16. ‘We Stayed Home and Found New Ways to Play’:A Study of Playfulness, Creativity and Resilience in Australian Children during the Covid-19 Pandemic

© 2023, Judy McKinty et al., CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0326.16

Introduction

This chapter explores the way children in Australia responded to the Covid-19 pandemic through their play during lockdown in 2020. Descriptions of play activities were collected for the Pandemic Play Project (‘the project’), an independent study of Australian children’s play during the pandemic. The project was conducted and self-funded by Ruth Hazleton and Judy McKinty, independent play researchers based in Melbourne, Victoria. We had the support of a group of eminent Australian academics and researchers from three states,1 who have been collecting, studying and writing about folklore and children’s play over many decades (Pandemic Play Project 2020). Because of Covid-19 restrictions, the project was carried out almost entirely online, and under one of the longest and strictest lockdowns in the world (Fernando 2020; Mannix 2020).

The aim of the project was to find out:

- how children have taken the coronavirus into their play repertoire

- how they stayed playful at home during lockdown, and

- how the pandemic affected the way they play with their friends at school.

The project began because of our personal and professional interest, as folklorists, in children’s traditional games and the play culture of the schoolyard. We wanted to find out if the coronavirus had found its way into school playgrounds in the form of games, rhymes or other traces in the children’s play. However, during the course of our research we extended the scope to include younger children and a wider range of activities. This was necessary because, in 2020, children in Victoria spent more time with their families in lockdown than they did at school.

The main portal for the project was a Facebook page which connected to a website (https://pandemicplayproject.com) and email address. This allowed people to submit their contributions as various media: images, video and audio files, short text messages and longer emails. The written submissions were mostly from adults, with descriptions and lists of their children’s games and activities, sometimes with images, personal comments or observations. The audio and video submissions were mostly games, rhymes and songs in the children’s own voices.

The project was launched in June 2020, at a time when most countries, including Australia, had already experienced lockdowns at a local or national level (BBC News 2020). A devastating ‘second wave’ of the pandemic in July 2020 effectively isolated the state of Victoria from the rest of Australia, with borders closed and movement severely restricted in Melbourne, the capital city, where the project was based. While other children went back to school to play with their friends, children in Victoria were placed in lockdown for a further sixteen weeks (Boaz 2021). In a special report, released on World Mental Health Day 2021, Save the Children (2021b) analyzed the long-term effects of the Covid-19 lockdowns on children globally. The analysis revealed that ‘on average Australian children spent 60 days in lockdown’, although ‘the figure varies dramatically across states and territories. Children in Melbourne have spent 251 days in lockdown since the start of the pandemic’.

Victoria’s severe Covid-19 outbreak and extended restrictions forced the project online, which had advantages as well as constraints. With no geographical boundaries, submissions were received from every Australian state and territory except South Australia and the Northern Territory. Most of the information about play in lockdown came from families in Victoria, as the rest of the country had already moved on to a somewhat ‘Covid-normal’ life at that stage.

There were three key findings arising from our review of the submissions:

- the important role of adults in helping children stay playful during lockdown

- the creativity, imagination and resourcefulness of children in their play

- the importance of children’s own culture and play traditions in terms of expression and responses to Covid.

In this chapter we give examples of play in relation to our key findings, discuss the relationship between digital play and children’s own culture and play traditions, and present a case study of how playworkers at The Venny Inc. supervised adventure playground used a determinedly playful approach to support the well-being of local children living in high-rise public housing during the trauma of multiple lockdowns.

The descriptions of games and other play activities in this chapter, and quotes other than those directly referenced, come from submissions to the Pandemic Play Project2 and our own observations of children at play during lockdown. Contributors were personally contacted and written permission was obtained from informants and parents before public use of the material submitted to the project. Some of the information in this chapter has previously been published in the International Journal of Play, and has been reprinted with permission (McKinty and Hazleton 2022: 12-33).

Play in Times of Crisis

The role of play as a fundamental element in children’s lives has long been acknowledged in academic and clinical research, as Brown states: ‘Neuroscientists, developmental biologists, psychologists, social scientists, and researchers from every point of the scientific compass now know that play is a profound biological process’. He goes on to say that ‘Play is the vital essence of life. It is what makes life lovely’ (2010: 5, 12). Playing is how children form friendships, navigate social relationships and learn about their own culture through their games and play activities. Through play, children connect with each other and gain understanding of the world around them, a subtle process that takes time. Play Wales (2014: 2), one of the United Kingdom’s foremost advocates for children’s right to play, affirms the importance of play in this process:

Making sense of the world is an enormous task for young children. They are constantly at risk of being overwhelmed by events or feelings. By re-enacting and repeating events, and by playing out their own feelings and fantasies, children come to terms with them and achieve a sense of mastery.

In a crisis like the Covid-19 pandemic, when their world is changing rapidly, play can also help children to build emotional strength. It is ‘the foundation stone of resilience in children, no matter what life may throw at them’ (Shooter 2015: 4). To many Australian children, 2020 became ‘the year they closed the schools’. As SARS-CoV-2 infections spread, end-of-term holidays came early in some places, with car trips and plane flights banned, playgrounds out-of-bounds and ‘stay-at-home’ restrictions keeping families in their homes most of the time. Lockdowns forced families into prolonged close contact, and the only way to see friends was on-screen, using Zoom, Skype, FaceTime or other video conferencing programmes (McKinty 2020).

Children with access to digital technology could play with friends remotely. At its simplest, this meant sharing a Skype game of chess using two boards, one at each end; more complex engagement involved meeting a friend’s avatar in a Minecraft world, or one of many online multi-player games. The activity children were not able to do was the thing they missed most—to play freely with their friends, a yearning shared by children around the world and captured in reports, articles and children’s own descriptions of life during the pandemic (Henry Dodd 2020; Save the Children 2020; Stoecklin et al. 2021; Tucci, Mitchell, and Thomas 2020: 3, 12).

Three Key Findings

1. The Important Role of Adults in Helping Children Stay Playful during Lockdown

Coronavirus entered Australia in January 2020. During the pandemic, intermittent lockdowns were implemented as a way of reducing the spread of the virus. In addition to initial public health measures, such as hand hygiene and social distancing, lockdown restrictions included:

- ‘stay-at-home’ orders—only leave home for essential work; health, safety and caregiving; buying essential provisions; and permitted exercise within a specified travel radius

- a ’work from home’ directive for office workers

- closure of ‘non-essential’ businesses, including retail, travel, recreation, entertainment and hospitality; cafes and restaurants supplying take-away food only

- ‘remote learning’—attending on-screen classes from home—for primary, secondary and tertiary students

- mandated mask-wearing—initially for everyone from twelve years of age; later for everyone eight years and over.

During Victoria’s second, extended lockdown, harsher restrictions in metropolitan Melbourne also included a nightly curfew from 8 p.m. to 5 a.m. (SBS News 2020).

The lockdowns significantly affected the lives of children and families. In addition to the anxiety and fear of infection, upheaval in their daily lives and loss of personal contact with friends and extended family, children and adults were forced into an artificial situation—spending all day, every day, together: no weekend activities, every day was the same. It was ‘blursday, when your days are blurry because you’ve been in your house for too long’—the blended word submitted to the Pandemic Play Project by an eight-year-old girl, and featured in the Oxford Dictionary’s list of defining words for 2020 (Oxner 2020). For families living in Melbourne through winter and spring of 2020, this extraordinary living arrangement lasted four months.

In June 2020, after Australia’s first lockdown and prior to Victoria’s second, extended lockdown, the Australian Childhood Foundation and the Royal Children’s Hospital Melbourne each undertook a national survey into the effects of Covid-19 on families. Survey respondents were parents or carers of children mostly aged from three to seventeen years. The reports reflected variations in the parameters of each study but both were consistent in several of their findings, including the pandemic’s negative effects on children’s mental health and well-being, a significant increase in children’s screen time, and an overwhelming number of children (eight out of ten) who missed their friends. While family experiences in lockdown were not all positive, the majority of parents in both studies felt their relationship with their children had become closer and they valued the extra time spent with them—more time ‘reading, playing games and eating meals together’ than before the pandemic (Royal Children’s Hospital 2020: 7; Tucci, Mitchell, and Thomas 2020).

Many children also valued the extra time spent with their parents, as revealed in studies from several countries (Gray 2020; Holt and Murray 2021; Smith et al. 2022; Stoecklin et al. 2021). ‘I spent more time with Mummy and Daddy’ was one of the activities listed by an eight-year-old girl in her submission to the Pandemic Play Project, along with others like reading, learning magic tricks, having an ‘Easter egg treasure hunt with clues’ and going for ‘lots of very, very boring walks’. Playing board and card games, doing puzzles and craftwork, cooking, singing silly songs, watching TV or movies and sharing jokes and riddles at mealtimes were some of the ways families came together during lockdown. As one child wrote: ‘We stayed home and found new ways to play’.

Lockdown also changed the way some parents perceive play. Living so closely as a family gave parents a unique opportunity to observe how children interact with each other and their environment in play, and to sometimes be allowed to join in their games. One father described how his nine-year-old daughter introduced him to Minecraft, ‘When remote work and remote school had finished for the day’,

the first thing she would ask is, ‘Dad, is your iPad upstairs?’ With the game loaded up on our iPads and connected to the same household LAN, we could see each other as a ‘Friend’. She created a […] peaceful ‘Dad Learning’ world on my device and was able to join me in the game to show me how to find the menu with all the different materials and objects available, and how to create a building with windows, open and close doors and even fly! She also created other worlds on her device and built houses for us to share while we explored and created all kinds of wonderful things together. Sharing screen time in this manner […] has been a lot of fun and has enabled me to spend time playing with her in a very different environment compared with the card and board games we have been utilizing up until now.

Cohen and Bamberger (2021: 6-12) recount Israeli parents’ spontaneous descriptions of the way their children, aged three to nine years, played during the pandemic, with parents commenting on developmental changes or adaptations to play, and the way the children expressed their feelings and understanding of Covid through their play activities.

Conversely, having adults around all the time can inhibit play. Children need time, space and freedom to play in their own way. ‘The role of adults’, according to Dodd and Gill (2020), ‘is to provide physical and psychological space, and resources that support the child’s play. They should only join in or interfere with the play if the child asks them to’. With adults working from home and children studying and playing at home, space often had to be negotiated. In unit blocks and apartments, the close and continual proximity of adults to children, who are usually at school all day, sometimes provoked disputes over the use of shared spaces (Foster 2020). Play Australia underlines the importance of separate playing spaces: ‘Allowing children to create a space of their own where they can retreat to and indulge in play, is an important step in them reclaiming some power and control over their environment’ (Miller 2022: 2).

A widespread response to lockdown in Australia was the relaxing of the usual household rules by parents. In contrast to a common family hierarchy where ‘Adults generally define the purpose and use of space and time [and] children usually find ways to play that appear within the cracks of this adult order’ (Lester and Russell 2010: ix), there seemed to be an early acceptance by many parents that play was important for their children, and that adjustments needed to be made to their usual way of living. Save the Children (2021a) offered sage advice about what was to come:

Be prepared for your days to be messy. There may be days when the home becomes a messy play area, or working parents rely on TV more than usual. While lockdown continues for the next few weeks or months, a little chaos is to be expected.

Bending the rules allowed children to wear their roller blades inside the house; eat snacks on the trampoline; take over whole rooms to build cubbies and box forts; move cushions, mats and furniture to make obstacle courses; and lay long, wobbly trails indoors for a game of ’The Floor is Lava’. In this game, players make their way along the trail, trying to reach the end without overbalancing and stepping into the ‘lava’. The game becomes more exciting when there is a ‘Lava Monster’ ready to disrupt play by displacing the trail or unbalancing someone into the ‘lava’.

Children’s experiences of lockdown, and their opportunities for play, depended on where they lived, and to a greater extent on their socio-economic situation. Families living in poverty do not have the extra income to order board games, puzzles and other resources online. Lockdown intensified already-existing inequalities for children and families, particularly in metropolitan Melbourne. For children living in high-rise public housing towers these included access to digital resources, play materials and safe outside playing spaces. Lockdown was a test of their resilience and perseverance against sometimes overwhelming odds. Large families, cramped living conditions and lack of access to the outdoors made lockdown unbearably challenging for children and families living in the flats.

The following is a personal narrative by Danni von der Borch, a senior playworker at The Venny Inc., one of five staffed adventure playgrounds in Australia and, in ‘normal’ times, the communal backyard for children living in nearby public housing towers. The towers are home to residents on low incomes and people of culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds, including refugees who have escaped war and conflict overseas. Local community languages, apart from English, include Amharic, Tigrinya, Arabic, Oromo, Somali, Vietnamese and Mandarin.

The Venny’s Response to Lockdown: A Case Study

In March, 2020, when Australia’s first lockdown was imminent, we spent time with the children we work with, practising what it might be like to be distant but still together; preparing them, and ourselves, for something unknown which was about to unfold. We danced in separate parts of the yard—dancing alone and separate but still connected. It was autumn and the fading afternoon sun gave us warmth and a glow; the music was loud and we danced. We were preparing for when we would have to be apart from each other and for when The Venny would have to close. We practised ‘self-hugs’, feeling the presence of each other but not being together. Adults and kids sharing the same unknown future.

Moving to online sessions seemed like something from a nightmare—being in a virtual world with each other, not in a relational experience but one mediated via technology and a computer screen. We all felt acutely the weight of responsibility, asking, ‘How will we continue to play?’ ‘How can we connect with The Venny children and provide the goodness we know they get from playing?’ We just had to get creative and find the ways. And we did. Throughout every lockdown in 2020–21, The Venny provided three online play sessions a week.

Children and families across Melbourne had to adjust to online remote learning, and the demands of this left kids feeling drained. We felt awful asking them to show up for yet more screen time—play sessions with us. This led us to wonder about points of connection and how we could ‘stay in touch’, particularly with kids who don’t have their own phone or access to devices and unlimited data. How could we extend our presence, our reach, whilst still complying with lockdown rules? The answers came in several forms:

From the first lockdown we recognized the need for children to have things to do and a focus for play, during their many hours indoors. We put together and delivered weekly Play Packs to children living in local public housing in Kensington, North Melbourne and Flemington. We wanted to make sure everyone had the resources they needed to join in with our online sessions. Each pack came in a hand-folded origami newspaper bag—this inspiration came early to avoid plastic bags. The origami bag served a dual purpose—when unfolded the newspaper became a working surface for doing messy art/clay/craft activities. Win-win! My aunty took on the task of regularly folding bundles for us to use, relying on friends to donate their newspapers. We were so grateful.

Our first pack was for making ‘Grass Head Creatures’, so children had something to tend to, watching it change and grow over the days and weeks ahead. We often made ‘how to’ videos connected to the Play Packs, so children could do the activity when it suited them and away from the screen. These videos, photos and messages were posted on our social media platforms, Facebook and Instagram. We also used WhatsApp chat groups with residents to share information and keep in touch.

The ‘Hard Lockdown’

On 4 July, 2020, about three thousand people in nine local public housing towers were placed under an immediate, police-enforced ‘hard lockdown’. No-one was allowed into the towers and no-one was allowed out (McKinty and Hazleton 2022: 4). After five days, eight of the towers were released—people living in the ninth tower were kept inside their homes for a further two weeks, ‘unable to attend work, visit the supermarket or, for the most part, access fresh air and outdoor exercise’. Almost half were children under eighteen years (Glass 2020: 12, 36).

Through our local connections and deep relationships, The Venny played a crucial role in providing sensory play and art activity packs for children experiencing the hard lockdown. Within days of the 4 July directive, The Venny was overwhelmed with donations of play and art/craft materials, books and toys, as well as financial donations to help support our ongoing work. Within the week we were able to mobilise volunteers and, with the support of Artists for Kids Culture, pack 220 bags for delivery to the towers. Already embedded on the ground at the North Melbourne incident control site, and with support from the City of Melbourne, The Venny staff were able to manoeuvre our way into the delivery schedule, to make sure the Play Packs were delivered to children within the towers. This contact remained once the hard lockdown was lifted, with direct deliveries to children and young people continuing.

Letter Boxes

During the first week of lockdown, a young girl was outside The Venny, leaning on the shipping container. We saw each other and she said to me:

I’m lonely.

There’s no one to play with.

I come here every day. I give The Venny a hug and say ‘I hope you get well’.

It’s so awful,

Mum’s in her room,

My brother is out,

I’m on my own.

I wrote a letter to you, but I didn’t know how to post it to you.

We began thinking about how old-fashioned letter-writing and posting was another way to connect. The children could post a letter to us and we could leave replies or treasures in the boxes for them to find. And yes, there were discussions about what sort of surfaces or objects might be Covid carriers and if we needed to do infection control cleans and processes around what went into the letter boxes.

Quite by chance, on the last, anxious day before lockdown, I saw a man working in his garage making toys from scrap wood. I stopped, feeling unsure if my lingering would be welcomed or not, but he was so warm, so friendly, and reminded me of my own dad. He showed me what he called ‘snappy boxes’—essentially a hinged box with eyes, and when you opened it, inside were teeth. I immediately thought these would make perfect letter boxes. He agreed to make us a few and refused to accept any payment. We attached the letter boxes to posts in the bushes outside The Venny fence—secret boxes that would inspire play and connection to the physical site of The Venny, and also allow for communication that was not digital but in the form of magical trinkets, chalk, high bounce balls, pictures, drawings, postcards and poems.

Using Zoom for Online Play: What We Did and How We Played

Moving to Zoom, one of the core questions for us as playworkers was how to continue to allow kids to ‘lead the play’; and if we were the content creators, providing the play packs and activities, how would that influence children’s play? From the outset we thought a lot about the Zoom platform and its functions. We discussed the power of the ‘Host’ role and the ‘mute’ button—the total inverse of the child-led and shared power situation we most want to encourage in the face-to-face play environment. Rather than simply taking that power as the Host to mute participants, we developed a hand signal, waggling our fingers, that the children would mirror, so there was a moment of shared participation and forewarning before muting. It was a small thing but one that allowed us to collaborate and share the power together.

We considered the child safety protocols of using online: the Zoom ID was disseminated directly to children we knew via a verified contact—it was never shared on social media or the website. For the sessions we set up a separate ‘welcome room’, where two staff verified the identities of kids entering the Zoom session. Once welcomed, they were sent through to ‘the yard’ where all the other staff were and where the action happened.

In the first weeks of lockdown children were exhausted by too much screen time—with remote online learning and then more online programmes. They often began a session with low energy, looking drained and sad, so we quickly realized that we needed to get them active, discharging and expressing emotions. One session was a giant pillow fight to some fun music, and at the end kids were lively, chatty, being funny, playful and relaxed. We included dancing in most sessions and invited kids to offer a song for the play list. This brought joy and happiness to the session.

We wanted to encourage ‘soft attention’ at times—not always having to look at the screen but rather to focus on their own activity, i.e. drawing and painting together and then sharing whenever they wanted to. The focus was often sensory, creative play and art-making, but also silly and irreverent fun, jokes and quizzes and sharing stories. We often invited kids to use their voices—be vocal, sigh loudly, beat their chests, make sound, be loud—just to feel the release of this. We would often pull faces, stick our tongues out and invite silliness—no performance required here—no ‘be good’ and attend.

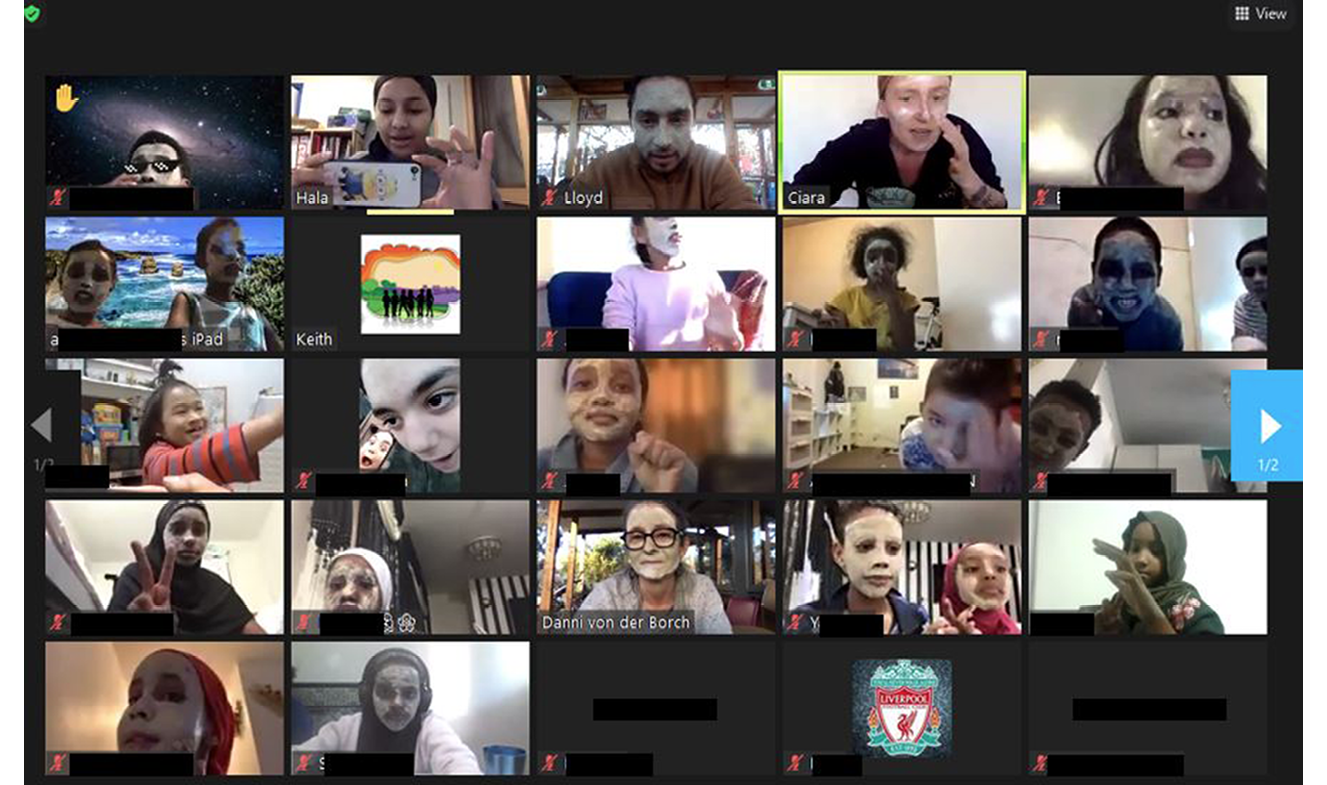

Clay was always popular, creating creatures or landscapes and objects. A ‘corona-free cubby’ was an invitation that led to the creation of places beyond the world of corona—several islands were made, lots of water and swimming, a boat with a hammock, an elephant, a turtle, a whole world with everything you need (even a Venny!). Our creatures and characters met each other, and stories were developed and shared. Watered-down clay was made into mud to paint our faces.

Figure 16.1 ‘Mud on our Face’, Children playing ‘together apart’ during The Venny’s ‘Mud on our Face’ online play session over Zoom, 2020

Screen image by Danni von der Borch, courtesy of The Venny Inc., CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

One session we put a torch, cellophane, rubber bands and sticky tape in the Play Pack and played around in the dark. We used the newspaper bag to make a lantern cover for the torch, cutting shapes in the bag and covering them with coloured cellophane. Kids went crazy!! They hid in wardrobes and cupboards, shut themselves in bathrooms, hung blankets over bunk beds, went under beds and made cosy blanket cubbies. They danced and swung their lights around in a frenzy of frenetic dancing at the disco. They also played with their own video screens a lot—watching the weird distortions of light and shadow on their faces—making scary faces at each other. It was a happy riot.

Another time we gave extra newspaper, coloured paper and masking tape, and used this to make wearable ‘statement pieces’, and the creative energy was wonderful—hats, boots, shoes, headdresses, a lantern, wigs and crowns. One child made a crown that let her teleport herself straight to where she needed to go—home, The Venny, supermarket, school, movies and home again—in that order.

Sand Trays

Sand trays formed part of The Venny’s considered play approach for children in lockdown. These could be used in the corridors of public high-rise buildings or in the living room. Sand is a sensory play experience that allows children to build worlds in the sand and to tell stories from this place. We sourced, assembled and delivered 110 sand trays during the lockdown period, including sand and small objects to play with. Venny staff interacted with children via online sessions to support their play and storytelling. The worlds the children created through their sand trays varied, from escape fantasy to confinement and lonely worlds. The response from parents was one of immense gratitude that their kids were able to lose themselves in playing for lengthy periods of time, and it was something that siblings could do together.

Respite Visits to The Venny

Small respite visits were held outdoors on-site during the end of lockdown in 2020 and again in 2021 when regulations and compliance allowed. These were limited to children who were deemed at greater risk due to demonstrated and deteriorating mental and emotional health, or who were in environments where the health and well-being of the adults they lived with had an adverse impact. This included children in environments where aggression was escalating. Using play as the primary tool, these children were supported to find their way back from traumatic experiences and make sense of their world again. This was empowering for these children and helped them to rebuild confidence and self-esteem, and regain a sense of control.

In one session a family of three children, aged eight, six and five years, took me and found a rope, tied my hands together and sat me on a chair. They used milk crates to build a wall around me, trapping me in. When I asked, ‘Are you closing me in?’ the response was fast and firm—‘Yes, you’ve been so bad’. I am in prison. The children’s roles in this game are police, security and a lawyer.

One of them brings a clock over and tells me that when it is six in the morning I will die. I ask, ‘What will happen?’ He says, ‘I will shoot you and you’ll go ahhhh, and then the police will throw you in the water’. The ‘lawyer’ finds a high stool and places it where she can watch from a high vantage point. The ‘security guard’ makes a point of squinting his eyes to look mean, puffing up his chest and saying, ‘I am so strong’. They set up a phone on the chair so I can speak with the ‘lawyer’. I am required to plead to all sorts of crimes, including murder. This game continues the next time they visit and when they want to go off and explore other things, they set up a ‘security surveillance camera’, switching it on and telling me it’s connected to a ‘wristwatch’ that one of them is wearing, so they would ‘always know’. This deep play continued over several consecutive sessions and became a vital part of these children’s processing of experiences endured.

We have attempted to find connection, play and creativity with all the children of The Venny community. We welcomed many new kids and families during and after the hard lockdown and did outreach with these kids to ensure they were included and welcomed. We found a way to exchange energy, to play and bounce off each other, to encourage kids to lead and to open their imagination and for a small time lose themselves in play.

2. Children’s Creativity, Imagination and Resourcefulness

In 2020, almost all children in Australia experienced being in lockdown. The patterns of their lives at this time were similar to those of children in other parts of the world (Graber et al. 2020; Holt and Murray 2021; Stoecklin et al. 2021). Freed from the pressures of time-driven daily living, children found they could explore new options for extended play. This influenced outdoor play, and included the appropriation of public spaces. In local parks, neighbourhood streets and on remarkably car-free roads, traces of play were seemingly everywhere as children found creative and sometimes unusual ways to stay playful and resilient. While enjoying, or enduring, daily exercise outings with their parents, Melbourne children explored their local streets—young children rode bikes and scooters along the footpaths, stopping at the kerb to let the adults catch up. Free-wheeling groups of older children, mainly boys, often met at their local parks to ride their bikes, climb trees and play.

One of these meeting places was an early 1900s Melbourne suburban public garden, with an open, grassed sports oval at one end and thirteen acres (five hectares) of shady tree-lined avenues with shrubs, planted gardens and grassed areas at the other. There, in the tree area (‘the park’) away from the sports ground, four boys, aged nine to ten years, began meeting on weekday afternoons after remote schooling. Initially they simply rode their bikes in the park, along the gravelled walkways or across the loose earth around the park’s perimeter. Then, with growing confidence, they decided to make ‘jumps’ by piling mounds of loose earth in the park nearest the streets where they lived. This created an informal bike track. The word spread rapidly along the children’s grapevine and soon others were riding their bikes to the park more often. Pioneers and newcomers banded together to form a flexible cohort of between ten and twenty boys aged around eight to eleven years.

The bike track was extended around the park perimeter, with jumps at intervals. On weekends, and during school holidays-at-home, children gathered under a large, shady tree, with bikes strewn on the ground, to plan the day’s riding. Someone usually brought a small shovel to repair the jumps. On days when the park was busy a few parents, some also on bikes, went along to keep a benevolent eye on the interaction between riders and walkers. The parents seemed somewhat bemused by their children’s intense and prolonged engagement with this activity. The bike tracks were used by any child on wheels, including scooters: they added risk, challenge and fun to the day’s outing, with opportunities for extended play. The park was their chosen place to play; in creating the bike tracks the boys shared their play experience with other children. Their appropriation of space around the margins of the park had inadvertently added the word ‘play’ to the list of reasons to leave home during lockdown.

At any other time, this subversive activity would not be tolerated. Public parks are designed by adults with adults in mind, and children are usually relegated to the swing sets and climbing equipment in designated playing areas. Occasionally traces of play can be found among the shrubs but these are usually quite small, personal and ephemeral. The fact that the bike-track boys could openly claim their territory and alter the space to play in their own way, within a public park, was intrinsically connected to the lockdown. The tolerant attitude of adults in the park was a reflection of the relaxed approach to play found in family homes during this time.

Perhaps a clue to the mindset, and exceptional tolerance, of the council in charge of the ‘bike-track’ park can be found in the playful wording of a temporary sign placed beside the oval, a popular place to exercise dogs:

ATTENTION ALL DOGS

This is the Central Park oval and the designated dog off-leash area.Ask your human to let you off-leash here so you can go for a run and explore!Please remember you are only allowed to be off-leash if you promise to be a good dog and listen to your human. And, remember you must be on your leash in all other areas of Central Park. Have fun, good dog !

Unfortunately, the lifespan of other informal bike tracks depended on the attitude of local councils. The bike track and jumps described above remained (and were maintained by the children) for most of the long, second Melbourne lockdown, which lasted for four months. In another large Victorian regional city, a smaller bike track, with a few jumps, was quickly removed by council workers. This conflict between children attempting to make their own play spaces and the authorities in charge of public parklands is vividly described by Sleight (2013: 61), who evokes the streets and open spaces of nineteenth- and early twentieth-century Melbourne, and describes ‘the most concerted attempts by the city’s youngsters to refashion the landscape to suit their purposes, attempts that met with determined efforts by trustees to prevent damage’.

Figure 16.2 ‘Spoonville, Glen Iris (2020)’, one of the many ‘Spoonvilles’ created by children in local parks and neighbourhoods during lockdown

Photo by Judy McKinty, CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

Another example of children appropriating public space was the emergence of ‘Spoonvilles’, groups or ‘villages’ of mainly wooden spoons, decorated with coloured markers and craft materials like beads, pipe cleaners, googly eyes and fabric scraps to look like people (Boseley 2020). ‘Spoonvilles’ were omnipresent, appearing on nature strips (grass strips alongside footpaths), in front gardens and—a particularly favoured place—at the base of trees in public parks. Children made their spoon people at home and carried them to the local park, placing them upright beside characters made by other people. This gave children a sense of connection and a chance to display their craft work in public. Like the bike track above, ‘Spoonvilles’ were tolerated by local authorities and remained largely undisturbed during lockdown. In one park, a playfully contrary group of children responded to this global craze by creating a ‘Forkville’ on the other side of the tree.

Children chalked rainbows, colourful patterns and messages on footpaths, driveways and in the middle of the road (‘Careful of Kids’). The appearance of hopscotches on public walkways turned local streets into community play spaces, where everyone could join in. One nine-year-old girl drew hopscotch patterns on the footpath and wrote how to play on papers she pinned to a tree. Among the patterns were ‘Stepping Stones’—a line of shapes for people to walk along—and ‘Dog Scotch’, where the shapes were paw prints, for dogs to play.

The International Play Association (2017:14), in supporting children’s right to play, states:

An optimum play environment is […] a trusted space where children feel free to play in their own way, on their own terms. Children’s spaces should include chances for wonder, excitement and the unexpected and, most of all, opportunities that are not overly ordered and controlled by adults. These spaces are crucial for children’s own culture and for their sense of place and belonging.

3. The Importance of Children’s Own Culture and Play Traditions in terms of Expression and Responses to Covid

Traditional Play and Technology During the Pandemic

When children are old enough to socialize meaningfully with their peers, they become immersed in their own unique culture. Thriving largely beneath the gaze of adults, childhood culture is at once structured, grounded in tradition and innately embedded in the experience of childhood itself and simultaneously adaptable, constantly evolving, responsive and connected to the immediate world in which we live (Seal 1998: 92).

Children’s play culture passes from child to child and includes verbal lore (such as jokes, rhymes, subversive humour and chants) and games (imaginative games, dress-ups and role play, physical challenges, and schoolyard games like Hide and Seek, and Chasey). Children’s traditional play has roots in ancient culture and is enthusiastically adopted by children worldwide regardless of cultural, geographic, historical and socioeconomic boundaries (Opie and Opie 1977: 22-23). One of the most significant findings from our project has centred around the relationship between technology and traditional play in the lives of children during lockdown. At a time when children were separated from their peers and suffering ongoing uncertainty, they quickly and masterfully adapted the digital realm and technology to maintain their own play culture.

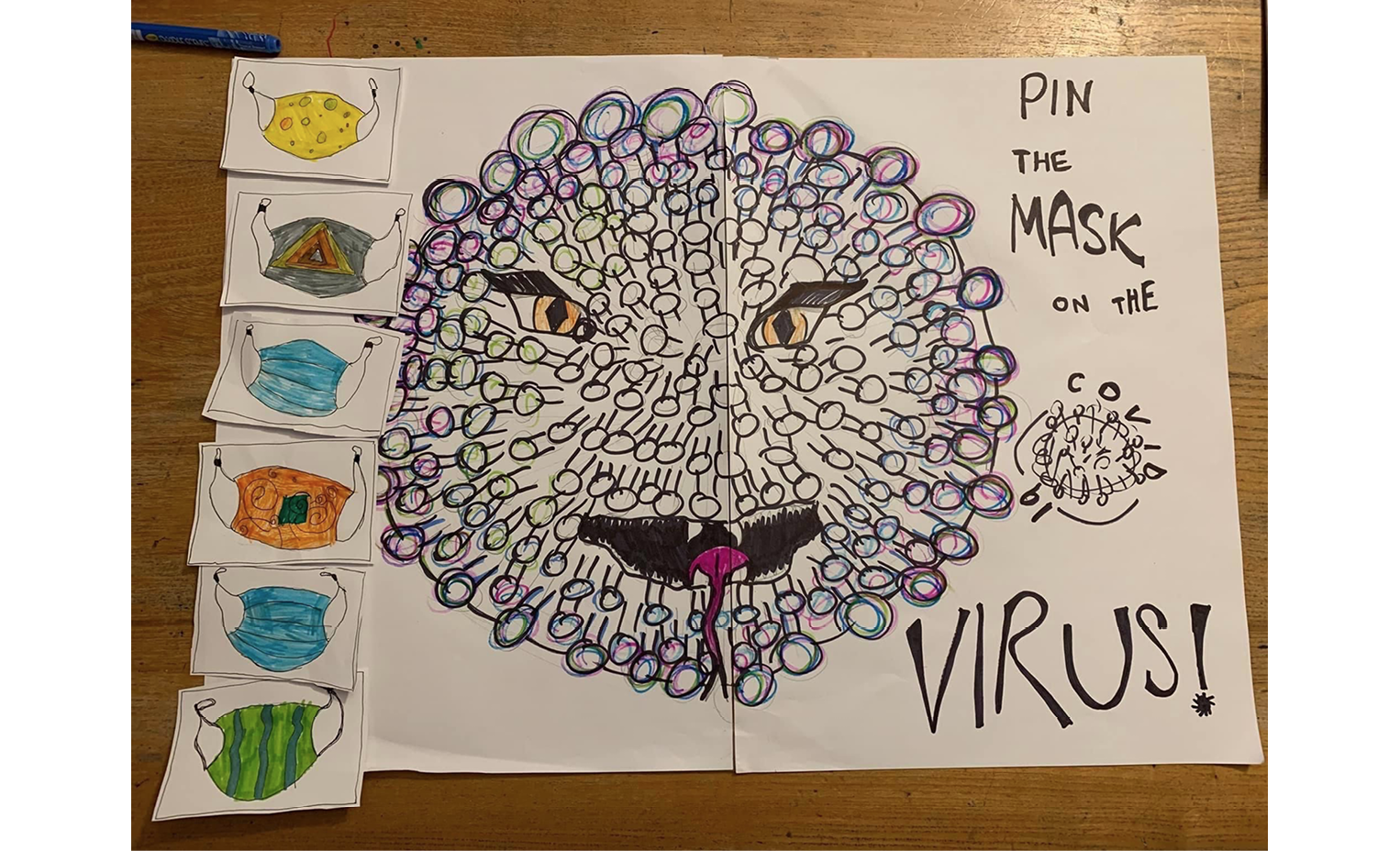

Figure 16.3 ‘Pin the Mask on the Virus game (2021)’, a Covid-19 adaptation of the traditional blindfold game Pin the Tail on the Donkey, created by two children, aged eleven and nine, for a birthday party

Photo by Kate Fagan, CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

Having to endure prolonged periods of lockdown inflicted many families with a profound sense of loss in terms of physical space and social connectivity. Adults not considered ‘essential workers’ were required to work from home, while children and older students navigated online classes, sometimes all within the same space. The household became an environment in which separate spheres of life suddenly collided. Requiring access to multiple devices and familiarity with new platforms, digital technology became integral to day-to-day life—a situation previously unimaginable to most households. Families from disadvantaged backgrounds were loaned basic digital resources for use at home; access to reliable internet became essential, but inconsistent network connections and sub-standard devices meant that inequities became increasingly apparent. At the other end of the socio-economic spectrum, sales of gaming consoles rose almost three hundred percent in the space of one fortnight in March 2020 as life in lockdown commenced (Dring 2020).

Extended screen time became unavoidable. Not only were children exposed to significantly increased screen usage for education, they also relied more on technology to entertain themselves and maintain their social lives and friendships. For Australian parents and caregivers, this was not easy to accept, due to dominant cultural narratives around the negative impacts of ‘screen time’ on children’s health, fitness, socialization, safety, cognitive development and mental health (Walmsley 2014). Anticipating that increased use of technology during the pandemic would exacerbate these fears, UNICEF published an article urging adults to re-think their attitudes toward the household use of devices and acknowledge the benefits of online connectivity for children (Kardefelt, Winther and Byrne 2020). Basically, we were required to re-think the common assumption that ‘proper’ play belongs only within the sphere of the physical playground.

Our findings have mirrored those of other studies in concluding that digital play is not separate from, but rather an extension of, traditional physical play and that traditional forms of play feature regularly in the digital realm (Mavoa and Carter 2020: 2-3). We observed this within three distinct contexts: verbal play, hybrid play and in the digital playground itself. We also identified one key factor, not in common use prior to the pandemic, that allowed play to flourish as brilliantly as it did—the use of Voice over Internet Protocol (VoIP) platforms such as Zoom, Kids Messenger and Discord.

Once a platform for business, international communications and serious gaming communities, video-conferencing became a common tool for facilitating regular interaction between friends and family during lockdown (Cowan et al. 2021: 12). Many parents admit to being completely unaware, before the pandemic, of the available platforms allowing real-time conversation for children, other than FaceTime, Zoom, Microsoft Teams or Skype. Navigating the creation of email and platform accounts, and negotiating access guidelines and security settings for their children, proved a very steep learning curve for many parents. The initial stages of enabling these networks was a source of great challenge and frustration for some.

Eventually, previous generations’ experience of a knock on the door followed by ‘Can you play?’ was signalled during lockdowns by the sound of a device alert. The sound of children’s voices once again filled isolated households—this time virtually instead of physically. Children’s traditional play is very much a transactional experience. The glee in the telling of a naughty joke or rhyme is greatly reduced if there is nobody present to appreciate the deliciousness of the subversive humour (and adults often just do not ‘get it’). Without access to peers, a vast pool of play becomes less meaningful or simply disappears. Being able to communicate in the moment, embrace spontaneity and engage with the natural ebb and flow of play decisions is fundamental to traditional play in childhood, and VoIP platforms proved to be the perfect conduit. In utilizing these, play became more immediate, cooperative and fluid (McKinty and Hazleton 2022: 14). In terms of verbal play, the use of VoIP platforms allowed children to interact as they might in the playground. Not only could they now relish their sayings, jokes, rhymes, insults and slang in real-time, they could explore their experiences of the pandemic together in an almost in-person way.

Living 3,700 kilometres (2,300 miles) and three time zones apart in Melbourne, Victoria and Geraldton, Western Australia, Charlie and Lola (both aged ten) developed an almost daily friendship that included using tablets and smartphones. Together they conducted physical jumping competitions, cooked, and carved Halloween pumpkins together. They took photos and videos of each other, added effects using downloaded applications and relished the joys of playing with silly and distorted images. Other children used video conferencing to host and attend ‘playdates’, ‘crafternoons’, birthday parties and ‘game dates’. Such occasions became regular and much-anticipated moments of personal contact, mimicking pre-pandemic life in a virtual context.

From Sydney, New South Wales, one mother described her daughter and friends playing a spontaneous game of online Hide and Seek. The person who was ‘hiding’ would either describe the furniture in various rooms or give the group a visual tour of rooms nearby. They would all then take turns guessing where the imaginary hiding place was until one child guessed correctly and became the next person to ‘hide’. In another example, a four-and-a-half-year-old girl from regional Victoria displayed her inherent talent for imaginative play when she placed her grandparents (who were online from the UK via tablet) into a cardboard box and ‘flew’ them through the air. In the video submission, she is dragging the box across the floor and pretending they are all flying in an aeroplane.

In all of these activities we see examples of ‘hybrid’ play, where play is initiated in the physical world while simultaneously utilizing video and audio communications technologies (Cowan 2021). In the digital realm, VoIP platforms enabled a much deeper cooperative play experience, particularly within immersive games like Minecraft and Roblox. As distinguished from single-player games and games dependent on structured progress and narratives, games like Minecraft and Roblox are essentially virtual playgrounds. Considered ‘sandbox games’, players have infinite control over their virtual environments in terms of building and shaping their own worlds and gameplay.

The nature of sandbox games does not limit the use of human imagination. In engaging with this kind of play,

the intangibility of children’s imagination is not only laid over inert but compelling material, it is also delegated to machinic analogues. This process by no means replaces human imagination, as the critics of digital play might have it; it extends and augments it—rendering it poorer in some aspects but opening all sorts of new games and meta-games. (Giddings 2014:127)

Access to VoIP platforms has enabled sandbox games to become the perfect emergent spaces for combined play and socialization (Rospigliosi 2022: 2). Game rules and protocols can be negotiated and developed spontaneously, game objectives identified, and cooperative strategies can be debated and agreed upon in real-time. In games like Roblox and Minecraft, where players can build and create their own games and ‘clubs’, the theme of Covid was an immediately discernible feature of the virtual playground. Hospitals and anti-virus armies were created in response to the pandemic. Quests and missions designed to hide from Covid were plentiful and, interestingly, avatars wore masks and attire reflecting common anxieties about the pandemic.

In the context of pandemic play, these avatars (or online identities) have been used in a very simple and similar way to the age-old game of ‘dress-ups’. Within our submissions, we documented masks on Barbie dolls and a real-life dress-up character, ‘Captain Covid’, alongside a cohort of digital figures wearing masks and Covid t-shirts in the virtual playground. The simultaneous curatorship of individual and group digital identities is a remarkable illustration of how children flipped the frameworks of traditional play and responded to the pandemic in a very powerful way.

Despite the confines of lockdowns, access to technology enabled children to continue to engage with their own traditional play culture, also allowing them to develop a sense of agency against the unknown and do so collectively—with their peers and beyond the boundaries of the family home and local streets. We would also argue that the use of VoIP platforms has fundamentally and permanently changed the play landscape for many children growing up in the pandemic, adding new dimensions of connectivity and opportunity that will still be in popular use after the pandemic has passed on.

Conclusion

Children’s experiences of play in lockdown were influenced by a very broad range of variables including their age, where they lived, who they lived with, their access to play resources including digital equipment and the internet, their socio-economic situation, support from adults, and connection to friends. Rules were relaxed to support playfulness at home and in the streets and parks of local neighbourhoods.

Yet the critically important role of play in times of crisis was fully revealed in the warm, caring, mindful and supportive relationship between local playworkers and some of the most disadvantaged and traumatized children in the city—those who live in cramped flats in Melbourne’s high-rise public housing towers. This is the true power of play.

Works Cited

BBC News. 2020. ‘Coronavirus: The World in Lockdown in Graphs and Charts’, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-52103747

Boaz, Judd. 2021. ‘Melbourne Passes Buenos Aires’ World Record for Time Spent in COVID-19 lockdown’, ABC News, https://www.abc.net.au/news/2021-10-03/melbourne-longest-lockdown/100510710

Boseley, Matilda. 2020. ‘“A Form of Connection”: Spoonville Craze Revives Community Spirit in Australia’, The Guardian, https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2020/sep/02/a-form-of-connection-spoonville-craze-revives-community-spirit-in-australia

Brown, Stuart. 2010. Play: How It Shapes the Brain, Opens the Imagination, and Invigorates the Soul (New York: Avery Books)

Cohen, Esther, and Esther Bamberger. 2021. ‘”Stranger-Danger”: Israeli Children Playing with the Concept of “Corona” and Its Impact during the COVID-19 Pandemic’, International Journal of Play, 10, https://doi.org/10.1080/21594937.2021.2005398

Cowan, Kate. 2021. ‘Play Apart Together: Digital Play During the Pandemic’, https://play-observatory.com/blog/play-apart-together-digital-play-during-the-pandemic

Cowan, Kate, et al. 2021. ‘Children’s Digital Play during the COVID-19 Pandemic: insights from the Play Observatory’, Journal of e-Learning and Knowledge Society, 17: 8-17 https://doi.org/10.20368/1971-8829/1135583

Dodd, Helen, and Tim Gill. 2020. ‘Coronavirus: Just Letting Children Play Will Help Them, and their Parents, Cope’, The Conversation, https://theconversation.com/coronavirus-just-letting-children-play-will-help-them-and-their-parents-cope-134480

Dodd, Henry. 2020. ‘I Can’t Believe I Am Going to Say This, but I Would Rather Be at School’, The New York Times, 14 April, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/14/us/school-at-home-students-coronavirus.html

Dring, Christopher. 2020. ‘What Is Happening with Video Game Sales during Coronavirus?’ GamesIndustry.biz, https://www.gamesindustry.biz/what-is-happening-with-video-game-sales-during-coronavirus

Fernando, Gavin. 2020. ‘Is Melbourne’s Coronavirus Lockdown Really the Longest in the World? Here’s How Other Countries Stack Up’, SBS News, https://www.sbs.com.au/news/is-melbourne-s-coronavirus-lockdown-really-the-longest-in-the-world-here-s-how-other-countries-stack-up

Foster, Sophie. 2020. ‘Coronavirus: Kids Playing, Riding Bicycles Spark Building Disputes’, realestate.com.au, 28 April, https://www.realestate.com.au/news/coronavirus-kids-playing-riding-bicycles-spark-building-disputes/

Giddings, Seth. 2014. Gameworlds: Virtual Media and Children’s Everyday Play (New York: Bloomsbury Academic), https://doi.org/

Glass, Deborah. 2020. ‘Investigation into the Detention and Treatment of Public Housing Residents Arising from a COVID-19 “Hard Lockdown” in July 2020’ (Victorian Ombudsman), https://www.ombudsman.vic.gov.au/our-impact/investigation-reports/investigation-into-the-detention-and-treatment-of-public-housing-residents-arising-from-a-covid-19-hard-lockdown-in-july-2020/

Graber, Kelsey, et al. 2020. ‘A Rapid Review of the Impact of Quarantine and Restricted Environments on Children’s Play and Health Outcomes’, PsyArXiv Preprints, https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/p6qxt

Gray, Peter. 2020. ‘How Children Coped in the First Months of the Pandemic Lockdown: Free Time, Play, Family Togetherness, and Helping Out at Home’, American Journal of Play, 13, https://www.museumofplay.org/journalofplay/issues/volume-13-number-1/

Holt, Louise, and Lesley Murray. 2022. ‘Children and Covid-19 in the UK’, Children’s Geographies, 20: 487-94, https://doi.org/10.1080/14733285.2021.1921699

International Play Association. 2017. ‘Access to Play in Crisis Toolkit’, Play: Rights and Practice: A Toolkit for Staff, Managers and Policy Makers, https://ipaworld.org/resources/

Kardefelt Winther, Daniel and Jasmina Byrne. 2020. ‘Rethinking Screen-time in the Time of COVID-19’, UNICEF, 7 April, https://www.unicef.org/globalinsight/stories/rethinking-screen-time-time-covid-19

Lester, Stuart, and Wendy Russell. 2010. ‘Children’s Right to Play: An Examination of the Importance of Play in the Lives of Children Worldwide’ (International Play Association), https://ipaworld.org/ipa-working-paper-on-childs-right-to-play/

McKinty, Judy. 2020. ‘Pandemic Play Project: Project Background’, https://pandemicplayproject.com/About/

McKinty, Judy and Ruth Hazleton. 2022. ‘The Pandemic Play Project—Documenting Kids’ Culture during COVID-19’, International Journal of Play, 11: 12-33, https://doi.org/10.1080/21594937.2022.2042940

Mannix, Liam. 2020. ‘The World’s Longest COVID-19 Lockdowns: How Victoria Compares’, The Age, https://www.theage.com.au/national/victoria/the-world-s-longest-covid-19-lockdowns-how-victoria-compares-20200907-p55t7q.html

Mavoa, Jane and Marcus Carter. 2020. ‘Child’s play in the time of COVID: Screen games are still “real” play’, The Conversation, https://theconversation.com/childs-play-in-the-time-of-covid-screen-games-are-still-real-play-145382

Miller, Robyn Monro. 2022. Children, Play and Crisis: A Guide for Parents and Carers (Play Australia), https://www.playaustralia.org.au/category/resource-type/pdf-document-download

Opie, Iona, and Peter Opie. 1977. The Lore and Language of Schoolchildren (London: Granada)

Oxner, Reese. 2020. ‘Oxford’s Defining Words of 2020: “Blursday”, “Systemic Racism” and yes, “Pandemic”’, National Public Radio (NPR), https://www.npr.org/2020/11/23/938187229/oxfords-defining-words-of-2020-blursday-systemic-racism-and-yes-pandemic

Pandemic Play Project. 2020. ‘About/The Project/Who We Are’, https://pandemicplayproject.com/About/

Play Wales. 2014. What Is Play and Why Is it Important? https://www.playwales.org.uk/eng/publications/informationsheets

Rospigliosi, Pericles ‘asher’. 2022. ‘Metaverse or Simulacra? Roblox, Minecraft, Meta and the Turn to Virtual Reality for Education, Socialisation and Work’, Interactive Learning Environments, 30: 1-3, https://doi.org/10.1080/10494820.2022.2022899

Royal Children’s Hospital Melbourne, 2020. RCH National Child Health Poll 18. Covid-19 Pandemic: Effects on the Lives of Australian Children and Families (Melbourne: Royal Children’s Hospital), https://www.rchpoll.org.au/polls/covid-19-pandemic-effects-on-the-lives-of-australian-children-and-families/

Save the Children. 2020. ‘Life During Coronavirus: Missing School, Missing Friends’,https://www.savethechildren.net/blog/life-during-coronavirus-missing-school-missing-friends

Save the Children. 2021a. ‘Surviving and Enjoying Lockdown with Kids’, https://www.savethechildren.org.au/our-stories/surviving-and-enjoying-lockdown-with-kids

Save the Children. 2021b. ‘COVID-19: Children Globally Struggling after Lockdowns Averaging Six Months’, https://www.savethechildren.org.au/media/media-releases/children-globally-struggling-after-lockddown

SBS News. 2020. ‘Melburnians Spend First Night under Strict Curfew as Major Changes to Workplace Restrictions Expected’,https://www.sbs.com.au/news/article/melburnians-spend-first-night-under-strict-curfew-as-major-changes-to-workplace-restrictions-expected/6ga1nnd57

Seal, Graham. 1998. The Hidden Culture: Folklore in Australian Society (Perth: Black Swan Press)

Shooter, Mike. 2015. Building Resilience: The Importance of Playing (Play Wales), https://www.playwales.org.uk/eng/publications/informationsheets

Sleight, Simon. 2013. Young People and the Shaping of Public Space in Melbourne, 1870-1914 (Surrey: Ashgate)

Smith, Melody, et al. 2022. ‘Children’s Perceptions of their Neighbourhoods during COVID-19 Lockdown in Aotearoa New Zealand’, Children’s Geographies, https://doi.org/10.1080/14733285.2022.2026887

Stoecklin, Daniel, and others. 2021. ‘Lockdown and Children’s Well-Being: Experiences of Children in Switzerland, Canada and Estonia’, Childhood Vulnerability, 3: 41–59, https://doi.org/10.1007/s41255-021-00015-2

Tucci, Joe, Janise Mitchell, and Lauren Thomas. 2020. A Lasting Legacy: The Impact of COVID-19 on Children and Parents (Melbourne: Australian Childhood Foundation), https://www.childhood.org.au/covid-impact-welfare-children-parents/

Walmsley, Angela. 2014. ‘Backtalk: Unplug the kids’ The Phi Delta Kappan, 95(6): 80, https://www.jstor.org/stable/24374523