5. How Playwork in the United Kingdom Coped with Covid-19 and the 23 March Lockdown

© 2023, Pete King, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0326.05

Introduction

On 23 March 2020, the British Prime Minister announced a UK-wide lockdown in response to a new β-coronavirus, SARS-CoV-2 or Covid-19 (Dickson 2020). All playwork provisions closed immediately except for settings that provided childcare for parents and carers who were ‘key workers’ and therefore still working. This included health and social care, education and childcare, key public services, local and national government, food and other necessary goods, public safety and national security, transport and utilities, communication and financial services (Department for Education 2020).

As playworkers were not considered key workers, this resulted in the closure of adventure playgrounds and out-of-school clubs, as well as local parks and open spaces, unless the setting supported a local authority ‘cluster or hub’ (King 2020; Department for Education 2020). This was a single location serving a cluster of schools where the children of critical workers, later extended to include vulnerable children as well, were schooled and looked after at the end of the school day whilst their parents continued to work.

On a playwork social media online forum, one person posted the following question: ‘Could playwork be considered as a key working role?’ This question resonates with the development of playwork since the early play clubs in the 1900s, the development of the adventure playground movement in the 1950s and, more recently, the conference paper by Gordon Sturrock and Perry Else about the playground as therapeutic space and playwork as healing (1998). The question seemed worth investigating further and formed the start of a year-long, longitudinal study, as described in this chapter.

Playwork is a profession that has roots in the United Kingdom but examples of playwork practice are also evident in other countries, such as The Netherlands (van Rooijen 2021), the USA (Patte 2018) and Hong Kong (Chan et al. 2020). Within the UK, playwork has been defined as ‘a highly skilled profession that enriches and enhances children’s play. It takes place where adults support children’s play, but it is not driven by prescribed education or care outcomes’ (SkillsActive 2010: 2).

This chapter starts with a brief historical account of the development of playwork in the UK up to the present day from two similar, yet very different origins. The chapter then focuses on four research studies into Covid-19 and playwork undertaken between March 2020 and March 2021. All of these studies were undertaken by the author and each was ethically approved by the College of Human and Health Science, Swansea University. They involved a study at the start of the March 2020 lockdown on how playwork responded to the pandemic and how playworkers had to adapt upon re-opening their gates and doors in July 2020. The study included practitioners and children at adventure playgrounds and after-school clubs across the United Kingdom. The chapter concludes by reviewing how the versatile and adaptable nature of playwork has enabled it to continue to support children and young people’s play in the United Kingdom.

Historical Pathways

1) Adventure Playgrounds

Adventure playgrounds evolved from the idea of the ‘junk playground’ by the landscape architect Carl Theodor Sørensen (1931) and the first one opened on 15 August 1943 at Emdrupvej (sometimes referred to as Emdrup) (Cranwell 2003a), just outside Copenhagen. After visiting Emdrup in 1946, Lady Allen of Hurtwood (Allen 1968) brought the idea to the United Kingdom. The first public ‘junk playground’ is reported to have been set up in 1948 in Camberwell, London, by a voluntary association (Benjamin 1961). With the involvement of the National Playing Fields Association (NFPA, now called Fields in Trust) (Norman 2003), ‘junk playgrounds’ were re-named ‘adventure playgrounds’ (Cranwell 2008) in a leaflet published by the NPFA (Newstead 2017).

The child-led nature of the adventure playgrounds, which is still reflected in the Playwork Principles (Playwork Principles Scrutiny Group 2005) and according to which adults should support children’s play, has been documented across the UK, for example, in London, Liverpool, Bristol and Grimsby (Benjamin 1961), Crawley (Shier 1984), Peterborough, Stevenage and Telford (Chilton 2003), Reading, Preston and Welwyn Garden City (Lambert and Pearson 1974). These adventure playgrounds were supported by a combination of voluntary committees, local authorities and the NPFA (Cranwell 2003a). Although the number of adventure playgrounds has declined since the 1970s (Chilton 2018) due to the impact of increasing health and safety regulations (Chilton 2003), for example, they are still run by voluntary committees, with funding in some cases provided by the local authority or through funding grant applications.

2) Children’s Play Centres

The second pathway has been traced by Cranwell (2003b), who provides a historical account of the evolution of play settings in London between 1860 and 1940 where the ‘major function of supervised out-of-school provision was to assist the state in maintaining the responsibility of working-class families to provide and protect their children in the community’ (Cranwell 2003: 33). In London, the nineteenth century saw the beginnings of supervised clubs which resemble today’s out-of-school provision. The supervised clubs included the Mary Ward and the Passmore Edwards Settlements, and the play centres opened by the Children’s Happy Evening Association (CHEA) (Bonel and Lindon 1996; Homes 1970).

The Children’s Happy Evening Association opened their first play centre in Marylebone, London in 1888 (Holmes and Massie 1970; Martin 1999), and by 1914 ran between ninety-four (Taylor 2013) and ninety-six (Holmes and Massie 1970) play centres in London and ten outside of London. In 1897, the Passmore Edwards Settlement (Holmes and Massie 1970) set up the Passmore Edwards Children’s Recreation Schools which were founded by the novelist and philanthropist Mary Ward (Rappaport 2001). These developed from a Saturday morning ‘playroom’ at Marchmont Hall, St. Pancras in 1897, attended by ‘two batches of 120’ children (Trevelyan 1920: 2). Free evening and weekend play clubs were also set up to offer ‘poor children respite from slum life and provide the first tentative moves towards combating juvenile delinquency’ (Rappaport 2001: 731). These play clubs were funded through a combination of private financial donations and, with the passing of the Education (Administrative Provisions) Bill in 1907, through local authorities (Trevelyan 1920). In London, play centres were initially run by the CHEA, and the Passmore Edwards Children’s Recreation Schools were taken over by London County Council from the 1940s up until 1990 (Cranwell 2003).

From Play Centres to the Childcare Agenda

During the 1990s and 2000s, funding was made available initially by the Conservative government in 1993 through the Out-of-School Childcare Initiative (Saunderson et al. 1995), and then by the Labour government’s drive to increase quality, affordable and accessible childcare (Department for Education and Employment 1998) and out-of-school care (breakfast clubs, after-school clubs and holiday play schemes) that parents paid for their children to attend (unlike the CHEA, which was free). Although the increasing focus on childcare provision contributed to a decline in adventure playgrounds (Chilton 2003), by the 2000s there was an increase in the number of out-of-school provisions opened in primary schools (and other community venues) across the UK.

In 1993, the Conservative government provided funding for the Out-of-School Childcare Initiative (OSCI) (Education Extra 1997), also known as the Out-of-School Childcare Grant (OSCG) (Saunderson et al. 1995). OSCI/OSCG was introduced in April 1988, to provide set-up costs for out-of-school childcare (Saunderson et al. 1995) but the out-of-school clubs were reliant on fee-paying parents and carers. Within the first year of the OSCI/OSCG, two hundred different schemes had been created, providing 4400 childcare places (Saunderson et al. 1995). At the same time that the OSCI/OSCG funding finished, the UK government also changed from Conservative to Labour.

The New Labour government continued the drive to increase the workforce by providing funding to create childcare places under the National Childcare Strategy (NCS) (Department for Education and Employment 1998). The NCS was intended to support the existing voluntary sector, which was the main childcare provider, and the childcare business sector ‘to ensure quality affordable childcare for children aged 0 to 14 in every neighbourhood, including both formal childcare and support for informal arrangements’ (Department for Education and Employment 1998: 11) and to create ‘40,000 extra childcare places’. By the 2000s the number of out-of-school clubs saw a huge rise in provision (breakfast clubs, after-school clubs and holiday play schemes) (Smith and Barker 2000).

In 2020, despite limited funding opportunities due to government funding ending and the introduction of austerity measures (Voce 2015), both out-of-school provision and adventure playgrounds run by playworkers or adults who use a playwork approach remained. Although exact numbers for out-of-school provision in the UK are difficult to specify, the number of childcare settings in the UK was 13,380 (including day care, nursery and out-of-school settings) (Office for National Statistics 2015). It is also estimated that there are about 125 adventure playgrounds still operating in the UK. From the time of the 1900 play clubs to the development of the adventure playgrounds movement in the 1940s, and the recent childcare revolution, playwork fulfils an important role in some children’s lives in the UK.

The Community Element of Playwork

It has been proposed that adventure playgrounds and after-school clubs might be considered as a form of community of practice (CoP) (King and Newstead 2020; King 2021a, 2021b), where CoP is defined as

[A] group of people who share a passion, a concern, or a set of problems regarding a particular topic, and who interact regularly in order to deepen their knowledge and expertise, and to learn how to do things better. A CoP is characterized by mutual learning, shared practice, inseparable membership, and joint exploration of ideas. (Mohajan 2017: 1)

The CoP of playwork can be traced back to the early days of the children’s play centres and the subsequent growth of out-of-school provision (King 2021b) as well as the development of the adventure playground movement (King 2021a). For example, a CoP for adventure playgrounds has developed shared goals which are found in the twelve key elements for adventure playgrounds (Play England 2017), developed by those who work in them. However, the 2020 global event of Covid-19 created a new ‘concern or a set of problems regarding a particular topic’ to which the playwork community needed to respond.

The Introduction of Lockdown and the Impact on Playwork

The 23 March lockdown impacted everybody’s lives, both professionally and personally. For this reason, and the unique nature of the situation, it was important to undertake research into how playwork would be affected by the pandemic at the time, rather than retrospectively. This initial study turned into an eighteen-month longitudinal study from March 2020 to September 2021, when all settings were able to re-open, and during subsequent lockdowns between October 2020 and March 2021. In total, eight research studies were undertaken of which four, from the period March-July 2020, are the focus here.

Study 1 was undertaken in March 2020 during the first UK lockdown. It involved interviewing twenty-three participants recruited from across the UK (see King 2020a for more details). Study 2 was undertaken after playwork settings re-opened in July 2020 as lockdown restrictions were eased. It involved interviews with eighteen adventure playground workers in England and Wales (King 2021a). Study 3 was also undertaken in July 2020, with fifty-four participants from across the UK completing an online survey (King 2021b). Study 4 was undertaken in March and April 2021, one year after settings re-opened in July 2020. Nine headteachers in Torfaen Borough Council, Wales, were interviewed about their perception of ‘well-being playworkers’ (see King 2021d for more details). The studies were UK-wide which meant that, following the initial lockdown, the restrictions (e.g. the social distancing measures in force in playwork settings) at the time of each study may have differed from one part of the UK to another.

Study 1: Can Playwork Be Considered an Essential Worker Role?

This first study explored three aspects of playwork practice from the March 2020 lockdown: the notion of playwork as a key work role, the immediate impact of Covid-19 and lockdown on playwork settings, and the question of how playwork would be undertaken post-lockdown.

When asked about their understanding of a ‘key worker’, playworkers in the study viewed the role as a response to the current situation, which was necessary to support the maintenance of the health and well-being of all citizens, and providing care to an individual (King 2020). In this sense, playworkers viewed themselves as key workers during the pandemic. In particular, they viewed playwork as supporting key worker parents and carers by providing childcare as part of a school ‘hub’. This not only enabled parents and carers to carry out their work but also gave them peace of mind that their children were in an environment where they could enjoy themselves. This was important as not all children had access to childcare settings during lockdown:

So, I think the number one thing is it allows the parents to do their jobs, that’s the number one thing right now. But the second thing, which is what the parents keep saying to me, is how the difference it makes to them knowing that their kids are happy, they’re safe, they’re well cared for, their needs are being met. (Manager of an after-school club and holiday play scheme, England)

The theme of a playwork approach also emerged from the data. A playwork approach is summed up in the second playwork principle:

Play is a process that is freely chosen, personally directed and intrinsically motivated. That is, children and young people determine and control the content and intent of their play, by following their own instincts, ideas and interests, in their own way for their own reasons (Playwork Principles Scrutiny Group 2005: 1)

Playwork focuses on the process of play, rather than any adult-directed purpose or outcome. This approach is one of the unique ways in which playworkers define their work (King 2015), where children and young people have control and autonomy in play as to how, where, with whom, and what. The implications of this approach, not only during lockdown but afterwards too, are summed up in the comment below:

I just think as a playworker, you’ve got no agenda, you’re there just to facilitate. And I think that, during these times, that approach would be a massive help to children, young adults [and] vulnerable individuals. And thinking about how we’re going to impact on it. Going back is going to be a challenging time for all the staff, for all the children and all the parents. (Manager of a Wraparound Play Company, Wales)

A third theme that emerged was that of relationships and this reflected the important role of playwork, not just for the children and young people who attend playwork settings, but regarding relationships within the community, including for parents and carers:

I would like now to think we’re proving our worth, that we don’t just play pool and table tennis, we are a vital part of the families on our estate, a vital part of their lives as well. We are key to them. So that surely makes us keyworkers? (Senior Playworker of an Adventure Playground, England)

Study 1 thus indicated that playwork was considered important not only in supporting key workers as defined by the government but was also a key worker role in itself. The second part of this study explored how playwork settings responded to the onset of lockdown and their thoughts on how playwork should continue once the lockdown eased.

At the start of the 23 March lockdown, playwork settings fell into one of three categories (King 2021c). The first category was settings that immediately closed, with all staff put on furlough, i.e. eighty percent of staff members’ pre-Covid salaries were paid through the UK Government’s ‘coronavirus job retention scheme’ (Pope and Shearer 2021). In this category, all staff ceased work and settings remained shut. For other playwork settings, one or two staff members remained employed (whilst other staff members were put on furlough) but no face-to-face playwork took place. Instead, some settings developed an ‘outreach’ play service where resources were left outside houses for children to collect and use. The example below is based on the ‘Theory of Loose Parts’ (Nicholson 1971) which states that the more resources (loose parts) children can play with, the more ideas are created in their play:

We came up with this ‘bags for play’ idea where we are getting bags of loose parts out to children across the county. Particularly children who are living in disadvantaged areas or who have got social care interventions, so we’re trying to get the bags out to the children who need them most. We are being true to our roots in the fact that the bag is full of stuff so it’s not obvious what you may do with it. There’s a bit of active stuff like skipping rope, balloons, chalk. Nice tin of water colour paints and paper. Scissors, some tape, some glue, some scrap, so it’s very much true to what we do, no directions on how to use it. (Playworker for an Open Access Mobile Play Provision, England)

Some settings engaged in online interaction, running virtual play sessions, although with varying success, as indicated in the comment below:

I’m recording videos of Mr Men videos and putting that on our website and sharing that around. We get a little bit of engagement from the parents who follow our social media, and a couple of the kids who follow our social media. But to be honest, it’s a tiny fraction. I’m happy to do that and I think it provides value but the amount of value it provides in comparison to being open for play, it’s obviously going to be really a tiny fraction. (Manager of an Adventure Playground, England)

Certain other settings remained open but changed their focus to support families in the communities where they were located. For example, some adventure playgrounds became, or expanded on, food bank provision:

Quite a few families have got in touch, so the playground is kind of providing a food bank service to some of the families and other people in the community. That is still providing a service to the community although it’s not adventure play. (Manager of an Adventure Playground, England)

A change in focus emerged, with playworkers supporting primary school teachers in running the ‘hubs’ for key worker and vulnerable children:

Well, in regard to the service which we run seven days a week at the moment, all our provisions are closed, but we’ve been asked to co-ordinate and run the hubs, five hubs across the authority plus one for the special needs school. So, we are not running those play spaces or staffed play spaces, we are supporting the hubs’ staffed provision for children that attend that. It’s not open to all. It started first for blue light services, second it was open to any front-line services and, as from Monday, we are looking at looked-after children to be supported and have play opportunities as well. (Play Service Manager, Wales)

This example of a play service that ended up coordinating the hubs resulted in a follow-up study (Study 4), which is described in more detail later on in this chapter. Participants in the first study were also asked how they thought playwork would be able to continue post-lockdown. This led to the emergence of three themes: reduced or no playwork provision, developing new methods of delivering playwork, and the need for a more therapeutic role (King 2020).

Some feared the worst-case scenario, i.e., that playwork settings would not be able to continue, particularly those in the childcare sector who rely on parents and carers paying for their children’s attendance at sessions. With most parents and carers working from home, many playwork settings in the out-of-school sector were worried about the numbers of children who would use the provision post-lockdown:

We closed on the 23rd March as the schools shut but we were able to open during Easter which meant the staff could go off on their break. I had staff I could bring in who weren’t furloughed, and we were able to open and offer cover for children. We made a loss, I would say, of £800+ that week, that fortnight. (After-school Club Manager, Wales)

Whilst funding was one issue, another was the strong possibility that the introduction of two-metre social distancing would continue in playwork settings and that playworkers would have to develop new ways of doing their job, as reflected in the comment below:

We’ve fought against funding cuts and, as a profession, we’re fighting back against stuff we don’t like. This is something we don’t like but we can’t fight because we’ve got to keep children apart which doesn’t sit well with any of us. We are just going to have to roll with it and accept this is the situation and how do we make it good. It is fairly rubbish and we’ve got to kind of keep it kind of happy and move on really. (Play Development Worker, Wales)

With children and young people experiencing lockdown and not being able to play in the same physical space as their friends and peers, there was a genuine feeling that the therapeutic aspects of playwork would be most required when children returned to the settings:

So, for sure, there is going to be a high level of need and I’m expecting that our targeted support that we do, our play nurturing work, that could be very much on the up. You know people will have a real appreciation of children who are experiencing high levels of anxiety from what they’ve been through and the need for them to have opportunities to play in small groups or as individuals with our playworkers. (Playworker for Open Access Mobile Play Provision, England)

In July 2020 playwork settings began to re-open, although with many restrictions. It was decided that follow-up research was needed to see how playwork generally, and the different playwork settings, were able to operate. As noted above, this resulted in two further studies, one with adventure playgrounds and mobile play provision, and the other with out-of-school clubs (breakfast clubs, after-school clubs, and holiday play schemes).

Study 2: Adventure Playgrounds and Mobile Play Provision Post-Lockdown

Study 2 involved interviewing adults who work within adventure playgrounds or who offer mobile play provision in children’s and young people’s local parks and open spaces. Pre-Covid, these two types of provision were ‘open access’:

This provision usually caters for a wide age range of children, normally aged five years and over. The purpose is to provide staffed play opportunities for children, usually in the absence of their parents. Children are not restricted in their movements, other than where related to safety matters and they are not prevented from coming and going as and when they wish. (Welsh Government 2016)

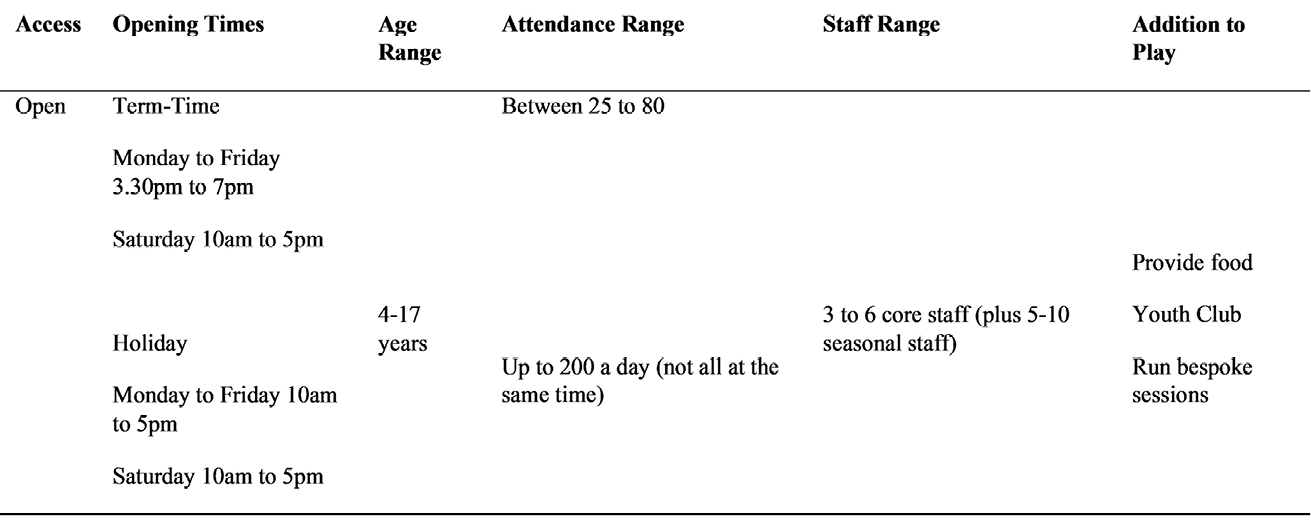

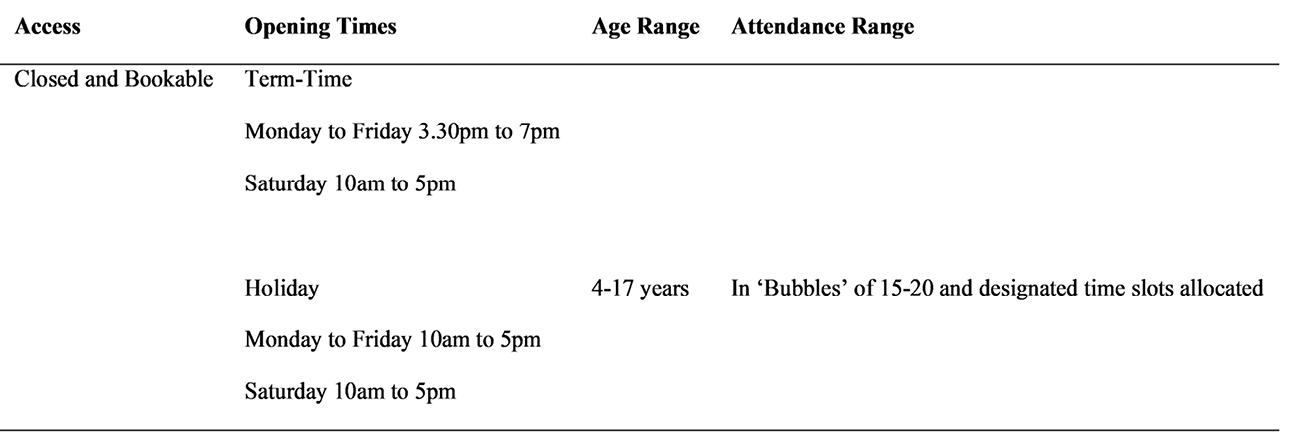

Here, children are free to come and go as they please. They do not have to stay if they choose not to. During the interviews, participants were asked how their setting ran both pre- and post-lockdown. The difference can be seen in Figures 5.1 and 5.2 below:

Figure 5.1 A ‘typical’ adventure playground, pre-March 2020 lockdown (data from King 2021a)

Figure 5.2 A ‘typical’ adventure playground, July 2020 (data from King 2021a)

CC BY-NC 4.0

The exact ‘change in playwork practice’ identified and feared in the first study became a reality, in that settings had to change from open access, with children free to arrive and leave at their will, to a closed-access, bookable provision. This resulted in fewer children using the settings. In addition, the need for a Covid-19 risk assessment increased paperwork and cleaning. This led to reduced availability of resources, particularly the ‘loose part’ objects which now had to be rotated and cleaned. There was also less space for children to use as they were in small groups or ‘bubbles’ and rotated between designated areas at different time slots. This was a big change from pre-lockdown playwork practice:

The children didn’t have the control they normally have over what they were doing, which is what play is all about, isn’t it? You could argue this was activity rather than play. Because they chose to be there. I assumed they did because they turned up, the parents brought them and stuff like that and they wanted to be there. They had a good time. It was different to what they normally access in the playground. There was an element of fluidity there, if they wanted to go on a slide they would go on the slide, but it was not as free-range as it would normally be as you had to stay in these bubbles and stay separate from the other bubbles. So it was far more structured, which goes against the grain completely, you know what I mean? The activities could be adapted to some degree, but it wasn’t as fluid and responsive as it normally would have been. (Manager of an Adventure Playground, England)

This reflection indicates how the ‘playwork approach’ of supporting the process of play was forced to ‘change’ in order for children to attend once again. This was quite a challenge for those using, and used to, a ‘playwork approach’ in their practice but it reflects the need for playworkers as a community of practice to continually adapt to solve ‘shared problems’ (Mohajan 2017). Thus, the main themes that emerged from the interview data were preparation for opening (increased cleaning and paperwork), reduction (in playwork ethos, children attending, resources and space), targeted service (for both new and existing users) and play behaviour (anxiety about returning and having to play with social distancing measures) (King 2021a).

Study 3: Out-of-School Settings (Breakfast Club, After-School Club and Holiday Play Scheme) Post-March 2020 Lockdown

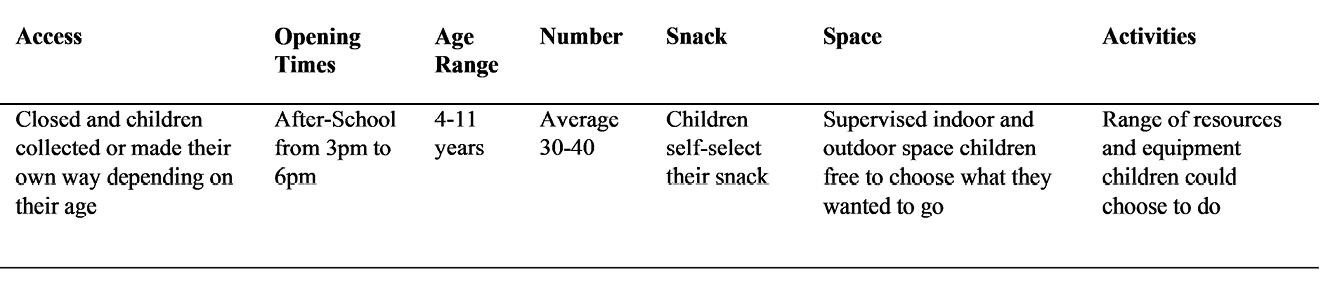

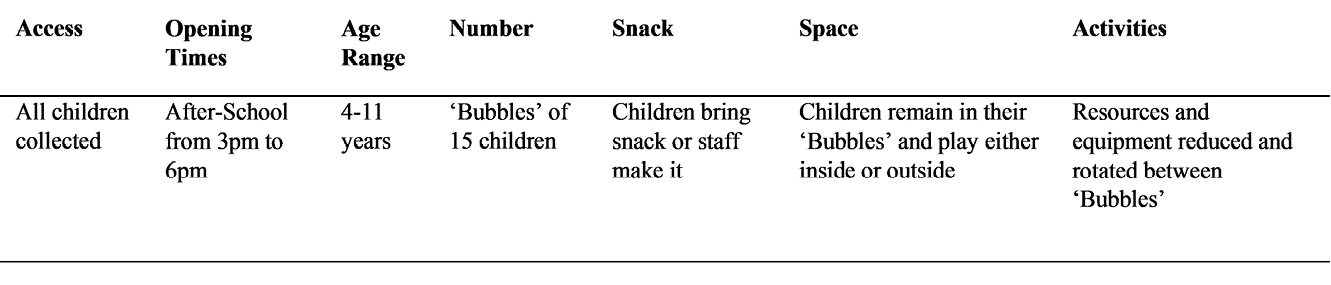

The ‘shared problems’ also related to Study 3 which focused on the closed-access out-of-school clubs. Closed access in this instance designates the need for children to be booked in for sessions and to stay until collected by their parent, carer or other adults. Study 3 was an online survey. As with Study 2, participants were asked to describe a typical session pre-March 2020 lockdown and their experience at re-opening in July 2020. This is shown in Figures 5.3 and 5.4 below:

Figure 5.3 A ‘typical’ after-school club, pre-March 2020 lockdown (data from King 2021b)

CC BY-NC 4.0

Figure 5.4 A ‘typical’ after-school club, July 2020 (data from King 2021b),

CC BY-NC 4.0

As with Study 2, Study 3 also saw a reduction in the number of children attending, the resources available and the space in which to play (King 2021b). Although there was also an increase in cleaning and paperwork, Covid-19 policies and reporting measures had to be put in place, resulting in more forms to complete. Children had to remain in ‘bubbles’ consisting of a group of no more than fifteen children (Public Health England 2020). A bubble would often be the same as the children’s year group bubble at their school. It was necessary to ensure that enough staff were employed for the number of bubbles:

The segregation of children into bubbles is the biggest headache for me. I am lucky that we have always worked with surplus staff (minimum of 1:8 adult-to-child ratio, and usually more like 1:6). This means I now have enough staff to support each bubble (so 7 separate sets of children) and still serve snack to 72 children, but running the setting would be so much easier and more fun for the children if they could play with each other. (Manager of out-of-school provision, England)

As in Study 2, playworkers had to change their ‘playwork approach’ which previously involved children choosing what they wanted to play with. Four themes are related to this change in practice: maintaining service (increased policies, cleaning and financial concerns), bubbles (placement of children in year groups or age groups), play space (which had to be rearranged with designated resources and mostly outdoors), and play behaviour (more one-to-one with adults and, upon return, play behaviour was challenging) (King 2021b). As with the adventure playgrounds and mobile play provision, the closed-access, out-of-school provision led to ‘shared problems’ related to facilitating a play environment with fewer children, resources and space. With many out-of-school settings based in schools, the increased paperwork and greater number of staff required for bubbles made these changes specific to school-based playwork settings. Different solutions to open-access provision were needed.

The need for flexibility in playwork was anticipated by the participants in Study 1. It can be traced back to early play centres and adventure playgrounds, where issues of funding, resources and staff retention were commonplace, and remain so in different playwork settings today. It could be argued that the adaptability and versatility of playwork arises from its focus on the process of play and that this enables playworkers to respond to different situations, from adventure playgrounds to children’s hospital wards. Study 4 showed how an established team of playworkers was able to respond to the sudden lockdown by coordinating and running school hubs, supported by teaching staff (King 2021d).

Study 4: ‘Well-being’ Playworkers

As noted above in Study 1, one playwork provider was asked to coordinate and run hubs. This was the play service of Torfaen Borough Council in South-East Wales. Torfaen Borough Council has had a play service since 2004 and, prior to Covid, provided community play provision including holiday play schemes, family sessions and respite sessions, as well as support for schools before and after the school day and during school breaktimes. During the lockdown, the play service playwork team changed their job title to ‘well-being playworkers’ to reflect their new focus of supporting children and young people. During the first lockdown in March 2020, the same well-being playworkers were allocated to one of the six hubs in Torfaen, working with the teaching staff who were scheduled to work that day. This proved to be very successful and led to Study 4, which involved interviewing the headteachers linked to each of the six hubs about their views of the well-being playworkers.

The headteachers from the six primary schools to which the six hubs were attached were asked for their views on the well-being playworkers during the first lockdown and after it was eased in July 2020. Three clear themes emerged: strong relationships (with the children, staff and school, and the wider community), the fact that these playworkers were a part of the school team (running the lockdown hubs, offering bespoke provision and providing academic support), and provided quality service (with their adaptable play practice, trained staff and resources provided). Some of the headteachers had had experience of the play service before lockdown but for others these hubs were the first experience. There was a clear similarity between the themes and subthemes that emerged from the headteachers in this study (i.e., the importance of relationships and adaptable play practice) and those that emerged from Study 1 involving playwork professionals.

The Torfaen play service, as with many other play organizations across the UK, was already familiar with the hub concept since this is often applied for holiday play schemes and open-access adventure playgrounds. What was evident and acknowledged by the headteachers and school staff working in the hubs was that well-being playworkers undertook a playwork approach with children in formal education. The well-being playworkers, and importantly the same playworkers attending the same hubs each day, provided some day-to-day consistency for the children with a familiar face. The more informal approach of the well-being playworkers, for instance the fact that they were addressed by their first names), provided what Burghardt (2005) termed a ‘relaxed field’ that enabled children to play, with the well-being playworkers supporting the process of play:

It’s the way they just interact with the children, and they chat to the children, and I suppose the activities that they do, like the sporting activities, the creative activities, the fact they are a constant. (Headteacher 2, Wales)

This is not to say that teaching staff played an unimportant or passive role but the well-being playworkers were more experienced and skilled in their ability to adapt quickly in developing the hub (King 2020), which the play service had been running in the community since 2004 via holiday play schemes in Torfaen.

The designation of playwork as a key worker role in terms of ‘relationships’ and ‘adaptability’ in Study 1 was perceived by playwork professionals, whilst in Study 4 it was acknowledged by headteachers. The two different perspectives indicate the importance of play, and playworkers, in supporting children, families and schools during the first lockdown and beyond.

Conclusion

As argued throughout this chapter, playwork has always had to be adaptable and versatile and this was evident in many ways during the lockdown period. For example, as a result of austerity and welfare reform, there has been an increase in the number of food banks (Lambie-Mumford and Green 2015) which resulted in some adventure playgrounds either forming or increasing food-bank provision. This is not new in playwork praxis considering that the formation and development of the nineteenth-century play clubs and 1950s adventure playgrounds took place in low socio-economic communities:

Most playwork is done in areas of chronic emotional, cultural and often financial deprivation. If this were not so, the needs for [adventure] playgrounds of this kind and criticisms of the environments in which they are placed would only be minimal. (Hughes 1975: 2)

The more recent out-of-school clubs did not become food banks but they supported children and young people in different ways by providing services and running at a loss. Although not sustainable, this demonstrated playwork’s flexibility during the lockdown period and beyond.

The four research studies included in this chapter contribute to the social history of playwork during the pandemic. The four studies considered the lived experience of the participants as they were experiencing lockdown and the effects of Covid-19 on a professional level. Changes had to be put in place and this relied on the sharing of ideas and problems that did occur during the pandemic for both adventure playground and mobile play provision (King 2021a) and the out-of-school club sector (King 2021b).

Whilst schools and other childcare-related settings were provided with government guidance upon re-opening, this was not the case for many playwork settings. Instead, guidance to adapt settings often came through other sources, such as London Play, who developed guidance for adventure playgrounds.

From a playwork praxis perspective, the current Covid-19 pandemic has shown how playwork adapted and demonstrated versatility to support children, young people and their families within their communities. Whether this involved providing food, delivering play resources or virtual play sessions, playwork continued, if not directly face-to-face. Where face-to-face delivery was still undertaken, this occurred in very controlled conditions and during the lockdown within the local authority hubs. The very nature of playwork praxis, such as not knowing which children may attend at a given time (as in pre-Covid open access) or having different children booked into after-school clubs and holiday play schemes, enabled a ‘playwork approach’ to supporting the provision of play for hub teaching staff and, in the case study outlined here, coordinating the hubs. The idea of ‘uncertainty’ in playwork can be traced back to the nineteenth-century play clubs and the adventure playground movement. This suggests that playwork will continue to adapt to survive in the face of future uncertainty.

Works Cited

Allen of Hurtwood, Lady Marjorie. 1968. Planning for Play (London: Thames and Hudson)

Benjamin, Joe. 1961. In Search of Adventure: A Study of the Junk Playground (London: National Council of Social Service)

Bonel, Paul, and Jennie Lindon. 1996. Good Practice in Playwork (Cheltenham: Stanley Thornley)

Burghardt, Gordon M. 2005. The Genesis of Animal Play: Testing the Limit (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press)

Chan, Pauline, et al. 2020. ‘Playwork Play Works’, in Playwork Practice at the Margins, ed. by Jennifer Cartmel and Rick Worch (London: Routledge), pp. 39-56

Chilton, Tony. 2003. Adventure Playgrounds in the Twenty-First Century, in Playwork: Theory and Practice, ed. by Fraser Brown (Maidenhead: Open University Press), pp. 114-27

——. 2018. ‘Adventure Playgrounds: A Brief History’, in Aspects of Playwork, Play and Culture Studies, 14, ed. by Fraser Brown and Bob Hughes (London: Hamilton Books), pp. 157-78

Cranwell, Keith. 2003a. ‘Towards a History of Adventure Playgrounds 1931–2000’, in An Architecture of Play: A Survey of London’s Adventure Playgrounds, ed. by Nils Norman (London: Four Corners Books), pp. 17-26, https://www.play-scapes.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/Architecture-Of-Play1.pdf

——. 2003b. ‘Towards Playwork: An Historical Introduction to Children’s Out-of-school Play Organisations in London (1860-1940)’, in Playwork: Theory and Practice, ed. by Fraser Brown (Maidenhead: Open University Press), pp. 32-47

Department for Education. 2020. Guidance: Critical Workers and Vulnerable Children Who Can Access Schools or Educational Settings, 19 March, https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/coronavirus-covid-19-maintaining-educational-provision

Department for Education and Employment. 1998. Meeting the Childcare Challenge: Green Paper (London: HMSO)

Dickson, Annabelle. 2020. ‘Boris Johnson Announces Coronavirus Lockdown in UK’, Politico, 23 March, https://www.politico.eu/article/boris-johnson-announces-coronavirus-lockdown-in-uk/

Education Extra. 1997. Out of School Childcare Initiative: Succeeding Out of School (London: Department for Education and Employment)

Holmes, Anthea, and Peter Massie. 1970. Children’s Play: A Study of Needs and Opportunities (London: Michael Joseph)

Hughes, Bob. 1975. Notes for Adventure Playworkers (London: CYAG Publications)

King, Pete. 2015. ‘The Possible Futures for Playwork Project: A Thematic Analysis’, Journal of Playwork Practice, 2: 143–56, https://doi.org/10.1332/205316215X14762005141752

——. 2020. ‘Can Playwork Have a Key Working Role?’ International Journal of Playwork Practice, 1, https://doi.org/10.25035/ijpp.01.01.07

——. 2021a. ‘How Have Adventure Playgrounds in the United Kingdom Adapted Post-March Lockdown in 2020?’ International Journal of Playwork Practice, 2, https://doi.org/10.25035/ijpp.02.01.05

——. 2021b. ‘How Have After-school Clubs Adapted in the United Kingdom Post-March Lockdown?’ Journal of Childhood, Education and Society, 2: 106-16, https://doi.org/10.37291/2717638X.202122100

——. 2021c. ‘The Impact of Covid-19 on Playwork Practice’, Child Care in Practice, https://doi.org/10.1080/13575279.2020.1860904

——. 2021d. ‘Well-being Playworkers in Primary School: A Headteacher’s Perspective’, Education 3-13, https://doi.org/10.1080/03004279.2021.1971276

King, Pete, and Shelly Newstead. 2020. ‘Demographic Data and Barriers to Professionalisation in Playwork’, Journal of Vocational Education and Training, 73: 591-604, https://doi.org/10.1080/13636820.2020.1744694

Lambie-Mumford, Hannah, and Mark A. Green. 2015 ‘Austerity, Welfare Reform and the Rising Use of Food Banks by Children in England and Wales’, Area, 49: 273-79, https://doi.org/10.1111/area.12233

Lambert, Jack, and Jenny Pearson. 1974. Adventure Playgrounds (Harmondsworth: Penguin)

Mohajan, Haradhan K. 2017. ‘Roles of Communities of Practice for the Development of the Society’, Journal of Economic Development, Environment and People, 6.3: 27-46

Newstead, Shelly, and Pete King. 2021. ‘What Is the Purpose of Playwork?’ Child Care in Practice, https://doi.org/

Norman, Nils. 2003. Introduction to An Architecture of Play: A Survey of London’s Adventure Playgrounds, ed. by Nils Norman (London: Four Corners Books), pp. 7-16, https://www.play-scapes.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/Architecture-Of-Play1.pdf

Office for National Statistics. 2021. Childcare Providers in Regions of the United Kingdom, https://www.ons.gov.uk/file?uri=/businessindustryandtrade/business/activitysizeandlocation/adhocs/005704childcareprovidersinregionsoftheunitedkingdom/ah009.xls

Patte, Michael. 2018. ‘Playwork in America: Past, Current and Future Trends’, in Aspects of Playwork: Play and Culture Studies, Volume 14, ed. by Fraser Brown and Bob Hughes (New York: Hamilton Books), pp. 63-78

Play England. 2017. Adventure Playgrounds: The Essential Elements [Updated Briefing], https://www.playengland.org.uk/s/Adventure-Playgrounds-gph4.pdf

Playwork Principles Scrutiny Group. 2005. The Playwork Principles, https://playwales.org.uk/login/uploaded/documents/Playwork%20Principles/playwork%20principles.pdf

Pope, Thomas, and Eleanor Shearer. 2021. The Coronavirus Job Retention Scheme: How Successful Has the Furlough Scheme Been and What Should Happen Next? (Institute for Government), https://www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/sites/default/files/publications/coronavirus-job-retention-scheme-success.pdf

Public Health England. 2020. ‘Guidance: How to Stop the Spread of Coronavirus (COVID-19), https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/coronavirus-covid-19-meeting-with-others-safely-social-distancing/coronavirus-covid-19-meeting-with-others-safely-social-distancing

Rappaport, Helen. 2001. Encyclopedia of Women Social Reformers, I (Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO)

van Rooijen, Martin. 2021. ‘Developing a Playwork Perspective from Dutch Research Experience’, in Further Perspectives on Researching Play from a Playwork Perspective: Process, Playfulness, Rights-Based and Critical Reflection, ed. by Pete King and Shelly Newstead (London: Routledge), pp. 58-78

Saunderson, Ian, et al. 1995. The Out-of-School Childcare Grant Initiative: An Interim Evaluation (Leeds: Leeds Metropolitan University)

Shier, Harry. 1984. Adventure Playgrounds: An Introduction (London: National Playing Fields Association)

SkillsActive. 2010. SkillsActive UK Play and Playwork Education and Skills Strategy 2011–2016 (London: SkillsActive)

Smith, Fiona, and John Barker. 2000. ‘Contested Spaces: Children’s Experiences of Out-of-School Care in England and Wales’, Area 33: 169-76, https://doi.org/10.1177/0907568200007003005

Sturrock, Gordon, and Perry Else. 2007 [1998]. ‘The Playground as Therapeutic Space: Playwork as Healing (known as “The Colorado Paper”)’, in Therapeutic Playwork Reader One, ed. by Perry Else and Gordon Sturrock (Southampton: Common Threads), pp. 73-104

Trevelyan, Janet P. 1920. Evening Play Centres for Children (London: Methuen)

Voce, Adrian. 2015. Policy for Play: Responding to Children’s Forgotten Right (Bristol: Policy Press)

Waters, Philip. 2018. ‘Playing at Research: Playfulness as a Form of Knowing and Being in Research with Children’, in Researching Play from a Playwork Perspective, ed. by Pete King and Shelly Newstead (London: Routledge), pp. 73-89

Welsh Government. 2016. National Minimum Standards for Regulated Childcare for Children up to the Age of 12 Years, https://careinspectorate.wales/sites/default/files/2018-01/160411regchildcareen.pdf