3. The Morphogenetic Paradigm: Conceptualising the Human in the Social

© 2023 Basem Adi, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0327.04

In this chapter, I aim to explore the implications of the relational realist approach to the question of personhood. The morphogenetic paradigm, derived from relational realism, approaches this question through the relational and stratified interplay between social- and personal-identity properties. This interdependence accounts for the emergence of personal identity and is fundamental to how referential acts valorise the human element in policies and practices. If we are to valorise the human in the social — as will be discussed in the coming chapters — then it is necessary to explain the relational co-emergence of both. Thus, to enter the dynamics of relations is to identify how social processes mediate the emergence of personal identity.

Inside the relation, we identify the perspective of persons through the properties and powers of ‘internal deliberations’. Starting from the developmental input point of persons, policies and practices are referential acts that become better attuned to the latent reality of the human-in-the-social. Interventions that are developed in conjunction with subjective input, it will be argued, consider the interactive dynamics between personal, collective, and social reflexivity that anchor the process of social morphogenesis. The emphasis on the interactive dynamics of the relations will be investigated in terms of a social ecology that synergistically produces primary and secondary relational goods. Relational goods are vital to sustaining a morphogenetic social order whose parameters are continuously expanded in a transcendental way.

The Interdependence between the Properties of Social Relations and the Emergence of Personal Identity

In the morphogenetic paradigm, an internal conversation links the human and the social. An efficacious internal conversation is pre-supposed by the self’s irreducible subjective authority concerning its wider environment. To investigate personal morphogenesis is to trace its trajectory from the initial sense of self — embodied and emergent from the natural and practical orders — to the development of personal identity. In the coming sections, I will argue that the initial sense of self provides the vantage point from which subjective interiority and authority are made possible. The development of personal identity that arises from the self’s unique vantage point gives the process of personal morphogenesis its irreducible, subjective properties. Any relation that operates relationally, that is, that deals with the problem of social integration in reference to those in relation, should strategise its initiatives from the perspective and trajectory of personal development.

The developmental trajectory of personal identity is a relational property in which internal deliberations are the link between mind and world. These deliberations are characterised by being world-directed and Personal Emergent Properties (PEP). Based on the interplay between personal deliberations and the world, Archer (2003) distinguishes socio-cultural structures (‘context’) from the deliberations and contribution of active agents (‘concerns’) (Archer 2003: 348). The interiority of internal deliberations has the potential to transform the world that cannot be rendered as something impersonal; in other words, internal deliberations are irreducible to the objectivity of third-person ideas:

Because the properties and powers of ‘internal deliberations’ pertain to people, they cannot be expropriated from them and rendered as something impersonal. This would be to destroy their status as a personal emergent property (PEP). Thus the ‘interiority’ of the internal conversation cannot be exteriorised as ‘behaviour’, which could be impersonally understood by all. Similarly, the ‘subjectivity’ of inner dialogue cannot be transmuted into ‘objectivity’, as if first-person thoughts could be replaced by third-person ideas. Finally, the personal causal efficacy of our deliberation cannot be taken over the forces of ‘socialisation’: this would be to replace the power of the person for the power of society (Archer 2003: 94).

Thus, without irreducible interiority, there can be no subjective authority over the forces of socialisation. The properties of subjective interiority generate powers that are relational properties operating between mind and world:

The internal conversation is a personal emergent property (a PEP) rather than a psychological ‘faculty’ of people, meaning some intrinsic human disposition. This is because inner conversations are relational properties, and the relations in question are those which obtain between mind and world (Archer 2003: 94).

The relations between mind and world, the prerequisite of transformative action, is the foundational question of how people distance themselves from their biological origins in a process of social becoming (that is, a trajectory of ongoing development). According to Archer, there are human properties and powers in this middle ground between the two, that is, an irreducible ‘self-consciousness, reflexivity and a goodly knowledge of the world, which is indispensable to thriving in it’ (Archer 2000: 189). The preparation for social becoming affirms an irreducible capability of hermeneutics from a first-person perspective. The importance of this reflexive middle ground is to maintain a clear subjective-objective distinction that upholds an irreducible capability of hermeneutics from a first-person perspective. This first-person perspective, with its irreducible subjective authority and interiority, is logically and ontologically before any social role. To compromise the subject-object distinction is to affirm the human merely as a bundle of molecules engaged in social interactions:

Indeed, it has been argued here that a human being who is capable of hermeneutics has first to learn a good deal about himself or herself, about the world, and about the relations between them, all of which is accomplished through praxis. In short, the human being is both logically and ontologically prior to the social being, whose subsequent properties and powers need to build upon human ones. There is therefore no direct interface between molecules and meanings, for between them stretches this hugely important middle ground of practical life in which our emerging properties and powers distance us from our biological origins and prepare us for our social becoming (Archer 2009: 90).

As inner conversations are relational properties, three residual problems figure in the relation between mind and world. These three problems pertain to the temporal phases of active deliberations (internal dialogues) in which the self adapts its personal identity:

- The generic problem of ‘how can the self be both subject and object at the same time?’ (Archer 2003: 94).

- The analytical problem of who is speaking to whom when considering the temporal question of personal emergence, that is, the inner dialogue and the personal morphogenesis between past, present, and future selves.

- The explanatory problem pertains to how the societal gets into the internal conversation. It explores the necessity of PEP and how the societal, as an order, is then mediated by these powers.

First, I will explore the foundational question of irreducible interiority as a prerequisite for transformative subjective powers. Afterwards, I will examine the implications of the fundamental question of how the three residual problems noted above are conceptualised. I will argue that the idea of reflexivity does not prepare us for our social becoming. Instead, the trajectory of personal morphogenesis in developmental terms — the unique way the indexical ‘I’ is individually sensed as a socially indexed device (Archer 2003: 91) — is what gives internal deliberations their irreducible transformative powers.

The Powers of Internal Deliberation: The Middle Ground between Meanings and Molecules

Subjective moments are expressed through the properties of internal deliberation. The morphogenetic process that explains the emergence of the personal identity starts from the subjective interiority of a fundamental sense of self. The properties and powers of this fundamental sense of self enable the authority of the personal identity as it dedicates itself to a social role. Although this process of deliberation is directed towards the world, it references a constellation of concerns that are emergent from the natural, practical, and discursive orders.1 These orders generate conflicts that require navigation via inner dialogue to establish personal prioritisation and a preference schedule of ultimate concerns. When persons prioritise some concerns over others, a modus vivendi, they arrive at a behavioural outcome when dedicating themselves to a particular path. Archer (2009) develops the DDD scheme to conceptualise this process of prioritisation as a transition from discernment to deliberation to, finally, dedication.

The first-person phenomenon of reflexivity is the starting point in this process and is cognitive rather than merely perceptual (Archer 2003). Persons, that is, must be self-conscious and reflexive selves in order to be capable of hermeneutics. Based on this stratified view, persons are emergent from selves, and the social self is a subset of a broader personal identity that is forged in the DDD process (Archer 2000; 2009). The morphogenetic paradigm acknowledges the trajectory of the personal identity, describing the development of the indexical ‘I’ from being individually sensed to becoming a socially indexed device (Archer 2003: 91). This indexical ‘I’ — the fundamental sense of self — conceives itself independently of a name or other third-person referential device. Subjective interiority, in the self-attribution of mental states, affirms subjective authority over the process and outcomes of reflexive deliberation:

I can conceive of myself quite independently of a name, a description or any other third-person referential device; reflexivity is quintessentially a first-person phenomenon (Archer 2003: 40).

A self-referenced internal conversation — the link between mind and world — is thus a conceptual necessity if internal deliberations are to be efficacious. Unless there is self-knowledge of beliefs, desires, intentions, and memories, then there can be no way to explain how an individual dedicates him or herself to specific role requirements and the manner through which this decision is reached:

Unless people accepted that obligations were incumbent upon them themselves, unless they accepted role requirements as their own, or unless they owned their preferences and consistently pursued a preferences schedule, then nothing would get done in society (Archer 2003: 30).

Subjective deliberation in pursuit of a preference schedule is grounded in the interiority of a fundamental sense of self. This interiority presupposes subjective authority in its dedication to social roles. Before being made public, to confirm irreducibility to the discursive world, internal deliberations must be private. These originate with the transcendental indexical ‘I’. What makes possible the efficacy of the ‘I’ as a subjective authority is reflexivity itself. Reflexive deliberation, a mental activity performed in private, leads to behavioural outcomes about what decisions to take and how to act. The irreducibility of this first-person perspective is thus the ‘transcendentally necessary condition’ (Archer 2003: 31) through which it is possible for the individual sense of self to self-referentially deliberate and dedicate (that is, to commit externally):

reflexivity itself ... [is] a second-order activity in which the subject deliberates upon how some item, such as a belief, desire, idea or state of affairs pertains or relates to itself. By definition, reflexivity’s first port of call has to be the first-person and the deliberation, however short, must be private before it can have the possibility of going public … Hence ’reflexive deliberation’ is the mental activity which, in private, leads to self-knowledge: about what to do, what to think and what to say (Archer 2003: 26).

The properties of internal deliberation establish the centrality of reflexivity in our social becoming. As we shall see later, this also anchors the process of social morphogenesis in persons due to internal deliberations being the link between the mind and the world. In an emphasis on the trajectory of personal identity, with primacy ascribed to embodied practical relations, the objective is to guard against sociological imperialism that emphasises public involvement (Archer 2003: 106).

Primacy is ascribed to the practical relations between meanings (discursive world) and molecules (biological capacities), and it is our reflexive capacity in practical relations that prepares us for our social becoming. Archer’s presupposition is that this position of primacy is necessary to avoid the appropriation of subjective interiority, authority, and efficacy to public involvement.

The Three Residual Problems of the Internal Conversation

In asserting the first-person dimension of reflexivity, Archer implicates three residual problems of the internal conversation, as noted above. These start from the human capacity to be reflexive, which is the foundation of emergent personal identity — the consequences of this developmental progression anchor the processes of double and triple morphogenesis. I will suggest revisions to Archer’s position following a detailed overview of the three problems. The revisions propose that reflexivity, in a developmental sense, is a third-person phenomenon that is actualised according to the unique trajectory of its emergence.

The first residual problem — the generic problem — relates to subjective interiority as a property of internal deliberation. It refers to self-awareness that bends backwards, that is, the alternation of the ‘I’ between states as subject and object. In this interplay, the world-directed experience becomes an object of self-conscious subjective manipulation. Therefore, the relational practical ‘know-how’ that generates these experiences is emergent from an initial being-in-the-world. The subjective manipulation of world-directed experiences bolsters the distinction between self and otherness:

I can self-consciously manipulate the dialectic relationship between self and otherness and, in this very process, I reinforce the distinction between the two (Archer 2000: 130).

Asserting a subjective moment in the dialectic relationship between self and other yields a universal sense of self that necessarily precedes the emergence of the social self. Consequently, there must be efficacy in subjective moments to initiate the internal deliberative process that, after that, dedicates itself externally. Such world-directed deliberation generates a constellation of emergent concerns from the discursive, natural, and practical orders. One must navigate these often-conflicting concerns:

These are concerns about our physical well-being in the natural order, about our performative achievement in the practical order and about our self-worth in the social order (Archer 2003: 120).

Relations to the natural order establish the first point of the self/otherness distinction by grounding the subjective ‘know-how’ emergent from the practical order with its constraints and enablements. The practical order acts as a bridge that secures meaning from embodied engagement in the natural order. Therefore, the irreducibility of the subjective response to societal meanings comes from deliberation about the properties of three ontologically distinct orders. As covered in the previous section, before taking on the social order, the individual human being is both logically and ontologically prior to the social being; social properties and powers are necessarily built upon pre-existing human ones (Archer 2000: 190). Between molecules and meaning is a pivotal role ascribed to the practical order: it is a middle ground that helps to ‘distance us from our biological origins and prepare us for our social becoming’ (Archer 2000: 190). Important human properties and powers emerge in the practical order — namely, a reflexive capacity and knowledge of the world:

There is much more to the human being than a biological bundle of molecules plus society’s conversational meanings. In fact, between the two, and reducible to neither, emerge our most crucial human properties and powers — self-consciousness, reflexivity, and a goodly knowledge of the world, which is indispensable to thriving in it (Archer 2000: 189).

The practical order’s pivotal role does not disappear with the emergence of the propositional. Instead, the practical order continuously sustains society’s conversational meanings via human properties and powers. The sense of self, emergent from embodied practical engagement, is a necessary precursor that sustains an emergent self-concept capable of transforming society’s conversational meanings. Continuity of the sense of self is substantiated by the presence of procedural and eidetic memory that remains beyond the development of self-concept and whose recall is non-discursive. The non-linguistic recall relates directly to a sense of self engaged in its environment — it is through this engagement that there is a self/otherness distinction and a referential detachment inseparable from an understanding of space, time, and causality that are derived from sense data. The continuity of consciousness in both eidetic and procedural memory recalls the sedimentation of accomplished practical acts that form the basis of the ‘habitual body’ and self-identity. The habitual body conveys a past-tense practical accomplishment that enables human beings to contemplate the future. Declarative memory and self-knowledge are developmentally dependent and emergent from this prior constitution. Importantly, any declarative memory-activity never replaces the central role of the non-linguistic component:

memory, far from being some intellectualised representation, is the bodily sedimentation of accomplished acts: it is the ‘habitual body’ which gives our past tense and enables us to contemplate a future, even though our embodied expectations have continuously to be reconciled with the dynamic nature of our existence in the world (Archer 2000: 132).

As the capability of hermeneutics is built on the capacities and powers of the human being, propositional knowledge does not exclusively constitute the direction of the semantic capability. The interplay between subject and object takes into account the properties and powers of objects approached as embodied, practical, and discursive knowledge. All three forms of knowledge shape the situations and circumstances that the subject then deliberates upon as part of their personal projects:

All knowledge entails an interplay between properties and powers of the subject and properties and powers of the object — be this what we can learn to do in nature (embodied knowledge), the skills we can acquire in practice (practical knowledge), or the propositional elaborations we can make in the Cultural System (discursive knowledge). Any form of knowledge thus results from a confluence between our human powers (PEPs) and the powers of reality — natural, practical and social. Thus what have been discussed sequentially are the physical powers of the natural order, the material affordances and constraints of material culture, and, lastly, the logical constraining powers of the Cultural System. However, for the three orders equally, the way in which they affect the subject is by shaping the situations in which he or she find themselves, and their supplying constraints or enablements in relation to the subjects’ projects (Archer 2000: 177).

The second residual problem of the internal conversation (the analytical problem) explores the efficacy of the subjective/objective interplay, considering the dialogue between past, present, and future selves. If the generic problem is concerned with the nature of relations between the subjective and objective from the perspective of world-directed internal deliberations — the basis of what Archer states as the self-conscious manipulation of the relation between self and otherness (Archer 2003: 130) — then the second residual problem deals with the enactment of Personal Emergent Properties (PEP) from the perspective of personal morphogenetic outcomes. The efficacy of the enactment of PEP is expressed in the materialisation of subjective alignment between social and personal identities. The analytical problem, associated with the emergence of the personal identity (subjective alignment), investigates how collective contexts interact with PEP to generate system outcomes, that is, the structure and distribution of positions that the Actor takes up.

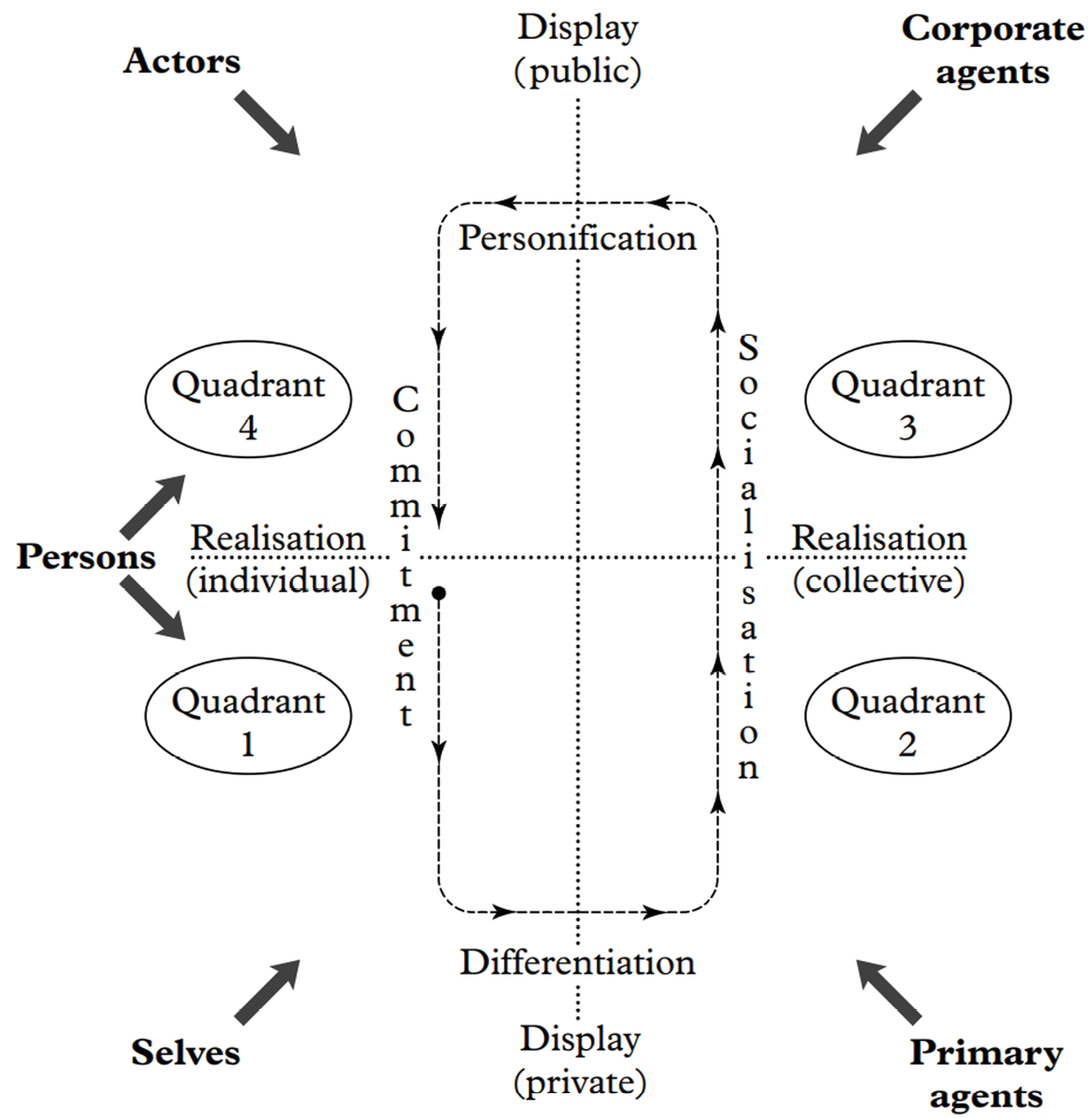

As subjective alignment is the product of internal deliberations, the question is raised of how this alignment can be traced logically and temporally. The answer lies in PEP, which logically pre-supposes the Agent and the social position of the Actor. Human capacities (PEP) enable the individual’s personification of roles based on reflexive adaptation to the properties and powers of collectives they face. These roles are classed as Primary Agency and Corporate Agency (Archer: 2000). Due to the logical primacy of PEP, the efficacy of internal deliberations is temporally charted to changes in both personal identity and society’s normativity. It starts from the irreducible ‘I’ that encounters and deliberates on the properties of its natal context (Primary Agency (Me)). The natal context (Me) of the ‘I’ generates pre-dispositions and influences concerns relating to resources, life chances, etc. Nevertheless, the logical primacy of PEP means it is subjective deliberations that lead either to the reproduction or an attempt to transform the natal context (see quadrants one and two in Figure 3). As a result, the dedication to transform the natal context (Me) leads to the ‘I’ adopting the transformative role of Corporate Agency (We) that seeks to change both personal identity (You) and society’s normativity (see quadrants three and four in Figure 3).

Fig. 3 Realism’s account of the development of the stratified human being (Archer 2000: 260).

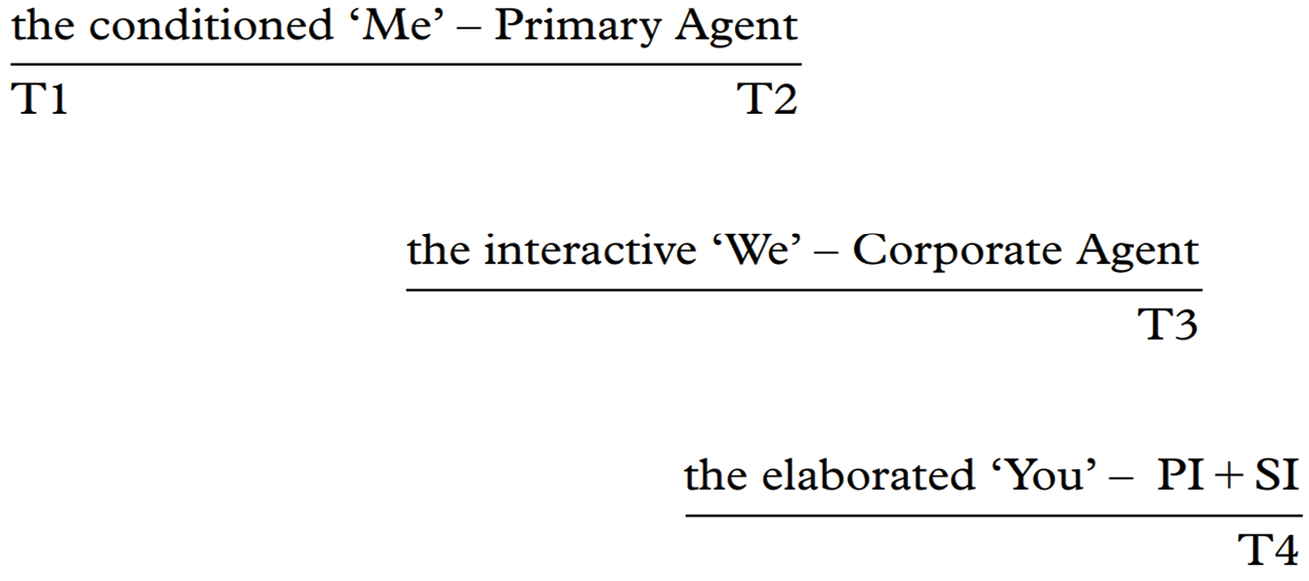

At the point of dedication, the personal identity (You) is subjectively aligned to its social identity (see Figure 4). The logical primacy of the ‘I’ — deliberating on unique concerns generated from its interaction with each relational order — renders social identity a subset of personal identity. Hence without self-identification with the role of Actor, through the properties and powers of Agency, it is not possible for society’s normativity to either reproduce or transform itself. Therefore, the systemic outcomes produced are anchored in the reflexive capacities of persons — their internal conversations — as they become Agents. The explanation of system outcomes follows from the interrelated interaction between personal reflexivity and Agency.

Fig. 4 The emergence of personal and social identity (Archer 2000: 296).

Consequently, the third residual problem — the explanatory problem — looks at the outcomes of interactive dynamics (the second residual problem) in the emergence of social positions and their underlying structures. It aims to explain outcomes vis-à-vis the process of personal morphogenesis and its impact on Agency and Actor. To reiterate, when the ‘I’ is dissatisfied with its initial position — the ‘Me’ — it leads to a commitment to transform the original natal context and, subsequently, society’s normativity. Hence, the co-emergence of the human, Agent, and Actor is examined as part of relational morphogenetic processes that mutually affect each other.

The morphogenesis of Agency is pre-supposed by personal morphogenesis in the personal identity ascribing to itself a social position. In turn, this dedication entails reproductive or transformative social actions that initiate structural or cultural morphostasis/morphogenesis, that is, the reproduction or transformation of the socio-cultural context. In the case of social morphogenesis, Corporate Agents organise to alter the parameters in which collective groups are formed and re-formed. In action, whether to reproduce or transform the social system, the outcome affects the original collective categories. The process in which personal morphogenesis anchors the activities of Agency that, consequently, transforms or sustains the collective categories of Corporate and Primary Agents themselves is termed ‘double morphogenesis’:

This is ‘double morphogenesis’ during which Agency, in its attempt to sustain or transform the social system, is inexorably drawn into sustaining or transforming the categories of Corporate and Primary Agents themselves (Archer 2000: 267).

In an explanatory sense, system outcomes are organically tied to ‘double morphogenesis’ in the interchange between the choices of persons and the actions of Agency. The outcomes produced from this interchange implicate changes in the array of social roles available and the relationship between these roles. Hence, the Actor’s role is anchored in the person vis-à-vis their actions as Agents. The initial role of the Primary Agency is the object of deliberation, which subjects first deliberate upon as part of their constellation of concerns (the first residual problem). The performative enactment of roles is made from this reflexive deliberation and, through Agency, either sustains or transforms society’s normativity:

In living out the initial roles(s), which they have found good reason to occupy, they bring to it or them their singular manner of personifying it or them and this, in turn, has consequences over time. What it does creatively, is to introduce a continuous stream of unscripted role performances, which also over time can cumulatively transform the role expectations. These creative acts are thus transformative of society’s very normativity, which is often most clearly spelt out in the norms attaching to specific roles (Archer 2000: 296).

Therefore, as the process of ‘double morphogenesis’ changes collectives, it also transforms the structure and culture of a society that underpins the roles of social actors. The emergence of social actors is built on the interaction between Primary and Corporate Agents and their outcomes. Consequently, on top of ‘double morphogenesis’, a ‘triple morphogenesis’ can occur in which the social identities of Actors are articulated in relation to the actions of agential collectivities. To restate, the actions of these collectivities are anchored in persons and their reflexive capacities:

In this process, the social identities of individual social actors are forged from agential collectivities in relation to the array of organisational roles which are available in society at that specific time. Both Agents and Actors, however, remain anchored in persons, for neither of the former are constructs or heuristic devices; they concern real people even though they only deal with certain ways of being in society and therefore not with all ways of being human in the world (Archer 1995: 255–256).

As ‘triple morphogenesis’ transforms society’s extant role array (Archer 2000: 295), then the outcomes produced are reflected in systemic parameters that impact the articulation of both Primary and Corporate Agents. Such an increase in the range of roles available means an expanded horizon in which new social movements and interest groups arise (Archer 2000). Hence, the transformation of the socio-structural environment impacts future processes of ‘double morphogenesis’. The morphogenetic explanatory problem views the distinction between Social Agent and Social Actor as analytical and temporal. According to Archer, they are not ‘different people’ but analytically interrelated emergent stratum in which morphogenetic cycles — double and triple morphogenesis — mutually impact each other (Archer 2000). This mutual impact is manifested in the interplay between Agency and socio-cultural context — the outcome produced in this morphogenetic process is observed in the emergent properties and characteristics of active roles that condition future Actors.

Rethinking the Morphogenetic Equation by Extending Reflexivity

Internal deliberations are posited as the anchor of Social Agency. The subsequent emergence of the Social Actor depends on the reflexive reasons of selves that personify roles based on their response to the involuntary ‘Me’. To posit the anchor of morphogenetic processes in persons is based on the need to defend the transcendent and necessary condition of social life in the continuity of consciousness (Archer 2000). This continuity is the foundation of the emergent personal identity and the properties of humanity that recognise and commit themselves to the social. The anchorage of social life in humanity gives the human-in-the-social irreducible powers to internalise and change society’s normativity. As a result, the causal efficacy to change society’s normativity is the implication of putting individual reflexivity as the aprioristic foundation of social concepts.

This section aims to rethink this morphogenetic equation while maintaining and building on its realist starting point, emphasising a stratified conception of the person. Notably, the re-think positions the transcendental reality of the human-in-the-social as both autonomous and dependent on a stratified social reality. At the same time, primacy is not pre-ascribed to the human-in-the-social; instead, it results from the interactive dynamics of the social relation that anchors personal and socio-cultural morphogenesis. As will be discussed in the coming chapters, the rethinking discussed in this section has implications when extending reflexivity to different levels of sociability. Two key points will be proposed as the basis of a rethink of the previously discussed morphogenetic paradigm:

- Archer neglects the psycho-developmental perspective on reflexivity. While self-regulated practical activity is the foundation and sustains reflexivity, I will argue that reflexive capacity is an emergent stratum of meanings comprised of different developmental selves.

- Personal reflexivity is not the anchor but an element of social relations. Following the developmental perspective, reflexivity extends to other aspects of social relations and does not need to be ascribed to an individual identity. As collectivities (Agents) can be reflexive in their own right, the Actor can similarly be both individual and collective.

Regarding the first point, continuity of consciousness initiated in practical activity in the material world generates an irreducible trajectory of experiences. The reflexive space between molecules and meanings, according to Archer, generates the earliest concerns navigated by an emergent personal identity. This space makes the enactment of reflexivity irreducible to both the biological bundle of molecules and discursive meanings. The pivotal role of practical world-directed experiences renders speech acts as self-experiences. As reflexivity is made a logical necessity to enact the self-experiences of the individual identity, its developmental dimension is inadvertently neglected.

Indeed, the subjective capacity to reflect on the flow of experiences (the first residual problem) includes practical knowledge of the world. However, this world-directed reflection is an emergent stratum of the initial perspectival ownership of experience — the first personal presence of experience (Zahavi 2013). The perspectival ownership makes the mind/body ‘I’ perceive itself within the ubiquitous first-personal givenness in the multitude of changing experiences. Thus, the minimal self is between a biological bundle of molecules and discursive meanings. Further, it is the sense of self that unites world-awareness and self-experience. According to Zahavi (2009), the minimal self exists in the subjectivity of experience that is, at the same time, world-directed:

The minimal self was tentatively defined as the ubiquitous dimension of first-personal givenness in the multitude of changing experiences. On this reading, there is no pure experience-independent self. The minimal self is the very subjectivity of experience and not something that exists independently of the experiential flow. Moreover, the experiences in question are world-directed experiences. They present the world in a certain way, but at the same time they also involve self-presence and hence a subjective point of view. In short, they are of something other than the subject and they are like something for the subject. Thus, the phenomenology of conscious experience is one that emphasises the unity of world-awareness and self-experience (Zahavi 2009: 556).

It is between world-awareness and the minimal self that the subjective/objective interplay unfolds. The capacity to deliberate on changing experiences requires a semantic awareness that is contingent on the lived circumstances of the collective (Primary and Corporate Agency). At the same time, the experiential flow always returns to the bio-physical consciousness (Donati 2011) that provides self-presence with its non-arbitrary direction in personal deliberations.

The interplay between the non-arbitrary and contingent gives personal identity crucial human properties and powers. Moreover, the interplay emphasises the developmental dimension of personal identity through the subjective integration and appropriation of lived experience. The process of subjective integration considers past experience as the sense of self directs itself towards objects. Due to being emergent from differentiated minds/bodies, the genesis of practices is understood through developmental stages that impact how past experiences are filtered when confronting collectivities. It is the genesis of self-present practice, grounded in the process of subjective integration, that disinters human properties and powers from the logic of practices that inhere in collectivities.

The developmental genesis of reflexivity — with its necessary capacities to deliberate on concerns — comprises a continuum of developmental selves. There are five different stages in the development of the conceptual self that make reflexivity possible (Neisser 1988). First, the ecological self, appearing in the earliest infancy, is a primitive awareness that the self is practically embedded in its environment and consists of self-regulated bodily interaction with external objects. The awareness of the self in the world (biophysical consciousness) leads to the interpersonal self, which extends the ecological self to respond and coordinate its actions with others. Consequently, the self mutually co-perceives objects in its environment. The ecological self and interpersonal self should be viewed as inextricable, since ‘awareness of the interpersonal is almost invariably accompanied by a simultaneous awareness of the ecological self.’ (Neisser 1988: 395)

The ecological and interpersonal stages represent two aspects of the implicit self from which children develop an implicit (pre-conceptual) self-knowledge that is inherently reciprocal to their environment (Rochat 2001). The extended self is memory-based, giving the continuous sense of self a temporal place in the world. It is an autobiographical memory that draws on past experiences as it confronts the present. The extended self appears in childhood — solidified at age three — and gradually takes an important role as individuals grow older. By being able to locate the ecological self through integrating remembered experiences to the present, a life narrative is constructed. The ‘I’ can look back during present interactions to draw out future behaviour (Neisser 1988: 46).

Later, the private self is the stage in which the infant understands its experiences as demarcated from the world, that is, one acquires a sense of exclusivity of his or her experiences. Subjective interiority is introspective and enables the self-concept (the semantic self) by rendering its dedication independent of external circumstances. The private self represents a shift from extrospection to introspection and becomes the basis of the reflexive capacity to deliberate on the world from the first-person perspective. This deliberation facilitates personal planning to achieve personal goals.

The capacity to mentally approximate (reflexivity) represents a shift to the conceptual self (Rochat 2010). In the conceptual self, subjective interiority self-consciously integrates its experiences — emergent from practical activity in a biophysical environment — referencing world-directed experiences. The self-conscious attempt to integrate experiences represents a shift to the explicit self that is based on the third-person perspective (public mediation of experience). In this stage, emergent from the implicit self, the explicit self is made possible through others. Social roles are socio-cultural emergent properties that make possible reciprocal exchanges between the implicit and explicit self.

Personal deliberations that figure in the subject/object interplay (the second residual problem) are possible after developing the conceptual self. In the integration process between the first-person and third-person perspectives, there is the emergence of personal identity. The developmental stages that lead to the conceptual stage, according to Neisser (1988), mean other forms of self-knowledge — the ecological, interpersonal, and private selves — all are represented in the conceptual self:

Thus our self-concepts typically include ideas about our physical bodies, about interpersonal communication, about what kinds of things we have done in the past and are likely to do in future, and especially about the meaning of our own thoughts and feelings. The result is that each of the other four kinds of self-knowledge is also represented in the conceptual self (Neisser 1988: 54).

The four kinds of self-knowledge are represented in the conceptual self, confirming a stratified conception of personal identity. In each of these selves, distinct variations between individuals impact the development and qualitative enactment of the reflexive capacity and its mental approximations (the conceptual self). Consequently, the unique trajectory of personal morphogenesis is identified in the developmental process — the interplay between the non-arbitrary and contingent — that implicates the logical necessity of an irreducible subjective interiority with its capacity to mentally approximate.

As the temporal interplay between the existential self (the ‘I’) and its collective context is built on and sustained by different kinds of self-knowledge, the explicit sense of self is not just a public matter. In the emergence of subjective alignment, the process in which mental approximations of world-directed experiences are integrated means there is always an element of loss as it is filtered through the collective context (‘Me’ and ‘We’). The continuity of consciousness means novel experiences require a reflexive imperative in which the non-arbitrary dimension of the self can integrate experiences based on past episodes of personal morphogenesis.

It is the process of ‘gain and loss’ of experience — the genesis of subjective alignment between the implicit and explicit self — that potentially transforms the personal identity and the role it subsequently adopts (Gallagher and Zahavi 2012). The ability to form self-concepts is developmentally tied to reflexivity, but it can only operate effectively with the existence of mechanisms described above that enable bodily awareness, practical engagement with others, autobiographical memory that draws on past experiences as it confronts the present and the ability to plan practical activities.

Second, as reflexivity is identified with meaning-based deliberation (the formation of self-concepts), then it is possible to extend reflexivity to include any form of meaning-based deliberation that utilises society’s conversational meanings.2 Thus, it is identified with any activity that seeks to manage the outcomes of morphogenetic processes. As Donati observes, reflexivity is a property that extends to other aspects of the social:

The ambivalence of reflexivity is redefined as a differential property/ability possessed by actors, or networks, or systems with regard to their need for managing the outcomes of morphogenetic processes (Donati 2011).

In the personal management of social identities, the internal conversation manages reciprocal exchanges between the implicit and explicit selves (personal reflexivity). After that, when this personal reflexivity dedicates itself to an explicit self, its powers extend to the activity of collectives.

The interaction between individuals and collectives gives social networks new properties and powers. This extended reflexive process’s interactive dynamics of sociability result in social reflexivity, the effects of which are seen in socio-cultural structures. Consequently, the social reflexivity of social networks produces relations at the system level wherein direction is an effect of the interactive dynamic between personal, collective, and social reflexivity. An emergent effect is that the system’s internal parts are configured by temporal cycles of morphogenetic change. The configuration of elements impacts future patterns of sociability and how the system responds to future interactive dynamics. That system features adapt their operation to the contingencies of interactions is due in part to the inbuilt capability of the system to reflect on itself within the morphogenesis process.3

Based on the extension of reflexivity beyond the personal, the anchor of double and triple morphogenesis (the third residual problem) is the interaction between personal reflexivity and the reflexivity of social networks. It is not the relationship between personal reflexivity and collectives that anchors triple morphogenesis. Instead, the dynamic between personal and collective reflexivity within relational networks anchors system outcomes (the properties and array of social roles). Personal reflexivity is an essential element of this interactive dynamic; as a person adopts the role of the Actor (the explicit self), he or she initiates interaction within collectives.

The implications of an extended understanding of reflexivity will be explored in the coming chapters in the context of post-functionalist approaches to education. Specifically, I will look at the design and operation of curriculum and assessment from within reciprocal exchanges of proximity. A system in which actors, networks, and systems are not regulated but enabled to operate meta-reflexively valorises the transcendent (the human-in-the-social) dimension of relations. Within such a system, fostering the human-in-the-social becomes the purpose of education. Being attuned to the personal in relationships ensures integration starts from making relations reflexive in a transcendental way (Donati 2011). Against the artificial sanctioning of ‘excellence’, relational reflexivity is actuated in practices designed to develop all students in response to their unique subjective input points.4 Thus, input points become the referent, and education practices are evolving referential acts to better understand this referent.

Conclusion

In this chapter, I investigated the question of personhood and the emergence of personal identity. The rationale behind this investigation was to present the morphogenetic paradigm that explains the emergence of the human in relation to broader natural, practical, and discursive orders. Thus, to provide an account of this emergence, it is necessary to enter the relational dynamics that generate concerns which need to be navigated by individuals. This means taking the perspective of persons as they deliberate on concerns as part of their developing personal identity. When referential acts proposed as part of policy and practices start from the dynamics of relations that impact the development of the nascent personal identity, they become attuned to the reality of human potentiality. The potentiality of the human is in the development of Personal Emergent Properties (PEP) as part of the morphogenetic trajectory of personal identity.

Both logically and ontologically, conceptually affirming the efficacy of PEP necessitates the primacy of reflexivity in the form of personal deliberations. Reflexivity as a first-person phenomenon is cognitive rather than merely perceptual. Before behaviour is manifested as personal dedication, it is an inward deliberation upon the constellation of concerns emergent from the natural, practical, and discursive orders. The reflexive deliberations of persons — represented in the indexical ‘I’ — is the transcendentally necessary condition from which dedication to social roles becomes possible. Based on the input points at different stages of personal morphogenetic cycles (the analytical problem), it is possible to account for personal identity’s past, present, and future emergence.

As Personal Emergent Properties (PEP) are inherently relational, personal deliberation and subsequent dedication pre-suppose Primary and Corporate Agency. Human capacities logically pre-suppose Agency and the personification of the role of Actor, and double and triple morphogenesis are anchored in reflexive internal conversations. Morphogenetic cycles are instigated by changes in personal identity that then generate collective roles leading to the transformation or reproduction of system mechanisms.

This chapter proposed a revision to the morphogenetic paradigm that builds on its stratified view of social reality in which structure and Agency intertwine and mutually redefine each other. While still working from the same ontological pre-suppositions, the revision takes a developmental perspective to understand reflexivity and its emergence. Importantly, its revision, taking a developmental perspective, views reflexivity as a discursive capacity that is part of an irreducible trajectory. In this personal trajectory, subjective integration — the unification of self- and world-awareness — is affected by pre-supposing developmental selves. The differentiated way developmental selves produce and sustain the conceptual self (in which reflexivity is enacted) leads to different mental approximations and the first-person presence of world-directed experience.

As reflexivity is viewed as any meaning-based deliberation, it extends to Agency (collective reflexivity) and social networks (social reflexivity). Both collective reflexivity and social reflexivity are pre-supposed by the development of personal reflexivity and the enactment of PEP in the first instance. However, once developed, the management of the morphogenetic process is a reciprocal synergy between levels of the social. It includes relations of proximity to wider networks that impact the reflexive direction of relations. Hence, the interactive dynamics of different levels of reflexivity — personal, collective, and social reflexivity — anchor morphogenetic cycles. In a relational order — one that is underpinned by a relational symbolic code — the system operates ex post facto in response to the noted morphogenetic processes.

The proposed idea of meta-reflexive management of morphogenetic processes, which operates within different levels of sociability, is investigated in the coming chapters. What is specifically explored is the idea of a post-functionalist approach to education which starts from developmental input points. It is an inclusive approach to practice and provision that anchors reflexive activity in the interactive dynamics of sociability from which the latent reality of the human-in-the-social is emergent. In contrast to the artificial sanctioning of learning that occurs in system-based approaches to credentialing (and neglects developmental input points), the aim is to ensure the potentiality of the human defines the parameters of sociability. If reflexive processes are to operate based on the human/non-human distinction, then practices cannot be static. As a result, an evolving and adaptive judgmental rationality is directed at the human-in-the-social.

1 Each of these orders generates distinct concerns that need to be navigated and reflexively configured by an emergent personal identity. According to Archer, ‘A distinct type of concern derives from each of these orders. The concerns at stake are respectively those of “physical well-being” in relation to the natural order, “performative competence” in relation to the practical order, and “self-worth” in relation to the social order’ (Archer 2011: 88).

2 To ensure the efficacy of subjective properties and powers, Archer identifies reflexivity as a property of people (2009). However, when reflexivity is rethought as meanings-based activity, it can take a collective dimension to include the actions of collectives (collective reflexivity of Agency) and the internal dynamics of social networks as social reflexivity. The reciprocal interaction between individuals and Agency impacts the mode of reflexivity of social networks. In turn, the configuration of social networks, considering morphogenetic cycles, impacts the reflexive direction of future interactions. Specifically, the sociability sources in these networks — for example, trust, reciprocity, and collaboration — are expressions of interactions that enhance or depreciate social value. Hence, social networks that operate meta-reflexively possess their powers through the relational goods produced by the actions of Agents and Actors. Consequently, considering the ontology of social networks, social reflexivity is inherently relational as it is enacted mutually through contingently generated reciprocal action that is part of the relationality that constitutes social reality (Donati 2011).

3 System characteristics are social mechanisms that are morphogenetic outcomes of reciprocal interactions. As outcomes, they stabilise social networks and conduct future interactions. However, as outcomes of reflexive human activity, they are reflective rather than reflexive. In the case of systemic social mechanisms, reflectivity is the self-referential capability of the system to adapt its characteristics in response to reflexive activity. Reflexivity, on the other hand, is a semantic activity that starts inwards but expands relationally in its operation (Donati 2011). The manner in which the system operates — as a formalised condensation of social networks — is dependent on the properties and modes of reflexivity that exist in the dynamics of sociability from which it is emergent. Therefore, the direction of the system’s inbuilt reflective capability is recursively explained by morphogenetic cycles.

4 The student input point refers to the learner’s developmental stage at the beginning of a learning cycle. The goal of registering input points is to maintain a coherent learning trajectory for students to ensure vital developmental milestones are not missed before starting the next cycle.