12. How Young Children Played during the Covid-19 Lockdown in 2020 in Ireland:Findings from the Play and Learning in the Early Years (PLEY) Covid-19 Study

© 2023, Suzanne M. Egan et al., CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0326.12

Introduction

The Covid-19 measures put in place by governments around the world to restrict the movement of people and limit the spread of the virus have also impacted on children’s play. The importance of play in children’s lives has been well documented and research shows that it plays a role in all aspects of development including physical, cognitive and socio-emotional development (e.g. Ginsburg 2007: 182, Fisher et al. 2008: 306, Howard and McInnes 2013: 738). Different types of play have been classified, as have the different ways that children can learn and develop through play (e.g. Parten 1932: 249, Whitebread et al. 2012: 31). This chapter will examine some key findings on changes in young children’s play in an Irish context based on parental responses gathered during the first Covid-19 lockdown in spring 2020.

The evidence on children’s play during the pandemic to date suggests that globally there have been a number of changes (e.g. Barron et al. 2021: 372; Moore et al. 2021: 4). New research is still emerging but it seems that commonalities across countries during lockdowns included increases in time spent on screens and on indoor play, and decreases in physical activity and outdoor play. A cross-country comparative study of children’s indoor play during the lockdown indicated many similar impacts on play behaviours and activities, irrespective of country, specific cultural factors or restrictions in place (Barron et al. 2021: 375). Children’s development and how they play does not operate in a vacuum as children are influenced by the world around them and often use play to make sense of their experiences (e.g. Hirsh-Pasek, Singer, and Golinkoff 2006: 39; Hayes, O’Toole, and Halpenny 2017: 88).

According to an article on the World Economic Forum, ninety-nine percent of the world’s children have lived with restrictions on movement and interactions because of Covid-19 (Fore and Hijazi 2020). The pandemic disrupted every aspect of children’s lives, including their health, development, learning and behaviour, their families’ economic security, their protection from violence and abuse, and their mental health. Recent research studies have also borne this out (e.g. Almeida et al. 2021: 413; Egan et al. 2021: 925; López-Aymes et al. 2021: 1, Thorell et al. 2021: 649; Thorn and Vincent-Lancrin 2022: 383). Under Article 31 of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNICEF 1989), children have the right to play, although this is often a neglected right (Shakel 2015: 48).

Covid-19 Restrictions in Ireland in 2020

In the Irish context, on 12 March 2020 the Government announced with one day’s notice the closure of all schools, preschools, crèches, colleges and universities. This was extremely disruptive to all parents, children and families—with national restrictions announced later that month impacting all citizens. The Irish government directed everyone to stay at home except in specific circumstances (e.g. travel to and from essential work, shopping for food, attendance at medical appointments), and to practise social distancing (i.e. stay two metres apart in all public spaces). This resulted in the closure of all non-essential businesses.

During the lockdown, schools turned to online learning as much as possible. However, there was significant variation in access to digital home schooling and to electronic devices (e.g. Egan and Beatty 2021: 8). Many parents were faced with the care and education of their young children, while juggling working from home. These effects were felt globally, with the lives of young children changing considerably during this time. Playgrounds were also initially closed in Ireland. Adults and children could leave their homes only for brief physical exercise, only within two kilometres of their home, and households were not permitted to mix (RTÉ News 2020). Most television and radio coverage had extensive reporting of the crisis as effects of the restrictions and lockdown impacted on children and adults. Non-essential travel in Ireland was extended to five kilometres on 1 May and to twenty kilometres on 8 June.

In order to explore the effects of the lockdown on children’s play, learning and development during this difficult time, we designed and ran an online survey to capture the experiences of families with young children aged between birth and ten years old. This built on the findings of a previous, similar survey conducted by members of the Cognitive, Development and Learning Research Lab in Mary Immaculate College, Ireland, during 2019 (Egan, Hoyne, and Beatty 2021: 224). The Play and Learning in the Early Years (PLEY) Covid-19 survey was open to parents during late May and early June 2020, approximately two months into the lockdown in Ireland. To facilitate comparison, many questions on the survey (e.g. regarding daily and weekly frequencies of various play activities) were drawn directly from the national birth cohort study Growing Up in Ireland (McCrory et al. 2013: 2; Williams et al. 2019: 10) and previous research (e.g. developmental scales; Goodman 1997: 582). Some questions were also adapted from previous research while others were developed specifically for the PLEY Covid-19 survey (e.g. questions relating to the impact of the COVID-19 restrictions). The survey questions and procedures were approved by the Mary Immaculate College Ethics Committee.

The Play and Learning in the Early Years (PLEY) COVID-19 Survey

The recruitment phase for the survey lasted two weeks, from 21 May through June 2020, during which time the online Play and Learning in the Early Years (PLEY) Covid-19 survey was open to participants. Parents with young children were recruited through newspaper advertisements and also through social media platforms, including via Twitter and Facebook. Information about the study, including a link to the survey, was shared with parenting networks, early years organizations and centres, schools and parents of young children who are active on social media, who in turn shared this information with their contact networks by retweeting, posting or forwarding information. Information about the survey and a link to it was also available on the Government of Ireland’s Parents Centre webpage while the survey was open and it was also shared on social media by the Government of Ireland’s Department of Children and Youth Affairs. All materials and procedures were approved by the institutional ethics committee.

In total, 564 parents responded to the survey. However, forty-seven responses were excluded from the analysis of the data because they only completed the initial demographic questions, while a further eleven participants had children outside of the target age range of ten years or younger. The final sample consisted of 506 participants (92.9% mothers, 5.9% fathers, 1.2% other) with a mean age of 40.36 years (SD = 4.81). The participants’ children had an average age of 6.41 years (SD = 2.44), ranging from 1 to 10 years (49.8% male, 49.6% female and 0.6% unspecified). Most children had siblings (82.8%) and were breastfed (71.3%).

The majority of participants (95.8%) were from Ireland, with the remaining participants being from the United Kingdom (2%) or other parts of the world (1.2%). Most parents worked full time (61.1%) or part time (22.1%), with others looking after family or on leave (14.7%). Most parents (85.7%) indicated that, because of the Covid-19 crisis, they had changed to working from home (71.7%) or were temporarily not working due to business closure (11.8%). The majority of the sample were well-educated with 84.4% holding a college-level degree or postgraduate qualification. All participants completed the PLEY Covid-19 survey via Qualtrics software. After expressing initial interest in the survey by clicking on the advertised link, participants were provided with additional detailed information about the survey and what was involved before giving their informed consent to take part.

The survey took approximately twenty minutes to complete and consisted of three sections asking parents about their children’s play, learning and development. The first section of the survey explored the impact of the Covid-19 restrictions on children’s play and learning. Parents were asked to indicate approximately how much time their child spent on an average weekday and an average weekend day over the previous two months playing with toys and games, reading and story time, outdoor play, and on screens. The final question in this section asked parents if their child had brought information about the virus or restrictions into their play (e.g. Doctors and Nurses) and particularly if they had brought it into chasing games (e.g. Tag/Tig). Responses to this section of the survey are the focus of the results reported below.

The second section of the survey measured aspects of children’s cognitive and socio-emotional development using standardized scales. These included the Attentional Focusing subscale from the Children’s Behaviour Questionnaire (Rothbart et al. 2001: 1396) and the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (Goodman 1997: 581). The third and final section asked parents about the physical and social factors that influence their child’s play and learning activities (e.g. play resources at home; parents’ beliefs about playtime experiences (Fogle and Mendez 2006: 509), influences of siblings, peers and parents; supports and barriers to play; experiences in the child’s home). This section also recorded information about the weekly frequency of various play activities (e.g. playing with blocks or with puzzles) and some of this information is also reported below. Parents completed most of the demographic questions first, followed by the questions about the impact of Covid-19 on play and learning. Subsequently, they completed the measures of child development and finally, the more detailed questions about influences on play, other than the Covid-19 restrictions (e.g. play resources in the home).

The Home Play Environment in Ireland during Lockdown

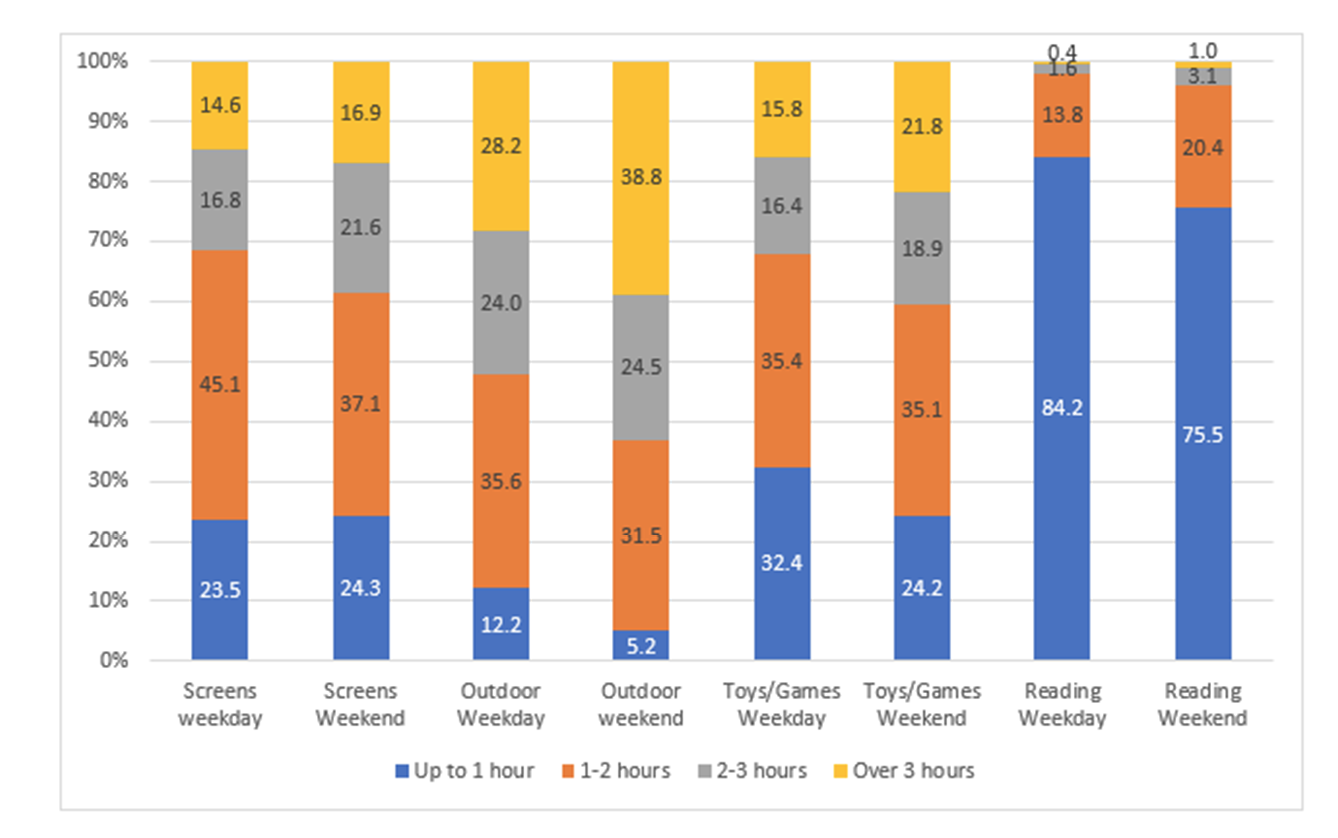

The findings of the survey shed light on the types and amounts of play that young Irish children engaged in during the first lockdown. As Figure 12.1 below shows, most children engaged in up to an hour of reading/story time each day and spent more than one hour playing with toys and games, playing outdoors or on screens. The figure also shows some changes in the amount of time spent in various play activities between weekdays and weekends, with children on average spending more time in each type of play at the weekends than on a weekday. This is particularly evident for outdoor play where 38.8% of children were spending over three hours per day on this type of play at the weekend, compared with 28.2% on a weekday.

Figure 12.1 Percentage of children in each time category for each activity on a typical weekday and weekend day

Created by Egan et al. 2022, CC BY-NC 4.0

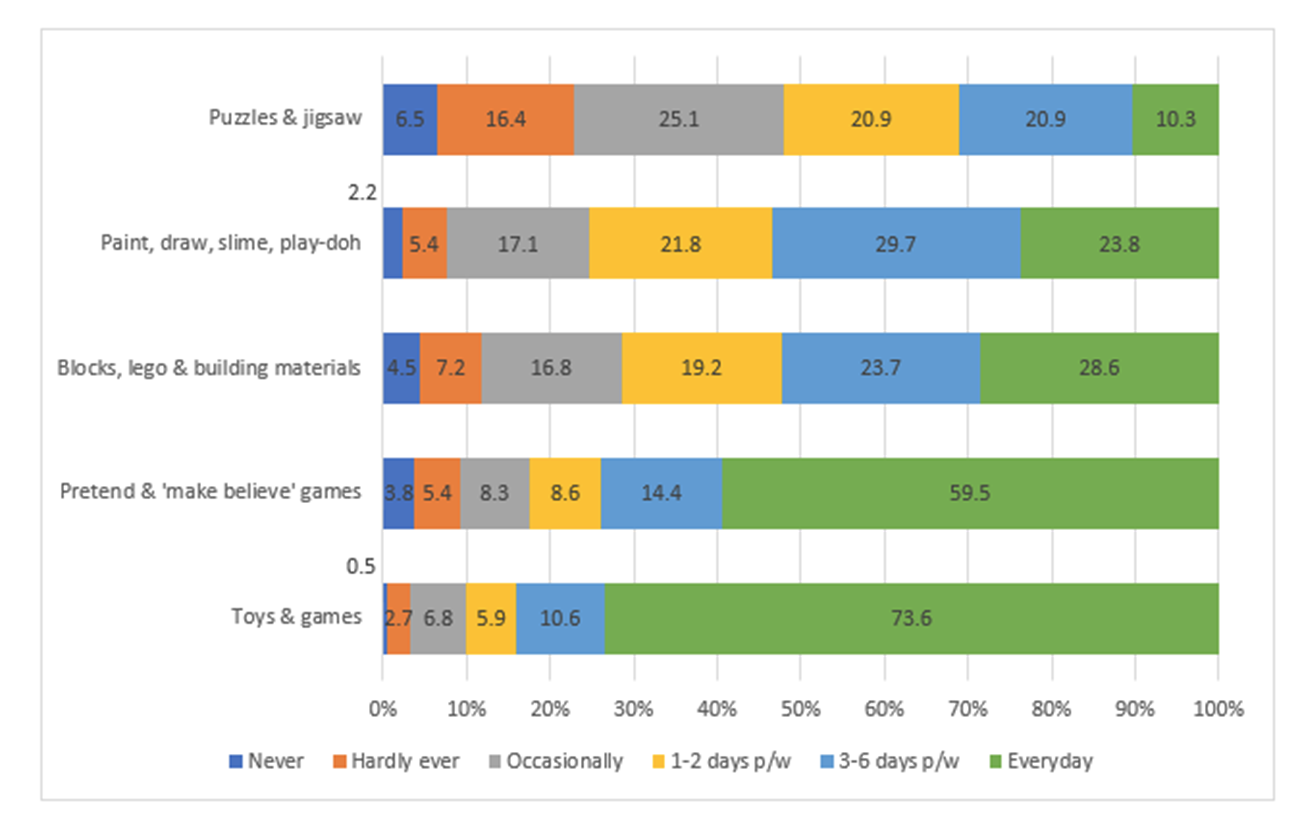

Figure 12.1 also shows that over two thirds of children played with toys or games for over an hour per day, both on weekdays (67.6%) and weekends (75.8%). Another question on the survey sheds light on the types of toys and games the children engaged with and how often. Figure 12.2 below suggests that over half of the children in the sample engaged in construction and creative play multiple times per week (three to six days per week or every day), using blocks, LEGO or building materials (52.3%) or with Play-Doh, slime, painting or drawing (53.5%). Pretend and make-believe play was also very popular with 73.9% of children, who engaged in this activity at least three days per week.

Figure 12.2 Percentage of children engaged in various play activities during the first two months of lockdown in 2020 in Ireland

Created by Egan et al. 2022, CC BY-NC 4.0

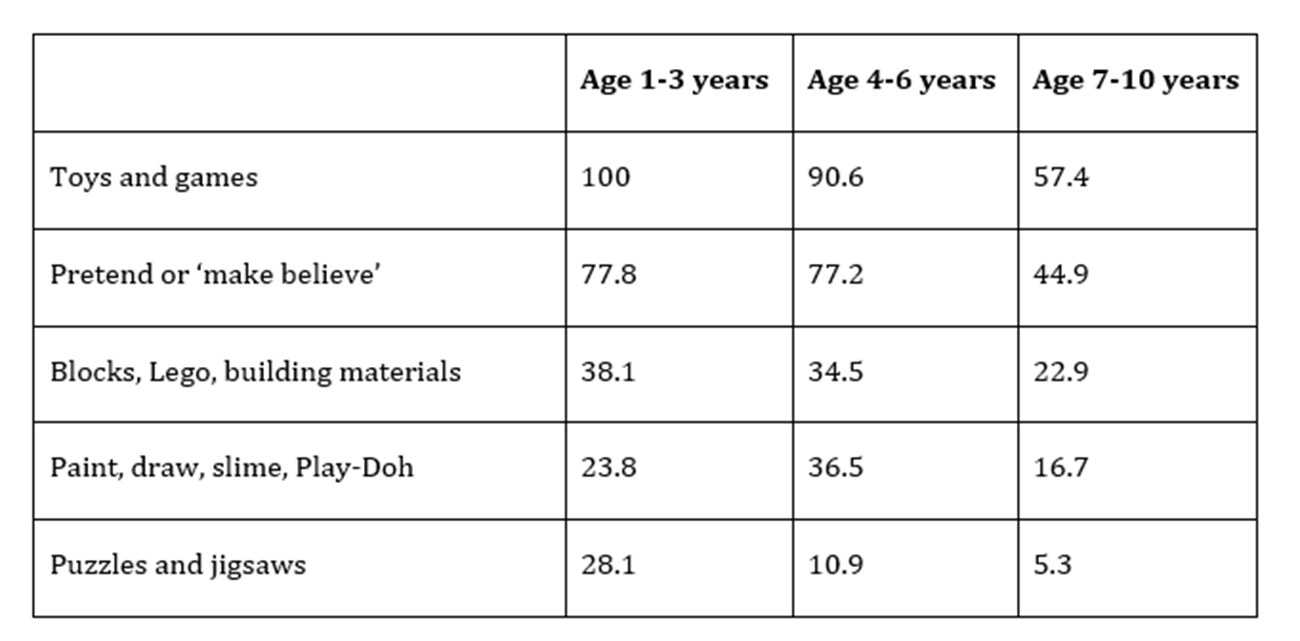

However, the rates of engagement in various play activities were influenced by the age of the child. As Figure 12.3 shows, older children aged from seven to ten years were less likely to engage in each of the various activities on a daily basis, compared with those aged from one to three years or from four to six years. For example, nearly all of the children under seven years of age played with toys and games every day during lockdown, while only fifty-seven percent of children aged seven years or older engaged in this type of play daily. Additionally, approximately seventy-seven percent of the under sevens engaged in pretend or make-believe play every day, in comparison to forty-five percent of children aged seven years or older.

Figure 12.3 Percentage of children engaged in various activities ‘every day’ by age group

Created by Egan et al. 2022, CC BY-NC 4.0

Parental Beliefs about Play and Engagement in Play Activities

Parents were asked to indicate their level of agreement with various statements regarding their beliefs about play. Nearly all parents indicated that there were plenty of toys, pictures and music (96.5%) in their home for their child, as well as plenty of books (96.6%), with ninety-one percent indicating their child had over twenty books (80.4% indicated they had over thirty children’s books). Most parents also somewhat agreed or strongly agreed with statements that there were lots of creative activities going on in the home (75.7%), that it was an interesting place for their child (86.7%) and that activities were provided that were just right for their child (77.2%), suggesting most parents viewed their home as a rich play environment.

Parents also indicated that they valued play for socio-emotional and cognitive development, with most agreeing that play can help their child develop social skills (97%), improve their language and communication skills (98.6%) and help develop better thinking abilities (96.5%). Furthermore, 95.5% of parents indicated that playing together helps build a good relationship with their child. Parents also indicated that playing was fun, with most agreeing that play is a fun activity for their child (97.7%), they have a lot of fun when they play with their child (90.5%), their child has fun when they play together (95.3%) and that it is important for them to participate in play with their child (85.1%).

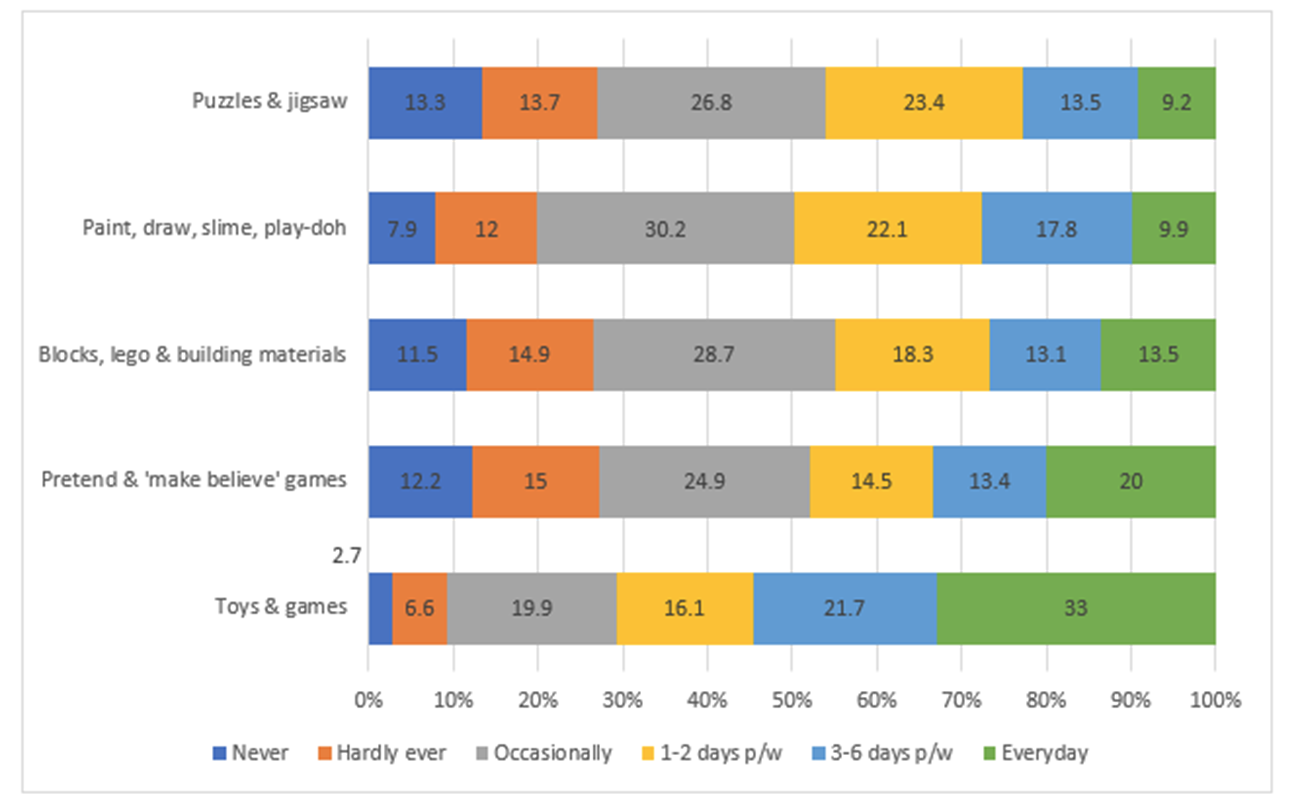

Figure 12.4 below shows the frequency with which parents reported playing with their child during various activities, with thirty-three percent playing with toys and games with their child every day. The findings indicate that for the various activities listed, approximately half of parents engaged in these activities with their child on at least a weekly basis, while the other half ‘never’, ‘hardly ever’ or only ‘occasionally’ engaged in these activities. There was little difference in how often the parents engaged in the different types of activities whether it involved play with blocks, Play-Doh or jigsaws. The most frequent type of daily play parents engaged in was with toys and games (thirty-three percent of parents did this everyday) followed by pretend or make-believe play (twenty percent of parents did this every day).

Figure 12.4 Percentage of parents who engaged with their child in various play activities during the first two months of lockdown in 2020 in Ireland

Created by Egan et al. 2022, CC BY-NC 4.0

Inclusion of the Virus and Restrictions in Play

Approximately one third of parents (34%) indicated that their child had included information about Covid-19 in their play, with reference to the restrictions, social distancing or hygiene measures present at all ages and across multiple types of play including outdoor play (e.g. ‘corona chasing’), construction play (e.g. building LEGO hospital wards) and pretend play (e.g. playing Doctors and Nurses). For example, in relation to pretend play, one parent of a seven-year-old girl stated that ‘she created a shop and used chalk to draw lines for social distancing and hand sanitizer at her shop stall’, while another parent of a seven-year-old noted that their child was ‘playing dead, playing doctors, pretend washing hands, pretend teach enforcing social distancing’. Regarding construction play, a parent of a five-year-old said, ‘She made bunk beds for Lego people that were sick & placed them far away from one another & only one person allowed in the bunk to social distance’, while a parent of a nine-year-old said their child ‘made a hospital with patients, ventilator and test centre with Lego’.

In addition to asking parents if their child had included information about the virus or restrictions in their play, parents were also specifically asked if they were aware of their child or other children playing a version of chasing related to the virus. Approximately eight percent of parents answered yes (39 responses out of 506), with over half of the responses indicating that it took place in their child’s school before closure (twenty-two of the thirty-nine responses, or fifty-six percent of responses about corona tag). All schools in Ireland closed on 13 March 2020 and did not reopen until September 2020. Those that described Covid-19 tag in another setting mainly mentioned that their child played it at home with a sibling. One parent also described the following:

My brother in Dublin has watched children playing ‘Corona’, which involves the person being ‘on’ calling ‘corona’ and the others have to get up on something as ‘quarantine’ as quickly as possible. There were other calls, hand washing, and points of some sort involved.

Other parents’ descriptions of the game were similar, with the person who was ‘on’ having ‘Covid’ and the children who were caught ‘catching Covid’. A parent of a seven-year-old described a ‘chase game with person on having germs!’, while another parent of a seven-year-old said, ‘He created a game of tig called coronavirus. He was trying to catch his sister pretending he had the virus and saying she’d catch it from him if he caught her’. The notion of Covid being deadly also featured in some of the games, with a parent of a nine-year-old mentioning ‘Tag, where child caught was said to die as they had the coronavirus’. A parent of a four-year-old noted that her daughter was ‘recently playing ghost tag with neighbour’s child’.

Implications of the Findings of the PLEY Covid-19 Survey

The findings of the Play and Learning in the Early Years Covid-19 survey provide important insights into children’s play at home in Ireland during the early stages of the Covid-19 pandemic. Given the timeframe of survey distribution, these findings provide valuable information regarding this unprecedented time for families in their home environments. The findings also highlight the value parents place on children’s play and the resources available to Irish children in the home play environment during the first lockdown of 2020.

While children and their parents globally have suffered many negative effects as a consequence of the pandemic and the resulting restrictions, the findings of the current study suggest that most children spent a considerable amount of time engaged in various types of play during lockdown. A wealth of research supports the developmental benefits of play (Kane 2016: 290, Schmitt et al. 2018: 181), as well as the therapeutic benefits of play in times of crisis (Chatterjee 2018: 119). Therefore, it is positive to note that for many children in Ireland the pandemic did not reduce the amount of time spent in various types of play.

As has been reported in other countries (e.g. Bergmann et al. 2022: 4; Moore et al. 2021: 6), the current findings indicate many children also spent a considerable time on screens during lockdown, with over seventy-five percent of children spending over an hour a day on screens. However, it is important to note that the findings reported above suggest that time on screens did not displace time for other types of play for children in Ireland, such as playing outdoors. Drawing on data from the same sample, Egan and Beatty (2021: 6) previously noted that most parents reported that their child was spending less time on schoolwork than before the pandemic. Therefore, the time for most children afforded to screen use may have been at the expense of time spent on schoolwork, rather than time spent on playful activities, as time spent playing with toys and games and playing outdoors was also high. The majority of children spent at least an hour a day on these activities.

However, that is not to say that the time spent on screens or on other types of play was not educational or beneficial in other developmental ways. For example, Egan and Beatty (2021: 7) reported that more than half of school-age children in the same sample used screens for schoolwork, to play educational games or watch educational television and videos on at least a weekly basis, with up to a quarter of participants engaged in some of these activities every day. Other research also highlights the benefits of screen use for maintaining social connections between children and their friends, and also their early years settings and schools (Bigras et al. 2021: 784), given the restrictions in place during 2020. Many researchers stress the need for a broader perspective to recognize both the positive and negative impacts of technology for children (e.g. Barron et al. 2021: 268; Beatty and Egan 2020: 26) and to consider the importance of play in digital spaces (Cowan 2020: 3; Colvert 2021: 7).

While there are some similarities between the findings of the current study and international findings (e.g. Moore et al. 2021: 4), there are also differences. For example, unlike research from Canada (Moore et al. 2021: 6), which showed a decrease in outdoor play in children aged from five to seventeen years, and research from China (Xiang, Zhang, and Kuwahara 2020: 531) that showed a decrease in physical activity in children aged from six to seventeen years, the findings from the current study suggest children in Ireland, aged from one to ten years, had high levels of outdoor play during lockdown. The World Health Organization recommends that children should engage in at least sixty minutes of physical activity per day (Bull et al. 2020: 1455), and the current study shows that during the first two months of lockdown in Ireland, eighty-eight percent of children engaged in this amount of outdoor play on a weekday, with ninety-five percent at the weekend. Factors that may have facilitated this increase in outdoor play relate to both the increased time at home, as well as the exceptionally sunny and warm weather Ireland experienced during this time in 2020. Additionally, children in Ireland have almost universal access to private outdoor space as the majority of housing stock in the country consists of houses with private gardens.

The changes in the amount of time spent in outdoor play are also evident when considered in light of data gathered in 2019, also using the Play and Learning in the Early Years Survey (Egan, Hoyne, and Beatty 2021: 224). These data were gathered between June and October 2019 and the findings showed that on a weekday, twenty-six percent of children spent less than an hour in outdoor play, with seventeen percent spending this amount of time on a weekend. In contrast, during lockdown these figures were twelve percent and five percent for a weekday and weekend respectively. Similarly, in 2019, thirty-seven percent spent over two hours in outdoor play on a weekday, whereas during lockdown in 2020 this figure was fifty-three percent. It seems that the amount of time spent in outdoor play was higher in 2020 than in 2019, particularly on a weekday.

It is evident also from the findings that most parents valued playing with their child, with nearly all parents indicating that they had a lot of fun when they played with their child and that it was important for them to do so. Parents also clearly valued play for supporting their child’s development, with nearly all parents agreeing that it supported cognitive, socio-emotional, language and communication skills. These beliefs about the value of play for their child, and the benefit in terms of building a good relationship with their child, was also borne out through their behaviour in playing with their child and the play resources provided by the parent in the home. For example, over half of the parents played with toys and games with their child multiple days per week while a third played pretend or make-believe games with them multiple days per week.

Encouragingly, the majority of parents reported that their home was a rich play environment for their young child. Nearly all parents indicated there were plenty of play resources in the home such as toys, pictures, books, music and materials for creative play. Given the closure of schools, early years settings and public playgrounds, as well as the two-kilometre travel-from-home restriction, this is particularly heartening to note. The findings from the current study highlight the rich home play environments available to children during the lockdown, both in terms of physical play resources as well as the play interactions between parent and child. These interactions will have been particularly important given that children were restricted to the home and missed out on interactions and playing with friends and other peers in early years and school settings (Egan et al. 2021: 928).

The Importance of Contextual Factors for Young Children’s Play

These findings highlight the importance of considering many factors when examining play during the pandemic, such as play resources in the home, parental beliefs about play, parental engagement in play, child’s age, local conditions related to lockdown restrictions and also the extent of school and playground closures. Bronfenbrenner’s (1979: 3, 2005: 4) bioecological model can provide a useful framework in which to make sense of these findings and further international research (Egan and Pope 2022: 15). How children played and who they played with were impacted at different system levels, from the microsystem environment of the home, through to the wider macrosystem environment incorporating cultural factors and government restrictions.

For example, decisions made on a macrosystem level by the government, such as business and school closures, had direct impacts on children and families at a microsystem level in the home. Barron et al. (2021: 375) reported that there was a high percentage of parental presence in the home during the Covid-19 lockdown (75.2%) but that this figure varied markedly across the four countries in their cross-cultural comparison. Ireland had the highest percentage of parents at home (86.9%) with rates considerably lower in the UK (69.2%), Italy (52.6%), and the United States (52.9%). They found that parents being present in the home was associated with higher rates of indoor play activities and cooperative play with parents across multiple activities, such as for playing board games, playing with toys, reading and doing arts and crafts. In previous studies, lack of time has been identified as a factor affecting how parents play with their children (Shah, Gustafson, and Atkins 2019: 606) combined with family structure (Fallesen and Gähler 2020: 361). Cultural factors in Ireland, such as a high level of access to private outdoor space (a garden), also influenced how children played in the microsystem of the home play environment with high levels of outdoor play present.

The high levels of play seen in this study are encouraging both from a developmental perspective as well as a potentially therapeutic perspective (e.g. Chatterjee 2018: 119). Approximately a third of parents in the PLEY Covid-19 study reported that their child had brought information about the virus or restrictions into their play, highlighting their awareness of the situation. This was apparent across multiple types of play (e.g. outdoor, pretend play, play with objects, etc.) and across multiple ages in early childhood. It was evident that children actively reproduce and reinvent societal information rather than passively internalizing what is happening around them. Similarly, Barron et al. (2021: 372) gathered data from parents and children, including photo images of play. They suggest that indoor play in the home environment, including using technology, may have helped as a coping mechanism and to build resilience.

While many of the findings regarding the time spent in play in this study are positive, with many children spending a lot of time playing, this was not the case for all children. For example, a number of children never or hardly ever engaged in some of the different types of play activities, such as playing with puzzles and jigsaws or with blocks and building materials, as Figure 12.2 illustrates. Additionally, across the various types of play, the findings suggest that a minority of parents never or hardly ever play with their child, at least in some of the activities measured in this survey. As might be expected, the findings highlight differences in family experiences during the pandemic with multiple positive and negative effects potentially being experienced by any one family. When interpreting the findings, it is therefore important that the limitations of the study are borne in mind.

For example, the sample has a high proportion of highly educated families who volunteered to participate in the study. While Ireland has one of the highest rates of adults with third-level education in Europe (Wilson 2021), future research should aim to include a more diverse sample of families from other educational and socioeconomic backgrounds. The recruitment method of parents through online means permitted all families to participate in the research and the links to the survey were widely shared by a variety of organizations and individuals. Given that the country was in lockdown at the time, with a two-kilometre limit of movements from home imposed on citizens, it was not possible to contact a diversity of families directly to invite them to participate. Therefore, access to a computer, smartphone or the internet, along with the time needed to participate, may have acted as a barrier to some parents in participating. Future research should consider in-person methods when recruiting for other studies on this topic.

It is also important that children with a range of intellectual and cognitive abilities are included in future research. Neurodiverse children may engage in different types of play in different ways (although it is important to recognize the individual nature of each child within their ecological systems rather than make generalizations). Children with additional learning needs, chronic illness or mobility considerations may play in certain ways specific to them which may also be shaped by their environment and the interactions they have, both directly and indirectly.

It is also imperative that future research involves young children directly to ascertain their views on the impact on their play and activities, in addition to the evidence provided through parental reports. While parental reports are useful, and were the most feasible measure during this initial lockdown period for children in this young age group, investigating young children’s views directly is also important. On a positive note, the data was collected directly during this unprecedented time rather than retrospectively, and therefore the risk of parental recall bias was minimized as completing the questionnaire during this timeframe did not require reflection or recall and was entirely anonymous.

Conclusion

The findings reported in this chapter represent the play experiences of families living in Ireland during this unprecedented time in their lives, the first Covid-19 lockdown in 2020. The literature highlights the important role of play for children in terms of coping with adversity and building resilience. It is therefore heartening to see that overall, many of the findings with regards to play were positive. Young children in Ireland spent a considerable amount of time in multiple types of play, in rich home play environments with parents who valued and facilitated their play both in terms of the physical resources they provided and the social support they engaged in while playing with their child. It is apparent based on the international research emerging that similar experiences were observed globally. However, it must be noted that there are also differences at the country as well as family level. Despite the child’s right to play, not every child had the resources available, environments conducive to play, siblings, peers or supportive adults with whom to play. Interpreting these results and other international research through a bioecological lens offers a good approach to make sense of and learn from these findings so that appropriate supports for families can be put in place, whatever their circumstances and wherever they live.

Works Cited

Almeida, Vandaet al. 2021. ‘The Impact of COVID-19 on Households’ Income in the EU’, Journal of Economic Inequality, 19: 413-31, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10888-021-09485-8

Barron, Carol, et al. 2021. ‘Indoor Play during a Global Pandemic: Commonalities and Diversities during a Unique Snapshot in Time’, International Journal of Play, 10: 365-86, https://doi.org/10.1080/21594937.2021.2005396

Beatty, Chloé, and Suzanne M. Egan. 2020. ‘Screen Time in Early Childhood: A Review of Prevalence, Evidence and Guidelines’, An Leanbh Óg, 13: 17-31

Bergmann, Christina, et al. 2022. ‘Young Children’s Screen Time during the First COVID-19 Lockdown in 12 Countries’, Scientific Reports, 12: 1-15, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-05840-5

Bigras, Nathalie, et al. 2021. ‘Early Childhood Educators’ Perceptions of their Emotional State, Relationships with Parents, Challenges, and Opportunities during the Early Stage of the Pandemic’, Early Childhood Education Journal, 49: 775-87, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-021-01224-y

Bronfenbrenner, Urie. 1979. The Ecology of Human Development: Experiments by Nature and Design (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press)

—— (ed.). 2005. Making Human Beings Human: Bioecological Perspectives on Human Development (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage)

Bull, Fiona C., et al. 2020. ‘World Health Organization 2020 Guidelines on Physical Activity and Sedentary Behaviour’, British Journal of Sports Medicine, 54: 1451-462, http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2020-102955

Chatterjee, Sudeshna. 2018. ‘Children’s Coping, Adaptation and Resilience through Play in Situations of Crisis‘, Children, Youth and Environments, 28: 119–45, https://doi.org/10.7721/chilyoutenvi.28.2.0119

Colvert, Angela. 2021. The Kaleidoscope of Play in a Digital World: A Literature Review (London: Digital Futures Commission 5Rights Foundation), https://digitalfuturescommission.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/DFC-Digital-Play-Literature-Review.pdf

Cowan, Kate. 2020. A Panorama of Play: A Literature Review (London: Digital Futures Commission 5Rights Foundation) https://digitalfuturescommission.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/A-Panorama-of-Play-A-Literature-Review.pdf

Egan, Suzanne M., and Chloé Beatty, 2021. ‘To School through the Screens: The Use of Screen Devices to Support Young Children’s Education and Learning during the COVID-19 Pandemic’, Irish Educational Studies, 40: 275-83, https://doi.org/10.1080/03323315.2021.1932551

Egan, Suzanne M., Clara Hoyne, and Chloé Beatty. 2021. ‘The Home Play Environment: The Play and Learning in Early Years (PLEY) Study’, in Perspectives on Childhood, ed. by Aisling Leavy and Margaret Nohilly (Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholar Publishing)

Egan, Suzanne M., and Jennifer Pope. 2022. ‘A Bioecological Systems Approach to Understanding the Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic: Implications for the Education and Care of Young Children’, in The COVID-19 Pandemic: Effects on Early Childhood Education and Care: International Perspectives, Challenges, and Responses, ed. by Jyotsna Pattnaik and Mary Renck Jalongo, Educating the Young Child, 18 (Cham, Switzerland: Springer), pp. 15-31, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-96977-6_2

Egan, Suzanne M., et al. 2021. ‘Missing Early Education and Care during the Pandemic: The Socio-emotional Impact of the COVID-19 Crisis on Young Children’, Early Childhood Education Journal, 49: 925-34, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-021-01193-2

Fallesen, Peter, and Michael Gähler. 2020. ‘Family Type and Parents’ Time with Children: Longitudinal Evidence for Denmark’, Acta Sociologica, 63: 361-80, https://doi.org/10.1177/0001699319868522

Fisher, Kelly R., et al. 2008. ‘Conceptual Split? Parents’ and Experts’ Perceptions of Play in the 21st Century’, Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 29: 305-16, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appdev.2008.04.006

Fogle, Livy M., and Julia L. Mendez. 2006. ‘Assessing the Play Beliefs of African American Mothers with Preschool Children’, Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 21: 507-18, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2006.08.002

Fore, Henrietta H., and Zeinab Hijazi. 2020. ‘COVID-19 Is Hurting Children’s Mental Health: Here Are 3 Ways We Can Help’, World Economic Forum, 1 May, https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2020/05/covid-19-is-hurting-childrens-mental-health/

Ginsburg, Kenneth R. 2007. ‘The Importance of Play in Promoting Healthy Child Development and Maintaining Strong Parent-Child Bonds’, Pediatrics, 119: 182-91, https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2006-2697

Goodman, Robert. 1997. ‘The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire: A Research Note’, Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 38: 581-86

Hayes, Nóirín, Leah O’Toole, and Ann Marie Halpenny. 2017. Introducing Bronfenbrenner: A Guide for Practitioners and Students in Early Years Education (New York: Routledge)

Hirsh-Pasek Kathy, Dorothy G. Singer, and Roberta M. Golinkoff. 2006. Play = Learning: How Play Motivates and Enhances Children’s Cognitive and Social-emotional Growth (Oxford: Oxford University Press)

Howard, Justine, and Karen McInnes. 2013. ‘The Impact of Children’s Perception of an Activity as Play Rather Than Not Play on Emotional Well-being’, Child: Care, Health & Development, 39: 737-42, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2214.2012.01405.x

Kane, Nazneen. 2016. ‘The Play‐Learning Binary: US Parents’ Perceptions on Preschool Play in a Neoliberal Age’, Children & Society, 30: 290-301, https://doi.org/10.1111/chso.12140

López-Aymes, Gabriela, et al. 2021. ‘A Mixed Methods Research Study of Parental Perception of Physical Activity and Quality of Life of Children under Home Lockdown in the COVID-19 Pandemic’, Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 649481 https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.649481

McCrory, Cathal, et al. 2013. Growing Up in Ireland: Design, Instrumentation and Procedures for the Infant Cohort at Wave Two (3 Years), Technical Report, 3 (Dublin: Department of Children and Youth Affairs), https://www.growingup.ie/pubs/BKMNEXT253.pdf

Moore, Sarah A., et al. 2020. ‘Impact of the COVID-19 Virus Outbreak on Movement and Play Behaviours of Canadian Children and Youth: A National Survey’, International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 17: 1-11, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-020-00987-8

Parten, Mildred B. 1932. ‘Social Participation among Pre-school Children’, Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 27: 243-69, https://doi.org/10.1037/h0074524

Rothbart, Mary K., et al. 2001. ‘Investigations of Temperament at Three to Seven Years: The Children’s Behavior Questionnaire’, Child Development, 72: 1394-408, https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8624.00355

RTÉ [Raidió Teilifis Éireann] News. 2020. ‘Timeline: Six Months of Covid-19’, 1 July, https://www.rte.ie/news/newslens/2020/0701/1150824-coronavirus/

Schmitt, Sara A., et al. 2018. ‘Using Block Play to Enhance Preschool Children’s Mathematics and Executive Functioning: A Randomized Controlled Trial’, Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 44: 181-91, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2018.04.006

Shah, Reshma, Erika Gustafson, and Marc Atkins. 2019. ‘Parental Attitudes and Beliefs Surrounding Play among Predominantly Low-income Urban Families: A Qualitative Study’, Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics, 40: 606-12, https://doi.org/10.1097/DBP.0000000000000708

Shakel, Rita. 2015. ‘The Child’s Right to Play. Laying the Building Blocks for Optimal Health and Well-Being’, in Enhancing Children’s Rights. Connecting Research, Policy and Practice ed. by Anne B. Smith (London: Palgrave Macmillan), pp. 48-61

Thorell, Lisa B., et al. 2021. ‘Parental Experiences of Homeschooling during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Differences between Seven European Countries and between Children with and without Mental Health Conditions’, European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 1-13, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-020-01706-1

Thorn, William, and Stéphan Vincent-Lancrin. 2022. ‘Education in the Time of COVID-19 in France, Ireland, the United Kingdom and the United States: The Nature and Impact of Remote Learning’, Primary and Secondary Education During Covid-19: Disruptions to Educational Opportunity During a Pandemic, ed. by Fenando M. Reimers (Cham, Switzerland: Springer), pp. 383-420, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-81500-4_15

UNICEF. 1989. Convention on the Rights of the Child, https://www.unicef.org/child-rights-convention

Whitebread, David, et al. 2012. The Importance of Play (Brussels: Toy Industries of Europe)

Williams, James, et al. 2019. Growing Up in Ireland: Design, Instrumentation and Procedures for Cohort ’08 at Wave Three (5 Years), Technical Series, 2019–2 (Dublin: Department of Children and Youth Affairs), https://www.growingup.ie/pubs/20190404-Cohort-08-at-5years-design-instrumentation-and-procedures.pdf

Wilson, Jade. 2021. ‘Ireland Has Higher Rates of Third Level Education than EU Average, Data Shows’, Irish Times, 29 November, https://www.irishtimes.com/news/education/ireland-has-higher-rates-of-third-level-education-than-eu-average-data-shows-1.4741763

Xiang, Mi, Zhiruo Zhang, and Keisuke Kuwahara. 2020. ‘Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on Children and Adolescents’ Lifestyle Behavior Larger than Expected’, Progress in Cardiovascular Diseases, 63(4): 531-32, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pcad.2020.04.013