Introduction

© 2022 Hansen, Hung, Ira, Klement, Lesage, Simal, and Tompkins, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0323.88

What is European history? A.J.P. Taylor once quipped that “European history is whatever the historian wants it to be.” This is certainly an appropriate account in that Taylor refers to the constructive nature of historiography, emphasising that it is the historian who ‘creates’ his or her subject matter. However, Taylor’s definition is also problematic because his choice to use the singular “historian” implies that writing history is a solitary endeavour, the imprinting of one mind onto the page. Nothing could be further from the development process of the present handbook of European history. It is a collaborative effort of nearly a hundred historians from seventeen European universities and research institutions, each individual with their own ideas about European history shaped by their personal backgrounds, national contexts and academic traditions. The resulting muddle is our answer to the question about the nature of European history: it is complicated, polyvocal (sometimes in harmony, often not), multi-layered and complex. The pedagogical term for this approach is ‘multi-perspectivity’, in which different perspectives are used to evaluate historical events and processes. In the words of a group of Dutch researchers led by Bjorn Wansink, in the context of history education the notion of multi-perspectivity refers to “the idea that history is interpretational and subjective, with multiple coexisting narratives about particular historical events.” The core of what European history means to us is expressed in this quote.

The subject of European history has recently been the topic of a vigorous debate among historians. One group has argued that European history should be “about what could be called ‘doing European History’: empirical research that transcends the nation-state in various ways—e.g. projects which are conceived in a transnational, comparative, trans-local way and which at the same time are located in Europe in one way or another.” We broadly align ourselves with this self-reflexive approach. We argue that the subject matter of a handbook on European history does not in itself constitute a contribution to European history. Whether a work makes a contribution to European history depends not only on the topics and historical events it addresses, but above all on its questions, its perspectives, and the way it analyses and narrates. Despite all the differences in detail, European history as a perspective, approach or method is characterised by at least four features: first, it is driven by an effort to narrate historical processes from multiple or comparative perspectives, be they national or regional, global or local, macro or micro. Second, it emphasises processes of mutual interaction, exchange, and transnational contact (also with non-European or colonial spaces) without overlooking local specificities. Third, the European history approach emphasises the contingency of the historical process and avoids narratives of progress toward ever-increasing civility. The Russian war of aggression against Ukraine that started in 2022 is a painful reminder of how fragile peace in the twenty-first century still is. Fourth, it uses its insights into the past to reflect on the present. That does not mean that the historian should become a political advisor or even an apologist for the process of European unification, but that she can offer a reflected commentary on the historical roots of the present.

This handbook is not only rooted in conceptual reflections about the nature of European history. It also grew out of very practical considerations about how to teach European history in the twenty-first century: universities in Europe are internationalising rapidly, welcoming students from all over the world. This raises important questions about how and what to teach this increasingly diverse student body. What kind of European history is appropriate for, say, an Italian undergraduate student enrolled in a BA History programme delivered in English at a Dutch university, or for a Syrian national studying (likewise in English) at a Polish university? With the continuing process of internationalisation in higher education, Brexit and immigration restrictions all making studying at British universities for students from EU member states and non-EU students ever more difficult, this experience is becoming increasingly common.

Furthermore, European history is not only taught in Europe. What is the right kind of European history for, say, a student in Singapore taking a module on social movements in early modern Europe? If European history is whatever we want it to be, there is a clear mission to create appropriate material with which to teach this increasingly internationalised student population.

Universities in continental Europe have set up a great number of English-language programmes over the past decades, including in history. The need for more English-language programmes and modules has long been highlighted in national internationalisation strategies. For example, in 2012 the German Action Committee on Education (Aktionsrat Bildung) emphasised the central importance of the internationalisation of teaching at German universities, particularly of curricula: “if the attractiveness of German universities for Erasmus students should be increased, the number of courses in English needs to be increased.” But, as the Dutch Association of Universities (VSNU) remarked in 2018, internationalisation not only means English teaching material, but also “the integration of cross-border issues, intercultural skills and diverse cultural perspectives in the curriculum.” Until now, English-language textbooks about European history were often written from the implicit or explicit national perspective of their anglophone (principally British or American) authors. A truly international curriculum, as the intended result of an internationalisation of history education at institutions of higher education, needs to reflect the complex and transnational nature of European history in both content and structure. The aim must be to balance linguistic internationalisation in the form of English instruction with a truly European approach to the content taught. We hope that this handbook will contribute to this undertaking.

Our author teams are sourced from seventeen universities in the Czech Republic, France, Germany, Hungary, the Netherlands, Norway, the United Kingdom, and Spain. Our vision was that each chapter would be written by an international team of authors from at least three of these countries. We did not always succeed in fulfilling these aims. While the majority of the chapters were written, as planned, by groups of three or four authors based at different European universities, this proved impossible for some chapters, either because of a lack of expertise in our team (this was the case for early modern history) or because historical events affected our project of writing history: for the most part, this handbook was produced during a global pandemic, successive lockdowns and under the threat of serious illness, which took a toll on our authors, their families and the project itself. People fell ill or were required to care for sick relatives and could not contribute as they had intended. We had elaborate plans for international project meetings and writing retreats in which authors would dedicate themselves to writing multiperspective takes on European history. Instead, we discussed plans in lengthy online meetings, wrote and edited from our home offices, while nursing crying children, struggling with isolation and loneliness, or recovering from serious illness.

While this partly derailed our plans—as happens with even the best-laid ones—it did not undermine the purpose of this handbook. What we aimed to do was to provide examples of ‘doing’ European history, or case studies that can be used to teach students what a multiperspective approach to European history might look like.

This is why this handbook is not structured simply by important events in European history—from the French Revolution to the fall of the Berlin Wall—but by themes that cut across national boundaries and transcend clearly demarcated historical trajectories. Each chapter shows how the respective topic played out differently in early modern, modern and contemporary history, in different European contexts. The chapters are broadly comparative, offering national case studies to highlight the variety of the European experience. The aim was not to offer another master narrative of European history. The aim was not to provide a comprehensive, exhaustive account of European events from all possible viewpoints, replacing a single national perspective with a collection of national perspectives. How many national perspectives would one need to create the European perspective, anyway? Five? Ten? Twenty-seven? Completeness, even if it were attainable, is not the answer. Paul Dukes, himself a renowned expert in European history, argued that “European history must be more than the sum total of its constituent parts.” For us, European history is not a body of knowledge, but a method, an approach.

This means that readers will always find important omissions. Due to the nature of our team and the focus of this project, certain perspectives (e.g. Scandinavian, south-eastern European, Polish or non-European and colonial experiences) are sometimes underrepresented. We have tried to address these gaps by providing relevant secondary literature in the bibliography of each subchapter. We hope, however, that this handbook succeeds in demonstrating the heterogeneity and complexity of the many different development paths within (geographic) Europe, with attention to how these paths were linked to, and dependent on, non-European developments.

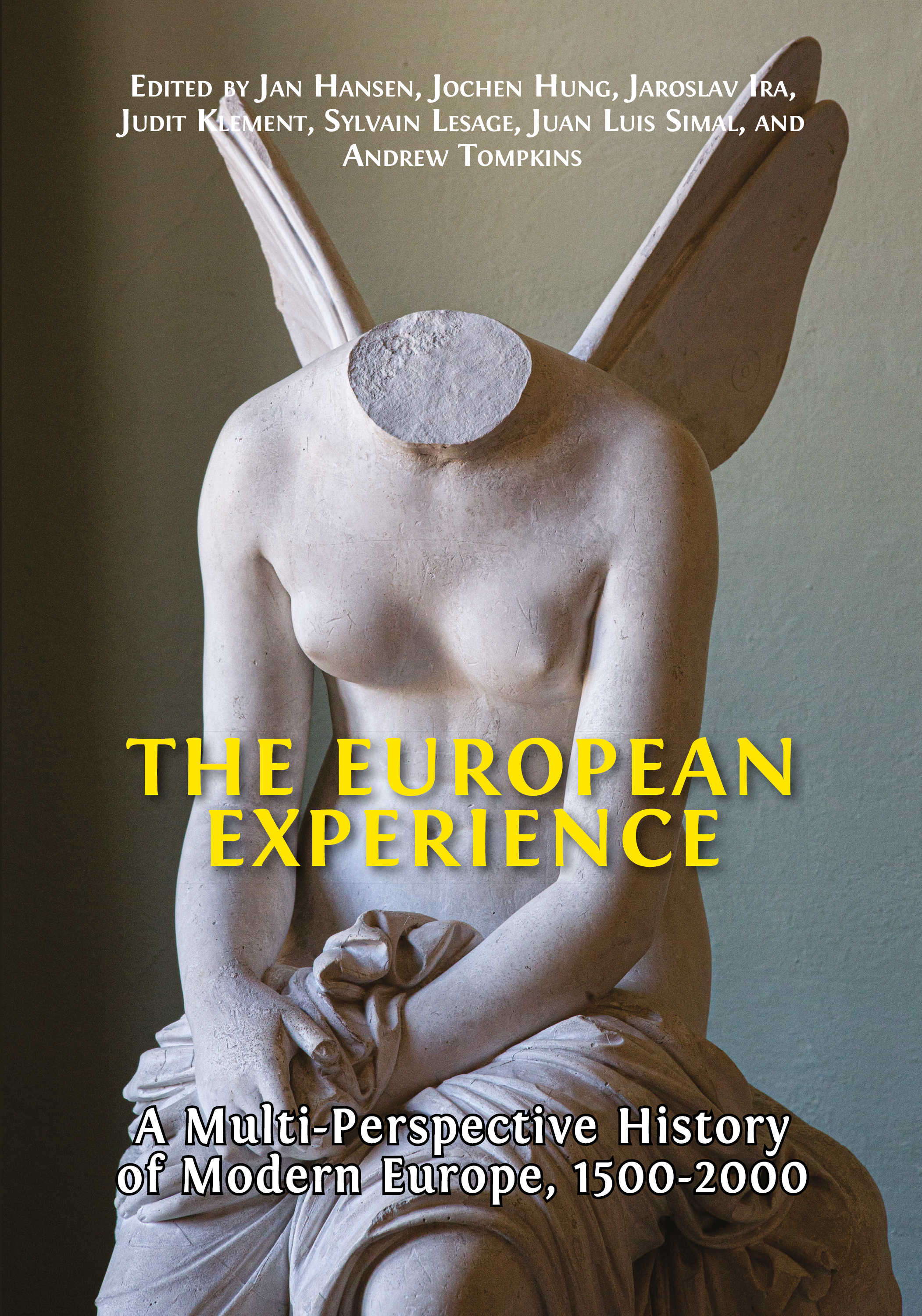

The chapters in this handbook are not intended to answer all of the questions that students might have about European history; on the contrary, they are meant as discussion starters, designed to complicate seemingly conclusive historical narratives and to generate class discussion. They should make students think and ask themselves which perspectives are missing from this collection of multiperspective histories, and which other approaches could be taken. The one, overarching lesson that all chapters intend to teach is that European history is always incomplete. This lesson is best expressed by this book’s cover image: a classical sculpture, located in Carrara, Italy, missing its head. The statue’s incompleteness not only reflects the double-sided nature of European history—civilisation and violence—but also it ambiguous, unfinished, and broken character. European history does not have a single vision or master narrative, but instead results from a complex interplay of forces that are best understood by drawing on multiple perspectives.

This handbook is one of the outputs of the Erasmus+ Strategic Partnership ‘Teaching European History in the 21st Century’ (TEH21), financed by the European Commission and running from 2019–2022. We are grateful for the support of the Dutch National Agencies Erasmus+ during this time, particularly during the difficult first months when we had to adapt the project to the challenges of the Covid-19 pandemic. Our project partner, the European Association of History Educators (Euroclio), gave us important feedback on the structure of this teaching resource and did invaluable work in making the knowledge of this handbook available to a broad public beyond academia.

There are many individuals who have helped to make this project a success and to whom we are deeply indebted. The members of our advisory board—Joanna Wojdon (University of Wroclaw), Simina Badica (House of European History, Brussels), and Oscar van Nooijen (International Baccalaureate Organization, Den Haag)—provided us with invaluable feedback and advice throughout this time. Justine Faure and Isabelle Surun (Université de Lille), Heike Wieters and Paul Treffenfeldt (Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin), and Martial Staub (University of Sheffield) helped us get the project off the ground and to establish it at their institutions. The project would not have run nearly as smoothly without the tireless work of our project secretary, Miranda Renders (Utrecht University).

This handbook is intended for undergraduate students in an international classroom. Over the course of the project, we invited several groups of students from all involved institutions to read and discuss selected chapters with a critical eye, and whenever this representative audience had the feeling that the scope, content or structure of this handbook did not serve its purpose, we went back to the drawing board. We are grateful for their time, enthusiasm, and critical engagement with our project. Most of all, we are thankful for the hard work by our colleagues all over Europe, under often extreme conditions. Their successful collaboration over three years, reconciling often very different academic cultures, working habits, school holidays, and ideas about history-writing, is the foundation of this truly European endeavour.

Bibliography

Aktionsrat Bildung, Internationalisierung der Hochschulen. Eine institutionelle Gesamtstrategie (Münster: Waxmann, 2012).

Levsen, Sonja and Jörg Requate, ‘Why Europe, Which Europe? Present Challenges and Future Avenues for Doing European History’, https://europedebate.hypotheses.org/86.

Taylor, A.J.P., Paul Dukes, Immanuel Wallerstein, Douglas Johnson, Marc Raeff and Eva Haraszti, ‘What is European History …?’, in What is History Today …? ed. by Juliet Gardiner (London: Palgrave, 1988), pp. 143–154, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-349-19161-1_13.

Vereniging Hogescholen [Netherlands Association of Universities of Applied Sciences] and Vereniging van Universiteiten [Association of Universities in the Netherlands] (VSNU), Internationalisation Agenda for Higher Education (14 May 2018), https://www.universiteitenvannederland.nl/files/documents/Internationalisation%20Agenda%20for%20Higher%20Education.pdf.

Wansink, Bjorn, Sanne Akkerman, Itzél Zuiker and Theo Wubbels, ‘Where Does Teaching Multiperspectivity in History Education Begin and End? An Analysis of the Uses of Temporality’, Theory & Research in Social Education 46:4 (2018), 495–527.