‘Cough’

Drawing on schoolyard fence, Philadelphia, 1 July 2021

Photo by Anna Beresin, CC BY-NC 4.0

7. Objects of Resilience: Plush Perspectives on Pandemic Toy Play1

© 2023, Katriina Heljakka, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0326.07

Introduction

‘Objects embody unique information about the nature of man in society’, writes Susan Pearce (1994: 125). Relations with material things have powerful consequences for human experience, as objects serve to express dynamic processes within people, and between people and the total environment (Csikszentmihalyi and Rochberg-Halton 1981). All three-dimensional objects are active instruments of communication, and in particular of non-verbal communication (Volonté 2010).

During a certain age in the child’s development, ‘artefacts become its principal means of articulating feelings and desires’ (Miller 1987: 99). Following Piaget’s idea of thinking with and through objects is a feature of childhood that adults abandon (Eberle 2009). Nevertheless, from infancy onwards, we are not only touching objects but are also being touched by objects.

This chapter takes an interest in the role of soft toys and meaning making in relation to them in play during the Covid-19 health crisis. Toys are the material artefacts of play. However, toys, Rossie explains, are frequently described as objects and not as instruments of play. For this reason, the play activity is not analyzed with the same care as the toy itself (Rossie 2005). The chapter at hand takes an interest in how plush toys have been used in play during the ongoing pandemic and attempts to analyze the play patterns and player motivations with the same care given to the toys under scrutiny.

To ‘play with’ an object is to experience the satisfaction of trying to control it (Henricks 2006). Sometimes playing with toys extends beyond the physical manipulation and control of objects into the meanings created and communicated about human matters. Earlier work suggests how concepts such as play value and toy play experiences can be analyzed. First, toys as designed objects may accrue meanings and play value in terms of their aesthetics, ergonomics of use, age appropriateness, durability, safety, educational affordances and entertainment value (Heljakka 2013). Second, experiences in relation to toys, and toy play in particular, may be structured by using a framework with physical, functional, fictive and affective dimensions (Paavilainen and Heljakka 2018). Contemporary toys as three-dimensional, material playthings may in other words be considered as physical entities that can be manipulated in terms of object play. Usually, the toys are functional in terms of both their playability—they are intended to be used in play of some kind and afford, for example, possibilities to pose and display them in different ways. Toys of the contemporary kind often also include a fictional aspect—they may due to their personality as character toys have a backstory of some kind. In the simplest sense, they may have a name and a personality described in a few sentences. On the other hand, they can be tied to transmedia franchises or story worlds. Toys are also objects and vehicles which communicate emotions (Shillito 2011). Therefore, the toy play experience usually includes an affective component, which means that the player forms an emotional bond with the plaything. The study presented in this chapter demonstrates how all of the aforementioned dimensions of toy experiences are relevant, when considering their use in the context of play during the pandemic.

In Western societies, toys are mass-produced objects often tied to transmedia phenomena and popular storytelling. The chapter focuses on a universally recognized character toy with connections to news media and has long-standing roots in the history of toy making and play with plush toys—the teddy bear. The teddy bear is the world’s first mass-marketed toy (Leclerc 2008) and one of the most recognized and popular character toys universally. In 1998, the teddy bear was elected to the Strong National Museum of Play’s National Toy Hall of Fame (Strong Museum n.d.). The year 2002 was celebrated in North America, Europe and Asia as the hundredth birthday of the origin of the teddy bear (Varga 2009). At the time of writing this chapter, the teddy bear is celebrating its 120th birthday as one of the oldest transmedial toy phenomena.

The teddy bear and its ‘huggability’ results from a long evolution from the first, more ‘realistic’ bears marketed by toy makers Mitchom and Steiff in the early 1900s to ‘the teddy bears we came to know and love look more like cubs, rounded, wide-eyed, big-eared, stubby-limbed, and most important, needy’ (Eberle 2009: 74; for extensive research on the teddy bear’s origins and evolution, see Varga 2009). As discussed in this chapter, teddy bears and other ‘cutified’ plush suggest a need to be cuddled and nurtured but, as proposed in the chapter, also have the capacity to ‘give back’ by providing their human counterparts crucial playful support and a communicative means in times of crisis.

The Sensory, Sentimental and Survivalist Potentiality of Plush

The aim of this chapter is to deepen the understanding of object play during the beginning and continuation of the Covid-19 pandemic. By focusing on play patterns with soft toys or plush, as these toy characters are sometimes referred to in the North-American context, the author strives to form an understanding of the relevance of these toys for ‘pandemic toy play’ (Heljakka 2020).

Toys are most often associated with childhood and considered as suitable gifts for a child: ‘These small objects, pretty or ugly, clean or dirty, are a comfort to a child, often a best and closest friend’ (de Sarigny 1971: 6). As Fleming notes, ‘toys are infinitely adaptable and can take on meanings other than those they originally came with’ (1996: 67). Indeed, children have a way of doing things with toys over and beyond the apparent character of the toy (Sutton-Smith 1986). Toys can and do have dual function, one in the minds of adults and another in the culture of children (Chudacoff 2007).

What makes toys particularly valuable artefacts for the child is the fact that they may become transitional objects in the child’s relationship with its mother, relationships with the world of things and other people (Sutton-Smith 1986). Donald Winnicott (1896-1971) is one of the most influential theorists on object play. Winnicott’s conception of transitional objects highlights the psychological significance of the child’s early ‘not-me’ objects: for example, the attachment the child forms to a soft toy (Crozier 1994).

The transitional space between mother and child both connects and separates them. It is the ‘either-or’ or the ‘neither-nor’. Soft toys may help the child to move away from the mother by operating as substitutes for maternal presence. They are loved fiercely, and, in the strongest instances, never leave the child (Ivy 2010). What Winnicott notes about this relation between the human self and the material object is that it ‘establishes here an underdetermined space, a blur between fantasy and reality’ (Marks-Tarlow 2010: 43).

Doll designer Käthe Kruse maintained that the way to a child’s heart was not through the eyes in the form of a perfectly miniaturized doll, but through its hands in the shape of a soft toy (Reinelt 1988). According to ‘Dr Toy’, Stevanne Auerbach, the ideal toy relationship is ‘that the child not only enjoys it from the beginning, but they want to go back to the toy, that they get attached to it, a teddy bear’ (Heljakka 2013: 175).

Long-term relationships with toys are formed with those characters that communicate vulnerability and call out for nurturing and care: ‘[soft toy animals,] in so far as they are humanized, in the sense of being endowed by a child and parents with human qualities, including the ability to ‘look back’, to communicate and to receive communications, they share the function of companion and friend, protector and protected’ (Newson and Newson 1979: 90). Moreover, stuffed toy animals are stimulating, visual and material playthings. The connection between the player and the plush can be soothing. In play with soft toys the sensory stimuli extend to emotional attachment between the player and the toy. In this way, plush toys function as a source of communication (Auerbach 2004).

Earlier literature on teddy bears acknowledges them as ‘ambassadors of love’, which have evolved from being a mother substitute to an adult fetish, an item of adult idolatry resulting from commercial nostalgic production of the teddies in the post-1950s (Varga 2009: 72; 76). These soft toys especially may, in their players’ hands and minds, turn into personalities, inanimate friends and quiet confidants who have their place on our shelves, sofas and even—in our hearts.

Ruckenstein (2011) proposes that toys could be thought of in terms of their potentiality. The goal of this chapter is to investigate how this potentiality materializes in plush characters which often represent commercial playthings. Cook describes how commercial objects are believed to retain ‘some kind of taint that renders inauthentic most any practice associated with it. […] It is artificial because it was borne of, and exists in the realm of commercial goods and commodity production’ (2009: 90). Nevertheless, Belk has noted how even contemporary mass-produced objects may be thought to have ‘magical’ properties, from the capacity to protect their owners from harm to the capacity to cure, empower and bring good luck (Belk 1991; cf. Crozier 1994). The potentiality of toys manifests on one level in their supposed ‘liveliness’, achieved through animism and the human tendency to anthropomorphize.

Animism, the belief that objects, animals and plants have spiritual lives of their own, connects with the idea of bringing toys to life. In this tradition of thinking, objects are given agency so that the manipulable object is believed to encompass supernatural qualities. Again, anthropomorphizing refers to the tendency of attributing a human form or personality to things that are not human. Humans are predisposed to anthropomorphize, to project human emotions and beliefs on to anything (Norman 2004). In terms of relationships with toys, this tendency to ‘animate the inanimate’ is also visible in adult toy play (Heljakka 2013).

Anthropomorphization is extended to all sorts of objects: ‘the toys that emerge from the toy cupboard are all granted mobility, feelings, and desires’ (Kuznets 1994: 144). Karl Groos writes in the Play of Man, ‘the child playing with the doll raises the lifeless thing temporarily to a place of a symbol of life. He lends the doll his own soul whenever he answers a question for it: he lends to it his feelings, conceptions and aspirations’ (Groos and Baldwin 2010 [1901]: 203).

Plush toys tend to attract players of many ages. Toy types such as traditional, animal-themed soft toys, and toy characters that lean on the fantastic in their aesthetics, seem to cater best to the request for gender-neutrality (Heljakka 2013). The popularity of teddy bears is not limited by gender. Cross explains the allure of the teddy bear for wider audiences of players, including young males: ‘Unlike the doll, long linked with girls’ gender role-playing, the bear has had wild and primitive “boyish” associations, thus making it appropriate for male companionship’ (2004: 53). According to the survey conducted by the hotel chain Travelodge in Britain and Spain, a large number of ‘bear-toting travelers are men’. The hotel had, over twelve months, ‘reunited more than 75 000 bears with their owners’ (Mayerowitz 2010). The study conducted in Britain in 2010 revealed that twenty-five percent of the men who answered the survey said that they take their teddy bear away with them on business trips because it reminds them of home (Mayerowitz 2010).

Throughout the times when toys have been produced industrially, adults have used them as bribes, instruments for bonding and affection (Chudacoff 2007). Adult imagination in connection to character toys of the contemporary kind results often in relational interactions with the teddy bear toy (Varga 2009).

The teddy bear is considered an emotional plaything that brings comfort to its owner, no matter the age or gender of the player. Doll researcher Jaqueline Fulmer has discovered that there are many Americans who creatively express their identity through the medium of dolls (including soft toys like teddy bears) and that they constitute a thriving and diverse subculture with the potential of connecting people during a crisis (2009).

‘Why should children be the only ones to enjoy stuffed animals?’, Dr. Toy Stevanne Auerbach rightly asks (2004: 112). During the Covid-19 pandemic, teddy bears and other plush animals have illustrated the ability to bind people—children, adults and seniors—together during crisis. By introducing the #teddychallenge, the first goal of this chapter is to accentuate teddy bears’ potentiality as playthings with intergenerational appeal. The second is to illustrate how plush toys, in particular, continue to thrive as objects that channel a survivalist attitude—a theme of interest to past and present investigations of teddy bears.

‘Name a social, health or environmental disaster and the teddy follows’, Donna Varga aptly claims (2009: 81). Indeed, plush animals have been employed in both moments of collective mourning as well as deliberate trauma management, as for instance with trauma teddies, used in association with mass disasters in Australia during the devastating bushfires of 2019-2022. The idea of trauma teddies is that emergency personnel carry them around to give to children and adults who have experienced trauma.

To conquer despair, teddy bears have also been used to commemorate national tragedies, such as the car crash death of the United Kingdom’s Princess Diana (Varga 2009: 79, 81; Fulmer 2009: 92). In fact, Varga notes how the teddy is reified as a therapeutic artefact that is able to provide bearapy (2009: 72; 79). Cook positions the teddy bear as ‘a readily recognizable symbol of loss and object of comfort’ (2009: 89) which, according to Sturken, ‘make[s] us feel better about the way things are’ by its presence alone (2007: 7). In this way, teddies fill their function to serve humans in practical and existential ways—as comforters to hug and as bearers of hope to hold on to.

From allowing sensory and sentimental gratification, plush creatures move on to promote survival in the name of toy activism. Earlier work on serious uses of toys presents the possibility of using character toys in ‘toy activism’. Toy activism, as formulated by Heljakka, refers to harnessing character toys, such as dolls, action figures and animal characters, including various soft toys, to make visible or to promote a political, ethical or emphatic goal (2020, 2021).

Toy activism is not a new phenomenon. In the 1980s, giving teddy bears to AIDS sufferers was a means of extending contact in an indirect way to the forbidden bodies of the ill and the dying. Originally these were personal gifts but, by the end of the decade, they had become an essential part of the growth of AIDS activism (Harris 1994: 55-56; cf. Varga 2009: 79). The findings of the study presented in this chapter aim to highlight the important continuous and active role of toys in fighting the negative effects of a global health crisis through toy play and, in particular, the seemingly endless presence of the teddy bear in times of crisis.

Method

Play has been studied via diverse methods, such as observation in a natural environment, observation in a structured environment, interviews and questionnaires, and examinations of toy inventories, pictures and photographic records, or other evidence of children’s play (Smith 2010). In this study, object play is addressed and analyzed in the light of the empirical data collected from different sources, namely media articles, personal interviews conducted online and ‘live’ toy photography posted on Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram, following the idea of triangulation (see, for example, Stake 1995).

In order to study the phenomenon of the Teddy Challenge, the author conducted a research trilogy with phases performed in March-April 2020, June-July 2020, and the spring of 2021. First, the study sought to map out the phenomenon by analyzing articles collected online from news media in Finland, the USA and the UK. Second, online interviews with seven toy players from Finland, the UK and Singapore were carried out in order to find out about toy play patterns in general during the lockdown period of spring-summer 2020. Third, and finally, the study analyzed pandemic toy play during the second wave of the Covid-19 virus in Finland through a thematic analysis of a new set of online toy photographs relating to the replaying of the #teddychallenge and shared by regional Finnish news media in March-April 2021.

Figure 7.1 Data collection and analysis: Methods used for the three-part study

CC BY-NC 4.0

Liberated through Toys: Three Stages of Pandemic Toy Play Investigated

Unusual and uncertain times seem to influence toy design to produce novel playthings. Toys focusing on development of prosocial tendencies, such as empathy, emerged in the 2000s, but the beginning of the Covid-19 pandemic caused an upsurge in the toy market’s offering of character toys depicting figurines and dolls as action heroes serving as guardians of our well-being. For example, in response to the ongoing health crisis, Mattel launched a series called Fisher-Price Thank You Heroes, including collections of plastic play figures consisting of series of nurses, doctors, delivery drivers and emergency medical technicians, as well as a series of ‘community champions’, ‘who work hard every day to help us stay healthy, safe and stocked with everything we need’. Furthermore, in 2021 the company launched a Barbie toy portrait of the real doctor Sarah Gilbert, a developer of the Covid-19 vaccine (Reuters 2021).

Instead of new toys that draw their design inspiration from the human heroes of the ongoing pandemic, the study explained in this chapter focuses on a universally recognized and loved plaything—the teddy bear. Teddy bear plush can be found in many homes and can consequently be considered a sustainable toy which represents long-term play value for players of many ages. According to an article published in the Telegraph, more than half of Britons still have a teddy bear from childhood and the average teddy bear is twenty-seven years old (Telegraph 2010). Besides their role as domestic artefacts with decorative and affective value, teddy bears have featured in professional portraiture of children. Plush toys have been deliberately used as props in portrait photographs—the practice of photographing a child with his or her favourite teddy bear, for example, was common by 1907 (Walsh 2005).

In the contemporary world, plush characters come alive in ‘photo-play’ (toy photography), a popular play pattern associated mainly with character toys, such as dolls, action figures and soft toys, dependent on camera technologies, social sharing and most of all the creativity and imagination of the players. The largest part of contemporary photo-play illustrates character toys displayed in arrangements of various sorts. The making of toy displays requires versatile physical properties and mechanical affordances of the toys, such as articulated limbs which are either overstuffed for sturdiness or have an overtly soft stuffing to achieve a slouchy and huggable appearance. The design of teddy bears has made them poseable from the beginning. The poseability of teddy bears differentiated them from the early commercial dolls that were mostly made of wood, composition or porcelain—the teddy bear was a more ‘huggable’ toy from the beginning (Walsh 2005).

The photo-play explained in the following section has made use of the teddy bear’s affordances in terms of aesthetics and poseability. In other words, they allow creative and experiential toy photography due to their articulation and looks which, combined with current camera technologies, breathe life into the toys and invite anthropomorphization of the playthings. Photo-play is central for analyses of #teddychallenge, which took place in three consecutive phases of study, elaborated on in the next sections of the chapter.

Figure 7.2 Photo-played display of three plush toys taking part in the #teddychallenge, 2020

Photo by Katriina Heljakka, CC BY-NC 4.0

Ludounity: The #teddychallenge as Playing for the Common Good

Long before the Covid-19 pandemic, Donna Varga wrote about ‘the attempt to replace the dearth of social contact with a material object’ (Varga 2009: 81). Approximately ten years after Varga’s foundational research on teddy bear cultures was published, teddies and other plush toys appeared in window screens as a firsthand, communal reaction to the uncertainties presented by the new health crises in association with the outbreak of the Covid-19 virus. The simultaneous occurrence of teddy bear displays in many countries, and even different continents, accentuated the human need for participatory play, the essentiality of photo-play and the social sharing of the activity. The play pattern was also accompanied by a gamified goal—a challenge based on the spotting of teddies offline in windows of houses and online through the screens of mobile devices and social media that attracted players of different ages. Inviting children and adults to create, narrativize and hunt for toy displays, the #teddychallenge became a popular phenomenon widely covered by the media across the globe.

While players could take part in the challenge online by looking at the toy displays photographed and shared by others on social media, offline participation in the #teddychallenge began with setting up a display of toys in a window. In Daniel Miller’s view, a visual display is always complemented by the possibility of a story (Miller 2008) and the visually displayed stories of teddy bears are a documented part of early commercial toy history. An example of this is the fact that ‘after the 1912 Titanic sinking, Steiff produced black mourning bears; these were part of a window display at Harrods and for sale’ (Cockrill 2001; cf. Varga 2009: 76).

The first phase of the study examined the phenomenon of the teddy challenge, analyzing its motivations, messages and manifestations. As a physically and spatially emerging form of play, it was perceived as a gesture of solitary play. Moreover, there was a strong social statement lurking behind the window screens, a form of toy activism that sent out a message about the mental and creative agility and empowerment of players living in quarantine. The motivation for the teddy challenge, then, was to join forces in the name of social play. The message of the #teddychallenge was a pledge for togetherness. Finally, the manifestations were as creative as the players in terms of their skills in handicrafts, storytelling, displaying wit or willingness to place toys centre-stage with the purpose of functioning as stand-ins and spokespersons. The first phase of research revealed playing for the common good as a strategy for surviving a socially challenging moment in time. In the beginning of the pandemic, the world was at (toy) play for ‘ludounity’ (Heljakka 2020).

Intergenerationality: The #teddychallenge as an Intergenerational Play Practice

According to Bengtson, multigenerational relationships will be more important in the twenty-first century for three reasons: a) demographic changes of an ageing population, b) the importance of grandparents fulfilling family functions, and c) the strength of intergenerational solidarity over time (Bengtson 2001; cf. Cohen and Waite-Stupiansky 2012). The second phase of research on the #teddychallenge included interview material and photo-play from participants in three countries and demonstrated how resistance, resourcefulness and playful resilience appeared in toy play during the Covid-19 pandemic as an intergenerational practice with solitary and social qualities (Heljakka 2021). Pandemic toy play, employing teddy bears and other toy friends during the spring and summer of 2020, illustrated how playthings were displayed, narrated, photo-played and shared on social media to counteract experiences of loneliness and isolation by communicating positive playful messages of emotional survival. Players of different ages joined in the teddy challenge as displayers, spectators or social media activists, demonstrating how toy activism for a common cause may lead to many forms of play, including intergenerational play that enhances well-being. As a public form of toy play, the #teddychallenge sent out its message to grandparents and grandchildren, as well as to anyone else interested in being invited to participate in this form of hybrid play, and translated messages of support and solidarity in the form of physical toy displays, sometimes accompanied by written messages.

Optimism and Future-orientedness: The #teddychallenge as a Regional and Mobile Play Experience

The final phase of the study sought to investigate play during spring 2021 on a national and local level. To understand how pandemic toy play happened at a later phase of the health crisis, the author investigated regional play, encouraged through a photo-play challenge created by the local media, the daily newspaper SK, published in Western Finland.

This phase of the study represented another perspective on pandemic toy play—a replayed play pattern made familiar by the firsthand #teddychallenge—and combined it with the idea of regional toy tourism, or rather, toyrism (Heljakka & Räikkönen 2021), i.e. making one’s ‘toy friends’ mobile and capturing their adventures on camera. The news media invited locals to take their toys out for photo-play in nearby areas through an invitation to play presented online. In a matter of days, some one hundred photo-plays were generated and, after a few days more, the news media had collected 260 instances of photo-play from their readers.

The analysis of these photos showed how teddies and other plush were taken on outings in regional locations and attractions. Afterwards, some of the instances of photo-play were published in the local newspaper’s online and printed versions (Kauppi 2021).

In the photos, the plush were shown out and about, engrossed in leisurely, even sporty activities, like sunbathing, skiing, on sledges, climbing, hiking, having picnics, barbecuing, baking, gardening flowers, and visiting local sights and playgrounds. These playful images, taken in March 2021, by and large depicted activities that many human beings seemed to have done regionally before the pandemic one year earlier, in March 2020. At this point, the toys were depicted spending time outdoors close to home and seeking the calming yet energizing effect of visiting natural landscapes and local attractions during outdoor excursions, or resorting to homely and comforting activities within the domestic space, spending time with the family.

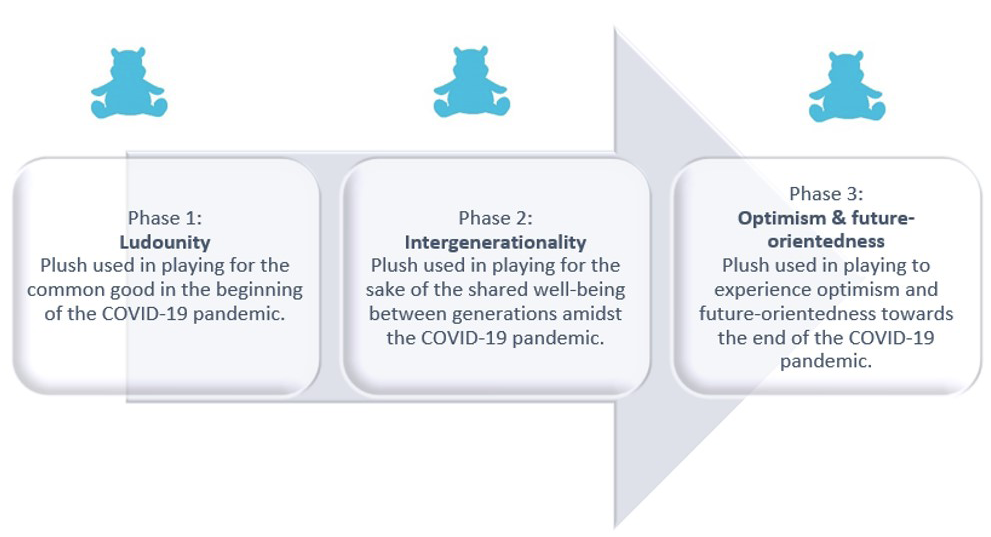

In this way, the third phase of research highlighted toy play as an activity that reflected playful resilience—optimism and orientation towards a brighter future through imaginative, creative and narrative object play mainly conducted outdoors in the public sphere and sending out a strong signal of the presence of play in challenging times. Together with the detected themes of ludounity, intergenerationality, optimism and future-orientedness, the results of the three-part study on pandemic toy play contribute to an understanding of the development of plush characters into ‘objects of resilience’—an evolutionary concept visualized in Figure 7.3, and discussed in the final part of this chapter.

Figure 7.3 Development of plush characters into ‘objects of resilience’—an evolutionary concept

Created by Katriina Heljakka, CC BY-NC 4.0

Discussion: Main Facets of the #teddychallenge

Play is neurologically a reactive itch of the amygdala, one that responds to archetypical shock, anger, fear, disgust or sadness. But play also includes a frontal-lobe counter, reaching for triumphant control and happiness and pride. (Sutton-Smith 2017: 61)

Cultures work out their feelings at play (Eberle and the Strong National Museum of Play 2009). As the quote from Sutton-Smith tells us, play is about more than combatting negativity—it is also largely about enjoyment; happiness and pride: ‘Play makes life more worth living than is the case without it. And this leads logically to the notion that optimism and flexibility are essential correlates of play’ (Sutton-Smith 2017: 224).

Imagination, inclusion and communality were the main features of the play pattern showcased by everyday players as well as enterprises and authorities represented in the media articles of the first phase of research. With the detected aspects of resistance, resourcefulness and resilience, the interviewees who participated in the second phase of research demonstrated the multifaceted nature of toy play during the pandemic. In the third phase, the analysis of the photo-play showed how toy players maintained a positive and hopeful spirit by showing their plush toys taking an active part in outdoor activities transported to participate in local toyrism.

According to the three-part study presented in this chapter, it becomes evident that toys have the power to comfort and inspire large numbers of people (Fulmer 2009). Moreover, they are fantastic creatures that are used to channel and display the products of the collective human imagination, optimistic mindset and a survivalist attitude through play in public space.

The three-part study explained in this chapter highlights mature toy players not only as solitary object players but also as social and intergenerational object players highly involved and engaged in proactive play. The #teddychallenge shows how the teddy bear, as a representative of childhood innocence, has evolved to encompass ‘social, emotional, and material capacities of transformative love’, and to become ‘a humanitarian ambassador’ (Varga 2009: 72-73).

Brian Sutton-Smith refers to Goffman when writing: ‘whatever play is, it always runs parallel to our lives, serving as a respite from ordinary events and a lesson on how life can actually be better than it is’ (Sutton-Smith 2017: 67). As toy play during the Covid-19 pandemic has proven, ‘we don’t play in order to distract ourselves from the world, but in order to partake in it’ (Bogost 2016: 233). Play is resourceful in many ways; in playing we orientate ourselves towards opportunities, seek solutions and allow ourselves to think positively about our options. Furthermore, play is social interaction as much as it is private action (Henricks 2015: 101). As shown in the chapter at hand, play is about action as much as it is about reaction and response to what the world throws in our way.

The purpose of this chapter was to explain a study with an interest to examine, describe, and increase the understanding of toy play during the Covid-19 pandemic. The three-part study showed first how the #teddychallenge evolved from a play pattern of toys being displayed and shown in windows by themselves, and second, how the teddies and other toys were liberated to move out and about with their human counterparts as the restrictions on social distancing and physical mobility slowly dissolved thanks to the introduction of vaccines around the world. Third, the study revealed how toys were taken out on excursions and depicted enjoying life in a replaying of the #teddychallenge, as encouraged by regional news media.

In the consecutive phases of the research, the author noted how communality of play emerged in the #teddychallenge, and how it illustrated a case of playing for the common good through a sense of togetherness of generations and belonging in communities. Cohen and Waite-Stupiansky claim that ‘there is little doubt that play is the unifying factor in allowing participants the opportunity to communicate and share the joys and wonders that play provides’ (2012: 69). In contemporary times, plush toys have proven their power as intergenerational playthings. In this way, play has moved from being object-centred to relationship-centred (Henricks 2015, quoting the work of Daniil Elkonin)—and more specifically about relationships between generations of adults and children strengthened through toy play.

The #teddychallenge also highlighted how toy play among the mature participants of the challenge is not about nostalgia for the past but, even more so, about interactions with toys as a response to the human condition here and now. Moreover, photo-play with plush included both toys old and new, illustrating that the toy relations of today may include all kinds of plush toys—historical and contemporary.

In association with the evolution of the teddy bear, Donna Varga has written about ‘a belief in the object’s transformational possibilities’ (2009: 79). In light of the findings of the study investigating the #teddychallenge, it is possible to think about the play pattern as a form of toy activism which addresses the capacity of plush to function as objects of resilience.

Resilience is ‘a process to harness resources in order to sustain well-being’ and the idea of progress—moving forward—is an important component of resilience (Southwick et al. 2014). In times of crisis, adults mentally resort to reinspecting objects of resilience, such as plush creatures like teddy bears—as ‘emissaries of hope’ (Varga 2009: 84). As shown in this chapter, during the Covid-19 pandemic, plush toys have worked as objects of resilience—artefacts that mobilize the human in physical, cognitive and emotional ways, strengthening our trust in survival and channelling our trust in a return to normalcy.

Conclusions: Bearers of Optimism and Hope

Toys, and soft plush creatures in particular, are both symbols of loss and sorrow but, precisely because of that, they are also bearers of optimism and hope. At the time of finalizing this study, the war between Russia and Ukraine broke out, bringing to the forefront other kinds of toy activists. The idea of toys as artefacts of hope materialized recently in the toy activist protests against Russia’s attack on Ukraine, where dolls were taken to show compassion for the victims of war.

The protective aura of plush as a gift given to soothe children (and others) during crisis (Cook 2009) became even clearer during the writing of this chapter through the droves of people fleeing the war. Finnish broadcaster YLE showcased a photography project by Abdulhamid Hosmas (YLE 2022) who portrayed Ukrainian children holding on to their character toys after they had crossed the border. A few days later, a Facebook post (In Ukraine 2022) showcased an image of a bridge on which plush toys were hung, informing passers-by that the ‘Romanian border police and citizens have turned the pedestrian bridge linking # and Romania at Sighetu Marmației into a toy bridge’. On the bridge, the toys were displayed for grabbing by children passing through on their way out of the country. Consequently, instead of leisurely toyrism as a form of toy mobility, this human tragedy has resulted in migration of donated toys, and as such represents humans’ recent wish to harness play for the common good (Heljakka 2020).

During the Covid-19 pandemic the monetary value of playthings became irrelevant and economic exchange value was replaced by emotional exchange value (Cook 2009). Toys’ capacity to move people emerges here in both physical and affective terms—the first instances of the #teddychallenge were built on the idea of the teddy bear hunt encouraging people to move about in their neighbourhood to spot teddies in gardens and windows so as—more importantly—to raise spirits despite physical and social distancing. The #teddychallenge, as a byproduct of the pandemic, reveals human beings’ neediness towards toys. Plush characters function as protective, personal and intimate trustees and comforters but also, and more poignantly, as ‘a portal of human contact’ (Fulmer 2009: 93).

Faith in the teddy bear’s presence to make everything better (Varga 2009: 81) seems again a timely wish of players all over the world. Amidst the ongoing war in Ukraine and the still lingering health crisis caused by the Covid-19 virus, toys communicate a playfulness otherwise absent in the everyday lives of those suffering from mental and physical stress. For this reason, toys can be viewed as personal and shared objects of resilience for players of many ages. As relational artefacts, they are about longevity and sustainable relationships (Heljakka 2022). Play celebrates being present and living in the moment while being supported by familiar and comforting toys.

In adult toy cultures, the object relations and interactions are still partly confined to the intimacies of domestic space. In children’s toy relationships, however, plush creatures are forever present, brought into the public space, grasped tightly in the arms of the child, channelling comfort and reassurance. But times change, and so do human relations with toys. And more importantly, societal ideas of teddy bears and other character toys are acknowledged to encompass powers of their own. The time has come to realize the importance of anthropomorphized entities functioning as mirrors, extensions and avatars (Heljakka 2023). Moreover, they have increasingly gained the capacity of independence and ability to function as toy activists. All the same, toys are not insignificant, but highly important artefacts channelling messages of hope and survival. Teddy bears, and plush creatures in general, have during the Covid-19 pandemic proved their capacity as emblems of collective hope and toy activists communicating faith in brighter times to come.

Time will tell how the materiality of these playthings will evolve but what is known now is that tangibility as an affordance is hard to replace. More importantly, what we seek from objects of resilience, besides sensory gratification, is familiarity and friendliness, poseability and huggability, a chance to care for, grow attached to, and build affectionate relationships with them—all while seeking the possibility of seeing the human behind the thingness.

This chapter has highlighted how the appetite for object play during challenging times is a sign of mental strength and playful resilience—a willingness to sustain well-being, human psychological endurance and survival. The three-part investigation and synthesis of pandemic toy play illustrates how, in times of crisis, toys may transform from intimate, transitional objects to communal objects of resilience. As proposed in the chapter, the #teddychallenge represents a form of toy activism in which toy characters act as messengers of socially significant statements. Playing and toying for the common good by combining character toys with online sharing, imaginative acts of physical object displays, socially shared photo-play and hybrid play culture, all thrive and channel a strong message of ludounity: by playing together, we will survive. Bearers of hope in shared play—the plush toys conceptualized in this chapter as objects of resilience—are an important tool for achieving ludounity.

Works Cited

Auerbach, Stevanne. 2004. Smart Play, Smart Toys: How to Raise a Child with a High Play Quotient (USA: Educational Insights)

Bengtson, Vern L. 2001. ‘Beyond the Nuclear Family: The Increasing Importance of Multigenerational Bonds’, Journal of Marriage and the Family, 63: 1–16, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2001.00001.x

Boehm, Helen. 1986. The Right Toys: A Guide to Selecting the Best Toys for Children (Toronto: Bantam)

Bogost, Ian. 2016. Play Anything: The Pleasure of Limits, the Uses of Boredom, and the Secret of Games (London: Basic Books)

Chudacoff, Howard P. 2007. Children at Play. An American History (New York: New York University Press)

Cockrill, Pauline. 2001. The Teddy Bear Encyclopedia (New York: Dorling Kindersley)

Cohen, Lynn E., and Sandra Waite-Stupiansky. 2012. ‘Play for All Ages: An Exploration of Intergenerational Play’, in Play: A Polyphony of Research, Theories and Issues, ed. by Lynn E. Cohen and Sandra Waite-Stupiansky, Play and Culture Studies, 12 (Lanham, MD: University Press of America), pp. 61–80

Cook, Daniel T. 2009. ‘Responses’, Cultural Analysis, 8: 89–91

Cross, Gary. 2008. Men to Boys. The Making of Modern Immaturity (New York: Columbia University Press)

Crozier, Ray. 1994. Manufactured Pleasures: Psychological Responses to Design (Manchester: Manchester University Press)

Csikszentmihalyi, Mihaily, and Eugene Rochberg-Halton. 1981. The Meaning of Things. Domestic Symbols and the Self (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press)

de Sarigny, Rudi. 1971. Good Design in Soft Toys (London: Mills and Boon)

Eberle, Scott G., and the Strong National Museum of Play. 2009. Classic Toys of the National Toy Hall of Fame: A Celebration of the Greatest Toys of All Time! (Philadelphia: Running Press)

In Ukraine. 2022. [Toy Bridge Facebook post], 17 March, https://www.facebook.com/1448090885498011/posts/2749767311997022/

Fleming, Dan. 1996. Powerplay: Children, Toys and Popular Culture (Manchester: Manchester University Press)

Fulmer, Jacqueline. 2009. ‘Teddy Bear Culture[s]’, Cultural Analysis, 8: 92–96

Groos, Karl, and Elizabeth Baldwin. 2010 [1901]. The Play of Man (Memphis, TN: General Books)

Harris, Daniel. 1994. ‘Making Kitsch from AIDS: A Disease with a Gift Shop of Its Own’, Harper’s Magazine, July: 55–56

Heljakka, Katriina. 2013. Principles of Adult Play(fulness) in Contemporary Toy Cultures. From Wow to Flow to Glow (Helsinki: Aalto Arts Books)

——. 2020. ‘Pandemic Toy Play against Social Distancing: Teddy Bears, Window-Screens and Playing for the Common Good in Times of Self-Isolation’, Wider Screen, 11 May, https://widerscreen.fi/numerot/ajankohtaista/pandemic-toy-play-against-social-distancing-teddy-bears-window-screens-and-playing-for-the-common-good-in-times-of-self-isolation/

——. 2021. ‘Liberated through Teddy Bears: Resistance, Resourcefulness, and Resilience in Toy Play during the COVID-19 Pandemic,’ International Journal of Play, 10: 387–404, https://doi.org/10.1080/21594937.2021.2005402

——. 2022. ‘On Longevity and Lost Toys: Sustainable Approaches to Toy Design and Contemporary Play’, in Toys and Sustainability by Subramanian Senthilkannan Muthu (Singapore: Springer Singapore), pp. 19–37

——. 2023. ’Masked Belles and Beasts: Uncovering Toys as Extensions, Avatars and Activists in Human Identity Play’, in Masks and Human Connections: Disruptive Meanings and Cultural Challenges, ed. by Luísa Magalhães and Cândido Oliveira Martins (Cham: Springer International), pp. 29-45

Heljakka, Katriina, and Juulia Räikkönen. 2021. ‘Puzzling out “Toyrism”: Conceptualizing Value Co-Creation in Toy Tourism’, Tourism Management Perspectives, 38: 100791, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2021.100791

Henricks, Thomas S. 2006. Play Reconsidered. Sociological Perspectives on Human Expression (Urbana: University of Illinois Press)

——. 2015. ‘Sociological Perspectives on Play’, in The Handbook of the Study of Play, ed. by James E. Johnson et al. (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield and the Strong Museum of Play), ii, pp. 101–20

Ivy, Marilyn. 2010. ‘The Art of Cute Little Things: Nara Yoshimoto’s Parapolitics,’ in Fanthropologies, Mechademia, 5, ed. by Frenchy Lunning (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press), pp. 3–29

Kauppi, Sari. 2021. ‘Nallegalleria’, Satakunnan Kansa, https://www.satakunnankansa.fi/satakunta/art-2000007863021.html

Kuznets, Lois. 1994. When Toys Come Alive, Narratives of Animation, Metamorphosis and Development (New Haven: Yale University Press)

Laatikainen, Satu. 2011. ‘Lelu on leikin asia [A Toy Is an Issue of Play]’, Yhteishyvä, 12: 72–74

Leclerc, Rémi. 2008. ‘Character Toys: Toying with Identity, Playing with Emotion’, unpublished presentation at the Design and Emotion Conference, Hong Kong Polytechnic University, 6-9 October

Marks-Tarlow, Terry. 2010. ‘The Fractal Self at Play’, American Journal of Play, 3: 31–62

Mayerowitz, Scott. 2010. ‘Bedtime Story: 1-in-4 Grown Men Travel with a Stuffed Animal’, ABC News, http://abcnews.go.com/Travel/grown-men-travel-stuffed-animals-teddybears-dogs/story?id=11463664

Miller, Daniel. 1987. Material Culture and Mass Consumption (Padstow: Basic Blackwell)

Newson, John, and Elizabeth Newson. 1979. Toys and Playthings (New York: Pantheon Books)

Ngai, Sianne. 2005. ‘The Cuteness of the AvantGarde’, Critical Inquiry, 31: 811–47

Norman, Donald. 2004. Emotional Design: Why We Love (or Hate) Everyday Things (New York: Basic Books)

Paavilainen, Janne, and Katriina Heljakka. 2018. ‘Analysis Workshop II: Hybrid Money Games and Toys’, in Hybrid Social Play Final Report, ed. by Janne Paavilainen and others, Trim Research Reports, 26, pp. 16–18, http://urn.fi/URN:ISBN:978-952-03-0751-6

Pearce, Susan M. 1994. ‘Thinking about Things’, in Interpreting Objects and Collections, ed. by Susan M. Pearce (London: Routledge), pp. 125–32

Reinelt, Sabine. 1988. Käthe Kruse: Leben und Werk (Weingarten: Kunstverlag Weingarten)

Reuters. 2021. ‘Barbie Debuts Doll in Likeness of British COVID-19 Vaccine Developer’, 4 August, https://www.reuters.com/world/uk/barbie-debuts-doll-likeness-british-Covid-19-vaccine-developer-2021-08-03/

Rossie, Jean-Pierre. 2005. Toys, Play, Culture and Society: Anthropological Approach with Reference to North Africa and the Sahara (Stockholm: SITREC)

Ruckenstein, Minna. 2011. ‘Toying with the World. Children, Virtual Pets and the Value of Mobility’, Childhood, 17: 1–14, https://doi.org/10.1177/090756820935281

Shillito, Adam. 2011. ‘Toy Design’, unpublished presentation at the ‘From Rags to Apps’ conference, Shenkar College Tel Aviv, author notes

Smith, Peter K. 2010. Children and Play (Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell), https://doi.org/10.1002/9781444311006

Southwick, Steven M., et al. 2014. ‘Resilience Definitions, Theory, and Challenges: Interdisciplinary Perspectives’, European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 5: https://doi.org/10.3402/ejpt.v5.25338

Stake, Robert E. 1995. Qualitative Research: Studying How Things Work. (New York: Guilford Press)

Strong Museum. n.d. ‘The National Toy Hall of Fame: Teddy Bear’, https://www.museumofplay.org/toys/teddy-bear/

Sturken, Marita. 2007. Tourists of History: Memory, Kitsch, and Consumerism from Oklahoma City to Ground Zero (Durham, NC: Duke University Press)

Sutton-Smith, Brian. 1986. Toys as Culture (New York: Gardner Press)

——. 2017. Play for Life: Play Theory and Play as Emotional Survival, comp. and ed. by Charles Lamar Phillips and others (Rochester, NY: The Strong)

Telegraph, The. 2010. ‘Third of Adults “still take teddy bear to bed”’, 16 August, https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/newstopics/howaboutthat/7947502/Third-of-adults-still-take-teddy-bear-to-bed.html

Varga, Donna. 2009. ‘Gifting the Bear and a Nostalgic Desire for Childhood Innocence’, Cultural Analysis, 8: 71–96

Volonté, Paolo G. 2010. ‘Communicative Objects,’ in Design Semiotics in Use: Semiotics in the Study of Meaning Formation, Signification and Communication, ed. by S. Vihma, School of Art and Design Publication series, A 100 (Helsinki: Aalto University), pp. 112–128

Walsh, Tim. 2005. Timeless Toys: Classic Toys and the Playmakers Who Created Them (Kansas City: Andrews McMeel)

YLE. 2022. ‘My Teddy is My Refuge’, https://yle.fi/uutiset/3-12344876

1 This research was conducted in affiliation with the University of Turku’s Pori Laboratory of Play, Finland.