8. ‘This Is the Ambulance, This Truck’:Covid as Frame, Theme and Provocation in Philadelphia, USA

© 2023, Anna Beresin, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0326.08

When the school playgrounds reopened after quarantine, you could find most parents, grandparents and babysitters picking up their children after school, or observing their children’s lingering play, gathering at the edges, moving slowly from periphery to centre. Like their movements, this essay begins with a wide-angle lens, describing play and conversations about play with parents and guardians in three public school communities in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, during the winter and spring of 2020-2021. In Philadelphia, America’s poorest large city, one school community studied here is mostly minority and middle-class in a racially integrated neighbourhood with access to parks and trees, one a mostly white, upper middle-class school community in the centre of the city, and one an almost exclusively minority, working-class school in an under-resourced, minority community. The first two have elaborate new playgrounds augmented by extensive parent-sourced fundraising. The third has no playground outside at all but a privately funded rooftop playground is in the cards as the neighbourhood struggles with gentrification. It is not unusual in this city for playground access to be so unequal, and this can be considered a social justice issue reflecting racist housing development (Beresin in press; Feldman 2019).

With ethical approval provided by the University of the Sciences, fifty adults participated in this study as well as their available children if both parties approved. In this chapter, we will see intersectional power dynamics and intertextual expressivity while the families described access to toys, games and common play spaces during the different phases of the pandemic. Although the challenges faced by each community were different, the themes of play were universal. This essay highlights the pandemic’s influence on healthy children’s social lives within their playground communities, and the pandemic’s emergence as a frame and theme, and then narrows in on children’s micro-world-building.

At the middle-class school, I was regularly greeted by two mothers who sat as sentries on the steps leading to the school’s playground. Children spiralled toward and away from the mothers, checking in about snack permissions, one small girl always carrying a large stuffed animal of indeterminate species. The mom noted that the girl carries her ‘stuffy’ with her now, wherever she goes. The mothers served as this yard’s gatekeepers, perched on the edge of the schoolyard play world while other adults leaned on the playground fence containing the newly augmented series of rope climbers, swirling slides, and variously levelled steps on a padded area. There were basketball hoops complete with nets, smaller-sized plastic ball funnels, and a wide nearby area with a painted oval for running and biking on concrete.

Twenty minutes away at the upper middle-class schoolyard, the greeters were a team of mothers and nannies sitting multiple days a week on the low wall that served as a fence for their schoolyard. Mostly women with younger children in strollers, these were the more fashionable counterparts to the first playground, guarding their charges and offering snacks while the children lingered after school to play. Their playground had also been revitalized a few years earlier with major fundraising from both the parents’ association and local companies to the tune of one hundred thousand dollars. This playground sports a metal climber, several slides and, most unusual for school playgrounds, several rubberized mounds simulating small rolling hills often used as a base for Tag and for momentum-filled running or biking.

Another twenty minutes away, a third school has no playground at all. The concrete area that was designated originally for play is mostly used as a parking area for the teachers’ cars. I was greeted regularly here by a grandmother picking up her granddaughter and great-niece, both of whom live with her. ‘Every week a new Barbie’ at the local Target provided them with a much-needed opportunity for getting outside the house during the pandemic, as outdoor play spaces were limited.

The study began as a series of videocall interviews via Zoom utilizing a snowball sample that started with my next-door neighbour’s family during quarantine in the winter of 2020. Quarantines were established by each school district within each state in conjunction with local governmental decisions. As the quarantine shifted, I began weekly observational studies with ethnographic interviews in these three different school communities, each a school where I have done extensive fieldwork or had known contacts. Previous research by this author was carried out in two of the school communities, one with daily observation over several months’ time, the other with weekly observation over a span of five years (Beresin 2014; Beresin 2015). The third community school is within a few blocks from my home where I have lived for twenty years. All are public kindergarten through eighth grade schools in Philadelphia with an approximate enrolment of five hundred students serving children ages five through fourteen. Parents and guardians were recruited through neighbourhood posters, parent teacher association Facebook pages, word of mouth, and on-site during conversations in the schoolyards. Children were not interviewed on the playground, as this researcher did not want to interrupt their important play time although, if approached and the parent or guardian was present, their words were recorded by hand with pen and paper. The children were invited to contribute drawings or photos of their currently favourite toys and activities, as long as there were no images of the children’s faces.

All quotes that follow are verbatim, and often the adults quote their own children. Many have had a front-row seat to their children’s worlds during the pandemic, given that parents were often themselves working from home, were unemployed, or were supervising their children’s online schooling. At the time of the interviews, the families were healthy, although several had lost relatives to the disease. The methods here are qualitative and improvised and the material carefully transcribed, given the rush to document children’s lives at the time of the novel coronavirus (Erickson 1990; Tannen 2007). As I write this, the Delta variant is receding and the Omicron variant is surging, directly affecting the young.

This author vowed to protect the families’ privacy as this time was particularly vulnerable, bordering on the traumatic, according to the early Zoom interviews in this study. Ordinarily in ethnographic research, there would be more description of each person who speaks in the excerpts below. It can be said that parents’ vocations ranged from the recently unemployed, some by choice, to epidemiologists, plumbers, teachers, lawyers and artists, a full range of educational backgrounds and social classes. The interviews included white European American, Latina/Latino, Asian American and African American adults. They varied in age from parents in their early twenties to late forties, all with children in one of the three kindergarten-through-eighth-grade schools in the study. The parents as a cohort voiced their appreciation and the sense that we were documenting this time together as a collage, and that it was a task worth doing.

Playgrounds

Parents and caregivers in the middle-class school playground voiced their appreciation of the newly renovated space utilized for both recess and for after-school play. This included emphatic comments relating to this particular playground, shown below in bold:

Everybody loves this playground. It’s the best place to hang with other parents, a safe watering hole.

We come here literally every day. Never stopped. Coming here has been a lifesaver. We came even when it was cold, just not in the rain. My son comes here after school. Even though he hasn’t been in face-to-face classes, he hasn’t missed out on the socialization piece. He met every school kid at the playground.

It’s much better now. We’ve been at this playground as much as possible since Covid started. It was closed initially, maybe in April or May it opened. We’re here at least three times a week. Sometimes five. She has a whole crew she meets here.

The playground is so wonderful. It is such a wonderful place to safely gather with other parents after school or on the weekends. It’s just a great place for our community to be.

Now the only place to move is the playground.

My daughter would call out to other children in the playground, ‘Are you in Ms. J’s class? Are you in Ms. J’s class?’ Without the playground, I don’t know how she’d meet her classmates in person. It really helped a lot to meet other kids, even one hour a week. I feel for families who don’t have any access to outdoor spaces. I have so much privilege. At her old school in Philly, they had a policy of having to leave the playground after fifteen minutes of play and then they close the gates. Not here! No one kicks us out. We’re sometimes here until 6:30, and we can stay.

We go to the playground a lot. We meet other families here. . . The playground, we go usually once a week. It’s always buzzing. I avoided it early in the pandemic. We didn’t know enough about the virus, how it was transmitted, if they could get it on surfaces. So many unknowns. As months go by, we are more comfortable. We still wear masks and bring hand sanitizer. For me, it’s been nice to see people once a week. I used to enjoy walking the kids to school. I missed that, seeing people, chatting. We would linger with no agenda. I really did miss that.

In the upper middle-class neighbourhood, the parents had different challenges and other advantages in terms of resources. Some children went to high-end afterschool gyms and were there on off-days when school was completely online. Some went to second homes and spent online school time in vacation-ready isolation. After school, families were supposed to leave the playground, as it was officially closed right after dismissal. Some stayed anyway. There was frustration over the idea of having to leave the playground oasis, along with a newfound appreciation for its social function for parents as well as children.

Today we were told to leave at 2:50, but we didn’t! They’re in six-feet-away blocks in school and only have one recess in the afternoon. At 2:50 we’re supposed to leave, as of today. (Don’t tell.) Tomorrow we may go to the other playground, next to the river. I can’t imagine walking back home and coming here again at 4:30 when it opens again.

The school says so because more students are back in school. Children cannot linger in the playground. After 4:30, I can officially come back. I can’t walk home and walk back. They’re trying to limit Covid exposure. I don’t think it’s coming from the school, this directive, but from the district. At another local Philly public school nearby, they can’t play on the playground until the last kid has been picked up. The principal, she shoos them off. ‘Can’t play here!’ They stagger them after school and in the morning.

Don’t tell, we’re still here. It’s technically not the school’s playground. It’s a public park. That’s why there’s no fence. Parents here asked for a gate but they can’t do it.

We have no pod. My wife has a group of friends. That was it, united by a ‘pinky promise’ to be safe with each other. We two dads ran into each other today (at the playground), a kind of ‘random fathers club’. Just tell me where to go and I go.

We are fortunate, we have neighbours with kids, all close during this whole thing. It’s a close school group here at the playground.

They typically go to the other public playground, or stay here, on the in-person days. The younger one does her virtual days at a gym daycare. The older one does her virtual schooling at home and then goes to the same gym a few days a week, and also takes a foreign language. All of the children they’ve played with are from the school. All from school.

This is where they want to play, at this playground.

There was nothing to play with in the working-class neighbourhood schoolyard. While waiting there, children played with objects or people they brought from home and soon quickly dispersed.

Pods

Pods, self-selected small groups or bubbles for socializing, were more common in the middle-class community as families sought ways to co-parent while working, allowing their children to have much-needed social time. All three communities spoke of proximity leading to social groupings, whether they were families on the same street, in the same housing development, the same preschool, or through the importation of relatives to watch the children. For some families, it required new efforts at organizing social time:

From what I’ve observed, it’s about half of the kids who are in pods.

The Fairy Podmothers is definitely what we’ve become, so I spent the better part of this morning arranging with them. ‘Who wants to meet for sledding across the street?’ Especially the one Pod-Mom who does still work from home—she has less of an opportunity to hang out with us in the afternoon. She has to work.

I think it’s been a really great experience for my daughter to have this pod, this safe haven experience of kids and parents who live right in our neighbourhood over a block, for her to feel secure in her community in this insecure chaotic time has helped her mentally and emotionally. I think that will carry on, even after the pandemic is under control. So, I’m feeling hopeful that we will continue some kind of cooperative parenting approach, even after we all go back to school. It’s been great that way.

In the working-class community, sticking with the immediate family was more common:

It was just us. Me and him.

They don’t socialize online. No. They play with each other, they do. I’ve been thankful they have each other.

At home, he plays with toys. (‘Toys?’) LEGOs. Yes, LEGOs. Mostly games on my phone. Roblox and stuff. (The child chimes in, ‘I like to watch YouTube and play with my sister’, as he looks at her adoringly) Who do they play with? Each other. Only each other.

Parents in all three communities voiced their concerns about the pandemic’s impact on the children’s socio-emotional lives:

For the little one, so much of her play, her entire play, her entire memory is of the pandemic.

My son and the girl neighbour had a conversation, ‘If my mom dies, mom gets sick with Covid and dies’, he said he ‘would go live with them’. He said, ‘I don’t remember what my friends look like without their masks’.

The first night of the pandemic she was up for five hours, the first night we were told there would be no school. . .the stress was incredible. And you couldn’t really see it, I didn’t see any change in behaviour but sleep just vanished. It was incredible. . . She called it the Dumb Virus early on, and so we call it that. . . the pandemic doesn’t show up in their play. I don’t ever hear them ever imagine things that are related to it.

Our son says if he doesn’t want to do something, he’ll say, ‘We can’t because of Covid’. Like, ‘We can’t go to the amusement park because of Covid’. But also, ‘I can’t go for a walk because of Covid’, or ‘I can’t go to get groceries with you because of Covid’. (She rolls her eyes) It’s listed as a stock excuse, ‘I am tired, it could be Covid’.

One day she was sitting and literally fell off her chair. I don’t know what exactly, she just kind of fell over. Paying attention is harder. . . She just is missing her friends more and more.

And yet,

Covid- it’s not a negative for some children. Some get to spend more time with their parents. Before I was working four jobs. And I still came here to pick up my daughter after school. I was beat. Now, I work from home online. I was able to sit there and teach her from home. Covid was my break! I felt like I was part of her childhood. It gave me a chance to spend more time. I don’t want to go back to face-to-face work. I need to be there seven hours a day to help her.

Covid as a Frame for Online Play

Covid emerged as a rationale for online play but rarely as a motif in online play. Many parents in all three communities were deeply ambivalent about screen time, a phenomenon Jay Caspian Kang calls ‘the great child-rearing panic of the 21st century’ (Kang 2022: 24):

Oh God. Any rules about screen time went out the window during Covid.

Online play equals YouTube. Goofy challenges. How to make slime. Spicy food challenges. She’d like to do it too, but she knows I’m not a fan.

What does he play? ‘Basketball!’ he says excitedly. (‘Outside?’) His mom lowers her voice. ‘Mostly on his phone, or on a system, a computer too’.

If it’s not outside, then they gravitate to the screens—Wii, tablet, phone, tv. It’s a battle to divert them from screens.

Toys? (They all roll their eyes) We try to get them off the tablet, off of YouTube. She shifts off school work and continues for an extra hour, sneakily. I ask if she’s finished and she admits, ‘Oh I’ve been finished for an hour’. Her neighbour nods. When they’re home, they revert to the screen so we try and keep them outside.

We regularly FaceTimed grandparents. The older one did some FaceTime with a few friends. Some out of state, some local. The younger one has one friend she FaceTimes with, and some aunts, or does Kid Messenger. Or is it Messenger Kids? They have games you can play with other people. We try to vary it. Sadly, she could be on the computer 24/7.

She’s hooked on it too. She’s hooked on watching, with Minecraft, when they actually have it (the toy) right there!

Sometimes the YouTubers simulate pranks. I hate that, so no more YouTube. But you get so tired, and you have to cook dinner and work.

They live in the same world, but they are in different worlds. When asked, ‘Don’t you want to talk to your cousin and grandparents?’ ‘NO!’ And grandparents get so mad. Yes, grandparents get so mad on FaceTime. But if you ask if they want to play with someone on Minecraft, they jump online.

It is difficult as he has ADHD. They all got distracted with YouTube and online games. I would not have introduced the computer at his age. He had to be on for school. He asks for Minecraft. He tried a few Minecraft knock-off apps. I told him I didn’t think he was ready.

Winter was hard. They did lots of drawing tutorials on YouTube. Video chats with grandparents. (The child comes up to me cautiously and the parents explain I am studying kids play.) What do you play? ‘I like to watch tv!’ and runs off. (Parent rolls eyes) She will often say, ‘Pretend we’re a family’.

They still watch way too much YouTube. Oh God. Videos of other families. They just follow rich families, that’s how they make their money. Like vlogs. I don’t know what it is about them, especially for her. I keep telling her, that way of living is not typical. He likes the educational stuff. She is into Spy Ninjas. Looks at all the reality tv. No cartoons, or shows. Just reality tv.

Online? We are pretty strict, much to my son’s chagrin. We don’t let them play much online. They watch PBS Kids. There are some computer games the computer teacher set up on their website. They can pick up anything from that page: Brain Pop, ABCya, Pebble Go, Room Recess.

His favorite thing is to play piano on a keyboard and learn from YouTube. After school, I have him get off the screen.

It used to be Pokémon. Now it’s Bakugan.

And LOL Dolls. Girls are all into them.

So much time on the screen. He’s hooked. Nintendo Switch. YouTube.

Some parents were adamant that online games eliminated imaginative play:

Imaginary play stopped when they were online for school. They wanted to do online games only. But it came back when we took them out of school. The older one would have been fine staying hybrid. The six-year-old, it was significant for the kindergartener when we made the change. They would say, ‘When can we watch?’ It was addictive. They were losing their youthful sense of wonder and creativity, so we had to set limits. And then we took them out of school completely. So much of kids’ play is on the computer. It’s that addictive, the nature of it.

Ah, it’s unfortunate. We were a family that never had a tv. If we watched a movie, it was once a year. Now they are addicted to YouTube. My twins. It’s been awful. I went to online forums, ironic huh, and spoke to the school teachers. I blocked YouTube and only did kid YouTube, and the kids figured out how to unblock it. So, I teach them to be good consumers, to make media and not just consume it. I took a class at the Penn Graduate School of Education. Piaget and Vygotsky would be rolling in their graves. Whenever they went on screens, they stopped playing and had a meltdown when the screens were stopped. But when they went back to their toys, they played instantly.

Some parents were more positive or clearly neutral about technology:

The older one does a lot of Prodigy, a math game. When you get things right you can get stuff at a virtual shop, fix up an avatar and dress it. The first graders, two girls and one boy—their play was lovely. They did superheroes often. Pokémon was a big theme.

The first grader takes lots of selfies and likes editing them, changing the backgrounds. YouTube Kids is like a rabbit hole. They both like it, to make crafts for dolls. The other day I had a splinter. She asked, ‘Want me to get it out? Put glue on your hand, let it dry and peel off the glue. Out will come the splinter’. How did she KNOW that? YouTube!

Online, they play Roblox and an RPG [role-playing game]. It’s age-appropriate, a restaurant, mall type thing, race car simulations, or Roblox, an off-brand Minecraft.

Inside, it’s the sofa. That they jump on. They got Nintendo Switch. It’s a treat on weekends. 30 minutes and we close it. She’s okay with it. She’s a rule follower.

He socializes online with his class. He’s big into Zelda and Luigi’s Mansion. Recently he’s into LEGOs.

They draw and do drawing tutorials online. They can do computer, if they are doing science research. They do Xbox. (‘Xbox!’ the children echo.) Uno. (‘Uno!’) And Switch. Lots of Uno. And Uno Attack- you hit the button to get specific cards.

We do Draw with Moe for online activity. In the beginning, for a while, until depression set in. Now it’s normal.

An older sister offers that after her sister watches a TV show, she replays and reenacts the whole show.

She’s in Girl Scouts and that’s all virtual. They socialize online in Scouts. She does soccer too. I do everything to try to keep her occupied. Scouts did a scavenger hunt online. Cooking online, too.

He plays in the Minecraft world, plays with Brazilian cousins in Canada. He waits for her to wake up.

The online world was clearly a source of tension yet also connection, even as adults also admitted that they, too, turned to television and computers for both work and recreation during the pandemic. According to the anthropologists of childhood, children’s play cultures have always reflected adult work, miniature exaggerated versions of the adult world, whether it be children playing farmer in the fields of farming towns or pretending to be fishing in fishing villages (Konner 2010; Lancy 2022; Sutton-Smith 1986). It is no surprise that children turned to online building activities like Monument Valley 11 or Minecraft or Roblox as their parents connected to Excel sheets, Word docs, and Zoom meetings. For some children and adults this online focus of school and play was stressful: ‘Developmentally, they can’t sit in front of a screen for seven hours’. ‘My daughter said she wants “to kill the internet”’. Yet for many, online play offered a kind of transitional mode, a space between the world of objects and individual thoughts and the online social world of work and school.

Covid as Theme

Parents in each community have agreed that Covid as a theme has emerged in their children’s play, although some were quick to deny it, as if its emergence was somehow a sign of fragility or weakness. Our conversations on Zoom and in all three school locations yielded phrases like, ‘No, Covid has not come up in my children’s play’. But when I offered that many children have been playing doctor or nurse, or have put masks on stuffed animals, the response has consistently been, ‘Oh, they play doctor forever’:

She does a lot of, you know, her dolls get Covid tests, her dolls get fevers, her dolls go to protests about the teachers not being safe. Her dolls are living her life. And I’m trying to think, well the older daughter was just drawing and painting viruses. She drew viruses, she drew antibodies. She drew vaccines. It definitely comes up.

A mom sighs, the dolls and animals wear masks and are ALWAYS getting a vaccine.

There’s a lot of going to the doctor, going to the hospital. That kind of stuff has definitely come up for them. I think it subsided a little bit.

They would make like ten masks for their dolls and stuffed animals in virtual play.

At the LEGO store, the kids noticed that the LEGOs had masks. In Switch online, you can choose to have your avatar with a mask, but she does not choose it.

When they play school, it’s ‘Masks on! Now we’re going outside!’

When I wasn’t feeling great after being vaccinated, the kids gave me a check-up and brought me a snack tray.

A trio of boys are running a candy, soda, and chip sale at the base of the school playground steps, hawking their wares. One handmade sign says, ‘No mask no seRvice’ in large, mixed lettering.

Half of the stories about Covid play involved exaggeration:

The young one has a doctor’s kit. He’s been giving us shots. He gives us shots, me and my husband, in our eyeballs and all kinds of places.

Covid comes up all the time. I am a nursing student in a masters’ program. When I’m not nannying, I work in a Covid testing site. All told, sixty to seventy hours a week. She’ll ask me questions. She’s seen me in scrubs from head to toe and an N95 mask. She put one of her toys in a box and it ‘couldn’t play with any of the other toys because of Covid’. She puts hair scrunchies on her stuffed animals as masks. She knows what a pulse oximeter is. She’s a very curious kid. . .

I volunteer for Philadelphia Fights [Covid] and volunteer to help people get the vaccine. She asked if we give out stickers. When I said, ‘No,’ she said, ‘What’s the point of getting a vaccine if you don’t get a sticker?’ So, she made stickers, printed them out. It says, ‘I got my VACSIN’. (She shows me the image, vaccine proudly misspelled alongside a diagonal stock image of a needle and a small mask that says, ‘Wear a mask’) The child is annoyed that she’s too young to get a vaccine, though. She knows what a nasal pharyngeal wall is. It did make me sad when she put her one toy in a box, in quarantine, and said, ‘You’re not allowed to play with the other toys’. That toy couldn’t hug the other toys. That’s been affecting her. She tells me that when they play Tag at school, they can’t touch each other.

They pretended a lot of their toys had to be six feet away. Or ten feet away. Then they would ask, ‘When could we be outside?’

The three-year-old likes playing with his mask like a slingshot.

Just today, we ran into a preschool friend of hers here at the playground, ‘Jane’. We said, ‘Hi Jane’. ‘Oh no. Jane has Covid. I’m Rebecca’, the other girl insisted. At first, we thought, ‘Oh no, Jane has Covid,’ then we realized it was an imaginary friend. A new identity. Jane [aged 5] is now Rebecca because ‘Jane has Covid’.

Sometimes exaggerated play emerged indirectly as a by-product of Covid, like these tales of escape. Here Covid frames other kinds of play:

I actually, this isn’t like me, but recently I ordered a ton of toilet paper, ‘cause there was a thing where you couldn’t get it. I do not want to worry about that this year, so I had this GIANT box and I brought it in, and asked them what they wanted to do with it, and the oldest saw an airplane. They build—they do this really well. The older said, ‘I see an airplane’ and the four-year-old said, ‘Oh yeah, let’s put windows over here’, and then they created this giant airplane that they were riding in for days.

The four-year-old, she’s really into bags. (She laughs) She’ll convert many things into a carrying vessel. It might be an actual bag or backpack and she’ll stuff it with all kinds of stuff. I think she’s going places. She might be at school. She might be going on vacation. She has the thing that she’s doing. Or she’ll stuff all her baby stuff into it. It’s amazing what can be created into a vessel to carry something somewhere. And then all the stuff moves to a different part of the house. That reminds me, she asked me for a suitcase for Christmas.

When my seven-year-old went back to school recently, the four-year-old pretended she went back to school, too. She got dressed, took a ‘first day of school picture’, and packed a backpack including her ‘computer’.

He’s always loved his stuffed animals, but he’s gotten a lot more attached to them, since all of this. And it’s been like a different one every week. . . He has this enormous elephant. He is dragging it around the house. Every time they have show-and-tell, which is not often because it takes up so much time, and listening in to each kid do show-and-tell is the cutest thing you’ve ever heard, so having him haul this elephant and shoving it in front of the laptop is very funny.

One parent said her child’s ‘dolls were living her life’. It seems that the children are also using the toys to play with their lives through distorted exaggerations that may allow the fear to be managed. Vaccines are in eyeballs. Suitcases are packed and moved to different parts of the house. Masks are toyed with like slingshots and created out of hairbands. The most extreme version was the child who claimed a new imaginary identity for herself, as her real ‘self’ had Covid and apparently disappeared. Jean Piaget called play ‘the primacy of assimilation over accommodation’, meaning children will modify the information around them to fit within their own concepts, or here, to fit their own life patterns. Yet, as Brian Sutton-Smith argued in his letter to Piaget, what emerges is not a mere copying of the real world (Piaget 1962; Sutton-Smith 1971). There is an attempt at stretching reality, not just assimilating it. There also seems to be a connection between the dreamy, stretchy surrealism of play and its connection to healing, according to psychologists from Melanie Klein to Erik Erikson to Virginia Axline (Klein 1975 [1932]; Erikson 1975; Axline 1947). The child who appeared the most stressed and did not sleep for days when the pandemic erupted was the child whose play remained untouched and unstretched by the subject of Covid.

Many families spoke of stuffed animals or ‘stuffies’ as particularly important to the child at this time. Sometimes it was a specific toy, like the enormous stuffed elephant, and sometimes the favorite toy shifted from week to week, often within a specific line of toys. As one parent wrote about her child’s stuffed animals, ‘They go to school with her in the morning, hang out with her around the house and go to bed with her at night’. The object is not just a loved transitional object, it is imbued with special powers (Winnicott 1977). A theatrical object of relational connection made visible, we see them in cartoons like Peanuts with Linus’ blanket and Calvin and Hobbes with Calvin’s stuffed tiger. Yet, Covid has brought the discussion of comfort objects into view as mini social worlds that are controlled by the child, some of which are slept with like traditional transitional objects, some of which are collected and carried everywhere, and some of which are in beloved worlds online, serving as their own kind of electronic social bridge during isolation, all providing rituals of comfort at this time.

World-building as a Folk Practice

As parents arranged and rearranged their families’ lives during the pandemic, children arranged and rearranged their toys as a folk practice in all its inequality. Their domestic world-building is not just a mirror of their real pandemic world. James Christie noted that at play ‘new meanings are substituted, and actions are performed differently than when they occur in non-play settings’ (Christie 1994: 205). Simple re-creation of domestic schemas in animal and human play worlds is itself often associated with extreme stress, as compared to playful schematic hybridity or inversion (Axline 1964; Burghardt 2005; Stallybrass and White 1986). In the final examples below, the children are playing out their worlds dialogically without any obvious dialogue, offering their domestic scenes as artistic offerings (Bakhtin 1981; Flanagan 2009; Pasierbska 2008; Opie, Opie and Alderson 1989; Sutton-Smith 1986, Sutton-Smith 2017), as iconic Covid puzzles.

One parent described a child’s repetitive play of being ill and of being rescued, acted out through Anna and Elsa dolls from Frozen (Figure 8.1). This is excerpted from a longer Zoom interview.

Figure 8.1 ‘Playroom’ (22 February 2021), Elliott, aged five

Screenshot © Anna Beresin, 2023, and used with permission

In the example above, the movie-inspired characters play out the child’s concerns like a song on repeat but the child mixes hospital narratives with amusement park toys as spoken by the movie characters. For another child, world-building was reduced to architectural designs of impossible buildings, like the art of M. C. Escher in Figure 8.2.

For others, the pandemic was a time to turn inward and was partially lived in a screen-filled home, shown here as Figure 8.3. This chalk drawing of a satellite dish was found rubbed onto the schoolyard that had no playground.

Figure 8.2 ‘Monument Valley, an Ustwo Puzzle Game’ (23 February 2021), played by Mona, aged nine

Photo © Mona’s parent, 2023, all rights reserved

Figure 8.3 ‘House with Satellite Dish’ (28 April 2021), chalked by a child on the schoolyard with no playground

Photo by Anna Beresin, CC BY-NC 4.0

One could say that the satellite drawing and the impossible house image do not have specific connections to the pandemic, yet the latter was chosen by a child as her favourite pandemic activity. The satellite dish was one of only three images chalked during the entire research period in the one community, alongside a faint image of a frowning girl and a lightly drawn flying superhero. Recent publications in the folklore of online play suggest that the division of the online world and the ‘real’ world is more permeable than previously believed (de Souza e Silva and Glover-Rijkse 2020; Willett et al. 2013). Perhaps online play—from the more passive forms of television and YouTube to the more active open worlds of computer games, video games and movie-related toy play—all can be considered a kind of world-building doll play, a spectrum ripe for research.

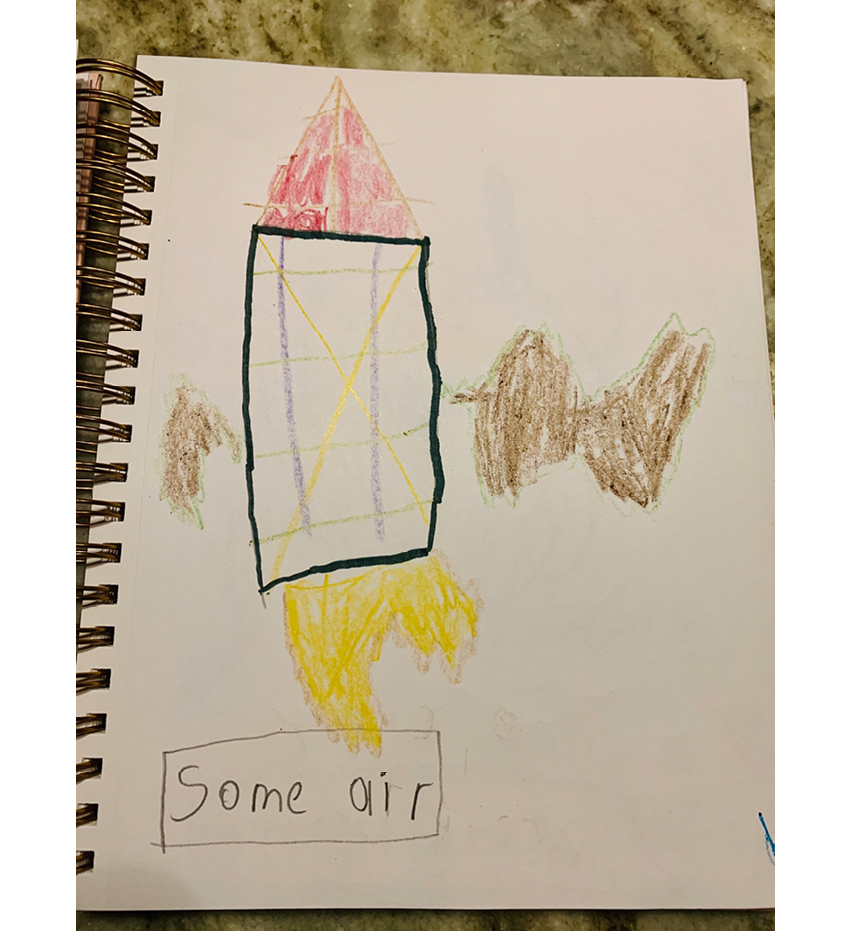

Brian Sutton-Smith writes, ‘Children’s play fantasies are not meant only to replicate the world, nor to be only its therapy; they are meant to fabricate another world that lives alongside the first one and carries on its own kind of life, a life often much more emotionally vivid than mundane reality’ (1997: 158). For some children, this has been a time to go further inside the self, shown here in this drawing of a child’s imagined rocket in Figure 8.4.

Figure 8.4 ‘Some Air’, Conor (9 April 2021), aged seven

Photo © Conor’s parent, 2023, all rights reserved

The father said it was drawn in the child’s thinking place during quarantine, the glass-enclosed porch at the front of their house, as the child would go there to watch people walk by as a liminal form of social life. The rocket was up in ‘some air’, and when he needed ‘some air’ he would go to his porch. The seven-year-old took particular pride in naming his drawings himself. Note the intense marking of the box with its windows at the centre, the child simultaneously escaping the house and the pandemic world.

And some children were busy in their pods, building new frames in more than one home, transitioning from this reality to a different one.

They’ve been doing a lot of building villages. Two kids will go and build like a school, and another will build a library and add on a fire station or a police station. It’s almost like they’re trying to find out, since we’re not out in the real world, ‘what does a village look like’ kind of thing. There’s been a lot of taking care of each other and friends taking care of each other in different ways; that’s come up quite a bit. And they’re really into using little figurines that they’ll include when they build a LEGO house. . . They are creating their own imaginary society in a way. It’s kind of interesting. All of the parents have talked about that, all have observed them in our homes. They will come to read to the others and give a prize. They are their own little society. I’ve never seen this kind of play play out before.

Perhaps this is play’s greatest gift to our collective survival, exaggeration in communities both real and imagined, moving from this ambulance to some safe new place with air.

Works Cited

Axline, Virginia. 1947. Play Therapy: The Inner Dynamics of Childhood (Boston: Houghton Mifflin)

——. 1964. Dibs in Search of Self (New York: Ballantine)

Bakhtin, Mikhail. 1981. The Dialogic Imagination (Austin: Texas University Press)

Beresin, Anna. 2014. The Art of Play: Recess and the Practice of Invention (Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press)

——. 2015. ‘Pen Tapping: Forbidden Folklore’, Journal of Folklore and Education, 2: 19-21, https://jfepublications.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/webJFE2015vol2final.pdf

——. In press. ‘Unequal Resources: Space, Time, and Loose Parts and What to Do with an Uneven Playing Field’, in Play and Social Justice, ed. by Olga Jarrett and Vera Stenhouse (Berne: Peter Lang)

Burghardt, Gordon. 2005. The Genesis of Animal Play: Testing the Limits (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press)

Christie, James M. 1994. ‘Academic Play’, in Play and Intervention, ed. by Joop Hellendoorn, Rimmert van der Kooij, and Brian Sutton-Smith (Albany: State University of New York Press), pp. 203-13

Erickson, Frederick. 1990. ‘Qualitative Methods’, in Quantitative Methods/Qualitative Methods, ed. by R. L. Linn and F. Erickson (New York: Macmillan), pp. 77-187

Erikson, Erik. 1975. Studies of Play (New York: Arno)

Feldman, Nina. 2019. ‘Why Your Neighborhood School Probably Doesn’t Have a Playground’, WHYY Radio (6 February)

Flanagan, Mary. 2009. Critical Play: Radical Game Design (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press)

Kang, Jay Caspian. 2022. ‘Ten-year-old Ryan Kaji and His Family Have Turned Videos of Him Playing with Toys into a Multimillion-dollar Empire: Why Do So Many Other Kids Want to Watch?’ New York Times, 9 January, pp. 22-25, 47-49, https://www.nytimes.com/2022/01/05/magazine/ryan-kaji-youtube.html

Klein, Melanie. 1975 [1932]. The Psycho-analysis of Children, trans. by A. Strachey (London: Hogarth)

Konner, Melvin. 2010. The Evolution of Childhood: Relationships, Emotion, Mind (Cambridge: MA: Harvard University Press)

Lancy, David. 2022. Anthropology of Childhood: Cherubs, Chattel, Changelings, 3rd edn (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press)

Opie, Iona, Robert Opie, and Brian Alderson. 1989. The Treasures of Childhood: Books, Toys, and Games from the Opie Collection (London: Arcade)

Pasierbska, Halina. 2008. Doll’s Houses from the V&A Museum of Childhood (London: V&A)

Piaget, Jean. 1962. Play, Dreams, and Imitation in Childhood (New York: Norton)

de Souza e Silva, Adriana, and Ragan Glover-Rijkse. 2020. ‘Introduction: Understanding Hybrid Play’, in Hybrid Play: Crossing Boundaries in Game Design, Player Identities and Play Spaces, ed. by Adriana de Souza e Silva and Ragan Glover-Rijkse (Routledge: London), pp. 1-12

Stallybrass, Peter, and Allon White. 1986. The Politics and Poetics of Transgression (Ithaca: Cornell University Press)

Sutton-Smith, Brian. 1971. ‘A Reply to Piaget: A Play Theory of Copy’, in Child’s Play, ed. by R. E. Herron and B. Sutton-Smith (New York: Wiley), pp. 340-42

——. 1986. Toys as Culture (New York: Gardner Press)

——. 1997. The Ambiguity of Play (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press)

——. 2017. Play for Life: Play Theory and Play as Emotional Survival (Rochester, NY: Strong Museum of Play)

Tannen, Deborah. 2007. Talking Voices: Repetition, Dialogue, and Imagery in Conversational Discourse (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press)

Vygotsky, Lev. 1978. Mind in Society: The Development of Higher Psychological Processes. Ed. by M. Cole (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press)

Willett, Rebekah, Chris Richards, Jackie Marsh, Andrew Burn, and Julia Bishop. 2013. Children, Media, and Playground Cultures: Ethnographic Studies of School Playtimes (London: Palgrave Macmillan)

Winnicott, D. W. 1971. Playing and Reality (London: Tavistock)