9.

Twin Peaks

© 2024 Stephen Tumino, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0324.09

In order to address the question why Twin Peaks is ‘happening again’ in 2017 after 25 years it is useful to consider why the melodramatic and campy murder mystery had such popular appeal — at least among the mostly white college educated audiences for whom the catchphrase ‘Who killed Laura Palmer?’ could be taken as a kind of cool and ironic riposte to the libertarian trope ‘Who is John Galt?’ — when it originally aired in 1990. To do that requires reading it against the socioeconomic and ideological background of the last quarter century.

The original series first aired during the early years of the neoliberal period of global capitalism heralded by neoconservative and Reagan administration functionary Francis Fukuyama as the ‘end of history’. What that meant in neoliberal sociology was the superiority of ‘free markets’ over the ideological driven politics of the past. What the end of the Cold War entailed for the former Soviet Union was a blueprint for what has since come to be known as the ‘shock doctrine’ (Klein): the use of a manufactured financial crisis as a thin justification for a kleptocratic elite to pillage public resources and carve up the USSR into warring neoliberal fiefdoms. In the US, the capitalist triumphalism launched a new imperialism of endless wars against external and internal ‘others’ (the drug war, the crack down on ‘illegal’ immigrants, union busting, the ‘war on terror’,… ) that was justified in the 90s under a pragmatic post-political Third Way approach to governance by ‘new democrats’ like Bill Clinton who presided over the dismantling of the ‘welfare state’ and the build up of the reigning warfare state. In cultural theory, class was no longer taken to be the operative division in society on the view that in the ‘knowledge economy’ all have equal access to ‘cultural capital’. Discourse theory dominated the academy and echoing Thatcher’s claim that ‘there is no such thing as society’ limited its analyses to the ‘micropolitics’ of everyday life on the argument that the universal ‘grand narratives’ of the past such as class struggle no longer compelled belief. Twin Peaks reflected its time. It presented the vision of a world in which material conflicts are resignified as cultural differences and inverts causal explanations into the undecidable play of endless interpretations.

On the surface, a murder mystery told with campy and melodramatic excess featuring the many off-beat and quirky characters that populate the small town of Twin Peaks, on another level, the show tells the noir-ish story of the ruthless Pacific Northwest border war between the Horne and Renault brothers over the drug trade and prostitution ring centered on the Canadian brothel One-Eyed Jack’s that included plans for the scrapping of the local lumber mill and destruction of forest preserves for the commercial development of the region. In most readings of the Lynchian universe, this doubling of the world is taken to be a critical gesture that defamiliarizes the cozy and quaint appearance of rural, small town America by exposing the seedy underworld of rape, incest, and sadistic criminality that sustains it. In this sense the story centers on how beneath the perfect facade of high school student and homecoming queen Laura Palmer, whom everyone thought they knew and loved, there lurked the terrible secret of traumatic rape and abuse at the hands of her father and the local business leaders who ruthlessly exploited her suffering. By its structure the show suggests that the multitudinous pleasures and tragicomic narratives that make up everyday life are but coping mechanisms that distract us from the true misanthropic horror of a world ruled by the alogic of patriarchal power and desire. Twin Peaks personifies its cynical double vision of the world in the gleeful visage of the otherworldly character of Killer BOB — ‘He is BOB, eager for fun. He wears a smile, everybody run!’ — the evil entity who, when he is not possessing Laura’s father Leland, takes on the appearance of a homeless indigenous man. More important than whatever doubtful and confused feminist message the show may seem to be telegraphing, however, is how its bifurcated narrative structure privatizes public explanations based on economic causes and limits intelligibility to the emotional and affective in the manner typical of melodrama, as Marx explained in his critique of Eugene Sue’s The Mysteries of Paris.379 Twin Peaks performed the ideological legitimation of the politics of neoliberal austerity by renarrating class antagonism as cultural differences, putting the thick description of endless cultural negotiations over meanings in place of root explanation of the social totality.

The ‘twinning’ of the world in Twin Peaks (from the eponymous ‘peaks’ themselves, to Laura’s two deaths, the White vs. the Black Lodge, doppelgängers, mirrors, ) represents the ‘negation of the negation’ of the material world by the spiritual. In other words, because the world produced by the triumph of global capitalism over actually-existing socialism is a class divided world and its appearance as a series of material conflicts gives the lie to all idealist interpretations and ideological justifications: such materialist knowing must be actively suppressed in public discourse. Twin Peaks serves this reactionary function by representing the social conflicts as the after effect of a spiritual division, if not exactly the good/evil dichotomy of Christian theology, whose tropes also feature in the show, then more so the division of the world between those who value ‘love’ (supported by the White Lodge) over ‘fear’ (the denizens of the Black Lodge), as more in line with the vedantic derived TM woo of the David Lynch Foundation. In short, in the original Twin Peaks, class does not divide people, values do.

Perhaps the most articulate reason for this inversion of material causes into spiritual ‘values’ given in the show is delivered by Annie, the ex-catholic nun and love interest of Agent Cooper in season 2, when in her acceptance speech for the crown of Miss Twin Peaks she proposes a spiritual solution to the corporate destruction of the environment by quoting Chief Seattle, the leader of the Suquamish tribe after whom the city is named,

‘Your dead [...] are soon forgotten and never return. Our dead never forget the beautiful world that gave them being’ […] We tell ourselves the world is not alive so that we won’t feel its pain. But instead we feel it all the more. Maybe saving a forest starts with preserving the little feelings that die inside us every day. Those parts of ourselves we deny. Because if that interior land is not honored, then neither will we honor the land we walk.380

In the world of Twin Peaks, the dead never really die (they go to the red lined Waiting Room) and their haunting of the living is a way to signal opposition to a dualistic materialist worldview held to be responsible for the deadening of the world. The ‘loving’ (those representing the ecological values of the White Lodge) interpret this mystification of the material into the ‘interior land of feelings’ as a ‘beautiful’ thing needing to be ‘preserved’ so as to overcome materialistic division by the embracing of difference as self-same. Those of the Black Lodge, on the other hand, like BOB and Windom Earle, the despised and dishonored in Annie’s discourse, who return to the living in order to feed on their ‘garmonbozia’ (pain and sorrow), have a different interpretation. As Windom Earle puts it

Once upon a time, there was a place of great goodness, called the White Lodge. Gentle fawns gamboled there amidst happy, laughing spirits. The sounds of innocence and joy filled the air. And when it rained, it rained sweet nectar that infused one’s heart with a desire to live life in truth and beauty. Generally speaking, a ghastly place, reeking of virtue’s sour smell. Engorged with the whispered prayers of kneeling mothers, mewling newborns, and fools, young and old, compelled to do good without reason [...] But, I am happy to point out that our story does not end in this wretched place of saccharine excess. For there’s another place, its opposite.381

Through this spiritual division Twin Peaks represents the world as a culture ‘clash of civilizations’ between rival interpretations of hegemonic capitalism that either imagine its negation as the absorbing of differences into the logic of the same (White Lodge) or promote the acceleration of its rapacious drive against any and all ideological limitations (Black Lodge). In either case it is a world without an ‘outside’ alternative to capitalism grounded in class and thus perfectly in line with the neoliberal ideology of the end of history.

The spiritualization of conflicts is clear in the opening credit sequence as well which opposes images of nature (robin, trees, waterfall) against industrial production (smokestack industry) which, significantly, appears to be completely automated. It encapsulates the depiction of a world without labor or class struggle where ‘values’ divide people. The ‘spiritual’ polarization of the world in Twin Peaks functions as a moral condemnation of the ‘externalities’ of capitalism that immunizes its root in exploited and alienated labor from materialist critique.

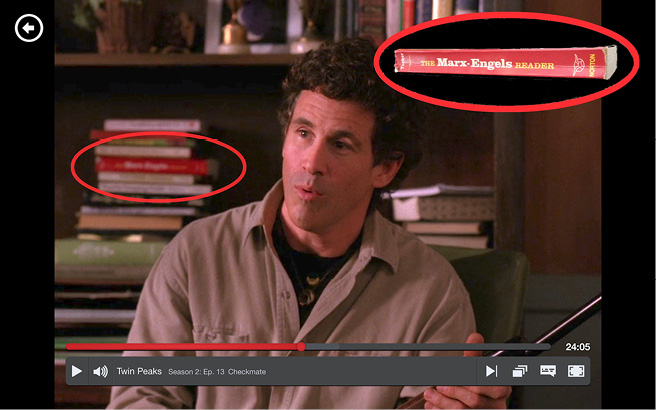

The nineties version of Twin Peaks is a post-racial allegory as well. Although it reproduces familiar stereotypes of people of color as ‘exotic’ (Josie, Hawk,…) and ‘violent’ (Killer BOB, Josie again,…) it renarrates race as merely cultural difference — the division of the world into ‘fearful’ vs. ‘loving’ types, Black (Lodge) against White (Lodge). The iconic black and white zig-zag pattern of the Waiting Room floor itself serves as an allegory of the color line in the US as a shifting slippery one open to playful reversals rather than a ruthless and oppressive binary. If this sounds like a stretch, consider that upon his first entry into the show at the end of season 2, Cooper confronts Jimmy Scott, the famous jazz vocalist playing the Black Lodge Performer, singing ‘Sycamore Trees’ (written by Lynch) in a haunting style that evokes Billie Holiday’s rendition of ‘Strange Fruit’, except in this version it’s the black man who tells the white man, ‘I’ll see you in the branches that blow, In the breeze, I’ll see you in the trees’. Then there is the ‘comedic’ subplot of season 2 in which Ben Horne, the hotel magnate/crime syndicate boss, becomes obsessed with the Confederacy, implying that because nostalgia for a racially polarized past is a coping mechanism for white anxiety in a world of cutthroat competition from ‘others’ (the Renault family), it should be indulged. The Bookhouse Boys club that local law enforcement forms to keep the ‘darkness of the woods’ at bay (shape-shifting beings like Killer BOB, played by the Native American actor Frank Silva), as well as to torture suspects, is another way that the show plays with racist tropes. It what may perhaps be a knowing wink of acknowledgment of the ludic cultural politics of the show, in much the same way as the soap opera Invitation to Love that plays in the background is a reflexive commentary on the show within the show, there is the subtle allusion to what appears to be a copy of The Marx-Engels Reader in Sheriff Truman’s office that suggests by its placement in the Bookhouse Boys library that ‘class’ is just white identity politics writ large to be taken as a sign of fear and resentment toward ‘others’ (see Fig 1).

Fig. 1. David Lynch, Twin Peaks (1990–1991), Viacom/CBS.

It is significant to the racial politics of the show that the Agent of the FBI Internal Affairs Unit to whom Cooper must turn over his badge in season 2 because he has violated FBI jurisdiction by crossing the Canadian border to save Audrey from the Renault crime syndicate is played by a black actor (Clarence Williams III). The Agent is, incidentally, the only black character in the entire original Twin Peaks universe who is not a demon from the Black Lodge (which on my count amounts to three). This is significant for the same reason that Dennis/Denise, the Special Agent who first appears in season 2 played by David Duchovny and returns as FBI Chief of Staff in season 3, is a transgender person. What is being suggested by the placing of culturally marginalized figures in positions of power is that race and gender are no longer divisive categories — even the bigoted Agent Rosenfield turns out really ‘loves everybody’ as he choses to live his life ‘in the company of Gandhi and King’ — but that the Law of the land is post-racial and post-sexist. And yet, Cooper’s disregard for the Law, not only in his roaming outside its geographic jurisdiction but with his ‘Tibetan method’ too that allows him to border cross into the spirit world and glean from his dreams and visions clues and insights into suspects’ characters, is yet another of the ways the story argues that it is necessary to violate the Law in order to save it. What makes Coop a hero we are being told is how even in his disregard for the Law, he preserves its spirit, in contrast to those who in their privileged bureaucratic complacency subvert its force. Cooper’s appearance in the town of Twin Peaks as an Agent of the Law explains why he is so often referred to by the townies as the foreign element causing the weird events that are besieging their homeland. At the same time, Cooper’s violations of the Law and his wish to join their gated community (most especially, the Bookhouse Boys) also suggests another unconscious reason for his golly-gee-whiz enthusiasm for the small town simplicity of Twin Peaks to begin with: ‘white flight’ from the big city overrun by overbearing PC multiculturalism. This may also explain why already upon his entry into Twin Peaks in the pilot episode he says to Diane that he would ‘rather be here than in Philadelphia’, where his Bureau office is stationed, which is where, as was revealed in the 1992 prequel to the show, Twin Peaks: Fire Walk with Me, we saw that he had recently had the disconcerting experience of encountering the border jumping Agent Phillip Jeffries (played by the gender bending David Bowie), with his ‘exotic’ shirt, inexplicably teleported in from Buenos Aires without a Law or wall in the world able to prevent it, questioning his identity (see Fig. 2). From the episode with Jeffries in the prequel which propels him to Twin Peaks, to his encounter with the androgynous Black Lodge Performer in the last episode of the original series, Cooper comes full circle, as can be seen by the same hurt and confused expression he wears in reaction to the same accusatory gesture that questions his sure sense of himself and renders him speechless and immobile (see Fig. 3). Cooper’s symbolic castration, represented by the flaccid and infantile Dougie Coop in season 3 (2017), functions in the same way as does the sacrifice of MIKE’s arm as a sign of his ‘goodness’ in contrast to a world given over to the mindless pursuit of narcissistic enjoyment represented by BOB. Cooper’s strange adventures in the spirit world give an inverted reflection of the multicultural landscape he must navigate as a white man that indicates and alludes to feelings of inadequacy and anxiety regarding the loss of his privilege. What the cultural politics of the original show normalized, however, was the repression of class from public awareness. What is signified in the new season in its very title, Twin Peaks: The Return, is the return of the repressed symbolized by the ghost army of blackfaced homeless men.

Fig. 2. ‘Who do you think that is there?’ David Lynch, Twin Peaks: Fire Walk with Me (1992), MK2 Éditions (France).

Fig. 3. David Lynch, Twin Peaks (1990–1991), Viacom/CBS.

Twin Peaks has returned to television after a quarter century when the domestic cost of the US’s endless wars in the form of inequality, austerity, and insecurity has embedded itself in the public consciousness while its economic causes remain a politically taboo topic foreclosed from public debate that displaces and distorts people’s anger and frustration onto ‘others’ (Muslims, Black Lives Matter, immigrants, Antifa, Russia, China,… ). Someone born after the ‘end of history’ would be coming of age now and not have experienced a world with any alternative to capitalism and its endless wars, nor even a radical critique capable of producing class-conscious explanations and solutions to the social immiseration and climate destruction produced by unfettered and borderless capital.

In line with the contemporary historical moment, Twin Peaks: The Return presents a much darker vision of the world. In stark contrast to the New-Age-y lifestyle politics of the original series, we find characters confronting their problems with a much more materialist mind set, as when Janey-E Jones, the suburban housewife played by Naomi Watts, dresses down the gangsters extorting her husband Dougie by informing them that, ‘We are not wealthy people. We drive cheap, terrible cars. We are the 99 percenters. And we are shit on enough. And we are certainly not gonna be shit on by the likes of you!’ Sure it’s opportunistic boilerplate not to be taken seriously — leaving aside the cliché rhetoric and melodramatic delivery, we know that he’s in debt because of gambling and that she’s trying to keep the bulk of her husband’s winnings — but still the discourses the show relies on register what has become the new populist common sense since the 2007–08 crash. Because the old ideological mechanisms for suppressing the centrality of class relations as the shaping determinant of capitalism no longer work, popular culture is forced to talk about class, but the way that it does relieves the pressure of class awareness on the common sense by representing class as ‘classy’, as lifestyle differences based on income and access to ‘cultural capital’ rather than the exploitation of labor. The blackfaced homeless horde that emerges in episode 8 of season 3 marks the equation of class with the possession of ‘cultural capital’ such that ‘lower’ class is signaled as the lack of whiteness, cleanliness, domesticity, privacy, individuality, etc.

Fig. 4. David Lynch, Twin Peaks (1990–1991), Viacom/CBS.

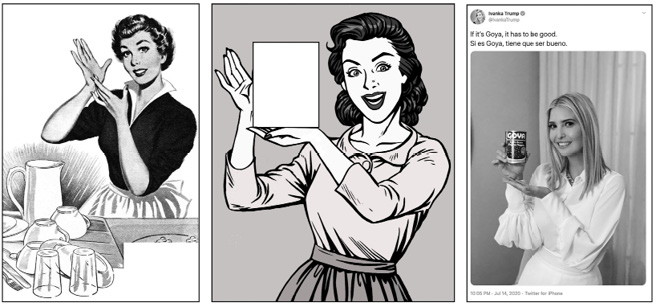

The show itself suggests an explanation for the new populist common sense in the way that the season premier of season 3 repeats the penultimate Waiting Room scene of season 2 which features the enigmatic gesture Laura Palmer presents to Cooper by way of characterizing the intervening quarter century (see Fig. 4). Although one interpretation of the gesture is that it is the mudra of ‘fearlessness’ found in Hindu and Buddhist iconography, this is perhaps more its prescriptive meaning for how the past 25 years ought to be dealt with, according to the spiritual ideology of the show’s creators, in contrast to its more descriptive meaning as a sign of the dominance of the market logic über alles, as suggested by its similarity to the commercial hand gesture of retro advertising (see Fig. 5). What the sequence suggests is that the ‘waiting room’ period of the ‘end of history’, the last quarter century dominated by neoliberal economics and culture wars, has in the meanwhile allowed the dark forces of ‘materialism’ to run rampant: materialism as mindless consumerism.

Fig. 5. Ivanka Trump. Instagram (14 July 2020).

If in its original iteration Twin Peaks presented the dark forces of the Black Lodge threatening to engulf the heartland of small town American values, today it depicts a world where the Black Lodge has most decisively triumphed, and the show now reveals the rapacious spirit of BOB to be a technologically wired and borderless power (moving from Las Vegas to Los Angeles, South Dakota to Buenos Aries), served by a reserve army of unemployed that New York City billionaires are seeking to harness through science (with the Glass Box device). What’s on TV is no longer a litany of saccharine soap operas but a toxically metastasized much more nasty, brutish, and Hobbesian version of Animal Planet lacking any trace of cultural value. The quirky local characters have been transformed too. Dr. Jacoby is no longer the pathetic hippie figure with a quaint out-of-date vision of free love, but has become Dr. Amp, the raving host of a conspiracy theory podcast denouncing global corporate dominance and climate destruction, while opportunistically hawking gold painted shovels to ‘dig yourself out of the shit and into the truth for only $29.99!’

In the meanwhile, Coop has transformed from the epitome of moral rectitude as FBI Special Agent Dale Cooper from season 1, to the more down to earth-toned sheriff’s deputy of season 2, to become a Chauncey Gardiner type character (Dougie) totally at the mercy of shrill, gold-digging, domineering women, such as his ‘wife’ Janey-E and Jade, the black sex worker Dougie frequents. The question is: Will Cooper be able to reassert the power of White Law and return to the real world to defeat the Black forces of materialistic desire and greed that have run rampant in the meanwhile (See Fig. 6)?

Fig. 6. David Lynch, Twin Peaks (1990–1991), Viacom/CBS.

In any case, beyond the surface difference of a shift from postmodern cultural politics to a new ‘materialist’ populist politics, what has not fundamentally changed in Twin Peaks: The Return is the basic way that the show performs the ideological function of occulting the class relations that alone explain the state of the world by projecting the cause onto demonic ‘others’ — a secret cabal of evildoers now represented by the ‘swarthy’ doppelgänger of Cooper himself.