7.2.3 Mass Media and Popular Culture in Contemporary History (ca. 1900–2000)

© 2023 Daniel, Lima Grecco, Tamagne, and Zierenberg, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0323.81

Introduction

The twentieth century witnessed the transformation of popular culture as well as an enormous growth in mass media’s power to inform (and form) societies. Both of these processes also gave birth to new fields of intellectual reflection: the study of popular culture and media studies. Every history of media and popular culture in the twentieth century, therefore, needs to reflect upon the actual evolution of different media structures and the growing contemporary awareness of the effects of mass media on society. Following these trends, this chapter first aims to provide the reader with an overview of theories reflecting the development of mass media in the twentieth century. Second, it gives specific historical examples of the power and control of media by fascist and Nazi regimes as well as with the far-right dictatorships on the Iberian Peninsula. Third, it will examine the theory of popular culture, discussing the case of different practices related to popular music.

Theories of Mass Media

Critical reflection about the changes that new media and new means of communication brought for modern societies began to take shape in the nineteenth century. One of the first authors who not only experimented with the possibilities of photography as a new medium but who also elaborated theoretically on its political utility was the American abolitionist Frederick Douglass (1817–1895). Douglass wrote four essays on the potential of photography in the struggle to democratise society and liberate slaves, evaluating the medium’s unique ability to represent slaves as human beings to a mass public and to document the horrific conditions of their enslavement in the American South and elsewhere.

Other authors of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries who began to discuss the overall effect of modern mass media on society included American sociologist Charles Horton Cooley (1864–1929). Cooley’s The Process of Social Change (1897), for example, underlined the chances he saw in the modern newspaper and other new means of communication to enhance public knowledge and to counter misinformation which, as he believed, lay at the heart of conflicts and wars. Here a topic entered public debate which would continue to be discussed throughout the twentieth century, namely the optimistic narrative of media change which tends to focus on the enlightening and democratising effects of new media, an interpretation that was echoed when the Internet began its growth as a medium. These theories became almost immediately countered by more pessimistic interpretations, a framing which led to two strands of media discourse that have been with us since the nineteenth century.

The establishment of a new field of knowledge dedicated to the study of media was inspired by various social, political, and cultural reorientations within a more complex media landscape in the first half of the twentieth century. In the context of the First World War and its aftermath—when state-driven propaganda and new ideas about the possibilities to inform or (mis-)lead mass audiences opened up new ways of thinking about media and their effects on society—the impact that single media or media ensembles have on individuals as well as on societies came under scrutiny. Some of the most prominent texts that still inform our interpretations today were written in the interwar period when systematic approaches to media communication became a common feature in different arenas of public life. Sociologists, critics writing for newspapers, ‘so-called newspaper scholars’, and psychologists—all professional observers of society—started to engage in a field of knowledge that might be called media studies avant la lettre. Two strands stood out. One of them was the approach that investigated the possibilities and the constraints of mass communication using empirical methods. Different actors from scholarly as well as political and commercial backgrounds engaged in these activities. The other strand of voices took a more critical, sociological approach. Theorists like Siegfried Kracauer (1889–1966) or Walter Benjamin (1892–1940) influenced and helped formulate the contemporary view of media as creating a new mode of communication which in turn sometimes also worked in favour of undemocratic or fascist political powers, and they also informed an influential way of thinking about media that (through the so-called ‘Frankfurt School’) still resonates as an interpretation of mass media communication today.

These two strands of research also influenced thought about media and society throughout the 1940s and into the Cold War era. Media theory is often described as having taken a turn in the 1960s with the establishment of university departments dedicated to its study and the growing prominence of Marshall McLuhan’s interpretation of the media as extensions of man’s bodily perceptual apparatus. Canadian media scholar Marshall McLuhan’s influential phrase—the “medium is the message”—conceptualised media not solely as the neutral transporter of particular content, but instead focused on the very process of communicating via media as a formative practice in itself that creates rather than simply identifies certain individual recipients or collective audiences. Nevertheless, one should not forget that some of these more structural aspects had already been discussed by Cooley and others. Furthermore, new approaches (from Deleuze, Foucault, and Kittler, among others) opened up new ways of thinking about media, which called for the analysis of the non-hierarchical, rhizomatic structures of digital communication and the overall importance of media as co-creators of the world we live in.

The example of McLuhan, however—who famously made a cameo appearance in Woody Allen’s film Annie Hall (1977)—speaks to a phenomenon that became more important during the second half of the twentieth century. Instead of remaining an experts’ discourse, reflection about what it means to live in an age of mass media and mass communication became part of a broader and much more popular conversation. Some of the most prominent analyses of the television era by Neil Postman and others broke new ground for a widespread and almost omnipresent discourse about media, digitalisation, and the fundamental shift of communication at the beginning of the twenty-first century. How digital media changed, and continue to change, media societies is very much a current question, although at least the battle of optimistic against pessimistic interpretations of mass media might remind us of the fact that these debates are well-established, and have a long history.

Mass Media under Control

Growing awareness of the potential power of mass media led to its strict control and its deployment for political goals. This can be well illustrated through the example of authoritarian regimes of the mid-twentieth century. Once in power in Italy and Germany, the fascist governments’ first objective was to enforce a particular ideology and implement the cultural policy necessary to maintain it. Thus, in contrast to the liberal state, the fascist regimes aimed to directly control both the sphere of culture, as well as a group of ideologically engaged intellectuals, where culture would be tied to the political objectives set by the state. As such, the newspaper and literary industry were to be controlled entirely by the government.

In line with this approach, the Italian Fascist regime (1922–1943), ruled by Benito Mussolini, sought to erect a fascist national culture. Some artists, such as the poet Filippo Marinetti or Gabriele D’Annunzio, provided the building blocks for a new art inspired by violence, war, and aggressive nationalism. Under this approach, all artistic creation was meant be in tune with the new regime, and—because of that—Mussolini ordered the confiscation of newspapers and books that criticised the regime. The Ufficio Stampa della Presidenza del Consiglio was the institutional body in charge of controlling literary production. Moreover, the Italian Academy compiled a list of books which they believed should be banned, and in 1939, a purging policy was set in motion which prohibited more than 900 texts.

A similar process took place with the Third Reich´s Black List under the Nazi regime (1933–1945), and towards the end of 1938 the number of banned books in Germany rose to 4,700, including texts written by Bertolt Brecht, Emil Ludwig, and Oskar Maria Graf. In order to ensure this prohibition was effective, combat committees were formed and assigned the task of registering private bookshops or commercial libraries, and confiscating thousands of texts to be destroyed and burnt. The ritual of a public burning incited terror in the spectator, but also a shared sense of belonging to a symbolic community. This type of public ceremony was carried out from the early years of the rise of Nazism. On 10 May 1933, thousands of books were burned in Berlin’s Opera Square, in the presence of a large number of students who emitted cheers each time a book was thrown on to the flames.

Fig. 1: Georg Pahl, Book burning by students on Berlin’s Opernplatz (1933), Public Domain, Wikimedia, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Bundesarchiv_Bild_102-14597,_Berlin,_Opernplatz,_B%C3%BCcherverbrennung.jpg.

In line with their overall totalitarian agenda, the Nazis sought control of all expression of culture and thought. Both in the media and in the arts, they attempted to purge all traces of liberal or Marxist values, and any kind of critical, progressive, or pluralistic thinking. These values and perspectives were indistinctly termed ‘decadent’, ‘Jewish’, ‘Bolshevik’, or ‘black’. On 4 February 1933 Hitler persuaded President Paul von Hindenburg to sign an emergency decree (Verordnung des Reichspräsidenten zum Schutze des Deutschen Volkes), which authorised the state to prohibit publications or meetings that “abused or treated official bodies or institutions with contempt”, and as a result of this decree, many communist and social democratic newspapers were suppressed.

On the other hand, writers such as Friedrich Griese or Ina Seidel were distinguished novelists who participated in the nationalist literary movement during the Third Reich, and who endeavoured to construct an idealised conception of the German ‘spirit’. Creative work represented an opportunity for the Third Reich to unify the national community based on themes which found their main source of inspiration in the experience of war. The press, the radio, cinema, literature, libraries, the university and schools served to diffuse the Pan-Germanic ideal and brought the masses into line with the regime. In 1937, rural novels, historical novels, and novels set in the native landscape were bestsellers. From 1939 onwards novels glorifying the initial struggles of the Nazi Party moved to the top of the list. Despite this, these low-quality novels were only momentarily successful and, as a result of the exile of important communist, liberal, and Jewish writers, German literature within the country itself suffered a decline in quality and diversity.

In other European dictatorships, such as those of Francisco Franco (Spain, 1936–1975) or António de Oliveira Salazar (Portugal, 1926–1974), censorship was also widely used. Franco and Salazar believed that culture and the press should serve the national community and adapt to ‘the official version of the facts’, and censorship had the goal of entirely obstructing subversive ideas that could breed dissent. In Spain, the Law of 22 April 1938—which was in large part inspired by new fascist legislation in Italy—established an a priori process for the censorship of books and newspapers. On the other hand, in Portugal, the regime counted on António Ferro as director of the National Propaganda Secretariat, which was the organ par excellence for Salazar propaganda and censorship. Texts of a political or social nature were forced to be submitted to prior censorship before publication.

Theories of Popular Culture

The concept of popular culture relates to the everyday culture of the general public and encompasses mainstream culture as well as its subcultural counter-narratives. On the one hand, popular culture in particular historical times and spaces referred to the traditional patterns of culture (preserving folk besides the newly-developed mediatised cultural production). But on the other hand, popular culture simultaneously became consciously fashionable and globalised.

Departing from the notion of cultural capital as formulated by French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu (1979) as a tool for distinguishing social groups, we may view distinct musical tastes in a similar way to tastes in any other cultural field: they reflect status inequalities based on their bearer’s socio-economic position, education, and networks. One large-scale study in the United Kingdom, conducted by a group of British researchers, defended this model against critiques drawn from US research in the 1980s. The upper classes, the UK researchers found, were not omnivorous music consumers as the US study had claimed. Rather, music was a contested cultural field where certain borders would not be crossed.

Views radically different to those of Pierre Bourdieu, as well as those of the theory of mass culture elaborated by the Frankfurt School, were championed by scholars from the Centre for Contemporary Cultural Studies (CCCS) at the University of Birmingham, the so-called Birmingham School. In their predominant view from analysis of working-class culture, culture was conceived as a site of struggle for hegemony. Stuart Hall and other writers participating in this current followed a line of Marxist thought represented by Italian theorist Antonio Gramsci and German philosopher Louis Althusser, giving importance to ideology and the different means of its reproduction.

Since the 1990s, with a shift of interest from the culture of the working class towards the cultural activities of the middle class, scholars like the British sociologist Beverley Skeggs drew upon the tradition of cultural sociology, adding two important dimensions: gender and race.

Although in the nineteenth century, popular music referred to work songs and traditional melodies collected by folklorists, in the twentieth century, it more and more came to designate a commodified genre produced by the record industry and broadcasted by mass media. As such, it was strongly criticised by intellectuals from the Frankfurt School, who analysed pop music mostly in terms of standardisation and easy consumption, a point of view contested in the 1970s by sociologists from the Birmingham School, who preferred to emphasise the listeners’ agency and the way popular music could participate in the construction of individual, social, and political identities.

Popular Music

Popular music witnessed dynamic evolution over the course of the twentieth century, with the emergence of new styles and genres, as well as technological innovations and the changing social functions of music. At the beginning of the twentieth century, music-hall, a theatrical genre which involved a variety of popular songs and speciality acts, established itself as one of the favourite forms of entertainment in Europe. Revues, which eroticised female bodies, triumphed on the Parisian stages of the Folies Bergère or Moulin Rouge, while the 1920s saw the golden age of German cabaret, with composers such as Kurt Weill and vocal groups such as the Comedian Harmonists, whose careers were interrupted by Nazism. Artists like Maurice Chevalier or, later on, Edith Piaf benefited from an international reputation. North American influences were also obvious at the time, whether in the form of jazz or swings bands, or of Tin Pan Alley standards, interpreted by crooners such as Bing Crosby, or later Frank Sinatra.

Born in 1954 in the United States, rock ’n’ roll conquered Europe through juke-boxes, the cinema (with films like Richard Brooks’ The Blackboard Jungle from 1955), international radio stations (such as American Forces Network or Radio Luxembourg), and television shows (such as the British shows Ready, Steady, Go! and Top of the Pops, launched in 1963 and 1964, respectively), but also local imitators, such as Johnny Hallyday in France and Cliff Richards in Britain, who covered American hits. Hailed as the music of teenagers, rock ’n’ roll was nonetheless associated in the media with juvenile delinquency and sexual promiscuity. Rock music was also part of the Cultural Cold War between East and West. While the Voice of America radio station broadcasted Western popular music in Eastern Europe, countries such as the GDR tried to censure beat groups.

Notwithstanding cultural Americanisation, national music genres, such as the French chanson, the Italian musica leggera, or the German Schlager, remained very popular locally. From the 1960s onwards, the ‘British Invasion’, with bands such as the Beatles or the Rolling Stones, and, later on, Krautrock bands of the 1970s, or French Touch house music of the 1990s, demonstrated the—often short-lived—capacity of European pop music to be successfully exported. On the other side, European artists, following the example of the British pop musician George Harrison learning sitar, became more and more open to non-Western musical instruments and sounds. Despite some racist outbursts, reggae was also favourably received in Britain.

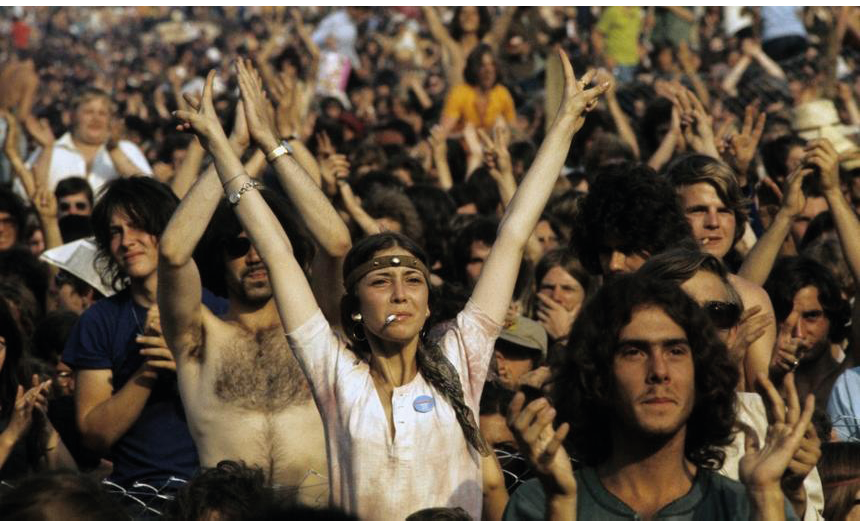

Popular music could also convey political or counter-cultural demands. From the 1950s onwards, folk music, following the examples of artists such as Bob Dylan or Joan Baez, gained more and more support in Europe, being used for example during the British anti-nuclear Aldermaston marches. From the 1960s onwards, psychedelic rock, born in San Francisco, but relayed by British bands like Pink Floyd, became the soundtrack of the hippie revolution. Music festivals, such as the Isle of Wight Festival of 1970, attracted hundreds of thousands of young people, although such festivals were sometimes forbidden in France, Germany, or Italy, for fear of unrest.

Fig. 2: Young people listening to the bands at the Isle of Wight Festival, 1970, CC BY-NC-SA, Rolf M. Aagaard, Aftenposten, NTB scanpix, https://ndla.no/subject:52b154e8-eb71-49cb-b046-c41303eb9b99/topic:105e337f-4f5f-4b24-a6d3-9d1835094e15/topic:a1595e33-1e32-4c7d-a0e8-c6a6bfd33545/resource:c92b951f-e877-4083-ba5e-a124d935c166.

Although rock music had gone mainstream by the middle of the 1970s, some genres—such as glam rock, by challenging gender norms, or punk rock, with its anti-establishment stance—could still be viewed as subversive. In the 1980s and 1990s, other successful popular music genres, such as electronic music and hip-hop, were the subject of moral panics, either because of fear of drug abuse or allegations of violence. Nevertheless, even highly commodified events, such as the Eurovision Song Contest (created in 1956), can function as a platform for political or social demands, for example regarding LGBT+ rights.

After the Second World War, new formats and equipment, such as LPs and single records (1948–1949), high-fidelity and stereo recording in the 1950s and 1960s, audio tape recorders (1948), and synthesisers (1964) revolutionised the record industry, generating spectacular growth. The 1980s saw new technical innovations such as the compact disc (1982), as well as the emergence of music videos and a new way to experience music thanks to portable cassette players like Sony’s Walkman (1979). Although the record industry has always been dominated by a few major labels, independent record labels have contributed to the dynamism of the music scene, by supporting music genres held as non-profitable by big companies.

Conclusion

European societies in the twentieth century have witnessed an unprecedented growth of mass media and its applications. Media was gradually exploited by both democratic and non-democratic regimes, market and state-controlled economies—by different political and economic regimes for their own purposes. Similarly, popular culture became more important for Europeans of the twentieth century, not only as a tool of state propaganda but also as a means of self-identification and resistance, which is perhaps best illustrated in the case of different uses of popular music.

Discussion questions

- How did the ways in which people thought about popular culture and music change over the course of the twentieth century?

- Why did the authoritarian regimes of twentieth-century Europe try to control popular culture and music?

- In this article, popular culture is described as a site of political struggle. In which ways was popular culture politicised in the twentieth century? Can you think of similar examples from today?

Suggested reading

Bennett, Tony et al., Culture, Class, Distinction (London: Routledge, 2009).

Bourdieu, Pierre, Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1987 [1979]).

Frith, Simon, The Cambridge Companion to Pop and Rock (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001).

Longhurst, Brian, Popular Music and Society (Cambridge: Polity Press, 1995).

Peterson, Richard A. and Roger M. Kern, ‘Changing Highbrow Taste: From Snob to Omnivore’, American Sociological Review 61:5 (1996), 900–907.

Skeggs, Beverley, Class, Self, Culture (London: Routledge, 2004).