7.1.3 Experiments and Avant-Gardes in Contemporary History (1900–2000)

© 2023 Bière, Gyimesi, Kornetis, and Schouten, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0323.78

Introduction

The meaning of the term avant-garde as we use it today—referring to cutting-edge, experimental, or radical works and people—is an invention of the twentieth century. Historically, it expressed an often dynamic blurring of the distinctions between art and politics and art and life after the destruction of the First World War: the new art movements of the early twentieth century, such as Dada or the Suprematists, not only aimed at revolutionising painting and architecture, but wanted to create a new, utopian world. In contrast to the traditional image of the artist as a genius-like figure remote from society, these avant-garde groups were politically engaged, and some were even actively involved in political revolutions. They put new ways of living—such as communes—to the test, and used new materials, such as everyday consumer items, in their art. The Second World War put an end to most of these artistic and political experiments, but they provided much inspiration to the flowering counterculture and art movements of the 1960s. Today, these experiments continue to inspire artists and societies to pay attention to values such as being different, open-minded, and experimental in works of art and in society at large.

The Idea of the Avant-Garde

The twentieth century gave expression to a whole set of socio-cultural and political experiments in which the artistic and literary avant-garde played a pivotal role. The term ‘avant-garde’ originates from French military language, referring—in that context—to a small group of soldiers who scout out or explore an area in order to get information about the enemy. However, it was the Bolshevik revolutionary leader Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov, alias Lenin (1870–1924), who explicitly attributed a political role to the ‘avant-gardist’ at the beginning of the twentieth century. By that time, the term was particularly linked to the arts, due to a notion that art, more than any other domain, most challenged mainstream ideas and values. Artist and art critic Alexandre Benois (1870–1960) was the first to use the term in art criticism in a negative way to describe the works of some young artists who had rejected the idea of beauty (1910). The artists of the beginning of the twentieth century that we consider ‘avant-garde’ today did not always use this word, however, and they never used it to label themselves. It only became an accepted term in art history in the 1960s.

The background for these artistic developments was the incredibly turbulent era around the turn of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, a period marked by new inventions, innovations, explorations, developments by scientists, engineers, researchers, and travellers. The results of these changes became widely known among ordinary people and had a deep impact on their thought as well as their day-to-day lives. Science became a reference point for artistic life and vice versa, as intuition in research (an ability traditionally attributed to artists) became more appreciated as a guide for formulating new professional goals. Many Russian avant-garde artists, such as Kazimir Malevich, Wassily Kandinsky, Mikhail Larionov, and Pavel Filonov, believed that the process of creating art was similar to a series of experiments in physics or chemistry and equal to them as a relevant way of acquiring knowledge about the world at large. Still, avant-garde artists were not uncritical of the growing impact of science in life, and many lamented its ‘rational’ and materialistic dimension. Most famously, Kandinsky argued in 1910 for an art that would not rely on the material world, but rather on the expression of the artists’ inner selves, an idea that strongly impacted avant-gardist circles and that, arguably, can also be regarded as one of the core ideas behind avant-garde art.

Another important feature of the avant-garde concept was an eagerness to eliminate borders between creating art and living. The new ideal was the inventor-engineer-artist whose works merged art and the everyday life of the masses. Artists also wanted to participate in the production processes of the world of which they were a part, and functionality was interpreted as an aesthetic category. Industrial design became a matter for artists. Vladimir Tatlin’s famous “Monument to the Third International” (1919–1920) was an impressive representation of the way in which the symbolic meaning of the construction of an object became crucial—even though it was never actually built. An interesting experiment of living á l’avant-garde was carried out by the group UNOVIS in the Belarusian city of Vitebsk in 1919–1921: the artists transformed the city centre into an open-air museum of Suprematism, with members wearing ‘Suprematist’ clothes designed by themselves, and remaking the interior of their school with furniture designed according to the Suprematist principles. In the Soviet Union, during the 1920s and 1930s, several house-communes were built following the aesthetic programme of constructivism and according to certain conceptions of egalitarianism, collectivism, and progressivism. At the same time, and in alignment with the above-mentioned ideas of Kandinsky on the spiritual in art, avant-garde artists, such as the German Expressionists, tried to influence and ‘awaken’ the world through the expression of their inner, spiritual visions on canvas and paper—which was another way to eliminate the ‘borders’ between art and living.

Fig. 1: Vladimir Tatlin and an assistant in front of the model for the Third International (November 1920), Public Domain, Wikimedia, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Tatlin%27s_Tower_maket_1919_year.jpg.

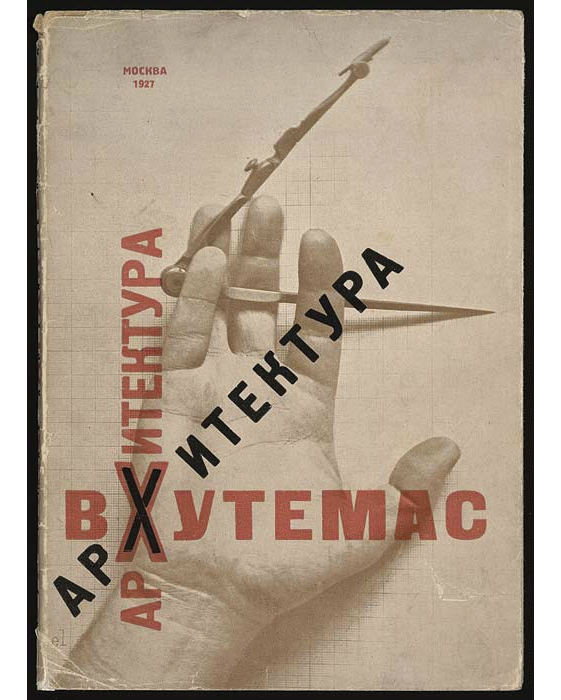

Representatives of the so-called historical avant-garde (i.e., the first generation of avant-garde artists in the 1900–1920s) were convinced that the new arts were meant to literally build a new life with the potential of ‘realising the future’ here and now—that is, new artistic ideas and methods were treated as guidelines for future life in a broad but very concrete sense. This concept was manifested in the clearest way in the artistic and architectural movements of constructivism, represented, for example, by the German Bauhaus school and the Russian state art and technical university called VKHUTEMAS (Vysshiye Khudozhestvenno-Tekhnicheskiye Masterskiye).

Fig. 2: El Lissitzky, book cover for Architecture at Vkhutemas (1927), Public Domain, Wikimedia, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Vkhutemas.jpg.

Intrinsic to the avant-gardist wish to create and ‘renew’ for future life was a deconstructive approach based on an audacity for experimentation that was both technical and stylistic. The technique of montage (Cubist, Dada or Surrealist collages, Dada photomontages, etc.), based on a clash between forms, colours, textures, objects, images, and the integration of material objects into art (ready-made, assemblage, combine paintings) testify to the displacement of the image in art from the space of representation to that of presentation. The use of objects as material proposed a more participatory position for the spectator and radicalised the identification of the space of creation with that of daily, social, urban, and political life. New artistic practices (happenings, events, kinetic art, visual art, installations) and new materials and techniques (neon, television, video, laser) multiplied from the end of the 1950s onwards, while the beginning of that decade was marked by the triumph of the various currents of abstraction. The means of artistic expression cross-fertilised and multiplied throughout the century, renewing the ways of giving form to things and creating new ways for artists and audiences to ‘see’. This development continued until the progressive vision of art disappeared at the end of the seventies.

Art Means Politics

For the artistic avant-garde of the early twentieth century, creating art was a form of social and political activity. While in Western Europe the phenomenon of politically engaged artists was mostly represented by the work of outstanding individuals and small-scale artistic groups (for example Pablo Picasso, Salvador Dalí, Henri Matisse, Robert Delaunay, Lajos Kassák, the artists’ group Die Brücke, etc.), in the young Soviet Union avant-garde enterprises evolved large-scale social dimensions and fostered a completely new general system of art institutions based on avant-garde principles. In the field of higher education and academic research, the avant-garde took the form of a new network of museums and ‘culture houses’ throughout the Soviet Union, and institutions like the above-mentioned university, VKHUTEMAS, or INHUK, the Institute of Artistic Culture, carried out scientific research focused on the nature of colour, line, form, facture, and composition as basic components of the fine arts.

The ethos of the avant-garde in Europe was often focused against authoritarianism and—especially—against a bourgeois liberalism, making art a battlefield of ideas and experiments within and outside the confines of artistic discourse. Artists aligned themselves with political views which attacked bourgeois society from both the left and right of the political spectrum. In the 1920s, for example, the new Soviet regime gave space for the fulfilment of (left-wing) avant-garde artistic ambitions as part of their drive to transcend the old, Tsarist regime’s habits, fashions, views, and traditions—to open up new ways of doing things for the masses. However, the Soviet government’s attitude radically changed at the beginning of the 1930s, when Stalin proclaimed the programme of Socialist Realism for the arts, putting an end to the practice of artistic freedom. Manifesting individual views via individual artistic language—a process that was central to the avant-gardist ambition—became dangerous and could result in different forms of severe retribution, such as prohibition of one’s works being exhibited or published, loss of employment, being put on trial (see Kazimir Malevich), being sentenced to the Gulag, or even execution (as in the cases of the theatre artist Vsevolod Meyerhold and the poet Osip Mandelstam). A similar tendency towards repression occurred in the 1930s in Nazi Germany, with the application of the label ‘degenerate art’ (Entartete Kunst) to various avant-garde productions.

A rethinking and critique of the concept of modernity was a fundamental aspect of the relationship between art and politics during this period. While very much a ‘product’ of modernity themselves, the ideologically committed avant-gardists positioned themselves as harbingers of the destruction of ‘traditional’ experience. Faced with radical social and political transformations, new modes of industrial production and rationalisation, and a growing sense of psychosocial and intellectual-spiritual ‘alienation’ from the ‘modern’ world during the first half of the twentieth century, the avant-gardists explored new avenues in seeking to create, out of revolutionary activism and an experiential tabula rasa, a new art. In so doing, they opposed tradition with creative freedom, which was—to them—the only way to project the “new life” they sought to achieve and to bring their works into the real world. More than mere representation, art therefore became functional: what mattered was how the work functioned, not what it represented. Understanding themselves within a progressive vision of history, avant-garde artists sought to become both inspiration for and actors within a struggle to change objective conditions. Examples of such avant-gardes are the (already mentioned) French art movement of Cubism, the German Expressionist art group Der Blaue Reiter, the Russian Suprematist school, the Dutch group De Stijl, and the Russian art movement of Constructivism.

At the same time, they emphasised the value of the individual (artist) and his or her activity to oppose an ‘empty’ modern industrial world, the dehumanisation produced by technology; for them, art contributed to the recovery of creative energies outside the industrial (e.g. in the case of the Dada group and the cultural movement of Surrealism). In their view, art became intersubjective communication, a stimulus, to show people how to see and understand their world: in abstraction, painting ‘revealed’—they argued—what existed beneath the appearance of things. As Kandinsky and others believed, art had a spiritual function: it could provide, according to the Dutch painter Piet Mondrian, a de-individualised “new image of the world”. To discredit form as representation, Surrealism—inspired among others by Freud—also explored the territory of the unconscious as a means to go beyond the appearances of reality and to enter the realm of what it called “the marvellous” (e.g., the ultimate meaning of reality). In so doing, art became an adventure not only of the soul, but also of the mind. French-American artist and theoretician Marcel Duchamp freed artistic creation from the aesthetic criterion and refocused it on intellectual activity, and the conceptual artists of the 1960s would follow his example.

Faced with the evolution of sensibility in the modern era, the avant-gardes redefined the relationship between the internal and social function of the work of art and sought to fashion a new human out of the rubble of tradition. As a culture of utopia, the avant-garde wanted to return to the roots of artistic creation, while also paying greater attention to what was considered to be ‘primitive’. Throughout the twentieth century, the avant-garde looked to non-European arts, as well as to the popular arts in and outside Europe, in which it found forms and symbols that challenged Western aesthetic conventions: primitivism became a ‘mode of elaboration’, capable of generating particular creative processes and of accessing different modes of thought, such as the shamanism that fascinated the Surrealists or artists such as Joseph Beuys.

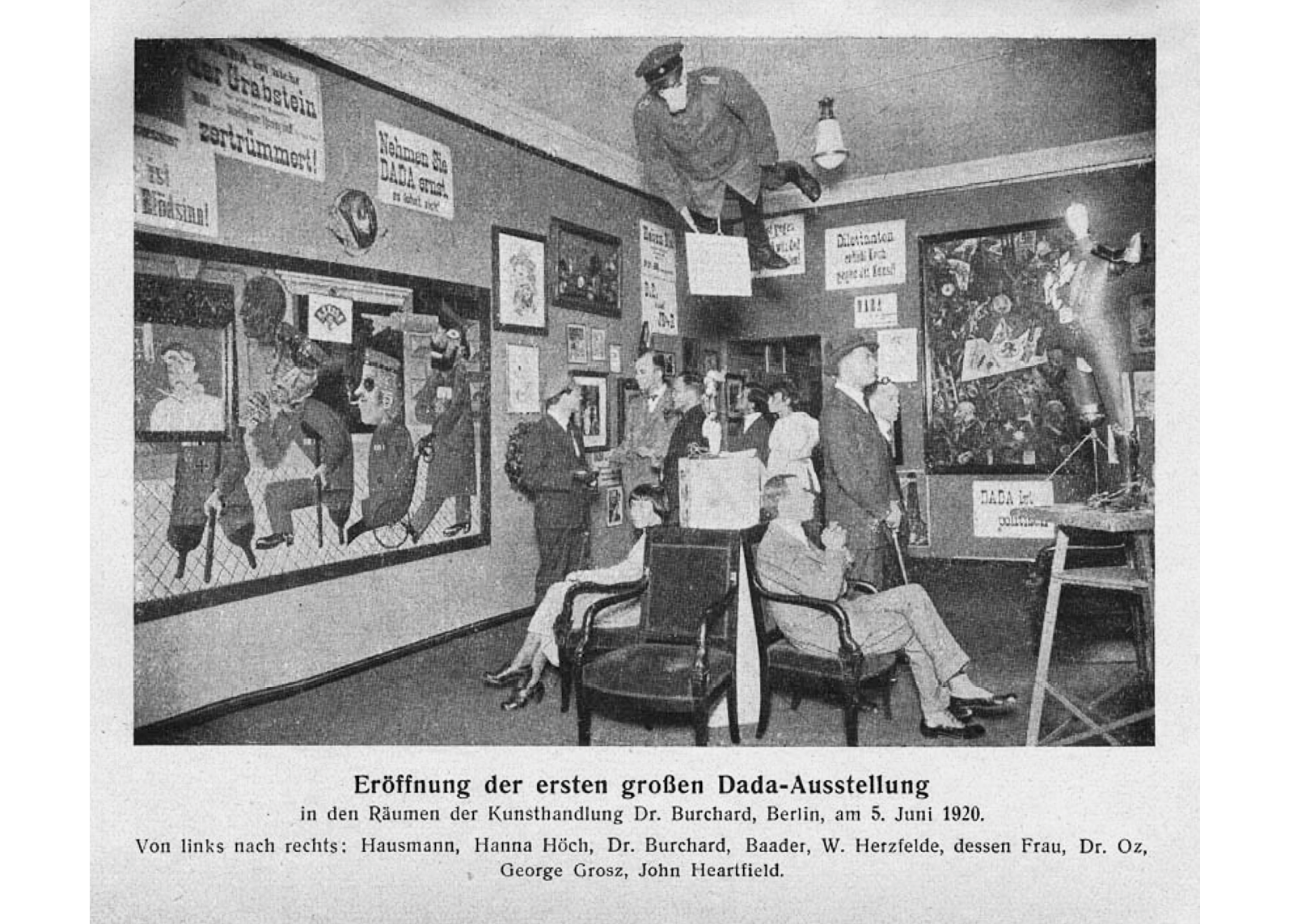

Fig. 3: Grand opening of the first Dada exhibition, Berlin, 5 June 1920. The central figure hanging from the ceiling was an effigy of a German officer with a pig’s head. From left to right: Raoul Hausmann, Hannah Höch (sitting), Otto Burchard, Johannes Baader, Wieland Herzfelde, Margarete Herzfelde, dr. Oz (Otto Schmalhausen), George Grosz and John Heartfield. Public Domain, Wikimedia, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Grand_opening_of_the_first_Dada_exhibition,_Berlin,_5_June_1920.jpg.

With the Dada movement in the late 1910s and early 1920s, the protest against conventional values had already been pushed to an extreme, to the point of denying all traditional values as well as art itself. Reducing art to pure action, as the avant-garde since Dada tried to do, also enabled avant-garde artists to demystify all values. Although there was no term to describe these attempts as ‘action art’ at the beginning of the twentieth century, the word ‘performance’ gradually came to be used in the 1960s. Performance art embodied the spirit of the avant-garde through its desire to ‘dissolve’ and ‘reformulate’ artistic categories.

New Waves: Neo-Avant-Garde and After

In the 1960s, a new wave of the avant-garde emerged in both Western and Eastern Europe, with less clear-cut political connotations, but still with a clear orientation to progressive principles and an oppositional attitude toward anything representing the mainstream.

The parallel movements of the ‘nouveau roman’ (‘new novel’) in literature and ‘nouveau réalisme’ (‘new realism’) in the arts in France are typical exponents of neo-avant-garde of the late 1950s and early 1960s. The main idea was to distance themselves from traditional writing and the arts. Conceptual art also followed suit with Fluxus, a loose group of neo-avant-gardist artists on both sides of the Atlantic from the mid-1960s on, trying to bypass the commercialised art world by putting their emphasis on thought processes and production modes as inherent parts of the artwork. Fluxus artworks often had a socio-political dimension and they were habitually left unfinished, making their sale or exhibition difficult. On the opposite side of the spectrum, pop art—especially Andy Warhol’s serialisations—came to symbolise a globalised cultural industry. Nevertheless, they were often regarded as connected to the conceptual thinking of the above-mentioned Duchamp, making a conspicuous, albeit clear contribution to neo-avant-garde art.

Fig. 4: Hugo van Gelderen, A Fluxus concert at Kurhaus Scheveningen (1964), CC BY 1.0, Wikimedia, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Fluxus-groep_gaf_Pop-art_concert_in_Kurhaus,_een_van_de_bezoekers_schoot_met_een,_Bestanddeelnr_917-1243.jpg.

The idea of bringing art and life closer together was evident in small artistic ‘vanguard groups’ connected to the fringes of the so-called New Left, like the Situationists in France or the Provos in the Netherlands, intellectual and activist circles which promoted détournement and subversion as central elements of their artistic explorations, aiming at restructuring life in the city and ultimately transforming everyday life. Artistic creation was informed by the repertory of feast, play, poetry, and the ‘liberation of speech’, while its language was inspired by Marx, Freud, Nietzsche, Dadaism, and Surrealism. In terms of film, which increasingly gained territory as an artistic medium in society after the Second World War, there was a neo-avant-garde tendency, directly inspired by the tradition of the 1920s and 1930s.

The concept of ‘the underground’ was part and parcel of the avant-gardes of the 1950s and 1960s and directly linked to the writers of the so-called Beat Generation in the United States. It was associated with an alternative lifestyle that characterised itself through non-conformity and participation in so-called countercultures, such as the hippies, which contested the established ways of life. A spectacular fusion between ‘high’ and ‘low’ culture took place among young people who were influenced by such avant-garde circles and, consequently, between sophisticated intellectual items and popular consumer products. The irreverent posters, subversive poetry, and ironic writing on walls that were manifest in social movements with a utopian project, such as students’ mass protests against the bourgeois way of living and thinking in 1968 in Paris, Berlin, Rome, or Berkeley, betrayed the emergence of a new ‘structure of feeling’ in which irony and collective imagination were prevalent. This dialectic between playfulness and seriousness, engagé political action and everyday iconoclasm, illustrates the dichotomies, but also the pastiche and hybrid character of the 1960s artistic movements. Communitarianism as a lifestyle choice of the 1960s was a by-product of this. This phenomenon included rural hippy communes, more politicised communes (like Kommune 1 in West Berlin), or more experimental or artistically transgressive ones, such as the Friedrichshof Commune, founded by Austrian artist Otto Mühl. Inspiration for many of these communes, whether implicitly or explicitly, often came from earlier twentieth-century traditions. Consequently, earlier communitarian ideas, for example those of the German anarchist Gustav Landauer, regained popularity in the 1960s.

In Eastern Europe the rise of the neo-avant-garde had a lot to do with realising and formulating individual needs and rights as opposed to the compulsory and permanently declaimed priority of community interests. Socialist ideology, according to this section of the neo-avant-garde, was the oppression of any kind of individual way of thinking, looking or behaving. Being equal meant uniformity in everyday life. Although a critique of such practices had already been provided by the artists and underground movements of the above-mentioned generation of the 1960s, these artists tried to breathe life into that idea. To be underground in Eastern Europe in this period meant not only being different, but also being opposed to the state ideology.

Toward the end of the twentieth century, the legacy of the avant-garde movements became an integral part of contemporary artistic life as an inspiration for individual artists just like any other historical art movement. Arguably, the most important merit of the avant-garde is that it put such values as being different, open-minded, and experimental in the limelight, not only in arts but in all fields of social life.

Conclusion

The originality of the avant-gardes rests in their promotion of an idea of a radical beginning in all parts of life—a longing to create from a tabula rasa, to make a clean sweep of the past and to start afresh. In so doing, they sought to combine the freedom of the artist with that of art itself. In their art, the longing for a rupture with past conventions was both artistic and socio-political: art aimed to inspire a radical change of the socio-political world. Nevertheless, avant-garde art took very different shapes and forms throughout the twentieth century, reflecting the ideological prerogatives and political ambitions of the time. In this sense, it often ran parallel to the great political revolutions, world conflicts, and cultural revolts of the century. Especially the upheaval of the First World War, but also the rise of ideologies such as communism and fascism, had a direct impact on avant-gardist circles.

During the second half of the twentieth century, neo-avant-gardist artists retained a longing for experimental research and for rethinking and decompartmentalising social and political realities, hence they lost some of the strictly ideological edge of earlier manifestations. The avant-garde increasingly signified a fusion between arts and lived experience, whereby the idea of ‘underground’ as well as the fusion between ‘high’ and ‘low’ culture became pivotal. In the 1960s such circles gained currency, and their heterodox way of thinking or representing art ran parallel to or even directly reflected socio-political movements of the time—such as the global uprisings of 1968. Consequently, avant-garde artists contributed to putting values such as being different, open-minded, and experimental at the forefront of artistic endeavour, as well as of society at large. The seeds of that development continue to blossom up to the present day.

Discussion questions

- The artistic avant-gardes of the early twentieth century were thoroughly political. Why was this the case?

- In the 1960s, the differences between ‘high’ and ‘low’ culture in the works of artists became more and more blurred. Do you have an idea why this occurred?

- How do the avant-gardes of today differ from those of the early twentieth century, and why?

Suggested reading

Bürger, Peter, Theory of the Avant-garde (Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 1984).

Gay, Peter, Modernism: The Lure of Heresy from Baudelaire to Beckett and Beyond (London: Vintage, 2007).

Gough, Maria, The Artist as Producer: Russian Constructivism in Revolution (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2005).

Greenberg, Clement, Art and Culture (Boston, Beacon Press, 1961).

Poggoli, Renato, The Theory of the Avant-Garde (New Haven: Harvard University Press, 1968).

Piotrowski, Piotr, Art and Democracy in Post-Communist Europe (London: Reaktion Books, 2012).

Scheunemann, Dietrich, ed., European Avant-Garde: New Perspectives (Amsterdam: Rodopi, 2008).

Weber, Andrew, The European Avant-Garde 1900–1940 (Cambridge: Polity, 2004).

Willett, John, The New Society: Art and Politics in the Weimar Period, 1917–33 (London: Thames & Hudson, 1978).