3.2.3 Empires and Colonialism in Contemporary History (1900–2000)

© 2023 Surun, Pešta, and Metzler, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0323.30

Introduction

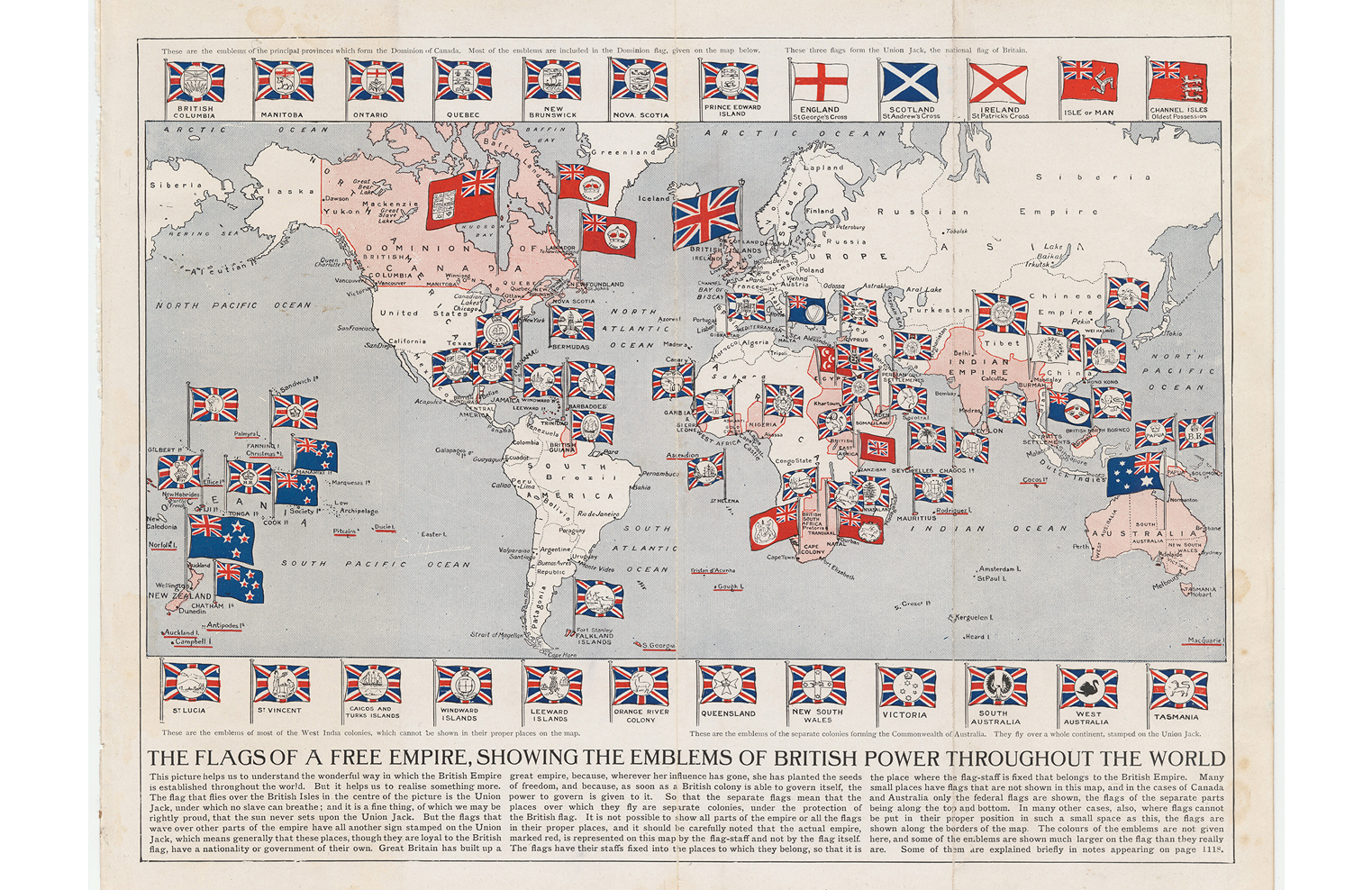

At the beginning of the twentieth century, the world was marked by unprecedented European dominance. It was the Age of Empires, a period of high imperialism which began in the 1870s. Through the following decades, European powers (joined by Japan and the United States), justified by notions of a civilising mission, conquered most of the globe. In 1914, there were not many countries and territories across the world, except for Latin America, which were not subject to one of the existing empires.

Fig. 1: Arthur Mees, The Flags of a Free Empire, Showing the Emblems of British Empire Throughout the World (1910), Public Domain, Wikimedia, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Arthur_Mees_Flags_of_A_Free_Empire_1910_Cornell_CUL_PJM_1167_01.jpg.

However, by the end of the twentieth century, there were only a few remnants of these once-global empires. The steady decline of colonial power and its ultimate disintegration is perhaps one of the most significant trends in the global history of the twentieth century. Yet, even with the decline of direct colonial rule, there are still many imperial remnants around the world that, to this day, influence the development and internal affairs of post-colonial countries.

Contiguous Empires in Eastern Europe

While colonialism is often considered a phenomenon associated with Western Europe, the peoples of Central and Eastern Europe had their own experience with empires too. Until 1918, most territories of Central Eastern Europe were a part of one of four empires: German, Austro-Hungarian, Russian, and Ottoman.

Despite the demise of those empires after the Great War, imperial dreams remained. Germany and Hungary set themselves on a path of revisionism, seeking to reclaim their lost territories, and briefly reinstituting their rule during the Second World War. In particular, Germany under Nazi rule had an ambitious imperial vision of vast East European spaces subjugated to and colonised by German settlers. Soviet Russia also sought the lands it had lost to newly emerging countries after the First World War and tried to retake them in 1939 and then again, successfully, in 1944–1945. But even the new countries, built in 1918 on an anti-imperial narrative, were not entirely immune to imperial temptations. There were voices in both Czechoslovakia and Poland that asked for certain former German colonies, the possession of which was supposed to secure to those countries a place among the Western European powers. Moreover, policies which dealt with minority populations and peripheral territories in the new countries were often not so different from those of the old empires, sometimes creating the impression that the empires did not leave but were only reconfigured. The Balkan Peninsula became a fault zone for several imperial visions. Almost every country in the region followed the path of border revisionism and sought to enlarge its territory. During the 1930s, most of the Balkan Peninsula also turned to different forms of dictatorship, which were more willing to use force to fulfil their ambitions.

In the post-war era, the socialist countries led by the Soviet Union officially denounced colonialism, and support for the anti-colonial national liberation movements became a crucial part of socialist ideology and practice. The dichotomies of the Cold War turned anti-colonialism into a powerful weapon in international relations, which the socialist countries used against the (former) colonial powers. Drawing parallels between imperialism and fascism and supporting the emerging ‘Third World’ economically and politically, they tried to use the momentum of decolonisation to get an upper hand in the global conflict.

Nevertheless, the USSR could be also viewed as an empire sui generis, even though it does not fit with the classic understanding of the concept of colonialism, associated mostly with the Western European overseas empires. The USSR inherited most of the territories from tsarist Russia and, despite its rhetoric and its nominally federal structure, it remained very centralised, with all power in the hands of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union. The peripheral Soviet territories, such as Central Asia, remained underdeveloped long after the Cold War was over. Even Soviet allies in Eastern Europe were only semi-sovereign; when one of them deviated from the set sphere of action, a Soviet intervention usually followed to put it back on track. This was the case in the German Democratic Republic in 1953, Hungary in 1956, and Czechoslovakia in 1968. Even after 1991 in post-Soviet Russia, we can find elements of imperialist thought, embodied in the interventions in what is considered to be a Russian sphere of influence, such as Moldova (1992), Georgia (2008), or Ukraine (2014).

Post-1989 Central-Eastern European societies regarded (and still regard) colonialism as a foreign, Western European problem, which did (and does) not concern them. Debates about colonial legacies are usually pervaded by the argument that Central-Eastern Europe did not possess any colonies, and should therefore not be punished, shamed, or forced to apologise for Western colonialism—largely neglecting the wider circumstances and interconnectedness of early-modern and modern-era trade.

Theories and Practices of Colonial Government

During the 1930s, a dispute emerged between British and French colonial policymakers about the putative superiority of their respective models of colonial administration. On the British side, the model of Indirect Rule, theorised by the British colonial administrator Lord Frederick Lugard (1858–1945) in The Dual Mandate in British Tropical Africa (1922), was characterised by recognition of native authorities and respect for local customs: under this system, British administrators would simply supervise indigenous chiefs and ‘educate’ them in the art of good government. In contrast, the French colonial doctrine was seen as assimilationist and centralising.

A purely direct rule was in fact impossible, partly because the empires did not have the means to deploy a large administrative staff in their colonies, and partly because they would not have had the legitimacy to administer hostile populations. In fact, colonial domination could not have been possible without the participation of a segment of the colonised populations. In some territories, the colonisers had recourse to traditional indigenous elites (Indian Princes, Rajahs and Maharajas, Javanese bupatis or priyayis, African chiefs and kings) with varying degrees of autonomy to collect taxes, requisition men for forced labour, and maintain social peace. In others, they enlisted intermediaries (‘educated natives’, ‘évolués’, ‘assimilados’) to perform subaltern functions in the colonial administration (interpreters, secretaries, guards).

However, colonial rule was coercive in many ways and for various reasons. Firstly, the agents of the colonial authority concentrated all kind of powers (legislative, executive, judicial and financial) and enjoyed a certain autonomy from the imperial governments because of the remoteness of the metropolis. This led to widespread abuse of power and outbursts of violence, such as the Congo scandals (under both the French and the direct rule of Belgian King Leopold II) caused by forced, labour-intensive requisitions at the time of the rubber boom in the early twentieth century. Secondly, the systemic violence of the colonial policing can be explained by the populations’ absence of consent to the colonial order: some historians consider it a symptom of a weak state. Third, the extraction of revenue and men through the levying of taxes, crops, labour, or conscripts was a primary function of colonial rule, which could not be implemented without coercion. Colonial administrators found racialist or paternalistic justifications for it in colonial ideology: it was a matter of ‘putting to work’ indolent populations who were, in their view, incapable of extracting resources from their land beyond the satisfaction of their vital needs. And when part of these functions was entrusted to indigenous elites, the consequent violence was no less harsh. Finally, colonial administrations put in place exceptional legislation that ensured both the maintenance of colonial order and the proper functioning of the extractive policies: the status of indigene or colonial subject was both that of a subaltern in a system of social and racial domination, and a legal status that subjected the individual to rules and punishments particular to the colony.

The so-called ‘civilising mission’, a well-known element of colonial ideology, generated paradoxical effects. Indeed, its effective application would have rendered the maintenance of domination irrelevant and futureless, since the Europeans could no longer invoke their alleged superiority. The means put into education were therefore very limited: in Algeria, only 4.5 percent of Muslim children were enrolled in school in 1907, and in India, one in 100 inhabitants spoke English in the 1920s. Secondary education was limited to a handful of individuals, and scholarships to study at university, usually in the imperial capitals, were issued sparingly. Officials feared that they were producing ‘uprooted’ individuals who would no longer have a place in their native society and would believe themselves to be the equals of Europeans. In fact, the newly educated elites saw their aspirations disappointed and their social ascent limited by the ‘colour bar’. Unsurprisingly, they played an important role in socio-cultural and political transformations: most of the nationalist leaders of the independence era were part of this category. They had turned against the colonisers the weapons they had received through education.

It was only when the empires were threatened that they seemed to take the injunctions of the civilising mission seriously: the schooling of Muslim children in Algeria rose from fifteen percent to thirty percent during the 1950s. Major development projects involving investment in the colonies were launched: the Colonial Development and Welfare Act in the British Empire (1940), the Investment Fund for Economic and Social Development (1946) in the French Empire, or the ten-year plan for the economic and social development of the Belgian Congo (1949). Late colonialism could therefore be referred to as ‘development colonialism’.

Decolonisation of Western Empires

After a first wave of decolonisation in the Americas during the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, the dissolution of European empires continued after the First World War. Outside of Europe, the dependent territories of the vanquished empires did not gain independence; they were only reorganised as League of Nations mandates under one of the victorious powers—either the United Kingdom or France. However, the Wilsonian concept of self-determination, which had proved useful in weakening Germany and the Austro-Hungarian empire, began to backfire in the form of rising demands for independence from the colonies. Even though some of the political bodies for national liberation predate the Great War (such as the Indian National Congress founded in 1886), the struggle for independence can be traced mostly to the interwar period. Inspired by Wilsonian or Leninist or other ideas, the generation of Europe-educated leaders began to fight for national liberation. The fight for national liberation took on global scope: in this era, international organisations such as the League against Imperialism, which sought to foster global anticolonial solidarity, emerged. The times had changed and high imperialism became less and less acceptable in the international community; when the Italians invaded Ethiopia in 1895, it was not contested, as it was not unusual in that time. But when they tried again forty years later, it caused an international crisis.

It was not until after the Second World War, however, that the dynamics of decolonisation could no longer be contained by the European powers. As a result of the Japanese occupations, national movements had strengthened in Southeast Asia during the war. In India, too, British rule had lost legitimacy over the course of the conflict. While the Netherlands and France struggled in vain for several years to retake their colonies in the Dutch East Indies (Indonesia) and Indochina, the British withdrew from India in 1947. Due to inadequate preparations for independence, the British not only caused a humanitarian catastrophe as a result of the partition of India and Pakistan, but also left behind a territorial conflict in Kashmir which is still contested today.

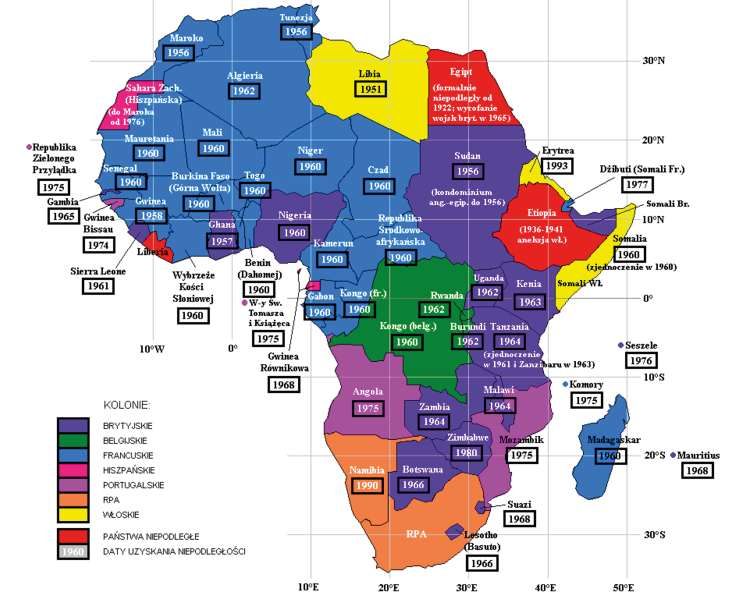

Fig. 2: “Decolonization of Africa”, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Decolonization_of_Africa_PL.PNG. This map shows the years in which African countries finally took back their independence from European colonisers. Most notable is the year 1960 (the Year of Africa), in which eighteen African nations declared their independence.

While most of Asia had become independent by the mid-1950s, it took another two decades before independent autonomous states replaced the European colonial empires in Africa as well. The wave of decolonisation in Africa reached its peak in 1960, the ‘Year of Africa’, which alone saw the emergence of eighteen new states on the continent. As in Indochina and Indonesia before it, Africa’s path to independence was often fraught with bloody military conflicts, humanitarian problems, and flagrant human rights violations—a development that was clearly at odds with the pacification of the European continent itself, which was taking place under the auspices of Western European integration. In Africa, ‘Year of Africa’ enthusiasm was abruptly ended when the former Belgian colony of the Congo, a huge territory with one of bloodiest and most tragic colonial histories, fell into chaos and civil war mere weeks after the proclamation of independence. The decolonisation of Angola, Mozambique, Spanish Sahara, Portuguese Guinea and São Tomé and Príncipe in the mid-1970s marked the final dissolution of European political rule in Africa. Anti-colonial struggle of a similar kind, however, continued in South Africa and Zimbabwe; while they were independent since 1961 and 1965, respectively, they were ruled by the white settler minority, which was seen as a continuation of the old, colonial arrangement.

Post-colonial Legacies

However, this by no means meant that European influence in the Global South disappeared altogether. At the instigation of France in particular, the early institutions of European integration relied on association with African states, which perpetuated asymmetrical economic relations from the colonial era. Only slowly (and by no means completely) were African societies able to free themselves from this subordination. Moreover, only in a few cases has it been possible to establish stable, democratic, and constitutional orders after decades of foreign rule. The extent to which this is a consequence of colonialism or local conflict structures is disputed in historical and social science research.

European societies also changed as a result of decolonisation. Great Britain and France experienced significant immigration from their former colonies: in the British case mainly from Asia and the Caribbean, and in the French case mainly from North Africa. The integration of migrants was far from a universal success. They often found themselves in difficult social and economic circumstances. While settlers from Algeria, who were read as ‘white’, quickly gained a foothold in French society, North African Muslims remained marginalised. In many cases, their descendants live in the social hot spots of the banlieues and have little chance of upward mobility. In Britain, the rights of nationals of the Empire or Commonwealth have been considerably restricted over the decades, up to and including the threatened expulsion of members of the so-called ‘Windrush generation’ who themselves or whose parents had arrived in the country in 1948. The integration of post-colonial migrants was most successful in Portugal, where many were able to find jobs within a short time.

This had to do with the regime change in Portugal in 1974. The ‘Carnation Revolution’ put an end to the right-wing authoritarian regime that had existed since 1933. The experience of the wars waged by the regime in Africa, which were as brutal as they were unsuccessful, contributed directly to the growth of Portuguese opposition and military resistance to the government. In France as well, a fundamental change occurred as a result of decolonisation crises, when in 1958 the Fourth Republic, weakened by defeat in the Indochina War and the ongoing Algerian War, collapsed. It was replaced by the Fifth Republic under the leadership of Charles de Gaulle who, however, needed until 1962 to consolidate his presidency against domestic crises and the threat of an impending military coup.

Western European societies long refused to face up to their colonial past, including the legacies of conflict-ridden decolonisation. The dissolution of the empires was followed by a long phase of amnesia and deliberate neglect of colonial crimes and human rights violations. Only since the 2000s has a more conscious reappraisal, which is far from being completed, begun. It includes questions of memory culture and political-historical education as well as the eminently political demands of the formerly colonised for the restitution of artifacts, works of art, and human remains as well as for reparations.

Neo-colonialism and Remnants of the Empires

Europe’s influence on its former colonies did not cease to exist with their formal independence. In many areas, the former ‘mother’ country kept a strong position and close business relations with the new states. France maintained strong ties with its former empire, whether in trade, military, or cultural relations (Francophonie). In 1958, Guinea tried to sever those ties and was punished by President de Gaulle for it; the country was boycotted and the staff of colonial administration sabotaged what it could before it left. France also holds a record in the number of military interventions and covert coups (often using mercenaries) in Sub-Saharan Africa.

More subtle ways of exercising influence over the post-colonial states were also employed. The Central African and West African CFA franc that has been pegged to the French franc—and later the Euro—is perhaps the most blatant example of the structural impact a European country can have on its former colonies’ trade and monetary policies. Since the 1980s, many post-colonial countries became heavily indebted to the International Monetary Fund or the World Bank; the money, however, came with obligations of ‘structural adjustments’. The institutions, to a large extent under the control of Europe and North America, thus created new, neo-colonial tools enabling the North to maintain the upper hand over the South.

Even though most colonial holdings have been abandoned over the course of the twentieth century, there are still remnants of the empires, such as the Canary Islands and Madeira in Africa, several British, French, and Dutch territories in the Caribbean, British and French islands in the Indian and Pacific oceans, and even Danish dominion over Greenland. Some of these territories were fully incorporated within European state structures, some received different levels of autonomy. In most cases, there is consensus about remaining subject to European administration.

European Third-Worldism

Most of the first generation of anti-colonial leaders were educated in Europe. There, they also adopted the notions of a European nation-state and other concepts, used for building the post-colonial countries, and sometimes they were criticised by later generations of post-independence leaders. However, transfers of knowledge and cultural patterns flowed both ways. Since the late 1950s, the Western European left increasingly looked for inspiration in places other than the Soviet Union, gradually turning to the ‘Third World’. It was intellectuals like Frantz Fanon, a Martinican psychiatrist who demanded the dismantling of colonial empires even at the cost of violence, who left a strong impact on the European left. ‘Third-Worldism’ became a cornerstone of the New Left and protest movements that peaked in the late-1960s. From Algeria, the focus turned to Angola and Mozambique, to the apartheid regime in South Africa, and most of all, to Vietnam. Solidarity campaigns and protests against the US war in Indochina were perhaps the most visible feature of the student movement. In the ‘Third Worldist’ perspective, the European proletariat was no longer the class that was supposed to lead the revolution, as it had become too comfortable in the system. The new hopes were placed in the rural population of the Global South, the “damned of the Earth” (Frantz Fanon). The theories of Mao Zedong, Che Guevara, or Régis Debray were attractive, because they presented not only an alternative to capitalism, but also to the Soviet bureaucratic socialism, which was seen as discredited—particularly after the interventions in Hungary and Czechoslovakia.

Conclusion

Decolonisation is one of the most significant global processes of the twentieth century. Different kinds of rule in colonial territories gave rise to different kinds of decolonisation. While formal independence has been achieved in most parts of the world, there are still many remnants and long-term ramifications of colonialism. We can still see efforts to maintain asymmetric ‘special relationships’ between former colonial powers and their former colonies. The consequences of colonialism can be observed in international migration and formation of transnational identities. The emancipation process in the ‘Third World’ also affected conceptualisations of a global revolution among European leftists.

Discussion questions

- What were the main features of colonial rule?

- What was the impact of the rise of the Soviet Union on European imperialism?

- How successful was decolonisation?

- In which ways do European empires still shape our world?

- Is the EU a colonial power?

Suggested reading

Burbank, Jane and Frederick Cooper, Empires in World History: Power and the Politics of Difference (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2010).

Buettner, Elizabeth, Europe after Empire: Decolonization, Society, and Culture (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2016).

Hansen, Peo and Stefan Jonsson, Eurafrica: The Untold Story of European Integration and Colonialism (London: Bloomsbury, 2014).

Holland, Robert, ed., Emergencies and Disorder in the European Empires after 1945 (London and New York: Routledge, 1994).

Jansen, Jan. C. and Jürgen Osterhammel, Decolonization: A Short History (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2017).

Rodney, Walter, How Europe Underdeveloped Africa (London: Bogle-L’Ouverture Publications, 1972).

Thomas, Martin and Andrew S. Thompson, eds, The Oxford Handbook of the Ends of Empire (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018).