11. Play and Vulnerability in Scotland during the Covid-19 Pandemic

© 2023, Nicolas Le Bigre, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0326.11

Introduction

When the UK Government announced on 23 March 2020 that the population would be under effective ‘lockdown’ due to risks from the coronavirus, the general feeling in Scotland seemed grim but resilient. There was uncertainty for the future but clarity on how we should act in the face of this danger. Soon stoicism gave way to hope. Rainbow images started to fill windows; playful messages to neighbours and loved ones appeared in public places; those privileged enough to have stable internet access embraced online interactions of various kinds; eventually new and familiar street games were carefully and creatively marked down in chalk; original forms of public-facing community interventions appeared—all of these enticing us to find togetherness, joy, strength and hope for the future. But just as quickly as we learned the promising possibilities of play within the (ever-changing) rules of our new lockdown lives, the pressures of resilience and the growing stakes of a world of growing inequities and real mortal danger led to disappointment, and eventually to new, more cynical forms of play, perhaps better attuned to the realities of a multi-year pandemic that has led to almost fifteen thousand deaths in Scotland, 178,000 in the UK as a whole, and almost fifteen million direct and indirect excess deaths worldwide (National Records of Scotland 2022; World Health Organization 2022). But though forms of play during the pandemic have shifted, they have not disappeared, in line with the belief of folklorist W. F. H. Nicolaisen that ‘what keeps people going most of the time is not the heavy tear of weeping but our eyes awash with tears of laughter’ (1992: 39).

In this chapter I use examples from contributions to the Lockdown Lore Collection Project at the University of Aberdeen to examine pandemic play through the lens of vulnerability, within the contexts of my disciplines of ethnology and folklore. Though play can protect players by necessitating singular focus, play in any context also exposes the vulnerability of the players (Goldstein 2004: 5; Lindgren 2017: 162). This vulnerability can hint at the reasons why we play, how we play, why we need to play, and how changes in play and wider societal contexts go hand in hand. The selected examples of play highlight several themes that can be gathered under a broader category of vulnerability, including a fear of the ephemerality of community, apprehension at physical vulnerability to the virus, distress caused by societal pressures to come together, intergenerational differences and difficulties, lack of technological adeptness, loss of physical contact, fear of an unknowable future, and externally imposed limitations. It examines pandemic play in the widest sense within overlapping Scottish contexts, considering play amongst communities, children, families and adults, and even in the contexts of ethnography and ethnographers.

Though Scotland is at the heart of the text, it is impossible to ignore the wider UK context and the fact that this pandemic has been a global one. Despite having experienced great solitude, many people have also been more digitally, and thus globally, connected than ever before. Interpretation of play in Scotland cannot and should not therefore be limited to Scotland and doubtless at any given wakeful moment there are people in Scotland who are playing with friends, family and strangers from around the world. In looking at a wide range of examples from across these groups and contexts, this chapter considers how play has changed according to the vicissitudes of the pandemic and the political and societal contexts enfolded in it. It considers physical play and virtual play, and the various physical and virtual hybridities that exist amongst them, all while keeping the concept of vulnerability at the forefront.

Methodology, Ethics and Reflexivity

The Lockdown Lore Collection Project,1 which is the source for all of the data herein, was launched in April 2020, and is part of the Elphinstone Institute Archives at the University of Aberdeen (Le Bigre 2020). It came about when, living in Leith in the north of Edinburgh at the onset of the pandemic, I was suddenly isolated from my students and colleagues in Aberdeen where I had, until then, commuted weekly. Unable to travel, I was curious to know if other parts of Scotland were also starting to be dotted with rainbows and other creative responses to the pandemic. In online discussions with colleagues, I proposed an idea for a public call-out for photos from around the country, following the model of a smaller project I had coordinated documenting signs from the Scottish Independence Referendum in 2014. As a folklorist, I was naturally curious as to what other forms of creative responses might exist so I added more overarching categories for creative forms including writing, songs and tunes. My colleague Simon Gall sagely suggested we document online initiatives developed during the pandemic so we added that to the mix. Thankfully contributors ignored this narrow initial list of categories and submitted wide-ranging creative responses that I could never have predicted. Finally, I realized the potential for using online platforms to conduct semi-structured interviews and, as personal experience narratives are at the core of most of my research, I thought it important to speak to people about their lives during the pandemic while we were all living through it, following Carl Lindahl’s belief that ‘shared experience seem[s] to make the story easier to tell’ (2018: 231). The goal of the project was, and is, two-fold: to document for the long term Scotland’s creative responses to the coronavirus pandemic, all while gaining an understanding of people’s everyday routines, as well as thoughts, feelings, fears and hopes.

Helping me in this task (and, indeed, conducting most of the interviews) were twelve volunteer interviewers who were either past or current students and, in one case, a sociologist colleague. In total, the project has resulted in over three thousand submissions and seventy interviews, with further follow-up interviews scheduled for the near future. Because the online component—both through the contribution form and the interviews—is innate to the project, those without steady online access or a certain level of digital literacy will not have been able to participate easily. In this sense, although the project could not have existed offline during the lockdown context, it also means that the participants represent a narrower portion of society than I would have liked, the online context unintentionally excluding many of those dealing with pandemic vulnerabilities on multiple intersectional levels. We did not directly collect demographic data for contributions to the project as it was seen as an archival rather than a research project, and such questions can dissuade contributions more than encourage them. Interviewees have been self-selecting in that they contact me through an online form if they want to be interviewed, meaning they 1) have to be interested in the project and 2) have to have time to participate, both of which have presumably further narrowed the pool of contributors. But the contributions we have received have been deeply valuable. Participants have mostly been in their thirties to seventies and represent people who are single, married, without children, parents, in a variety of occupations and from various ethnic backgrounds (though principally white), representing several different levels of education.

All fieldwork was conducted diligently and ethically, with each interviewee completing a detailed consent form. Contributors submitting items to the project consented to their use covering all the possible outputs of the project, while also ensuring that any submitted photos, writings, songs and tunes were their own creation. I took a large number of photos as part of the project, and I always ensured that photos in public places—for example of window rainbows—were taken ethically, with only the item in question being the focus of the photo. All of the examples of public forms of play described below are from my own fieldwork.2 What is described in this chapter reflects only a miniscule proportion of the total collection (which has yet to be fully catalogued) but the items have been selected to illustrate points on play and vulnerability. Play was never an explicit focus of the project or the interviews but its presence is inescapable in the responses. Contributors’ names have only been used with their consent. In one instance I conducted online research into an anti-vaccination group. I have decided not to name this group. Reflexively, I must admit to being wary of boosting what I believe to be misinformation, and this group’s social media posts indicate that it is eager to be searchable and mentioned in writing. I have only generally referenced posts from the organization’s online channels that were publicly accessible and targeting a wide audience.

Finally, in a chapter about play, and while thinking reflexively, it would be remiss of me to neglect mentioning that, for ethnographers, play can sometimes be at the heart of our own fieldwork. Though perhaps one should not admit to it, there is a certain thrill at documenting new forms of creativity, of ‘collecting’ as many examples as possible, of finding synchronicity in the words of others. When listening back to some of the interviews conducted by the project interviewers—who in a few cases interviewed each other—I noticed subtle forms of play in their interviews, sometimes in light-hearted references to the project or their roles as interviewers, or to the long-term archival goals of the project. There were also hints of vulnerability in their own comments, for example, joking and worrying about my reactions to sound quality or other similar remarks. In this sense, it is important to realize that we fieldworkers are not separate from the people we interview; we are one and the same, and play has sustained us in our lives and work just as it has for others.

Vulnerability in Pandemic Play

When the UK Prime Minister, Boris Johnson, announced on 23 March 2020 that a lockdown would be imposed across England, Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales, he listed the limited purposes for which people would be allowed to leave their homes. In addition to unavoidable travel and shopping for basic necessities, Johnson mentioned that UK residents were allowed ‘one form of exercise a day—for example a run, walk, or cycle—alone or with members of your household’ (Prime Minister’s Office 2020). Though this clause was meant to limit the amount of time people spent outdoors, in many cases the government’s ‘daily exercise’ allowance encouraged people who might not usually exercise to do so (Harding 2020). With playgrounds closed (in Scotland these closures continued until June 2020), this combination of staying at home with concentrated moments of outdoor living, resulted in forms of public play that concentrated in a few specific areas: windows, driveways, streets and public paths and, of course, virtual contexts as well.

By the end of March 2020, rainbows had suddenly become a symbol of hope and community resistance against the virus in the UK. Though the origins of the rainbow are unclear—apparently inspired either by a public call out by a National Health Service (NHS) nurse or a mother in Newcastle (Kleinman 2020; Marlborough 2020)—soon rainbows appeared as part of window displays, on public walls and paths and, in one case I documented, colouring each step of the outer stairs of a house in Edinburgh’s Restalrig neighbourhood. The rainbows were often created by children and their families, a form of hopeful play during a difficult, vulnerable time, often with accompanying messages in support of key workers. Though most rainbows were simply individual expressions of creativity, reaching out to the wider community in theme if not by other direct means, in some cases rainbows playfully ‘spoke’ to their neighbours. These communal expressions of hope could be found across Edinburgh, though they often varied depending on neighbourhood, residence type, and the social demographics of each area, as can be seen in the following examples. On a middle-class, terraced street in Leith, one window rainbow in the shape of a heart was preceded by the text ‘We LOVE your rainbow Number 42’, addressing the neighbours across the street who had a brightly painted rainbow on paper in their own window. In a reference to hope, local pride and possibly rainbows, residents at the nearby ‘Banana Flats’, a well-known block of council flats that curves like a banana, regularly set up a large speaker system across residences to play the beloved Proclaimers song, ‘Sunshine on Leith’ (1988), at high volume. Residents in that building and other nearby buildings, all featuring window rainbows, would sing along, allowing for aural community building and play. Just west of Leith, in the well-to-do neighbourhood of Trinity, community play amongst neighbours was on full display, with the windows across four storeys of a traditional sandstone tenement featuring parts of four enormous rainbows, spanning the entire building. This concerted effort would have taken a great deal of coordination but its impressive, unmissable message of hope and communal resistance in the face of a deadly virus was clear.

These reflections of community feeling and purpose were confirmed in many of the interviews conducted as part of the Lockdown Lore Collection Project, as seen in this quotation from an Aberdeen-based librarian in her forties in an interview conducted by interviewer Natalie Brown:

And so I think it’s maybe brought out a sense of community that isn’t always apparent, especially when you live in a city. You know, it’s maybe a bit more different when you live in a smaller place but, in a city, you don’t really have that proper community feel. But I would definitely say that, roundabout where we are just now, everybody is pulling together and just watching out for each other, which is a positive and hopefully that will continue afterwards. (Anonymous 2020)

These words aptly describe the discovery and creation of community that many felt at the beginning of the pandemic. Such descriptions of newfound community also seemed to inspire—at least in my everyday contexts and observations—discussions of a post-pandemic ‘new normal’. Indeed, Policy Scotland and Scotland’s Third Sector Research Forum hosted an online seminar in which I participated called ‘Priorities for the “New Normal”: Lessons in Lockdown Research’ in August 2020. Communal play, quieter streets, and rising awareness of societal inequities showed a path to a future of communality, climate justice and social equity, though the subtext of this was an awareness of the inherent fragility and potential fleeting nature of this coming together, the unspoken fear that communal acts would not last and that they were just part of a game people played to distract themselves during a time of acute vulnerability.

Beyond this existential susceptibility, play in the community also indicated other forms of vulnerability. Not all forms of community play were coordinated amongst neighbours or large groups of people. In early April 2020, on the paths along the Water of Leith in Edinburgh, my wife and I came across a series of coloured signs tacked to adjacent trees with painted messages like ‘Don’t worry be happy’, with ‘happy’ represented by a golden sparkly smiley face (Figure 11.1).

Figure 11.1 ‘Colourful Sign on Water of Leith Path, Edinburgh’, 4 April 2020

Photo © Nicolas Le Bigre, 2023, all rights reserved

Underneath one of the signs was a note by a grandparent saying that their five-year-old granddaughter had wanted to ‘make everybody smile’. The notes also asked passers-by not to remove the images—vulnerable to a passer-by’s touch—but instead to take a photo to post on Facebook, demonstrating the hybrid physical/online nature of much of the play during the pandemic, in which corporations mediate the existence and presentation of play in online spaces (Gillis 2011: 167). On the other side of the path, in a small recess in a stone wall, the same grandparent-granddaughter team had placed two boxes. One held toys and the other held books and DVDs, with a message saying: ‘I have cleaned these with antibacterial wipes! Please take one and feel free to leave one of yours the next time you pass’. A small note in different coloured ink contained the response ‘Thank you! Made our toddler very happy! xxx’. Here the reference to disinfection reveals the vulnerable contexts in which play was being conducted. Even the original note implicitly reveals the stringent rules of the early lockdown, during which there was ambiguity as to how many members of a household were allowed to exercise together, thus one grandparent and their granddaughter creating the trail of images and gifts. The granddaughter’s reference to ‘worry’ also gives insight into the experiences, fears and hopes of young children during the period and their concern for the wellbeing of others.

Some forms of community play made the virus a central part of their message. On the door of their house in Leith, one family put up an image of a dog with a humorous note saying ‘BEWARE OF THE DOG (HE’S SELF ISOLATING)’ (Figure 11.2). There is no skirting around the virus in this creation but in its satirical play on traditional ‘beware of the dog’ signs, the sign simultaneously creates fun while highlighting the oft-unspoken dangers otherwise represented by rainbows and other signs of hope.

Figure 11.2 ‘Humorous Beware of Dog Sign, Leith, Edinburgh’, 25 March 2020

Photo © Nicolas Le Bigre, 2023, all rights reserved

Likewise, in early April 2020, at an allotment garden in the north of Edinburgh, I photographed a fashion-forward scarecrow featuring eye-catching green and black stockings and matching scarf, a conspicuous black-and-white dress, a hat and, most notably for this discussion, a pair of goggles and a mask (Figure 11.3). Had the mannequin-turned-scarecrow featured hands, it no doubt would have been wearing gloves. Sure to scare away peckish birds, the scarecrow was also certain to attract the attention of neighbours passing by, provoking a laugh while also perfectly manifesting the grave danger of the virus. That it was created at a time preceding any UK or Scottish government policy or advice on mask-wearing reflects the awareness of global responses to the pandemic at the time, with some other countries having already adopted mask mandates. In this sense, the scarecrow can be seen both as a form of humorous community-building play and an awareness-raising measure, highlighting different physical vulnerabilities and corresponding ways of staying safe during the pandemic. For any local residents aware that the nearby park, Leith Links, had been used as an isolation area and mass grave for plague victims in 1645, the message would have been even more poignant (Robertson 1862, cited in Oram 2007).

Figure 11.3 ‘Masked Scarecrow, Leith, Edinburgh’, 5 April 2020

Photo © Nicolas Le Bigre, 2023, all rights reserved

I discovered similar examples across the Edinburgh area, first with a droll example in the Water of Leith in which the standing nude statue of the artist Anthony Gormley had been modified after someone waded into the river and added a mask as its only item of clothing. Later I came across a public statue in Musselburgh, ‘The Musselburgh Archer’, which had been adorned with mask, gloves, scarf and hoodie, and holding in his hand not a bow but a bottle of hand sanitizer. This form of play seemed not only meant to provoke laughter, but further offered a public service of free disinfectant for any passers-by who required it.

Not all community play existed in the physical realm, of course. This early period of the pandemic also saw a rise in online group activities, such as through the use of newly developed community WhatsApp groups, as mentioned by numerous interviewees. Many families took to Zoom meetings, as well, with family quiz nights proving popular. In an interview conducted by Richard Bennett in June 2020, fifty-year-old Aberdeenshire-based former journalist and business owner, Kay Drummond, describes her own family’s quiz night:

We’ve set up since lockdown—my brothers and all their families—we have a weekly quiz. We have the Drummond family quiz. […] My sister-in-law and I, in Edinburgh, she and I talked about it first and we thought it’d be a good idea. […] It’s good fun. So 8:15. What we do is, do the Clap for Carers at eight o’clock and at 8:15 settle down with a drink and some nibbles and have a laugh with the family. (Drummond 2020)

Of particular interest here is the connection between Clap for Carers and the family’s quiz nights on Zoom. The former was a UK-wide campaign to publicly applaud the sacrifice of key workers, society’s most visibly vulnerable members, on Thursday nights during the first few months of the pandemic. The Clap for Carers campaign has been described as a government-approved attempt to ‘strengthen community cohesion and civic duty across different segments of British society’ (Farris, Yuval-Davis, and Rottenberg 2021: 285). This community cohesion was enhanced, not just cynically through official rhetoric but earnestly through vernacular play as well, with different households adding their own playful twist to the practice, whether through bagpipes, and pots and pans (Hall 2020) or, as witnessed in front of my block of flats in Leith, with a bubble wand, signs and whistles. In the quotation above, Drummond describes an intriguing concurrence of national, local and familial community building through play, with the national/local Clap for Carers segueing into a family quiz night, giving Thursday evenings a distinctive connotation of play and community bonding. In this way, one could consider that Clap for Carers functioned as a kind of government-sanctioned period of communal play, encouraging Kay’s family to extend that period to a full evening, with the online context allowing for different households in different parts of the country to come together and bond.

Other transitions between in-person play and online play were not always without friction. In an interview with Siân Burke, forty-two-year-old Kincardineshire-based educator Charlie Barrow and his daughter Olivia discussed difficulty in choosing between her inclinations for play through crafts and online play with her friends.

Though Charlie and Olivia agree that she very much enjoys creating crafts—and in the interview she describes making necklaces and charm bracelets amongst other creative outputs—she also mentions increasingly using various apps like Snapchat, Zoom and Messenger to see, speak to, and play with her friends in diverse ways, a phenomenon well-documented by Jackie Marsh (2014). The impossibility of physically being able to visit her friends places a greater emphasis on technological means of staying in contact, whether through special birthday Zoom quiz nights, as Olivia mentions at one point in the interview, or simply using Zoom to tell friends about new crafts she has created.

At the same time, some felt vulnerable to the stresses of community-building online events, resulting in a weariness with pressurized socializing and a world more and more dependent on online interaction. When discussing technology from his own perspective, Charlie states:

I think after a couple of weeks, after the novelty of using technology to stay in touch started to wear off, I really kind of got that Zoom fatigue. I really felt like I was spending a few hours a day looking at four-inch-tall portraits on the screen. And, you know, you have to focus on… quite an intense way. And I’d finish work and I’d just feel pretty drained. And then, ‘hey, we’re going to have a quiz with our friends at seven o’clock!’ And it just started to be not much fun. […] And if people start talking over the top of each other, it’s really, really, really difficult. So I’ve kind of stopped socializing as much as I did when we first went into lockdown and resorted to maybe phoning people a bit more rather than doing the video calls. (Barrow and Barrow 2020)

The beginning of lockdown brought not only governmental, community and familial pressure to socialize with others but pressure to socialize in particular ways through particular channels, such as through the Clap for Carers or via online means. Charlie’s switching to using the phone rather than using video calls reflects an apparent frustration with online technical issues, such as lag, that inhibit sociability, and also a reluctance to have to focus both visually and aurally via screen. In essence, play that seemed like a novel way of circumventing some of the physical limitations of lockdown became a chore. It lost its sense of fun. Charlie, as the player, became susceptible to social pressures, technological pressures and fatigue.

Charlie implies later in the conversation that this is maybe a generational difference, with his daughter seemingly able to play an online video game, watch television streaming services and speak to her friends on the phone all at the same time. Indeed, Olivia expands on this by discussing at some length how she plays and creates video games with her friends via an online platform, all while talking to them over the phone. She further explains that using the phone is faster than typing via the platform itself, allowing her and her friends a greater facility to focus on the game and conversation at the same time. Interestingly, this generational difference in online play is reflected in an interview by Mara Shea with fifty-two-year-old former small-business owner, Victoria Round:

I’ll be very glad to see the back of family Zoom calls. (Sighs) Where there’s so many people and so many squares and everybody either doesn’t talk or… oh, it’s just so unnatural. To be in a room and have an ordinary conversation will be wonderful with family members. […] But my son who’s a gamer says we should be using Discord […] because they’re much more intuitive because they don’t have delays […] Gamers have obviously been having conversations online for years, so they’ve got different technologies and it’s a much more natural conversation. (Round 2021)

Victoria’s revealing comments reinforce the idea that a generational technological gap significantly impacts the extent to which some people have been able to enjoy online play during the pandemic. In both Charlie’s and Victoria’s cases, the parent is aware of technologies that make online play more natural and sociable but there is a clear, if implicit, lack of enthusiasm to adopt them. As people playing in online contexts, they are vulnerable to the whims of technology and changing fashions that do not always suit them or conform to their personal interests or needs.

This gap has not existed across all forms of play, however, as discussed above with the intergenerational trail of affirmative signs on the Water of Leith. In some cases, play amongst one age group has been mirrored in another, with play amongst children inspiring adult play and vice versa. While online contexts proved to be less than fun for some participants, the classic creative practice of putting chalk to pavement thrived during the lockdowns. One early message I saw, written in chalk in front of someone’s doorway, simply said, ‘LOVE FROM NANA’, using a common nickname for ‘grandmother’. No doubt the grandmother who left the enormous chalk message could have phoned or maybe even used a video service to see her grandchild(ren) but evidently leaving a physical note had some importance for her. We can imagine that for the grandchild(ren), seeing a note in chalk, not far from other chalk drawings, might allow them to understand and enjoy the message in the context of their own chalk play. It also allowed the grandmother to put a physical marker at their door, to say ‘I was here and I love you’, even if she could not actually stay and see her grandchild(ren) due to lockdown restrictions. And it allowed her to leave a note that would greet the child(ren) every time they went out, presumably for their daily exercise. This longer-lasting, though still ephemeral, message, works temporally and spatially in a way that a Zoom quiz or Facetime call would have difficulty matching. As a public marker, it shows the poignant vulnerability of a grandmother who is both playing and lamenting at the same time.

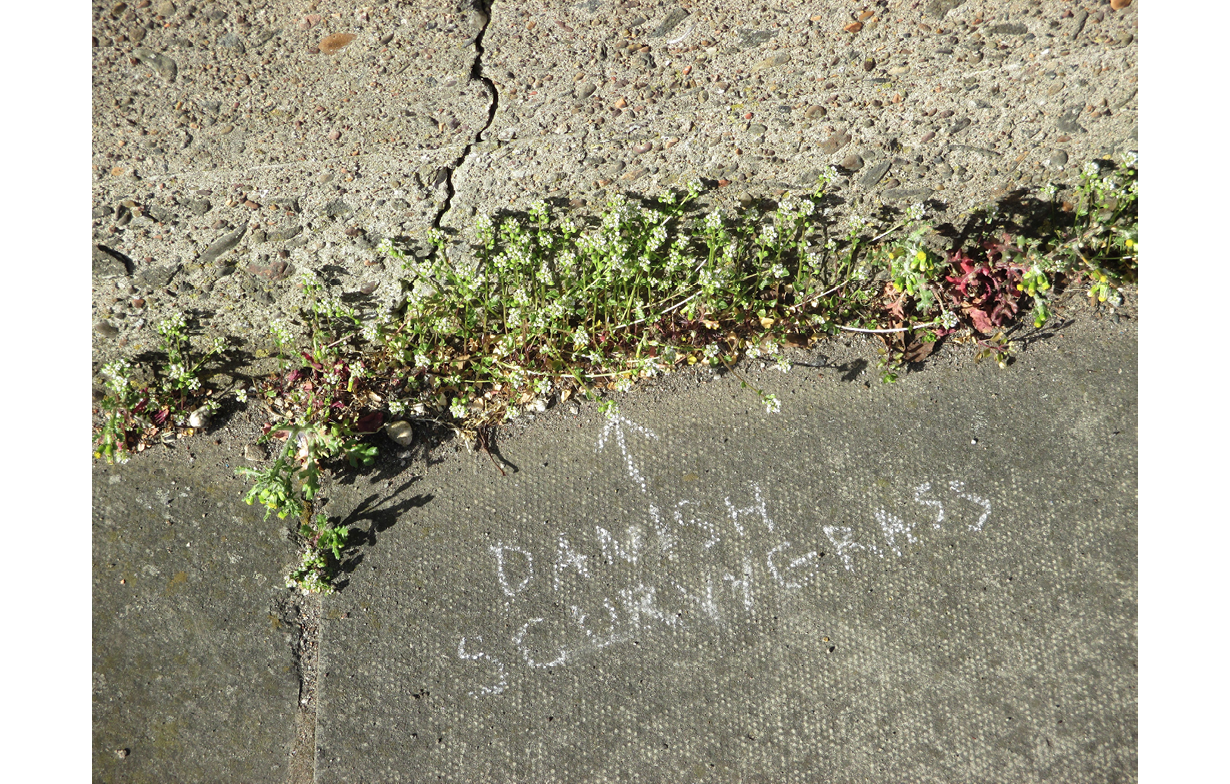

Some chalk messages had a more general public in mind for their audience, as seemed to be the case for a series of chalk writings I came across in my walks. One example, found on a seaside walking path near the breakwater in the Granton area of Edinburgh, was a chalk message with the words ‘DANISH SCURVYGRASS’ (Figure 11.4) and an arrow pointing to an almost imperceptibly small plant with tiny white flowers growing out of the concrete.

Figure 11.4 ‘Botanical Chalking, Granton, Edinburgh’, 13 April 2020

Photo © Nicolas Le Bigre, 2023, all rights reserved

During lockdown, when significantly fewer cars were on the road and many interviewees expressed a renewed awareness of the outdoors and the climate crisis, this small example of playful botanical education seemed particularly likely to have a receptive audience. Beyond audiences, the act of playfully naming and sharing knowledge has a personal benefit too. In an article on such botanical messages, The Guardian quoted a chalker (rendered anonymous due to the apparent illegality of chalking on pavements in the UK) saying,

Botanical chalking gives a quick blast of nature connection, as the words encourage you to look up and notice the tree above you, the leaves, the bark, the insects, the sky. And that’s all good for mental health. None of us can manage that much—living through a global pandemic is quite enough to be getting on with. But it’s brought me a great amount of joy. (Morss 2020)

During a period of susceptibility, not only to the coronavirus but also to climate change, using the tools of children’s schoolyard games to creatively disseminate information and change people’s perceptions of place and otherwise largely unnoticed plant life, brings joy to the chalker and potentially to those who come across it. This vulnerable lockdown period created a perfect moment for this kind of play to flourish and I saw several examples in different areas. This public identification of plants was roughly mirrored by a child in Leith Links who wrote, in large, carefully drawn lower-case letters in white chalk, the word craobh (‘tree’ in Gaelic) on the pavement in front of a large tree. We might imagine a child learning Gaelic using this familiar writing implement as a way of marking and remembering new vocabulary but also perhaps using it to share this Gaelic word with others. The appearance of the friendly letters offered not only the opportunity to smile—much needed during the lockdowns—but also educated non-Gaelic speakers like me.

Other chalk messages invoked a need to let go and find exuberance during what was a tough time for children and adults alike. Importantly, the play encouraged by these creations was always individual as opposed to group play, reflecting one of the more serious changes for children during the pandemic. Doug Haywood, a forty-six-year-old Aberdeen teacher, in an interview with David Francis, describes a colleague who was teaching at a hub for key workers’ children early in the pandemic:

And it’s tricky, you know, trying to get kids—constantly reminding them to socially isolate. She was describing four girls that had been playing together. And, you know, she’s saying to them, ‘Remember, you’ve got to stay two metres apart, come on, you can do this’. And literally thirty seconds later she’s saying the same thing to the same girls again because, you know, they want to play. (D. Haywood 2020)

There is a difficult balance here between the children’s natural urge to play together and the very serious dangers of the virus to students and teachers alike. In the chalk drawings I came across, though, children came up with creative solutions that allowed them to have fun while playing in a distanced way, thus minimizing susceptibility to a viscerally difficult-to-understand invisible virus of which they had been taught to be wary. One of my favourite examples of such a chalk creation—in the Leith Fort area of Edinburgh—was a small colourful circle with sun rays extending out on all sides and four stick figures inside, with the invocation, ‘STEP INSIDE AND WIGGLE’. The circle was big enough for one person but anyone standing beyond the rays would be roughly far enough to be properly distanced. Many chalk drawings like this provoked physical play of some kind, as with the well-known hopping game known as, among other things, Peevers or Hopscotch (Ritchie 1968; Opie and Opie 1997; Roud 2011). The craving for physical play and bodily expression—whether through wiggling (and no doubt giggling) or through hopping—was evident across the streets of Scotland during the lockdowns. One hopscotch creation I witnessed in the northern section of Starbank Park in Newhaven, Edinburgh, perilously ran the length of a steep and curving walking path from the top of a hill all the way to the bottom. Its successful completion seemed an impossibility but part of the fun must have been in creating an unachievable challenge, seemingly an unintentional metaphor for our susceptibility to the limits imposed upon us during lockdowns and our efforts to redefine those limits.

Creating challenges during the lockdown was not only the recourse of children, and their creation and attempts at succeeding at them seemed to both adults and children an important way to keep mental awareness and energy levels up while also implicitly helping to cope with the restrictions. Kay Drummond sent in several videos of the garden races and rainy-day singing contests (among many other challenges) that she set up for her two enthusiastic sons. Looking back on that first summer of the pandemic during the following winter, she told Richard Bennett:

So I would say that it’s as much about setting yourselves little goals, and I feel… I know what we did in the summer was set a lot of goals and feel that we were out in the garden achieving this, that and the next thing, and getting the boys, you know, keeping the boys’ energy levels up as well as being active. (Drummond 2021)

The implicit challenge for Kay here is being a parent and having to come up with and follow through on different games, contests and tactics to keep her children engaged, healthy and content. There is also an important element of bonding between parent, child and siblings during a potentially very frightening period for everyone. Charlie Barrow and his daughter Olivia also responded to the crisis by creating challenges for themselves, in their case by sending different videos every week to distant family members demonstrating knot-tying techniques. As the weeks went by and the lockdown continued, the videos took a more playful, but darker, tone, culminating in an impressively unnerving homage to David Lynch’s television series, Twin Peaks (Barrow 2020). Whereas earlier videos demonstrated knot tying—a simple challenge with a clear outcome—the latter film spookily turned this innocent activity on its head, with an ambiguous, uneasy and unresolved conclusion. This seemingly reflected a pandemic with no clear end point or solution in sight, highlighting our collective vulnerability in the context of an unknowable future.

For playful adults, limit-testing challenges in lockdown contexts often manifested themselves through trepidatious but thrilling rule-breaking trickery, real or imagined. One interviewee in her seventies, whom I have left unnamed, describes three different instances of rule breaking: one in which she meets a friend at the gate of a cemetery ‘quite by chance’ which does her ‘so much good. Just to see another person’. In the second instance, she describes rehearsing the story she will tell police if she is stopped while illegally walking her dog at the beach. In her words, ‘If you’re going to break one rule you’re going to break another one, aren’t you?’ Here she seems to be almost playfully challenging the police more than herself. In the third instance, she recounts the law-skirting of a friend of hers:

I spoke to a dear, dear friend the other day. I’ve known her for so long. She’s 93 and she said, ‘Oh my darling, I’m breaking all the rules. All my friends come round once a week for cocktail parties’. And she said, ‘What can old women do but break some rules?’ (Laughs) I thought it was lovely.

The anxiety in the interviewer’s voice is palpable, and she exclaims ‘Oh, no!’ and nervously asks, ‘So they actually do come round?’, only for the interviewee to quickly confirm, ‘Yes, they come round to her flat and they have cocktail parties!’ Nevertheless, the interviewer senses the excitement her contributor feels and at one point asks, ‘And the breaking the rules, did it make you feel a little bit Famous Five-ish?’, in reference to the British children’s adventure novels. The answer comes quickly: ‘Super! You just felt so bad!’ There is clear playfulness in her descriptions of her mischievous forays and those of her friends. When describing an instance of getting closer than two metres to a friend of hers, she sarcastically exclaims, ‘Oh, gosh, we came a bit too close then!’ Vulnerability, both legally and in terms of the virus, seems to be the source of the fun here, allowing her to push herself beyond acceptable limits and play the trickster in the face of authority. Beyond fun and playfulness, though, she indicates that breaking the rules is necessary for her mental and physical wellbeing. Though she is vulnerable in the wider world, whether to authority or the virus, the vulnerability that comes with solitude and isolation is pointed, and play and trickery allow her to overcome at least one form of vulnerability during the pandemic.

As Kay Drummond says while reflecting on the garden contests described above and the realities of a snowy winter and renewed lockdown:

This time I think it’s as much about just making sure that everybody is, you know, handling it emotionally and because you haven’t got the same outlets as you had before. (Drummond 2021)

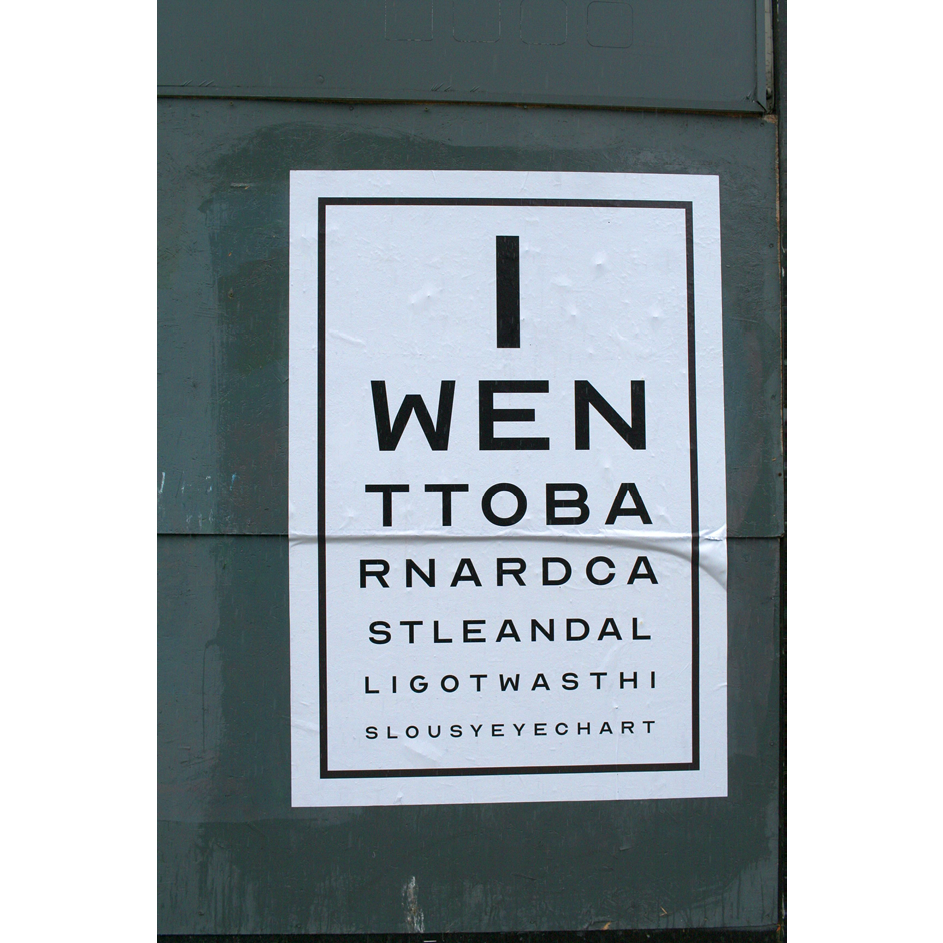

Without those outlets—whether achieved in one’s garden with family or through playful rule-breaking in the wider world—it is clear that many people felt increasingly vulnerable to discomfort and restlessness as the pandemic continued. Accompanying those feelings of anxiety was growing awareness of the seeming hypocrisies in the UK government’s management of the pandemic. Towards the end of spring 2020, newspapers began reporting that Dominic Cummings, then Chief Advisor to the Prime Minister, broke lockdown rules by driving to his parents’ farm in Durham, all while suffering from COVID-19. On his return trip to London, he and his family drove to the tourist attraction, Barnard Castle, purportedly so that he could test his eyesight and ensure that he was well enough to drive (Fancourt, Steptoe, and Wright 2020). In addition to this, perhaps ironically, being an example of bureaucratic rule-breaking and play (Martin et al. 2013: 569), this resulted in a number of angry and mocking examples of street art, indicating that cynicism and frustration were manifesting themselves in playful forms in the public sphere as well. One example, wheat-pasted onto a wall of a building on Leith Walk, was designed like an optician’s eyechart—playing with Cummings’ excuse of testing his vision. With words running into each other and each line getting progressively smaller, the text read, ‘I went to Barnard Castle and all I got was this lousy eyechart’ (Figure 11.5).

Figure 11.5 ‘Sardonic Eyechart, Leith, Edinburgh’, 10 June 2020

Photo © Nicolas Le Bigre, 2023, all rights reserved

As the general mood started to change in Scotland, and seemingly the UK more generally, many examples of play began to take a more cynical air. This temporal and contextual shift is neatly summarised by Victoria Round, who breaks down the pandemic while reflecting on its various stages:

It’s sort of a gritting your teeth stage now, isn’t it? It’s not novel. It’s not… We had the novelty. We had the ‘all pulling together’ and feeling of community. Then we had everyone sort of desperate and turning on each other, and now it’s just gritting your teeth, getting on with it. (Round 2021)

The ‘turning on each other’ stage seemingly refers to this period a few months in, with government scandals and people phoning the police on their neighbours to report lockdown breaches of various kinds. Round’s description of ‘gritting your teeth’ complements Drummond’s testimony above, from an interview made in the same month, that ‘handling it emotionally’ was key in that winter period.

Others were cynical, at least of government responses, from an earlier stage. Charity worker Myshele Haywood, in response to a query from interviewer Claire Needler about making rainbows and other ‘light-hearted’ things, says:

Oh Jesus, no. Haven’t done the rainbow thing. Haven’t clapped for the NHS because that’s just such bullshit. I will work for NHS workers to get decent pay, thank you very much. They don’t need my applause. They need my activism. They need me to not vote Tory. […] What else? Fun things. I am somebody that doesn’t really do fun very well. (Laughter) I tend to try to do things with a purpose. Well, I crocheted a rainbow tea cosy for my husband because he was joking […] ‘Oh, I need a tea cosy’. I was like, ‘Oh, do you want me to crochet you a rainbow tea cosy?’ He was like ‘Yeah, yeah, I do, I do’, so. Okay, Google how to make a tea cosy. So that was a fun thing. (M. Haywood 2020)

But despite profound cynicism towards some of the communal displays of support for key workers, who Myshele identifies as being vulnerable to destructive government policies towards the NHS, it is important to keep aware of the nuance in Myshele’s descriptions. People have had layered interactions with the pandemic, with multiple feelings co-existing concurrently. Here, Myshele’s early cynicism is accompanied by an earnest expression of play in a marital context, play which is possible due to time afforded by the lockdown context. That this moment of play is facilitated by learning online how to crochet a tea cosy also perfectly reflects the continuous strands of heightened physical-online hybridity that have existed from the beginning of the pandemic. Though we might legitimately consider the pandemic and its play temporally through various stages of changing public attitudes, it is also important to remember that individuals’ own responses to the pandemic and resultant susceptibilities were not necessarily limited to prevailing sentiments at any one stage.

Group responses did, however, tend to follow more obvious stages, as seen by rainbows and the Clap for Carers, public cynicism at government scandals and lockdown breaches, and eventually varying responses to vaccines and related mandates. By the second summer of the pandemic, I was living in Aberdeen, where I began documenting stickers decrying the arrival of vaccinations. Some of these stickers were carefully designed, making playful references to mid-century American advertising imagery. They featured healthy white faces—the kind that erstwhile would have hawked cigarettes through misleading statements—with the implication that the government, the media and the vaccine producers were trying to promote false hope to line their pockets or even poison the populace. There were a number of such stickers, mostly sourced from one online group, whereby individuals could download designs and print them out using label machines. Surprisingly to me, online posts on the group’s public social media channels indicated a genuine sense of play and challenge in encouraging new people to join and photograph their stickers in notable locations.

Others, aware of how susceptible people can be when confronted with misinformation, and frustrated by the brazenness of the stickers, equally responded through play. One sticker, promoting a website with various discussions of conspiracy theories, pandemic-related or otherwise, was modified with the addition of another sticker placed directly in its centre, simply stating ‘citation needed’ (Figure 11.6).

Figure 11.6 ‘Ironic Sticker Request, Aberdeen’, 26 March 2021

Photo © Nicolas Le Bigre, 2023, all rights reserved

In a time of division along political lines and myriad beliefs relating to personal and public health, these street sticker battles reflect serious vulnerabilities of everyday life, whether through fear of government-imposed mandates or concern for the effects of misinformation. Importantly, play allows the players to both express these vulnerabilities and deftly navigate around them.

Conclusion

This intentional or unintentional effect of play, in which players both express vulnerability and help soften or circumvent it, is at the heart of the examples described above. Play, whether online or offline, shows the vulnerability of its players. We can see above that for some, play reveals a fear of the potentially ephemeral nature of newfound community, while for others there is frustration with community that is imposed upon them. There is a lament for the loss of physical contact and regret for generational disadvantages in online contexts. Some demonstrate a fear of an unknown future, while others demonstrate exasperation with the limits placed upon them. But while in each of these cases players use play to delineate the boundaries of their vulnerabilities, they also use play to better protect those points of susceptibility. Whether through clapping, crocheting, film making, chalking, gift giving, sticker sticking, video game playing, educating, sign making, statue decorating or other novel or well-practised forms of play, players are able to understand their limitations while also slowly expanding their possibilities. And if for me this project and this chapter were forms of play, of collecting interesting items and arranging them for display, they also helped demarcate the limits of my work, pointing to vulnerabilities which the project did not clearly pick up on. One of the most poignant pandemic-related sights I encountered was when my wife and I moved back to Aberdeen mid-pandemic. Spray-painted on the wall adjacent to our home were the words, ‘FUCK LIFE COVID 19 WANTED’. This served as an inescapable reminder of the enormous societal inequities amplified during the pandemic, whether due to mental and physical health difficulties, lack of green space, inability to access the internet, domestic abuse, ableism and racism on individual and structural levels, and so on. Though many of these themes were picked up on in contributions and discussed in interviews, the very nature of a university-based, online archival project meant that the voices of those most vulnerable were largely not included. By giving a number of examples of vulnerability and play during the pandemic, and by presenting the words of some of the players themselves, however, I hope to give valuable ground-level understandings to the notion that vulnerability and play are intertwined. Like all forms of folklore, people’s fears, hopes, anxieties, dreams, values and levels of privilege have shaped what and how they have played and to what extent they have been able to play. Vulnerable play is simply play in its most honest form, and play—whether communal, individual, ethnographic, earnest, mischievous, or cynical—has sustained us during the pandemic. However the pandemic finishes, we can rest assured that play and its inherent vulnerabilities will accompany it till the very end.

Works Cited

Anonymous. 2020. Interviewed by Natalie Brown, 13 May, Lockdown Lore Collection Project, Elphinstone Institute Archives, University of Aberdeen

Barrow, Charlie. 2020. Personal communication. 4 May

Barrow, Charlie, and Olivia Barrow. 2020. Interviewed by Siân Burke, 19 May, Lockdown Lore Collection Project, Elphinstone Institute Archives, University of Aberdeen

Drummond, Kay. 2020. Interviewed by Richard Bennett, 8 June, Lockdown Lore Collection Project, Elphinstone Institute Archives, University of Aberdeen

——. 2021. Interviewed by Richard Bennett, 2 February, Lockdown Lore Collection Project, Elphinstone Institute Archives, University of Aberdeen

Fancourt, Daisy, Andrew Steptoe, and Liam Wright. 2020. ‘The Cummings Effect: Politics, Trust, and Behaviours during the COVID-19 Pandemic’, Lancet, 6 August, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31690-1

Farris, Sara, Nira Yuval-Davis, and Catherine Rottenberg. 2021. ‘The Frontline as Performative Frame: An Analysis of the UK Covid Crisis’, State Crime, 10: 284–303, https://doi.org/10.13169/statecrime.10.2.0284

Gillis, Ben. 2011. ‘An Unexpected Font of Folklore: Online Gaming as Occupational Lore’, Western Folklore, 70: 147–70

Goldstein, Diane. 2004. Once upon a Virus: AIDS Legends and Vernacular Risk Perception (Logan: Utah State University Press)

Hall, Jamie. 2020. ‘Clap for our Carers: North-East Residents Pay Tribute to NHS Staff’, Press and Journal [Aberdeen], 10 April, https://www.pressandjournal.co.uk/fp/news/aberdeen-aberdeenshire/2138533/clap-for-our-carers-north-east-residents-pay-tribute-to-nhs-staff/

Harding, Sarah. 2020. ‘Daily Exercise Rules Got People Moving During Lockdown—Here’s What the Government Needs to Do Next’, The Conversation, 5 August, https://theconversation.com/daily-exercise-rules-got-people-moving-during-lockdown-heres-what-the-government-needs-to-do-next-143773

Haywood, Doug. 2020. Interviewed by David Francis, 13 May, Lockdown Lore Collection Project, Elphinstone Institute Archives, University of Aberdeen

Haywood, Myshele. 2020. Interviewed by Claire Needler, 12 June, Lockdown Lore Collection Project, Elphinstone Institute Archives, University of Aberdeen

Le Bigre, Nicolas. 2020. ‘Documenting Creative Responses to the Pandemic’, FLS News, 91: 15–16

Lindahl, Carl. 2018. ‘Dream Some More: Storytelling as Therapy’, Folklore: 221–36, https://doi.org/10.1080/0015587X.2018.1473109

Lindgren, Anne-Li. 2017. ‘Materializing Fiction: Teachers as Creators of Play and Children as Embodied Entrants in Early Childhood Education’, International Journal of Play, 6: 150–65, https://doi.org/10.1080/21594937.2017.1348317

Marsh, Jackie. 2014. ‘The Relationship between Online and Offline Play: Friendship and Exclusion’, in Children’s Games in the New Media Age: Childlore, Media, and the Playground, ed. by Andrew Burn and Chris Richards (Farnham: Ashgate), pp. 109–32

Martin, Andrew W., et al. 2013. ‘Against the Rules: Synthesizing Types and Processes of Bureaucratic Rule-Breaking’, Academy of Management Review, 38: 550–74, https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2011.0223

Morss, Alex. 2020. ‘“Not Just Weeds”: How Rebel Botanists Are Using Graffiti to Name Forgotten Flora’, The Guardian, 1 May, https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2020/may/01/not-just-weeds-how-rebel-botanists-are-using-graffiti-to-name-forgotten-flora-aoe

Nicolaisen, W. F. H. 1992. ‘Humour in Traditional Ballads (Mainly Scottish)’, Folklore, 103: 27–39, https://doi.org/10.1080/0015587X.1992.9715827

National Records of Scotland. 2022. ‘Deaths Involving Coronavirus (COVID-19) in Scotland’, https://www.nrscotland.gov.uk/statistics-and-data/statistics/statistics-by-theme/vital-events/general-publications/weekly-and-monthly-data-on-births-and-deaths/deaths-involving-coronavirus-covid-19-in-scotland

Opie, Iona, and Peter Opie. 1997. Children’s Games with Things (Oxford: Oxford University Press)

Oram, Richard. 2007. ‘“It cannot be decernit quha are clean and quha are foulle”: Responses to Epidemic Disease in Sixteenth- and Seventeenth-Century Scotland’, Renaissance and Reformation, 30.4: 13–39

Prime Minister’s Office. 2020. ‘Prime Minister’s Statement on Coronavirus (COVID-19): 23 March 2020’, https://www.gov.uk/government/speeches/pm-address-to-the-nation-on-coronavirus-23-march-2020

Ritchie, James T. R.. 1965. Golden City (London: Oliver and Boyd)

Round, Victoria. 2021. Interviewed by Mara Shea, 30 January, Lockdown Lore Collection Project, Elphinstone Institute Archives, University of Aberdeen

Robertson, D. H. 1862. ‘Notes of the “Visitation of the Pestilence” from the Parish Records of South Leith, A.D. 1645, in Connexion with the Exaction of Large Masses of Human Bone during Drainage Operations at Wellington Place, Leith Links, A.D. 1861–2’, Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, 4, 392–95, https://doi.org/10.9750/PSAS.004.392.400

Roud, Steve. 2011. The Lore of the Playground: The Children’s World, Then and Now (London: Arrow)

World Health Organization. 2022. ‘14.9 Million Excess Deaths Associated with the COVID-19 Pandemic in 2020 and 2021’, https://www.who.int/news/item/05-05-2022-14.9-million-excess-deaths-were-associated-with-the-covid-19-pandemic-in-2020-and-2021

1 All mentions of the project must include thanks to my wife, Jodi Le Bigre, and my colleagues at the Elphinstone Institute, University of Aberdeen, Simon Gall, Alison Sharman, Carley Williams, Sheila Young, Frances Wilkins and Thomas A. McKean. Special thanks are due to the dedicated volunteer interviewers: Emma Barclay, Richard Bennett, Natalie Brown, Siân Burke, Mary Cane, David Francis, Claire Needler, Vera Nikitina, Laurie Robertson, Mara Shea, Eleanor Telfer and Ryo Yamasaki.

2 These can be accessed by contacting the Elphinstone Institute Archives (email: elphinstone@abdn.ac.uk).