4. ‘Let Them Play’:Exploring Class, the Play Divide and the Impact of Covid-19 in the Republic of Ireland

© 2023, Maria O’Dwyer et al., CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0326.04

Play and Ireland: An Overview

Bruner’s work in the 1970s oriented play as the basis for the ‘flexibility of thought’ which underpins the immense problem-solving abilities and creativity of humans (1972). In more simple terms, the long period of biological immaturity in humans provides us with ample opportunities to practise and develop our play skills. These play skills then support mental, physical, socio-emotional, cognitive and social development. Play is inarguably a multi-faceted phenomenon. While it is a feature of all societies, its prevalence and forms vary across them, as the very nature of childhood itself and the value of play are culturally and environmentally shaped. Indeed, play itself has been described as ‘pedagogic culture’ (Arnott and Duncan 2019), created by the interplay between the contextual cues, such as space, interpersonal collaborations and materials, that frame young children’s creative play.

Running parallel to these macro-developments in the conceptualisation of play and its function, there is a concern internationally that children’s free play has decreased, especially for middle-class, female, young and ethnic minority children (Holloway and Pimlott-Wilson 2014). Play has become individualized and ‘pedagogised’, that is, play has been configured as a means ‘to limit the risks of certain biographies and to offer children and adolescents the best possible start in life’ (Frahsa and Thiel 2020: 2). This has given rise to a decline in free play and outdoor play which are packaged as more risky (Carver, Timperio and Crawford 2008, Timperio et al. 2004; Powell, Ambardekar and Sheehan 2005; Veitch et al. 2006; Farley et al. 2007). Play has also been medicalized, e.g. as an antidote to a childhood obesity pandemic (Demetriou et al. 2019; Tremblay et al. 2015; Australian Government Department of Health 2014).

The ludic landscape of Ireland has also been shaped by related societal trends. Opportunities for and access to play have changed significantly in Ireland over the last two decades, with a notable reduction in opportunities for free, unstructured play. A primary driver of the development of the Irish early childhood education and care (ECEC) sector, through the highs of the Celtic Tiger (economic boom) to the lows of the pursuant recession, has been labour activation. While ECEC provision is delivered through a variety of play-based curricula, the nature of care means that much of it is adult-led and children are grouped according to age, resulting in less exposure to mixed-age peer play. This period has also been characterized by an increasing desire by public bodies to avoid litigation by risk-assessing playgrounds and public parks (i.e. the preference for soft rubber ‘flooring’ over natural woodchips, etc.). The rising role of technology and its integration into toy making and marketing offer what Gosso and Almeida Carvalho describe as ‘an increasing variety of sedentary and often individualised and highly-structured toys and games which allow little space for children’s creativity in the exploration and collective construction of play objects and materials’ (2013: 6). This has led to what could be described as a ‘sanitization’ of play, whereby our desire to nurture and support children in safe environments has resulted in more structured and less risky play. There exist, therefore, competing national discourses of safety and protection versus play and autonomy in the structuring of children’s everyday lives in Ireland (Kernan and Devine 2010).

This trend of play becoming more structured is evident in Ireland as elsewhere and it has been related to the hurried child syndrome (Elkind 1981; Frost 2011). Smyth (2016) studied young children in Ireland and their involvement in creative play (such as painting, drawing and playing make-believe games) as well as the more traditional cultural pursuits of reading and attending educational or cultural events with their parents. Even at the early age of five, gender and social background differences are apparent in children’s exposure to these activities. Children from highly educated or middle-class families, for example, watch much less television than their peers regardless of child gender (Smyth 2016).

American, US and UK literature acknowledges that ‘class gaps in structured activity participation’ exist (Bennett, Lutz, and Jayaram 2012: 133), revealing the existence of different ‘parental logics’ by middle- and lower-class parents, with middle-class parents seeing extra-curricular activities, including play, as vehicles for creating and securing social status (e.g. Chin and Phillips 2004; Bennett 2012; Laureau 2003; Vincent and Ball 2007; Aurini, Missaghian and Milian 2020). Despite this, there has been scant engagement with this theory and associated research in Irish childhood studies. Little has been written about how child play is mediated by social class in Ireland. This book chapter takes the opportunity to reflect upon this under-researched topic to present an appraisal of how class insinuates and configures Irish children’s play. The disruptive impact that Covid-19 has had on children’s opportunity for structured play, as revealed in the Growing Up in Ireland study, will form the basis of this chapter, acting as a timely case study into the play divide in Ireland. The research discussed here represents the preliminary findings of our study and are part of an ongoing piece of work into the play divide in Ireland.

The Play Divide in Ireland

There is a growing body of research that children’s play or, more specifically, what parents allow their children to do as playful activity, is heavily inscribed with class aspirations and significations. For instance, it has been found that middle-class parents tend to enrol their young children in extracurricular creative and sporting activities more readily than working-class parents. The reason for this is not merely a question of financial means; middle-class parents look upon such activities as a way of ‘distinguishing’ their child for the middle class (e.g. Vincent and Ball 2007). As active promoters of their children’s social capital, middle-class parents have identified play and structured activities as a means of securing social mobility and status for their children. This act of ‘concerted cultivation’ (Lareau 2000, 2003) distinguished the ‘parenting logic’ of middle-class parents from the ‘natural’ parenting approach of working-class parents, i.e., letting the children find their own way in the world (Lareau 2000, 2003; Chin and Phillips 2004: 186).

Before moving on, it is important to discuss what we mean by social class, in particular the nature of this categorization in the Irish context. Many commentators have debated the political exceptionalism of Ireland being one of the few countries in Western Europe that did not experience an industrial revolution. The ensuing absence of an industrial class living in densely populated, urban cities and the continued prevalence of agricultural production contributed to the development of a political culture based on the local community rather than class-based struggle (e.g. O’Carroll 1987). Confirmation that notions of ‘class’ were articulated differently in Irish society from the 1930s to 1990s can be found in the oral history records from that time. There, the word ‘class’ was rarely used by its participants. That was not to say that their oral histories were devoid of an awareness of social difference and status. Rather, what followed was a nuanced understanding of class mediated by place in which rural participants discussed social status in terms of land ownership (big/small farmers) and urban participants discussed social difference in terms of employment type (Cronin 2007: 34-35). Other signifiers of class were diet/food, e.g. Sunday dinners (Cronin 2007: 37). Even though Irish society has undergone a process of ‘accelerated modernization’ since the mid-1990s—successive cycles of economic boom (Celtic Tiger economy 1994-2007) and bust (recession 2008-) and changing demographic trends based on inward and outward migration—the growing divide between rural and urban areas, lower fertility rates and the rise of working mothers and the associated issue of affordable childcare (e.g. Power et al. 2012; Cullen and Murphy 2020; Coulter and Arqueros-Fernandez 2020), and rurality and place still rank as important signifiers of class.

It is worth highlighting that a ‘play divide’ has emerged consistently in Ireland for the last twenty to thirty years. While numerous studies (Stirrup, Evans, and Davies 2016) consider the reproduction of social class and cultural hierarchies in early childhood care and education settings, little research has focused on play as an expression of class demarcation or divide. In Ireland, this is perhaps most perceptible in outdoor play practices and norms. In 2010, How Are Our Kids, a large-scale study, explored the needs and experiences of children and families in Limerick city, with a particular emphasis on Regeneration Communities, that is, the most deprived areas of the city. The description of the lives of children and families paints a picture of a poorer quality of life, poor experiences of childhood and worse outcomes across a wide range of indicators of child well-being between children living in the most deprived neighbourhoods of Limerick city. While crime, anti-social behaviour and community safety were issues in the Regeneration Communities, parents reported concerns for the impact of this on older children and teenagers. Younger children, however, appear to have benefitted from greater freedom in these neighbourhoods. Strong community networks, intergenerational living (availability and proximity of extended family) and the more traditional ‘it takes a village’ approach to child-rearing influenced this freedom. The findings indicate that in communities experiencing much higher than average levels of socio-economic disadvantage and relative deprivation, children engaged more in outdoor play. It could be argued that there is a traditional element to these outdoor play opportunities, whereby children are afforded responsibility at an earlier age, older siblings look after younger ones and micro mobility (i.e. the use of scooters, skateboards, quad bikes and, in some cases, horses) is more normalized. This is, essentially, the kind of unstructured outdoor play that would have typified Ireland in the 1980s, where children played outside independently, daily and for significant periods of time. This stands in contrast to the play experiences of young children in middle-class areas where scheduled ‘play dates’, extra-curricular activities and paid childcare are more common. Lee et al. (2021) contend that individual, parental, and proximal physical (home) and social environments appear to play a role in children’s outdoor play and time, along with ecological factors such as seasonality, rurality, etc. The study in Limerick city would indicate that is very much the case.

The Impact of a Global Pandemic on Play

The World Health Organization officially declared that the world was in the grasp of a coronavirus (Covid-19) pandemic on 11 March 2020. In the following two years in European and longer elsewhere, all social, health and economic systems have been trying to respond to unprecedented demands and challenges. Anthropologists call such an event a ‘liminal moment in which a given order that is considered normal or desired is dissolved, breaks down, and is affected by a decomposition or unbalance that needs to be restored’ (Visacovky 2017: 7). As ‘the tranny of the urgent’ (Davis and Bennett 2016) crisis management mode took over, world leaders and global systems tried to make sense of and adjust to an unprecedented threat to global health and well-being. This period of profound disruption took many forms. These include, but are not limited to, a deceleration of everyday life, the shrinkage of social spaces, the collapsing of work and domestic spaces, the closure of schools and businesses, and the accelerated digitalization of society (Fuchs 2020, Devine et al. 2020, OECD 2020). While many were struggling to stand still amidst the whirlwind of change, Covid-19 also provided the sober reminder of how stratified society is with pre-existing social and health inequalities gaining added poignancy and severity (e.g. Public Health England 2020; Raharja, Tamara and Kolt 2020; Sze et al. 2020). The psycho-social and educational impact of children living in a pandemic also came under scrutiny. How, and in what way, would children’s social, emotional and educational development be affected by living through a pandemic? Early Irish evidence suggested the widening of educational gaps (e.g. Darmody 2021; Doyle 2020; Mohan et al. 2020).

For researchers in the Republic of Ireland this question took on added poignancy because the nation enacted one of the harshest lockdown responses compared with other countries (Hale et al. 2021). All Irish schools were closed for 141 school days, from 13 March to 30 June 2020 which marked the end of the academic year. This was the longest school closure period in the history of the state as well as in comparison with other comparative OECD countries (Richardson et al. 2020). In all, approximately one million children and young people (Central Statistics Office 2020) (or 1 in 5 of the Irish population) were directly affected by this pandemic response. Unsurprisingly, there has been a raft of studies exploring the educational impact of Covid-19 on Irish school-aged children (e.g. Chzhen et al. 2022; Flynn et al. 2021). These Irish studies confirm trends being witnessed across other developed countries (Rao and Fisher 2021), namely, that the sudden shift to remote/distance learning confirmed long-standing educational inequalities, regarding access to digital technologies (Armitage and Nellums 2020; Chzhen et al. 2022: 2) and families’ capacity/ability to support their child’s learning (Doyle 2020; Chzhen et al. 2022: 2). While digital supports were available to both primary and secondary level schools to help offset these digital disparities, such as in the form of loaning schemes for laptops to disadvantaged families, available research reveals the absence of a standardized approach to how schools administered and allocated these emergency digital resources (Brown 2021; Burke and Dempsey 2020; Cullinan et al. 2021). Such educational disruption was also recognized as impacting on children’s well-being and learning resulting in feelings of social isolation and loneliness (Flynn et al. 2021).

While the play divide received little attention, there has been a growth in the study of the digital divide. Some authors contend that digital technology is displacing other, more wholesome activities, such as the intellectually or physically beneficial pastimes of reading or playing outdoors in certain social groups. Proponents of this school of thought associate increased time with digital technology with the increased sedentarism of twenty-first century childhood. For others, the content that young people find online, such as violence-infused gaming or online predators masquerading as children, is the cause for concern (Gentile et al. 2017). Regardless of whether you support the displacement theory or content theory regarding digital media and children, the fact that we are living in a digitalized, networked society is inescapable. Children, parents, policy makers and legislative structures all broker affirmative and transformative ways of working with digital technology.

The Republic of Ireland, like other developed countries, has taken a keen interest in developing evidence-based, research-informed policies to safeguard its young citizens against the excesses of digital technology (e.g. O’Neill and Dinh 2013; Government of Ireland 2018; Children’s Research Network 2020). Research confirms that the pattern of digital usage among young children in Ireland is largely similar to their European counterparts (O’Neill, Grehan and Olaffson 2011; O’Neill and Dinh 2015, Smahel et al. 2020). In 2010, Irish children spent one hour in average online (O’Neill and Dinh 2015), this rose to 2.1 hours a day during the week and 3.4 hours a day at weekends by 2020 (National Advisory Council for Online Safety 2021: 22). The smartphone is the most popular social media device. In 2014, thirty-five percent of children used a smartphone (O’Neill and Dinh 2015), this rose to seventy percent in 2020 (National Advisory Council for Online Safety 2021: 9, 10). Children as young as eight are using a smartphone, with the majority between the ages of 11 and 12 (Cybersafe Kids 2020, 2021, 2022). Irish young children are regular and at times heavy users of digital technology, as indicated by the increase in screen time over the past decade (e.g. Bohnert and Garcia 2020), with online entertainment and social networking as the two main reasons why young children used the internet (O’Neil and Dinh 2015).

The top five online activities of Irish children are as follows: watching video clips (58%), listening to music online (55%), communicating with family and friends (53%), playing online games (40%), using social networking (38%) (National Advisory Council for Online Safety 2021:24). Using the internet for school purposes was lower down their priorities (34%) (National Advisory Council for Online Safety 2021: 24). When disaggregated according to age and gender a distinct pattern emerges. Generally, social internet usage increases with age, for both genders. However, certain activities reveal a marked gendered effect. Thirteen- to seventeen-year-old girls are more likely to use the internet for schoolwork (51% compared to 35%), social networking (62% compared with 51%) and communicating with family and friends (70% compared with 66%), compared to boys. Boys more likely to use the internet to watch video clips (73% compared to 61%) and game than girls (56% compared to 34%) (National Advisory Council for Online Safety 2021: 24). This trend represents a pattern is also found among the nine- to twelve-year age groups.

At first glance, this body of work promotes a conventional and easily comparable view of Irish children’s engagement with digital technology vis-à-vis other EU countries. However, when we explore Irish play data more closely we find an alternative and more interesting situation. Despite the paucity of research into children’s play in Ireland (Rowicki and McGovern 2018), some studies have touched on a more complex pattern involving class, gender and geographical factors.

A 2007 school survey and focus group study involving 292 children aged between the ages of four and twelve years from ten primary schools across Ireland found that outdoor active play, like football, was the most popular form of social play (Downey, Hayes and O’Neill 2007). Interestingly seventy percent of this category were male and from a rural background (Downey, Hayes and O’Neill 2007: 15). This was followed by chasing and then digital technology/games (Downey, Hayes, and O’Neill 2007: 15). Again, it was more likely for males from a rural background (Downey, Hayes and O’Neill 2007: 15). Digital technology came first in the options for solo play (Downey, Hayes, and O’Neill 2007: 15). Again this play preference was more commonly expressed by boys than girls, and those from a rural background (Downey, Hayes and O’Neill 2007: 15). Fifty percent of children surveyed played computer games, whereas twenty-five percent cited readings as a favoured pastime (Downey, Hayes, and O’Neill 2007: 15)

Rowicki and McGovern’s analysis (2018) of time use in Growing Up in Ireland employing diary data from 2007-2008 when the children were aged nine, and from wave 2 of the study when they were aged thirteen, offers a more contemporary glimpse into Irish childhood. Girls at age nine spent fifty minutes playing sports each day, regardless of socio-economic group. This fell for all by age thirteen but especially for those from lower socio-economic groups (twelve minutes versus twenty-nine minutes). All girls spend more time on media from nine to thirteen years of age. At age thirteen, children from lower SES spent more time (108 minutes) with digital technology compared with higher socio-economic status (86 minutes). The situation was reversed with unstructured play with girls from working-class backgrounds recording an increase in unstructured play time from age nine to thirteen (fifteen minutes per day) compared with a decrease of two and ten minutes for girls from higher socio-economic groups. Overall, girls and boys from lower socio-economic groups spend less time in sport activities and more time using digital technology at age thirteen.

Helster conceptualizes these socio-digital inequalities as ‘systematic differences between individuals from different backgrounds in the opportunities and abilities to translate digital engagement into benefits and avoid the harm’ (2021: 34). Recent research in Ireland has compared two cohorts of children growing up in the ‘digital age’ using data from the Growing Up in Ireland study. In 2017-2018, nine-year-old children spent more time on digital devices and social media, while in 2007-2008, nine-year-old children spent more time watching TV and adopted less diversified forms of media engagement (Bohnert and Gracia 2021). The study found that the effects of digital use on socio-emotional well-being were quite similar by gender and socio-economic group in both cohorts.

The digital divide in classroom technology use has received much attention given the school-level inequalities witnessed during Covid-19. Yet little work has focused on social class and the daily lives of children during the pandemic. The next section will outline differences in the lives of children as reported by the children themselves during Covid-19.

Data

The Growing Up in Ireland (GUI) study started in 2006 and follows the progress of two groups of children: around eight thousand nine-year-olds (Cohort ’98) and ten thousand nine-month-olds (Cohort ’08). The members of Cohort ’98 are now aged about twenty-four years and those of Cohort ’08 are around thirteen years old. The following results refer to the experiences of the ’08 cohort, who filled in a special Covid-19 survey in December 2020 when they were aged twelve. The survey’s timing coincided with the relaxation of what were the most severe (Level 5) restrictions after the second wave of Covid-19 in the autumn. The survey was brief, taking about ten minutes to complete online, and focused on a relatively small number of key experiences and outcomes. As with all online surveys, the response rate was lower than face-to-face interviews, so that 3901 surveys were completed by parents and 3301 by twelve-year-olds.

Changes in Free Time

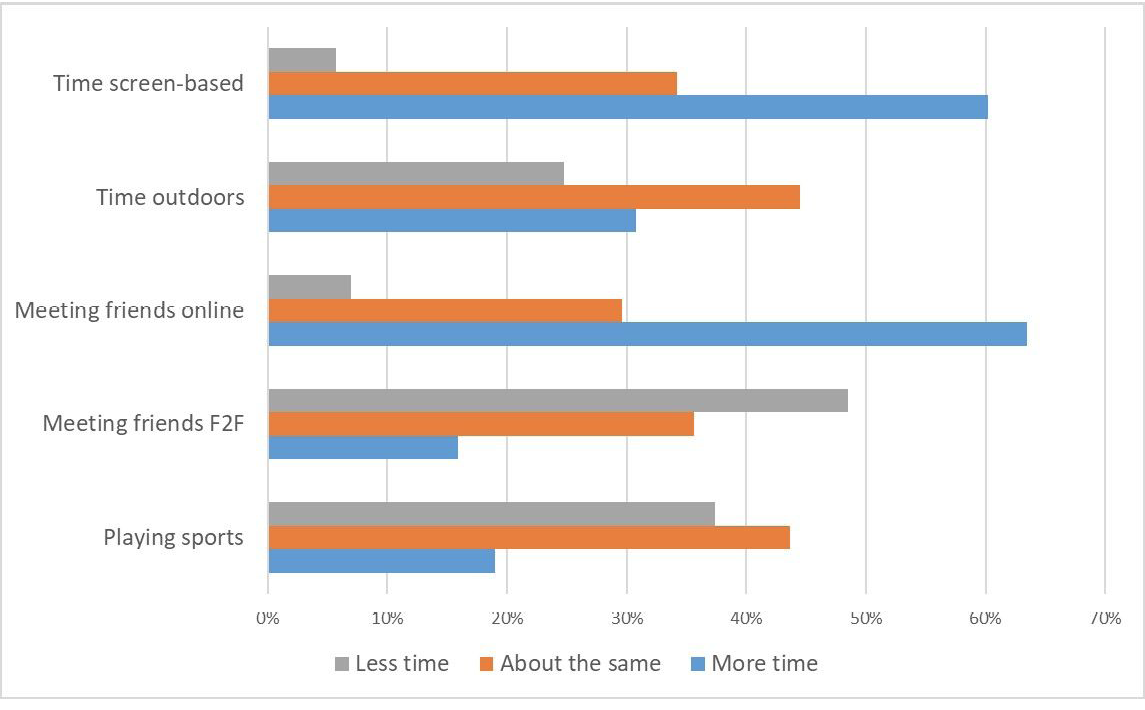

As many facilities were closed, families spent more time at home together. Many parents of twelve-year-olds reported enjoying time with their family (sixty-three percent said this was ‘always true’) and doing more activities together (forty-eight percent ‘always true’). But they also had less time to themselves (thirty-one percent ‘always true’). The twelve-year-olds were asked to compare their lifestyles at the time of the survey (December 2020) to the period just before the pandemic struck (March 2020). Figure 4.1 shows the percentages who described doing particular activities ‘more’ or ‘less’ often than before. According to the children, there are substantial changes in the amount of time they spent on different types of activities as a result of the pandemic and associated restrictions.

Figure 4.1 Child reports on differences in time spent on classes of activities in December 2020 compared with March 2020, before the pandemic (data source: Infant ’08 Cohort, wave 5 and Covid survey, Growing Up in Ireland study)

In December 2020, therefore, most twelve-year-olds reported increases in time spent with family, on informal screen activities and talking to friends online or by phone and less time with friends face-to-face and playing sports (see Figure 4.1). There are, however, some important differences in these activities by child gender and family social class. In terms of gender, girls were significantly more likely to report spending more time meeting up with friends online or over the phone (sixty-nine percent compared to fifty-nine percent of boys at p<0.00). The nature of female relationships has often been characterized as more about sharing and intimate confiding than the more instrumental approach taken in male friendships (see, for example, O’Connor 1992).

In terms of social class differences, there was an under-representation of families from lone parent, poor and working-class backgrounds in this online Covid-19 survey (see Kelly et al. 2021). This means that the results do not represent the population in terms of these characteristics. Despite this, some class divides are evident in terms of the time children reported spending outdoors and online. Children from families where occupational/employment information was missing or unavailable (due to parents not being employed) were more likely to report spending less time outdoors in December 2020 compared to March of that year. In addition, children from unskilled manual backgrounds were most likely to report spending less time online (note the small n=20). In addition, as further evidence of Lareau’s conceptions of concerted cultivation, there were significant class differences in taking part in organized cultural activities, like music and drama classes (chi2=24.6919 P=0.038). Caution is however advised in interpreting these figures, given the small numbers in certain class categories.

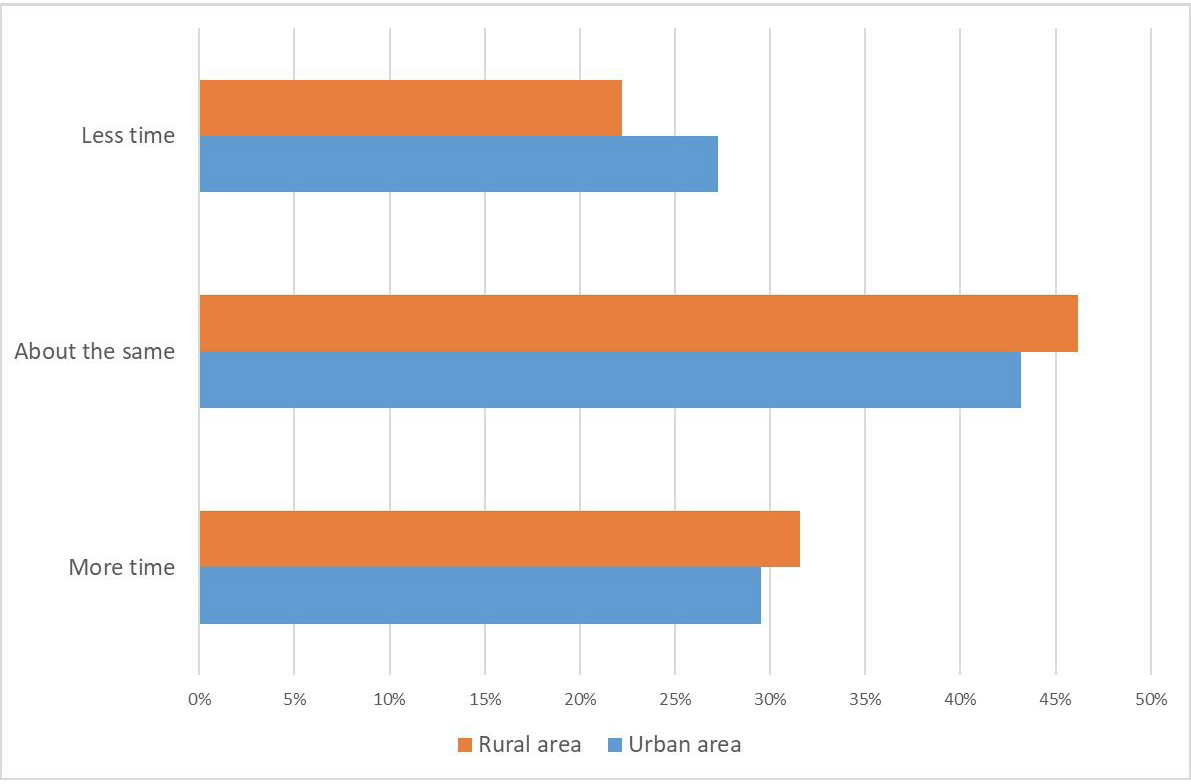

A more fruitful way to highlight the impact of the pandemic on children’s free time is to look at differences between rural and urban Ireland. Children and childhood is rural Ireland has been a topic of study for some time (Tovey 1992; Curtin and Varley 1994; Devine 2008; Gray 2014). Much of the work drew on the role of children in the stem-family system in the first half of the twentieth century and then later, their role in farming families. Little attention has focused on the differences in experience of childhood in rural versus urban contexts in current times. This is especially important in the context of the pandemic where the availability of high-speed broadband and public transport was limited in many rural areas.

In the Growing Up in Ireland study, there was a clear divide in how the pandemic impacted children based on their location. In December 2020, children in urban areas were significantly more likely to report that they were spending less time outdoors compared to children growing up in rural areas of Ireland (see Figure 4.2). Compared to children living in urban areas, children growing up in rural areas were more likely to report spending the same or more time outdoors in December 2020 compared to March of that year. We do not have information in the study on what the children were doing outdoors, but we do have information of the time spent online. There was no rural/urban divide in the time children reported to spend online. There were, however, significant differences in who the children reported spending time with. Children in rural areas were more likely to report spending more time with family compared to children in urban areas (chi2 = 24.2303 P= 0.000), whereas children in urban areas were more likely to report seeing their friends face-to-face. This may simply be related to the closer proximity to friends in urban areas. This analysis does raise more questions than answers and allows us the first glimpse into how the lives of children have changed during the pandemic, as reported by the children themselves.

Figure 4.2 Children’s comparison of time spent outdoors by region in December 2020 compared with March 2020, before the pandemic (data source: Infant ’08 Cohort, wave 5 and Covid survey, Growing Up in Ireland study)

Discussion and Conclusion

The onset of a global pandemic and its associated socio-cultural disruptions has re-established the importance of researching child development and well-being as it is configured in Irish society. We acknowledge the growing interest in accessing the psycho-social and educational impact of an extensive school closure policy on Irish school-aged children and the role digital technologies played during this liminal time. As a point of departure, we have adopted a class-based approach to play, and how its form and function has evolved alongside rapid social change and challenges (Cullen and Murphy 2020; Coulter and Acqueros-Fernandez 2020). Against this critical framework, play in Ireland displays distinct class, gender and geographical significance. Little attention has been given over to contemplating the ‘play divide’ in Ireland more generally and how this socially determined pattern of play was impacted by the social and educational restrictions put in place in response to Covid-19. Rather, the focus has been on the digital divide within and outside the classroom, be that a virtual class or not. Our analysis of GUI data found that the ‘play divide’ continued during the first lockdown of spring 2020, however, class and geographical location gave rise to more nuance in the configuration of this ‘play divide’. While children spent more time with their families, this ‘indoor time’ took on different significance for children from urban and rural backgrounds. Digital technology was used to remain connected with friends, while children from rural backgrounds tended to spend more time with family than those from urban backgrounds. Researchers are still trying to explain why this may be the case. One possible reason could include the uneven distribution of broadband connectivity across the Republic, where there is better connectivity in Dublin and in more urbanized location compared with rural locations (Central Statistics Office 2021). Urban children have more access to and opportunity for online activities compared to rural children. The lack of affordable and accessible early childcare arrangements in Ireland could also contribute to why families in rural locations have fewer opportunities to be apart (OECD 2021). Children living in manual occupations households also spent less time online, suggesting that the high financial cost associated with being online in Ireland is prohibitive and dissaudes regular use (Pope 2017). These findings confirm that configurations of play are heavily inscribed by class and that the rural-urban divide in Ireland continues to act as a significant social marker of difference in terms of the Irish domestic sphere.

Research into childhood and children in Ireland only emerged in the late 1990s and since then has grown into an area of burgeoning scholarship (e.g. Buckley and Riordan 2017; Hay 2020). This chapter has outlined the knowledge and research gaps in this field of enquiry of the ‘play divide’ in Ireland and explored whether the Covid-19 restriction had an impact on the constitution of this ‘play divide’. While the work is preliminary, it points to the importance of place, space and class in terms of the ‘play divide’ and calls for further work into its consequences as a mediator in the linkage between social class and child outcomes.

Works Cited

Armitage, Richard, and Laura B. Nellums. 2020. ‘Considering Inequalities in the School Closure Response to COVID-19’, The Lancet Global Health, 8: e644, https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(20)30116-9

Arnott, Lorna, and Pauline Duncan. 2019. ‘Exploring the Pedagogic Culture of Creative Play in Early Childhood Education’, Journal of Early Childhood Research, 17: 309-28, https://doi.org/10.26503/todigra.v3i2.67

Aurini, Janice, Rod Missaghian, and Roger Pizzaro Milian. 2020. ‘Educational Status Hierarchies, After-School Activities and Parenting Logics: Lessons from Canada’, Sociology of Education, 93: 173-89, https://doi.org/10.1177/0038040720908

Australian Government Department of Health. 2014. Move and Play Every Day: National Physical Activity Recommendations for Children 0–5 Years (Canberra: Department of Health)

Bennett, Pamela. R, Amy C. Lutz, and Lakshmi Jayaram. 2012. ‘Beyond the Schoolyard: The Role of Parenting Logics, Financial Resources and Social Institutions in the Social Class Gap in Structured Activity Participation’, Sociology of Education, 85: 131-57, https://doi.org/10.1177/0038040711431

Bohnert, Melissa, and Pablo Garcia. 2021. ‘Emerging Digital Generations? Impacts of Child Digital Use on Mental and Socioemotional Well-Being across Two Cohorts in Ireland, 2007–2018’, Child Indicators Research, 14: 629–59, https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-020-09767-z

Brown, Sharon. 2021. ‘Readiness, Barriers and Strategies for Dealing with Unexpected Organisational Change: A Case Study of Irish Secondary Schools During the Covid-19 Pandemic’, unpublished Master’s thesis in Business Administration, Dublin Business School, https://esource.dbs.ie/handle/10788/4314

Bruner, Jerome S. 1972. ‘Nature and Uses of Immaturity’, American Psychologist, 27: 687-708

Buckley, Sarah-Anne, and Susannah Riordan. 2017. ‘Childhood Since 1740’, in The Cambridge Social History of Modern Ireland, ed. by Eugenio Biagini and Mary E. Daly (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), p. 328

Burke, Jolanta, and Marcella Dempsey. 2020. Covid-19 Practice in Primary Schools in Ireland Report (Maynooth, Ireland: Maynooth University Department of Education), https://www.into.ie/app/uploads/2020/04/Covid-19-Practice-in-Primary-Schools-Report-1.pdf

Carver, Alison, Anna Timperio, and David Crawford. 2008. ‘Playing It Safe: The Influence of Neighbourhood Safety on Children’s Physical Activity: A Review’, Health & Place, 14: 217-27, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2007.06.004

Central Statistics Office. 2020. Department of Education Statistics (Dublin: Central Statistics Office),

——. 2021. ‘Internet Coverage and Usage in Ireland 2021’, https://www.cso.ie/en/releasesandpublications/ep/p-isshict/internetcoverageandusageinireland2021/householdinternetconnectivity/

Children’s Research Network. 2020. ‘Growing Up in the Digital Environment’, Children’s Research Digest, 6, https://www.childrensresearchnetwork.org/knowledge/resources/digest-growing-up-in-the-digital-environment

Chin, Tiffani, and Meredith Phillips. 2004. ‘Social Reproduction and Child-rearing Practices: Social Class, Children’s Agency and the Summer Activity Gap’, Sociology of Education, 77: 185-210, https://doi.org/10.1177/003804070407700

Chzhen, Yekatarina, et al. 2022. ‘Learning in a Pandemic: Primary School children’s Emotional Engagement with Remote Schooling during the spring 2020 Covid-19 Lockdown in Ireland’, Child Indicators Research, 15: 1517–538, https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-022-09922-8

Coulter, Colin, and Francisco Arqueros-Fernandaz. 2020. ‘The Distortions of the Irish “Recovery’’’, Critical Social Policy, 40: 89-107, https://doi.org/10.1177/02610183198389

Cronin, Maura. 2007. ‘Class and Status in Twentieth Century Ireland: The Evidence of Oral History’, Soathar, 32: 33-43

Cullen, Pauline, and Mary Murphy. 2020. ‘Responses to the COVID-19 Crisis in Ireland: From Feminized to Feminist’, Gender, Work & Organization, 28: 348-65, https://doi.org/10.1111/gwao.12596

Cullinan, John, et al. 2021. ‘The Disconnected: COVID-19 and Disparities in Access in Quality Broadband for Higher Education Students’, International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, 18: 26, https://ulir.ul.ie/handle/10344/10160

Cybersafe Kids. 2020. Annual Report 2019. https://www.cybersafekids.ie/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/csi_annual_report_2019.pdf

Cybersafe Kids. 2021. Academic Year in Review 2020. https://www.cybersafekids.ie/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/CSK_Annual_Report_2020_web.pdf

Cybersafe Kids. 2022. Academic Year in Review 2021-22. https://www.cybersafekids.ie/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/CSK_YearInReview_2021-2022_FINAL.pdf

Davis, Sara, and Belinda Barrett. 2016. ‘A Gendered Human Rights Analysis of Ebola and Zika: Locating Gender in Global Health Emergencies’, International Affairs, 92: 1049-060, https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2346.12704

Demetriou, Yolanda, et al. 2019. ‘Germany’s 2018 Report Card on Physical Activity for Children and Youth’, German Journal of Exercise and Sport Research, 49: 113–26, https://doi.org/10.1007/s12662-019-00578-1

Devine, D., et al. 2020. Children’s School Lives: An Introduction, Children’s School Lives Report, 1 (Dublin: University College Dublin), https://cslstudy.wpenginepowered.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/CSL-Annual-Report-1-Final.pdf

Doyle, Orla. 2020. COVID-19: Exacerbating Educational Inequalities? (Dublin: Public Policy)

Farley, Thomas A., et al. 2007. ‘Safe Play Spaces to Promote Physical Activity in Inner-City Children: Results from a Pilot Study of an Environmental Intervention’, American Journal of Public Health, 97: 1625-631, https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2006.092692

Flynn, Niamh, et al. 2021. ‘“Schooling at Home” in Ireland during COVID-19: Parents’ and Students’ Perspectives on Overall Impact, Continuity of Interest, and Impact on Learning’, Irish Educational Studies, 40: 217-26, https://doi.org/10.1080/03323315.2021.1916558

Frahsa, Annika, and Ansgar Thiel. 2020. ‘Can Functionalised Play Make Children Happy? A Critical Sociology Perspective’, Frontiers in Public Health, 8: 571054, https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2020.571054

Frost, Joe L. 2010. A History of Children’s Play and Play Environments: Towards a Contemporary Child-Saving Movement (London: Routledge)

Fuchs, Christian. 2020. ‘Everyday Life and Everyday Communication in Coronavirus Capitalism’, triple Cs: Communication, Capitalism & Critique, 18: 375-99, https://doi.org/10.31269/triplec.v18i1.1167

Gentile, D. A., et al. 2017. ‘Bedroom Media: One Risk Factor for Development’, Developmental Psychology, 53: 2340–355, https://doi.org/10.1037/dev0000399

Gosso, Yumi, and Anna Maria Almeida Carvalho. 2013. ‘Play and Cultural Context’, in Encyclopedia on Early Childhood Development, ed. by Richard E. Tremblay, Michel Boivin, and Ray DeV. Peters, https://www.child-encyclopedia.com/play/according-experts/play-and-cultural-context

Government of Ireland. 2018. Action Plan For Online Safety 2018-2019, https://assets.gov.ie/27511/0b1dcff060c64be2867350deea28549a.pdf

Hale, Thomas, et al. 2021. ‘A Global Panel Database of Pandemic Policies (Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Tracker)’, Nature Human Behaviour, 5: 529–38, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-021-01079-8

Hay, Marnie. 2020. ‘Centuries of Irish Childhoods’, Irish Economic and Social History, 47: 3-9, https://doi.org/10.1177/0332489320950077

Helsper, Ellen. 2021. The Digital Disconnect: The Social Causes and Consequences of Digital Inequalities (London: SAGE)

Holloway, Sarah L, and Helena Pimlott-Wilson. 2014. ‘Enriching Children, Institutionalizing Childhood? Geographies of Play, Extracurricular Activities, and Parenting in England’, Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 104: 613–27, https://doi.org/10.1080/00045608.2013.846167

Horgan, Denis, et al. 2020. ‘Digitalisation and COVID-19: The Perfect Storm’, Biomedicine Hub, 5: 1-23, https://doi.org/10.1159/000511232

Humphreys, Eileen, Des McCafferty, and Ann Higgins. 2011. How Are Our Kids? Experiences and Needs of Children and Families in Limerick City with a Particular Emphasis on Limerick’s Regeneration Areas (Limerick: Limerick City Children’s Services Committee)

Kelly, Lisa, et al. 2022. Growing Up in Ireland: A Summary Guide of the COVID-19 Web Survey for Cohorts ’08 and ’98 (Dublin: n.p.), https://www.growingup.ie/pubs/20210909-Summary-Guide-Covid-Survey.pdf

Kernan, Margaret, and Dympna Devine. 2010. ‘Being Confined Within? Constructions of the Good Childhood and Outdoor Play in Early Childhood Education and Care Settings in Ireland’, Children and Society, 24: 371–85, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1099-0860.2009.00249.x

Knight, Sara. 2009. Forest Schools & Outdoor Learning in the Early Years (London: Sage)

Lareau, Annette. 2000. ‘Social Class and the Daily Lives of Children: A Study from the United States’, Childhood, 7: 155–71, https://doi.org/10.1177/09075682000070020

——. 2003. Unequal Childhoods: Class, Race, and Family Life (Berkeley: University of California Press)

Lee, Eun-Young, et al. 2021. ‘Systematic Review of the Correlates of Outdoor Play and Time among Children aged 3-12 Years’, International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 18: 41, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-021-01097-9

McBride, Deborah L. 2012. ‘Children and Outdoor Play’, Journal of Pediatric Nursing, 27: 421-22, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pedn.2012.04.001

Mohan, Gretta, et al. 2020. Learning for All? Second-Level Education in Ireland During Covid-19, ESRI Survey and Statistical Report Series, 92, https://www.esri.ie/pubs/SUSTAT92.pdf

National Advisory Council for Online Safety. 2021. Report of a National Survey of Children, their Parents, and Adults regarding Online Safety 2021, https://www.gov.ie/en/publication/1f19b-report-of-a-national-survey-of-children-their-parents-and-adults-regarding-online-safety/?referrer=http://www.gov.ie/onlinesafetyreport/

O’Connor, Pat. 1992. Friendships Between Women: A Critical Review (New York: Guilford Press)

OECD. 2021. Country Note: Ireland, https://www.oecd.org/education/school/StartingStrongVI-CountryNote-Ireland.pdf

McCoy, Selina, Amanda Quail, and Emer Symth. 2012. Growing Up in Ireland: Influences on 9 Year Olds’ Learning: Home, Schooling, and Community, Child Cohort Research Report, 3 (Dublin: Government Publications), https://www.growingup.ie/pubs/BKMNEXT204.pdf

O’Carroll, John Patrick. 1987. ‘Strokes, Cute Hoors and Sneaking Regarders: The Influence of Local Culture on Irish Political Style’, Irish Political Studies, 2: 77-92

O’Neill, Brian, Simon Grehan, and Kjartan Olaffson. 2011. Risks and Safety for Children on the Internet: The Ireland Report (London: LSE EU Kids Online), https://www2.lse.ac.uk/media-and-communications/assets/documents/research/eu-kids-online/participant-countries/ireland/IrishReport.pdf

O’Neill, Brian and Thuy Dinh. 2013. Children and the Internet in Ireland: Research and Policy Perspectives, Digital Childhoods Working Paper Series, 4 (Dublin: Technological University Dublin), https://arrow.tudublin.ie/aaschmedcon/32/

——. 2015. Net Children Go Mobile: Full Findings from Ireland (Dublin: Technological University Dublin), https://arrow.tudublin.ie/cserrep/55/

Pope, Conor. 2017. ‘Ireland One of the Priciest Developed Countries for Broadband’, Irish Times, 17 November, https://www.irishtimes.com/news/ireland/irish-news/ireland-one-of-priciest-developed-countries-for-broadband-1.3298978

Powell, Elizabeth C., Erin J. Ambardekar, and Karen M. Sheehan. 2005. ‘Poor Neighborhoods: Safe Playgrounds’, Journal of Urban Health, 82: 403–10, https://doi.org/10.1093/jurban/jti099

Power, Martin. J., et al. 2012. An Introduction to Irish Society: Transitions and Change (Essex: Pearson)

Public Health England. 2020. Disparities in the Risk and Outcomes of COVID-19, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/908434/Disparities_in_the_risk_and_outcomes_of_COVID_August_2020_update.pdf

Raharja, Anthony, Alice Tamara, and Li Teng Kok. 2021. ‘Association between Ethnicity and Severe COVID-19 Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis’, Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities, 8: 1563-572, https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-020-00921-5

Rao, Nirmala, and Phillip A Fisher. 2021. ‘The Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on Child and Adolescent Development around the World’, Child Development, 92: e738-e748, https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.13653

Richardson, Dominic, et al. 2020. Supporting Families and Children beyond COVID-19: Social Protection in High-Income Countries (UNICEF Office of Research: Innocenti), http://hdl.handle.net/10993/44976

Roopnarine, Jaipaul L., and Kimberly L. Davidson. 2015. ‘Parent-Child Play access Cultures: Advancing Play Research,’ American Journal of Play, 7: 228-52

Rowicki, Slawa and Mark McGovern. 2018. ‘Unequal Opportunities for Play? How Children Spend their Time in Ireland,’ Children’s Research Digest, 5: 11-19, https://childrensresearchnetwork.org/knowledge/resources/unequal-opportunities-for-play-how-children-spend-their-time-in-ireland

Sandseter, Ellen Beate Hansen. 2011. ‘A Quantitative Study of ECEC Practitioners’ Views and Experiences on Children’s Risk-taking in Outdoor Play’, unpublished paper presented at the 21st EECERA conference, Education from Birth: Research, Practices and Educational Policy

Smahel, David, Machackova, Hana, Mascheroni, Giovanna, Dedkova, Lenka, Staksrud, Elisabeth, Ólafsson, Kjartan, Livingstone, Sonia and Uwe Hasebrink. 2020. EU Kids Online 2020: Survey results from 19 countries (Issue February, pp. 156–156). https://doi. org/10.21953/lse.47fdeqj01ofo p.19.

Stirrup, Julie, John Evans, and Brian Davies. 2017. ‘Learning One’s Place and Position through Play: Social Class and Educational Opportunity in Early Years Education,’ International Journal of Early Years Education, 25: 343-60, https://doi.org/10.1080/09669760.2017.1329712

Sze, Shirley, et al. 2020. ‘Ethnicity and Clinical Outcomes in COVID-19: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis’, EClinicalMedicine, 29: 100630, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100630

Timperio, Anna et al. 2004. ‘Perceptions about the Local Neighborhood and Walking and Cycling among Children’, Preventive Medicine, 38: 39-47, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2003.09.026

Tremblay, Mark, et al. 2015. ‘Position Statement on Active Outdoor Play’, International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 12: 6475–505, https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph120606475

Veitch, Jenny, et al. 2006. ‘Where Do Children Usually Play? A Qualitative Study of Parents’ Perceptions of Influences on Children’s Active Free-Play’, Health & Place, 12: 383-93, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2005.02.009

Vincent, Carol, and Stephen J. Ball. 2007. ‘”Making up” the Middle Class Child: Families, Activities and Class Dispositions,’ Sociology, 41: 1061-077, https://doi.org/10.1177/0038038507082315

Viscaovky, Sergio E. 2017. ‘When Time Freezes: Socio-Anthropological Research on Social Crises’, Iberoamericana-Nordic: Journal of Latin American and Caribbean Studies, 46: 6-16, https://doi.org/10.16993/iberoamericana.103