7.3.3 Sports and Leisure in Contemporary History (ca. 1900–2000)

© 2023 Dirven, Mendoza Martín, Reichherzer, and Lesage, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0323.84

Introduction

The twentieth century was characterised by a great expansion of ‘free’ time—time that was not taken up by work or other duties, and was at the disposal of individuals to fill as they pleased. Through changes in legislation and technological developments, ever greater parts of the population in Europe could enjoy this privilege of ‘free’ time. However, it is uncertain how ‘free’ people really were in their choices of leisure activities. Throughout the twentieth century, modern pressures and social constraints like self-control or body image shaped the ways that free time was spent in Europe.

Freeing up Time? Modern Experiences of Sport and Leisure in the Twentieth Century

The concept of ‘leisure’ is an invention of modern times, which began to develop in the mid-nineteenth century. In the twentieth century a greater number of people gained access to free time, which they spent on different types of leisure activities. The democratisation of leisure was made possible when trade unions started to contest the long working hours of the working classes, and gradually achieved the regulation of the day into eight hours of work, eight hours of sleep, and eight hours of free time. As a growing group of people thus gained the opportunity to use their spare hours as they wished, questions arose about how free time could, and should, be spent.

Throughout the twentieth century, one answer to this question was offering people the opportunity to go on holiday. The worker’s right to holiday was first made possible by the extension of the welfare state, which gradually came to include paid holidays. In 1936, France established two weeks of paid holiday. In Great Britain, a week’s holiday became available in 1938. Thanks to the regulation of working hours and modern means of transportation—such as the railway, and later the car and the plane—the twentieth century saw the gradual evolution of tourism from a unique activity for the elite to a set of practices involving wider circles.

The same evolution occurred in sport. During the nineteenth century, the aristocracy was the social class with the greatest access to sport, and the most popular sports were activities like horse riding. Non-aristocratic classes had access to sport as a form of pastime that became established over time through, for example, the establishment of football matches related to political associations or trade unions. In the case of dance culture, dancing had long been organised along the lines of social class. In the twentieth century, by contrast, it became an integral part of urban nightlife, with people from diverse social backgrounds crossing paths and all doing the same, popular dances.

The increase in free time and the development of new leisure activities were conceived as ‘modern’. These changes were not only made possible by modernisation processes, such as the development of new forms of transport, they also offered people a way to make sense of the new epoch in which they were living. In other words, it allowed them to experience and cope with the fast-changing society of the twentieth century.

On the one hand, this development of more free time and more leisure activities could be seen as a progressive development: it was exciting to engage with leisure activities related to new technological developments, gender emancipation and urbanisation. On the other hand, the development of ‘free’ time could also serve as a reminder of constraint and discipline. How much freedom people actually enjoyed in their ‘free’ time is debatable. For many people, engaging in these activities functioned as a way to escape from a fast-paced and depersonalised modern society, which was perceived as alienating and overwhelming. In addition, leisure time was controlled and mediated by different entities, such as governments, states, sporting associations, and social organisations, or NGOs. These groups managed to limit when, where, and how society could spend its free time and even, in some cases, prescribed how individuals could move their bodies. As the century went on, people internalised this regulation of leisure time and bodily control and aimed for self-regulation in their leisure activities.

In sum, modern sport and leisure can simultaneously be understood as an experience of freedom and a practice of constraint. In this respect, the democratisation of leisure activities illustrates the ambiguous nature of modernity and the complex experience of living through the twentieth century.

Modern Sport: Making Sense of Free Time

A city map of Berlin, published in 1928, listed sporting facilities in the city for different kinds of activities—like athletics, cycling, swimming, sailing, field games and many more. In less than twenty years, the number of sports grounds increased from twenty-five before the First World War, to 324. The immense widening of the ‘sportscape’ was not only a phenomenon of metropolitan areas. Around the 1920s, smaller cities, towns, and even villages constructed play- and sports-grounds. During the twentieth century, playing and even spectating sports became an important phenomenon of mass culture and a leading leisure activity for men and women, old and young, poor and rich, urbanites and countrymen alike. However, sport was more than pure fun or entertainment. The twentieth century saw the developments of the spatialisation and commodification of free time, and the rise of a sports and leisure industry. In modernity, physical exercise became a powerful tool for both making sense of and colonising free time.

Even if sport was often labelled as ‘free’ leisure activity and dissociated from work, the realm of sport was nonetheless ‘utilised’ for other purposes. Sport evolved as a powerful biopolitical device (Michel Foucault) through which to administer life and populations. During the first half of the century, physical exercise was seen as a proper means for the ‘right’ use of time. Play and sport provided an important and effective instrument for the ‘improvement’ of society. It was seen as a tool to tackle the alleged degenerative effects of industrialised modernity and to cure the ills of modern life, which ranged from unhealthy working conditions to loitering, idleness, and drinking, or other ‘deviant’ patterns of life and behaviour.

By the nineteenth century, sport became obligatory in schools in many countries across Europe. Social reformers, politicians, and government officials believed that sport could enhance collective moral values and the physical strength of society. Representing a fundamentally modern approach, these policies were implemented in liberal democracies, as well as in fascist, socialist, or authoritarian regimes—even if these modern forms of government differed in their ultimate aims, the ways in which they intervened in personal freedom, and the manners by which they exerted social control. Indeed, in twentieth-century Europe, the striving for betterment and control went hand-in-hand. This was as true for the private sector as it was for governmental organisations. Since the early twentieth century, companies and factories had built sports grounds and used sports as incentives for employees and as means of control for their life after work. Even the military used sports in peacetime as a body-, mind- and character-building force as well as a means of organised entertainment and restoring order and discipline during the World Wars.

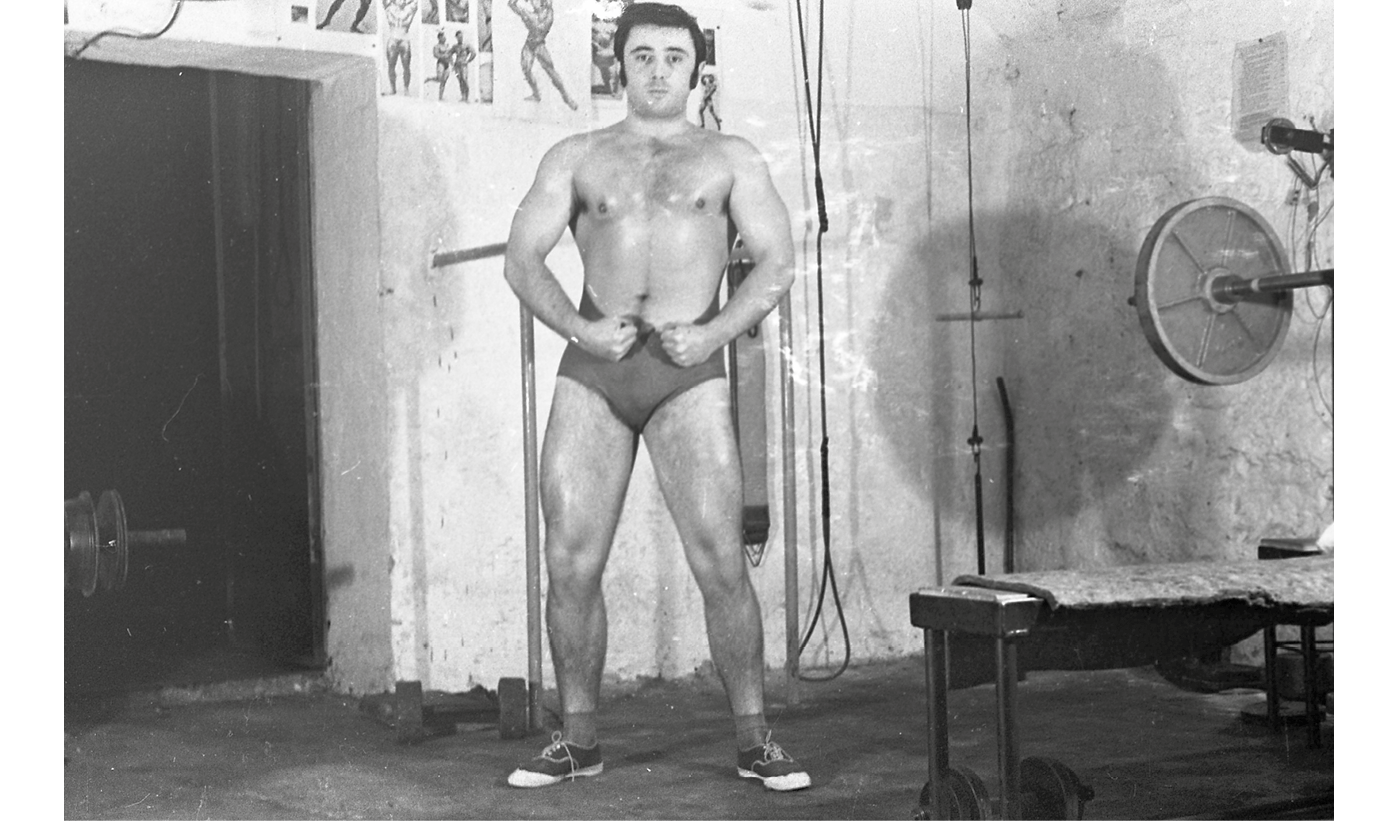

In the late twentieth century, during what has been termed the ‘Age of Fitness’ (Jürgen Martschukat), sport lost its claim to bettering societies. Forms of regulation shifted from state, government, and civil society to self-regulation. Since the 1970s, sport has addressed the individual. Running in parks, doing aerobics (or later yoga) in front of the television, working out in gyms and other forms of lifestyle sports are bodily practices that focus on the optimisation and enhancement of human capabilities in all aspects of life. For example, someone might see it as a duty to go jogging before or after office hours to obtain a healthy, energetic, and even sexually attractive body. Increasingly, as a leisure activity, individual sport has become work, or a way to work on oneself.

Fig. 1: Tamás Urbán, Bodybuilder in the gym of Vasas Kismotor és Gépgyár Sport Klub, Budapest (1970), Wikimedia, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Sneakers,_gym,_dumb-bell,_body_building,_muscle_Fortepan_87118.jpg.

Looking back at sport in the twentieth century, one thing becomes clear: the boundaries between work and leisure—the normative setting of eight hours of work, eight hours of rest and eight hours of ‘free time’—were porous, if not fractured. In the modern age, as people strove to achieve an unquestionable order and a functional differentiation of time, free time was never really free—all the more so, because leisure could not exclusively be pleasure. In sports, the ambiguities of the modern condition become apparent. Time was not permitted to be ‘empty’ or ‘wasted’, and sport was intended to make sense of time.

Shake, Shimmy, and Twirl: Modern Excitement in the Dutch Interbellum Dancehall

In the early twentieth century, social dances, such as the two-step, the turkey trot, the tango and the Charleston, made their way into Western European ballrooms, restaurants and dancehalls. These ‘modern dances’, as they were called, had developed in the United States and Latin America (in the case of the tango). To execute them, couples stood in a close embrace and were encouraged to wildly and loosely move around the dancefloor, kicking their legs and shaking their torsos. Especially during the roaring twenties, this new style of dancing became immensely popular in Western European cities such as London, Paris, The Hague, and Berlin. It offered growing groups of young, urban, and increasingly female professionals new and modern ways to use and display their bodies, engage with members of the opposite sex, encounter people of other social classes, and cope with the changes in modern society.

This new experience excited many, but also aroused moral panic. For example, critics in the Netherlands wondered whether these American dances were too superficial for ‘intellectual’ and ‘elegant’ Europeans. And there was also the question of whether the assumed sexual nature of the dances morally degraded the dancers. As a social debate developed in the Netherlands about the suitability of American dance culture for Europeans, the dancehall became a space where different experiences of modernity came together and were negotiated.

The dances offered many people a way to cope with the urbanised and industrialised society of the early twentieth century. The quick and wild movements required to execute the dances reflected the rushed and fast-changing way of life in the modern, industrialised metropolis. Simultaneously, a night in the dancehall could be a way for people to escape from modernity. It was a way for people to cope with the individualised industrial mass society in which they were becoming more estranged from each other and from the work they did. It offered people an escape from their daily lives and the opportunity to keep fit or at least to reconnect with their bodies after sitting for long hours at the office. Moreover, some dancers came to dancehalls to overcome the modern feeling of ‘estrangement’ and argued that dancing could trigger instinctive, primal emotions that allowed people, if only for a moment, to experience a connection to each other.

However, not everyone believed that the dancehall offered a means for coping with modernisation. Cultural critics and religious organisations doubted that such superficial experiences could remedy the loss of interpersonal connection in modern life. Moreover, they were suspicious of ‘modern’ interactions between men and women on the dance floor.

The debate that followed this critique offered people a platform to make sense of the rapidly changing gender norms and sexual mores during the interbellum. The dancehall was a space where members of the opposite sex from different social backgrounds, unchaperoned, could jointly spend their leisure time. Moral panic arose about this new social arrangement, especially because the African-American dances were considered to be sexual in nature. Influenced by racist ideas, cultural critics, dance teachers and Dutch governmental committees suggested that the people of colour who had developed these dances expressed their perceived ‘primitivism’ and ‘hypersexuality’ through the wild movements of jerking torsos, swinging hips, and shuddering shoulders. These officials considered such an inflammatory display of ‘primal’ and ‘sexual instincts’ inappropriate for ‘modern’ Europeans who they believed to be ‘civilised’ and ‘intellectual’. They feared that participation in such movements would arouse dancers’ sexual desires and lead to immoral behaviour, such as pregnancies out of wedlock.

An easy and modern remedy to this was found in the regulation of the dancehall and the discipline of dancers. Dance teachers adapted African-American dances, rejecting the wild movements and developing strict guidelines for male-female interactions to allow the dancers to retain a sense of ‘elegance and modesty’, which they considered to be representative of ‘European values’. Moreover, the Dutch government and municipalities started to regulate the space of the dancehall, for example by issuing laws on alcohol consumption and limitations on the maximum number of visitors allowed. Regulated in this way, parents, dance teachers, and governmental organisations believed that the dancehall offered young men and women a modern space for a traditional goal: finding a marriage partner.

However, a growing group of women were not so eager to adapt their behaviour or to conform to this normative ideal. For them, dancing was not a modern means to a traditional end. It was fun. They enjoyed the flirtations, the sensual experience of being held by different men and the ability to move their bodies more freely. This sometimes led to frustrated or even aggressive responses by their male partners. In effect, for women, the dancehall was a place where they simultaneously experienced sexual liberation and attempts to discipline their bodies according to traditional gender ideals.

The dancehall was a modern space par excellence. It was an ambiguous place that brought together ideas about ‘primitive’, ‘traditional’, and ‘modern’ bodies. Most importantly, dancing offered people the opportunity to experience both the excitement and the anxieties that the new age offered.

Sea, Sex and Sun: Mass Tourism and the New Geography of Leisure

In the twentieth century, debates about the regulation of time raised the possibility of providing people with a few weeks of time off work, and paid holidays were legally regulated in various European countries. The right to holidays was officially endorsed by the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (Article 24) adopted by the United Nations in 1948 and, consequently, mass tourism became a reality in Europe. However, the question did not end with simply granting holidays to people: governments and philanthropic movements undertook measures to supervise the masses of people now accessing leisure. For instance, it was the desire to provide healthy, supervised leisure activities for young workers that gave rise to youth hostels in Germany at the turn of the century.

In the 1960s, there was a massification of access to holidays, growth in the tourism industry, and the establishment of leisure mobility as a social norm. This led to a collective and individual increase in tourist consumption, which is reflected in the high share of leisure and holiday expenditure in household budgets. These changes brought about a transformation in transport which redrew the map of European tourism. Individual cars and highways and planes and airports provided access to areas that, in turn, began to progressively specialise in welcoming tourists. Great summer migrations from the northern countries to the new seaside resorts, particularly in Spain, became widespread throughout Europe. If the car allowed and conditioned the considerable tourist boom of the 1950s-1970s, the last decades of the century saw a boom in air travel, which became increasingly accessible for more and more people. The opening of Malaga Airport in 1968 accelerated the urbanisation of the Costa del Sol thanks to charter flights. In addition, from the 1990s onwards, the appearance of low-cost flights further amplified this dynamic to include other parts of Eastern Europe, such as the Dalmatian Coast.

The development of tourism as a mass phenomenon was finally made possible and supervised by major development projects that changed the scale of leisure infrastructures. La Grande-Motte beach resort, on the French Mediterranean Coast, is an example of these logics, between the promotion of a social ideology and regional planning. In contrast to the uncontrolled development of tourist urbanisation on the Côte d’Azur, the French government wanted to take advantage of the desire for holidays to redevelop the Languedoc coastline. In the 1960s, the French government cleaned up the mosquito-infested swamps that lined the beaches and built large resorts capable of absorbing tourist flows, revitalising the regional economy, and attracting French and foreign tourists to deflect competition from the Costa del Sol. In this respect, the beach can be seen as constructed by local and national governments and companies, working together with different but converging interests: planning urban development, structuring a new sector of touristic service, and shaping new bodies.

Fig. 2: Tourists at the Costa Brava in Spain (1991), CC BY 3.0, Wikimedia, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:August_Playa_Sol_Roses_-_Mythos_Spain_Photography_1991_-_panoramio.jpg.

Compared to the previous century, tourist use of beaches differed not only in the scale of development but also in the affirmation of new bodily practices. The upwardly mobile middle classes imposed faddish new standards of bodily behaviour, such as tanning or semi-nudity. The beach thus appeared as an emancipating space that allowed for separation from the roles of daily life, a blurring of social differences, and a favouring of expressions of individuality. It could be seen as a place of political, social, and economic struggle where, at least temporarily, social identities were erased and transformed.

Conclusion

During the twentieth century, some of the trends of the nineteenth century, such as massive population growth and the development of leisure as a daily activity, became firmly established. As the hours of the day were increasingly allocated to specific functions (sleep, work, and recreation) more people could enter leisure spaces. However, the granting of ‘free’ time also brought with it attempts to regulate and control that time from different entities—states, governments, parties, companies, industries, activists, and other agents of civil societies.

The experiences cited above demonstrate the multifaceted nature and ambiguities of modernity. Modernity was a complex phenomenon that provided new freedoms, but also new constraints. As such, historians dealing with sport and other leisure activities should always ask how these ‘lands of freedom’ were repeatedly framed, constituted, used, colonised, and ordered.

Discussion questions

- To what extent did organisational, social and cultural pressures and constraints shape the way people filled and experienced their leisure time in the twentieth century? Can you think of others that do not appear in the text?

- In which ways were holidays a counterpoint from ‘normal’ life? Why do you think people thought this difference necessary?

- Can you think of any constraints that shape the way you fill your free time? Are they different to those that were predominant in the twentieth century?

Suggested reading

Bale, John, Sports Geography (London: Routledge, 2003).

Borsay, Peter, A History of Leisure: The British Experience since 1500 (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2006).

Campbell, Timothy and Adam Sitze, eds, Biopolitics: A Reader (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2013).

Corbin, Alain, L’avènement des loisirs: 1850–1960 (Paris: Flammarion, 1995).

Kuchenbuch, David, Pioneering Health in London 1935–2000: The Peckham Experiment (Abingdon: Routledge, 2019).

Martschukat, Jürgen, The Age of Fitness: How the Body Came to Symbolize Success and Achievement (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2021).

Snape, Robert, ‘Continuity, Change and Performativity in Leisure: English Folk Dance and Modernity 1900–1939’, Leisure Studies 28:3 (2009), 297–311.

van Eijnatten, Joris et al., ‘Shaping the Discourse on Modernity’, International Journal for History, Culture and Modernity 1:1 (2013), 3–20.