5.1.3 Entrepreneurs, Companies and Markets in Contemporary History (ca. 1900–2000)

© 2023 Halmos and Wieters, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0323.54

Introduction

From the perspective of business history, the conventional periodisation of a ‘long’ nineteenth century (1789–1914) and a ‘short’ twentieth century (1914–1989) is hard to maintain. Business cycles have their own logics that often do not overlap completely with political developments. Arguably, the starting point of the modern world market was the Panic of 1873 that led to economic depression in the United States (US), Austria-Hungary, Germany, France, and Britain. The magnitude of the crisis of 1873 was eventually surpassed in 1929 by the Great Depression, which subsided only with the preparations for the Second World War. The subsequent decades of economic growth were cut short by the so-called oil crisis in 1973, which caused a worldwide depression. The last crisis of that magnitude was the 2008 crash of the US mortgage securitisation market. All these events shaped the development of the modern European economy, and provide markers for a different periodisation of economic history. That said, the major events of the twentieth century—the First and Second World Wars, the Cold War and its end—did have a transformative influence on economic development in Europe.

The Development of the Firm in Twentieth-century Europe

In Europe, the modern managerial firm did not become the dominant form of industry until the end of the Second World War. According to business historian Alfred D. Chandler Jr., the modern enterprise is not only a place for production—it is also an organisation for the distribution of products. The essence of this new institution was effective contract governance and managerial organisation. However, this modern form of enterprise mainly developed in North America, where markets were far away from their suppliers.

The nation-state system in Europe did not allow for the establishment of a single market similar to the United States. Not only were markets territorially fragmented, but consumers were also not as far from producers as they were in the American case. There was no need for a manufacturing firm to control the sales of their own products. Production (processing and manufacturing) firms as well as commercial ones (trading houses) were detached from each other and there was no serious need to integrate the productive and the commercial functions. Family firms were—and still are—much more common in Europe than in the United States.

This started to change during the first half of the twentieth century. While the nineteenth-century economy had been characterised by the concentration of the factors of production, i.e. land, labour, and capital, the First World War and the Great Depression complicated this process. While the tendency of conglomeration—i.e., business enterprises getting bigger and bigger—was obvious on both sides of the Atlantic, the reactions to that tendency were different. In North America anti-trust laws were introduced and enforced. On the European continent, cartels (a form of restricting competition) were not abolished: on the contrary, coordination between enterprises in certain sectors was openly encouraged and developed.

The fact that capitalist economies differed in Europe and the United States raised the question of which model was better—that is, which model was more stable, more functional, and better for society as a whole. There were, however, no simple answers, even though economists across the globe debated this issue, and economic theory throughout the twentieth century very much centred on the question of how to build stable and prosperous economic systems.

Command Economies in Eastern Europe

In the context of the First World War, governments across the globe started to introduce strict measures to regulate national and international markets. Tolls were introduced or raised, taxes increased, and import and export quotas were enforced to protect national markets and to ensure that supply chains for important goods were upheld. After the war, revolutionary movements gained in strength across Europe, especially in the countries that had lost the war. In terms of business relations, many of these revolutionary movements and parties were rather conservative and argued for even tighter market regulations and government-enforced economic measures.

The most important case was that of Russia and, later, the Soviet Union. During the Russian Civil War (1917–1923), the Bolshevik revolutionaries set up the system of so-called ‘war communism’, characterised partly by the overwhelming power of the state (labour duty, requisitions, bans on private enterprise) and partly by government-run intra-firm management to secure the supply of the army, control foreign trade, enforce strict labour discipline, and implement strict coordination between productive units.

The experiment in war communism ultimately failed, mainly because of a lack of cooperation and support from the peasants, who were not fully integrated into the national market system, and because—in the long run—productivity was too low to secure provisions and prevent food shortages in the urban centres. To tackle the looming food crisis and to push the rapid industrialisation of the country forward, the Soviet government eventually introduced collectivisation—a policy that forced nomads (e.g., in Kazakhstan) to settle down as farmers, and the peasants in the Soviet empire (e.g., in the Ukraine) to give up their individually-used farms and join large collective agricultural units. Historians such as Robert Kindler and Robert Conquest have convincingly argued that these measures led to severe and recurring famine and may have cost more than 1.5 million lives.

Collectivisation went hand-in-hand with industrialisation, and in 1928 the first five-year plan (pyatiletka, 1928–1932) was introduced. This system of command economy—where the economic plans were de jure laws and not fulfilling them was an infringement of the law—was later expanded to the economies of post-World War Soviet satellite states in Eastern Europe. The system lasted until the collapse of the Eastern/Soviet Bloc in 1989–1991. While Soviet command economies seemed to be working for a while, especially—as economic historians such as Eric Hobsbawm and others have argued—in the context of crises, wars (especially the Second World War), and during reconstruction, economic performance soon diminished. From the 1960s onwards, it became apparent that neither their productive capacities nor their stability and ability to fulfil public demand for goods and services could in any way compete with the economies in Western Europe and the United States. Hence, from the 1970s onwards, most planned economies were sliding from crisis to crisis.

The Marshall Plan and the Reorganisation of Western Europe

The Second World War and its aftermath transformed the economies and markets of Western Europe. It has been argued that, in many ways, they became more American: countless US consumer products were in high demand and many techniques from both production and marketing were adopted in Europe.

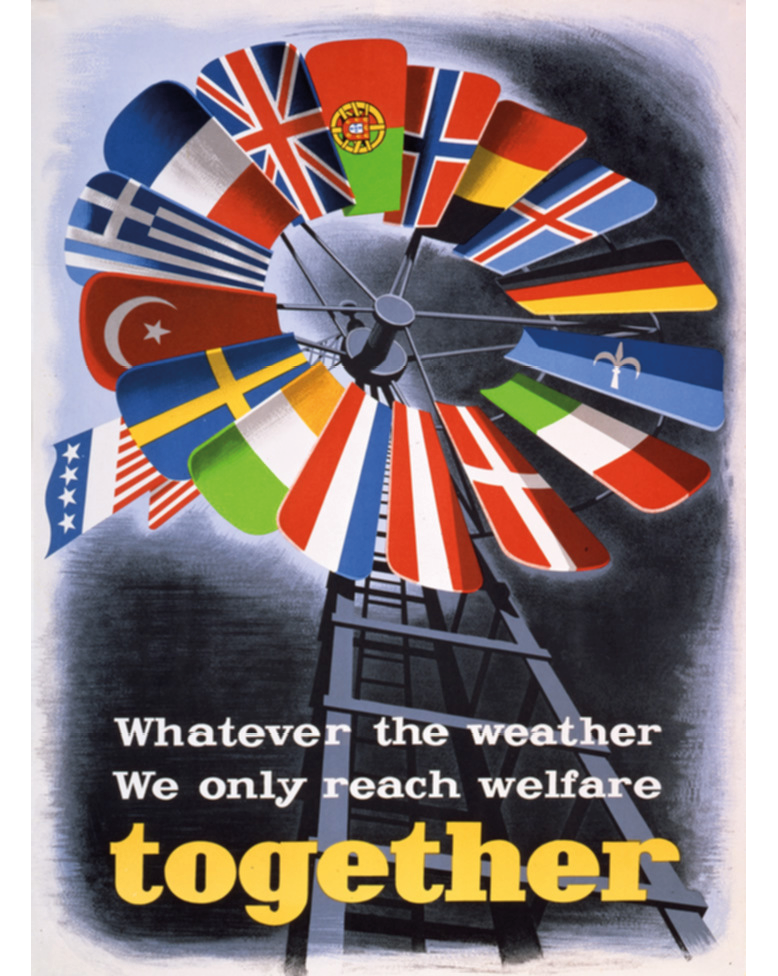

Fig. 1: E. Spreckmeester, “Marshall Plan poster” (1950), Wikimedia Commons (from the Marshall Foundation), https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Marshall_Plan_poster.JPG. This poster was created by the Economic Cooperation Administration, an agency of the U.S. government to sell the Marshall Plan in Europe. It includes versions of the flags of those Western European countries that received aid under the Marshall Plan (clockwise from top: Portugal, Norway, Belgium, Iceland, West Germany, the Free Territory of Trieste (erroneously with a blue background instead of red), Italy, Denmark, Austria, the Netherlands, Ireland, Sweden, Turkey, Greece, France and the United Kingdom). The poster does not explicitly depict Luxembourg (whose flag is very similar to the Dutch flag), which did receive some aid.

Both during and after the Second World War, the European economies, which had hitherto been at the centre of global commerce, decreased in importance and standing relative to the economy of the United States. On the continent, both winners and losers of the Second World War were heavily indebted (mostly to the American government) and large parts of the remaining European infrastructure was either in ruins or outdated. The United States filled the void and used its new dominance to shape the recovery of the European economy through, for example, the European Recovery Program (ERP), better known as the ‘Marshall Plan’, after the American Secretary of State George C. Marshall (1880–1959). The Marshall Plan was a system of economic aid that ran from 1948–1951 and was worth 12.4 billion USD (about four percent of the annual average US GDP at the time). The aid was not a loan and the countries that signed up to it did not have to repay any money. They were required, however, to rebuild, reorganise, and modernise their economies and financial systems along the lines of the American model. They also agreed to cooperate closely in terms of financial and trade flows. The aid was nominally offered to the whole of Europe, but Soviet leader Joseph Stalin (1878–1953) banned Eastern European satellite states from participation. While opinion is divided among economic historians about the final impact of the Marshall Plan in the recovery of the war-torn European economy, it did harmonise the continent’s markets outside the ‘Iron Curtain’ and created incentives to establish a free market based on multilateralism. Under the given circumstances, this system gave an advantage to countries that could supply trade with generally accepted currency, viz. the US. While this made the American form of business organisation, including a managerialisation (separation of ownership and leadership) of enterprises, more attractive for European business actors, family firms (uniting ownership and leadership) remained a characteristic element of the European business environment.

The Appeal of State Intervention in the West

Although it is common to refer to the post-war party-state countries in the Soviet sphere with planned, command and control economies as ‘socialist’, Western European countries also found some forms of state intervention attractive. This could include actual nationalisation, as was the case in Britain with the coal mines in the case of industry, the railways in the case of material services, and the health insurance system in the case of non-material services. In France, several large banks and companies were deemed to have been collaborators during the war and were nationalised after 1945 on those grounds. Elsewhere, state intervention meant state planning—not instructional planning—as in France and the Netherlands. The countries of the Iberian Peninsula that remained neutral during the war, as well as Italy, were characterised by the survival of corporatism. The free-market system was most prominent in West Germany, where the system of state intervention was gradually replaced after the war by a system of so-called ‘ordoliberalism’ based on market order. According to ordoliberalist thought, the state should not only create the necessary conditions for a free-market economic order with competition, but also maintain it. In ordoliberalism, the preservation and safeguarding of free competition is served by the creation of a legal framework by the state.

European Integration and the Single Market

In addition to the external impetus of the Marshall Plan, the integration of the Western European economies was also fostered from within. Next to countless international organisations focussing on international (and European) commerce and labour relations, such as the Organisation for European Economic Cooperation (OEEC; today OECD), or the International Labour Organization (ILO), the European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC) was founded in 1951. With the Treaty of Paris, the signees Belgium, France, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, and West Germany decided to jointly regulate their coal and steel industries. The ECSC was headed by a joint (tripartite) high authority and is often seen as one of the first cornerstones of even deeper European market integration. This deeper European market integration continued more officially with the establishment of the European Economic Community (EEC) and the signing of the Treaty of Rome in 1957, which declared the ambition to “lay the foundations of an ever closer union among the peoples of Europe”, to ensure the economic and social progress of their countries by common action to eliminate the barriers which divide Europe”, and to remove “existing obstacles” to eventually “guarantee steady expansion, balanced trade and fair competition”, among other goals.

While the member states had originally planned to form three joint communities—the EEC, the European Atomic Community, and a Joint European Defense community—the latter could not be realised as no agreement could be found on how to proceed. Hence, much focus was placed on creating a jointly regulated European market without tolls and with easier import/export regulations between the partners.

As (economic) historians such as Barry Eichengreen, Kiran Patel, and others have shown, there is considerable debate on how much the EEC contributed to the European ‘Trente Glorieuses’—meaning the thirty-year period of prosperity and rapid economic growth in most economies in Western Europe and beyond following the Second World War—especially given the countless other global economic networks the six member states were also involved in during this era. There is wide agreement, however, that despite countless crises (such as the ‘end of the boom’ in the 1970s, the two oil crises and various economic slumps, including the latest financial crises after the turn of the millennium) the process of creating a single European market, aimed at eventually facilitating the ‘four freedoms’—meaning free movement of goods, service, people, and capital—has significantly deepened European economic cooperation and standardisation.

The single European market currently comprises twenty-seven member states which hold privileged trade relations with many external partner countries across the globe, making the European market one of the largest and most stable projects of economic integration worldwide. A joint currency was agreed upon in the 1990s and was introduced in January 2002 by twelve member states that met the jointly agreed criteria. Other members joined the currency union in the following years, and the Euro is currently used in nineteen European states.

The Collapse of Command Economies and the Transformation of Eastern Europe

The economic systems of Eastern Europe prior to the collapse of communism were seen in these countries as having eliminated the exploitation and loss caused by market fluctuations. The cost of this was that the production units operated without real owners. The state bodies that managed the assets of the companies were in fact acting on behalf of non-existent proprietors. However, these planned economies, and the cooperation between them, were characterised by inefficiency. Socialist companies and production plants had few and tenuous links with their markets, and the movement of capital was not regulated by the market but by a system that worked by taking the profits of successful companies and transferring them to less productive ones, under the pretext of the principle of responsibility to supply. The principle of redistribution was also used in the context of international business relations between the planned economies. The institutional framework of this system was the Council for Mutual Economic Assistance (Comecon), founded in 1949 as a response to the recovery efforts of the Marshall Plan and the formation of the OEEC. Its dominating political power, the Soviet Union, supplied the satellite Comecon states with relatively cheap energy and the latter delivered agricultural and industrial products to the rather undemanding Soviet market.

After the collapse of the Soviet Union, there was a desperate search for alternative proprietors. One of the extreme cases among the small Comecon countries was that of East Germany, the provinces of which joined West Germany, accepting the political and economic constitution of its erstwhile rival. Other countries tried different solutions. In Poland, the so-called ‘Balcerowicz Plan’, named after Leszek Balcerowicz, the finance minister of the country’s first non-communist government, introduced a programme of ‘shock therapy’, withdrawing the guarantee of existence for all state-owned companies and allowing investment by foreign companies and private people. Some countries reprivatised confiscated real estate, but if a government did not find this feasible, there was still the possibility of compensation via marketable bonds. In most cases, what happened was a rapid concentration of capital in the hands of a few. The solutions proved to be relatively well-accepted by the constituent populations of these countries who were facing a transformation crisis the magnitude of which was comparable to that of the losses during the Second World War. Some of these countries found some relief by joining the European Union (created from European Economic Community in 1993), since this offered the new members access to resources in the form of direct investments and modern technologies. At the same time, the opening of non-consolidated markets to the old members of the Union did also come with liabilities. As for the foreign markets of these post-communist states, after the collapse of the Soviet market, the German-speaking countries often assumed a leading role in their foreign trade—returning to the predominant pattern prior to the Second World War.

Conclusion

Looking at the roles of entrepreneurs, companies, and markets in the ‘long’ twentieth century, it can be argued that developments have been shaped by both globalisation and ‘localisation’—or rather regional differentiation processes. While the differences between the command economies in Eastern and South-Eastern Europe and the market economies in Western, Northern and Southern Europe are certainly one of the most visible economic rifts that shaped the economic history of the twentieth century, it is still necessary to take a closer and more nuanced look at the many regional differences on both sides of the ‘Iron Curtain’. Capitalist economies in Europe were neither uniform nor convergent, and they were also not simply modelled on the US—even though many American trends and practices were adapted and integrated into the European economies. Despite international exchange and globalising tendencies, European economic relations, capitalist markets, and entrepreneurial traditions remained very much dependent on local conditions and traditions. This included—and still includes—government interventions, market regulations, economic planning as well as cartels and corporatist arrangements to varying degrees. The same can be said for the command economies in (South-)Eastern Europe. Socialist approaches to tackling industrialisation, economic growth, and provision of the population were also highly varied and diverse in the different countries of Eastern Europe. While productivity was generally lower than in the market economies of the West, provision, welfare and distribution of goods were organised differently in these countries.

Having said that, both socialist and capitalist economies struggled with recurring economic crises—on the regional, the national, and the international levels. While, in the long run, productivity was too low to satisfy public demand for many goods in most command economies, the capitalist economies were confronted with recurring economic crises as well: the oil and financial crises of the 1970s demanded new international models of economic cooperation and showed the vulnerabilities of the capitalist economies in a globalising world. European integration and the creation of the European single market was one pillar of building more stable and interconnected markets and stronger economic ties between European economies. But there are also other international agreements, such as the European Free Trade Association (EFTA) or the General Agreement on Trades and Tariffs (GATT), which were forged to help regulate markets across borders. After the end of the Cold War and the transformation of former command economies into new market economies, European economic relations and markets have both consolidated and become more interdependent—especially in the context of the European single market. Yet, as recurring economic crises have shown, market economies in Europe (and beyond) remain prone to instability and disequilibrium—rendering permanent political cooperation, market regulation and economic intervention a necessity.

Discussion questions

- Was European integration and the development of the European single market inevitable after 1945?

- Why did a different economic system characterised by command economies develop in Eastern Europe?

- In 2021, the United Kingdom left the European single market. Do you think this was a good decision? Why? Why not?

Suggested reading

Beckert, Jens, Imagined Futures: Fictional Expectations and Capitalist Dynamics (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2016).

Berghoff, Hartmut, Moderne Unternehmensgeschichte: Eine themen- und theorieorientierte Einführung (Paderborn: Ferdinand Schöningh, 2004).

Chandler, Alfred D., The Visible Hand: The Managerial Revolution in American Business (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1977).

Eichengreen, Barry J., The European Economy since 1945: Coordinated Capitalism and Beyond (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2008), https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctt7rpfs.

Hobsbawm, Eric J., The Age of Extremes: A History of the World, 1914–1991 (New York: Michael Joseph, 1994).

Jones, Geoffrey, ed., The Rise of Multinationals in Continental Europe (Aldershot: Elgar, 1993).

Jones, Geoffrey, The Evolution of International Business: An Introduction (London: Routledge, 1996).

Kindler, Robert, Stalin’s Nomads: Power and Famine in Kazakhstan (Pittsburgh, PA: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2018).

Müller, Philipp, Zeit der Unterhändler: Koordinierter Kapitalismus in Deutschland und Frankreich zwischen 1920 und 1950 (Hamburg: Hamburger Edition, 2019).

Patel, Kiran Klaus, Project Europe: A History (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2020).

Raphael, Lutz, Jenseits von Kohle und Stahl: Eine Gesellschaftsgeschichte Westeuropas nach dem Boom (Berlin: Suhrkamp, 2019).