10. Digital Heroes of the Imagination:An Exploration of Disabled-led Play in England During the Covid-19 Pandemic

© 2023, William Renel and Jessica Thom, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0326.10

Introduction

Since March 2020, more than 170,000 people in Britain have lost their lives to Covid-19. Of this total, approximately sixty percent have been disabled people, with learning disabled people being disproportionately affected (Bosworth et al. 2021; Public Health England 2020; Office for National Statistics 2022). Abrams and Abbott suggest that to adopt a disability studies perspective on Covid-19 is ‘to ask about who we treat as essential workers in our society, who we deem worthy of valuable resources, who has value, and, ultimately, what sorts of people we deem as worthy of living in the world’ (2020: 172). Between April 2020 and August 2020 seven international disability rights organizations worked together to produce the Covid-19 Disability Rights Monitor (Brennan 2020), surveying disabled people from across 134 countries. The research concluded that the pandemic has had a monumental impact on disabled people worldwide, due to inadequate measures to protect disabled people in health and social care settings, prioritization of normative bodies and minds, and a total breakdown of community services and support. The Disability Rights Monitor also highlighted the disproportionate impact of the pandemic for specific disabled people, including people of colour, those in rural areas, and children and young people.

Disability and Play

Much of the existing literature surrounding disabled children and young people and play has been developed through a medical model understanding of disability. This model frames disabled people’s experiences through an individualized perspective where impairments should be fixed or treated. The medical model dehumanizes disabled bodies and minds and has engendered a problematic history of disability and play focused on assessment, diagnosis and intervention. For example, ‘difficulties in sharing imaginative play’ is still used in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (American Psychiatric Association 2013) as a criterion for diagnosing Autism Spectrum Disorder. Porter, Hernandez-Reif and Jessee (2008) note that many disabled children and young people are made to undertake ‘play therapy’ where a trained adult professional will use play practices to help a disabled child or young person ‘to cope’. Methodologically, much of the existing literature relating to disabled children and young people’s experiences of play uses comparative studies between disabled and non-disabled participants (Brodin 2005; Messier, Ferland, and Majnemer 2008), surveys of parents or siblings (Stillianesis et al. 2021; Mitchell and Lashewicz 2018; Conn and Drew 2017) and interventions that seek to ‘teach’ disabled children how to play like their non-disabled peers (Jahr, Eldevik and Eikeseth 2000). In recent years there are a growing number of social and critical framings of disability and childhood studies where social, cultural and political contexts are given priority over individualistic and medical perspectives. Goodley and Runswick‐Cole (2010) led this call for a social turn in disability and childhood studies, contending that disabled children and young people’s play has too often been characterized as a tool for diagnosis and therapy, and arguing for the emancipation of play from the domains of assessment and intervention for disabled children. The social model of childhood disability (Connors and Stalker 2007) renews existing conceptions of the sociology of childhood (Prout and James 1997) by incorporating the social (Oliver 1990) and social relational models of disability (Reeve 2012; Thomas 2003). Collectively these perspectives provide a crucial opposition to existing medical framings of disability and play. Burke and Claughton suggest that by understanding the intersecting social, cultural and political complexities of disability and play, disabled children and young people become ‘active, creative agents who self-monitor, make choices and exert control over their play within unique play cultures that they construct for and between themselves’ (2019: 1078).

Disability, Play and Covid-19

UNESCO described Covid-19 as a global crisis for teaching and learning with 826 million children and young people (50% of learners worldwide) without access to a household computer and 706 million (43%) without household internet (UNESCO 2020a). Disabled children and young people were amongst the most at risk from disengaging from meaningful social, learning and play opportunities during the pandemic (UNESCO 2020b; UNICEF 2020). Sabatello, Landes and McDonald (2020) argue that the true impact of Covid-19 on the experiences of disabled people remains unknown as they continue to be under-represented in impact studies due to inaccessible data collection methods. Research that has focused on disabled children and young people shows that Covid-19 created significant reductions in physical activity and play opportunities (Graber et al. 2021; Moore et al. 2021; de Lannoy 2020) alongside increases in screen time and digital media use (Manganello 2021), increases in medication (Masi 2021) and a generalized decline in mental health and wellbeing (Cacioppo et al. 2021). In the UK, research during the pandemic highlighted that the impacts of Covid-19 would not be equally distributed and were likely to widen existing inequalities (Tonkin and Whitaker 2021; Public Health Scotland 2021). In addition, pandemic-related school closures created a significant increase in the use of information and communication technologies and remote learning environments (Zarzycka et al. 2021; UNESCO 2021). Remote learning via digital platforms offers some advantages to disabled children and young people due to increased flexibility with timings, opportunities to work in different locations, access to multimodal content and different modes of interaction (Bruce et al. 2013). However, remote working can also accentuate the existing digital divide (Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development 2001) and can only be effective when delivered alongside the appropriate infrastructure (e.g. access to wifi and electricity), accessible content (e.g. captions on videos, easy-read versions of written information), training and regular evaluation (Hashey and Stahl 2014; Chambers, Varoglu, and Kasinskaite-Buddeberg 2016). Although the foregrounding of digital play would undoubtedly work well for many children and young people, Casey and McKendrick note ‘that digital play is not equally accessible to all, notably, children from low-income families, disabled children, children with additional support needs, and refugee and migrant children’ (2022: 9).

Digital Heroes of the Imagination

In response to the significantly increased barriers to meaningful inclusive play opportunities for many disabled young people outlined above, Touretteshero partnered with the National Youth Theatre (NYT) to design and deliver a new, radical, disabled-led play project called ‘Digital Heroes of the Imagination’ (DHOTI). Touretteshero is a disabled and neurodivergent-led community interest company. Touretteshero’s mission is to create an inclusive and socially just world for disabled and non-disabled people through our cultural practice (www.touretteshero.com/). NYT is a pioneering youth arts organization that empowers young people. Since 1956, NYT has engaged over 150,000 young people and reached an audience of over two billion people across the world (www.nyt.org.uk). DHOTI was the first formal partnership between Touretteshero and NYT. The project builds on previous inclusive play projects that Touretteshero has designed and delivered across the UK since 2010. At the start of the Covid-19 pandemic, Touretteshero, a disabled-led company with clinically vulnerable staff, had to make a series of difficult decisions about what work we would continue to undertake. DHOTI was one of the few creative projects that Touretteshero delivered during the pandemic. The reason we decided to prioritize this project was our feeling that meaningful inclusive play opportunities would be more significant than ever for disabled young people navigating the complexities of the pandemic. With this in mind, DHOTI builds on what Lloyd (2008) describes as equitable experiences of education—those which disrupt normative creative and learning cultures towards approaches focused on inclusion and imagination. DHOTI combines inclusive practice training for young creatives, the distribution of accessible creative resources to learning disabled young people and hybrid digital-physical play sessions for disabled young people. Between June 2020 and January 2021 two phases of DHOTI were delivered, working in partnership with special educational needs or disabilities (SEND) schools in London. The following sections of this chapter will describe the two phases of DHOTI and the core elements of the project. By detailing these elements we hope to position disabled children and young people’s experiences at the centre of new discourses concerning play during the Covid-19 pandemic.

Phase 1—Pilot

The initial iteration of DHOTI was a small-scale pilot project, working with twenty-four disabled young people aged between eleven and nineteen from two classes at a SEND school in South London. The young people had a range of both physical and cognitive impairments as well as different communication preferences. Each of the students had an education, health and care (EHC) plan.1 During the pilot phase of DHOTI the UK was in full lockdown, meaning that the project would be delivered using digital technology within people’s home environments. Thirteen young people aged fourteen to twenty-five were recruited by NYT to become ‘makers’ and ‘creative buddies’ for the project. All of these young people received inclusive practice training from Touretteshero. The makers created all of the materials necessary for the project, these were collated in ‘top secret’ superhero kits which were delivered to the students’ homes by Touretteshero—the world’s first fully-fledged Tourettes superhero (Figure 10.1). The creative buddies partnered with young disabled people from the school and worked through an inclusive creative process collaboratively exploring four activity areas over two three-hour workshops.

Figure 10.1 Touretteshero Delivering ‘Top Secret’ Superhero Kits in South London during the Covid-19 Pandemic, July 2020

Photo © Touretteshero CIC, 2023, all rights reserved

Through the workshops, each of the young disabled students had opportunities to transform themselves into a new superhero, designing masks, capes and logos and creating new superhero powers and moves. The students also utilized the materials to transform their home environments into imaginative places where the superheroes could live, work and play. These included treehouses, urban cities, underwater kingdoms and intergalactic ships in outer space. The workshops culminated in short recorded videos where each of the superheroes showcased their new identities and shared their messages with the world. These included ‘Mr Healthy’ who helps people eat fruit and vegetables, ‘Dancing Isobel’ who makes people happy, and ‘Super Mermaid’ who rescues people that fall in the water. The majority of the messages that the superheroes created during the pilot phases reflected the context of the pandemic and the UK being in a full lockdown. Key themes included being outdoors, accessing nature, helping others and connecting with neighbours. Some of the messages that the students shared transcended the realities of the students’ day-to-day lives, such as ‘I have lion powers and I can walk through walls’. Other messages were self-reflective and related to the lived experiences of the students, such as ‘my superpower is drawing; it helps me calm down’. Some students used spoken words and Makaton2 to share their messages whilst others used text-to-speech devices.

Inclusive Practice Training

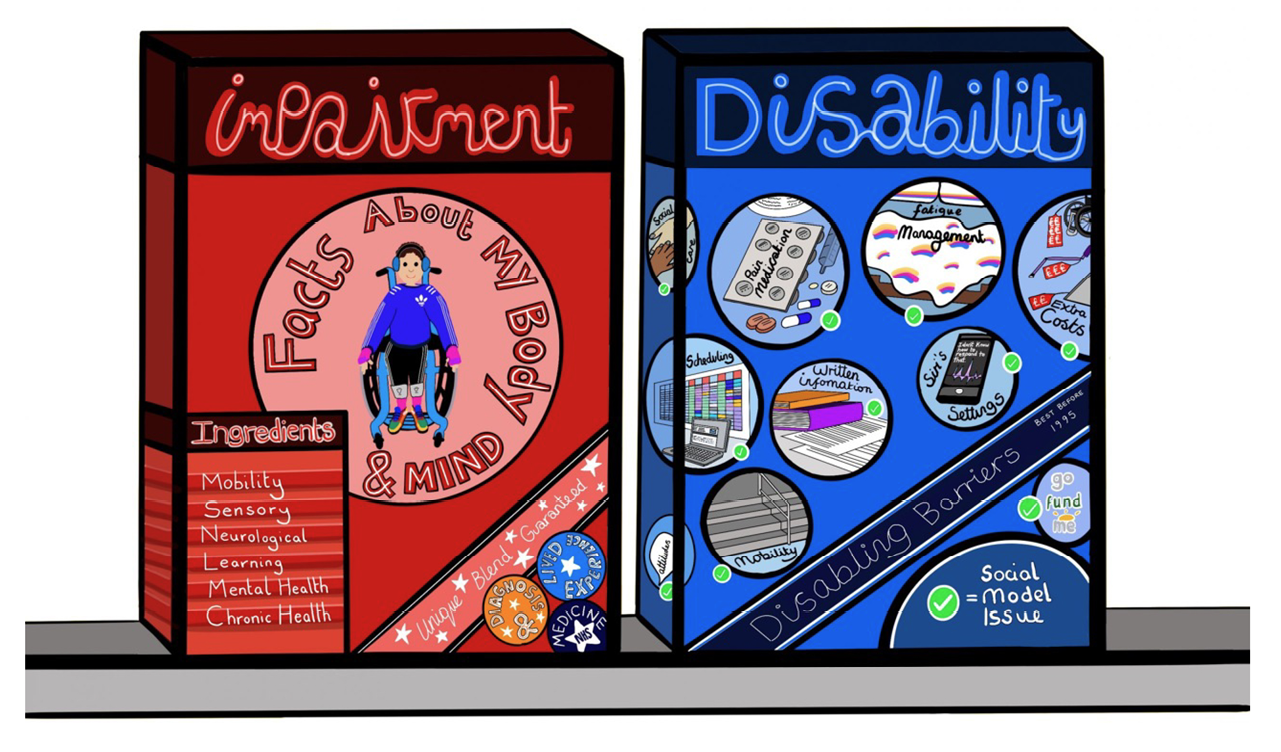

Touretteshero designed and delivered bespoke inclusive practice training for DHOTI. The intention was to introduce the young people from NYT who would be leading the project to disabled-led thinking and practice. The training included discussion of the different models of disability including those deemed problematic, such as the medical and charity models, and those which the project would build on, such as the social and strong social models (see Davis 1995; Oliver 1990, 2013; Crow 1996). The social model understands that people are not disabled by their impairments but by a societal failure to consider difference in how environments, systems and services are designed. The strong social model extends the social model and considers a ‘more complete understanding of disability and impairment as social concepts; and a recognition of an individual’s experiences of their body over time and in variable circumstances’ (Crow 1996: 218). The DHOTI training included discussion of accessible and inclusive language, aiming to create a shared and consistent understanding of which words would and would not be used within the project, and the rationale for this. The training also considered differences in key terms, such as the distinction between the word impairment (the facts about someone’s mind and body) and disability (the lived experience of disabling barriers). During the training sessions, each of these ideas was shared in creative ways, for example, the difference between the words impairment and disability was presented through illustrations of two colourful cereal boxes, created by Jess Thom (Figure 10.2).

Figure 10.2 Cereal boxes showing the distinction between ‘impairment’ and ‘disability’ (2020)

Image © Jessica Thom, 2023, all rights reserved

Discussions of language during the DHOTI training were framed by the affirmation model of disability, described as a ‘non-tragic view of disability and impairment which encompasses positive social identities, both individual and collective, for disabled people grounded in the benefits of life style and life experience of being impaired and disabled’ (Swain and French 2000: 569). The DHOTI training introduced central definitions of play as freely chosen, personally directed and intrinsically motivated (John and Wheyway 2004) as well as the United Nations ‘right to play’ (discussed later in this chapter). Following Walker’s (2004) collaborative model of disability equality training, an in-depth evaluation was undertaken with the young people involved after each phase of DHOTI. During the evaluation, the young people commented:

The training changed my perspective on disability and has enhanced how I want to make work in the future.

I got so much from the training that I took with me into the DHOTI project. I was feeling really nervous beforehand but the training calmed me down a lot and I felt empowered to work in a more inclusive way.

DHOTI—Phase Two

During the second phase of DHOTI, the pilot project was expanded to work with 124 disabled and/or neurodivergent young people aged between eleven and nineteen from two separate SEND schools in London. During the second phases of DHOTI the UK was not in a full lockdown but schools were restricted to working in small classroom bubbles. This meant that the majority of disabled young people were back in the school buildings but were restricted to working within one classroom and one consistent group of teachers, teaching assistants and students. The young people could not connect with students from other classroom bubbles. In conversations with teachers and families of the students during phase two of DHOTI, it became apparent that the students were missing opportunities to connect with people outside of their individual classroom bubbles. Therefore, creative ways for students to connect with each other became a key focus for the second phase of the project. Twenty young people aged fourteen to twenty-five were recruited by NYT to become makers and creative buddies for the second phase of the project. All of these young people received inclusive practice training from Touretteshero. Two additional training sessions were incorporated into the second phase of the project, working with teachers and teaching assistants from the two schools. Feedback from the creative buddies during the evaluation of the second phase of the project highlighted how the training with teachers made a significant improvement in how much the teachers engaged and supported the workshops. One young person commented:

The teachers were brilliant; they used Makaton and helped all the students take part—they were so much more involved than when we did the pilot.

The makers created 160 new top secret superhero kits which included additional tactile and sensory materials. The creative buddies used video conferencing software to join the young people in their school classrooms to work through the inclusive creative process over two three-hour workshops. These hybrid digital-physical play environments enabled meaningful creative relationships to be formed between disabled young people in London and creative buddies from across the UK.

The workshops during the second phase of DHOTI highlighted the significance of non-physical participation and interaction as a central component of inclusive play during the pandemic. The opportunities for human connection that were created during DHOTI serve, as Liddiard and others note, as a counter to normative ideas and expectations of face-to-face work as a point of superiority, affirming ‘technologies as spaces ripe for human and affective connection, nurture and care, especially for marginalised people who experience barriers in the physical and social world’ (2022: 7). During the workshops, the students used the materials in their superhero kits to transform their classrooms into new imaginative worlds—walls became planets, stars and solar systems. Chairs became caves and underground lakes. Doors became book covers to be opened and explored. The workshops culminated in a performance where the students showcased their new identities and shared their messages for the world within their classrooms. These performances were transmitted live between the different classrooms in the school using webcams and microphones, creating a multi-room creative exchange where each student could perform, watch and engage with their peers from across the school. The messages shared by the students ranged from humorous calls to action such as ‘I am Frying Pan Man and I will make school dinners better for all’ to poignant messages such as ‘To all my fellow superheroes in our school, I miss our playtime and want to know if you are ok’. After the performance feedback was gathered from students in different classrooms at the school using easy-read surveys and an iPad with a text-to-speech application. The students were all positive about the experience, with the exception of two who commented that some of the messages were hard to hear during the performance. One student commented, ‘it was good to see my friends in the other classes’, whilst another said, ‘I will be a superhero every day now, even at home with dad’.

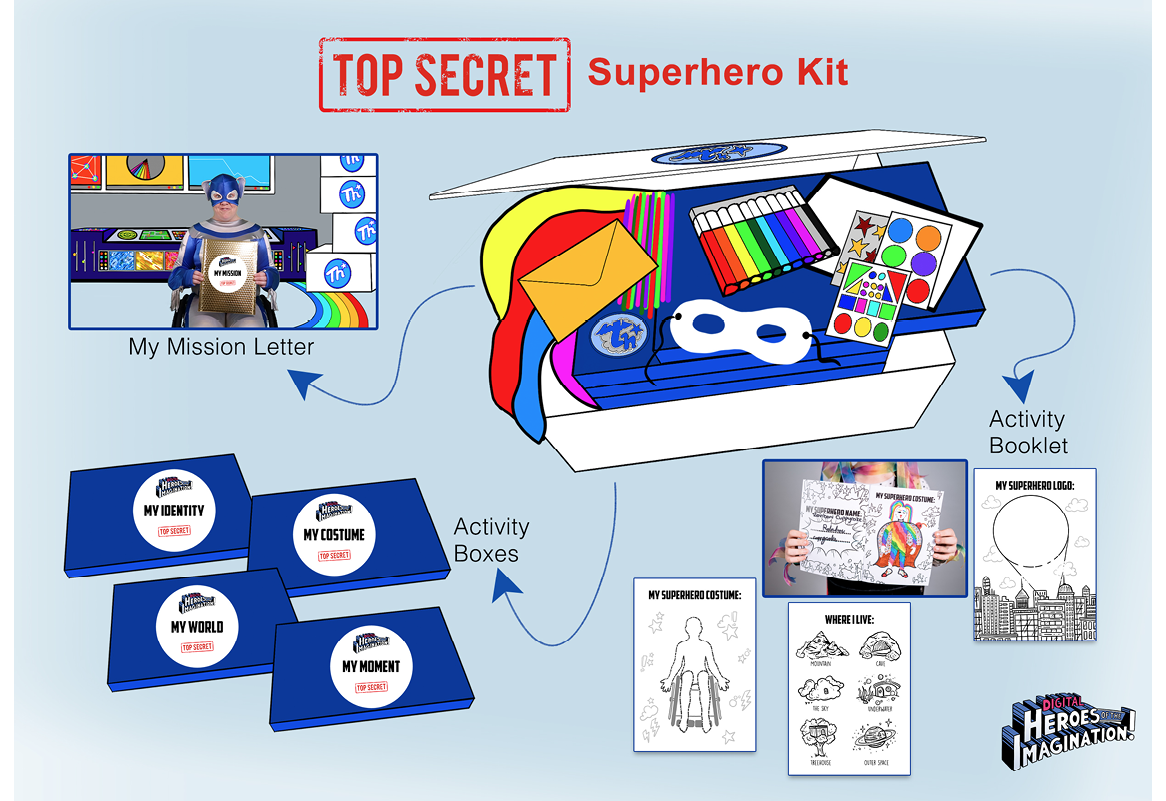

Top Secret Superhero Kits

A central component of DHOTI was the design of multi-sensory ‘Top Secret’ superhero kits. Informed by the Universal Design for Learning Framework (Rose and Meyer 2002), the materials and activities were designed to create meaningful opportunities to engage with the kit through different sensory channels, acknowledging that taking part will look and feel different for each student. Each kit included a welcome letter within a tactile visual envelope, four activity boxes—each with a distinct visual identity—easy-read instructions (Sutherland and Isherwood 2016) about how to take part, and a wealth of multi-sensory ‘loose part’ materials (Nicholson 1971). These materials included colourful wheelchair spoke covers, pens and sticky foam shapes (Figure 10.3). The superhero kits included materials that would be used for specific activities during the workshops but they were also designed to ensure that disabled young people had access to resources to use at home beyond the life of the project.

Figure 10.3 Top Secret Accessible Superhero Kit (2020)

Image © Touretteshero CIC, 2023, all rights reserved

Discussion

The following sections of this chapter reflect on the existing practices of inclusive play and consider how discourses of risk, resilience and the right to play are renewed by new forms of disabled-led play that emerged during the Covid-19 pandemic. Casey suggests that ‘the concept of inclusive play links inseparably the right to play and the right of disabled children to participate fully in society […] by aiming for inclusive play, we are simply aiming for the best play experiences we can offer to all children’ (2010: xi).

Risk and Resistance

Risk is a central component in discourses and practices of play. Cultures of risk in relation to play activity are continuously changing and many suggest that societal shifts in Western cultures towards risk aversion have engendered an understanding of ‘meaningful play’ as risk-free and highly controlled (Gill 2007). Ball et al. (2019: 4) contend that a ‘prominent driver of play opportunities—or lack thereof—has been the proliferate use of risk assessment’. Seale et al. (2013) argue that inclusive play and education are fundamentally an embodiment of positive risk-taking. Slee (2007) describes the primary connections between risk-taking and inclusive practices and Ainscow notes how positive risk-taking is ‘essential to the creation of more inclusive forms of pedagogy’ (1999: 71). Within inclusive play practice, risk-benefit assessments are often used to consider both risks and benefits towards informed judgements that consider a variety of issues relevant to localized circumstances (Ball, Gill and Spiegal 2008). Seale et al. (2013) extend this approach and present a conceptual framework of positive risk-taking in relation to disabled people’s experiences of learning and play. This framework argues that ‘practitioners need to balance the “what if something goes wrong” questions with “what if something goes right” questions’ (2013: 240). Covid-19 presented new questions with regards to risk and disabled children and young people’s play. Many SEND schools were necessarily focused on the immediate health risks that their disabled students were facing and prioritized minimizing the spread of the virus. Although this was undoubtedly a significant risk, Touretteshero was also concerned about the risks that were perhaps less obvious or given less priority in changes to SEND policy and practice. These included the social and political risks of disabled young people being isolated and disconnected from others that may be compounded by different communication preferences and the existing digital divide. Or the barriers to creative experiences for disabled children and young people through a lack of access to resources and materials.

A series of probing questions was created to frame the conversations around risk during the DHOTI project. These included:

- What are the risks to disabled young people if they can’t be creative or access creative, multisensory resources?

- What are the risks to disabled young people if they can’t stay creatively connected to their peers?

- What are the opportunities whilst working remotely for disabled young people to connect with other young people?

The pandemic accentuated an existing issue within discourses of risk, namely the tension between macro and micro risk practices. As Seale et al. note,

organisations respond to what might be perceived as ‘big risks’ such as abuse, personal safety or educational failure at a macro level by drawing up pre-planned policies, rules and guidelines. Individuals that work with and alongside these organisations are required to negotiate their response to these risks at a micro level. (2013: 238)

During the pandemic, with schools closed and governments across the globe creating frameworks in which populations could navigate the macro level risk of the Covid-19 virus, disabled children and young people, their parents, carers, siblings and close friends were negotiating the real-world micro risks of their everyday lives. In this context, dynamic new approaches to risk, risk-assessment and risk-benefit were created. Further questions were considered during DHOTI, such as

- Is the risk of delivering a box of accessible materials directly to a disabled young person’s house worth the benefit of that young person having access to the materials?

- Is the risk of using video conferencing software to work one-to-one with a disabled young person directly in their home environment (which pre-pandemic safeguarding policy would advise against) worth the benefit of the young person accessing creative activities and connections?

Within these negotiations of risk assessment and benefit new play cultures emerged, bringing together young NYT members from across the UK to build accessible resources and lead creative encounters with disabled young people in London in ways that, before the pandemic, would never have been conceived. In this context risk assessment and benefit informed new currencies of resilience in and between the young people involved. Resilience in this sense is understood as an act of resistance, following Goodley’s (2005) sociocultural framework where resilience is not an individual trait or characteristic but a political response to disabling and ableist circumstances. By placing inclusion and anti-ableist thinking at the centre of the DHOTI play encounters, the risks taken at the micro level informed new instances of what Mia Mingus describes as ‘access intimacy’:

That elusive, hard to describe feeling when someone else ‘gets’ your access needs […] Sometimes access intimacy doesn’t even mean that everything is 100% accessible. Sometimes it looks like both of you trying to create access as hard as you can with no avail in an ableist world. Sometimes it is someone just sitting and holding your hand while you both stare back at an inaccessible world. (2011)

Positive Memories as Protection

DHOTI emphasized the significant role that exciting, inclusive experiences of play can have in creating lasting positive memories for disabled children and young people. Research shows that when disabled children and young people share memories of play and learning in school contexts they often focus on the barriers they experienced (Díez 2010) and moments of segregation and discrimination (Shar 2007; Connor and Ferri 2007). Reviews of public playgrounds highlight that lack of accessible play equipment and the impact on meaningful equal play opportunities for disabled children and young people (Fernelius and Christensen. 2017; Ripat and Becker 2012). This highlights how the design of a play space sends a clear message about which bodies and minds have been considered. As Hamraie (2013) suggests, designed environments are not simply static structures in which humans exist and interact, but instead environments produce lived and embodied experiences and, at times, create physical and social barriers that can reinforce structural inequalities. Through engaging with non-accessible play spaces from an early age, disabled children learn to expect less. Even when accessible equipment is present, it is often a single item within an otherwise non-accessible playground. When disabled children and young people report positive memories of play, it is often within an environment that is not only physically accessible, but also where attitudes towards disabled people are positive (Jeanes and Magee 2012). As Wenger et al. argue, ‘to achieve inclusion on inclusive playgrounds, the physical, attitudinal, social, and political environments must be regarded as interrelated’ (2021: 144). At Touretteshero we often talk about the idea of positive memories as protection. This notion acknowledges that disabled children and young people will encounter barriers in their lives but that having lasting positive memories of events, environments or experiences where their requirements are met can serve as protection when things are challenging. It was clear during DHOTI that Touretteshero and NYT were not in a position to remove all of the physical and attitudinal barriers that disabled children and young people were experiencing due to the Covid-19 pandemic. It was also apparent that the pandemic would create lasting negative memories for many, if not all, disabled children and young people. Therefore the need to create moments of meaningful creative connection and positive experiences for disabled children and young people was more significant than ever.

Renewing The Right to Play

The contemporary understanding of the right to play was formalized in Article 31 of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC) which requires state parties to ‘recognize the right of the child to rest and leisure, to engage in play and recreational activities appropriate to the age of the child and to participate freely in cultural life and the arts’ (United Nations 1989). However, there are a number of publications that informed Article 31 of the UNCRC. The human right to rest and leisure (but not play) was established in Article 24 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in 1948 (United Nations 1948). Following this, the right to play was included in the Declaration of the Rights of the Child in 1959 which notes that children ‘shall have full opportunity for play and recreation, which should be directed to the same purposes as education; society and the public authorities shall endeavour to promote the enjoyment of this right’ (United Nations 1959). The International Play Association’s Declaration of the Child’s Right to Play (1979) calls for the child’s right to play as a fundamental priority for health. Despite the UNCRC being described as ‘the most complete statement of children’s rights ever produced [. . .] [and] the most widely-ratified international human rights treaty in history’ (UNICEF n.d.), the right to play and Article 31 has also been described as forgotten, ignored, misunderstood and, therefore, the least recognized right of children and young people (Fronczek 2009; Davey and Lundy 2011).

In 2013, the United Nations published General Comment No. 17 (2013) on the Right of the Child to Rest, Leisure, Play, Recreational Activities, Cultural Life, and the Arts (art. 31) to reassert the significance of Article 31 as fundamental to the health, well-being and quality of a child or young person’s life. Significantly, General Comment No. 17 raised specific concerns with regards to equal access and opportunities to play for disabled children. General Comment No. 17 also lists thirteen aspects of an optimum play environment through which Article 31 can be realized. These include accessible space, time, permission, materials, freedom from social exclusion and prejudice, and the recognition from adults of the value and legitimacy of a child’s rights (United Nations 2013). However, it is noted that whilst Article 31 and General Comment No. 17 are widely acknowledged, they are often overlooked or under-utilized in practice (Janot and Rico 2020; Sabatello, Landes, and McDonald 2022; Tonkin and Whitaker 2021). The United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities aims to assert disabled children and young people’s right to play by ensuring ‘that children with disabilities have equal access with other children to participation in play, recreation and leisure and sporting activities’ (United Nations 2006). It is noted that much of the research regarding disabled children and young people’s right to play has subsequently focused on inclusive environments and accessible play spaces (Goodley and Runswick‐Cole 2010), meaning that disabled children continue to experience discrimination within these play spaces and cultures (John and Wheyway 2004).

Research suggests that in times of crisis the fundamental right to play for all children is threatened through increased barriers to play, reduced access to space and a lack of permission (Wright and Reardon 2021; Gill and Miller 2020; Heldal 2021; Chatterjee 2017). Casey and McKendrick contend that

the Covid-19 pandemic afforded an opportunity to reappraise the status of play as a fundamental right of the child through the lens of play in crisis. However, children’s right to play was curtailed as it became collateral damage when managing the threat to public health [. . .] the staged lifting of restrictions highlighted the standing of play relative to other human rights, with the desire to facilitate return to work, children’s education and adult leisure being prioritised over facilitating opportunities for children’s play. (2022: 13-14)

DHOTI created an opportunity to reassert the role of play as a fundamental human right and to re-energise the principles of the right to play in a practical context. Documents such as UNCRC Article 31 and General Comment No. 17 should not be considered neutral in relation to the lived and embodied realities of a crisis such as the Covid-19 pandemic. In times of crisis these documents become more important than ever as ‘artifacts of knowing-making’ (Hamraie 2017), helping to bridge the gap between macro considerations about population health and well-being and the everyday priorities and realities of individuals negotiating crisis.

Conclusion

This chapter has reflected on DHOTI, a radical play project led by Touretteshero and NYT during the Covid-19 pandemic in England. The chapter has considered how discourses of risk, resilience and the right to play are renewed by new forms of disabled-led play such as DHOTI. The pandemic has emphasized how disabled children and young people, their rights, and their experiences of play are so often secondary to the perspectives of their non-disabled peers. This affirms what Goodley describes as a dislocation of disabled young people from our play and educational communities where ‘disabled students appear at the end of the educational conversation, as a postscript, the addendum or the complicating outliers’ (2021: 122). Although Covid-19 undoubtedly created a significant threat to the fundamental right to play, DHOTI, alongside other play projects across the globe (see Casey and McKendrick 2022), highlight how a child’s right to play can be actively protected, promoted, or improved during times of crisis. DHOTI suggests that we should keep taking risks and understand that risky play for disabled children and young people can lead to moments of ‘access intimacy’ and new understandings of resilience—not as an individual trait but as an act of anti-ableist resistance. DHOTI also highlights how positive memories can protect disabled children and young people when things become challenging. As researchers and practitioners with an interest in play, we should seek to build more inclusive cultures (in whatever context, crisis or no crisis) in which disabled people can thrive. If, as Casey and McKendrick suggest, the Covid-19 pandemic has shown ‘the seeds of opportunity to sustain and strengthen our support for children’s right to play’ (2022: 14), then the perspectives of disabled children and young people must be brought to the centre. Disabled people hold a unique legacy of resilience and resistance to societal inequalities that predates the Covid-19 pandemic. Existing calls for the emancipation of disabled children’s play (Goodley and Runswick‐Cole 2010) and the Principles of Disability Justice (Berne et al. 2018) provide important building blocks in steering a critical, rights-based trajectory for play theory and practice beyond the pandemic. By thinking from an intersectional perspective, promoting leadership of the most impacted and aiming for collective access against normative expectations, new processes of play as collective liberation can emerge. And thanks to DHOTI, there are 148 new disabled superheroes who are ready to lead us into this future.

Works Cited

Abrams, Thomas, and David Abbott. 2020. ‘Disability, Deadly Discourse, and Collectivity amid Coronavirus (COVID-19)’, Scandinavian Journal of Disability Research, 22: 168–74, https://doi.org/10.16993/sjdr.732

American Psychiatric Association. 2013. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edn (Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association)

Ainscow, Mel. 1999. Understanding the Development of Inclusive Schools (London: Falmer)

Ball, David, Tim Gill, and Bernard Spiegal. 2008. Managing Risk in Play Provision: Implementation Guide (Play England), https://dera.ioe.ac.uk/8625/1/00942-2008DOM-EN.pdf

Ball, David, et al. 2019. ‘Avoiding a Dystopian Future for Children’s Play’, International Journal of Play, 8: 3-10, https://doi.org/10.1080/21594937.2019.1582844

Berne, Patricia, et al. 2018. ‘Ten Principles of Disability Justice’, WSQ: Women’s Studies Quarterly, 46: 227-30, https://doi.org/10.1353/wsq.2018.0003

Bosworth, Matthew L., et al. 2021. ‘Deaths Involving Covid-19 by Self-reported Disability Status during the First Two Waves of the Covid-19 Pandemic in England: A Retrospective, Population-based Cohort Study’, Lancet Public Health, 6: e817–25, https://doi.org/10.1016/S2468-2667(21)00206-1

Brennan, Clara Siobhan. 2020. Disability Rights during the Pandemic: A Global Report on Findings of the COVID-19 Disability Rights Monitor, https://www.internationaldisabilityalliance.org/sites/default/files/disability_rights_during_the_pandemic_report_web_pdf_1.pdf

Brodin, Jane. 2005. ‘Diversity of Aspects on Play in Children with Profound Multiple Disabilities’, Early Child Development and Care, 175: 635–46, https://doi.org/10.1080/0300443042000266222

Bruce, David, and others. 2013. ‘Multimodal Composing in Special Education: A Review of the Literature’, Journal of Special Education Technology, 28: 25–42, https://doi.org/10.1177/0162643413028002

Burke, Jenene, and Amy Claughton. 2019. ‘Playing with or Next to? The Nuanced and Complex Play of Children with Impairments’, International Journal of Inclusive Education, 23: 1065-080, https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2019.1626498

Cacioppo, Marine, et al. 2021. Emerging Health Challenges for Children with Physical Disabilities and Their Parents during the Covid-19 Pandemic: The ECHO French Survey’, Annals of Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine, 64: 101429, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rehab.2020.08.001

Casey, Theresa. 2010. Inclusive Play: Practical Strategies for Children from Birth to Eight (London: SAGE)

Chambers, Dianne, Zeynep Varoglu, and Irmgarda Kasinskaite-Buddeberg. 2016. Learning for All: Guidelines on the Inclusion of Learners with Disabilities in Open and Distance Learning, UNESCO Programme: From Exclusion to Empowerment, https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000244355

Chatterjee, Sudeshna. 2017. Access to Play for Children in Situations of Crisis: Synthesis of Research in Six Countries (International Play Association), http://ipaworld.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/IPA-APC-Research-Synthesis-Report-A4.pdf

Conn, Carmel, and Sharon Drew. 2017. ‘Sibling Narratives of Autistic Play Culture’, Disability & Society, 32: 853-67, https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2017.1321526

Connor, D.J., and B.A. Ferri. 2007. ‘The conflict within: Resistance to inclusion and other paradoxes in special education’, Disability & Society, 22 (1): 63–77

Connors, Clare, and Kirsten Stalker. 2007. ‘Childhood Experiences of Disability: Pointers to a Social Model of Childhood Disability’, Disability & Society, 22 (1): 19–33, https://doi.org/10.1080/09687590601056162

Davey, Ciara, and Laura Lundy. 2011. ‘Towards Greater Recognition of the Right to Play: An Analysis of Article 31 of the UNCRC’, Children & Society, 25: 3–14, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1099-0860.2009.00256.x

Davis, Lennard J. 1996. Enforcing Normalcy: Disability, Deafness, and the Body (London: Verso)

Díez, Anabel Moriña. 2010. ‘School Memories of Young People with Disabilities: An Analysis of Barriers and Aids to Inclusion’, Disability & Society, 25: 163-75, https://doi.org/10.1080/09687590903534346

Fernelius, Courtney L., and Keith M. Christensen. 2017. ‘Systematic Review of Evidence-Based Practices for Inclusive Playground Design’, Children, Youth and Environments, 27: 78–102, https://doi.org/10.7721/chilyoutenvi.27.3.0078

Fronczek, Valerie. 2009. ‘Article 31: A Forgotten Article of the UNCRC’, Early Childhood Matters, 113: 24–28

Gill, Tim, and Robyn Monro Miller. 2020. Play in Lockdown: An International Study of Government and Civil Society Responses to Covid-19 and Their Impact on Children’s Play and Mobility (International Play Association), https://ipaworld.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/IPA-Covid-report-Final.pdf

Goodley, Dan. 2005. ‘Empowerment, Self-advocacy and Resilience’, Journal of Intellectual Disabilities, 9: 333-43, https://doi.org/10.1177/1744629505059

——. 2021. Disability and other Human Questions (Bingley: Emerald)

GOV.UK. n.d. ‘Children with Special Educational Needs and Disabilities (SEND)’, https://www.gov.uk/children-with-special-educational-needs/extra-SEN-help

Graber, Kelsey M., et al. 2021. ‘A Rapid Review of the Impact of Quarantine and Restricted Environments on Children’s Play and the Role of Play in Children’s Health’, Child: Care, Health and Development, 47: 143–53, https://doi.org/10.1111/cch.12832

Hamraie, Aimi. 2017. Building Access: Universal Design and the Politics of Disability (Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press)

Hamraie, Aimi. 2013. ‘Designing Collective Access: A Feminist Disability Theory of Universal Design’, Disability Studies Quarterly, 33, https://dsq-sds.org/article/view/3871/3411

Hashey Andrew I., and Skip Stahl. 2014. ‘Making Online Learning Accessible for Students With Disabilities’, TEACHING Exceptional Children, 46: 70-78, https://doi.org/10.1177/0040059914528329

Heldal, Marit. 2021. ‘Perspectives on Children’s Play in a Refugee Camp’, Interchange, 52: 433–45, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10780-021-09442-4

International Play Association (IPA). 1979. ‘IPA Declaration of the Child’s Right to Play’, http://ipaworld.org/about-us/declaration/ipa-declaration-of-the-childs-right-to-play/

Jahr, Eric, Sigmund Eldevik, and Svein Eikeseth. 2000. ‘Teaching Children with Autism to Initiate and Sustain Cooperative Play’, Research in Developmental Disabilities, 21: 151–69, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0891-4222(00)00031-7

Janot, Jaume Bantulà, and Andrés Payà Rico. 2020. ‘The Right of the Child to Play in the National Reports Submitted to the Committee on the Rights of the Child’, International Journal of Play, 9: 400–13, https://doi.org/10.1080/21594937.2020.1843803

Jeanes, Ruth, and Jonathan Magee. 2012. ‘“Can we play on the swings and roundabouts?”: Creating Inclusive Play Spaces for Disabled Young People and Their Families’, Leisure Studies, 31: 193-210, https://doi.org/10.1080/02614367.2011.589864

de Lannoy, Louise. 2020. ‘Regional Differences in Access to the Outdoors and Outdoor Play of Canadian children and Youth during the Covid-19 Outbreak’, Canadian Journal of Public Health, 111: 988–94, https://doi.org/10.17269/s41997-020-00412-4

Liddiard, Kirsty, et al. 2022. Living Life to the Fullest: Disability, Youth and Voice (Bingley: Emerald)

Lloyd, Christine. 2008. ‘Removing Barriers to Achievement: A Strategy for Inclusion or Exclusion?’ International Journal of Inclusive Education, 12: 221–36, https://doi.org/10.1080/13603110600871413

Manganello, Jennifer A. 2021. ‘Media Use for Children with Disabilities in the United States during Covid-19’, Journal of Children and Media, 15: 29–32, https://doi.org/10.1080/17482798.2020.1857281

Masi Anne, et al. 2021. ‘Impact of the Covid-19 Pandemic on the Well-being of Children with Neurodevelopmental Disabilities and Their Parents’, Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health, 57: 631-36, https://doi.org/10.1111/jpc.15285

Messier, Julie, Francine Ferland, and Annette Majnemer. 2008. ‘Play Behavior of School Age Children with Intellectual Disability: Their Capacities, Interests and Attitudes’, Journal of Developmental Physical Disability, 20: 193–207, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10882-007-9089-x

Mingus, Mia. 2011. ‘Access Intimacy: The Missing Link’, https://leavingevidence.wordpress.com/2011/05/05/access-intimacy-the-missing-link/

Mitchell, Jennifer, and Bonnie Lashewicz. 2018. ‘Quirky Kids: Fathers’ Stories of Embracing Diversity and Dismantling Expectations for Normative Play with their Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder’, Disability & Society, 33: 1120-137, https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2018.1474087

Moore, Sarah A., et al. 2021. ‘Adverse Effects of the Covid-19 Pandemic on Movement and Play Behaviours of Children and Youth Living with Disabilities: Findings from the National Physical Activity Measurement (NPAM) Study’, International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18: 12950, https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182412950

Nicholson, Simon. 1971. ‘How Not to Cheat Children: The Theory of Loose Parts’, Landscape Architecture, 62: 30–34

Office for National Statistics. 2022. Updated Estimates of Coronavirus (COVID-19) Related Deaths by Disability Status, England: 24 January 2020 to 9 March 2022, file:///C:/Users/Editor/Downloads/Updated%20estimates%20of%20coronavirus%20(COVID-19)%20related%20deaths%20by%20disability%20status,%20England%2024%20January%202020%20to%209%20March%202022.pdf

Oliver, Michael. 1990. The Politics of Disablement (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan)

Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development. 2001. Understanding the Digital Divide, OECD Digital Economy Papers, 49 (Paris: OECD), https://doi.org/10.1787/236405667766

Porter, Maggie L., Maria Hernandez-Reif, and Peggy Jessee. 2008. ‘Play Therapy: A Review’, Early Child Development and Care, 179: 1025–040, https://doi.org/10.1080/03004430701731613

Prout, Alan, and Allison James. 1997. ‘A New Paradigm for the Sociology of Childhood’, in Constructing and Reconstructing Childhood, ed. by Allison James, 2nd edn (London: Falmer Press), pp. 7–33

Public Health England. 2020. Deaths of People Identified as Having Learning Disabilities with Covid-19 in England in the Spring of 2020, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/933612/COVID-19__learning_disabilities_mortality_report.pdf

Public Health Scotland. 2021. The Impact of Covid-19 on Children and Young People in Scotland: 10–17 Year-Olds (Edinburgh: Public Health Scotland), https://www.publichealthscotland.scot/media/2999/the-impact-of-covid-19-on-children-and-young-people-in-scotland-10-to-17-year-olds_full-report.pdf

Reeve, Donna. 2012. ‘Psycho-emotional Disablism: The Missing Link?’ in The Routledge Handbook of Disability Studies, ed. by Nick Watson, Alan Roulstone and Carol Thomas (London: Routledge), pp. 78-92

Ripat, Jacquie, and Pam Becker. 2012. ‘Playground Usability: What Do Playground Users Say?’ Occupational Therapy International, 19: 144-53, https://doi.org/10.1002/oti.1331

Rose, David H., and Anne Meyer. 2002. Teaching Every Student in the Digital Age: Universal Design for Learning (Alexandria, VA: ASCD)

Sabatello, Maya, Scott D. Landes, and Katherine E. McDonald. 2020. ‘People with Disabilities and Covid-19: Fixing Our Priorities’, American Journal of Bioethics, 20: 187-90, https://doi.org/10.1080/15265161.2020.1779396

Shah, Sonali. 2007. ‘Special or Mainstream? The Views of Disabled Students’, Research Papers in Education, 22: 425–42, https://doi.org/10.1080/02671520701651128

Slee, Roger. 2007. ‘Inclusive Schooling as a Means and End of Education?’ in The SAGE Handbook of Special Education, ed. by Lani Florian, (London: SAGE), pp. 161-70, https://dx.doi.org/10.4135/9781848607989.n13

Stillianesis, Samantha, et al. 2021. ‘Parents’ Perspectives on Managing Risk in Play for Children with Developmental Disabilities’, Disability & Society, 37: 1272-292, https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2021.1874298

Sutherland, Rebecca Joy, and Tom Isherwood. 2016. ‘The Evidence for Easy-Read for People With Intellectual Disabilities: A Systematic Literature Review’, Journal of Policy and Practice in Intellectual Disabilities, 13: 297-310, https://doi.org/10.1111/jppi.12201

Swain, John, and Sally French. 2000. ‘Towards an Affirmation Model of Disability’, Disability & Society, 15: 569-82, https://doi.org/10.1080/09687590050058189

Thomas, Carol. 2007. Sociologies of Disability, ‘Impairment’, and Chronic Illness: Ideas in Disability Studies and Medical Sociology (London: Macmillan Education)

Tonkin, Alison, and Julia Whitaker. 2021. ‘Play and Playfulness for Health and Wellbeing: A Panacea for Mitigating the Impact of Coronavirus (Covid 19)’, Social Sciences & Humanities Open, 4: 100142, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssaho.2021.100142

UNESCO. 2020a. Covid-19. A Global Crisis for Teaching and Learning, https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000373233/PDF/373233eng.pdf.multi

——. 2020b. Inclusive School Reopening: Supporting the Most Marginalized Children to go to School, https://en.unesco.org/sites/default/files/inclusive_school_reopening_-_supporting_marginalised_children_during_school_re._.pdf

——. 2021. Understanding the Impact of Covid-19 on the Education of Persons with Disabilities: Challenges and Opportunities of Distance Education: Policy Brief, https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000378404.locale=en

UNICEF. 2020. Children with Disabilities: Ensuring their Inclusion in Covid-19 Response Strategies and Evidence Generation, https://data.unicef.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/Children-with-disabilities-COVID19-response-report-English_2020.pdf

——. n.d. ‘How We Protect Children’s Rights with the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child’, https://www.unicef.org.uk/what-we-do/un-convention-child-rights/

United Nations 1948. Universal Declaration of Human Rights, https://www.un.org/en/about-us/universal-declaration-of-human-rights

——. 1959. Declaration of the Rights of the Child, https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/195831?ln=en

——. 1989. Convention on the Rights of the Child, https://www.unicef.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/unicef-convention-rights-child-uncrc.pdf

——. 2006. The United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, https://www.un.org/disabilities/documents/convention/convention_accessible_pdf.pdf

——. 2013. General Comment No. 17 on the Right of the Child to Rest, Leisure, Play, Recreational Activities, Cultural Life, and the Arts (art. 31) (Committee on the Rights of the Child), https://www.refworld.org/docid/51ef9bcc4.html

Wenger, Ines, et al. 2021. ‘Children’s Perceptions of Playing on Inclusive Playgrounds: A Qualitative Study’, Scandinavian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 28: 136-46, https://doi.org/10.1080/11038128.2020.1810768

Wright, Hannah, and Mitchell Reardon. 2021. ‘Covid-19: A Chance to Reallocate Street Space to the Benefit of Children’s Health?’ Cities & Health, 11 May, https://doi.org/10.1080/23748834.2021.1912571

Zarzycka, Ewelina, et al. 2021. ‘Distance Learning during the Covid-19 Pandemic: Students’ Communication and Collaboration and the Role of Social Media’, Cogent Arts & Humanities, 8: 1953228, https://doi.org/10.1080/23311983.2021.1953228

1 An EHC plan is ‘for children and young people aged up to 25 who need more support than is available through special educational needs support. EHC plans identify educational, health and social needs and set out the additional support to meet those needs’ (GOV.UK n.d.).

2 Makaton is a unique visual language often used by people with learning disabilities and autistic people combining ‘symbols, signs and speech to enable people to communicate’ (see https://makaton.org).