4.2.3 Social Engineering and Welfare in Contemporary History (ca. 1900–2000)

© 2023 Barillé, Moses, Plets, and Sonkoly, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0323.45

Introduction

The twentieth century witnessed a number of significant external pressures on populations across Europe, from two World Wars and an economic crash between them, to the Cold War, the crumbling of colonial empires, and the fall of the Iron Curtain. Against this backdrop, there were major reconfigurations of the urban landscape and the experiences of work, social class, and gender relations. Meanwhile, new research, alongside increasing academic and professional specialisation, contributed to greater knowledge about social problems and generated innovative policy ideas to tackle them. These transformations intersected with broader trends in thinking about the role of the state in an era that many saw as ‘modern’. What were the problems of ‘modernity’, and would they require new social policies? Would they require the creation of what came to be known—sometimes derisively—as ‘the welfare state’? To what extent were these interventions attempts at ‘social engineering’?

The tone and extent of state-driven interventions in the social sphere—interventions in the workplace, in the family and reproduction, and in individuals’ health and wellbeing—increased greatly over the twentieth century. In part, the increase in activity stemmed from the rise of new political ideologies and concomitant social and political experiments under fascism, National Socialism, communism, and liberal social democracy, each of which sought to carve out its own ideal of ‘modern life’. Yet it was also the growing capacity of European states to intervene, as well as increasing information and expertise, that may have proved most significant for this transformation. We explore three aspects of social politics in twentieth-century Europe in this chapter—urbanisation and urban planning, work and social class, and the family and reproduction—before reflecting on the broader transformation of social welfare systems during this period.

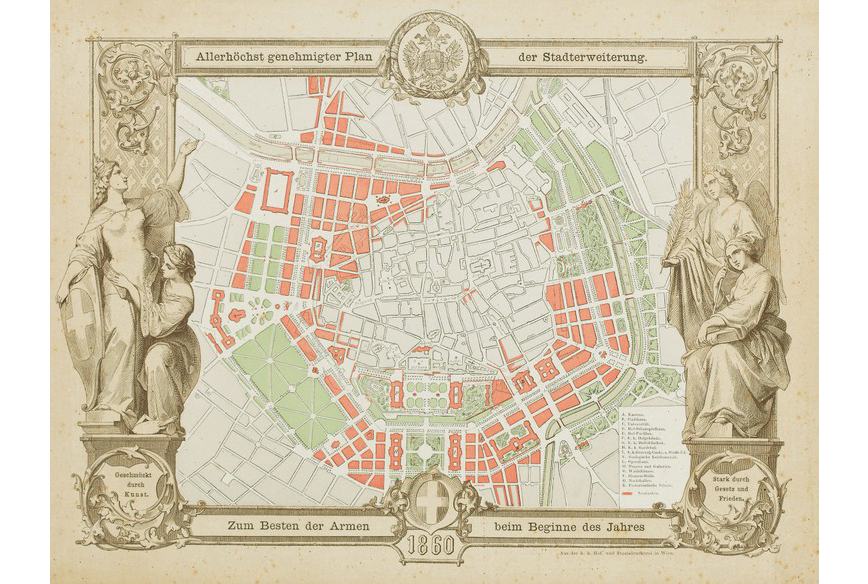

Fig. 1: K.K. Hof- und Staatsdruckerei in Wien, “Plan Stadterweiterung Wien 1860” (”City expansion plan for Vienna in 1860”), Public Domain, Wikimedia Commons, https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Datei:Plan_Stadterweiterung_Wien_1860.jpg. A plan for the expansion of Vienna’s city centre, including the famous Ringstrasse (Ring Street). It was meant to connect the city’s centre to the bourgeoisie of the growing Viennese suburbs, and also to promote the city centre as a hub for shopping and culture.

Urbanisation and Urban Planning

During the twentieth century, the urban population of Europe quadrupled, attaining 450 million inhabitants. Europe became a predominantly urban continent, in which three out of four people lived in cities and towns. Contrary to the previous century, however, this impressive progress was not the result of steady, unbroken growth. European urbanisation and the urban planning associated with it can be divided into two major periods, separated by the 1970s. The first period is characterised by intense industrialisation inherited from the nineteenth century, and it was only temporarily halted by the two devastating World Wars and the economic crisis of the 1930s. This is the period of the institutionalisation of urban planning as a discipline and as a set of successive theories to solve the problems of the urban societies of the industrial age.

The second period is the emergence of the post-industrial city, which is marked by urban deindustrialisation, by the rise of the service economy, by increased connectivity in travel, migration, and mass tourism, as well as by the intensification of the inter-regional disparities and continental unification characterised by the decommunisation of Central and Eastern Europe starting in the last decade of the twentieth century.

In fin-de-siècle urban Europe, rising social tensions required professional solutions, which led to the institutionalisation of urban planning as an academic concern, with the first course on it offered at the University of Liverpool in 1909. The successive paradigms of this discipline were marked by two major characteristics: (1) they took it for granted that the proper urban design determined by a suitable ideology generated a principled urban society free from the social evil of uncontrolled capitalism; (2) urban planning as a discipline was often playing catch-up, as its new schemes for reformed urban life were constantly being superseded or pre-empted by unexpected factors, like rapidly changing technologies and fast-evolving social conditions. Consequently, these unexpected or unconsidered factors (such as automobiles, individualisation, commercialisation, the growing significance of leisure time, deindustrialisation, etc.) could lead to the discreditation and the replacement of the precedent paradigms and to the reconstruction or degeneration of the urban landscape created by them.

The most significant movements of the first period of urban planning were:

- ‘Garden Cities’, which offered an alternative at the turn of the twentieth century to overcrowded, immoral, and industrial neighbourhoods by proposing resettlement in remote greenbelts, but later criticised as the predecessor of suburbanisation models and dormitory cities;

- ‘City Beautiful’, which was the twentieth-century North American reception of nineteenth-century European urban interventions with the purpose of grandiose political representation (such as the reconstruction of Paris by Georges-Eugène Haussmann (1809–1891) and the construction of the Viennese Ringstrasse), which returned to Europe in the 1930s, when totalitarian regimes applied its models to rebuild their capitals (such as Nazi Berlin or Stalinist Moscow) in order to impose their megalomaniac visions;

- ‘Zoning’ and modernist urban planning, a category of various movements united by their quest to establish an enduring equilibrium between various urban areas determined by their specific activities (such as production, services, residence, recreation, etc.), but later criticised for having amplified unhealthy and individualistic car transport, for segregating urban neighbourhoods from each other, for establishing soulless ‘new towns’, and for causing urban blight in city centres.

The successive failures of these planning paradigms, accompanied by the effects of economic crisis, and the growing democratisation and identity movements in the 1970s, led to the (1) deurbanisation of many industrial cities; (2) the dwindling economic role of central power in an increasingly neoliberal urban planning; (3) the subsequent reurbanisation of urban centres and cities and towns, which were disfavoured by enforced zoning and industrialisation; (4) growing awareness among urban citizens of the distinctive identity of their neighbourhood, which was legally recognised as participative urban design in several Western European countries; (5) the gentrification of formerly abandoned urban areas causing social and cultural tensions between the old and the new inhabitants.

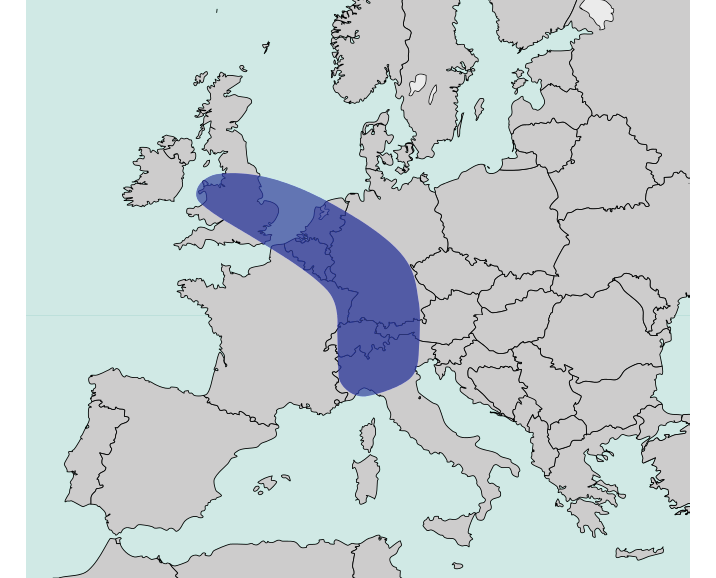

Fig. 2: Arnold Platon, “Blue Banana”(21 February 2012), CC BY SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Blue_Banana.svg. This strip of urban centres in western Europe, drawn around the six focal cities specified above, outlines one of the most rapidly developing regions of the twentieth century. In the mid-twentieth century, the ‘Blue Banana’ contained one of the world’s highest concentrations in people, money, and industry.

The corresponding reinterpretation of the European city followed in the 1980s, when a transnational urban axis of cities was recognised in Western Europe. These cities were successfully emerging from the deindustrialisation process thanks to their combination of advanced manufacturing and tertiary occupations. This axis—designated the ‘Blue Banana’, and stretching from Manchester to Milan, including London and Paris as pre-eminent centres—could be interpreted in two ways. It could be seen either as the new, innovative hub of Europe replacing the former significance of industrial regions or, conversely, as the return of a long-lasting urban network obstructed by the rise of nation-states and national urban systems since the nineteenth century.

The late twentieth century European city was furnished with a post-industrial (or post-modern) urban planning, which was simultaneously more receptive to local needs and more vulnerable to private or corporate economic interests, with the new ideal of the sustainable city harmoniously integrating urban culture, urban economy, urban society and urban environment as inducements for innovation.

Labour and Class Struggles

The twentieth century saw overall improvements in working conditions for all categories of workers. Nevertheless, economic crises, war, and globalisation had lasting consequences for the ways in which people viewed their relationship with work.

In most European countries, liberalism came under serious criticism in the early years of the century. Between 1906 and 1914, the British Liberal Party converted to the idea of social intervention by the state, in response to pressure from the trade unions. It was therefore not surprising that the Old Age Pension Act was passed in 1908, granting a retirement pension to the most destitute over the age of seventy, without prior contribution. The National Insurance Act in 1911 covered sickness and unemployment. In France, the logic of assistance prevailed with a series of laws that brought relief to the poorest wage earners: the law on free medical assistance (1893), the social protection of the elderly and the infirm (1904), or aid granted to large families with four or more children (1913). The German model of a compulsory health and old-age insurance system was adopted by several countries such as Austria in 1888, Denmark in 1891–1892, Belgium in 1894 and Luxembourg in 1901.

State intervention became widespread during the First World War, and the unions were involved in industrial and labour policy. However, no ambitious measures were taken when peace was restored. In April 1919 in France, the vote on the eight-hour day and the recognition of collective agreements did mark a step forward, but its scope was limited by many derogations. In Great Britain, the law of 1920 expanded old-age benefit, and unemployment insurance, which was initially introduced in large industries, was extended to workers in all sectors of industry. In Germany, social policy was one of the foundations of an otherwise very fragile Weimar regime: the Bismarckian legacy was perfected, particularly in the fight against unemployment, which was on an unprecedented scale since post-war demobilisation.

The crisis that hit all European countries from 1929 onwards weakened the social policies already implemented. In Germany, the serious effects of the crisis (unemployment, galloping inflation) led to a reduction in social spending: unemployment insurance was denounced as an aggravating factor in the crisis. The system was partially saved by the state in 1930–1931, with a severe reduction in benefits. In Great Britain, too, the crisis weakened the system of assistance to the unemployed and cuts were made to the aid granted. Finally, in France, despite important measures aimed at promoting social progress, the Popular Front hardly modified France’s social protection policy, which remained limited to the social insurance laws of 1928 and 1930.

Government action and state intervention in economic life played a decisive role during the period of reconstruction, and an accompanying role in growth during the so-called ‘Trente Glorieuses’, the prosperous three post-war decades from 1945 to 1975. Until the early 1970s, most economic policies were inspired by John Maynard Keynes (1883–1946) and aimed at regulating the pace of growth. In some countries, the statist tradition and the influence of socialist ideas and organisations meant that interventionism was taken further: in France, numerous nationalisations were carried out between 1944 and 1946, and similar action was taken in Great Britain after the 1945 Labour election victory. The other aspect of this coordinating state policy was planning, and again it was France which, led by Jean Monnet, was one of the states which went furthest in this field.

Governments also intervened more and more in the social sphere: in relations between employers and employees, setting minimum wages and working conditions (duration, paid holidays, etc.); by developing education and pension schemes; or by setting up—and this was the great innovation of the post-war period—social protection systems aimed at ensuring a minimum level of security for all. Thus, in the aftermath of the war, the field of the welfare state expanded, the philosophy of which consisted no longer in basing ‘social security’ on the traditional concept of the employment contract and insurance (which guaranteed certain elements of the population against a limited number of risks), but instead basing it on the principle of national solidarity: the community of the nation should ensure well-being for all.

Family and Reproduction

Concerns about transformations associated with ‘modern life’ lay at the heart of widespread debates and new policies on the family and reproduction over the course of the century.

The dawn of the twentieth century was marked by anxieties about declining fertility and the health of babies and children. As a consequence, efforts to improve the birth rate as well as the health of infants and children took off in many European countries in the years leading up to the First World War. These discussions were shaped by war, driven by concerns about past defeats and potential future defeats. In France, these debates originated in the aftermath of an embarrassing loss in the Franco-Prussian War in 1870–1871, while in Britain, they were influenced by dissatisfaction with British performance in the Boer War in South Africa in 1902. Meanwhile, observers during this period took increasing notice of high and (in some places) rising infant mortality rates. For example, the last quarter of the nineteenth century in Britain saw a decline in the adult death rate but an increase in infant deaths. These considerations contributed to new questions about how to engineer society through reproduction and the family—and one answer to that question was eugenics.

Against a backdrop of centuries of continental European warfare and increasing military skirmishes in imperial outposts, alongside worrying statistics about stagnant or even growing infant mortality rates, policy proposals for infant milk dispensaries (to combat potential illness from exposure to unsanitary or insufficient food and water for babies) and family allowances gained support across the political spectrum. Encouraging and protecting the family became an issue for both right-wing nationalists, keen to pursue national glory through a high birth rate and healthy military recruits, and also feminists who sought to assist mothers and their children. This trend could be seen, for example, in the work of feminists like Eleanor Rathbone in the United Kingdom, who campaigned for family allowances for over twenty years until they were ultimately introduced in 1945. They could also be seen in initiatives like France’s Médaille de la Famille française, Adolf Hitler’s Mother’s Cross programme (1938), and the Soviet Order of Maternal Glory (1944), which were introduced to encourage women to have more children. These initiatives were all based to a certain extent in eugenics—the children of these families needed not only to be plentiful but also to be raised well.

After the Second World War, the language and some of the policies related to the family and reproduction were necessarily restrained by a backlash against the kind of eugenics associated with Nazi Germany. However, state-run policies on the family and reproduction continued to play a large role and were even expanded. Post-war concerns about ‘problem families’ and troubled youths meant that, in Great Britain, social work and interventions into a growing number of single mother households became more widespread. Meanwhile, growing numbers of women in the workforce both during the war and in the decades afterward led to an expansion of publicly funded education and childcare as well as the expansion of maternity (and, later, parental) leave. Across the Communist bloc, the increase in public early years provision was especially marked. For example, in the German Democratic Republic, women were expected to return to work soon after their children were born, and high-quality nurseries were set up to take care of their infants. Across much of Western Europe, by contrast, women in the middle decades of the twentieth century were expected to stay at home—or for those who had worked during the war effort, to return home—to care for their young families, and they were encouraged to do so with various forms of child benefit.

Debates about fertility rates, as well as child benefit and childcare, continued to shape European welfare politics well into the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries. These discussions were partly shaped by the mass introduction of the birth control pill after 1960, which meant that women and couples could shape their own reproductive lives more than ever before. However, the birth rate was now not as much a reflection of worries about nationalism and militarism—although, of course, these nationalist anxieties never diminished entirely from view, especially as new waves of post-war migration from former European colonies and beyond (such as ‘guest workers’ from Turkey) precipitated anxieties about increasing numbers of ‘non-white’ populations or interracial children. Instead, the declining birth rate in countries such as West Germany and Italy was primarily a concern because the large social security systems that had been erected after the Second World War relied on new, young workers to contribute part of their salary to keep them going. At the same time, demands for access to affordable, high-quality childcare grew in the decades after 1968 along with the associated rise of Second Wave Feminism, which saw an increase in women not only working but seeking long-term careers and well-paid jobs.

Thus, over the course of the twentieth century and into the twenty-first, expectations that social policy and the state more generally were necessary and useful supports for the family grew. Nonetheless, the relationship between the state and the family was always complex, sometimes morally challenging, and often fraught.

Welfare Systems in and as Government—East and West—in the Twentieth Century

During the twentieth century, grassroots socio-political activism, changing ideals, and a changing political landscape culminated throughout large parts of Europe in the institutionalisation of various types of welfare systems. In the West, the aftermath of the Second World War is often associated with the birth of the modern welfare state. Although states and governments in previous centuries also set up initiatives and instruments to ensure the welfare of its subjects, from the mid-twentieth century more comprehensive systems were put into place that shaped almost every aspect of human life. Another strong difference with previous periods was the strong institutionalisation and development of elaborate bureaucracies. This aggressive involvement of the state in poverty reduction, education, housing, and healthcare should be seen as a response to the economic depression of the 1930s and the deep social problems caused by laissez-faire capitalism.

There was also a political dimension to the introduction of the welfare state in Europe. In an effort to tap into changing values around the redistribution of wealth, and aiming to co-opt communist ideals, in the late 1940s and 1950s elaborate welfare mechanisms were introduced. Drawing on the ideal types of sociologist Gøsta Esping-Anderson, three variants of welfare state can be discerned: (1) liberal welfare states characterised by a minimum involvement of the state (Britain, USA); (2) conservative models where the state is especially engaged in family-based assistance (e.g. Austria, Germany, the Netherlands, etc.); and (3) social democratic regimes where the state is considerably more involved in supporting social life (France, Belgium). Although Esping-Anderson’s classifications have received some criticism because many examples lay at the boundaries of or between these different regimes, it is still widely used as the main typology in research today. Although the countries of the Socialist Bloc and the Soviet Union do not fall within the more traditional definitions of the welfare state due to their illiberal democratic system, east of the Iron Curtain elaborate welfare systems based on Marxist ideals were also established and even lay at the heart of the raison d’être of these states.

Towards the end of the twentieth century reforms have dramatically eroded the welfare systems of countries both east and west of the Iron Curtain. From the late 1970s and especially the early 1980s, neoliberal ideas, at that time promoted in the US and UK, increasingly entered the political discourse in the democracies of continental Europe. Liberal parties, inspired by Reagan and Thatcher, explicitly questioned the dominance of the state in especially economic affairs and advocated for a greater freedom for the individual. By the 1990s, the logic of the market would stand central, and welfare programs and subsidisation policies would receive scrutiny (e.g. government involvement in key industries boosting employment such as coal mining). Many programmes were phased out for ideological reasons, but an underlying economic imperative also contributed to the disappearance of elaborate welfare programmes. Globalisation had been creating a race to the bottom, especially in industry. Tax incomes of states decreased, while states needed to cut taxes for large companies to deter them from moving their production to low-income countries with a more favourable tax system. The pervasive logic of the market also impacted social democratic parties (i.e. social democrats) who opted for a ‘Third Way’, where there would be still room for policies enabling egalitarianism, education and healthcare, while programmes geared towards redistributing wealth were rejected and phased out.

Following the collapse of the Soviet Union, many socialist countries were forced to embrace capitalism almost overnight. In effect, this meant that entire economic systems based on Marxist principles—and citizens who had lived in those systems—had to suddenly operate according to new, neoliberal principles. The rapid and unprepared privatisation of industry and the service sector had considerable impact on the welfare systems in place. Furthermore, parts of these systems were subsequently also privatised, triggering an almost total collapse of the welfare system. In both east and west the memories of the welfare state are diverse and often conflicting. Today the welfare systems of the post-war period are either remembered with nostalgia where there is a longing for state intervention and benefits, or on the other side of the spectrum more critical perspectives instantiate the welfare state as a critical flaw that is a root problem for the economic competitiveness of many social democratic and socialist countries.

Conclusion

The twentieth century experienced substantial demographic, geographic, and economic changes. These included the quadrupling of Europe’s urban population, a steady improvement in working conditions across the board—even if war, economic crisis, and globalisation dramatically affected the nature of work at different junctures throughout this period. Not least, this era saw tremendous changes in terms of family life, including reproduction, with dropping fertility rates in Europe at the dawn of the century and an increased focus on the family as a source of stability in the interwar and immediate post-war eras.

These developments, alongside growing grassroots political activism, increasingly powerful states, and potent new political ideologies, contributed to new movements to ‘engineer’ society in various ways. For some—like the British economist and politician William Beveridge (1879–1963)—the ‘welfare state’, with its comprehensive coverage from ‘cradle to grave’, could offer security in times of crisis, and over the usual life course. This view was not unique to liberal democracies like Britain, nor to Western Europe; vast social experiments and efforts to provide some form of social security extended across Europe, and beyond the Iron Curtain during the Cold War. From the late 1970s, however—and increasingly after the end of the Cold War—a move towards curbing the state and moving towards public-private partnerships in providing for ‘social’ goods became more prominent throughout Europe. This tension between public and private, and different ideologies of caring for issues related to the social sphere, continue to course through Europe in the present day, just as Europe itself continues to witness transformations in work, family life, and the environment, both urban and rural.

Discussion questions

- Which modern problems did the building of the ‘welfare state’ address?

- How did the development and the meaning of welfare systems differ in Eastern and Western Europe over the course of the twentieth century? Why?

- Do you think the construction of the ‘welfare state’ contributed to the development of a European identity? Why or why not?

Suggested reading

Castel, Robert, From Manual Workers to Wage Laborers: Transformation of the Social Question (New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers, 2003).

Esping-Andersen, Gøsta, The Three Worlds of Welfare Capitalism (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1990).

Quine, Maria Sophia, Population Politics in Twentieth-Century Europe: Fascist Dictatorships and Liberal Democracies (London: Routledge, 1996).

Thane, Pat, The Foundations of the Welfare State (Harlow: Longman, 1996 [1982]).

Wakeman, Rosemary, Practising Utopia: An Intellectual History of the New Town Movement (Chicago: Chicago University Press, 2016).