6. Playworkers’ Experiences, Children’s Rights and Covid-19: A Case Study of Kodomo Yume Park, Japan1

© 2023, Mitsunari Terada et al., CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0326.06

Children in Japan during Covid-19

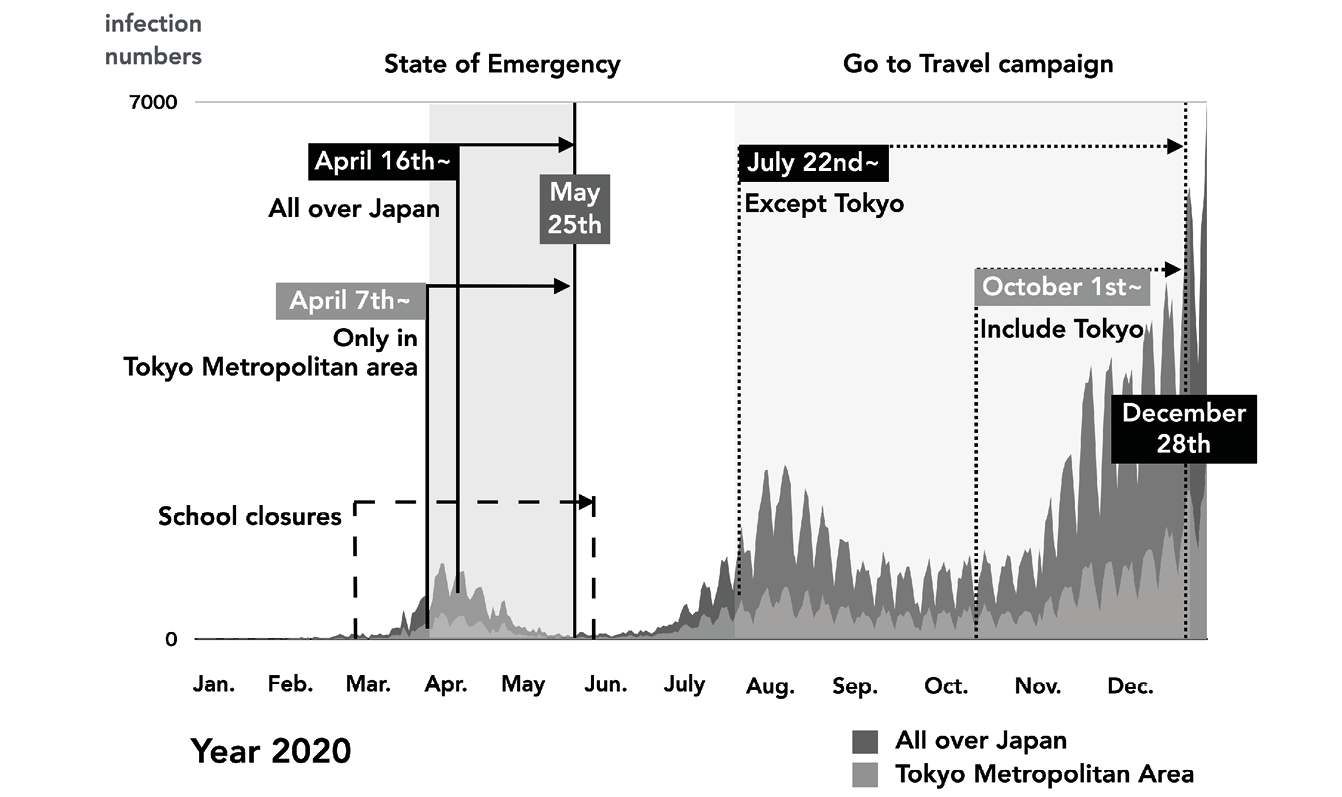

The Japanese fiscal year ends in March and begins in April. During this time people are busy moving, submitting tax reports, renewing contracts and documents, and graduating and starting school. When Covid-19 struck, all of Japan’s schools closed. Many graduation ceremonies were cancelled or moved online, and the new year began in confusion. Club activities and private lessons were also cancelled. From April 2020, the first state of emergency was announced (see Figure 6.1). Shopping centres and amusement parks were all closed. The number of infected people was low so, in July 2020, the government launched the ‘Go to Travel’ campaign to promote domestic tourism. However, this led to the subsequent spread of Covid-19.

During the Covid-19 pandemic, Japan was characterized by unique phenomena: despite the low number of official restrictions and ‘hard’ measures, the population exhibited high compliance with the recommendations to stay home, avoiding the ‘three C’s’—closed spaces, crowded places and close-contact settings. This high-level compliance was due to peer pressure in Japanese society, which means that stigma is attached to those who break rules and behave egotistically in ways that compromise the community’s safety. Violators of rules, condemned by the community, attract strong verbal and nonverbal feedback—looks, questions, threats, attitudes and even physical actions (attacks on property, etc.). During the pandemic, the phenomenon of the ‘self-restraint police’ (jishuku keisatsu) emerged, whereby community members would spy on one another to ensure that everyone was adhering to the safety regulations and would punish those who did not comply with them (Katafuchi, Kenichi and Managi 2021: 71). The phenomenon resulted in several suicides by those infected with Covid-19 because the infected individuals could not face the resulting social condemnation. Therefore, adherence to the restrictions ensured the containment of Covid-19 in Japan, but it also had very negative consequences. This specific cultural phenomenon of peer pressure also affected children’s welfare.

Figure 6.1 Timeline of Covid-19 in Japan, 2020 (based on data from Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, Japan)

Created by Mitsunari Terada, CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

Play comes naturally to growing children. They cannot fully control their body movements, voice, or energy. Children and caregivers during the pandemic were constantly under pressure from two sides: first, their neighbours and family members who, working at home, complained about noise from children (many apartments are poorly soundproofed) and second, the wider community complained about ‘children going out’ and playing freely despite the recommendation to stay home, thereby exacerbating the spread of Covid-19. Children and their caregivers did not have a place in which to simply be: the children’s need to play and move was ignored by adults who found themselves in high-pressure situations. This is reflected in the number of domestic violence reports, which increased during the pandemic, as well as the increased suicide rate among women (the main caregivers) and schoolchildren. The female suicide rate reached unprecedented levels, surpassing the male suicide rate for the first time in many years (Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare et al. 2021: 9). This has also been linked to job losses, as women hold the majority of temporary insecure positions and service jobs.

Japan’s National Centre for Child Health and Development conducted a survey on how children perceived the changes associated with Covid-19. Japan’s Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare reported that suicides among students, including those in elementary and junior high schools, reached 1039 in 2020, the highest since the government began compiling data on suicides in 1978 (Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare et al. 2021: 9).

The ‘National Online Survey of Children’s Well-being during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Japan’ offers a snapshot of children’s and caregivers’ situations (National Centre for Child Health and Development 2021): ‘Can’t meet friends’ (76%) was listed as the top concern among schoolchildren during the ‘stay at home’ mandate in the first wave of Covid-19, followed by ‘Can’t go to school’ (63%), ‘Can’t play outside’ (54%) and ‘Worried about study’ (52%). At least thirty-nine percent of children reported that they ‘[hadn’t] kept in contact with friends’, and screen time increased by seventy-two percent compared to the previous year.

Regarding stigma relating to Covid-19 infection, sixty-three percent of children agreed that ‘I want to keep it a secret if my family were to catch Covid-19’. Several pages of the report are devoted to gathering children’s direct voices. Children spoke about the unfair attitudes of adults regarding their needs: ‘Why are adults allowed to gather in large groups? A stranger got angry with us when we were playing’ (a seven-year-old boy). A twelve-year-old girl said ‘Do not treat us like germs/virus’, likely referring to adults’ attitudes towards children in public spaces. Another girl wrote in her response, ‘To my teacher: You give us too much homework. Also, seven periods a day are too much’ (National Centre for Child Health and Development 2021). Many children wrote that they wanted their opinions to be heard. Parents and teachers seemed too busy and children lacked one-on-one time. For example, a seventh-grade boy (between twelve and thirteen years old) wrote, ‘I want my teachers to listen to me in a room where I feel safe to talk to them and not be heard by other students’, and ‘It’s not easy to ask for advice. I need someone to help me do that’ (a fourth-grade girl, between nine and ten years old). The guardians’ responses revealed that twenty-nine percent of caregivers have moderate to severe depressive symptoms (National Centre for Child Health and Development 2021). During Covid-19, while children obviously had plenty of time to play, they did not always have a suitable space in which to do so. They felt lonely and perceived the adults’ nervousness as well as worrying about ‘falling behind in their study at school’ (Terada and Shimamura 2020).

The information presented above demonstrates that many children in Japan need a safe place in which to play and the opportunity to communicate with someone who will listen. When the pandemic separated them from their friends, they urged their parents to work harder and to care about the opinions of others. Providing a place for children to visit, and in which to play and communicate with others was an objective that kept Yume Park open when Covid-19 struck. In this chapter, we will discuss the decision to keep Yume Park open for children, safeguarding their right to play despite government restrictions and regional preventive measures, and how this was made possible through the efforts of the playworkers who accommodated visitors to the park.

Our aims are as follows:

- to investigate how children’s play and participation changed during the Covid-19 restrictions in the outdoor space of Yume Park

- to examine how playworkers adjusted the park’s usual policies in response to the emergency.

Data Acquired

The authors interviewed managers and playworkers in their twenties and thirties, while writing memos, during a three-day visit to Yume Park. Playworkers were interviewed in groups of three or four people. A group interview format was chosen in order to stimulate conversation and help playworkers to remember the events of 2020. A timeline of events was reconstructed in an interview with Daisuke Tomokane, current manager of the Yume Park facility. To prepare questions for interviews, we were advised by Yume Park leaders to look through the documentary created by one of Yume Park’s fans as the pandemic unfolded. A professional filmmaker, working on a voluntary basis, captured segments of playworkers’ meetings and interviewed a few of the parents visiting the park, and posted them on his company’s YouTube channel, Group Gendai.

The data therefore consists of the following: interviews conducted by the authors in early 2022; official statistics on visitor numbers collected by playworkers between March and August 2020, and augmented by a documentary on Yume Park (Group Gendai 2021); newspaper articles, and research articles. The park values its visitors’ privacy highly, and so we were not granted access to diary entries containing personal data. The study was conducted with the ethical approval of the leader of NPO Tamariba, which manages Kodomo Yume Park facilities and Kawasaki City office. All playworkers were interviewed with their informed consent.

Kodomo Yume Park, Kawasaki City

Historical Background

Kodomo Yume Park (henceforth Yume Park), translated from Japanese as ‘Children’s Dream Park’, is a youth centre complex that ensures children’s freedoms, allowing children from different backgrounds to play together in a safe environment. It was established in Kawasaki City in 2003 in accordance with Japan’s first local ordinance on children’s rights, an interpretation of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC) following the Japanese government’s ratification of the latter (Kinoshita 2007: 270).

The facility, founded and owned by Kawasaki City, is managed by the NPO [Non-Profit Organization], Tamariba. It aims to provide a space in which children may play freely, a place in which to be—ibasho (Tanaka 2021: 7)—and an alternative education system in which each child receives individual attention, in contrast to standard schools in which children differing from the norm may be ‘left behind’.

Hiroyuki Nishino, the director of Yume Park, was one of the first educators to voice concerns about children’s rights in Japan. Based on Articles 28 and 31 of the UN CRC, he pursued the idea of creating a third space in which children could play freely and receive education. He favours an approach wherein the initiative comes from the child, or at least wherein adults do not attempt to impose ‘programmed’ activities on to children, but rather to support children in their natural drive to play. The alienation and isolation reported by Japanese children in a UNICEF survey (Nagata 2016: 243) raised concerns among educational professionals. Nishino’s approach is characterized by chaos and diversity: ‘It is important to mix the people, abled and not abled, all different—we are all learning from each other’.

Kawasaki has a reputation for teen violence, with several cases attaining prominence in the media during the last decade. The city owes its diverse population to its industrial past and its foreign labour force. Disparities are extreme here: on the edge of Tokyo, the mingling of middle-class families’ offspring and children from socially vulnerable families (e.g. children of single parents, sometimes foreigners) create an environment that is particularly conducive to bullying (ijime) and exclusion. The problem is likely rooted in the Japanese education system, wherein children’s time is strictly regulated by adults: students spend all day at school with lessons in the morning and club activities (bukatsu) in the evening. Schoolchildren thus experience only two places: home and school. Occasionally, some children’s home environments are unsafe or poor (for example, their parents or single parent may work all day, have substance abuse problems or mental health issues, etc.). School would ideally offer such children a safe space, but on the contrary they are often bullied or ignored at school for being ‘weird’. Where might these children find a third space exempt from strict school rules and domestic issues?

To further compound the problem, the culture of groupism occasionally reaches the point of absurdity in Japanese public schools, as seen in certain high-profile court cases involving teachers who forced children to dye their natural brown hair black to promote conformity.

Yume Park was created in response to these issues and to accommodate any child in need, or those who do not wish to attend public school for whatever reason. Yume Park’s open space approach for children has been referred to as ‘free school’ by various publications. It does indeed provide children with graduate certification without attendance at formal educational facilities. However, Nishino prefers to call it ‘En’—a ‘free space’ rather than ‘free school’—to appeal to children who prefer to think that they are not attending a place called ‘school’.

‘In “Free Space En”, we are creating living space, going shopping, cooking, cleaning. Then, as we spend time together, we learn more about each other and nurture close relationships’, says director Nishino.

‘“It is nice that you were born, it is nice to see you here, I am glad to know you” is the message we need to transfer to children every day so that they flourish like flowers’, he concludes, asserting that Yume Park’s mission is the recognition of each person as valuable and worthy, simply by virtue of their existence in this world.

Facilities and Organisation

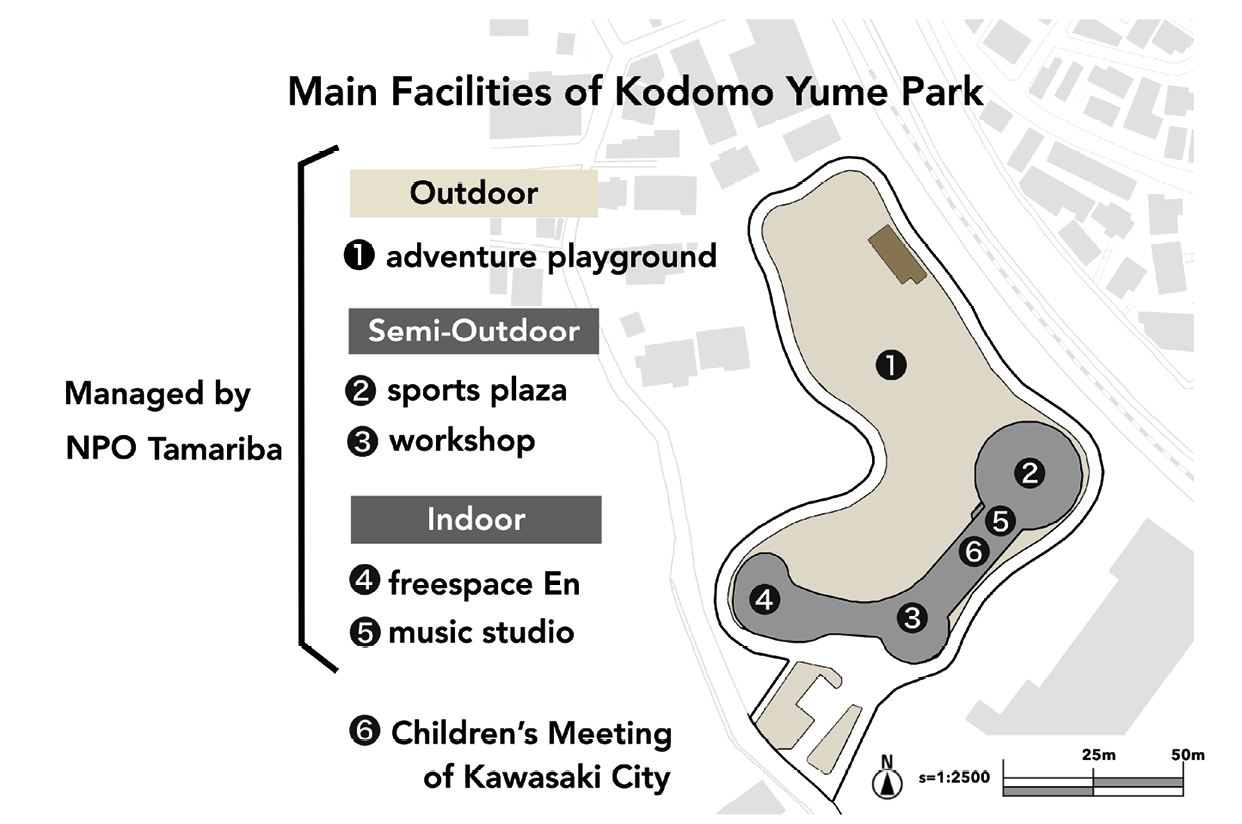

Yume Park’s facilities are described below (see Figure 6.2).

Figure 6.2 Main facilities of Yume Park mentioned in this chapter

Created by Mitsunari Terada, CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

Outdoor

1. Adventure playground. The outdoor space in Yume Park includes a small garden, lots for growing vegetables and parking spaces, etc. as well as one of the biggest adventure playgrounds within the urban sprawl of Tokyo’s megalopolis. The adventure playground is equipped with hand-made slides, swings and towers, water pools and mountains of clay-like soil (see Figure 6.3). Various tools and materials, such as hammers, nails, saws, wheelbarrows and lumber, are provided. Playworkers are available to help the children should they need it.

Figure 6.3 Scenery of adventure playground in Yume Park before Covid-19

Photo by Hitoshi Shimamura, CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

2. The sports area is a semi-covered concrete hall (with baskets, gates, a flat floor for ball games, etc.)

Indoor

3. Free Space En is managed by NPO Tamariba, an alternative education facility and free school which children attend instead of regular school, a so-called ibasho (Tanaka 2021: 7).

4. Music studio

5. Kawasaki City children’s meeting room

There is also a garden and farmland on the outside and multiple rooms available for rent and use.

From here on, we will use the umbrella term ‘Yume Park’ to refer to the entire facility.

Management and Children’s Participation Rules in Yume Park

A banner at Yume Park bears the message ‘No prohibitions’. Children are encouraged to do whatever they like provided that they do not harm themselves or others. No strict rules are universally applied in Yume Park, but rather rules are created within relationships and situations, and negotiated by participants within those situations. The interviews with the playworkers highlighted that people always question the reasoning behind newly established rules and form a habit of critical thinking, rather than blindly accepting the opinions of others. For example, if one group is playing ball games while younger children also wish to use the space, the older children understand that they must accommodate smaller children.

The Playworker’s Role Includes Facilitating Children’s Participation

Playworkers perform the facilitating role in the adventure playground. They are involved in the day-to-day management as well as event planning and preparation. They welcome visitors and make them feel at home in addition to stimulating the children’s play. As Nishino mentioned, children do not always express themselves verbally, therefore non-verbal communication can be considered participation too. Therefore, children’s play in Yume Park is any act of participation.

At least once a day, playworkers attend reflection and planning meetings, where they discuss the children’s condition, equipment maintenance and risk management. These meetings are sometimes held indoors in the ‘staff only’ rooms, but more frequently outside, so that the children do not miss the opportunity to participate in them (see Figure 6.4). The interviews suggest that this ‘flexible’ system is taken as a given, with no formal guidelines recommending that they ‘include the children’s voices, which would make it necessary to hold the meetings outdoors’. These participatory meetings were described as occurring naturally, when appropriate, or even spontaneously. The general culture of Yume Park (as a facility committed to the Convention on the Rights of the Child) involves close communication to understand children’s needs, and assistance in needs fulfilment by all employees.

The playworkers’ routine at Yume Park also includes daily journal entries about the day’s occurrences. This system was designed to keep all playworkers working various shifts informed and to facilitate continuity in communication with the children. For example, if Playworker A worked on Monday and learned something important about a child’s personal life, feelings and challenges, they could record it in the journal so that Playworker B, working on Tuesday, would be informed about the context. This system ensures continuous support for the children who visit Yume Park on a regular basis. This ‘diary’ allows the playworkers to record the joys and burdens of the day on paper, thus clearing their minds, as well as allowing them to communicate indirectly with one another.

Figure 6.4 Daily reflections of playworkers outside; children join naturally

Photo courtesy of Kawasaki Kodomo Yume Park, CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

Although the Yume Park facility is a designated children’s space, it is managed mainly by adults. However, children are considered among the facility’s stakeholders, and are invited to express their opinions on various issues and to manage spaces. It thus appears that children’s participation can be facilitated when adults can provide adequate risk management and a safe environment. One of the main roles carried out by the playworkers is risk management: they eliminate hazards and provide a safe space for children’s free play. Children can manage risks by themselves; however, hazards (unexpected physical dangers above a certain threat level) must be removed.

However, when adults do not know how to ensure safety, it becomes difficult to create a space suitable for children’s play. The director, Nishino, said that Covid-19 offered an opportunity to renew relationships between adults and children because neither group had pandemic experience, and both ‘stood at the zero level’. Some might disagree, arguing that adults lost the psychological confidence required to manage the situation, including their primary role of ensuring safety. However, Nishino likely sought to interpret the negative situation in a positive light in a bid to keep spirits high during difficult times and to try to frame the crisis as an opportunity for people to become closer to one another.

In the next section, to contextualize Yume Park’s achievement in protecting the child’s right to play, we will first offer an overview of Japan’s Covid-19 timeline and the local government’s response, before characterizing children’s play and the general circumstances of Japanese society during the pandemic.

Reflections on Yume Park’s Actions to Ensure Freedom of Play

Our contribution focuses on the beginning of the pandemic (March to August 2020), when there was general confusion around how to perform usual activities within a Covid framework. The absence of a clear understanding of how to behave is of the greatest interest in our analysis. Therefore, we have not described autumn 2020, when Yume Park implemented its annual festival or the period post-2021, when the situation stabilized.

Timeline of Actions in Yume Park

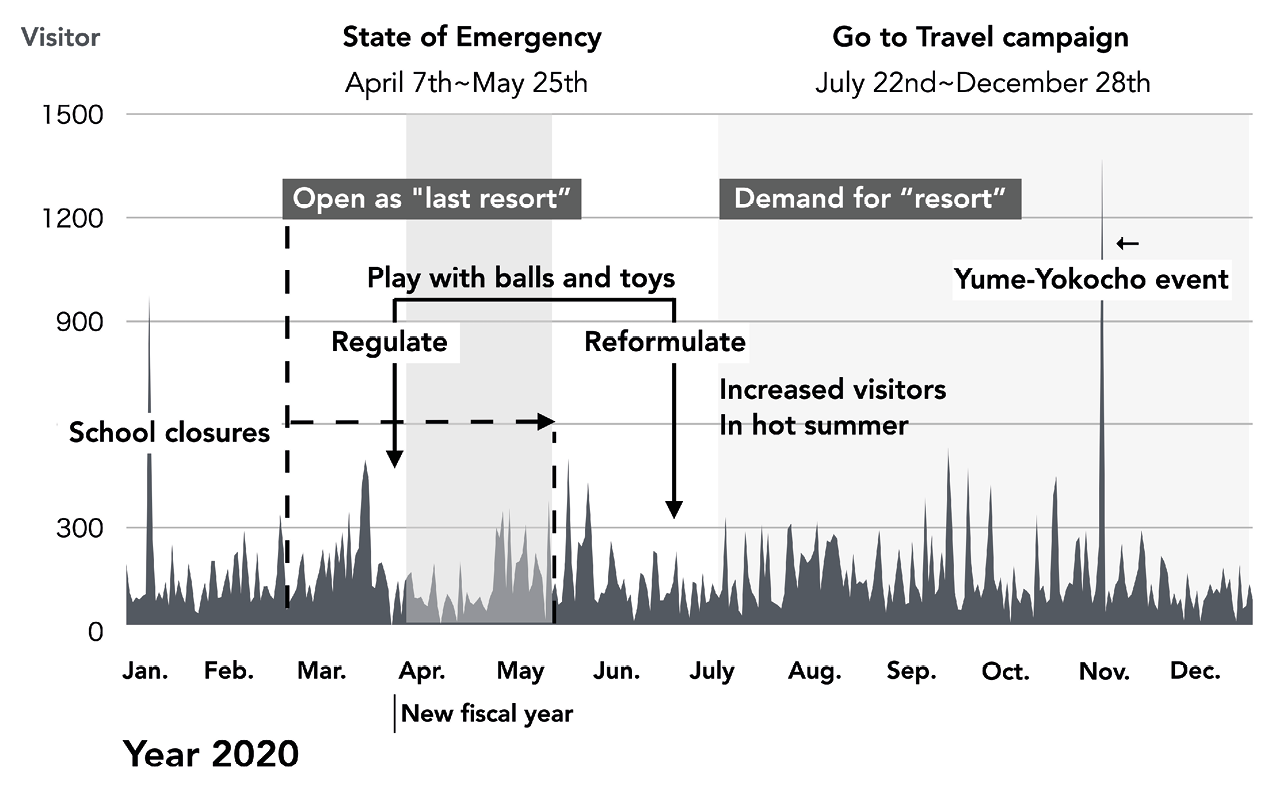

Figure 6.5 Timeline of Yume Park, 2020 (based on data from Kawasaki City)

Created by Mitsunari Terada, CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

At the beginning of March 2020 in Japan, the government imposed restrictions on activities in public facilities in a bid to curb the spread of Covid-19. The closure of public schools was among the first responses. Because Yume Park is a public facility, it too was under consideration for closure. Through the concerted effort of Yume Park representatives and city officers, the facility was kept open as a ‘last resort’ (see discussion topic A below), with several changes to its rules and functions as preventive measures (see discussion topics B, C and D below). This decision was based on an understanding of Yume Park’s importance as a place for Kawasaki’s most vulnerable children and families. Yume Park’s director also used various media—television, newspapers, social networks—to emphasize the importance of supporting children with such facilities during the pandemic. Under the first emergency call, the number of users declined compared to the usual figures, but some children continued to visit, as it was their ‘space’.

From the end of Golden Week—a series of holidays clustered and observed at the end of April and beginning of May in Japan—the number of visitors to Yume Park increased (see Figure 6.5). Once the school year started, the number of visitors stabilized. However, with the hot summer that followed and pandemic-related regulations—including the advice to stay home—people turned to Yume Park as an accessible recreational space. Playworkers perceived this tendency as a misuse of Yume Park, believing that it was being treated as a holiday ‘resort’. The playworkers were risking their lives supporting children’s play in the context of the stressful restrictions (see Section C below). Yume Park had to impose measures to prevent overcrowding and adjust its ethos accordingly (see Section D below).

Discussion of Topics Emerging from Interviews

The discussion that follows is based on four themes (A–D) that emerged from interviews with Yume Park’s playworkers and leaders.

A. Should Children’s Facilities Be Open for Play Rights in Uncertain Times?

As we mentioned in the introduction, many public facilities for children were closed, especially in the beginning of the pandemic in 2020. This is an understandable measure to avoid spread of infection. Within these circumstances, the attempt to ensure safety for all by imposing stay-at-home policies posed the risk that some children would become unsafe.

Therefore, Yume Park’s solution was to remain open to support children’s rights. This decision is also supported by the International Play Association, which underlines the importance of play in crisis as a coping mechanism (International Play Association 2020).

In March 2020, as Japan was formulating its emergency measures, Yume Park was preparing to keep its doors open. It was clear to Nishino that those children whose need for care and support was greatest might lose a place where they could go and talk. He argued that Yume Park should be kept open as ‘the last resort’ (saigo no toride—literally, ‘the last fortress’) in an interview with NHK, Japan’s public media channel, that was later quoted in newspapers (NHK 2021). Nishino understood that children and parents were facing a particularly difficult situation, and many caregivers told playworkers that Yume Park was the only place in which they felt safe. In the Group Gendai documentary, one mother told the camera, ‘The children wanted to play outside. They were quite aggressive, having to stay home, punching the walls. It was difficult’. Another female visitor told the camera, ‘The apartment owner told us off because we are so noisy as a family. It was difficult, so we decided to come to Yume Park from time to time. So if there were no place like this, that would be just unbearable’. Considering society’s failure to acknowledge children’s needs to play, to make noise and to simply be, whether in their apartments or outdoors, Yume Park offered a crucial source of support during the pandemic. Interviewees often mentioned ‘other people’s eyes’, which, in Japanese, means the attention and pressure from other community members.

Director Nishino pointed out in his interview,

Children usually cannot ask for help by words, so they give us signals by their body language—strange movements or irritation. So when the environment turns against children, as in the case of Covid restrictions, we had to keep the place open, in order for children to have a place to be. Because, as I said, children can’t ask for help or advice by words, usually, you know, so if they just have a place to be, where someone listens and pays attention to them, that’s the way to help them.

With this argument, he described his determination at the beginning of the pandemic in 2020 as follows:

At the end of February, when I heard that the government planned to close public schools, I went to the city office and spoke to the officers: ‘We need Yume Park open now more than ever before’. They understood. Because it was established in accordance with the Child’s Right to Play Article, they accepted my request.

Some playworkers were hesitant at the beginning of 2020, as the growing panic and uncertainty caused much confusion. Announcements (Japanese cities have speakers installed throughout them for such announcements in case of disasters) sounded daily, with the message urging citizens to ‘PLEASE STAY HOME’. However, learning directly from children and parents, the playworkers gradually acknowledged the need to keep Yume Park’s gates open:

During Covid times, children reported increased abuse from parents, and parenthood difficulties were reported by parents. We created a time and space for people to come and talk about these issues in their family—parents in trouble, children in trouble. There was a news report about a son who attacked a family with a knife, so it was very scary to hear.

Some playworkers shared Nishino’s determination from the outset.

The discussion about the necessity to keep Yume Park open relates closely to the following two themes: making new rules and the burden of working during the reality of a pandemic.

B. Controversy of Encouraging Interactive Play within Social Distance Requirements

During the pandemic, playworkers shouldered a heavy burden. First, they risked infection while working ‘in the field’ with visitors, and second, they were responsible for comforting the children. At the time, no one considered that the burden for playworkers might be too great. One of the playworkers reflected:

When the coronavirus struck, we all suddenly became more distant, because we had to keep our distance, as the officials recommended. We did not have experience of pandemic situations, so we relied on recommendations like wearing masks, not talking, keeping our distance. So, we found ourselves quite isolated—less personal communication took place between staff, and a kind of alienation developed.

Three of the playworkers interviewed had worked at the park for four years, while the others had worked there for ten and six years. Regardless of their age, they were experienced playworkers.

The most difficult aspect for playworkers was losing their role of encouraging children’s play:

I felt that I had lost my very essence, to support children’s play and encourage them—I could not do that. When I tried to speak to one visitor, she rolled her eyes at me—“What nonsense to speak in a pandemic!”—her face said to me. I was losing confidence in my role and the sense of meaning in being there.

It is clear that the playworkers experienced an identity crisis amid the anti-Covid measures, as their normal actions—facilitating communication between people and the environment—could cause transmission, spreading the virus among visitors. They were losing their role. Additionally, as the new school year began in April, it was difficult to establish relationships with the new children, with fewer opportunities for talk and interaction in the context of ‘social distancing’ (see Figure 6.6).

A playworker shared her thoughts about the stress of working during 2020:

I live with my elderly parents and take the train to work every day. So, every time I put my family’s lives at risk, not only in the park, meeting visitors, but also on the way home. It was hard, constantly being afraid of getting infected and passing it on to someone else.

Another playworker who had been working in Yume Park for ten years said:

At the time, I was so scared so I was thinking it would be good to get the coronavirus quickly—I hoped to get immunity and relief from being afraid.

Another male playworker also said that he feared becoming infected because he travelled to work on an overcrowded train.

A female playworker shared her concerns about childhoods in the pandemic:

Who will take the responsibility for these children growing up without touch? We were thinking together with the children, what is it to live? We thought about it, being just a heartbeat, but without relationships with people, is that a life?

During the interviews with playworkers, we discovered that they did not discuss their own feelings much during the most hectic times. Although they continued to record daily occurrences in the journals, they never discussed their own doubts, fears, and despondencies, likely due to the diary’s public nature and its informative function. The playworkers themselves only realized retrospectively that they were psychologically exhausted.

Figure 6.6 Children play on water slide in 2016 and in 2020 with social distancing

Photo courtesy of Kawasaki Kodomo Yume Park, CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

C. The Need for New Rules at Odds with the Usual Policy of Yume Park

Supporting children’s play rights, Yume Park succeeded in staying open with zero infection in the facility. As before the pandemic, children had a place to play. However, it was crucial that facility managers reacted quickly to ensure safety and to limit some play activities without negotiating new rules with children as they would usually do. Reasons for this were: time limitations, pressure from society (all other facilities were closed), uncertainty regarding the dynamics of the virus spread, and an urge to comply with governmental policies like the ‘state of emergency’.

During spring vacation and school closures, many schoolchildren from around the neighbourhood came to play ball games, as they used to do in public school at bukatsu—(club activities in Japanese schools, from bu, ‘club’ and katsu, ‘activity’). In many public parks, especially in the Tokyo metropolitan area, there is a high rate of ball game prohibition (Terada and Kinoshita 2020: 52). However, playworkers soon realized that the risk of spreading the virus was high with up to fifty children running close together and fighting for the ball. The playworkers’ struggle to impose prohibitions is evident in the following passage:

The junior high schoolers were coming to play basketball in big groups, and when I approached them to ask them not to play and explained that many people were touching the same ball and moving closely together, they asked me, ‘why then is it ok to use the carpenter’s tools in the adventure playground?’ I did not know how to resolve this issue, and I felt it was dangerous because the number of people infected was growing by the hour at this time and I was worried that we would have to close it [Yume Park] if a virus cluster occurred. And I strongly felt it was a place for people who have no other place to be, mostly, you know, for them we keep it open, and these claims from schoolchildren who wanted to play basketball were a little irritating to hear. I had to make judgements relying on my estimation and analysis. For example, today this child needs this the most, so it is OK to allow him/her to do this and that. We had to make many decisions every day, taking responsibility. We were constantly puzzled and troubled by the necessity to decide what was good and what was bad in each situation.

Of course, it would have been easier if everything had been definitively decided all at once. However, this is not how Yume Park works. As noted above, the rules in Yume Park are flexible, situated and bound up in relationships. Typically, they are changed and acknowledged based on negotiation and reasoning. However, during a pandemic, changes to rules must be implemented swiftly: from 4 April, visitors were no longer permitted to use balls and toys, whether rented or their own. Exceptionally in Yume Park’s history, rules were changing from day to day and these changes were implemented from the top down.

For playworkers, one of the key questions was ‘Can we accept that adults should determine the rules of children’s facilities to minimize the risk of Covid-19?’ One playworker spoke of early April, before the announcement of Japan’s national state of emergency on 7 April:

It seemed that there was no choice but to accept the ‘no balls, no toys’ policy, because a state of emergency would be announced soon. Should we have asked the children’s opinions, even though there was no possibility of changing the rules at that time?

At the time, playworkers still did not know how to enforce appropriate safety measures against the virus, so the strictest safety was necessary. Nonetheless, as play professionals, they thought constantly about how best to support children’s rights to play and participate.

Amid the regulations, children began creating new forms of play in spite of the limitations. For example, they made paper balls instead of using the prohibited basketballs or footballs. Soon, paper balls were also regulated, so children started balancing on the pipe to keep their distance from each other and touching the ball with a stick, etc.

During the first months of Covid-19, from March to May, rules were swiftly decided without the children’s participation. However, in June several factors led to their re-formulation. First, children were persistent in their desire to play and were constantly questioning the rules, seeking to compromise play and safety measures, and so a series of discussions between children and playworkers took place (see Figure 6.7). Second, Yume Park’s culture prioritizes children’s voices in deciding new rules. Owing to this culture of children’s participation in rulemaking, Yume Park reinstated the mechanism for constantly updating the rules regarding balls and toys, depending on the situation.

Figure 6.7 Children and playworkers reformulating the rules together in the adventure playground

Photo courtesy of Kawasaki Kodomo Yume Park, CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

D. Dealing with Conflict: When ‘Last Resort’ Turns into ‘Just a Resort’

From the end of July, with the arrival of the hot weather, playworkers observed a growing demand for outdoor play and increased visitor numbers. As a consequence of the prevalent shaming culture, many people travelled from other prefectures, trying to escape their neighbourhoods’ watchful eyes so that they could enjoy outdoor play secretly. Others turned to Yume Park because other recreational facilities were closed, and travelling by train or plane was considered a step too far. More and more people came to have ‘picnics’, as Yume Park was officially open and welcoming visitors as a self-proclaimed ‘last resort’, whereas local Tokyo parks still advised that people refrain from visiting.

It seemed to the playworkers that Yume Park was being overused. First, huge visitor numbers prevented the formation of close relationships. Second, people’s lack of familiarity with the culture of the playground led to misunderstanding and stress on both sides: people behaved like customers in a shopping centre, asking for and ordering tools or playground features, for example. Yume Park was turning into a ‘resort’ in which a kaleidoscopic array of consumers needed to be served quickly and to their full satisfaction. Furthermore, the pandemic was not yet over and preventive measures, such as social distancing and mask wearing, were still in place.

This loss of human interaction in the adventure playground had been unpleasant but necessary. As a result, the playworkers created communication boards and duplicated the playground equipment. Signs were erected to explain the playground’s functions and rules, thereby avoiding direct communication so as to help prevent the spread of Covid. These signs reminded visitors not to eat, drink or picnic on the facility and to stay for no more than three hours at once. The duplication of playground equipment reduced the load on single structures and minimized the density of queues for each structure.

The various users had different situations: some had nowhere safe to be; others had no place to picnic and were bored at home. Everybody wanted to go outdoors and enjoy the opportunity to play freely. Demands for outdoor play should be satisfied accordingly but, in the case of Yume Park, the playworkers felt that the ‘last resort’ status was being ‘misused’. Playworkers, faced with the risk of Covid-19 infection, with up to seven hundred visitors per day, felt conflicted.

Conclusion

In this chapter we have shared Yume Park’s effort to remain open to ensure the fulfilment of children’s rights, focusing on the beginning of the pandemic in 2020 (approximately March to August). Currently, in 2022, Yume Park still has zero recorded cases of Covid-19 and successfully implemented annual events like Yume Yokocho Festival (where children create their own shops and sell products) in 2020 and 2021.

Current Yume Park director Tomokane said, ‘We don’t want to show the attitude that we cannot do things because of Covid; we want to show how we can do things, even in the pandemic. It is because children are living right now’. Play is about actively engaging with the world and creativity is about finding a way to do something. If adults find reasons to be passive because of Covid, children may as well lose hope.

School closures during lockdowns increased demand for outdoor play facilities and compelled Yume Park managers and playworkers to impose limitations and rules without the usual negotiation process during the first months of restrictions. They were then adjusted in response to the evolving situation, which enabled a re-negotiation with the children, in accordance with the facility’s human-centred culture. This was made possible thanks to the selfless efforts of the playworkers who, often neglecting their own psychological needs, continued to go to work and make decisions on the ground, within the framework of a roughly designated safety zone. Rules were developed with the children’s input based on foundational information about the virus, and measures, such as minimum social distancing between people or the need to sterilise one’s hands with alcohol, were incorporated into the park’s day-to-day running.

Covid-19 was a new challenge that forced adults to consider how they could support the child’s right to play in a new environment, for which the potential to apply previous experience was limited. The interviews with Yume Park’s managers and playworkers revealed that the park’s staff have a strong sense of its identity, support children’s rights, and are willing to endure hardship in pursuit of this mission. This was made possible through daily meetings, reflections, and discussions, in a practice and culture that had been applied and nurtured for almost two decades. The Covid emergency confirmed that a strategy that may previously be seen as highly idealistic was in fact useful when a pandemic required people to reflect and adapt regularly.

Works Cited

Group Gendai. 2021. Documentary Series about Yume Park during Pandemic, https://youtu.be/j9gRT9A_s-0

Katafuchi, Yuya, Kenichi Kurita, and Managi Shunsuke. 2021. ‘COVID-19 with Stigma: Theory and Evidence from Mobility Data’, Economics of Disasters and Climate Change, 5: 71–95, https://doi.org/10.1007/s41885-020-00077-w

Kinoshita, Isami. 2007. ‘Children’s Participation in Japan: An Overview of Municipal Strategies and Citizen Movements’, Children, Youth and Environments, 17: 269-86

Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare of Japan and others. 2021. Suicide Situation in 2020, https://www.mhlw.go.jp/content/R2kakutei-01.pdf

Nagata, Yoshiyuki. 2016. ‘Fostering Alternative Education in Society: The Caring Communities of “Children’s Dream Park” and “Free Space En” in Japan’, in The Palgrave International Handbook of Alternative Education, ed. Helen E. Lees and Nel Noddings (London: Palgrave Macmillan), pp. 241-56

National Centre for Child Health and Development. 2021. National Online Survey of Children’s Well-being During the COVID-19 Pandemic in Japan, https://www.ncchd.go.jp/center/activity/covid19_kodomo/report/digestreport_en.html

NHK [Japan Broadcasting Corporation]. 2021. Children’s Dream Park: About Children Who Do Not Attend School, https://www.nhk.or.jp/shutoken/yokohama/article/000/66/

International Play Association, 2020. Play in Crisis, https://ipaworld.org/resources/for-parents-and-carers-play-in-crisis/

Tanaka, Haruhiko. 2021. ‘Development of the Ibasho Concept in Japanese Education and Youth Work: Ibasho as a Place of Refuge and Empowerment for Excluded People’, Educational Studies in Japan, 15: 3-15, https://doi.org/10.7571/esjkyoiku.15.3

Terada, Mitsunari, and Isami Kinoshita. 2020. ‘Research on Local Governmental Restrictions for Ball Play in Block Parks’, Landscape Research Japan Online, 13: 52–58, https://doi.org/10.5632/jilaonline.13.52

Terada, Mitsunari, and Hitoshi Shimamura. 2020. ‘Finally Got Free Time? Could Public Spaces Reverse Children’s Play-Deficit in Post-Pandemic Japan?’ Unpublished conference paper presented at the ‘IPA-World Play and Public Place Seminar, 4: State of Play in Cities’

1 We would like to thank the Yume Park manager Daisuke Tomokane, the Director of NPO Tamariba Nishino Hiroyuki, and the playworkers who made it possible to organize interviews and investigate activities in Yume Park during Covid-19. This work was supported by the Japanese Society for the Promotion of Science KAKENHI Grant Number 22K14912.