1.3.1 Migration in Early Modern History (ca. 1500–1800)

© 2023 Behrisch, Graf, Horn, and Rodríguez García, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0323.07

Introduction

Living in the twenty-first century, we often think that we inhabit an age of unprecedented mobility. As a result of the technical innovations of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries—such as railways, steam ships, the automobile, air travel, and communications technologies like the telephone, the telegraph, and the Internet—we have dramatically increased the speed of communication compared with that of the physical conveyance of written messages in earlier times. Mobility and migration, however, were already omnipresent in the early modern period, both within Europe itself and between Europe and other parts of the world, such as Asia and the Americas. In fact, the frequency of migration may have been even higher than in today’s world of nation-states and potentially closed national borders, even if movement itself—on foot, on the backs of animals, or aboard sailing vessels—was much slower. Some historians have described a marked increase in geographic mobility on a global scale as one of the defining characteristics of a global early modernity.

One major reason for this high degree of mobility was the fact that, throughout the early modern period, Europe was a patchwork of relatively small territories and cities, many of which were de facto autonomous. This situation created not only opportunities and incentives for migration—as skilled labourers, for example, sought employment elsewhere—nascent states had only very limited abilities, resources, and information to restrict movement across the borders of their territories, even when they wanted to do so. Nevertheless, early modern governments had a significant impact on the movement of people. Cities—and capitals, in particular—attracted people who could meet the governments’ demands for soldiers, administrators, entrepreneurs, and other specialists. Especially following the Thirty Years’ War (1618–1648), moreover, rulers in Central Europe in particular attracted people of talent not only to repopulate their territories, but also to develop local economies and enhance cultural life, all vital sources of prestige and power. On the other hand, restrictive and repressive measures against religious minorities and beggars would cause them to seek refuge elsewhere and military conflict likewise displaced large numbers of people. Migration clearly was not always voluntary, but frequently the result of circumstance and even outright force. This chapter uses the specific lenses of religious migration, expulsion, warfare, and coerced migration to explore the range of contexts, directions, and occasions for early modern people moving within Europe and beyond.

Religious Migration and Diasporas in Early Modern Europe

Religious and confessional minorities were the most conspicuous migrants in early modern Europe, although they may not have supplied the largest overall number of migrants. As they migrated across the continent, many of them settled permanently in another place. If they shared that place’s confession (or else converted to it), they usually assimilated quickly. This is true for most migrants adhering to one of the main (and in most states the official) confessions—Catholic and Lutheran (or Anglican)—who mostly found refuge in states or cities of the same confession. Where migrants did not share the host society’s confession, however, they formed diasporas that would keep their cultural and linguistic identity over generations, too.

Religious migration took on many different forms during the early modern period, and it is hard to determine a beginning and end or to single out specific phases. Jews had started to flee from Spain since the forced conversions and massacres of the early fifteenth century. During the same period, Jewish communities in Italy and in the Holy Roman Empire, too, were maltreated and/or expelled. Many resettled in Poland and Lithuania—where they faced a similar fate in the seventeenth century, while being allowed back into England and France, from which they had been banned during the Middle Ages. Large numbers of Iberian Jews also found new homes in the Ottoman Empire, notably in Istanbul and in present-day Thessaloniki. The Protestant Reformation triggered the migration of Lutherans from Catholic territories and vice versa, as well as—from the middle of the century onwards—the migration of Calvinists from both. The Calvinists’ greatest tribulations, however, occurred in the seventeenth century, when the Habsburgs re-Catholicised their Bohemian and Austrian lands in the wake of the Thirty Years’ War, and the French king, Louis XIV (1638–1715), drove more than 100,000 ‘Huguenots’ (Calvinists) out of France. At the same time, the Reformation had triggered a continuous splintering of Protestantism into ever smaller denominations—from Swiss, German, and Dutch Anabaptists in the 1520s to the Quakers in the following century. Most of them survived in disguise, thousands of them perished, and tens of thousands fled abroad, where they were regularly tolerated as a foreign religious minority, i.e. a diaspora. The Principality of Transylvania, an Ottoman vassal but with complete internal freedom, deserves special attention: uniquely in Europe, four confessions (Catholic, Lutheran, Reformed, Unitarian) were officially accepted, while Orthodox Christians and Greek Catholics were allowed to practise their faith, as were Jews and other religious minorities, including radical Protestants such as Anabaptists and Sabbatarians who were expelled from almost everywhere else in Europe.

More generally, however, religious diasporas became an important phenomenon in early modern Europe—more so than in other historical periods or places. There were three reasons for this: first, the highly fragmented political and confessional landscape created spaces for persecuted minorities, often coupled with rulers’ interests in profiting financially, economically, and politically from their admission (thus, for example, the brain drain occasioned by the Huguenot exodus benefited the host societies while weakening an otherwise dominant France). Second, there was a peculiar mixture in early modern Europe’s treatment of religious dissidents: on the one hand, they were considered dangerous threats to a society’s religious ‘purity’—which led to regular persecutions and expulsions. On the other hand, religious dissidents were partially tolerated for economic and political reasons, allowing persecuted minorities to settle elsewhere. Third, late medieval spirituality and the intellectual quest for the ‘true’ interpretation of the Bible, fully unleashed by Luther’s Reformation, engendered an unprecedented degree of religious pluralisation both within Christianity and Judaism, with each confessional variety claiming to offer the one and only way to salvation. In this way, religion in a very specific (sub-)denominational form was, and remained well into the eighteenth century, the mainstay of people’s daily aspirations. As a consequence, a specific creed was also a sufficient motive to leave everything—sometimes even including one’s family—behind and to risk one’s life in a foreign and potentially hostile environment, where this creed would become even more important as the core of one’s identity.

In addition to this common background, early modern religious diasporas shared a number of particular features. Their members often developed innovative economic skills and were commercially very successful; they displayed high levels of moral and work-related discipline, as well as high degrees of literacy and education (notably, including women); they were generally more egalitarian than the surrounding majority societies. Finally, undergirding their economic success, they maintained strong networks with diaspora groups of the same creed. All of these characteristics were present in (otherwise very diverse) Jewish communities, Calvinist and other ‘radical’ Protestant diasporas, as well as in Orthodox ‘Old Believer’ communities in Russia. The fact that these features were shared by groups with completely different religious convictions and practices suggests that they did not flow from any specific theology as suggested, among others, by the German sociologist Max Weber (1864–1920) in his Protestant Ethic Thesis, according to which the uncertainty of salvation in Protestant dogma drove many communities to embrace values of hard work, asceticism, and profitability. Rather, these features often stemmed from their specific ‘diasporic’ situation: a precarious existence, that is, within a foreign and often hostile society, usually coupled with harsh financial conditions, forced diaspora communities to organise themselves efficiently, to fully exploit their members’ potential, to develop new economic skills, and to maintain bonds with coreligionists farther afield.

The Iberian Peninsula: Crossroads of Religious Migrations and Expulsions

In Portugal, after the massive influx of Sephardic Jews from Spain and the forced conversion of all Portuguese Jews in 1497, these so-called ‘New Christians’ lived relatively quietly until 1536, when the Portuguese Inquisition was established. In the second half of the sixteenth century, many New Christians, who were accused of being crypto-Jewish (i.e. practising Judaism in secret while outwardly presenting themselves as Christians), fled to Spain. Their subsequent persecution, both in Spain and Portugal, created a major diaspora in Europe and the New World, generating among the converts a feeling of belonging to ‘the nation’ (meaning the Sephardic diaspora). Thus, from the beginning of the Atlantic expansion, New Christian families served to populate the overseas Iberian empires (as early as the end of the fifteenth century, Jewish children had been sent to populate the African island of São Tomé). They also underpinned the creation of Atlantic networks that allowed them to take advantage of commercial opportunities opened up by Iberian overseas expansion. Although New Christians and Jews were formally prohibited from emigrating to the Portuguese and Spanish Americas, the Crown implemented formulae which made it easier for them to emigrate or find other ways to escape these restrictions. Consequently, New Christians, a great majority of them of Portuguese origin, established themselves in the Caribbean, Mexico, Brazil, and Peru, where they played an important role in businesses such as sugar plantations, the slave trade or mining. In these places, some of them continued practicing Judaism, while others married into Catholic families.

Another important Iberian diaspora is that of the Moriscos. These descendants of the Muslim al-Andalus settlers were forced to convert to Christianity in 1492 as a result of the so-called Reconquista, the ‘reconquest’ of the Iberian Peninsula by Christian kings. In terms of numbers and their significance, the expulsion of this group from the Iberian Peninsula and the resulting diaspora are of great importance. Very numerous in Valencia and Aragon, but also in Castile and Andalusia, the Moriscos were a highly heterogeneous group, whose relationship with the old Christians was complex and not easily reducible to a binary opposition. However, between the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, the Moriscos suffered a double expulsion. After the so-called Rebellion of Granada (1569–1571), they were forced to leave the Kingdom of Granada to be exiled to the territories of western Andalusia and Castile. Then, due to fears that the Moriscos were conspiring with the Ottomans against the King of Spain and his Christian subjects, but mostly for political reasons, King Philip III (r. 1598–1621) ordered their definitive expulsion in 1609: about 300,000 Moriscos were forced to leave their lands and workshops. While those who wanted to take their children under the age of seven were forced to go to Christian countries, disembarking in Marseille and Livorno, the majority went to North Africa (Morocco, Algiers and Tunisia) where local rulers like Uthman Dey of Tunisia were eager for the trades, techniques, and knowledge which the Moriscos brought with them, and to the eastern Mediterranean, mainly to Istanbul. The transition was not always smooth, even for those who, as Muslims, shared the faith of their new host societies; but while many were subject to further exclusion, abuse, and assault, most were eventually absorbed into the local societies.

Migration and War: Christian Europe and the Ottoman Empire

As we have seen, migration in the early modern period often originated in the displacement of the adherents of particular creeds, as a result of the repressive and exclusionist religious policies of European rulers, as well as the efforts of majority communities to rid themselves of the presence of religious minorities in their midst. Another major cause for migration in the early modern period was military conflict. This is particularly true for multi-ethnic East-Central and South-Eastern Europe. In these regions, the expansion (and later withdrawal) of the Ottoman Empire led to large-scale processes of migration which were continuous from the sixteenth century to the mid-eighteenth century, even if they varied considerably in terms of intensity, direction, and type over the course of the period.

The Ottoman army’s move westward on the European continent, where it had controlled territory since the fourteenth century, created large numbers of refugees. Moldavian Romanians and different Cossack and Tartar tribes displaced by Ottoman expansion settled in the eastern border regions of Poland, while the southern parts of Hungary had already become a new home for a mainly Orthodox Serb population at the turn of the fifteenth century. This first wave of refugees was partly absorbed by the border defence establishments and partly by the lands of the nobles. In parallel, ethnic Turks migrated westward, especially into the Balkans, as colonists from Anatolia followed the Ottoman armies—sometimes voluntarily, sometimes as a result of forced resettlement programmes—with the aim of consolidating Ottoman rule over the recently conquered territories. As the expansion moved closer to central Europe, and especially after the occupation of Belgrade (1521) and Buda (1541), an ever-growing number of Balkan people also settled in the lands conquered from the Kingdom of Hungary. In fact, the people serving in Ottoman border fortresses were mostly Bosniaks, Serbs, and Albanians who had recently converted to Islam as well as Serbs, Vlachs, and Croats who remained Christians.

On the whole, the more affluent among the Hungarian, Croatian and German population of these regions left the territories conquered by the Ottomans. The burghers, who—for the most part—were ethnic Germans, were received by Vienna and the northern Hungarian royal free cities because of their previous trade relations. Some of the Croatians settled in eastern Austria, where they played an important part in the protection of its borders, while the others, along with the Hungarian nobility, moved to the northern part of Hungary, which came under Habsburg rule after the death of King Louis II (r. 1516–1526) in the Battle of Mohács (1526). The inhabitants of the market towns and villages, however, largely remained. While earlier generations of historians had assumed that they migrated on a large scale, it has been shown that they only left temporarily, fleeing into the surrounding woods and swamps to escape the devastation of war or tax collectors, later returning to their homes to continue farming or to market towns where safer and more favourable economic conditions could be negotiated with the Ottoman rulers.

The greatest migration flows in East-Central and South-Eastern Europe were caused by the great wars, such as the so-called Long War (1593–1606), and the conquest of Hungary by the Habsburgs at the end of the seventeenth century. In these instances, we cannot talk about refugee populations, but about population exchange—as the more or less complete depopulation of rich agricultural areas and river valleys was followed by immigration from poorer peripheral regions. As a result, Slovaks and Russians moved farther south and Croats, Serbs (who had already established major colonies north of Buda), and Romanians arrived in great numbers. At the same time, both central government and local landlords implemented settlement policies—culminating in the first half of the eighteenth century, when Emperor Charles VI, at enormous expense, brought nearly 400,000 settlers to Hungary, most of them from South Germany. As they were settled en bloc in largely depopulated areas, this migration caused significant ethnic changes.

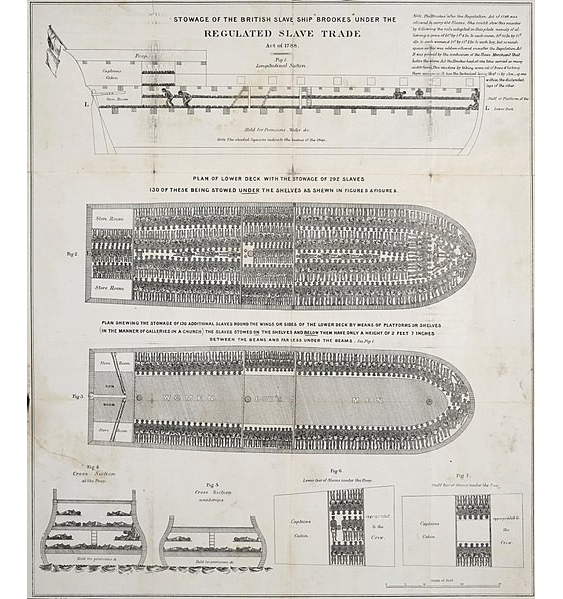

Fig. 1: Stowage of the British slave ship Brookes under the Regulated Slave Trade Act of 1788, Public Domain, Wikimedia, Ras67, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Slaveshipposter.jpg. Images like this one have become iconic representations of the inhumanity of the Atlantic slave trade.

The military conflicts with the Ottoman Empire, as well as with various North African rulers and the Crimean Tatars, also led to a steady stream of slaves from Europe to North Africa and the Middle East, and vice versa. This phenomenon, to be sure, was on a categorically different scale from the Atlantic slave trade (discussed below), both quantitatively and qualitatively. Although it is difficult to gauge the number of people affected, a recent estimate suggests that roughly 35,000 enslaved Europeans lived in North Africa at any one point in the seventeenth century. The number of Muslims held in captivity in Europe appear to have been significantly lower: since Ottoman forces tended to be more successful on the battlefield, they took more captives. The phenomenon is well-attested, not least in countless captivity narratives written by Italians, Spaniards, Dutch-, French-, and Englishmen who were taken captive by the ‘Barbary’ pirates operating out of ports such as Algiers, Salé (in modern-day Morocco), Tripoli, and Tunis, attacking ships and raiding coastal settlements. Taking slaves was part of their business, but the point of that business was largely to extort high ransoms in exchange for their safe return. At the same time, many slaves were also released into freedom following their religious conversion and integration into the host society. As a consequence, for many European slaves as well as many Muslim slaves in Europe, slavery was not permanent. In fact, well-known figures such as the Spanish writer Miguel de Cervantes (1547–1616), the author of Don Quixote, spent time as slaves in Algiers and elsewhere in the Ottoman Empire. Ironically, so did John Newton (1725–1807), a British captain of a vessel engaged in the Atlantic slave trade, who later became a clergyman.

Coerced and Forced Migration: Europe’s Global Footprint

If migration was not always voluntary, the nature and extent of force applied to different groups differed widely. Settlement programmes like those mentioned in the previous sections could offer incentives for those agreeing to move—alongside a wide variety of punishments for those who refused to comply—as with the expulsions of Jews and Moriscos from the Iberian Peninsula. Another type of coerced migration is the movement of those who exchanged their prison sentences in Europe for exile in overseas territories and—in so doing—played an important role in the formation of empires. For example, the Portuguese Empire in West Africa and the Indian Ocean (Estado da India) depended on prisoners who served as soldiers in its outposts. ‘Gypsies’ (Romani people) would also be transferred to the overseas territories. It is also worth mentioning the so-called Órfãs d’El-Rei—orphaned daughters and widows mostly of minor nobility who served the Portuguese Crown—especially in the case of the Estado da India. After spending some time in an orphanage in Lisbon, where the values and qualities considered appropriate for model females were instilled in them, they travelled to the overseas territories with a dowry that enabled them to marry there. This migration, while forced by circumstance, opened up interesting opportunities for these women and their families as a result of their marital unions. The so-called filles du roy, sent by Louis XIV to New France (Canada), played a similar role in helping to increase the number of inhabitants of European descent in the French American territories.

The migration of around one million indentured servants to the British colonies or to the Caribbean during the early modern period should also be considered here. Indentured servants were men or women who took out so-called ‘indentures’: loans to pay for the cost of their transportation overseas. In return, the labourers were obliged to work without salary for their employers for typically between four and seven years. Although they were not slaves, their living conditions were often not that different. Many indentured servants decided to migrate to escape from poverty or to look for new opportunities, but a significant number of them were deceived about the conditions they were going to find, forced to migrate for religious reasons, or as a punishment for having participated in rebellions or civil wars, while some were even kidnapped. This brings this type of migration closer to others in which coercion played a major role.

Europe and its colonies in the New World also played a key role, of course, in what is not only a particularly gruesome example of forced migration, but most likely the numerically largest global migration in the early modern period: the deportation of approximately 8.6 million enslaved Africans to the Americas between 1500 and 1800 (a relatively small number of about 11,000 Africans were also taken to Europe itself). Conditions aboard the vessels which carried them were so disastrous that almost one and a half million people lost their lives before reaching the Western shores of the Atlantic (see Figure 1). After Europeans had brought new diseases that killed large parts of the indigenous populations of the Americas, they established vast sugar plantations (primarily in Brazil and the Caribbean) in which enslaved Africans were worked to exhaustion and, more often than not, death. Europeans bought and transported these forced labourers to supply plantations with manpower—and it was also Europeans who consumed the sugar produced by slave labour. While by far the largest numbers of enslaved Africans were transported on Portuguese and British-owned ships, the slave trade was such big business that it drew in players from all over the European continent—if not as active participants, then at least as investors. Moreover, since slaves were not simply robbed but often bought from African traders, the trans-Atlantic slave trade provided a stimulus for export-oriented manufacturing in Europe itself as well as the European colonies in Asia. Despite rising political agitation against the slave trade and the enslavement of Africans from the late eighteenth century onwards, the trade continued until the mid-nineteenth century.

Conclusion

For Europeans, migration was common in the early modern period, as they migrated within the continent and to other parts of the world. They did so for a wide array of reasons, but usually they migrated in order to improve their situation, seeking safety and economic opportunities. However, migration was not always voluntary. Repressive policies prompted religious minorities—members of various Christian groups, Jews, and Muslims—to settle elsewhere. Displacement caused by religious policies, as well as displacement caused by warfare, had wide-ranging implications for economic, cultural, and intellectual life in the migrants’ new homes, as well as the places they left behind. Migration was also stimulated by early modern authorities’ deliberate settlement programmes, which they undertook in order to repopulate war-torn landscapes, increase their hold on newly conquered territories, or attract particular talent. Europe’s contact with the wider world following the voyages of ‘discovery’ in the fifteenth century created new opportunities and destinations for migration, providing a way out for those who had few opportunities, or substituting exile in the colonies for punishment at home. The continued practice of slavery, finally, resulted in the large-scale deportation of people, especially from Africa, across the Atlantic to Europe’s new American colonies. This latter movement was predicated on the migration of Europeans to the New World, a movement which had profound effects not only on the populations, economies, political conditions, and cultures of Europe itself, but also those of Africa and the Americas.

Discussion questions

- This chapter shows that migration was a common experience in early modern Europe. Describe how this experience differed in different parts of Europe, e.g. Eastern Europe and the Iberian Peninsula.

- What role did religion play in early modern migrations?

- Think about similarities and differences with Europe today: how has this experience changed or remained the same?

- How has migration shaped Europe’s engagement with the rest of the world in the early modern period?

Suggested reading

Bade, Klaus J., Pieter C. Emmer, Leo Lucassen and Jochen Oltmer, eds, The Encyclopedia of European Migration and Minorities: From the Seventeenth Century to the Present (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011).

Garcı́a-Arenal, Mercedes and Gerard Wiegers, eds, The Expulsion of the Moriscos from Spain: A Mediterranean Diaspora (Leiden and Boston: Brill, 2014).

Israel, Jonathan I., European Jewry in the Age of Mercantilism (1550–1750) (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1985).

Klein, Herbert S., The Atlantic Slave Trade (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012).

Terpstra, Nicholas, Religious Refugees in the Early Modern World: An Alternative History of the Reformation (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2015).