14. The Observatory of Children’s Play Experiences during Covid-19:A Photo Essay1

© 2023, John Potter and Michelle Cannon, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0326.14

Introduction

The Play Observatory was a study of children’s play experiences during the pandemic, conducted almost wholly online over a seventeen-month period between October 2020 and March 2022. It was funded in the UK by the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC) as part of the UK Research Institute (UKRI) Rapid Response to COVID-19, and was a collaboration between researchers at the IOE, University College London’s Faculty of Education and Society, the School of Education at the University of Sheffield, and the University College London Centre for Advanced Spatial Analysis (UCL CASA). A key aim of the project was to collect, analyze and preserve for future generations material from children and adults in the form of text, images, moving images and more which represented their play experiences during such a challenging and difficult time, but which also demonstrated the function of play in their lives in terms of well-being and resourcefulness.

The online survey and collection tool, through which most of the contributions to the project were uploaded, was carefully designed to be a child- and carer-friendly submission area by the University of Sheffield team members, Yinka Olusoga, Julia Bishop and Catherine Bannister, with Valerio Signorelli from UCL CASA. This was linked from the main project website and was a welcoming and informative space. Contributors encountered detailed information about the project’s ethical stance, the importance of informed consent and, where requested, the preservation of anonymity. It also contained clear guidance through the submission process and prompts for memories of play in pandemic times.

For this chapter, we have selected examples of twelve image submissions to the Play Observatory to take the form of a ‘photo essay’. The selection process involves us in processes which are akin to academic thematic analysis but arguably closer to personal curation, allowing space for interpretation and representing an invitation for readers to do work on the images, to see connections and traces through them, rather than fixing precise meanings. The act of curating these has, of course, been conducted simultaneously with the more systematic and research-bound elements in the study whilst at the same time admitting a space for playful interpretation, in the spirit of provisionality and ‘possibility thinking’ which are themselves characteristics of ‘play’.

Readers may have encountered some of what follows already in an online exhibition which we have taken part in with the Young V&A (Young V&A, Episod Studio, and Play Observatory 2022). However, we have resisted the categories employed in that larger selection, preferring instead to leave this open to the reader. We have also limited our captions to initial framing comments, these being the signposts we were initially guided by when we first saw the submissions. The majority of the images we have chosen come from UK sources but three of the twelve are from outside the UK. This is slightly higher than the overall proportion of non-UK vs UK submissions to the observatory as a whole, which is closer to fifteen percent.

We hope that readers will enjoy ‘reading’ these images in the same way we first did, with curiosity and without too much pre-judgement, but inevitably informed by their own experience of the pandemic, its lockdowns and restrictions. We offer these images to this volume as important visual reminders of our collective pandemic experience and to express our gratitude to the contributors for the privilege of bearing witness to intimate and familial play experiences at such a sensitive time. By bringing their own memories and thoughts to the ‘pact of interpretation’ (Bhabha 1994), our contributors’ mediated voices are heard and valued in this essay, enabling rich, multiple and enduring readings of play in the pandemic.

A Note on Photo Essays

Before getting to the images, and because this will necessarily be different in nature to most of the other chapters, it is perhaps worth considering the purposes of a photo essay and maybe even to begin by asking what a photo essay is, or can be, in this context. Marín and Roldán (2010: 10-11), for example, distinguish between two different kinds of ‘photo series’ when defining a photo essay for educational research purposes. They argue that the first of these represents an organization of images into a congruent sequence, representing multiple, transforming versions of the same subjects or motifs. They present the second archetype as a set of congruent, sampled images ‘in which the same […] phenomenon is presented through a number of single cases’. Our version of the photo essay in this chapter is closer to the first idea of a ‘series’ but adds some of the features of photo essays used for a specific, ideological intervention around, for example, race, gender or critical pedagogy (Grimwood, Arthurs and Vogel 2015; Sensoy 2011). Our stance is one of underlining the importance of play for children and young people and its potential benefits in times of crisis, whilst at the same time refusing a simplistic equation of play and positive experience.

One of our stated aims in the project has been to find ways to represent the experience of lockdown for children which refuses some of the simple binaries, such as ‘screens are bad, play offscreen is good’, or the prevailing discourse of ‘learning loss’ as the only consequence that mattered for children in lockdown during the pandemic. Thus, this is not to pretend that the photographs have set out without any organizing principle. We have in fact sought to represent our belief that play, of all kinds, is central to children’s lives and that we need to think how best to capture the experience of children and young people at this moment in history and how to archive it for future generations to explore.

Much of the literature of the photo essay assumes a sole author who takes the images and arranges them in order to carry out these functions. Our own role is different because we are not presenting material which we have ourselves created and uploaded (although for full disclosure, we should acknowledge that two of the images were submitted by team members).

Rather than acting as photo essay authors, and presenting our own images, we are curators of other people’s contributions, of other people’s images. As researchers of media, we may also have in mind other photo essays in which this is employed as a strategy, such as that which opens Lev Manovich’s Language of New Media (2001), in which a series of black and white images set out a view of analogue versus digital media. These do more than simply establish a context. They invite interpretation from those who are already perhaps thinking about the worldview of Manovich; they understand that the work will exist somewhere between photography, technology, platform studies and cultural studies. Readers of this book will range from those interested in play theory, health and well-being, archival and folklore studies. All of these interests will sit within the context of a global pandemic and what it has meant for play, and these will also produce particular kinds of interpretations and generate relevant questions which could be asked of the images.

To return to Marín and Roldán (2010), we have an intention to represent the project in some way, to curate a small, congruent photo series which demonstrates something of the life of the project but also of what John Law (2004) calls the ‘mess’ of human experience. We see here examples of the ‘mess’ and the variety of organization of people, spaces and things which came into the Play Observatory. In being honest about our curatorial activity, we must declare that these examples are partial, restricted and the tip of a metaphorical iceberg of emotion and affect in children’s play, and adult responses to it, during the pandemic. There is much more to be said about this, and the team is preparing dissemination in many different forms to accompany what has already been exhibited, said and written about this project online and in print (Cowan et al. 2021).

In what follows we have included some of the text which accompanied the deposit of the image, mostly from the adult contributor, except where indicated, along with a small amount of further contextual detail on the games and on-screen environments shown in the images, where applicable.

We would like to note, however, that the images refuse absolute fixity of interpretation. They are moments in time, in which the subjects of the image are often lost in the experiential flow of play. They are, of course, only a subset of some of the forms of play we have seen in the submissions which are themselves a subset of the wider human experience of the pandemic. We are under no illusion that these contributions represent people who answered the call and who had the time, ability and resources to upload these images. We are very grateful that they did so, mostly in the UK but also in Europe and, in one case, far beyond. We know that there were others we were not able to reach during the relatively short time we were collecting instances of pandemic play. Our hope is that these images will reach out beyond the Play Observatory and inspire others to seek out images and to think about submitting them when next we open the doors of the observatory. We certainly hope to be able to do that again, one day, and to extend our reach to communities whose voices are often absent in research.

For now, we invite you, the reader, to look through the images and seek connections to your own experiences, or those of friends and family. How would you categorize them and analyze them? What can you say about these human experiences and the meanings that are being made within the images which have been submitted?

Figure 14.1 ‘Child and chalked rainbow’, Sheffield, UK, 2020-21

Play Observatory PL38A1/S001/p1, https://doi.org/10.15131/shef.data.21198142

CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

Observed in Meersbrook Park—big murals on the floor of the car park by the hall. Colourful pictures, messages of positivity and specially constructed trails. (Parent)

Additional note: Rainbows in a variety of media appeared during the pandemic in many countries, including the UK, and were used as both private and public displays of hope. The origin is unclear, but they had wide appeal and as early as April 2020 an article on the BBC Global website reported their deep connection to wider cultures as symbols of ‘thank you, hope and solidarity’ (Vince 2020). They appeared in many sizes and different locations. Here, the child is right at the centre of a large rainbow made in a car park.

Figure 14.2 ‘Child doing Cosmic Yoga’, Kusterdingen, Germany, 2020

Play Observatory PL65A1/S007/p1, https://doi.org/10.15131/shef.data.21198142

CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

Cosmic kids yoga[.] My 4-year-old got really into doing cosmic kids yoga on YouTube. At the peak of his interest he was doing it everyday! Sometimes I did it with him, sometimes he did it alone. Occasionally he did it along with a friend online—we set up a zoom meeting, one child shared his screen, and they did a yoga session together.’ (Parent)

Additional note: With the loss of amenity and access to outdoor spaces in the strictest of lockdowns, exercise at home became a feature of daily life in many locations. In this image there is a playful interaction between a child and a YouTube yoga channel for children (Cosmic Kids Yoga n.d.) with the child attempting to mirror the pose on-screen. UNICEF reported positively on the uses of screens which were emerging during lockdown, including for playful exercise (Winther 2020).

Figure 14.3 ‘Masked and socially distanced small toys’, Singapore, 2020-21Play

Observatory PL175A1/S001/p2, https://doi.org/10.15131/shef.data.21198142

CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

My daughter likes to play pretend with her collection of TY soft toys. During the pandemic, [this] pretend play takes on medical/pandemic related themes. For example, the soft toys will be wearing [expired] masks we have at home and attending school—much like her own experience of having to wear masks at school. She has mentioned that she dislikes doing so and including this in her pretend play could be a way to make sense of the situation. (Parent)

Figure 14.4 ‘Joint birthday party in Minecraft’, Sheffield, UK, May 2021

Play Observatory PL170A1/S007/p2, https://doi.org/10.15131/shef.data.21198142

CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

Play in Minecraft ‘[…] organised by my eldest son […] to mark his 15th birthday in 2021 and his younger brother’s 10th birthday. He said: ‘On May 11th we held a birthday festival-type celebration for me and [my brother] near Breadburg (Bread Empire capital). First we had a disco and ate cake and cookies. Then we played some minigames (parkour, trampoline, and one [a friend] designed where you have to complete an obstacle course and die at the end) […]’ (Parent and child)

Additional note: Microsoft, which owns Minecraft, provided its educational worlds for free use during the pandemic to support parents and children. Minecraft has previously been written about by researchers as supportive of a broad range of social and cultural developments as well as of media literacy education (see, for example, Dezuanni 2018).

Figure 14.5 ‘Homemade den showing exterior and interior with child’, Nicosia, Cyprus, April 2020

Play Observatory PL72A1/S003/p1, https://doi.org/10.15131/shef.data.21198142

CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

We built this tent house on the balcony once and he asked to do it again a lot of times […] My son seemed to have strong intentions and determination on building it and choosing and putting stuff in it. It was nice and it engaged us for quite some time, though it made me feel a bit sad. I felt like he needed ‘some other place’ to be when we couldn’t go anywhere. (Parent)

Additional note: The two images were uploaded to the Play Observatory as a single submission to show the exterior and interior of the den. Children’s uses of dens and safe spaces in which to play and build their own worlds, both indoors and outdoors, has been written about and researched extensively, including by children themselves (see, for example, Burke 2007; Sobel 2001). With so much strangeness and uncertainty during lockdown, these forms of den building during the pandemic were, arguably, attempts by children to take control of their immediate environment and create a safe place in which to be.

Figure 14.6 ‘Child drawing with chalk outside the house’, Leeds, UK, April 2020

Play Observatory PL34C1/S001/p1, https://doi.org/10.15131/shef.data.21198142

CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

I did chalk drawings on the drive in front of my house. I was playing by myself, and my mum was sitting on a chair by the front door, doing her work on her iPad. I didn’t really like people and because of COVID I didn’t want people to come near the house and act like COVID doesn’t exist. So, I did chalk drawings of things like a ghost, a bottle of poison, a skull and crossbones and I wrote Keep Out. Later my sister came out and we drew a creeper from Minecraft as well. I called this pandemic panic drawing. (Child)

Figure 14.7 ‘Children watching cardboard cinema screen outside’, Sheffield, UK, March 2021

Play Observatory PL79A1/S001/p1, https://doi.org/10.15131/shef.data.21198142

CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

‘Outdoor cinema’. My nieces are aged 3 and 4 1/2 and like most children today they love screen time. On a sunny day (and when their mum was trying to clean the house) she told them to play outside instead of on their iPads in the house. Before they could throw a tantrum, my sister helped make some cardboard boxes into a tv screen. It was the girls’ idea to make chairs to sit and watch the frozen ‘frozen’ on the screen.’ (Aunt)

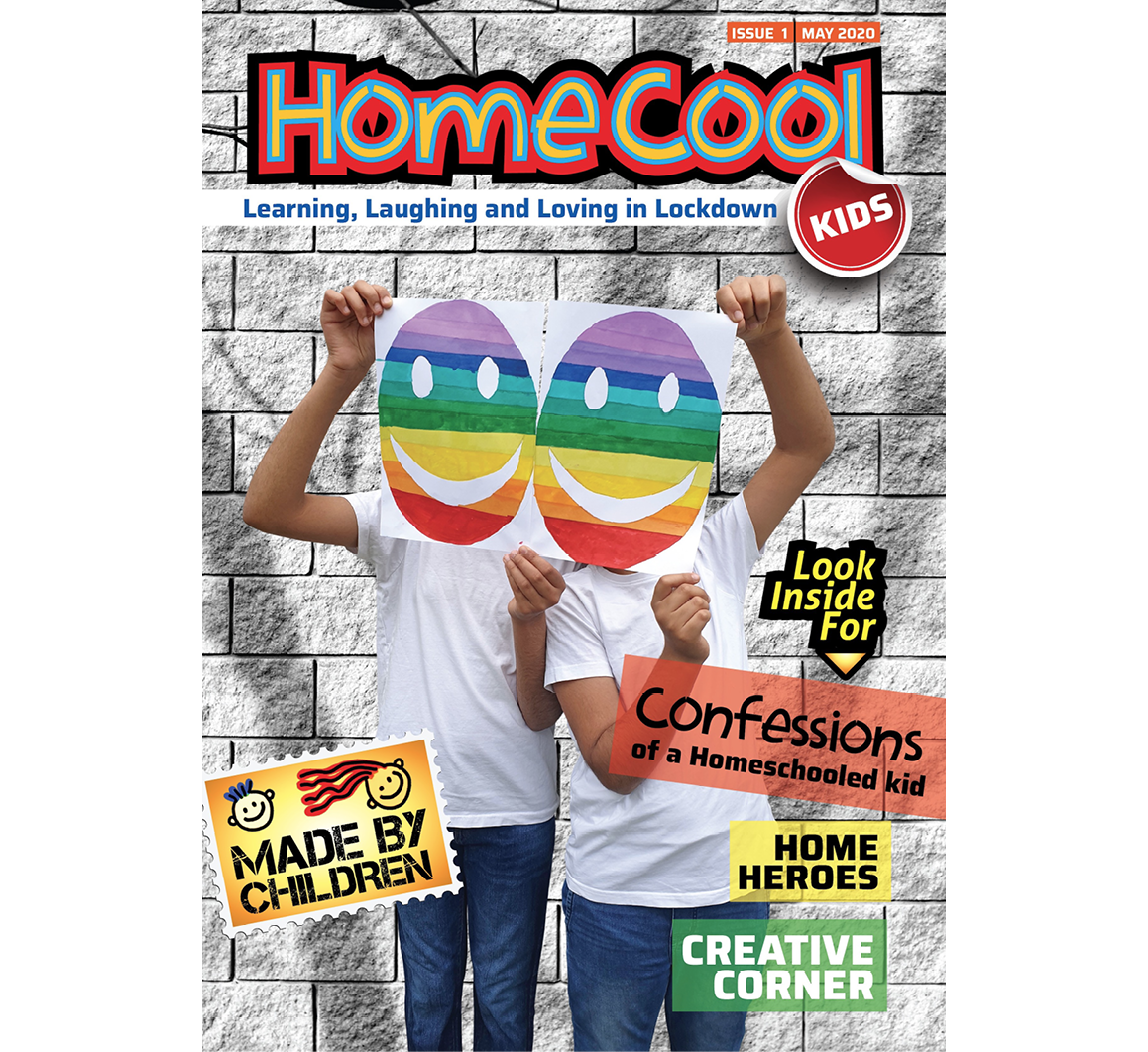

Figure 14.8 ‘HomeCool Kids magazine cover’ Birmingham, UK, May 2020

Play Observatory PL158A1/S001/p8

Image © HomeCool Kids, 2023, all rights reserved

Setting up HomeCool Kids gave the children an opportunity to interact with their friends and the magazine has actually been the highlight of our other pandemic experiences. For us the Pandemic has actually been enjoyable as we have spent more time together. However, we have also missed out on seeing our extended family back in India. Our summer holidays have always been spent in India with family and that the children definitely miss—not being able to visit their grandparents but also the play and socialising aspect of the community. In India, X1 and X2 would spend most of their time outdoors playing with their cousins and other children from the neighbourhood. That is something that they definitely miss. (Parent)

Figure 14.9 ‘Intergenerational LEGO play and sorting’, Nottingham, UK, 2020-21

Play Observatory PL78C1/S005/p2, https://doi.org/10.15131/shef.data.21198142

CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

Not exactly playing—but we took the time to sort out all of my Lego and rebuild everything!

Took over the front room! Mum and dad helped.

It was fun to start with, then got boring, then was go[o]d once we’d rebuilt everything! (Child)

Additional note: A recurring theme for us in the Play Observatory has been the changing nature of play within families, particularly in situations where siblings separated in age by more than a few years were forced to play with each other, when they did not normally. The same situation occurred where adults who had one child joined in more with activities which might previously have been undertaken with friends in the peer group. The LEGO construction activity shown in Figure 14.9 clearly levelled the playing field between parents and child and was quite complex, with lots of sorting, shared endeavour and concentration in evidence. The accompanying comment, in the child’s own words, is particularly interesting for what it says about collaborations and shared purpose in play.

Figure 14.10 ‘Children playing in a stream with their dog’, North Anston, UK, March-June 2020

Play Observatory PL80A1/S002/p1, https://doi.org/10.15131/shef.data.21198142

CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

We live near a common access space called the Anston Stones, which comprises open grassland, woods and a stream that runs the length of [a] low valley this long series of fields and woods follow. Mostly it would be me taking the children out with the dog […] The walks grew in length as we got to know more routes in the Stones and as the weather got warmer and we learned to take things like wellies to paddle in the stream. E was 2 at this time, so the off-roader buggy meant we could carry equipment and snacks underneath the seat and extend the range of activities we did beyond just walking. We also played ‘pooh sticks’ at the two bridges across the stream and threw sticks in for the dog to get. [It was] relaxing and fun, especially for the older child, for whom it was a break from the schoolwork. I think we also felt joy at the freedom of being outside our house and garden, as there were no other places the children could go in that time period. (Parent)

Figure 14.11 ‘Child pointing at spider in a plastic tank’, Sheffield, UK, 2020-21

Play Observatory PL172C1/S001/p2, https://doi.org/10.15131/shef.data.21198142

CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

I used to go for walks in lockdown[.] I used to do my homeschool[.] My Grampa and gramma did storytime on zoom[.] We went on nature walks and did tree rubbings[.] We set up a spider tank and caught a spider from the garden[.]

[On lockdown] I felt like [it] could have been easier but also could have been harder. I felt like I were alone, lonely[.] I did like some bits, like the fun bits, but I wanted to see my friends and play. I feel like this [is] what must [most?] people would say as well (Child)

Figure 14.12 ‘Children in a tyre’, Ipswich, UK, June 2020

Play Observatory PL48A1/S009/p1, https://doi.org/10.15131/shef.data.21198142

CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

Playing with a tractor tyre, jumping, hiding[.] Sisters and brother N, i and E on a daily walk […] early evening around our local rugby field. The players had left out tractor tyres to train with and the children enjoyed climbing on equipment on them, jumping across the gap and hiding inside. [Their mood was] relaxed, happy, inventive. (Parent)

Additional note: This image typifies the results of exploratory walks close to home and the use of found materials in the environment in which to play, which chimes both with den building and thinking concerning outdoor play more generally (Whitebread et al. 2017). Its selection for inclusion by the parent also makes a statement about the relationships between the siblings, close in age and encircled within their own play space.

Final Note

This photo essay is a small, curated selection of twelve items from hundreds of images submitted to the Play Observatory. There has been some attempt, as you will probably have noticed, to be representative of some of the many different forms of play which have come into the survey. We have also tried to convey different emotions in the still images collected, as well as to show play by individual children, in family groups, and with and without adults. The hope is that seeing the images and reading them alongside the intertextual clues in the segments of chosen captions will pique interest and will drive readers to explore the project website more closely (https://play-observatory.com/), with its blogposts from the team, from children and from guests who have been undertaking similar work, in much the same way as you can when browsing this edited collection. It will also, perhaps, give you the opportunity to reflect on your own experiences of pandemic play and to share them with others.

Much of the public discourse has been focused on ‘learning loss’ as the key experience of the pandemic for children. Whilst the impact on schooling has been significant, the Play Observatory has attempted to shine a light instead on the impact on play as a key aspect of human behaviour during the pandemic, essential to our understanding of the world, of each other and how we can live together in times of crisis.

Works Cited

Bhabha, Homi K. 1994. The Location of Culture (London: Routledge)

Burke, Catherine. 2007. ‘Play in Focus: Children Researching their Own Spaces and Places for Play’, Children, Youth and Environments, 15: 27-53, https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.7721/chilyoutenvi.15.1.0027

Cosmic Kids Yoga. n.d. Yoga, Mindfulness, Relaxation…For Kids! https://www.youtube.com/c/CosmicKidsYoga

Cowan, Kate, et al. 2021. ‘Children’s Digital Play during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Insights from the Play Observatory’, Journal of e-Learning and Knowledge Society, 17.3: 8-17, https://doi.org/10.20368/1971-8829/1135590

Dezuanni, Michael. 2018. ‘Minecraft and Children’s Digital Making: Implications for Media Literacy Education’, Learning, Media and Technology, 43: 236-49, https://doi.org/10.1080/17439884.2018.1472607

Grimwood, Bryan S. R., Whitney Arthurs, and Tristin Vogel. 2015. ‘Photo Essays for Experiential Learning: Toward a Critical Pedagogy of Place in Tourism Education’, Journal of Teaching in Travel & Tourism, 15: 362-81, https://doi.org/10.1080/15313220.2015.1073574

Law, John. 2004. After Method: Mess in Social Science Research (London: Routledge)

Manovich, Lev. 2001. The Language of New Media (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press)

Manovich, Lev. 2017. Instagram and Contemporary Image, http://manovich.net/index.php/projects/instagram-and-contemporary-image

Marín, Ricardo, and Joaquin Roldán. 2010. ‘Photo Essays and Photographs in Visual Arts-based Educational Research’, International Journal of Education through Art, 6: 7-23, https://doi.org/10.1386/eta.6.1.7_1

Sensoy, Özlem. 2011. ‘Oppression: Seventh Graders’ Photo Essays on Racism, Classism, and Sexism’, International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 24: 323-42, https://doi.org/10.1080/09518398.2011.561817

Sobel, David. 2001. Children’s Special Places: Exploring the Role of Forts, Dens, and Bush Houses in Middle Childhood (Detroit: Wayne State University Press)

Vince, Gaia. 2020. Rainbows as Signs of Thank You, Hope and Solidarity (BBC Global),https://www.bbc.com/culture/article/20200409-rainbows-as-signs-of-thank-you-hope-and-solidarity

Whitebread, David, et al. 2017. The Role of Play in Children’s Development: A Review of the Evidence (research summary) (LEGO Foundation), https://cms.learningthroughplay.com/media/esriqz2x/role-of-play-in-childrens-development-review_web.pdf

Winther, Daniel K. 2020. ‘Rethinking Screen-time in the Time of COVID-19’, UNICEF, https://www.unicef.org/globalinsight/stories/rethinking-screen-time-time-covid-19

Young V&A, Episod Studio, and Play Observatory. 2022. Play in the Pandemic [online exhibition], https://playinthepandemic.play-observatory.com

1 With thanks and acknowledgements to the other members of the Play Observatory team: Catherine Bannister, Julia Bishop, Kate Cowan, Yinka Olusoga and Valerio Signorelli. We would like to thank all contributors to the Play Observatory for sending us their examples of play during Covid-19.