3.2.1 Empire and Colonialism in Early Modern History (1500–1800)

© 2023 Kirmse, Rodríguez, and Raben, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0323.28

Introduction

This chapter discusses the meaning of empire and examines the shifting forms of European imperialism and colonialism. Empire as a form of rule had established itself long before 1500. The ancient Greeks and Romans had left legacies that Byzantium and Charlemagne’s Holy Roman Empire were keen to build on and develop. Religious orders such as the Teutonic Knights and commercial configurations such as the Hanseatic League also colonised distant shores.

This chapter aims to explore what changed after 1500. What was different about early modern European empires? However, while tracking their peculiarities, the chapter will also show the diversity of empire, its appeal and abhorrence. To do justice to local complexities, the chapter examines three exemplary clusters: the Russian Empire, the Iberian empires, and north-western Europe.

Commonalities and Differences

The ‘imperial turn’ in history has not only led to greater sensitivity to the lasting importance of empire, but also to a focus beyond conquest, governance, and economic dependence; namely, it has contributed to a broader examination of social and cultural dynamics on the ground.

Still, it remains difficult to generalise about empire. Imperial trajectories were always unique. Often, various forms of domination coexisted in imperial formations. Those living under empire could have vastly divergent experiences, depending on their geographical location, socio-economic position, religion, gender, and more.

However, empires also shared certain commonalities. These included the quest for precious resources, from slave labour to gold and silk. They included the desire to acquire land and control over trade routes, which resulted in large-scale territorial expansion. To legitimise their domination, many imperialists developed feelings of cultural superiority over allegedly primitive ‘natives’. And crucially, prestige, territorial, and economic gains fed into a common European race for the best shares of the spoil.

Analytically, it makes sense to distinguish between different imperial types. Many see the key distinction in basic geography and patterns of conquest and rule, thus differentiating between contiguous landed formations, such as the Habsburg, Ottoman, and Russian empires, and maritime powers with territorial extensions and/or colonial possessions overseas, including the Spanish, Portuguese, and British empires. This does not mean that contiguous empires could not have colonies; it only means that they acquired and viewed these possessions differently.

While maritime empires depended on strong navies, landed empires tended to expand by absorbing neighbouring territories. In both cases local resistance could be fierce, which meant that imperial expansion and rule were often ensured by coercion. Some early modern states, including the Holy Roman Empire under Habsburg rule, engaged in ‘matrimonial imperialism’, that is, the use of marriage bonds between dynasties to bring vast territories under their control, with little military action. Some of Europe’s naval powers also used private companies, such as the Dutch and British East India companies, to pursue commercial interests along distant coasts, acting just as exploitatively as other imperialists but with less concern for state-building and colonisation. The Spanish and Portuguese empires, in turn, replicated the model of European kingdoms and imposed this model on native societies.

While these distinctions may be useful, we must remember that all empires were in constant movement and, at different times, driven by extractive, tributary, territorial, religious, and other concerns. Further, as the British approach in Ireland and America suggests, they could pursue different colonial policies at the same time.

Emerging Empires

Between 1450 and 1550, the Spanish and Portuguese monarchies started building vast overseas empires. Their geographical patterns of expansion were the result of a mixture of foresight, experience, and accident.

While the Portuguese had been exploring the Atlantic for longer, the Spanish moved across the ocean in the late fifteenth century. Starting from their first Caribbean land falls, they expanded west and south-west to the American mainland, following the trail of the Aztec and Inca empires. In 1494, Spanish and Portuguese representatives agreed in Tordesillas to divide global spheres of influence between them, establishing a meridian in the Atlantic, the area west of which became the sole domain of Spanish exploration, and east—including parts of South America—of the Portuguese. In 1529, the Treaty of Zaragoza extended the principle of imperial interest zones to Asia.

Portuguese crown possessions east of the Cape of Good Hope were known as Estado da India from 1505. These possessions—home to powerful political entities, heavily populated and technologically partly superior to Europe—were built on older commercial networks. Politically, the Portuguese Empire was not homogeneous but adapted to the diversity of its territories and peoples. In the seventeenth century, as it increasingly lost positions in Asia to the Dutch, it transformed into a more territorial empire in Brazil. The Spanish conquest of the Americas, by comparison, spread from the Caribbean. Though the first voyages had mostly mercantile aims, the search for precious metals encouraged the appropriation of American territory. The conquest of the Philippines in 1656, in turn, opened a trans-Pacific trade route linking the Philippines and East Asia with the Viceroyalty of New Spain (in the Americas). Spanish and Portuguese colonial societies operated with a high degree of autonomy. Rather than think of Spain and Portugal as centralised empires, we should see them as multi-kingdom monarchies made up of European and overseas elements, with multiple authorities.

The Spanish conquest of the native empires was partly justified with reference to the ‘civilisation’ of indigenous peoples. After the conquest of Mexico-Tenochtitlan, Hernán Cortés (1485–1546) explained the importance of this expansion in a letter (1520) to Charles V, who had just been crowned Holy Roman Emperor in Aachen:

…The possession of [this country] would authorise your Majesty to assume anew the title of Emperor, which it is no less worthy of conferring than Germany, which, by the grace of God, you already possess.

Later, American silver helped to finance the Spanish struggle against Protestantism, underlining the monarchy’s Catholic nature.

By the eighteenth century, Spain still retained most of its American possessions. Portugal, in turn, following the demise of the Estado da India and the discovery of gold and diamonds in Brazil, began to colonise the interior of the territory. At the same time, the use of terms like ‘empire’ and ‘colonies’ in official documentation reflected the Iberian desire to use the Atlantic to promote Portugal and Spain as first-rate powers.

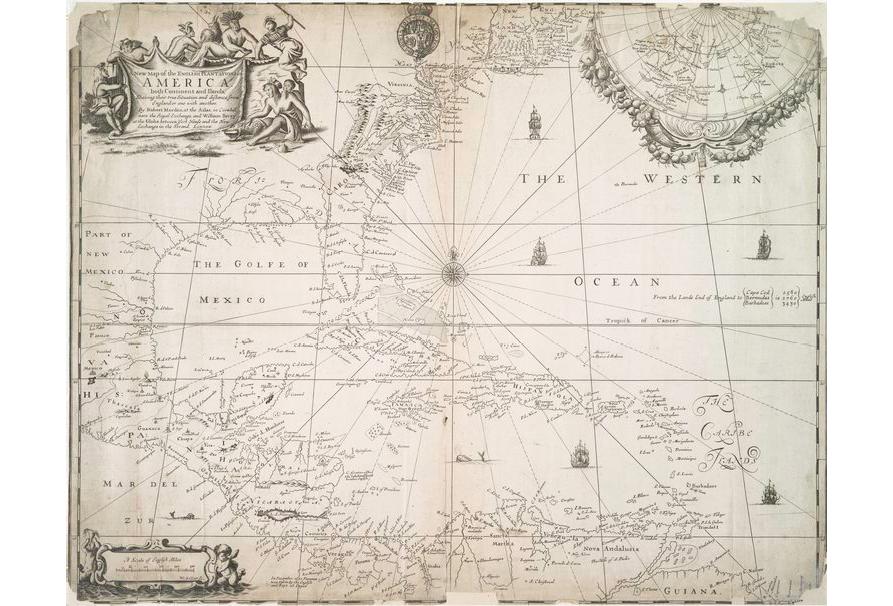

In north-western Europe, coherent attempts to gain a foothold outside Europe started in the late sixteenth century. The English and Dutch are often characterised as ‘merchant empires’, but the term is misleading. The private companies running the colonies operated with strong governmental support. What looked like trading companies in Europe operated as conquerors and colonisers overseas.

In North America, where English settlers established the first permanent colony in Virginia, colonisation only took off in 1607. Remarkably, many leading figures of American colonisation, such as Walter Raleigh, had experience in the English exploitation of Ireland, showing how previous experience influenced early modern imperialism. In the Caribbean and South America, English traders established plantation colonies, attempting to copy the Portuguese and Spanish successes in growing sugar. A third variety emerged along Asian and African coasts, where chartered European companies engaged in the trafficking of humans for colonial plantations and the trade in high-value commodities. Empire thus started out as a string of trading stations and fortifications along the coasts.

Allegedly the first Englishman to refer to empire was the polymath and advisor to Queen Elizabeth I, John Dee (1527-c.1609). However, his call for a ‘British Empire’, only took off in the eighteenth century, a development closely related to the composite nature of Britain after the Treaty of Union (1706). The Dutch, in contrast, in their struggle against Habsburg domination, had developed political theories of Republicanism (and established the Dutch Republic in 1588). These theories also affected their overseas expansion: empires such as that of the ‘popish’ Spaniards were prone to rise and decline, it was claimed; trade profits were the rationale of Dutch overseas expansion. As a result, the Dutch never sat comfortably with the term ‘empire’ (incidentally, nor did the Ottomans, for different reasons, who called their political entity, which they did not deem a colonial empire, the ‘Sublime Ottoman State’).

Although English trade and expansion had a vigorous beginning, their efforts were in many places—with the exception of North America—outpaced by the Dutch. Initially avoiding the Iberian powers, the Dutch grew increasingly bold. From the 1620s to 1650s, they succeeded in pushing the Portuguese to the margins in Asia, firmly establishing themselves in south and south-east Asia. In the Americas, they briefly wrested Brazil from the Portuguese, but after 1650 they retreated, retaining only small footholds in the Caribbean.

In Russia, empire was only formally proclaimed in 1721, after the Tsar’s victory over long-term rival Sweden—a large empire itself at this point—in the protracted Northern War. And yet, despite this late formal proclamation, Russia’s self-image as an empire had emerged centuries prior. After the fall of Constantinople, Russian rulers began to frame the expanding Principality of Moscow as the ‘third Rome’, the defender of (Orthodox) Christendom. Ivan IV (‘the Terrible’) formally adopted the title ‘tsar’—a Russian rendering of the Latin ‘caesar’—in 1547. Since then, grandiose rhetoric framed Moscow as the only legitimate heir to the Roman Empire.

Although Ivan IV wanted access to the Baltic Sea, Russia failed to capture this region until the eighteenth century. It proved more successful in the East. The incorporation of the Muslim khanates of Kazan (1552) and Astrakhan (1556) on the Volga River gave the Tsar an opportunity to show his Christian credentials to the world, represented in stone through the iconic St Basil’s Cathedral on Red Square. More importantly, this huge expansion turned Russia into a truly multiethnic and multireligious entity.

Russian imperialism in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries did not entail overseas colonies, it was more about the advance of its border across the Eurasian landmass. To achieve this, Russian rulers struck deals with neighbouring powers and had new lines of fortification built at regular intervals. They also adopted the techniques of some colonial empires as they started to colonise territories with their own, carefully selected populations while displacing former inhabitants.

By the eighteenth century, colonial expansion was part of Russia’s formal rhetoric. That Russia called itself imperiia from 1721 articulated both an accomplished fact and a growing ambition. It was meant to show Russia’s ‘European’ pedigree to the world. And with Europe as a yardstick, the tsars wanted colonies of their own. The fact that Russian statesmen identified the Ural Mountains as the border between Europe and Asia in the 1730s established the land beyond the mountains as Russia’s own colonial ‘Other’. Fur, the ‘soft gold’ of Siberia, would become the symbol of the empire’s untapped riches, with intellectuals soon hailing the unknown promised land as ‘our Peru’ and ‘our Mexico’.

Fig. 1: Hollar, Wenceslaus, “A new map of the English plantations in America” (1675), The New York Public Library Digital Collections, https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47d9–7ab1-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99.

Between Violence and Pragmatism

While empires often expanded through brutal conquest (in some cases with systematic killings, forced resettlement, and the enslavement of native populations), their subsequent operation was often less dramatic. Once their authority was established, the aggressive rhetoric was usually complemented by pragmatic accommodation. Faced with the reality of cultural, racial, and religious diversity, imperial authorities often set out to institutionalise difference. Whereas modern nation-states usually sought to homogenise their polities and people, early modern empires thrived on difference. In so doing, and while integrating their diverse populations as subjects, they also reinforced hierarchies and—in some cases—segregation. While both contemporaries and today’s academics often frame colonial populations as victims, ‘freedom fighters’, or ‘collaborators’, many locals were none of these things, somewhere in between, or they played different roles at different times. In an economic sense, however, they were heavily exploited. Large parts of the colonial world were turned into a sweatshop for the budding capitalism of Europe. This was perhaps less visible in contiguous empires. While they also extracted resources, the distinction between metropole and colony was often less clear, and inferior social groups such as the peasants were equally exploited.

In many parts of Asia, European powers improvised a bricolage of metropolitan institutions imposed upon local systems of governance: Asian kings, governors, and village heads provided the administrative backbone to enable the Europeans to rule and extract commodities and taxes. In South America, Portuguese and Spanish institutions of government and justice were grafted onto local societies. However, while the Spanish exploited indigenous labour, they depended on the survival of native communities and elites to make the empire work. In the settler societies of less populated (or forcibly emptied) areas, such as South Africa and North America, institutions imported from Europe would dominate because local ones were destroyed or ignored. Landed empires like Russia would employ both approaches at different times: the initial destruction of local institutions in the east and south, where they were considered inferior (before religious tolerance was granted later), and their co-optation in the West—for example, in the Baltic provinces—where local society was viewed as more ‘developed’ than in Russia proper.

Peoples—Peopling

The early modern imperial expansion triggered the movement of people from Europe. Empire provided a job, an escape from home, and the pursuit of honour and wealth. Some went with the aim to return, preferably rich; others left their country for good, not least if they had fled from serfdom, service obligations, or persecution.

The Spanish and Portuguese who went to the Indies were a diverse group. Most came from the lower nobility, others were traders. For the Estado da India, the defence of trade routes shaped the type of migrants: fidalgos (nobles) and officers occupied the key positions to maintain the trade monopolies; most people of Portuguese origin, however, were soldiers, sailors, and convicts. The fidalgos had less interest in Portuguese America, where most colonists were soldiers, convicts, and adventurers (partly attracted by the discovery of gold mines). Numerous missionaries were also among the migrants.

In most of South America and the Caribbean, a small number of administrators ran the slave plantations. The absence of significant political structures in Portuguese America made it easier to justify slavery. While slaves of African origin predominated in north-eastern Brazil, indigenous slaves did most of the manual work elsewhere. Forced labour, however, underpinned colonial ventures across the globe. The exploitative nature of colonialism necessitated coercion.

In Russia, locals were co-opted into positions of borderland authority; in exchange for military service, they were granted land on the frontier. While many privileges were withheld from non-Christians, the borderland populations were gradually integrated into imperial society. After serfdom was formalised for peasants who lived on manorial lands (1649), such peasants were transferred from central provinces to the periphery in large numbers: by the eighteenth century, the lower Volga alone had received half a million migrants. Runaway serfs and convicts, retired soldiers, and religious dissidents joined them on the frontier, which outside towns and forts, remained outside the centre’s reach. Yet, as in the Americas, the frontier was not ‘empty’. Russian rulers displaced borderland communities considered unruly or economically dispensable, including the nomadic Kalmyks and the autonomous Cossacks. The regions forcibly emptied were colonised by Slavic and other European settlers attracted by promises of religious freedom and material benefits.

In Spanish America, the conquest of the native empires, aided by indigenous peoples such as the Tlaxcaltecas, turned most locals into subjects. While they could not be enslaved for this reason, they had to pay tribute and were forcibly Christianised. A differentiated legal regime allowed some pre-Hispanic legal practices to survive and granted indigenous people a degree of autonomy, but it also helped to ensure Spanish domination.

Formal migration was complemented by informal forms of colonisation that reflected the gender imbalance of migratory flows and acted largely outside the law. It led to settlers interacting with local women and producing a mestizo (creolised) society. The crown eventually allowed settlers to bring their wives from Spain, thus reinforcing the Hispanic way of life on the new continent. Passenger records suggest that at least 13,000 Spanish women crossed the Atlantic. Still, intercultural unions grew in number and importance. In Portugal, such unions generated so much concern that the authorities sent Portuguese women, the horfas de rei, to some strategic areas, granting them dowries and helping them to start families that would ensure loyalty to the crown. Nonetheless, this did not stop the formation of a multicultural society over time. The same was true along Asian and African coasts, where large communities of creolised people emerged, along with status hierarchies based on perceptions of race. Such hierarchies characterised virtually all colonial empires, though the degree of official racism varied and religious conversion could mitigate exclusionary policies. Still, on some imperial peripheries (including the Eurasian frontier), intermarriage was the exception, rather than the rule.

In general, the British and Dutch were less keen to ‘colonise’ their territorial acquisitions, in the sense of sending European settlers, than Russia and the Iberian powers. British expansion to North America was an exception: the colonists disembarking in Virginia were the first of more than 350,000 immigrants from the British Isles peopling what became known as the Thirteen Colonies. Africa and Asia drew much smaller numbers of settlers because of the climate, the limited size of most possessions, and because the chartered companies did not allow free settlers. Still, Dutch activity in Asia was not matched by other European powers until the mid-eighteenth century. In the course of almost two centuries, about one million people travelled on Dutch East India Company (VOC) ships to South Africa and Asia. Most of them were from other European countries, especially the German lands.

Conclusion

Early modern empires, for all their diversity and dynamism, differed from their predecessors in several respects. The discovery of the New World and improvements in technology and navigation gave them the possibility of global reach. The compression of time and space emboldened Europeans, stirred up their rivalries, and opened up new possibilities for enrichment.

The late eighteenth century saw some major changes, with the independence of the Thirteen Colonies (1783) and Haiti (1804), followed by most of Spanish America and Brazil by 1824. At the other end of the globe, Dutch power in Asia declined while, from the mid-eighteenth century, the British in India evolved from a mercantile presence into a more dominant, tax-extracting coloniser. The Dutch made this change more reluctantly, continuing to stress the commercial nature of their business.

In Russia, many traits of imperial rule persisted: geographic expansion was accompanied by ever more diversity, the co-optation of locals, elusive rule, but also violent crackdowns. The proclamation of empire, however, did herald a new era, and unlike the Dutch, the Russians were eager and proud to wield the imperial title.

Discussion questions

- Not all European societies were equally involved in empire-building and colonialism. What were the most important commonalities and differences?

- What were the consequences of empire-building and colonialism for early-modern Europeans?

- Do these historical processes still shape Europe today?

Suggested reading

Burbank, Jane and Frederick Cooper, Empires in World History: Power and the Politics of Difference (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2011).

Disney, A. R., A History of Portugal and the Portuguese Empire, Vol. I: From Beginnings to 1807 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012).

Elliot, J. H., Empires of the Atlantic World: Britain and Spain in America 1492–1830 (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2006).

Parker, Charles, Global Interactions in the Early Modern Age, 1400–1800 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010).

Restall, Matthew and Kris Lane, Latin America in Colonial Times (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011).

Restall, Matthew, Seven Myths of the Spanish Conquest (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004).

Romaniello, Matthew, The Elusive Empire: Kazan and the Creation of Russia (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 2012).