying most rights to citizens and excluding different minorities from the nation. Matters changed after the Second World War. In 1950, T.H. Marshall published Citizenship and Social Class, a book that was to give shape to a new history of citizenship based on the acquisition of successive generations of rights. According to Marshall, pressure from below forced states to grant civil rights, then political rights and, finally, social and economic rights to growing portions of the population, developing a more ample and full citizenship under the welfare state, a new device of social integration. This type of state, reaching its most advanced form in the United Kingdom and Sweden, introduced as a general principle that the state should finance a growing bundle of social services (health, education, social insurances) in order to protect all citizens and promote basic equality among them. The welfare state’s progressive narrative was not limited to the West—communist regimes interpreted it in the light of Marxist-Leninist ideology and the subordination of individual rights to collective endeavours. On the other end of the political spectrum, neo-colonialist and developmentalist discourses posited that economic and cultural modernisation, which could impose restrictions on all kinds of rights, was a precondition for democratisation.

The new social movements of the 1960s questioned the inclusiveness of existing citizenship structures. The American civil rights movement condemned the fact that black Americans were excluded from full citizenship status and these debates made their way to Europe as well. Feminists criticised the gender-neutral presentation of citizenship, when in reality the full privilege of this status was only granted to men. Gay and lesbian movements rejected their own legal and social exclusion. Left-wing militants from Berkeley to Paris and Berlin argued that formal rights served to obscure the real authoritarian dynamics that dominated life in businesses, universities, and public offices, as well as the relationship between the West and the Third World. Simultaneously, dissidents in the Eastern Bloc attempted, with scarce results in the short term, to put human rights on the public agenda of communist societies. A contradictory trend emerged as a result of all these forces. On the one hand, rights and political recognition were extended to various groups in various societies. On the other hand, these developments provoked a neo-conservative reaction that rejected the very notion of socio-economic rights, criticising the welfare state for supposedly transforming citizens into overly dependent subjects. At the same time, processes of globalisation have eroded the assumption that rights cannot be separated from state power. The political influence held by various diaspora communities around the world adds to this decline in the central status of the nation-state.

Conclusion

Over the last two centuries, European societies have been organised and shaped by national ideas. During the twentieth century, the concept of the nation-state, nationalism, and minorities associated with this idea underwent significant changes. The disappearance of nationalism and the nation-state had been predicted in the 1990s, but it is now certain that this will not happen, and we can observe opposite trends. Today, we are seeing a radical revision of neoliberal doctrines about the state, which could foreshadow a new kind of state-building. In the age of globalisation, the nation-state is an alternative for many to experience their own national or ethnic identity.

During the twentieth century, we have witnessed the development of a system of human rights, with the result that fewer and fewer rights are linked exclusively to citizenship. Many former nation-states have become multicultural states. The concept of citizenship has changed greatly, mainly due to the challenges of globalisation, technological development and migration, so in the future, belonging to a political nation should not be linked to citizenship.

European states have pursued ethnic and paternalistic policies throughout their twentieth-century history. Some varieties of ethnonationalism are still present in European political life, becoming a tool of manipulating political elites in several countries. Another phenomenon is that certain peoples are stepping out of the nation-state framework to try to define their national identity in the name of a reborn European regionalism.

In the postmodern age, nationalism intensified in many societies in Central and Eastern Europe, while Western and Northern Europe sought to integrate the non-European immigrant masses and eliminate political extremism.

Discussion questions

- What was the impact of the First World War on the role of the nation-state in Europe?

- Did European integration undermine or strengthen the role of the nation-state in the twentieth century?

- Why was the development of the welfare state so significant for the idea of citizenship?

Suggested reading

Blair, Alasdair, The European Union since 1945 (Harlow: Longman, 2010).

Bornschier, Volker, ed., State-building in Europe: The Revitalization of Western European Integration (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010).

Flora, Peter, ed., State Formation, Nation-Building and Mass Politics in Europe: The Theory of Stein Rokkan (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999).

Fulbrook, Mary, Europe since 1945 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001).

Glatz, Ferenc, Minorities in East-Central Europe: Historical Analysis and a Policy Proposal (Budapest: Europa Institut, 1993).

Jarausch, Konrad H, Out of Ashes: A New History of Europe in the Twentieth Century (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2016).

Judt, Tony, Postwar: A History of Europe since 1945 (London: Penguin, 2005).

Motta, Giuseppe, Less than Nation: Central-Eastern European Minorities after WWI (Cambridge: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2013).