6.3.2 Centres and Peripheries in Modern History (ca. 1800–1900)

© 2023 Halmos, Kindler, Marin, and Martykánová, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0323.71

Introduction

In Jules Verne’s novel Around the World in 80 Days (1872), the protagonist Phileas Fogg discovers in the Morning Chronicle of 2 October 1872 that it is now possible to circumnavigate the globe in eighty days from east to west, on a route that alternates between railways and steamships. In its own way, Verne’s novel recounted the odyssey of the contemporary world, which his hero, obviously British and a maniac of time, would not have been able to achieve without the immeasurable progress made in land and sea transport. Similarly, new means of transatlantic communication had extended land-based telegraph networks.

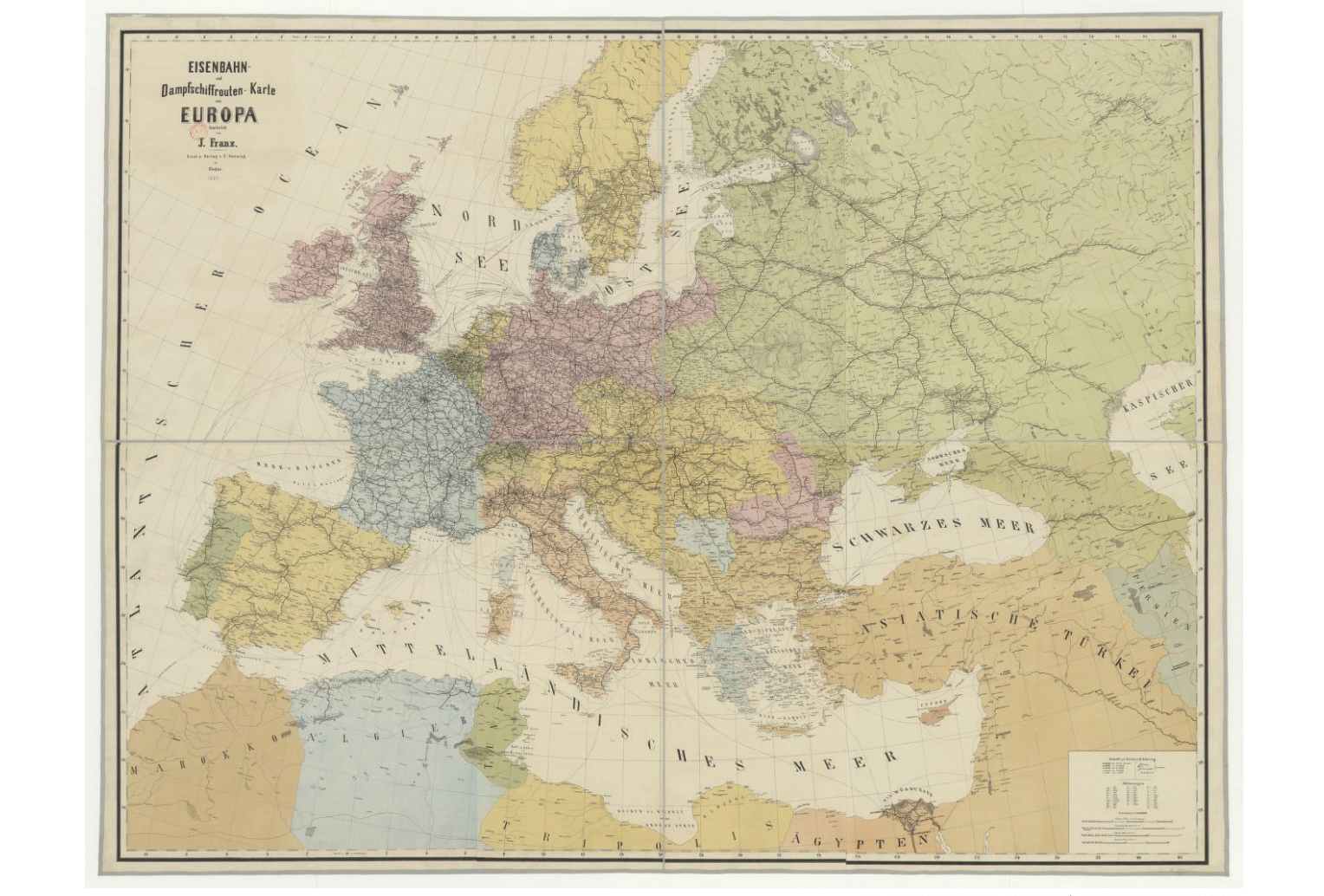

The “long nineteenth century” (Eric Hobsbawm) was the century of the steam engine. Due to its amazing power, the exchange of people, goods, and ideas reached new dimensions. Installed in locomotives, the mobile steam engine became the driving force of an ever-faster journey to modernity. Railways were regarded as symbols of progress, transporting products and, so it was thought, values to the remotest peripheries and regions. Most importantly, railroads were able to transcend the obstacles of space, distance, and time. Taken together, they seemed to be a solution to one of the crucial questions of European history, beginning from the mid-nineteenth century: the integration of internal and external peripheries and their connection to economic and political centres. This chapter uses railroads and their infrastructures as a lens to discuss this decisive and ambivalent process that has shaped European history to this very day.

Empirical evidence used in this chapter stems largely from three major empires that were themselves located at the European peripheries. They—the Habsburg Empire, the Russian Empire and the Ottoman Empire—were only partially ‘European’ in some eyes. As examples, they highlight the significance of ‘peripheral’ regions for larger developments in European history and at the same time they provide important insights into the contingent nature of centre-periphery relations.

Fig. 1: J. Franz, Map of Railway and Steamship Routes in Europe (1883), Bibliothèque nationale de France, https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b532394204.

The Steam Revolution and the New European Geography

The geography of transport in pre-railway Europe was highly diversified, depending on three factors: natural conditions, centuries-old legacies, and the extent of the investment efforts made during the Enlightenment and the first part of the nineteenth century to develop a coherent system of trade. The continental states did not wait for the railway to implement a proactive policy of transport infrastructure development. Indeed, faced with the British challenge, the continental countries were in no doubt that Britain’s advance was due to the quality of its communications network.

The improvement of infrastructure allowed a complete transformation of transport modes. The first half of the nineteenth century witnessed a veritable revolution on the roads in the whole of Western Europe. France, Great Britain, Prussia, the Netherlands, Belgium, Northern Italy, and Switzerland went through major changes, thanks to improvements in materials, vehicle design, and energy management, due to improved horse breeding. Thus, the number of kilometres covered without stopping by stagecoaches increased from about nine kilometres in 1780 to twenty-two kilometres in 1850. In this respect, the travel revolution preceded the railway. The same dynamic can be observed for canals. Canals play a decisive role in the history of European transport. Many had been built over many centuries, but the nineteenth century marked a change of scale. Thus, well before the railway revolution, the land transport revolution already accentuated the differentiation of the European space. Hence, in the case of France around 1840, we can counterpose a northern France equipped with a dense network of canals and roads, to a southern and western France still unequally served. Similar contrasts can be observed in Italy and Germany.

From the 1810s onwards, on the Thames and on the Rhine, steamships became the norm. The decisive progress was based less on the increase in speed than on the phenomenal increase in carrying capacity. This revolution in transport made it possible to envisage the crossing of seas and oceans in a different way; this boom in maritime transport led to a considerable growth in port cities, brutally accelerating the phenomenon of global coastalisation.

Steam was also the cause of an upheaval in the means of land transport. Railways had existed since the late eighteenth century: in the mining countries of Western Europe, wagons on rails pulled by animals were used to move the ore. But the advent of steam traction changed everything. The first trials took place in the 1820s and the first general traffic line was opened in 1830 between Manchester and Liverpool. The British origin of the phenomenon led to the imposition of the standard gauge of 1.42 metres almost everywhere—the standard to which the first locomotives exported by Britain were built. The railway made it possible to move heavy loads of people and goods without having to deal with the geography of water. It thus became possible to deeply reshape the geography of the European continent. The availability of transport infrastructure had already been of great importance to Britain even before the nineteenth century: for several centuries the expansion of the British Empire’s boundaries had taken place owing to a powerful navy and the domination of global trade routes, with trading outposts gradually turning from informal to formal empire. The arrival of the railways in the nineteenth century gave imperial Britain several advantages: more immediate access to raw materials and markets as well as the faster movement of troops and effective repression to imperial hotspots. In the process, former backwaters such as the Midlands and the northern reaches of England were transformed into booming industrial centres, while far-flung colonies such as India received railways and a modern infrastructure.

Although the first commercial railway line was opened in 1812, the widespread use of trains for transport grew very gradually. The establishment of the railways can be understood as a response to three different requirements. Railways were a response to the demand for transport in countries or regions that were already well served by roads and canals, but where there was strong traffic pressure on infrastructure. This was the case in north-western Europe, where the first railway systems were built from the 1830s and 1840s.

Especially from the 1850s onwards, trains were to serve as a deliberate solution to the problem of economic backwardness—as a response to the backwardness of the land transport system and the economy in general. This was the case in Spain, Russia, southern Italy, and western France. Finally, in the third case, the train was perceived as a means of establishing a system of long-distance exchanges that would enable the national space to be structured and integrated into a larger European space. This was the Portuguese project, but also that of Belgium and the Netherlands. State control of the railways was a guarantee of national independence and allowed the unification of the territory. More generally, whether in France, Germany, Switzerland, or Italy, the debates on railway routes revealed the dual ambition of achieving national unity and opening the country to trade.

This hierarchy of places and spaces was transformed rapidly by the mobile steam engine. The movement of goods increased dramatically thanks to this transport revolution. Between 1840 and 1870, freight costs fell by seventy percent in international trade. This triggered a process of specialisation in the different regions of Europe between agricultural, mining, or industrial activities. A more structured geographical landscape was created, partly embedded in old spatial patterns. The most industrialised and urbanised zone extended from the centre of England to the north of the Italian Peninsula, passing through the Rhine and Rhone regions, accompanied by a few more distant industrial districts, for example in the Iberian Peninsula. This concentration was redoubled by the means of transport: maps of the expansion of the railways outline this area of greater density. As the railway played an important role in the strengthening of central districts and regions, it also, conversely, doomed others to decline. Many once-prospering cities or whole regions faced deprivation when they were cut off from railway infrastructures and the economic opportunities they provided. These new infrastructures could leverage the creation of national markets. And what was more, railways fostered internal and transnational migration on a whole new scale. In search of opportunities people departed agricultural regions for industrial cities, as well as mining and metallurgical regions.

The steam revolution of the nineteenth century did not only transform mainland Europe, but it changed its relation to other parts of the world. Its acceleration of the reconfiguration of European peripheries thus also occurred on a global scale. The year 1869 proved to be crucial in this regard. The Suez Canal was opened, significantly reducing time and costs for global trade. In the same year, the Transcontinental Railway started operating in the United States, not only connecting northern America, but also serving as a shortcut for the journey from Russia’s Far Eastern regions to its capital, St Petersburg. In this process, easier and cheaper communication allowed investment possibilities to proliferate, while quick access to information set profit expectations higher.

Trains and the Reorganisation of European Peripheries

But how did this ‘success story’ look from Europe’s (imperial) peripheries? The history of the railway networks in the three ‘peripheral’ empires show a very different history from that of Western Europe. Hungary, part of the Habsburg Empire in the nineteenth century, did not have an advantageous transportation infrastructure. Like most other parts of the Habsburg Empire, it was landlocked. On the eve of the nineteenth century it was only the wars of the First French Republic that gave Hungary a chance to sell its grain surpluses. Western urbanisation impressed that there was a demand for grain. Water regulation—partly regulating waterways but also reclaiming arable land—was a new aspiration for Hungarian landowners. Railways were built to connect the large plains of the country to commodity markets. Both developments demanded capital imports and internal accumulation. Not too long after the middle of the nineteenth century, the world’s largest capacity for steam milling emerged in the commercial capital of the country, the city of Pest. Yet declining transportation costs had made US grain so cheap in Europe that Hungarian exports could not compete outside the borders of the Habsburg Empire. Agriculture could not develop as the country’s reformers had imagined. At the same time, news about the rising demand for labour in the US spread rapidly all over the country and, at the turn of the century, migration to the other side of the Atlantic grew.

The Russian experience was different—at least partly. When the Russian Empire entered the railway age in the middle of the nineteenth century, the tracks were a representation of imperial pride and power. A first line (opened in 1837) operated only between the capital St Petersburg and the Tsarist residence of Tsarskoye Selo—connecting only the very centres of political power. Things changed with the construction of the Moscow-St Petersburg line, which opened in 1851. This ambitious project was widely regarded as a major step to overcoming Russia’s “illness of space”, as the historian Roland Cvetkovski has called it, and to territorialise the empire. Advocates of the empire’s speedy ‘railroadification’ pointed not only to its political benefits, but also to its economic advantages. Trade would flourish between Russia’s remote and isolated regions and its centre. And more than that, the railway was intended to bring ‘civilisation’ to the ‘backward’ populations of the Russian peripheries. Planners and bureaucrats alike imagined the integration of empire as a process wherein ideas and normative orders travelled from the centres to the peripheries with goods and raw materials sent back to feed the economy and strengthen the state. The railroad was thought to transport Russia and its multi-ethnic population into modernity.

From modest beginnings, the Russian rail network grew with impressive speed over the next decades. At the end of the nineteenth century, it connected not only the empire’s European regions but reached its Central Asian and Far Eastern peripheries. The network was a representation of state power—its lines connecting the metropolis with its peripheries—but it did not provide connections between regions. The Russian railroad network was thus a means of imperial integration and international separation at the same time. Although it was connected to Europe via rail, the Russian Empire used a different gauge than its neighbours.

The construction of the Trans-Siberian Railway between 1891 and 1916 was testament to Russia’s urge to integrate its peripheries on the tracks. Even before its final completion the effects of the Trans-Siberian Railway, connecting Moscow with Vladivostok at the shores of the Pacific, were clearly discernible: the railroad enabled the resettlement of peasants from the European parts of the empire to Siberia and the Far East. It also served as an important means for Russian grain exports. Towns and cities along the line were booming. The Trans-Siberian was also strategically important, located dangerously close to the Chinese border—during the Russo-Japanese War of 1904–1905, its limited capacities caused severe logistical problems for the Russian Army.

The expansion of the railroad network had several unintended consequences. At first, the lines and networks did not always follow long-established trade routes. Many towns and regions that were not connected to the railway system faced economic decline and lost their former political significance. In other words, where some peripheries grew closer to centres and became less ‘peripheral’, new peripheries emerged at the same time. Secondly, whereas the railroad and its infrastructures were definitely modern, its impact on societies at the periphery were not always modernising in the sense tsarist elites had hoped for. In many cases, peasants and local elites opposed the construction of new lines or applied their own agency and practices when using them.

Thirdly, the railway contributed not only to the expansion of the centre’s power over peripheries, but it also induced change and dynamism in the imperial centres themselves. Around 1900, many observers from the Russian urban elite regarded train stations in major Russian cities as places of disorder and chaos. They were crowded with people from all over the empire who flocked to the booming cities, searching for work and modest prosperity. The newcomers carried, along with their few belongings, the cultural values of the peripheries to the centres; a single train journey to the city was not enough to transform them into ‘enlightened’ citizens. In their new role as workers, people from the inner and outer peripheries would soon play a major role in the revolutionary chaos that was about to unfold in the empire. The railway had helped many of them come into position and it was no coincidence that some of the most important episodes of the Russian Civil War were fought along the railway lines. No longer did rail simply connect centres and peripheries, it now represented the very arteries of political power in a disintegrating empire.

The third case is quite different. In its heyday, the Ottoman Empire was the centre of its own world, and all that lay beyond its frontiers was, in a sense, periphery in the eyes of its ruling elites. As for the Ottoman domains themselves, it is tricky to apply the notions of centre and periphery to an empire that was, like many patrimonial empires of that time, based on diversity. This was not only in terms of language, ethnicity, and religion, but also in terms of law, regulation, and the management of different territories. The nineteenth century, with its state-building process, its notion of equality before the law and its standardisation of government intervention, necessarily meant an important change for the Ottomans. Until the early years of the twentieth century, the imperial elites considered their domains in the Balkans, together with western and central Anatolia, as the core lands of the empire. In fact, many of them were born and raised in these regions. A nineteenth-century gentleman from Istanbul understood Libya or Iraq as imperial peripheries—but not the Balkan regions, even if they had acquired a high level of autonomy (Wallachia, for example, but not Thessaloniki or Skopje). In fact, some historians have understood the intervention of the Ottoman government in some of the Arab territories, including the investment in infrastructures, as internal colonisation, legitimised as a sort of civilising mission. Such self-fashioning as the moderniser of ‘backward’ regions can be understood, partly, as a response to European stereotypes of the Ottoman government as inefficient and a hindrance to the progress of its subjects. In some cases, Ottoman investment in infrastructures in remote territories had a clear political message: the Hejaz Railway, built and funded by the Ottoman government, was to take pilgrims safely and efficiently to Medina, while emphasising the sultan’s role as protector of the Holy Shrines and the leader of the Muslim world.

In the Balkans, the interplay of forces around infrastructure was extremely complex, particularly in the case of railways. The actors involved had different, often clashing, interests. The Ottoman authorities were willing to fund infrastructures to boost the economy, particularly promoting the commercialisation of agricultural products. However, like any nineteenth-century government, they also strove to use modern infrastructure to foster their control of the territory in both military and administrative terms. Local elites shared with the Ottoman authorities an interest in boosting local economies, but often had their own political agenda, such as promoting their region’s autonomy, independence, or even future territorial expansion to neighbouring lands. Foreign investors and railway companies also extracted profits while acting as agents of foreign countries and their geopolitical interests. Concerning infrastructures, the Ottoman and post-Ottoman Balkans became, in the second half of the nineteenth century and the early twentieth century, a true European periphery. Politicians and investors from the wealthy and mighty European centres were able to draw and build the main lines of the railways in the region, while local actors, including the Ottoman government, were able to set their priorities and benefit from roads, ports and a few minor railway lines.

Conclusion

Throughout the nineteenth century, the steam engine reshaped the geography of Europe. The construction of new railway lines brought entire regions out of marginality, or allowed for better integration into increasingly connected markets. This new European geography was not only technological or economic, however. The same process of intensification of exchange can be observed in the cultural sphere, with the same scale effects. To give one example: in the case of theatre, the city of Madrid seemed to lag behind the great cultural capitals of the century, such as Paris, London, and Vienna. As the capital of a country with a fragile central state and delayed entry into industrialisation, Madrid was on the cultural periphery of Europe. However, seen from the perspective of the Hispanic cultural empire, the capital of Spain was the source of many theatrical and musical productions exported to its own Latin American peripheries.

Discussion questions

- In which ways did the transport revolution of the nineteenth century (trains, steamships, etc.) change international political relations in Europe?

- In which ways was this experience different between Western and Eastern Europe?

- Nineteenth-century Europe was dominated by several empires. How did the transport revolution change these empires?

Suggested reading

Alvarez-Palau, Eduard J., Alfonso Díez-Minguela and Jordi Martí-Henneberg, ‘Railroad Integration and Uneven Development on the European Periphery, 1870–1910’, Social Science History 45:2 (2021), 261–289, https://doi.org/10.1017/ssh.2021.1.

Caron, François, ‘Introduction: l’évolution des transports terrestres en Europe (vers 1800-vers 1940)’, Histoire, économie et société 11:1, Les transports terrestres en Europe Continentale (XIXe-XXe siècles), ed. by Michèle Merger (Paris : CDU Sedes, 1992) pp. 5–11, https://doi.org/10.3406/hes.1992.1619.

Martí-Henneberg, Jordi, ‘The influence of the railway network on territorial integration in Europe (1870–1950)’, Journal of Transport Geography 62 (2017), 160–171, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2017.05.015.

Otte, Thomas G. and Keith Neilson, eds, Railways and International Politics: Paths of Empire, 1848–1945 (Oxford: Routledge, 2012).

Rosenberg, Emily S., ed., A World Connecting: 1870–1945 (Cambridge, MA: Belknap, 2012).

Schenk, Frithjof B., Russlands Fahrt in die Moderne: Mobilität und sozialer Raum im Eisenbahnzeitalter (Stuttgart: Steiner, 2014).

Stanev, Kaloyan, Eduard J. Alvarez-Palau and Jordi Martí-Henneberg, ‘Railway Development and the Economic and Political Integration of the Balkans, c. 1850–2000’, Europe-Asia Studies 69:10 (2017), 1601–1625, https://doi.org/10.1080/09668136.2017.1401592.