5.3.2 Production and Consumption in Modern History (ca. 1800–1900)

© 2023 Janáč, Klement, and Wieters, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0323.59

Introduction

At the beginning of the nineteenth century, Europe (and especially its northwestern part) emerged as the global economic core, at the centre of long-distance trade routes connecting virtually all continents around the globe. Over the previous centuries, Europeans consolidated their position in the world economy and accumulated wealth without actually producing goods of particular interest to other parts of the world, instead enriching itself by trading products originating out of Asia, Africa, and America. The European position within global trade networks contributed to specific circumstances which gave rise to industrialisation and modern economic growth. Relatively high wages (when compared to the rest of the world) and a relative abundance of goods coming from overseas created a pressure towards transformations of production and consumption patterns—known as mechanisation and industrialisation—which in turn helped to create conditions for transition towards the sustained economic growth associated with industrial capitalism. Initially located in areas along the Atlantic Coast, the transition soon affected even the most distant corners of the continent. However, the spread of industrialisation and modern economic growth produced important spatial inequalities. The differentiation of the European territory followed the North-West South-East gradient, with western countries adopting changes more quickly (around the 1850s) and becoming the economic core, while Eastern and Southern Europe reacted more slowly, and rather than developing industrialisation instead provided agricultural products for the West.

Economic Growth

Economic historians of Europe generally interpret the nineteenth century as a period marking the decisive transition from the traditional growth model to modern economic growth. While the former essentially corresponded with Malthusian principles (i.e., economic growth was tied to population growth due to relatively stable labour productivity, with population growth further limited by available resources), the latter was based on rapid acceleration in the efficiency of production (thanks to growing labour productivity) and significant structural changes (for example, shifts from agriculture to industry and services, or from individual entrepreneurs or workers to large firms and corporations). There were indications that the ‘Malthusian trap’—a theory from English economist Thomas Robert Malthus (1766–1834) that growth was ultimately and inevitably capped by limited access to finite resources, particularly food—was being broken. These indications first appeared in the North Sea region of Europe in the eighteenth century, but the escape from the ‘Malthusian trap’ remains generally associated with the onset of the industrial revolution and industrialisation in Britain. Indeed, available evidence suggests that prior to that moment of industrialisation, incomes tended to fluctuate from place to place and year to year, but due to stable productivity did not generally trend upwards.

The new conditions emerging in Britain did not escape the eye of contemporary observers. Even prior to Malthus, Adam Smith (1723–1790) articulated a theory of economic growth capturing the change unfolding before his eyes. What he witnessed in Britain and described in his theory was a rise in labour productivity by means of the division of labour (specialisation), which depended on previous accumulation of wealth enabling investments necessary for increasing specialisation. What is important to note here is that Adam Smith articulated his thesis without referring to the early results of industrialisation, thus—rather than addressing technological change—he highlighted the emerging institutional framework of commercial capitalism.

It was only the combination of industrialisation (the mechanisation of production) and capitalism that really triggered the historically unprecedented era of continuous economic growth in Britain and later in the rest of Europe. Over the last few decades, economic historians have corrected often exaggerated estimations of scale of growth in the British economy during the Industrial Revolution, arguing that even in Britain the change was gradual and evolutionary rather than revolutionary in nature. (That is why industrialisation rather than Industrial Revolution is a more appropriate term for the process.) Also, the initial belief in the significant role of industry and technological change in triggering growth has somewhat waned recently, with institutional frameworks now being heralded as the crucial variable in the onset of industrial capitalism.

Between 1700–1870 the transition to sustained modern economic growth spread across the continent, from Britain first to Western Europe: beginning from the 1840s, Belgium, the German states, France, and the Netherlands all launched their particular versions of industrialisation. In Southern and Eastern Europe, however, growth remained limited to pockets in Spain and Northern Italy until the late nineteenth century, while territories East of Germany generally witnessed the arrival of industrial capitalism in the agricultural sector, due to their orientation toward supplying the West.

Besides the spatial differentiation, growth also showed considerable variation over time. Contemporary economists were quick to recognise patterns in such fluctuations, and identified their cyclical nature based on their analysis of prices. First, Clement Juglar (1819–1905) described trade cycles of seven to nine years, followed by Nikolai Kondratiev’s (1892–1938) sixty-years-long waves, associated with demographic data and technological innovations. Indeed, prices in the now relatively integrated European market witnessed similar long-run trends. While prior to the 1800s such cycles were much shorter (with downturns appearing every three to four years) and instances of sustained growth over a period of several years were rather scarce, with the transition from agriculture to trade and manufacturing as leading economic sectors, cycles of growth extended initially to about six years and downturns were—under these conditions—of relative, rather than absolute, nature as before. However, the stabilisation of modern economic growth on the continent brought steeper swings from the 1870s on: decline between the mid-1870s and mid-1890s (the period of the so-called ‘Long Depression’) was substituted by rapid growth associated with high inflation prior to the First World War (the so called ‘Belle Époque’).

Industrialisation: Productivity, Innovation, Production

This economic period was long called an ‘industrial revolution’ based on the scale of significant economic change it saw. Referring to it as a revolution evoked the rapid and drastic nature of the change and transformation taking place in industry, which was similar in consequence to the social change caused by the French Revolution. As noted above, it has now become commonplace among economic historians to argue that industrialisation is a more appropriate term to describe this change. Economic growth was not of such a rapid and radical scale to justify the revolutionary marker, but was rather a long-term, sometimes fluctuating, but continuous change.

The nineteenth century was an era of industrialisation throughout Europe, although in England the process began as early as the mid-eighteenth century. European countries did not progress in industrialisation at the same time, at the same pace or in the same way, but by the nineteenth century—in one way or another—the change had already reached all European regions. Industrialisation as a process saw the population, which until then had mainly lived off agriculture, take jobs in industry in increasing numbers, and also saw the relative importance of industry in production grow. Industrialisation is thus a phenomenon of both social and economic transformation. The more the process of industrialisation progressed in a country, the more the number of people employed in industry increased and the number of people dependent on agriculture decreased.

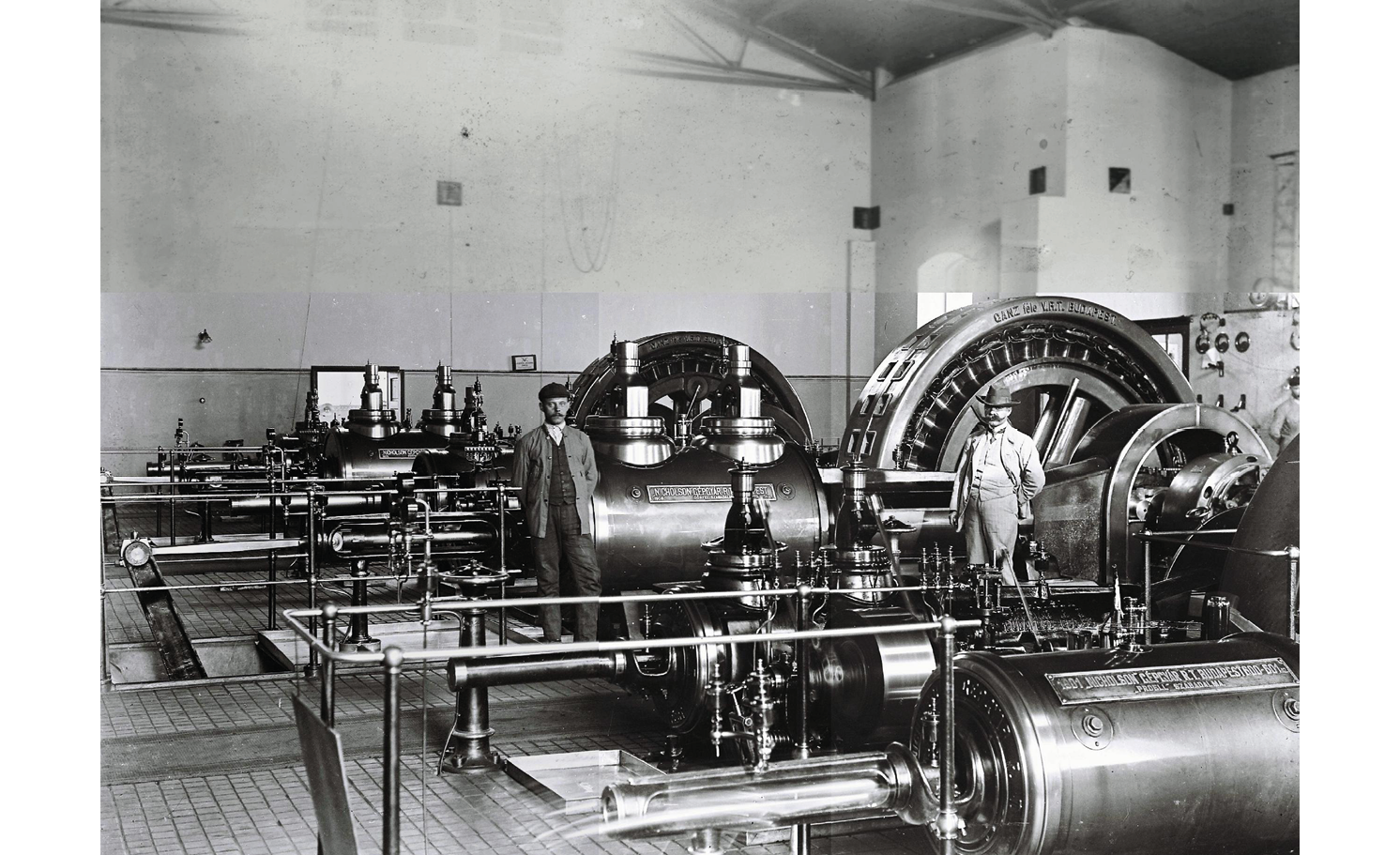

Fig. 1: Steam engines, Nicholson Machine Factory, Újpest, Hungary (1914) Somkuti Ágoston / Fortepan 211141, https://fortepan.hu/hu/photos/?id=211141.

As a result of industrialisation, economic growth was no longer restricted. One source of this economic growth was increasing productivity—i.e., in the nineteenth century a worker produced significantly more products in the same amount of time relative to earlier eras. Beside the division of labour, another reason for the improvements in productivity were technical developments and innovations utilised in production. Scientific and technological innovations spread slowly through the economy as a whole, and initially the textile, iron, and steel industries in particular were at the forefront of technological innovation. Nonetheless, during the nineteenth century, slowly, all sectors of the economy were transformed by technical developments even beyond industrial production itself. The invention of the steam engine (1769)—seen by some as the starting point for industrialisation—is a good example of how the impact of innovation spread across the economy as a whole. The steam engine enabled mechanised mass production in industry, and transport (and thus trade) was revolutionised by its use in the steamboat and especially in the steam locomotive (1814). But agricultural production was also transformed by the steam plough—which enabled the mechanisation of ploughing—and especially by the steam threshing machine (1849), which enabled the mechanisation of grain threshing.

In fact, without an increase in agricultural productivity, industrialisation would not have been possible. Workers were able—and had—to leave agriculture and make a living from industry in increasing numbers: agricultural productivity improved, so even fewer hands were necessary to increase agricultural production which, in turn, rendered additional agricultural workers surplus. The development of agricultural productivity was made possible by crop rotation, the use of iron tools, seed selection, stable livestock farming, fertilisation (later chemical manure) and the mechanisation of certain work phases, such as threshing and ploughing. Although the development of agriculture made industrialisation possible, its progressive industrialisation also had repercussions, as a growing (primarily urban) population engaged in industrial labour had to be provided with food. Thus, industrialisation resulted in increasing demand for agriculture, encouraging further increases in agricultural productivity.

Industrial production also underwent significant transformation during industrialisation. Former handicraft production was gradually replaced by the manufactory industry, and from the beginning of the nineteenth century, an increasing number of factories appeared. Factory production—as a new institutional form of production—meant a division of labour, mechanised production with a much larger number of workers (into the thousands), using machines driven by steam power (later electricity). Factories also enabled the mass production of goods, which reduced the price of industrial products and made them available to a wider range of consumers. This, in turn, had a significant effect on the culture of consumption. In addition to a larger workforce, mechanised large-scale production required much more capital, as the acquisition and operation of machinery, the maintenance of factories, and the use of a larger labour force significantly increased the financial resources required by industry. The higher need for capital in the age of industrialisation resulted in the spread of joint-stock companies, where the cost and risk of production were shared among several shareholders. However, the joint-stock company was important not only as a new source of capital but as an institutional innovation of capitalism itself. The division of labour and the specialisation of all work processes (i.e., not only production) characterise the operation of a joint-stock company. This also allows effectiveness in highly complex workflows (for example, in corporate governance and control) and enables diverse activities, such as the mass production of a wide variety of products or simultaneous sales on different markets. British Economist Ronald Coase pointed out (The Nature of the Firm, 1937) that the joint-stock company reduces transaction costs—namely the costs of operating on the market—when a task is solved not from the market but within a company itself; an example of such a manoeuvre would be for a firm to set up a marketing and sales department rather than entrusting sales to a dealer.

In the age of industrialisation, the growing capital needs of economic actors together with the escalating risks of production brought to life the modern banking and insurance sector. The (classic) English commercial banking services were limited to deposit collection and short-term lending. During the nineteenth century, the range of activities of credit institutions and insurance companies considerably grew. One nineteenth-century development was the emergence of universal banks, which could take part in the establishment of companies by providing long-term loans, and in their operation as shareholders as well.

Consumption

When it comes to consumption, the nineteenth century was not necessarily as ‘long’ as historians have claimed it to be in other respects. Cross-border markets and modern European (and as such highly interwoven) consumer societies started to emerge in the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries. Goods such as coffee, tea, cocoa, and spices became available for wider segments of society, and newly fashionable clothing and accessories were created. These new consumer styles and the demand for the respective goods often traversed borders of social status. In their free time, servants sometimes found joy in wearing clothes adapted to models worn by people from the upper classes, and small accessories such as feathered hats were tailored to imitate objects formerly worn by the nobility. Oriental rugs or new fabrics such as chintz and calico (printed cotton from India) ultimately created new demand for certain goods which—as has been argued—incentivised industrialised production even further.

The industrial revolution was accompanied or even preceded by an “industrious revolution” (Jan de Vries), meaning that many citizens were ready and able to work more in order to fulfil their cravings for certain goods and services. This dialectic process—connecting cultural, mental, and economic transformations—certainly accelerated in nineteenth-century Europe. Due to rapid urbanisation, both a growing bourgeois ‘middle-class’, and an increasingly mobile labour force made their imprint on growing cities. Subsistence farming and closed household economies—that had once contributed to the everyday sustenance of many families—vanished fast. Mass consumption became an increasingly everyday reality, and necessitated the purchase of almost all household goods including food, clothes, pottery, and toiletries. While small shops emerged everywhere—particularly in the inner cities and around those quarters where people lived in close proximity—warehouses were built in the outer quarters. These wholesalers set out to reorganise the retail sector in the cities, especially as new ways of packaging goods in smaller batches were invented.

Towards the mid-nineteenth century, department stores opened in big cities and emerging metropoles. France was a European forerunner. Fashionable department stores such as Au Bon Marché in Paris presented wide assortments of both every day and luxury goods—incentivising consumers, especially women, to take a stroll through the display sessions and buy the goods that came in different qualities across a wide price range. Even for those not well-off enough to afford these goods, window-shopping became a cherished pastime that created aspirations and further incentivised consumer behaviour and culture. In his great European novel Au Bonheur des Dames (1883), the French writer Émile Zola tried to capture the excitement visitors to these new kind of shops were experiencing: “And there, in that chapel dedicated to the worship of feminine graces, were the clothes: occupying the central position there was a garment quite out of the common, a velvet coat trimmed with silver fox; on one side of it, a silk cloak lined with squirrel; on the other side, a cloth overcoat edged with cock’s feathers […]. There was something for every whim, from evening wraps at twenty-nine francs, to the velvet coat which was labelled eighteen hundred francs.” (Zola, The Ladies’ Paradise,. Translated from the French original by April Fitzlyon. [Alma Classics Ltd 2013], p. 6.)

Those who could not save enough to buy the objects of longing were increasingly relying on credit. While private borrowing (often based on long established relations of trust) has a long history and had been done for centuries, from the mid-nineteenth century onwards, the first consumer credit models were also offered. Consumer credit could mostly be obtained in smaller shops, but slowly credit associations and other financial brokers also joined this new market.

This process was accompanied by new marketing techniques and shifts in advertising, which also increasingly included hints on how to afford and finance these goods. The rise of the print media in the second half of the nineteenth century offered new ways to publicise consumer goods and create objects of longing for consumers in Europe and beyond. Fancy packaging or artsy and colourful presentations of goods in newspapers and magazines helped shape distinct consumer societies in Europe and created more complex business cycles involving a growing variety of professions.

While many goods—especially certain luxury objects—were still mostly affordable only for the middle- and upper-classes, being a part of the emerging consumer society was no longer a privilege for the rich. Throughout the nineteenth century, consuming became something that defined and shaped the everyday life of European citizens in the cities as well as in the countryside. Consumerism became an integrative force both connecting and distinguishing Europeans across social strata as diverse consumer cultures emerged.

Conclusion

During the nineteenth century, the frameworks of production and consumption changed fundamentally. Specialisation (a division of labour), technical innovations, and institutional changes transformed production: productivity increased significantly, and industrial production in factories—using machines and power machines—as well as mass production, became commonplace. Productivity growth was characteristic of both agriculture and industry. This was the era of industrialisation, a period when first industry, and later the service sector became more and more important within the economy. Along with sectoral change, the number of persons employed in industry, and subsequently in the service sector increased, while those living from agriculture decreased. The age of industrialisation also transformed trade and consumption. Department stores, commercial specialisation, and mass consumption emerged. As part of these economic transformations, a modern banking and insurance sector developed.

This process characterised the whole of Europe, however the commencement, pace, and course of industrialisation varied in different parts of the continent. In England, industrialisation began as early as the eighteenth century, followed by the countries of Western Europe in the early nineteenth century. The industrialisation of Eastern and Southern Europe started later, as their production was initially dominated by the growing demand for food from the West. This also signalled the extent of globalisation, the interconnection of markets.

As a result of industrialisation, economic growth was able to step out of the ‘Malthusian trap’: growth was no longer limited but rose and fell in new economic cycles. The second half of the nineteenth century was defined first by the ‘Long Depression’ then—before the First World War—by the ‘Belle Époque’.

Discussion questions

- What role did industrialisation play in production and consumption regimes in nineteenth-century Europe?

- In which ways did the development of production and consumption regimes differ in Eastern and Western Europe?

- In which ways did developments of the nineteenth century shape the consumer society today?

Suggested reading

Broadberry, Stephen and Kevin H. O’Rourke, The Cambridge Economic History of Modern Europe, vol. I: 1700–1870 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010).

Haupt, Heinz-Gerhard, ‘Consumption History in Europe: An Overview of Recent Trends’, in Decoding Modern Consumer Societies, ed. by Hartmut Berghoff and Uwe Spiekermann (New York: Springer, 2012), pp. 17–35.

Stearns, Peter N., ‘Stages of Consumerism: Recent Work on the Issues of Periodization’, The Journal of Modern History 69:1 (1997), 102–117.

Fouquet, Roger and Stephen Broadberry, ‘Seven Centuries of European Economic Growth and Decline’, Journal of Economic Perspectives 29:4 (2015), 227–244.

Logemann, Jan, ed., The Development of Consumer Credit in Global Perspective: Business, Regulation, and Culture (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012).

Vries, Jan de, The Industrious Revolution: Consumer Behaviour and the Household Economy, 1650 to the Present (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009).