19. Art in the Streets:Playful Politics in the Work of The Velvet Bandit and SudaLove

© 2023, Heather Shirey, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0326.19

Art in the streets, and here I refer to graffiti, murals, stickers, paste-ups and other installations on walls, the pavement and signs, is uniquely positioned to respond quickly, effectively and sometimes playfully in a moment of crisis. Its placement in public space means that street art has the ability to reach a wide audience but to be effective it must be easily consumable in a single glance, speaking in a visual language that is clear and direct. In many places throughout the world, our movement in shared space was restricted due to the pandemic. In a time of social isolation, street art takes on additional significance as a form of communication and interaction.

By its nature, street art is interactive, engaging with people as they traverse the city. Art, like play, can serve to facilitate conversation and interaction. Like play, street art is frequently improvisational. Artists working in the street often approach their work in a playful manner, creating amusing and seemingly lighthearted images to capture attention. At the same time, street art is often used to express dissent in an oppressive political climate, frequently offering a critical assessment of the structural inequities and human rights issues that are exacerbated in a time of crisis (Konstantinos and Tsilimpounidi 2017; Awad and Wagoner 2017; Bloch 2020; Urban Art Mapping 2020). This critical stance may also be communicated in a playful manner, appearing lighthearted while conveying a serious political message.

This photographic essay is an examination of the work of two prolific street artists who address Covid-19 through art in the streets: The Velvet Bandit, a paste-up artist in Northern California, and Assil Diab, also known as SudaLove, a muralist who was working in Khartoum, Sudan, during the early months of the pandemic. These artists bring to us perspectives from two continents: North America and Africa. These two artists were working artists prior to the pandemic but both SudaLove and The Velvet Bandit expressed a new urgency to bring their artistic practice to the streets in the context of this global crisis. SudaLove created a number of murals in a short period of time in 2020 while The Velvet Bandit has continued to produce works addressing Covid-19, often interwoven with pieces addressing other issues such as Black Lives Matter, elections and reproductive rights.

In the works investigated here, both The Velvet Bandit and SudaLove create artistic interventions in the street as a means of engaging with Covid-19 in a manner that was light and playful but also serious and political. As is typical of street art, their work is highly accessible, using simple visual language. At the same time, each piece requires deeper contextual knowledge to understand the underlying political and social significance.

The interviews referenced in this photographic essay were conducted by members of the Urban Art Mapping research team, an interdisciplinary group that created and maintains the Covid-19 Street Art Database.

The Velvet Bandit

Based in Northern California, The Velvet Bandit’s artistic practice in the streets emerged in the context of the pandemic. While she always had a passion for art, it was not a full-time pursuit until spring 2020, when she was furloughed from her job in a school cafeteria. In a 27 January 2022 interview with Urban Art Mapping, The Velvet Bandit spoke to the idea that producing art can itself be both playful and an act of healing during traumatic moments: ‘When the pandemic first hit, I became unemployed and my two children were suddenly homeschooled, and I had nothing but my art supplies to keep me sane, to keep my children sane’ (Velvet Bandit 2022).

The Velvet Bandit creates small, original paintings on paper that are adhered to a surface with wheat paste. Each individual piece is usually referred to as a paste-up. The Velvet Bandit paints in acrylics, creating bold and colourful imagery, often accompanied by text. Typically, a paste-up artist is able to complete their work at home or in the studio, slapping it up on a wall or surface in public space quickly and covertly. The Velvet Bandit usually undertakes this work in an unauthorized manner and she makes efforts to maintain her anonymity. Whether they are painted over, removed or simply degrade over time, paste-ups always have a limited lifespan, encouraging artists working in this medium to create images that speak very directly to the moment.

Figure 19.1 The Velvet Bandit, ‘Take Me To Your Leader’, photographed 6 April 2020

Photo © The Velvet Bandit, 2023, all rights reserved

‘Take Me To Your Leader’ was photographed by the artist on 6 April 2020 in Santa Rosa, California, and shared by way of the artist’s Instagram account. It is quite typical for The Velvet Bandit to share her work by way of social media in order to gain wider visibility. This is particularly important because these small pieces, adhered to a surface using wheat paste, are quite ephemeral. The coronavirus is depicted as a spiky blue and turquoise sphere, reminiscent of a bouncy ball. A bright pink label on the sphere reads ‘Take Me To Your Leader’. This piece is a play on the popular science fiction troupe in which an alien life form arrives on earth, presumably with hostile intentions, and asks to be taken to the leader. In science-fiction films, the leader is generally depicted as inept and unable to solve the crisis, leaving it to local heroes to save the planet. The cartoon-like rendition of the virus and playful reference to popular alien movies and cartoons makes this paste-up seem lighthearted and fun but it reflects deep frustrations with the country’s leadership in spring 2020. In this case, The Velvet Bandit uses a seemingly playful paste-up to express profound disagreement with President Trump and his handling of a national crisis. Widespread lockdown policies, which were in place in many places throughout the United States at the time this piece was documented, had a disproportionate impact on working-class people. Those in power, including Donald Trump, were well insulated from the virus and protected from the negative consequences of the shutdown, while people working in industries such as hospitality and healthcare faced the realities of job loss and lack of safety. This piece reflects a very real if malicious shared hope that Donald Trump would himself be forced to confront the virus in a manner that was up close and personal while also expressing doubt that he, as a ‘leader’, could resolve the crisis in an effective manner.

Figure 19.2 The Velvet Bandit, ‘Bring Back Ebola’, photographed 11 May 2020

Photo © The Velvet Bandit, 2023, all rights reserved

‘Bring Back Ebola’, a bright red popsicle set against a vivid blue dumpster, appears to be a light and playful reminder of a refreshing childhood treat. However, this seemingly simple image reflects on more complicated ideas about epidemics and pandemics, the containment of disease and how we face realities that were previously unthinkable. Looking closer at the popsicle, we can see text reading ‘Bring Back Ebola’, referencing the Ebola haemorrhagic fever outbreak that first emerged in late 2013 in Guinea and led to widespread transmission in Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone in 2014-2016. Ultimately seven other countries were affected, including Italy, Spain, the United Kingdom and the United States, leading to concerns that Ebola would develop into a global pandemic. The virus was successfully contained, though, due to the coordination of international public health organizations. In 2016, the World Health Organization (WHO) lifted PHEIC (Public Health Emergency of International Concern) status for Ebola (Centers for Disease Control 2019). In contrast, when the ‘Bring Back Ebola’ popsicle wheat paste was documented in Santa Rosa, California, on 11 May 2020, the World Health Organization had declared Covid-19 a pandemic (this happened on 11 March 2020) and on 2 May 2020, WHO had renewed its emergency declaration. Lockdowns were widespread and the US unemployment rate had just hit its worst point since the Great Depression. Many people wondered if an end was in sight for the pandemic. The death toll was quite high in the United States at this point, hitting one hundred thousand deaths less than a week after this piece was documented. In the United States, people were confused by seemingly conflicting messages that came from the Centers for Disease Control and federal, state and local governments. In retrospect, the viewer of this piece might feel a strange nostalgia for the Ebola outbreak: a time when there was much fear of a pandemic but a sense that international organizations were working cooperatively to resolve an issue of global concern. In reality, the 2014-2016 Ebola outbreak had very little actual impact on life in the United States and, while there were some travel restrictions, it necessitated no changes to daily life. Ultimately, the fatality rate with Ebola was much higher in each infected individual but the virus was more easily contained when compared to Covid-19.

Figure 19.3 The Velvet Bandit, ‘Smile More’, photographed 10 May 2020

Photo © The Velvet Bandit, 2023, all rights reserved

‘Smile More’, documented on 10 May 2020 in Santa Rosa, California, uses a children’s book character to reflect on the issue of street harassment. A child would easily recognize this figure as a play on the Disney illustration of Alice in Wonderland. Here Alice wears a face mask with text reading ‘Smile More.’ Men randomly commanding women to smile is a common form of street harassment in the United States and it sends the message that a woman has an obligation to arrange her face in a manner that conforms to a man’s desires. ‘Stop Telling Women to Smile’ was a nationwide street art project beginning in 2012 by artist Tatyana Fazlalizadeh. Fazlalizadeh’s portraits of real women were juxtaposed with text calling attention to street harassment (Fazlalizadeh n.d.). Whereas Fazlalizadeh’s series focused on imposing portraits of real women juxtaposed with their own words, The Velvet Bandit takes a more playful approach by using Alice as a stand-in for the victim of harassment. At a time when the use of face coverings was widespread or even mandatory, some women felt that a mask could serve as a shield and offer a sense of privacy from strangers in the street (Maloy 2021). Others lamented the fact that the mask made it more difficult to use facial expressions to ward off harassers (Nadège 2020). In this way, a playful rendition of Alice in Wonderland serves as a critique of the patriarchy.

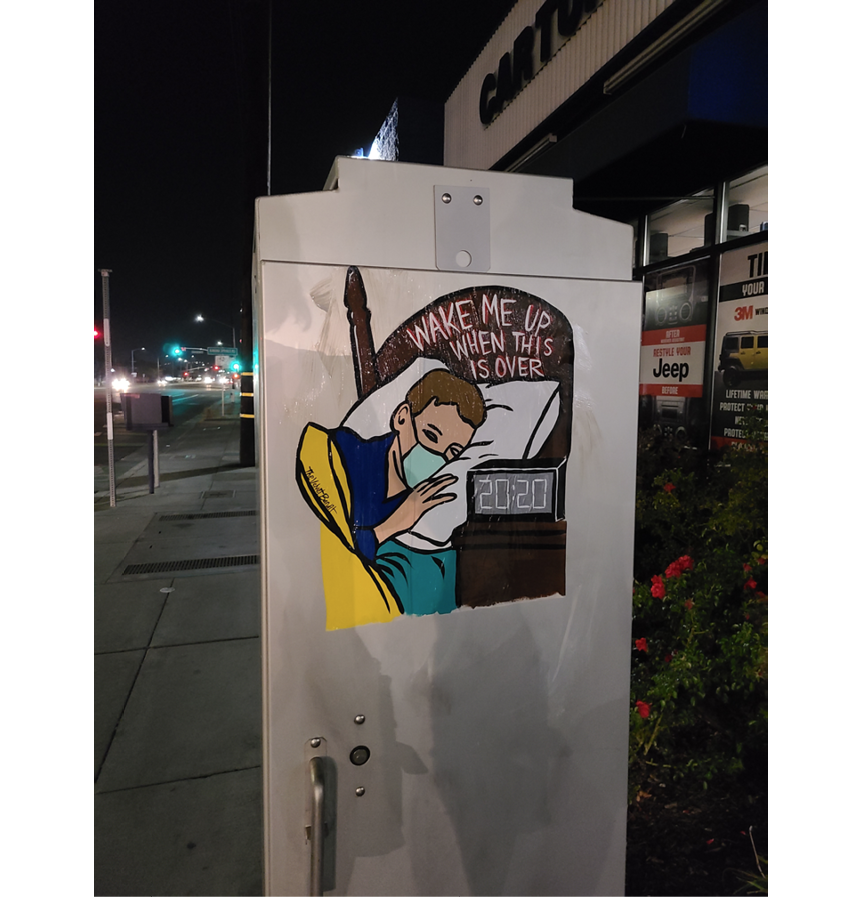

Figure 19.4 The Velvet Bandit, ‘Wake Me Up When It’s Over’, photographed 17 December 2020

Photo © The Velvet Bandit, 2023, all rights reserved

‘Wake Me Up When It’s Over’ was documented in San Francisco on 17 December 2020. This wheat paste shows a child tucked in and sleeping peacefully. He is covered by a bright yellow blanket and he wears blue plaid pyjamas and a turquoise medical mask. Wearing a medical mask while sleeping alone in bed would clearly be unnecessary so we can surmise that the artist chose to include the face covering in order to emphasize Covid-19 as the subject of the work. The time on the alarm clock reads 2020 and text on the headboard reads ‘Wake Me Up When It’s Over’. The text playfully reflects on our ironically naïve expectation that the passing of a milestone, the turning of a new year, might bring with it new realities and that the negative events and experiences of 2020 could be somehow partitioned off and contained. There was indeed a sense of hopefulness in December 2020 as vaccines were beginning to be available to selected populations, and the United States was looking ahead to the inauguration of President Joe Biden and the hope of a new national response to the virus in January 2021, making this a playful reflection on the mood during the period after the presidential election and the inauguration.

Figure 19.5 The Velvet Bandit, ‘Orange Ya Glad I’m Not Covid 19’, photographed 4 March 2021

Photo © The Velvet Bandit, 2023, all rights reserved

‘Orange Ya Glad I’m Not Covid-19’ was documented on 4 March 2021, several weeks after Donald Trump’s departure from the White House. Still, the spherical orange with a single jaunty leaf shooting off to the side serves as a stand-in for a portrait of President Trump, who was often mocked for the orange tone to his skin and his dramatic swoop of hair. While playfully referencing the punchline of a familiar ‘Knock knock’ joke, this piece indicates how deeply politicized the pandemic became in the United States, as Donald Trump frequently expressed opinions, gave advice and supported policies that contradicted scientific facts.

SudaLove

Assil Diab, working in the streets under the name SudaLove, is a Sudanese street artist educated in graphic design at Virginia Commonwealth University and based in Doha, Qatar. (Muzawazi). She is known as the first female graffiti artist in Sudan and Qatar (Muzawazi 2017). In 2019 SudaLove undertook an important series of works memorializing political martyrs in Khartoum, Sudan, where she and her collaborators took tremendous personal risks to paint murals that honoured ordinary citizens who were killed by the state during the revolution. During the early months of the pandemic, SudaLove returned to Khartoum to spray-paint a series of murals that use large, brightly coloured, engaging imagery to address the public health crisis that Covid-19 presented. Sudan reported its first confirmed case of Covid on 13 March, 2020. The infected patient had traveled to the United Arab Emirates and died on 12 March 2020 in Khartoum. SudaLove’s murals relating to Covid-19 were produced in March 2020.

Figure 19.6 SudaLove with Khalid al Baih, ‘Covid Explosion’, photographed March 2020

Photo © Assil Diab/SudaLove, 2023, all rights reserved

The ‘Covid Explosion’ was a collaboration with political cartoonist Khalid al Baih. During the early part of the pandemic, many artists sought to visualize the coronavirus, transforming the invisible into something more tangible. As it is spread through invisible droplets, it is impossible to actually see the coronavirus and therefore it is perhaps easy to ignore the reality of its presence. Borrowing from an image by Khalid al Baih, SudaLove depicted a laboratory flask spewing out a green spherical form with the virus’s crown-like protein spikes. Tiny green dots surrounding the flask and virus reference its spread through miniscule droplets. The image is large, colourful and engaging, and yet it also does the important work of visualizing and therefore making real the presence of Covid-19.

In an interview with Urban Art Mapping in January 2022, Diab spoke of her role as an artist educating people about public health concerns:

There was a mandatory lockdown so I had to have permission to carry out these murals, and when I used to go out and I used to see people walking, there were lots of homeless people in the streets. They would come up close and try to touch my spray paint—and I would say ‘no, this is a mural about the coronavirus and we have to stay away from each other’—but some of them didn’t even know what the coronavirus is. You could tell that people had no idea what was going on and when you explained it, they didn’t really care. And it is not that people don’t care about their health, it’s just that people went through so much before that, the pandemic was the least of their problems at that time. (Diab 2022)

To this end, SudaLove painted several murals using playful imagery to promote the proper use of face coverings as well as mandated stay-at-home orders.

Figure 19.7 SudaLove, ‘Stay At Home’, photographed March 2020

Photo © Assil Diab/SudaLove, 2023, all rights reserved

One example is a portrait of a man in a white hoodie with pink sunglasses. He wears a surgical face mask. Text in Arabic reads ‘Stay At Home’ and small renditions of the spikey coronavirus surround the text.

Figure 19.8 SudaLove, ‘Face Masks’, photographed March 2020

Photo © Assil Diab/SudaLove, 2023, all rights reserved

In another mural a crowd of individuals, all wearing different styles of head coverings and clothing, is created through simple black outlines. The figures are packed closely together and they are all shown in profile, as if they are engaging with each other. Each figure wears a blue surgical face mask. Diab stated in her January 2022 interview that it was rare to actually see people wearing face coverings in the street and she meant for the mural to normalize their use (Diab 2022).

Figure 19.9 SudaLove, ‘Face Masks/Stay At Home’, photographed March 2020

Photo © Assil Diab/SudaLove, 2023, all rights reserved

The third and most complex of these murals depicts four large, highly detailed portraits of individuals wearing different styles of head coverings. Each figure is wearing a surgical face mask with text reading ‘stay at home’ written in a different language. SudaLove explained:

You’re tackling issues from a very national point which is a Sudanese point of view. We have over three hundred tribes in Sudan with different religions and dialects, so even when you want to get married, people usually ask what tribe you are from. […] So the idea was to tackle the health issue and bring it from a very personal point of view, to talk about tribes. So that’s why I put these different Sudanese people from different tribes all on the same wall, all saying ‘stay at home’ in their own dialect. […] This is a time when we need to come together to fight this one issue regardless of your tribe, your background, you are gonna get the virus. (Diab 2022)

Figure 19.10 SudaLove, ‘Omar al-Bashir Virus’, photographed March 2020

Photo © Assil Diab/SudaLove, 2023, all rights reserved

Finally, most overtly political of SudaLove’s Covid-19 works is a depiction of deposed head of state Omar al-Bashir with a green face and two horns emerging from his head, transforming him into a spikey coronavirus. Widespread protests against al-Bashir began in December 2018 and he was ousted by a military coup d’état in April 2019. At the time this work was painted, al-Bashir was imprisoned and preparing to face trial for corruption charges. While the image appears playful and cartoon-like, it addressed the intertwined nature of Covid-19 and politics, specifically the need to find unity during a politically divisive moment. About this work, SudaLove stated:

Now we have this pandemic right after we won this war, and now we have something else we’ve gotta take care of, and that’s another issue in Sudan as well with our medical organization, just how our healthcare in Sudan is not that great. So the idea was to remind people that we got over the biggest disease that we had, which was Omar Al-Bashir, and we need to come together at this time again to fight this new health war, which is the coronavirus. To paint Omar Al-Bashir in daylight in a public place was just baffling to me because you couldn’t write or say anything in public that opposed him [before the revolution]. (Diab 2022)

As the artist indicates, this simple, cartoon-like image embodies complex ideas about ongoing struggles in post-revolutionary era, made all the more complicated by the pandemic.

Seen together and in the context of the global pandemic, the work of SudaLove and The Velvet Bandit demonstrates that playful imagery can provide an avenue for responding to the pandemic in a manner that is quickly accessible to the public. In contrast to art created in private spaces, art in the streets allowed for the shared processing of the complex shared trauma of isolation, embracing playfulness while also recognizing a sense of loss and disbelief, as well as the justified feelings of anger and confusion that shaped experiences around the world.

Works Cited

Avramidis, Konstantinos, and Myrto Tsilimpounidi. 2017. Graffiti and Street Art: Reading, Writing and Representing the City (Abingdon: Routledge)

Awad, Sarah H. and Brady Wagoner (ed.). 2017. Street Art of Resistance (Cham, Switzerland: Springer International; Palgrave Macmillan)

Bloch, Stefano. 2020. ‘COVID Graffiti’, Crime, Media, Culture, 17: 27-35, https://doi.org/10.1177/17416590209462

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2019. ‘2014-2016 Ebola Outbreak in West Africa’, https://www.cdc.gov/vhf/ebola/history/2014-2016-outbreak/index.html

Diab, Assil. 2022. Interview with Urban Art Mapping, 27 January

Fazlalizadeh, Tatyana. n.d. ‘Stop Telling Women to Smile’, http://www.tlynnfaz.com/Stop-Telling-Women-to-Smile

Maloy, Ashley Fetters. 2021. ‘Masks Are Off—Which Means Men Will Start Telling Women to “Smile!” Again’, Washington Post, 22 May, https://www.washingtonpost.com/lifestyle/2021/05/22/men-telling-women-smile/

Muzawazi, Rumbie. 2017. ‘Assil Diab: Being an Arab Muslim Female Painting in the Streets Is Not Always Applauded’, She.Leads.Africa, 11 September, https://sheleadsafrica.org/tag/sudalove/

Nadège. 2020. ‘We Need to Talk about Street Harassment while Wearing Masks’, Medium, 16 July, https://medium.com/fearless-she-wrote/we-need-to-talk-about-street-harassment-while-wearing-masks-58fda4bef657

Urban Art Mapping. 2020. ‘Covid-19 Street Art Archive’, https://covid19streetart.omeka.net

Velvet Bandit, The. 2022. Interview with Urban Art Mapping, 27 January