‘April 1, 2021’

Created by Vanessa Dinh, Graphic Design Major, University of the Arts, Philadelphia, USA, CC BY 4.0

1. ‘Tag, You’ve Got Coronavirus!’Chase Games in a Covid Frame

© 2023, Julia Bishop, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0326.01

Touch chase is one of the oldest and most widespread forms of play in the childhood repertoire. It is elegantly simple in conception—the chaser role changes from one player to another when the latter is caught—yet amenable to adaptation in a myriad of ways. Its requirements are likewise simple—a defined space to move around in and more than one player, plus an agreement to chase or be chased according to rules agreed by the players to govern a particular game. These affordances have led to huge variety as well as the remarkable recurrence of certain forms and elements.1

Touch chase is often high on the list in surveys of games popular among children in the school playground during breaktimes (e.g. Blatchford, Creeser and Mooney 1990). Yet, there is generally little detail as to which children it is popular with and how frequently, in what forms and for what reasons chasing is played. Likewise, for such a universal kind of play, there are few in-depth or international studies. Part of many children’s everyday experience in middle childhood (around six to twelve years), touch chase often goes unnoticed by adults, although they might recognize having played it themselves as children, and may intervene if it leads to injury, conflict or aggression (Blatchford 1994).

At the time of the global spread of the novel coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 in early 2020, however, adults quickly became aware that children were incorporating elements into their play that related to what was happening in the wider world. Among the reports that started to crop up, especially on social media, were some which spoke of chase games with names like Coronavirus Tag, Corona Tip, Infection and Covid Tiggy. In these, the chaser was typically cast as the coronavirus, or as having Covid-19, and they had to chase the others and transmit it to them:

‘You got the Covid’ (Place unknown, 20 March 2021, Twitter)

‘CORONA CORONA!’ (Place unknown, 22 September 2021, Twitter)

‘Run he’s infected!’ (Place unknown, 5 November 2020, Twitter)

‘Tag you’ve got coronavirus!’ (Canada, 23 March 2020, Twitter)

Children were also adapting their chase games to circumvent or accommodate social distancing measures:

The students aren’t allowed to touch hands, so they’ve invented ‘corona rules’ for all their normal games. We’re about to play ‘corona rules mushroom tag’ and it involves a lot of elbows. (Australia, 19 March 2020, Twitter).

Adult responses varied. Some expressed sadness and pessimism at the emergence of coronavirus chasing games, some reacted with amusement, and others saw them as potentially dangerous, victimizing or inappropriate, on the one hand, or educational, therapeutic or creative on the other. Incongruity and bemusement were common. ‘Just heard that the kids at the local primary school were playing “Coronavirus Tag” this morning before bell. Not sure whether to laugh or cry’, tweeted a parent in the UK in March 2020. ‘It’s bizarre hearing 8 year olds asking their friends if they can play Corona’, posted a member of staff at a Swedish school nine months later.

This chapter examines accounts of coronavirus-related chase games gathered from scholarly research, news reports and social media posts for insights into how the games were played, by whom and in what countries and settings, how they came about and why, and how they relate to earlier chasing games. The focus is on any touch chase games which have been inflected by the Covid-19 pandemic in the way they were played, be this in terms of rules, roles, language and terminology, embodied practices, imagined scenarios, use of space and/or proxemics. Beneath the similar-sounding names are varied and dynamic games. As I have described elsewhere, there is thus not one coronavirus tag game but many (Bishop 2023). They emerged rapidly and in many places at once, continued to be reported for at least two years (although with dwindling frequency), and generally seem to have been the result of children’s own initiatives. Touch chase games relating to current affairs are not a new phenomenon (Eberle 2016), and neither are those relating to illness and affliction (e.g. Opie and Opie 1969: 75–78), but in the case of Covid-19, they are probably the most widely spread and extensively reported instances. They have the potential to shed light on children’s practices and experiences of chasing play, and highlight the importance of taking it seriously and considering its nuances.

Tracing Chasing in a Pandemic: Social Research and Social Media as Sources

Due to the conditions of the pandemic and the widespread and rapid emergence of the games, I have had to rely on others’ accounts, predominantly those of other adults, rather than direct observation of and research with children themselves. These comprise i) research projects documenting aspects of everyday life during the pandemic using online surveys and video call interviews, ii) journalists’ reports and iii) individuals’ posts on social media. Projects focusing specifically on children’s lives and play experiences include the ‘Play and Learning in the Early Years (PLEY) Covid-19 Survey in Ireland’ (discussed by Egan and others in Chapter 12), the ‘Pandemic Play Project in Australia’ (see McKinty and Hazleton 2022, and also Chapter 16 in the present volume) and the ‘Play Observatory’ in the UK (Cowan et al. 2021, and Potter and Cannon in Chapter 14).2 The news reports derive from the UK, Denmark and the USA (BBC 2020, Christian 2020, Smith 2020, Cray 2020, Hunter and Jaber 2020, Griffiths 2020). One drew on accounts garnered through an appeal made via the news outlet’s Facebook page for parents (Bologna 2020a, 2020b).

By far the most numerous reports of Coronavirus Tag appeared on Twitter, however. With over two million daily active users worldwide (Dean 2022), the platform is increasingly being used as a source of data in scholarly research (Ahmed 2021). In particular, it can provide real-time and ‘naturally occurring’ information on attitudes, responses and networks (Sloan and Quan-Haase 2017). Social media, including Twitter, were of particular importance during the pandemic as a source of information and means of conversation, especially during periods of social distancing and lockdown (Chen et al. 2020). It is not surprising that it has proved an important source for this study. Previously folklorists have focused on folklore as transmitted and created on social media and in digital communication (Blank 2012, De Seta 2020, Peck and Blank 2020). In this case, social media, and specifically Twitter, has been drawn on as a major source of information about children’s folklore taking place in face-to-face settings.

To locate ‘tweets’ (messages of up to 280 characters posted on Twitter) relating to Coronavirus Tag, I used the platform’s own advanced search function, employing such terms as ‘coronavirus’, ‘covid’, ‘corona’, ‘pandemic’, and ‘infection’ in various combinations with ‘tig’, ‘tiggy’, ‘tag’, ‘chase’, ‘playground’ and ‘game’. Twitter users can connect their content and make it more findable by tagging a keyword or topic with a hashtag (#) to link it to other tweets incorporating the same hashtag. I therefore searched on #coronavirustag, #coronatag, #covidtag, #covidgames, #pandemicplay and #pandemictag. A wide range of terms and some educated guesswork was required since the name of the game, and the way it is described and hashtagged, is variable. Further searches became necessary as new names and possible hashtags (such as #kidsarefunny corona) were discovered. Searches containing the term ‘tag’ returned many irrelevant results given the use of this term in a different sense within the platform itself.

Only tweets stating that a person had directly observed play, or were reporting first-hand testimony about it, were used. This resulted in 247 examples. Tweets are thus the source of approximately 75% of the 331 examples of coronavirus tag games assembled in total for this research. There are undoubtedly more to be uncovered and it should be noted that the resulting data is currently confined to English-language examples only.

There is currently considerable debate concerning the ethics of using Twitter data in academic research (Ahmed, Bath and Demartini 2017, Ahmed 2021). It is important to note that Twitter’s terms of service and privacy policy clearly state that tweets are in the public domain and users are able to restrict who has access to them if they wish. Users can also opt to be known by a pseudonym rather than their real name when they tweet. There are still ethical issues to consider, however, such as the lack of informed consent from users and the possibility that they could be identified (insofar as they have made themselves identifiable on the platform) from the words of their tweet, and whether this would cause them harm or put them at risk. There is also the difficulty of being able to sufficiently contextualize Twitter content and to obtain demographic profiles of those providing it (e.g. Fiesler and Proferes 2018; Sloan 2017). While it is theoretically possible to contact individuals via the platform to gain consent, this has proved difficult in practice. Not all have enabled direct messaging and, as described in a British Educational Research Association case study (Pennacchia 2019), the process proved complex and time-consuming, and had a patchy response.

The following approach to the use of Twitter data in this study has received ethical approval from the University of Sheffield, UK. Tweets have been harvested to provide details of children’s touch chase play in its many manifestations. The central focus is on the attributes of the game and those playing it (their age and gender), and when (date and time of day) and where (geographical location and specific setting) this was happening. The identity of the person tweeting is only of interest inasmuch as it sheds light on the context in which they have observed or heard about the game—as a teacher or parent, for example—and the context in which they may pass comment on it.

The tweets themselves are not consistent in mentioning the date and place of the game they describe so the date it was tweeted and the geographical location of the person tweeting have been taken as the next best clues. The date of the tweet is always clear but establishing a person’s location has generally meant consulting their personal profile to see whether they have included their location. For Twitter users to do so is optional, however, so it has not been possible to establish the location of the game in all cases. It is also possible that the location of the person tweeting is not the same as that where the game was being played.

Due to my focus on tweets as a source of information about children’s games rather than the person posting, and the minimal use of personal data, the risk of harm to those tweeting is judged to be low. I have therefore not attempted to seek consent from the individuals whose tweets I draw on. Instead, all tweets reproduced here are presented anonymously excluding the author’s Twitter handle and the tweet url. Geographical location, also potentially identifying, has been limited to country. Any tweets that reveal personal information about the children playing the game, such as their names, have been redacted, and any photographs and films of children included have not been used.

Nevertheless, quotations from tweets appearing below are mostly presented verbatim and as such could be traced on Twitter. Verbatim quotations are at the heart of much qualitative research, however, and in this case they contain details that would be difficult to paraphrase and it is important not to distort. The quoted examples have been selected with care and the status of all the tweets used in the study as in-the-moment conversational reports is fully acknowledged.

Data Overview

To date the number of examples of coronavirus tag games gathered from all sources combined is 331. The vast majority (roughly 97%) of these examples comprise adult observations of children and adult-reported children’s testimony.3 Many are necessarily brief and inevitably partial, omitting details that might seem mundane to an adult and instead tending to focus on the more striking aspects of the play. As a result, the accounts are uneven and there is no easy way to check the reliability of the information they contain. There is also minimal or no contextualization in terms of the players’ identities and the norms of play in that particular setting nor in wider socio-cultural terms. Even so, they are of significant value when taken together as an indicator of children’s experiences and provide unique insights into aspects of their everyday lives that would otherwise have gone undocumented. The corpus does contain a small amount of testimony gathered directly from children who have played coronavirus chase games, including first-hand audio-recorded accounts gathered as part of the Pandemic Play and the Play Observatory projects, and a number of these are drawn on below.

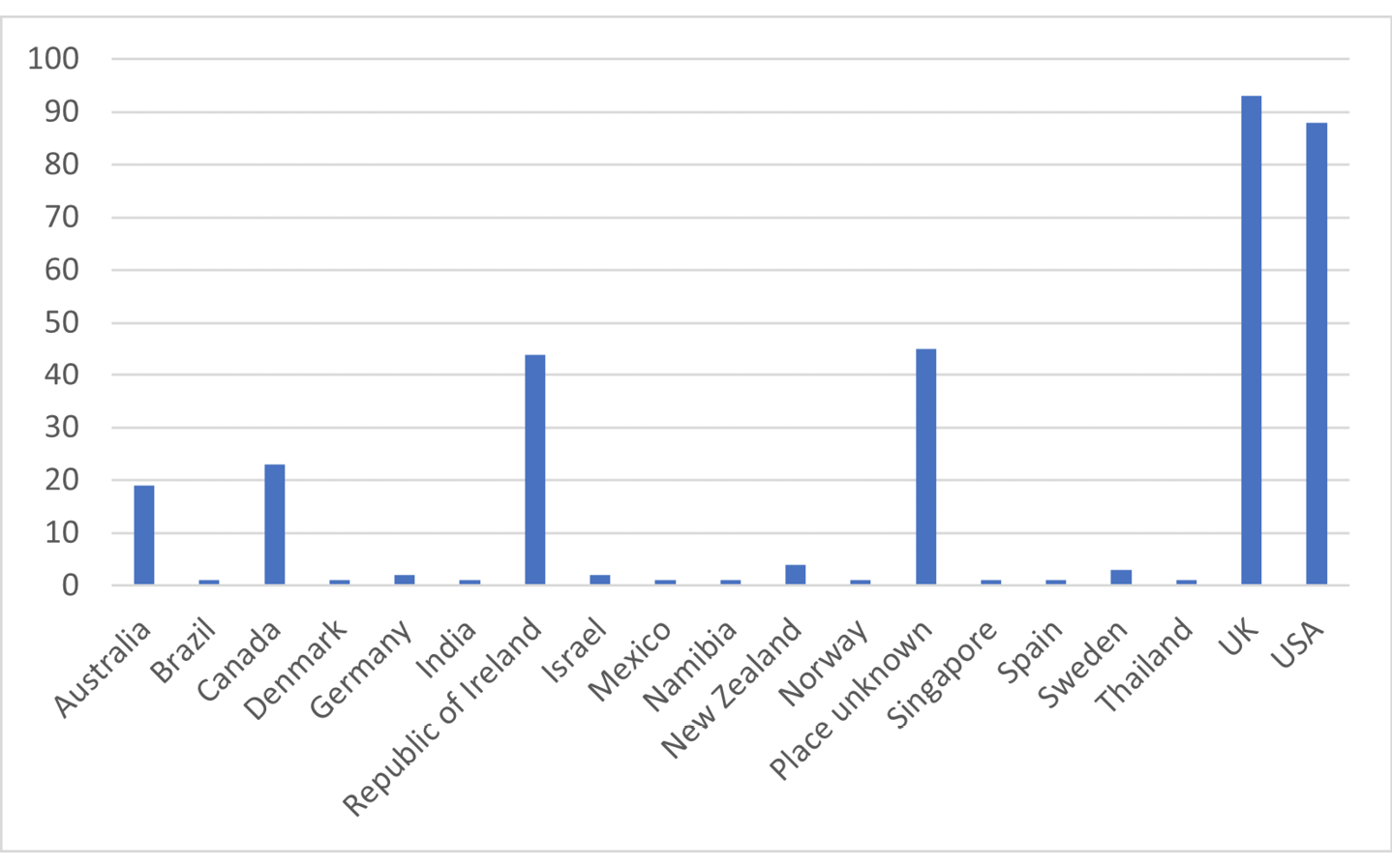

The overall corpus covers the period February 2020 to April 2022. The examples emanate from at least eighteen different countries, as far as it has been possible to ascertain their geographical provenance in the case of the Twitter data, as discussed above. Their geographical distribution is shown in (Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1 Instances of coronavirus tag games per country (Feb. 2020–Apr. 2022)

Created by Julia Bishop, CC BY-NC 4.0

Approximately 39% of the reports mention the age of the children involved and this ranges from three to eighteen years, sometimes as part of mixed-age groups, such as older and younger siblings, and sometimes including parents. The majority of ages mentioned (120 out of 149 instances) are in the range six to eleven years. There is likewise reference to gender in some of the accounts but this is generally in terms of the child from whom the information comes rather than an indicator of the composition of the group who were playing the game.

In terms of chronology the earliest reference to Coronavirus Tag so far discovered was reported in a tweet from Australia (4 February 2020):

Dropped the son at school. Boys playing tag. One yells: I’M CORONA VIRUS AND I’LL CATCH Y’ALL! Sad times.

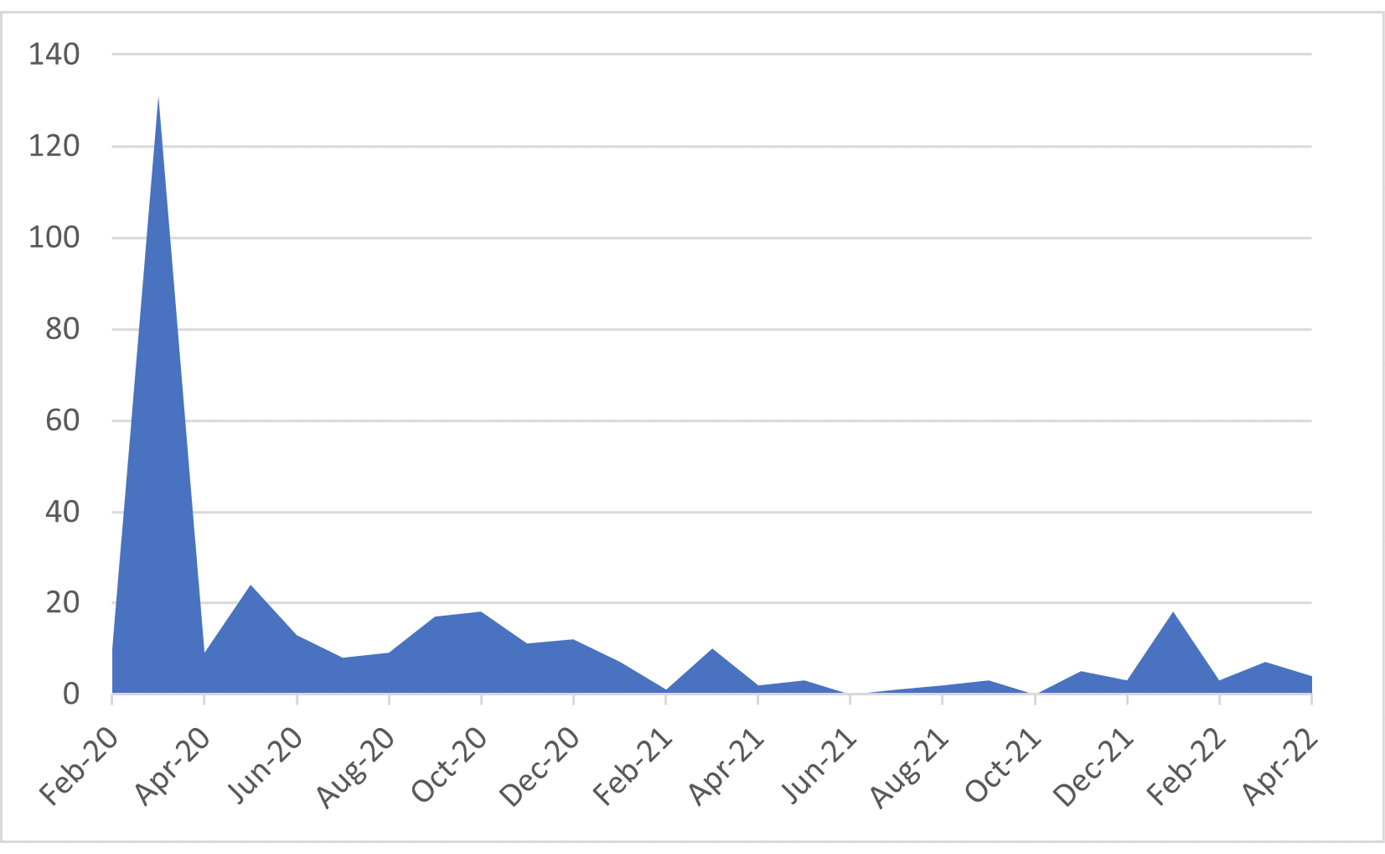

Further reports quickly followed on social media. Taken together with later accounts that date the playing of the game to this period, they evidence a huge surge in observations of coronavirus tag games in March 2020, comprising 131 instances or 39% of the total number of examples found over the 27-month period (Figure 1.2).

Figure 1.2 Instances of coronavirus tag games by date played

Created by Julia Bishop, CC BY-NC 4.0

In many countries represented by these tweets, this was immediately before schools were closed and just over half of the instances dated to March mention or imply school as the setting for these games, many explicitly referring to breaktime. The number may well be higher as a number of descriptions do not mention any setting. It seems reasonable to take the number of observations as indicative of a sudden craze for coronavirus chase games among children at this time. The number of instances then drops steeply but there are small increases in June and September 2020, March 2021 and January 2022 which may in turn be indicative of actual increases in the frequency of the game following children’s return(s) to school after further closures.

School is not the only setting of the games, however. Neighbourhood streets, parks and in the countryside are also mentioned, and gardens or backyards are implied in versions played on a trampoline. There is also an instance at an airport terminal, another at a swimming pool and an account by a ten-year-old of an attempt to adapt the game for playing remotely using mobile phones (Play Observatory PLCS3-20210702-at1 2023).

At school, the games were played among peers in the playground but during lockdowns, this changed to family members, often with siblings or cousins, sometimes parents, and occasionally other children in the neighbourhood.

From Coronavirus Tags to ‘Corona Rules’ Tags

1) Coronavirus Tags

Just as touch chase games in general are many and varied, so too are their coronavirus-related incarnations. The idea that the chaser personifies the virus or is infected with it is common to the vast majority. Within these, several types of game can be discerned depending on the way in which the role of the chaser is carried out and what happens to players who are caught, insofar as the accounts contain this information. These also suggest the immediate antecedents on which the players have drawn.

Successive chaser games of Coronavirus Tag, for example, resemble Plain Tag or Ordinary Tag in that the player who is caught immediately takes over the role of the chaser and the original chaser becomes one of the players trying to elude their touch, but cast in terms of contagion (‘Whomever was “it” had the virus and only got rid of it by tagging someone else’). Examples come from the USA, Canada, the UK and Israel, in some cases with further refinements, such as in the means of tagging another player (e.g. ‘you run after each other, and when you get a meter away, you clap—and then that person is it’, tweeted from Israel on 16 May 2020). Alternative ways of tagging are common and are discussed further below.

In cumulative chaser games, on the other hand, the person caught joins forces with the chaser so that the number of those chasing proliferates, as described by Griffin for the Pandemic Play Project:

Recording 1.3 Corona Tip and Corona Bullrush, Griffin, aged nine, Australia, 18 June 2020

To listen to this piece online scan the QR code or follow this link: https://soundcloud.com/user-661596830/griffin-9-corona-tip-and-corona-bullrush

Recorded by Mithra Cox, 2020, CC BY-NC-ND 4.04

These games are variations of games sometimes known in Australia respectively as Build up Tips and Bullrush (for pre-pandemic examples, see the Childhood, Tradition and Change project website, 2011). Again, there are accounts of similar coronavirus chase games from Ireland, the UK, the USA and Canada. In the Canadian example, the proliferating chasers must also hold hands which ‘was against the school protocol but it was fun’ (9 October 2020, Twitter).

A further form of coronavirus tag games involves the elimination of those caught, either temporarily or for the rest of the game. A tweet from Germany recounts that ‘one child plays the #SuperSpreader and has to tag the others. The winner is the one who hasn’t been tagged’ (24 September 2020). Elsewhere, it is said that the players so caught may be impounded or ‘die’ unless they can tag someone else within a certain timescale (such as ‘if you were tagged, you had 20 seconds to tag someone else or you were “dead”‘, reported in a tweet from the USA on 10 March 2020), giving games similarities to those with cumulative chasers. In another example, from the UK, the players ‘have to be locked in “the zone”—that’s the climbing frame at the school playground—for the rest of lunchtime with no human rights’ (BBC 2020). There are shades here of the jail in Cops and Robbers where players may remain for the rest of the game or be able to be released by players who are still free (Roud 2010: 32). The reference to human rights may echo concerns raised in relation to restrictions introduced during the pandemic (e.g. Amnesty International 2020).

Ways in which tagged players can be untagged or ‘released’, thereby delaying or overturning the transfer of the chaser role, represent one of the most creative parts of coronavirus tag games. Sometimes the onus is on the player who has been caught (e.g. ‘if you’re tagged you have 5 seconds to get to the vaccine house (hut) otherwise you have it too’, reported a UK tweet on 28 November 2020) but more commonly it is up to another player. Not surprisingly, medical care or the receiving of a ‘vaccine’ is a common scenario in coronavirus tag games and is accomplished by a whole range of gestural, verbal, spatial and material means:

1 player is the virus. Virus tags people with elbow. Once tagged must get vaccine within 10 seconds or joins virus tag team. 2 other players are doctors who give vaccine (untag person with elbow). If doctor tags original virus player, the game is over. Doctor then becomes the virus or take turns (Place unknown, 10 September 2020, Twitter)

Kids in Brazil have started playing a new variation on tag called COVID. One kid is coronavirus and has to tag the others to infect them, while another is an ambulance and has to drag tagged players to a marked space, the “hospital”, to get them back in the game (Brazil, 15 March 2022, Twitter)

Some children in Australia ruled that ‘if you shout “vaccinated” it’s the equivalent of having a forcefield but only lasts 6 seconds’ (4 September 2021, Twitter). Sometimes a prop is involved, such as a pen or balloon pump, by which the players pretend to administer the injection.

Many adults saw connections between the coronavirus games they witnessed and the well-known game of Stuck in the Mud or Freeze Tag:

One person is COVID. If they tag you, you have to freeze in place. Another person is the vaccine who runs around unfreezing people by tapping them twice, ‘because you need two shots!’ (USA, 13 January 2022, Twitter)

It’s basically ‘stuck in the mud’ but when you tag someone you have to shout ‘isolate’ and you free someone by tapping them while shouting ‘vaccinate’ (UK, 18 January 2022, Twitter)

A UK example contributed to the Play Observatory described ‘lots of playing stuck in the mud as the coronavirus in school during bubble playtime. Pretend hand wash sets you free’ (Play Observatory PL186A1/S004/d1 2023). This appears to be an adaptation of Toilet Tig in which the free player pushes down on the outstretched arm of the player who has been caught, simulating flushing (cf. Roud 2010: 21). In the coronavirus tag version, the same or similar gesture presumably suggested the action of the pump on a soap dispenser bottle.

Other ways of releasing tagged players appear directly inspired by current affairs:

P3s [6- to 7-year-olds] have apparently worked out the rules for coronavirus tig. One is it, all folks tagged also become it. If you get tagged by someone without ‘the coronavirus touch’ and manage to sing Happy Birthday twice, you’re free. Tagged by the ‘touch’ mid song? Start again.

Tweeted from the UK on 4 March 2020, this was just three days after public health announcements urging people to wash their hands for at least twenty seconds, accompanied by ministers’ colourful advice to gauge the time by singing the song ‘Happy Birthday’ twice through (Bloom 2020). This in turn prompted a wave of popular humour, including internet memes and alternative song suggestions as well as this ingenious tag game.

Another UK example that contained an echo of current affairs ruled that if players were ‘tagged with “Tory” they’re not allowed to eat until someone tags them with “Rashford”‘. This refers to the campaign by Manchester United footballer Marcus Rashford for the government to provide meal vouchers for children in poorer families over the summer break of 2020 (BBC Newsround 2020).

Temporary immunity from being caught also featured in coronavirus tag games. Surprisingly, pretending to wear a mask, for instance by putting a hand or sleeve to one’s face, was infrequently reported, maybe because this would have been too easy a way of evading being tagged. Instead, there were more traditional methods, such as sitting with crossed legs (Australia), and getting ‘off-ground’ (given a pandemic twist in a UK tweet on 5 March 2020 stating, ‘The benches are doctors. You can’t be virused there’). Nevertheless, public health measures in the US presumably inspired one game in which ‘you can stop someone tagging you by yelling “Clorox” [a brand of bleach]’ (3 April 2020, USA, Twitter).

2) ‘Corona Rules’ Tags

As the name suggests, the idea of a significant touch is central to games of touch chase for ‘a touch with the tip of the finger is enough to transform a player’s part in the game’, not only from chased to chaser but also from tagged player to freed one (Opie and Opie 1969: 62, 64). Yet, a number of tweets from the UK, USA and Australia mention that children are not allowed to touch hands at school or in some cases touch each other at all. This does not seem to have been official advice as such for schools which, at the outset in the UK at least, stressed hand and respiratory hygiene, disinfection, ventilation and managing potential cases (Department for Education 2020). It does seem to have been a practical way of trying to reduce close physical contact between children in educational settings, including at playtime. Such rules had significant implications for children’s everyday play practices and friendships in general (see Carter, Chapter 9 in this volume, and Larivière‐Bastien et al. 2022). In the case of chase games, the restrictions threatened their very basis and the possibility of playing them at all and there are a few reports of them being shut down or completely banned.

Likewise, physical distancing measures led to changes to breaktime routines and play space. This resulted in fewer outside breaks for some, and staggered playtimes for others. Several UK child contributors to the Play Observatory spoke of their experience of this at primary school on their return to school in September 2020. Ten-year-old Louis described how the staggered playtimes meant that he was separated from his friends (from whom he had already been isolated during the first UK lockdown) because they were in another class (Play Observatory PLCS1-20210603-at1 2023). Others described how the physical division of school playgrounds also led to separation from peers (Play Observatory PLCS10-20211208-at1 2023). Space in which to run around was consequently more limited and this in turn meant that tag games were not viable because ‘the space didn’t let you play it’ (Play Observatory PLCS8-20211125-at1 2023).

Children responded to these physical and temporal constraints in schools with a number of gestural and spatial variations in the way they played tag games in general, whether or not they were playing games involving a coronavirus chaser. Many were children’s own initiatives (e.g. Griffiths 2020). A common example was the introduction of the rule that coming within a certain distance of others, usually one or two metres, was the equivalent of tagging them, the transfer sometimes being marked by a shout or clap. Others avoided touching by using their elbow to tag people or throwing a ball or equivalent object at them, echoing previously well documented games such as Ball Tig and Dodgeball which operate on the same principle (Opies 1969: 73–74, Roud 2020: 35–36). Similar games were among those that took place at home during lockdowns with siblings. In cases where children had access to a trampoline, for example, they developed games such as Dodge the Virus which used a sensory ball that resembled images of the coronavirus (Beresin 2020: 275). Shadow tag, another older game (Douglas 1916, Opie and Opie 1969: 86) in which the chaser has to stand on another’s shadow in order to tag them, also made a comeback, sometimes led by teachers (e.g. Play Observatory PLCS7-20211029-at1 2023), but only playable on a sunny day.

Commended by adults, who sometimes supplied foam ‘noodles’ (normally used in swimming pool games) as another means of playing ‘no-touch tag’, these games and modifications were not always considered particularly effective by children in practice. Covid Tig is ‘rubbish’, commented one eight-year-old boy, because ‘no-one can agree what 2 metres is’ (20 October 2020, UK, Twitter) and a thirteen-year-old explained that ‘Shadow tig is really easy to cheat at. All you say is, “You weren’t standing on my shadow. You were standing on your own shadow. Doesn’t count. You have to be fully standing on my shadow” (Play Observatory PLCS3-20210702-at1 2023). Compliance with social distancing measures could thus cause ambiguity in a game and lead to frustration or disagreement.

At the other extreme, there are a number of reports in which children are described as breathing, sneezing, spitting or coughing on players to avoid tagging them by touch:

Long chat with year six [ten- to eleven-year-olds] about behaviour, hygiene etc. Fifteen mins later coronavirus IT was going on. Run after someone and cough on them and they are IT. (UK, pre-23 March 2020, Twitter)

These accounts suggest that some children deliberately adopted a more challenging or oppositional response to the imposition of social distancing rules, and have parallels in examples where children are reported as breaking the ‘no touch’ rules:

Took 8 yo to the playground thinking some outside play would be ok. The other kids made up a new kind of tag called Corona Virus Tag. You not only have to touch the other kid but hold them for 10 seconds “to let the germs spread.” (20 March 2020, Canada, Twitter)

We should exercise caution, however. Reports may be exaggerated or children’s actions misunderstood. There are also descriptions, for example, in which coughing is said to be intended as a sign of having been tagged:

If you are caught you have to cough as you now have COVID! (UK, 18 March 2021, Twitter)

or of being the tagger:

The one who’s it keeps coughing and the rest of them running around yelling oh no coronavirus!!! (Canada, 15 March 2020, Twitter).

The practice of coughing may still be regarded as risky under the circumstances but the intention may be realism (enhancing the chaser role) or pragmatism (identifying those tagged) and not necessarily malice or dissent.

Functions of Coronavirus Tag Games

A number of social media posts and journalist reports of Coronavirus Tag offer the interpretation that these games enable children to ‘process’ or ‘make sense of’ events in their lives or specifically that they are a means of playing out anxieties about the pandemic (e.g. Christian 2020). In this approach, coronavirus tag games are interpreted in terms of the pandemic. The following section attempts to turn things around and explore ways in which creating and playing the various coronavirus tags may have functioned for children as a way of keeping the pandemic in view but trying to centre children’s own experiences and perceptions of play. Functions identified include amusement, maintenance of social interaction and friendship with peers in the face of public health restrictions, intensified emotional expression and escape, risk-taking, the expression of dissent, a means of discrimination against individuals and groups, and stimulus to innovation, humour and re-creation. They are not intended as an exhaustive list and, with little direct testimony from children or contextual information, they can only suggest possible multiple and varying functions from the players’ points of view.

Pre-pandemic research by Howard et al. found that children ‘show a great deal of emotional attachment to play, feeling happy, sometimes elated, while playing[,] and a host of negative emotions when not able to play’ and when left out of play (2017: 387). Children’s emotional responses to coronavirus tag games, where reported, are likewise predominantly described as fun, enjoyable and a favourite activity, associated with laughter, pleasure, and shouting, screaming and yelling. There are few direct reports of negative responses, the main one being disapproval of games breaking social distancing rules. In this sense, coronavirus tag games were no different from any other games in children’s repertoires, in that they were often valued as an opportunity to express their identities and emotions freely, and to escape from everyday reality (Howard et al. 2017).

As described above, there is some evidence that children began to adapt the rules of their chase games as soon as social distancing measures were introduced at school so that they could continue playing a favoured game despite the constraints. The need for ‘corona rules’ helps to account for the huge surge in reports of coronavirus tag games—with a new name to distinguish them from the established ones—in March 2020 as these measures were first being brought in. Thus, a function of re-creating and playing these games for children was to allow them to continue engaging in something akin to one of their established practices of social interaction with their peers. Given that play of all kinds has an important role in supporting the development and maintenance of children’s friendships (Blatchford 1998), this may have become even more important when children returned to school en masse following periods of separation from their peers, accounting for persistent reports of coronavirus tag games beyond the initial surge. For similar reasons, they were also potentially important for those children who for various reasons continued to attend school during lockdowns and found themselves mixing with new classmates and mixed-age groups.

The need to accommodate distancing measures posed the potentially enjoyable challenge of finding substitutes for touch and spatial proximity. Not all children wanted to engage with these possibilities, however, some finding the alternatives limited, and some opting to play other games instead at this time, such as ones which needed less space and did not involve tagging people (e.g. Play Observatory PLCS10-20211208-at1 2023).

Other children apparently set out to challenge and resist constraints by deliberately invoking taboo actions and subverting or breaking the restrictions. In these cases, the games provided a means of dissent as well as an expression of bravado.

What comes through particularly strongly in the data, however, is not just the need to adapt touch chase games to accommodate and resist restrictions on physical contact and proximity. Rather, it is the way in which, for children, the pandemic opened up possibilities for reimagining their existing repertoire of games by furnishing a common set of cultural resources. Identifying the chaser with the coronavirus or Covid led to all kinds of innovations which, even while other resources (such as playground equipment) were limited, acted as a catalyst for creativity and experimentation. These functioned to alleviate everyday routine and possible boredom, bringing about a sense of novelty to, and ownership over, the outcome. If correct, this represents another possible reason for the huge surge in games evident in the March 2020 reports and, with unfolding of events as the pandemic progressed, suggests that the pandemic was a continuing source of inspiration for some time after.

The personification of the coronavirus and inclusion of scenarios suggested by current affairs also introduces a socio-dramatic element to touch chase, allowing for play-acting the parts of being scared and being scary, as in Monster Tag games more generally. The fact that coronavirus was a real life threat, however, potentially intensified the thrill of the game and heightened the ‘phantasmagoric’ dimension of this play (Sutton-Smith 1997). This created a context in which shouting, yelling and screaming were permitted. Thus the games allowed the exploration not only of fear but also of power, an opportunity to let go of inhibitions which, as Howard et al. found, children value in their play (2017: 384), and to be ‘larger (louder?) than life’, an exaggerated version of themselves (see Beresin, Chapter 17 for an extended discussion of exaggeration in online play).

Another function of children’s incorporation of verbal, gestural, material, behavioural, spatial and proxemic elements associated with the pandemic into their touch chase games was the creation of incongruities through which they could exercise their wit and ingenuity. This can be seen as a form of ‘quoting’, in the widest sense and in multimodal terms. In this process, as Finnegan identifies, the ‘far and near’ are held in productive tension with each other:

The distancing [involved in quoting another] in turn draws the quoted voice and text near, seizing and judging it: standing back not just to externalise but to claim the right to hold an attitude to it, whether of approval, caution, admiration, disavowal, analysis, interpretation, irony, reference…

[…] Quoting in its infinity of manifestations is at once ‘there and away’ and ‘here and now’. It is both to distinguish the words and voices [and embodied communication] of others and to make them our own, both distancing and claiming. (2011: 263)

Thus, in coronavirus chase games, children made opportunities for experimentation, redefinition, inversion, humour, mockery and resistance which not only ‘made sense’ of the pandemic—and the adult world’s response it—but nonsense.

Pre-pandemic research into children’s play has also highlighted the ambiguity of play and its potential to exclude and stigmatize certain players. McDonnell’s study of play narratives, for example, quotes a child as saying, ‘I had loads of friends but they’re not my friends because they’re running from me… He said “AAAAH run from him!’’’ (2019: 260). It is easy to see how coronavirus tag games have similar potential to stigmatize, isolate and disempower by casting the chaser as contagious and manoeuvring them into an unwitting or unwanted chaser role. The data contains a handful of examples in which this was, or may have been, the case and these are all based on racialized conceptions of the pandemic and its provenance:

Students were playing a game called coronavirus tag which was targeted towards Asian students. (USA, 16 February 2020, Twitter)

Racialized verbal and physical attacks involving people of all ages were certainly documented during the pandemic (see, for example, Human Rights Watch 2020). The brevity and decontextualization of reports of these instances that took place within touch chase games makes them difficult to examine critically and the paucity of evidence likewise makes it hard to gauge how widespread such practices were. It is nonetheless essential to acknowledge this potential in chasing play, which can easily be overlooked or dismissed as ‘only a game’ by adults and so go unchallenged (McDonnell 2019: 259–60).

‘Topical’ Tags and ‘Contaminating Games’ in Historical Perspective

Topical Tags

Children’s reframing of elements drawn from global flows of information or ‘mediascapes’ (Appadurai 1990) in their play has a long history (for an overview, see Marsh 2014). Mediascapes provide ‘large and complex repertoires of images, narratives and “ethnoscapes” to viewers throughout the world, in which the world of commodities and the world of “news” and politics is profoundly mixed’ (Appadurai 1990: 299). Characters and associated plot elements drawn from popular culture and news may thus be introduced into touch chase games. These may be generic, as in Cops and Robbers with their associated ‘jail’, and Witches and Fairies with their cauldron or stewpot, or specific to the latest television series, films and storybooks (Roud 2010: 18–19; for a storybook example, see British Library 2011).

An example of this is the emergence of zombie-related tag games. These show the influence of the modern zombie figure and the zombie apocalypse trope found in books, comics, films, cartoons and videogames (Conrich 2015). They seem to have become popular, at least in the UK, in the 2010s (e.g. Willett 2015; Bishop 2023). In popular culture, the zombie figure is often associated with the concept of a deadly virus, those infected then becoming zombies themselves whose proliferation threatens, in terms of the trope, to overrun the world. The humans pitted against them must avoid infection in order to survive. These scenarios have obvious parallels with both cumulative and elimination tags, and indeed tag games with names relating to zombies and infection are often reported as taking these forms (see, for example, Holben 2020). Zombie and infection names, together with Build Ups names (noted above in Australia and also found in my own fieldwork at a Yorkshire primary school in 2010 and 2018) and Family Tig (Roud 2010: 20), appear to have superseded earlier names for proliferating chaser games, such as Help Chase and All Man He (Opie and Opie 1969: 89). Even in the mid-twentieth century, however, children in Fulham in West London reported playing Gorilla, in which ‘immediately one is court [caught] he becomes a goriller with the original one’, again suggesting the influence of films and comics of that time (quoted in Opie and Opie 1969: 89).

Thus, children may re-create any form of tag game to make it topical by imbuing the chaser and chased roles, and sometimes other roles besides, with characterizations inspired by contemporary mediascapes. In addition, they may update existing topical tags in similar fashion. This is exactly what seems to have happened during the pandemic. The personified coronavirus or Covid-infected chaser turned games such as Stuck in the Mud into topical tags, with knock-on refinements as described above. Likewise, games called Covid Zombies and Zombie Tag Coronavirus emerged, some cumulative or eliminatory in form—‘once tagged you become an infected walking zombie’, reported a tweet from Ireland in October 2020, ‘game continues to last child standing who restarts the game’. Infection Tag, meanwhile, rapidly took on a new resonance, alarming to adults, even without a modification of its name:

“Parenting in the Age of Coronavirus”

A one-act play by me and my kid

Kid: “At recess, we played this fun game called Infection”

Me: “THAT SOUNDS VERY DANGEROUS YOU SHOULD NOT PLAY THAT”

Kid: “Mama, calm down, it’s basically tag”

Me: *dies of anxiety anyway*

FIN (26 Feb 2020, USA, Twitter).

Next we briefly consider ‘contaminating games’ before considering the relationship between topical tags and contaminating games.

Contaminating Games

Coronavirus tag also belongs to a class of games in which the chaser’s touch has a ‘noxious effect’ (Opie and Opie 1969: 75). Childlore researchers Iona and Peter Opie dubbed these ‘contaminating games’, commenting:

Chasing games could well be termed ‘contaminating games’ were it not that the children themselves do not, on the whole, think of the chaser’s touch as being strange or contagious. Their pleasure in chasing games seems to lie simply in the exercise and excitement of chasing and being chased; and the contagious element, which possibly had significance in the past, is today uppermost in their minds only in some unpleasant aberrations, which are here relegated to a subsection. (1969: 62)

In the Opies’ experience, such forms were the exception rather than the rule among children in mid-twentieth-century Britain. They comprise games in which the chaser has a disease, affliction or undesirable personal characteristic which is transmitted to another player by their touch. These include games involving the fictitious Lurgy and Aggie Touch, disease-related games such as Germ, the Plague and Fever, and undesirable person forms, such as Lodgers and the [Person’s name] Touch (1969: 75–78). The Opies stress that during the game, and even after it, ‘the suspension of disbelief in the game’s pretence can be absolute: the feeling is unfeigned that the chaser’s touch is unhealthy’ (1969: 77).

Touch chase games of this kind have been documented in many countries of the world. The Opies cite examples from New Zealand, Spain and Italy, as well as a nineteenth-century example from Madagascar in which the chaser was known as bôka, ‘a leper’ (1969: 77). The most extensively studied and enduring contaminating game is Cooties, a form particularly widespread in America where it dates from at least the 1930s and ‘40s (Knapp and Knapp 1973; cf. Bronner 2011: 213–17). Cooties are a fictitious undesirable affliction, transmitted through touch or physical proximity, often from a member of the opposite sex. The main way of ridding oneself of them is to pass them on to someone else. This can be done surreptitiously or can be more overt, giving rise to Cooties Tag (Samuelson 1980).

In the second half of the twentieth century and into the twenty-first, there has been a whole catalogue of disease-related chase games, memories (but few details) of which were prompted by social media posts about Coronavirus Tag. These not only included AIDS Tag (cf. Goldstein 2004: 1–3) but also Ebola, MERS, Swine Flu Edition [Tag], TB and Polio.

There have also been newer incarnations of imaginary afflictions, such as the Cheese Touch—made famous (and topical) in Jeff Kinney’s book Diary of a Wimpy Kid (2007), and spinoff film (2010)—and Virus (Roud 2010: 32), in which the touch of a particular person is rendered undesirable. Both of these games appear to have been used as starting points by children for the development of coronavirus tag games. A tweet from Australia, for example, described a game of Coronavirus Tiggy played at school which ‘consisted of getting touched with “virus cheese.” If you get “virus cheese” by being tagged, you become “infected” and you have to chase others in the game’ (18 March 2020). Similarly, ten-year-old Louis, interviewed for the Play Observatory project, explained how the game of Virus played with his friends became Coronavirus Infection, a topical tag and contaminating game relating to the pandemic:

It is not difficult to see how games of noxious touch can be used to stigmatize and isolate individuals deemed undesirable or unpopular. Yet, in the case of Louis and his friends, the game appears to be experienced in a good-natured way. This also seems to be true of the majority of examples gathered for this research, although this is by no means certain, for we lack the voices of those who played them and the specifics of how they were played.

What makes the difference between contaminating games experienced as good-natured and those intended and/or experienced as discriminating and excluding? It is not possible to do justice to this question here. Contaminating games are complex and, every time they are played, the outcome is subject to a range of factors: the nature of the players’ relationships with each other, the nature of the disease, characteristic or affliction around which they are framed (which, like Cooties, may be shifting and ambiguous), and social structures and discourses around otherness and inequality by which they are informed.

The tone of contaminating games and the way they are experienced by players is also affected by the form that they take. The games of noxious touch, as described by children to the Opies, are successive chaser games. The possibility of singling out an individual is greater in these as only one person is the source of contamination at a time and the game is basically one person against all. If there is a release element too, then the solidarity of those tagged with those remaining free is reinforced and the chaser is more isolated in terms of the game. For a strong chaser whose social status within the group is reasonably assured and equal, this may be a welcome challenge but for a weaker player and/or one whose status is unequal, ambiguous and not assured, the power dynamics inherent in the game may be experienced very differently. In cumulative chaser games, on the other hand, those tagged swap sides so it is the chaser who receives assistance and who becomes less isolated, provided they can catch another in the first place. In the elimination form, one person is again pitted against all the other players but their kudos grows as they catch others and they can progress to the status of ‘winner’ when all other players are ‘out’.

It is only possible to distinguish the form of the game definitively in thirty-three of the coronavirus tag game examples gathered for this study but, of those, it is notable that twenty-seven are cumulative or eliminating. Given the power dynamics inherent in the different forms of tag games, it would be interesting to know if this is indicative of a more general increase in the popularity of cumulative and eliminating games of tag from the time of the Opies’ research in the third quarter of the twentieth century to now.

Conclusion

Coronavirus Tag has been shown to be a wide range of games in practice, ingeniously imbued with an array of details gleaned from, and inspired by, mediascapes as well as necessitated by local conditions. Many of these emerged at speed in many different places more or less simultaneously in the early days of the pandemic in the Global North and particularly at times when children were at school together. It has been possible to see parallels and antecedents which fostered the games’ creation, their widespread occurrence and their variety. Just as American folklorist Herbert Halpert argued in relation to traditional song—that ‘the presence or absence of parodies or local songs is a test of the vitality of a folk song tradition. If singers do not make up new songs, or manipulate the old materials, we have one indication that the singing tradition in that area has become fossilised’ (1951: 40)—we can see the creation of coronavirus tag games as indicative of the contemporary vitality of touch chase play more generally among children.

As we have seen, the games take a number of different basic forms—successive, cumulative and eliminatory—and may embed mechanisms of release and immunity. I have argued that the form of the game adopted by the players is an important determinant of its potential and actual power dynamics which in turn impacts on players’ experiences of the various roles and rules. I have also sketched a range of potential functions for coronavirus tag games for further investigation, research in which the participation of players themselves is crucial. The suggested functions attempt to foreground their experiences and are intended to acknowledge the possibility of multiple functions, rather than a priori and universalizing ones which may prioritize adults’ sensibilities over those of the players. A historical and comparative perspective has shed light on the ambiguities of the game, its continuities with the past in terms of topical and contaminating elements, but also the differences of its specifics and its meanings in the contemporary context.

It is fully acknowledged that this study has relied almost entirely on adult testimony and that the majority of accounts are highly abbreviated. It nonetheless shows the interest and importance of sampling children’s play repertoires on a regular basis, preferably on the basis of observation and children’s own testimony, to understand everyday practices in play and peer interaction, their sensitivity to current affairs and wider discourses, including as shaped by contemporary mediascapes, and to detect changes over time and in space.

In this case, a comparative focus has helped to highlight that what children did in making their games of coronavirus tag is in fact just one example of what they do on a day-to-day basis when there is no pandemic. Children are in perpetual counterpoint with each other and the adult world and express this in their play, including their chase games. Coronavirus Tag drew adults’ attention to these processes and led to their documentation but also gave the impression that this was something special to the pandemic. World affairs and the mediascape never stop furnishing many other possibilities for topical play, such as the widely acclaimed South Korean series Squid Game on Netflix (Sharma 2021) and possibly the Russian invasion of Ukraine in February 2022. There are important insights to be gained from looking at the detail of play—to try and do justice to its variety, its responsiveness to catalysts both global and local, and the experiences of the people who are its architects. This in turn will add nuance to our understandings of children’s social lives and expressive culture, and the synergies between the two.

Works Cited

Ahmed, Wasim. 2021. ‘Using Twitter as a Data Source: An Overview of Social Media Research Tools’, https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/impactofsocialsciences/2021/05/18/using-twitter-as-a-data-source-an-overview-of-social-media-research-tools-2021/

Ahmed, Wasim, Peter A. Bath, and Gianluca Demartini. 2017. ‘Using Twitter as a Data Source: An Overview of Ethical, Legal, and Methodological Challenges’, in The Ethics of Online Research: Volume 2, ed. by Kandy Woodfield (Bingley, UK: Emerald), pp. 79–107, https://doi.org/10.1108/S2398-601820180000002004

Amnesty International. 2020. ‘Explainer: Seven Ways the Coronavirus Affects Human Rights’, https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2020/02/explainer-seven-ways-the-coronavirus-affects-human-rights/

Appadurai, Arjun. 1990. ‘Disjuncture and Difference in the Global Cultural Economy’, Theory, Culture & Society, 7: 295–310, https://doi.org/10.1177/026327690007002017

BBC News. 2020. ‘Coronavirus Outbreak: How Are Children Responding?’ Global News Podcast, 2 March, https://www.bbc.co.uk/sounds/play/p0856tth

BBC Newsround. 2020. ‘Marcus Rashford Forces Government U-turn after Food Voucher Campaign’, 16 June, https://www.bbc.co.uk/newsround/53061952

Beresin, Anna. 2020. ‘Playful Introduction to 9.3’, International Journal of Play, 9: 275–76, https://doi.org/10.1080/21594937.2020.1805967

Bishop, Julia. 2023. ‘Recreation and Re-creation in Children’s Pandemic Chasing Games’, in Creativity during Covid Lockdowns, ed. by Patricia Lysaght, David Shankland and James H. Grayson (Canon Pyon, UK: Sean Kingston)

Blatchford, Peter. 1994. ‘Research on Children’s School Playground Behaviour in the United Kingdom: A Review’, in Breaktime and the School, ed. by Peter Blatchford and Sonia Sharp (London: Routledge), pp. 15–35

——. 1998. Social Life in School: Pupils’ Experience of Breaktime and Recess from 7 to 16 Years (London: Falmer Press)

Blatchford, Peter, Rosemary Creeser, and Ann Mooney. 1990. ‘Playground Games and Playtime: The Children’s View’, Educational Research, 32: 163–74, https://doi.org/10.1080/0013188900320301

Blank, Trevor J. (ed.). 2012. Folk Culture in the Digital Age: The Emergent Dynamics of Human Interaction (Logan: Utah State University Press)

Bloom, Dan. 2020. ‘Coronavirus: UK government Tells Children to Sing Happy Birthday while Washing Hands’, Mirror, 1 March, https://www.mirror.co.uk/news/politics/coronavirus-uk-government-tells-children-21608374

Bologna, Caroline. 2020a. ‘35 Tweets about Parenting in the Age of Coronavirus’, HuffPost, 10 March, https://www.huffingtonpost.co.uk/entry/coronavirus-parenting-tweets_l_5e66af39c5b605572809d9bf

——. 2020b. ‘Coronavirus Tag? The Pandemic Has Become Part of Kids’ Playtime’, HuffPost, 12 March, https://www.huffingtonpost.co.uk/entry/coronavirus-tag-kids-playtime_l_5e680a01c5b6670e7300297e

British Library. 2011. ‘Jack Frost and Sally Sunshine’ [video], https://www.bl.uk/collection-items/jack-frost-and-sally-sunshine

Bronner, Simon J. 1988. American Children’s Folklore (Little Rock, AR: August House)

——. 2011. Explaining Traditions: Folk Behavior in Modern Culture (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky)

Burghardt, G.M. 2005. The Genesis of Animal Play: Testing the Limits (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press)

Burn, Andrew. 2014. ‘Children’s Playground Games in the New Media Age’, in Children’s Games in the New Media Age: Childlore, Media and the Playground, ed. by Andrew Burn and Chris Richards (Farnham: Ashgate), pp. 1–30

Chen, Emily, Kristina Lerman, and Emilio Ferrara. 2020. ‘Tracking Social Media Discourse About the COVID-19 Pandemic: Development of a Public Coronavirus Twitter Data Set JMIR Public Health Surveillance’, 6, https://doi.org/10.2196/19273

Childhood, Tradition and Change [Australia]. 2011, https://ctac.esrc.unimelb.edu.au/index.html

Christian, Bonnie. 2020. ‘Children Playing “Coronavirus” Game in UK Playgrounds, Mother Says’, Evening Standard, 2 March, https://www.standard.co.uk/news/uk/coronavirus-game-in-uk-playgrounds-a4376506.html#comments-area

Conrich, Ian. 2015. ‘An Infected Population: Zombie Culture and the Modern Monstrous’, in The Zombie Renaissance in Popular Culture, ed. by Laura Hubner, Marcus Leaning, and Paul Manning (London: Palgrave Macmillan), pp. 16–25, https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137276506_2

Cowan, Kate, et al. 2021. ‘Children’s Digital Play during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Insights from the Play Observatory’, Journal of e-Learning and Knowledge Society, 17: 8–17, https://doi.org/10.20368/1971-8829/1135590

Cram, David, Jeffrey L. Forgeng, and Dorothy Johnston. 2003. Francis Willughby’s Book of Games: A Seventeenth-Century Treatise on Sports, Games and Pastimes (London: Routledge)

Cray, Kate. 2020. ‘How the Coronavirus Is Influencing Children’s Play’, Atlantic, 1 April, https://www.theatlantic.com/family/archive/2020/04/coronavirus-tag-and-other-games-kids-play-during-a-pandemic/609253/

De Seta, Gabriele. 2020. ‘Digital Folklore’ in Second International Handbook of Internet Research, ed. by Jeremy Hunsinger, Matthew M. Allen and Lisbeth Klastrup (Dordrecht: Springer), pp. 167–83, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-024-1555-1_36

Dean, Brian. 2022. ‘How Many People Use Twitter in 2022? [New Twitter Stats]’, https://backlinko.com/twitter-users

Department for Education. 2020. Actions for Schools during the Coronavirus Outbreak https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/actions-for-schools-during-the-coronavirus-outbreak

Douglas, Norman. 1916. London Street Games (London: St Catherine Press)

Eberle, Scott G. 2016. ‘Trump Tag: Playing Politics on the Playground’, Psychology Today, 31 May, https://www.psychologytoday.com/gb/blog/play-in-mind/201605/trump-tag

Fiesler, Casey, and Nicholas Proferes. 2018. ‘“Participant” Perceptions of Twitter Research Ethics’, Social Media + Society, 4: 1–14, https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305118763366

Finnegan, Ruth. 2011. Why Do We Quote? The Culture and History of Quotation (Cambridge: Open Book Publishers), https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0012

Goldstein, Diane E. 2004. Once Upon a Virus: AIDS Legends and Vernacular Risk Perception (Logan: Utah State University Press)

Gomme, Alice B. 1984 [1894, 1898]. The Traditional Games of England, Scotland, and Ireland (London: Thames & Hudson)

Griffiths, Sian. 2020. ‘Children Let Off Steam with Covid Games’. Times, 6 December, https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/children-let-off-steam-with-covid-games-nkwnlccg9

Holben, Henry. 2020. ‘A Letter to COVID’, Milligan University Digital Repository COVID-19 Collection, http://hdl.handle.net/11558/5097

Howard, Justine, et al. 2017. ‘Play in Middle Childhood: Everyday Play Behaviour and Associated Emotions’, Children & Society, 31: 378–89, https://doi.org/10.1111/chso.12208

Human Rights Watch. 2020. Covid-19 Fueling Anti-Asian Racism and Xenophobia Worldwide, 12 May, https://www.hrw.org/news/2020/05/12/covid-19-fueling-anti-asian-racism-and-xenophobia-worldwide

Hunter, Molly, and Ziad Jaber. 2020. ‘Touch a Shadow, “You’re it!”: New Routines as Denmark Returns to School after Coronavirus Lockdown’, NBC News, 26 April, https://www.nbcnews.com/news/world/touch-shadow-you-re-it-new-routines-denmark-returns-school-n1192611

Knapp, Mary, and Herbert Knapp. 1973. ‘Tradition and Change in American Playground Language’, Journal of American Folklore 86: 131–41

——. 1976. One Potato, Two Potato: The Folklore of American Children (New York: Norton)

Larivière‐Bastien, Danaë, et al. 2022. ‘Children’s Perspectives on Friendships and Socialization during the COVID‐19 Pandemic: A Qualitative Approach’, Child: Care, Health and Development, 48, 1017–030, https://

Marsh, Jackie. 2014. ‘Media, Popular Culture and Play’, in The SAGE Handbook of Play and Learning in Early Childhood, ed. by Liz Brooker, Mindy Blaise and Susan Edwards (London: SAGE), pp. 403–14, https://dx.doi.org/10.4135/9781473907850.n34

McDonnell, Susan. 2019. ‘Nonsense and Possibility: Ambiguity, Rupture and Reproduction in Children’s Play/ful Narratives’, Children’s Geographies, 17: 251–65, https://doi.org/10.1080/14733285.2018.1492701

McKinty, Judy, and Ruth Hazleton. 2022. ‘The Pandemic Play Project: Documenting Kids’ Culture during COVID-19’, International Journal of Play, 11: 12–33, https://doi.org/10.1080/21594937.2022.2042940

Newell, William Wells 1963 [1903]. Games and Songs of American Children, 2nd edn (New York: Dover)

Opie, Iona, and Opie, Peter. 1969. Children’s Games in Street and Playground (Oxford: Clarendon Press)

Peck, Andrew, and Trevor J. Blank. 2020. Folklore and Social Media (Logan: Utah State University Press)

Pennacchia, Jodie (ed.). 2019. BERA Research Ethics Case Studies, 1: Twitter, Data Collection and Informed Consent (London: British Educational Research Association), https://www.bera.ac.uk/publication/twitter-data-collection-informed-consent

Play Observatory PL186A1/S004/d1. 2023. https://doi.org/10.15131/shef.data.21198142

Play Observatory PLCS1-20210603-at1. 2023. Louis (10 years) amd Jonathan (parent), interviewed by John Potter and Kate Cowan, 3 June 2021, https://doi.org/10.15131/shef.data.22012898

Play Observatory, PLCS3-20210702-at1. 2023. X1 (13 years) and X2 (10 years), interviewed by John Potter and Kate Cowan, 2 July 2021, https://doi.org/10.15131/shef.data.22012898

Play Observatory PLCS7-20211029-at1. 2023. Beatrice (pseudonym) (7 years) and Olivia (parent), interviewed by John Potter and Kate Cowan, 29 October 2021, https://doi.org/10.15131/shef.data.22012898

Play Observatory PLCS8-20211125-at1. 2023. Eli (7 years) and Rachel (parent), interviewed by John Potter and Julia Bishop, 25 November 2021, https://doi.org/10.15131/shef.data.22012898

Play Observatory PLCS10-20211208-at1. 2023. Harry (12 years), interviewed by John Potter and Michelle Cannon, 8 December 2021, https://doi.org/10.15131/shef.data.22012898

Roud, Steve. 2010. The Lore of the Playground: One Hundred Years of Children’s Games, Rhymes and Traditions (London: Random House)

Samuelson, Sue. 1980. ‘The Cooties Complex’, Western Folklore, 39: 198–210, https://doi.org/10.2307/1499801

Sandseter, Ellen Beate Hansen, and Rasmus Kleppe. 2019. ‘Outdoor Risky Play’, in Encyclopedia on Early Childhood Development, ed. by Richard E. Tremblay, Michel Boivin, Ray DeV. Peters, https://www.child-encyclopedia.com/outdoor-play/according-experts/outdoor-risky-play

Schwartzman, Helen B. 1978. Transformations: The Anthropology of Children’s Play (New York: Plenum Press)

Sharma, Ruchira. 2021. ‘Squid Game: Why You Should Not Panic about Reports Children Are Copying the Games from the Netflix Series’, iNews, 13 October, https://inews.co.uk/news/squid-game-games-netflix-series-challenges-reports-children-copying-warning-explained-1246173

Sloan, Luke. 2017. ‘Social Science “Lite”? Deriving Demographic Proxies’, in The SAGE Handbook of Social Media Research Methods, ed. by Luke Sloan and Anabel Quan-Haase (London: SAGE), pp. 90–104

Sloan, Luke, and Anabel Quan-Haase (eds). 2017. The SAGE Handbook of Social Media Research Methods (London: SAGE)

Smith, Mary. 2020. Letter, Guardian, 4 March, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/mar/04/childrens-games-are-going-viral

Sutton-Smith, Brian. 1972 [1959] ‘The Games of New Zealand Children’, in The Folkgames of Children, American Folklore Society Bibliographical and Special Series, 24 (Austin: University of Texas Press), pp. 5–257

——. 1997. The Ambiguity of Play (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press)

Virtanen, L. 1978. Children’s Lore. Studia Fennica, 22 (Helsinki: Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Suera [Finnish Literature Society])

Willett, Rebekah. 2015. ‘Everyday Game Design on a School Playground: Children as Bricoleurs’, International Journal of Play, 4: 32–44, https://doi.org/10.1080/21594937.2015.1017305

1 An international survey and bibliography of touch chase is lacking but one of the earliest references in the English language occurs in Francis Willughby’s Book of Games, compiled in the 1660s (Cram, Forgeng and Johnston 2003), and variants have been documented continuously from the nineteenth century on (see, for example, Gomme 1984 [1894, 1898]; Newell 1963 [1903]; Sutton-Smith 1972 [1959]; Opie and Opie 1969; Knapp and Knapp 1976; Virtanen 1978; Schwartzman 1978; Bronner 1988; Roud 2010). For animal chase games involving role reversal, see Burghardt 2005.

2 I am grateful to Suzanne Egan and Judy McKinty, Ruth Hazleton and Danni von der Borch for making their data available to me and clarifying details. Sincere thanks to my colleagues on the Play Observatory project (2020–2022)—John Potter, Kate Cowan and Michelle Potter at the Institute of Education, University College London (UCL), Yinka Olusoga and Catherine Bannister at the School of Education, University of Sheffield, and Valerio Signorelli at the Bartlett Centre for Advanced Spatial Analysis at UCL—for their support of my ongoing research into Coronavirus Tag.

3 Twitter’s terms of service allow users aged 13 years and over but the content of coronavirus tag tweets makes it clear they were being posted by adults.

4 Special thanks to Griffin and and Mithra for permission to include this audio clip in this chapter, and to Judy McKinty of the Pandemic Play Project for facilitating this.