3. Public Investment in Germany: Squaring the Circle

© 2022 Katja Rietzler and Andrew Watt, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0328.03

3.1 A Decade of Investment

In Germany the huge investment needs for the modernisation and transformation of the economy following decades of under-investment in infrastructure and other public goods have become a prominent topic, as already discussed in previous issues of the European Public Investment Outlook (Dullien et al. 2020; Rietzler and Watt 2021). In its coalition agreement of November 2021, Germany’s new government of social democrats, greens and liberals acknowledges Germany’s tremendous investment needs and promised “a decade of investment” (SPD et al. 2021). Under the title “Mehr Fortschritt wagen” (Dare to make more progress) the coalition agreement sets out ambitious spending plans that go beyond the modernisation of Germany’s infrastructure and speeding up the decarbonisation of the economy. They include among other things a replacement of the Hartz-IV social benefit system, a general transfer to ensure the subsistence level for children (“Kindergrundsicherung”), support for additional housing, and federal support to address the problem of over-indebted municipalities. The latter is particularly noteworthy as in Germany’s federal system, it is local authorities that are responsible for more than a third of total public investment and almost 60 % of public construction investment.

At the same time the coalition government is determined to return to the German debt brake―which like the European rules is currently suspended―in 2023 without reforming it and without raising taxes. In both cases the liberal party, FDP, the coalition partner with the least seats in the Bundestag, but whose leader is the new finance minister, has had its way. At first sight it seems nearly impossible to increase spending substantially with no additional public borrowing or tax increases. The coalition government hopes to square the circle by resorting to substantial operations using off-budget funds and reserves. The federal government still has reserves built-up from surpluses before the pandemic (“allgemeine Rücklage”) amounting to €48 billion. It has recently taken on new debt, making use of the suspension of the debt brake, and transferred €60 billion to the Energy and Climate Fund (EKF), which is to be renamed Climate and Transformation Fund (KTF). In total the EKF/KTF will have reserves of almost €80 billion at the end of 2022 which can be spent in the years from 2023. At the same time more use is to be made of public companies and off-budget entities, such as the state railway company, the federal real estate agency (BImA) and the German development bank KfW. An additional scope of about €6 billion results from postponing the repayment of the federal debt incurred in the pandemic until after 2027. The coalition agreement also foresees that additional fiscal room for manoeuvre will be created by reforming the cyclical adjustment mechanism in the debt brake.

The German debt brake differs in several respects from the European fiscal rules, the two most important being the scope and the deficit concept. Whereas the European Fiscal rules focus on the total government sector as defined in the ESA 2010, the German debt brake includes the core budgets and selected off-budget entities. Unlike the Stability and Growth Pact, the debt brake focuses on net new debt instead of the fiscal balance. As a consequence, operations with reserves and off-budget entities can be used to enable additional borrowing while at the same time complying with the debt brake. The IMK estimates the additional room for manoeuvre created by the agreement between the three parties to be in the low three-digit billions in the legislative term ending in 2025 (Dullien et al. 2022a), if the supply of additional funds to the EKF/KTF under the escape clause of the debt brake is not ruled unconstitutional by the federal constitutional court (Bundesverfassungsgericht) in a lawsuit filed by the conservative CDU/CSU group in the Bundestag. As the additional funding of the EKF/KTF accounts for a substantial share of the additional scope for public investment, a negative court ruling would place the “decade of investment” at risk. The cycle of greater investment, but no additional borrowing or taxes could no longer be squared.

3.2 Some Progress since 2019

“A decade of investment” is exactly what an influential report assessing the requirement for public investment had called for (Bardt et al. 2019) It put the public investment backlog at €457 billion over ten years, or 1.3% of GDP per year, a finding endorsed by trade unions and employers alike and considered plausible by the scientific council of the German Ministry of Economy and Energy (Wissenschaftlicher Beirat beim BMWi 2020). However, the report requires an update, particularly because climate policy has become much more ambitious since 2019. The EU’s target for the reduction of greenhouse gas emissions until 2030 has been raised from 40% to 55%. Accordingly, Germany aims to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 65% before 2030 (instead of 55%). This implies that the transformation of the German economy towards zero or even negative emissions will have to be accelerated tremendously. Investment in the decarbonisation of production, housing and transport will have to be frontloaded, leading to higher spending requirements in the short term.

A recent study by Krebs and Steitz (2021) estimates that €460 billion will have to be spent on public investment in climate protection and related fields alone in the coming ten years. As this more recent study excludes a large part of the public investment requirement, like overcoming the investment backlog at the local level, which is estimated at €159 billion (Raffer and Scheller 2022), the overall requirement is significantly higher. It makes sense to combine the results of the two studies by Bardt et al. and Krebs and Steitz. Allowing for the substantial overlap of more than a third (about 0.5% of GDP) between them, a total requirement emerges of approximately 2.1% of GDP per year. Only part of this spending is direct public investment according to the national accounts’ definition; a substantial share consists of support for private investment in the socio-ecological transformation of the economy via investment grants and other instruments. Out of the € 460 billion that Krebs and Steitz (2021) identify as investment spending needs over ten years, €200 billion are support to private investment.

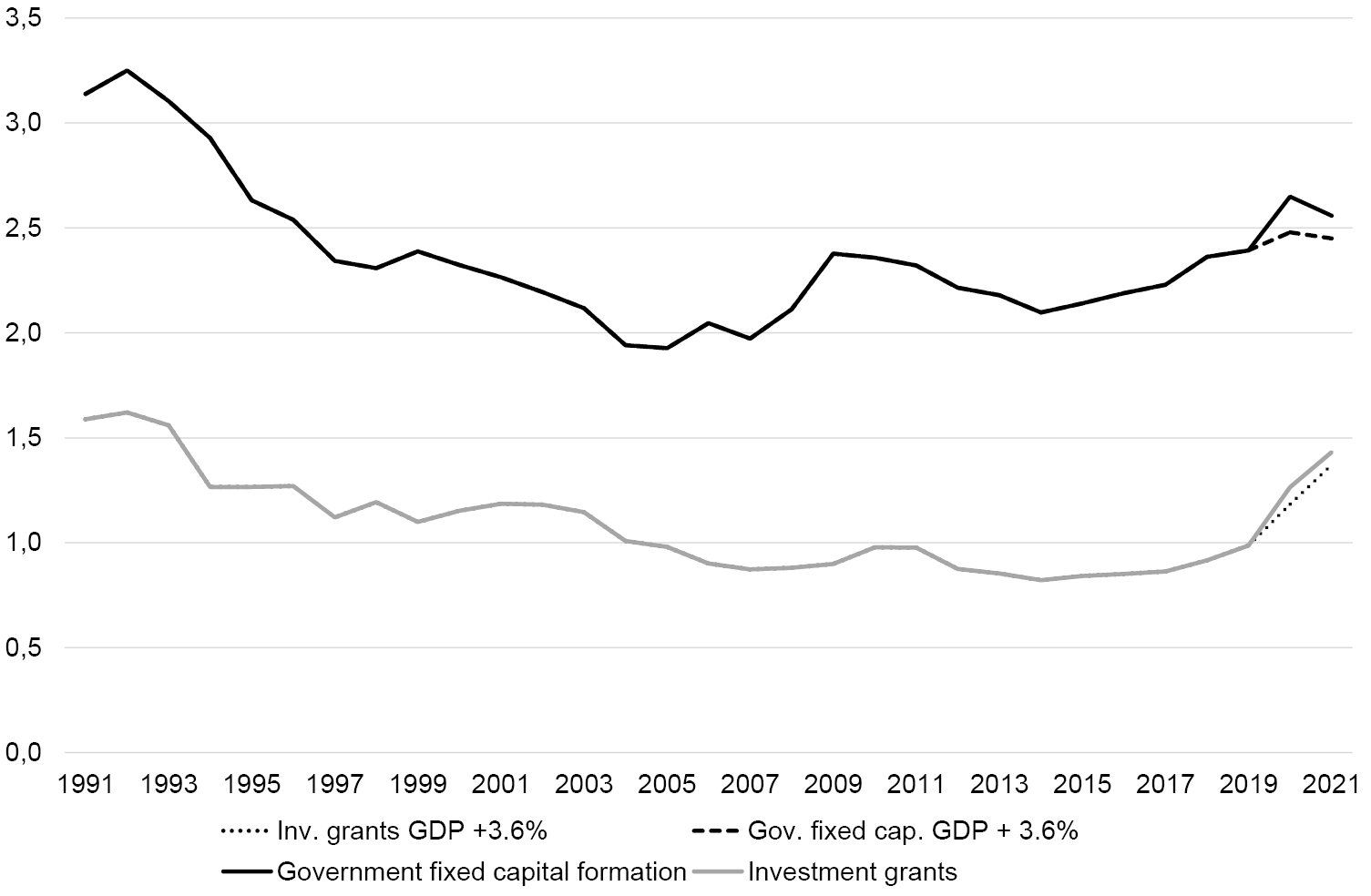

Since the publication of Bardt et al. (2019) German public investment spending has continued to increase not only in absolute terms, but also as share of GDP. The public investment ratio has risen by 0.2 percentage points and investment grants as percentage of GDP have even increased by 0.4 percentage points (Figure 3.1). Part of the increase can be explained by the fall in nominal GDP due to the pandemic, however. If nominal GDP had risen in 2020 and 2021 as in the ten years to 2019―i.e., by 3.6% annually―the ratios would be lower, particularly in the case of direct public investment. Most progress in government investment spending has come via the support for investment in other sectors through investment grants. They include, among others, payments from the federal government to the state railway company and support to non-financial corporations by local governments.

Fig. 3.1 Public Investment and Investment Grants (% of GDP).

Source: Destatis (national accounts), calculations of the IMK.

Given the recent higher ratio of investment spending, it can be argued that some 0.4 to 0.6 percentage points of the additional requirement have already been reached; this higher investment ratio would need to be sustained in order to reach a sufficient level of investment. At the same time, the studies mentioned above, both following a bottom-up approach, do not include all public investment needs. The pandemic has shown that the health sector requires massive modernisation investment, which neither study mentions. In addition, climate protection and adaption spending in local communities probably requires substantial spending beyond the amounts gauged in the studies, if climate targets are to be achieved; neither study includes energy efficiency of public buildings at the local level, for instance. The Ministry of Economy and Energy (BMWi 2018) estimates the number of properties owned by local communities at 176,000 and states that the local level consumes two thirds of the public sector’s final energy use. In addition, climate adaption requires modernising civil and flooding protection and numerous other climate adaption measures (Rietzler 2022a). Thus, as a very rough estimate it can be concluded that investment requirements (including investment grants to the private sector) still amount to sustained spending of 1.6–2.1% of GDP, or roughly €600–800 billion over ten years.

3.3 War in Ukraine and High Inflation

Just a few months after the government was formed, it faced an unexpected and severe additional challenge in the form of the war in Ukraine and surging energy prices that distract it from its original agenda. From spring 2022 Germany, like other European countries, has experienced monthly inflation rates at a level not seen since the 1950s. Private consumption expenditure was burdened by surging energy prices in the very moment when pandemic-linked restrictions were lifted, which should have supported a recovery of consumer spending. The government saw an urgent need to cushion the effects of high energy prices, particularly for those most affected. Within two months the government launched two “relief packages” amounting to more than €30 billion. Overall, the packages are socially balanced with a substantial share of one-off payments both to recipients of transfers as well as employed persons and households with children (Dullien et al. 2022b). At the same time roughly 10% of the total relief is provided via a temporary reduction of the energy tax on transport fuels, which counteracts the national carbon price introduced in 2021 and largely benefits households with higher incomes and substantial fuel consumption (Rietzler 2022b).

Meanwhile a third relief package has been announced. It consists of more than twenty individual measures including one-off payments to pensioners, income tax reductions as well as an electricity price cap. Although a lot of details remain to be specified, the government puts the overall amount at €65 billion, twice that of the previous two packages. A partial cap on household gas prices is now being specified in detail after group of experts submitted its final report (ExpertInnen-Kommission Gas und Wärme 2022). Depending on its exact parameters, this cap would imply additional fiscal costs of around € 90 billion. Additionally, the major gas importer Uniper was taken into state ownership to prevent its insolvency. Substantial unforeseen public investment is needed, notably to provide, as quickly as possible, a facility to import liquified natural gas and more generally to accelerate the transition away from fossil fuels, specifically those imported from Russia. Beyond the first three relief packages the German government is making an additional € 200 billion available.

As the debt brake is still suspended in 2022, debt finance of the relief measures via an extra-budget is not a problem. However, more than half the measures stretch beyond 2022. At the same time forecasts for economic growth have been substantially revised downwards, putting pressure on government revenues (Dullien et al. 2022c). Under such conditions, unforeseen when the coalition agreement was signed, a further extension of the suspension of the debt brake looks increasingly likely.

The war in Ukraine has also returned military spending to the political agenda. Germany has committed itself to increasing military spending substantially in the coming years so as to meet its NATO commitments. On the one hand military spending in the regular budget is to increase by 7.3% or €3.4 billion according to the budget plan for 2022. In addition, an off-budget fund of €100 billion (Sondervermögen “Bundeswehr”) has been created to finance increased military spending in the coming years. As it is to be debt-financed, its implementation required a change of the constitution, which took place with wide parliamentary support. In the short run, this arrangement implies that military spending, of which a large part will be classified as investment in the national accounts, can be increased alongside the investment for other purposes mentioned above and will not crowd out the latter. However, the debt of €100 billion is to be repaid “over a reasonable period” starting in 2031. The repayment will then coincide with the repayment of the federal debt incurred under the pandemic over thirty years beginning in 2028, and this will then inevitably create tensions with other spending priorities in the longer run.

3.4 Stability Programme Suggests that Additional Investment Is Mostly Military

Whereas the coalition agreement contains no quantified fiscal parameters and the government’s use of reserves and off-budget funds and entities lacks transparency, the German Stability Programme 2022 submitted under the European Semester provides a complete picture with projections for the whole government sector based on the national accounts. The Stability Programme announces a substantial increase both of direct public investment and investment grants to other sectors from 2022 onwards. The combined increase in the period from 2021 until 2023 adds up to roughly 0.8 percentage points of GDP (Table 3.1). At first sight this seems impressive as it would be more than one third of the investment spending requirements discussed above within just two years.

Table 3.1 German stability programme (% of GDP)

|

Year |

2019 |

2020 |

2021 |

2022 |

2023 |

2024 |

2025 |

2026 |

|

Government sector gross fixed capital formation |

2,4 |

2,6 |

2,6 |

3 |

3 |

3 |

2 ¾ |

2 ¾ |

|

Additional military investment |

- |

- |

- |

0,4 |

0,5 |

0,5 |

0,5 |

0,5 |

|

Government sector investment grants |

1,0 |

1,3 |

1,4 |

1 ½ |

1 ¾ |

1 ¾ |

1 ¾ |

1 ½ |

Source: Federal Ministry of Finance (2022), pp. 54, 57, Additional information provided by the Federal Ministry of Finance, Destatis.

However, closer analysis reveals that the additional investment spending is of the same order of magnitude as planned additional military investment. Furthermore, government gross fixed capital formation is expected to decline again relative to GDP in 2025 and 2026, while the share of military investment is expected to remain unchanged. It must be taken into account that data on annual additional military investment in the German Stability Programme 2022 reflect a “technical assumption”. Actual spending may be spread less evenly across the years of the planning period. Most probably, additional military spending will remain significantly below 0,4 % of GDP in 2022 and 2023. According to the draft federal budget, which is currently being discussed in parliament, military spending from the off-budget fund will be €8.5 billion or 0.2% of GDP in 2023.

As discussed in last year’s report, the previous German government had announced substantial additional investment as part of its stimulus and future package. Now the coalition government of social democrats, greens and liberals has promised a massive increase of public investment. However, this is not reflected in the government’s Stability Programme 2022. The Stability Programme contains no increase of direct public investment beyond additional spending on military procurement. According to the programme, non-military direct public investment will be even lower as a share of GDP in 2025 and 2026 than it was in 2021. This major contradiction is partially explained by the fact that substantial public funds will be made available to support private investment.

3.5 The Critical Issue of Local Government Financing

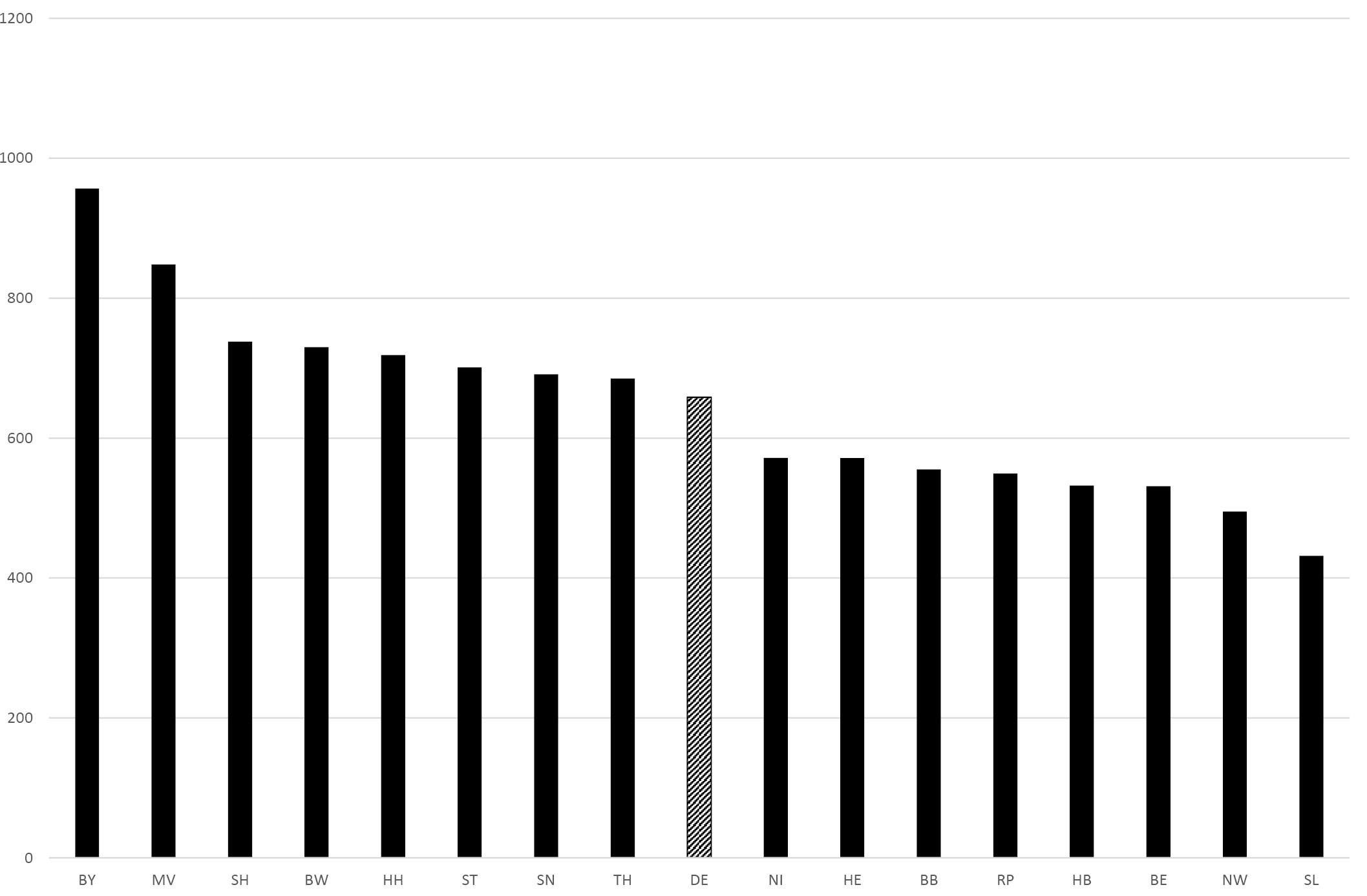

Assessing public investment in Germany, one has to look beyond federal investment spending. Local communities play a particularly important role. They are responsible for school buildings and local roads, which account for a large share in the public investment backlog. In addition, they also play an important role in local public transport and face additional investment needs for climate protection and adaption. Based on the studies mentioned above, a conservative estimate puts local-authority investment needs at €250–300 billion out of the total of €600–800 billion. To enable local governments to invest enough, long-standing problems of municipal finances have to be solved. One issue is a large burden of liquidity credits piled up primarily in the early 2000s. Some federal states have already implemented their own support programmes for indebted local authorities, but the federal government needs to step up, as a large part of the debt incurred is a consequence of federal legislation transferring more and more responsibilities to the local authorities without providing the necessary funding. At the same time these problems must be prevented from recurring. Additional responsibilities for the municipalities require corresponding funding. Local investment spending differs very widely between regions. Figure 3.2 shows tangible investment of state and local government investment governments in the German states (“Länder”) per inhabitant for the year 2021. In Bavaria (BY) the state and local government levels taken together1 invested €957 per inhabitant, the comparable figure for Saarland (SL) was only €431, less than half. Although there might be differences in the price level and the scope of outsourcing to the private sector, the difference is striking and persistent. During the last ten years Baden-Württemberg, Bavaria, Saxony and in most years Hamburg exhibited public investment above the German average, whereas public investment in North Rhine-Westphalia and Saarland was the lowest among all states excluding the three city states. Besides a weak revenue base, high social spending is a major contributor to low municipal investment (Beznoska and Kauder 2020; Bremer et al. 2021). It has also contributed to the high liquidity credits. Although the federal government has gradually increased its support of local social spending, further improvements are necessary (Rietzler 2022a).

Fig. 3.2 Tangible Investment of Local and State Governments in 2021 (Euro per inhabitant).

Source: Destatis, Fachserie 14 Reihe 2, Statistische Ämter des Bundes und der Länder, calculations of the IMK.

The foreseen return to the debt brake in 2023 will make it more difficult to increase public investment―not so much at the federal level, where the use of loopholes created additional fiscal space, but at the regional and local level. Whereas the federal government is allowed to incur some additional new debt even under the debt brake, the states must stick to a strict zero (structural) debt limit. In addition, the states start paying off the additional debt incurred in the pandemic much earlier than the federal government and some have chosen a short repayment period. This is likely to have repercussions for local finances.

3.6 The German Recovery and Resilience Plan

As discussed in detail in last year’s EPIO, Germany submitted its application for RRF funding―the Deutsche Aufbau und Resilienzplan, DARP—on time in 2021. Meeting the requirements in terms of the proportions devoted to decarbonisation and―by a long way―digitalisation, and respecting country-specific recommendations, the plan was swiftly approved by the EU Commission and the Council. Because of the redistributive nature of the RRF, which favours lower-income countries and those more severely affected by the COVID-19-related crisis and the fact that Germany’s public debt sets the interest-rate benchmarks in Europe and thus it had no incentive to avail itself of RRF loans, Germany’s national RRF Plan is of limited macroeconomic relevance. The overall volume of the DARP is around €25 billion (around 0.7% of annual GDP) to be spread over three years. Germany also faces less stringent constraints from EU fiscal rules than many other countries, such that it is of limited importance compared to the national spending programmes discussed in this chapter. As last year’s analysis showed it mainly served to bring forward and expand projects that were due to be implemented under national investment and climate-related initiatives.

One of the consequences of the limited size of the DARP―and thus also public interest in the details―compared to countries such as Italy, which have taken advantage of loans and sought to front-load investment and reform initiatives, is that, at the time of writing, very little information has been made available on the progress of DARP projects. As early as August 2021 pre-financing was disbursed, amounting to 9% of the total (€2.25bn). As, by its nature, pre-financing is not conditional on member states having achieved agreed milestones (and thus requiring reporting on results achieved) this has not generated publicly available data. As of September 2022, the European Commission’s RRF Scoreboard does not indicate that any further disbursements have been made nor milestones achieved. While the exigencies of coping with the impact of the Ukraine war offer a plausible explanation for delays, it is noteworthy that, by the summer, Italy, for instance, had already received two payments and submitted a claim for a third, for a total of around €66bn.

The European Commission is conducting a comparative review of progress by the member states in implementing their national plans based on an agreed set of common indicators. Countries were to report by February 2022 and a cross-sectional analysis was to be made available in April. However, difficulties in obtaining fully comparable information from all member states have delayed publication of this information.2

In short, an assessment of the national RRF plan’s actual―as opposed to potential―contribution to meeting Germany’s public investment needs will have to await next year’s EPIO.

3.7 The Way to Sufficient Investment Spending

Compared to the additional public investment needs, the amounts that can be expected to be forthcoming will clearly be insufficient, particularly concerning the government sector’s own investments. It may be easier in the short run to increase investment grants to the private sector, but direct public investment (excluding military spending) also needs to increase very substantially and in a sustained manner. An increase of the required magnitude requires, of course, not only the provision of financial resources, but also sufficient supply-side capacities, both in the business sector and in public sector planning departments. In recent years Germany has faced significant bottlenecks in the construction sector that slow down public investment projects and cause sharp price increases (Scheller et al. 2021), the price deflator of public construction investment rose by 19.4% between 2017 and 2021, much faster than the GDP deflator (+9.3%). The price hikes in the construction sector were driven by capacity constraints, as capacity has risen only slowly since the construction sector’s ten-year crisis after the reunification boom came to an end in 2005. At the same time there is an acute lack of staff in public sector planning departments, particularly at the local level, where insufficient funds had caused more than a decade of net negative local-government investment. Moreover, local authorities with the highest needs have tended to face the tightest fiscal constraints on their investment.

Now, even where sufficient funds are being made available, it remains difficult to increase public investment in the short run, as the existing bottlenecks cannot be removed overnight. Both the construction industry and local authorities need a long-term perspective to invest in additional capacities. Recently, public investment has tended to be procyclical, increasing with rising revenues in good times. A more sensible approach would be to stabilise public investment at a high level, providing reliable and adequate funding over the long term.

In the current fiscal framework such a stable long-term perspective is difficult to implement and becomes particularly challenging when the government rules out both tax increases and additional deficit spending. Then the only remaining option for the federal government is to use whatever room for manoeuvre can be created by making use of loopholes in the debt brake―mostly through off-budget operations or procedural changes such as a reform of the cyclical adjustment method. At least the use of the EKF/KTF and public institutions like the state railway company or BImA has the advantage of favouring investment spending. However, this approach makes public investment much less transparent and results in higher financing costs compared to investment via the core budget. Further, it is currently unknown to what extent fiscal space can be increased and it is vulnerable to legal challenges.

It is time for Germany to implement a more investment-friendly fiscal framework. As public investment increases the public capital stock and facilitates economic growth that future generations can benefit from, there is a strong case for a “golden rule” of investment allowing public investment to be credit-financed. This is all the truer for investment in climate protection and renewable energy, which, in addition to its ecological benefits, is also vital for Germany’s future competitiveness. The German government should use the opportunity of the current review of the European fiscal rules to support the introduction of a golden rule, alongside other reforms (Dullien et al. 2020), and adjust the German debt brake accordingly as well as making it more compatible with the European rules.

In the current high-inflation environment additional price pressures should be avoided. Investment affects both the supply and the demand side of the economy. It increases the capital stock and thus strengthens capacity, but in the short run it also increases demand. In theory, a cyclical golden rule that allows higher deficit-financed investment in bad times would be a good idea. However, well-known problems with cyclical adjustment methods may make the practical implementation difficult (Truger 2015). To avoid excessive debt and risks associated with creating excess demand, part of the additional investment spending could be financed by an income tax surcharge or temporary wealth levy. The combination of a golden rule and additional tax revenues would enable a long-term stabilisation of public investment in Germany.

References

Bardt, H., S. Dullien, M. Hüther, and K. Rietzler (2019) For a sound fiscal policy: Enabling public investment! IMK Report No. 152e, https://www.imk-boeckler.de/de/faust-detail.htm?sync_id=HBS-007619.

Beznoska, M. and B. Kauder (2020) Schieflagen der kommunalen Finanzen: Ursachen und Lösungsansätze. Institut der Deutschen Wirtschaft, IW-Policy Paper 15, https://www.iwkoeln.de/studien/martin-beznoska-bjoern-kauder-schieflagen-der-kommunalen-finanzen.html.

Bremer, B., D. di Carlo, and L. Wansleben (2021) The Constrained Politics of Local Public Investments under Cooperative Federalism. Max-Planck-Institut für Gesellschaftsforschung, MPIfG Discussion Paper No. 21/4, https://pure.mpg.de/rest/items/item_3327622_1/component/file_3327623/content.

BMWi (Bundesministerium für Wirtschaft und Energie, Ministry of Economy and Energy) (2018) Energieeffizienz in Kommunen. Energetisch modernisieren und Kosten sparen: Wir fördern das. BMWi, Berlin, https://www.foerderdatenbank.de/FDB/Content/DE/Download/Publikation/Energie/energieeffizienz-in-kommunen-broschuere.pdf?__blob=publicationFile&v=2.

Dullien, S., C. Paetz, A. Watt, and S. Watzka (2020) Proposals for a Reform of the EU’s Fiscal Rules and Economic Governance. IMK Report No. 159e, Düsseldorf, https://www.imk-boeckler.de/de/faust-detail.htm?sync_id=HBS-007716.

Dullien, S., A. Herzog-Stein, K. Rietzler, S. Tober, and A. Watt (2022a) Transformative Weichenstellungen. IMK Report No. 173, Düsseldorf, https://www.imk-boeckler.de/de/faust-detail.htm?sync_id=HBS-008218.

Dullien, S., K. Rietzler, and S. Tober (2022b) Die Entlastungspakete der Bundesregierung. Sozial weitgehend ausgewogen, aber verbesserungsfähig. IMK Policy Brief No. 120, Düsseldorf, April, https://www.imk-boeckler.de/de/faust-detail.htm?sync_id=HBS-008296.

Dullien, S., A. Herzog-Stein, P. Hohlfeld, K. Rietzler, S. Stephan, S. Tober, T. Theobald, and S. Watzka (2022c) Energiepreisschocks treiben Deutschland in die Rezession. Prognose der wirtschaftlichen Entwicklung 2022/2023. IMK Report No. 177, September, https://www.imk-boeckler.de/de/faust-detail.htm?sync_id=HBS-008421.

Dullien, S., E. Jürgens, and S. Watzka (2020) “Public Investment in Germany. The Need for a Big Push”, in F. Cerniglia and F. Saraceno (eds), A European Public Investment Outlook. Cambridge: Open Book Publishers, pp. 49–62, https://doi.org/10.11647/obp.0222.

ExpertInnen-Kommission Gas und Wärme (2022): Sicher durch den Winter. Abschlussbericht. Berlin 31 October 2022.

Federal Ministry of Defence (2022) Kabinett einigt sich auf mehr Geld und Sondervermögen für die Bundeswehr, 16 March 2022, https://www.bmvg.de/de/aktuelles/deutlich-aufgestockt-verteidigungshaushalt-5372564.

Federal Ministry of Finance (2022) German Stability Programme 2022. 2022 Update (and updated German Draft Budgetary Plan 2022), Berlin, https://www.bundesregierung.de/breg-de/suche/german-stability-programme-2022-2028432#:~:text=On%2027%20April%202022%2C%20the,government%20will%20ensure%20fiscal%20soundness.

Krebs, T. and J. Steitz (2021) „Öffentliche Finanzbedarfe für Klimainvestitionen im Zeitraum 2021–2030“, Forum for a New Economy, Working Paper No. 03/2021, https://newforum.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/FNE-WP03-2021.pdf.

Raffer, C. and H. Scheller (2022) KfW-Kommunalpanel 2022, Kreditanstalt für Wiederaufbau, Frankfurt am Main, https://www.kfw.de/PDF/Download-Center/Konzernthemen/Research/PDF-Dokumente-KfW-Kommunalpanel/KfW-Kommunalpanel-2022.pdf.

Rietzler, K. (2022a) “Kommunen zentral für Jahrzehnt der Zukunftsinvestitionen. Beitrag zum Zeitgespräch: Haushaltspolitik der neuen Bundesregierung“, Wirtschaftsdienst, Jg. 102, H. 1., 27–30, https://www.wirtschaftsdienst.eu/inhalt/jahr/2022/heft/1/beitrag/kommunen-zentral-fuer-jahrzehnt-der-zukunftsinvestitionen.html.

Rietzler, K. (2022b) Vorübergehende Energiesteuersenkung klima- und verteilungspolitisch fragwürdig. Ausweitung pauschaler Zahlungen oder Gaspreisdeckel sinnvoller. Written statement for the parliamentary hearing on the temporary decrease of the energy tax on May 16, 2022. IMK Policy Brief No. 122, Düsseldorf, May, https://www.imk-boeckler.de/de/faust-detail.htm?sync_id=HBS-008321.

Rietzler, K. and A. Watt (2021) “Public Investment in Germany: Much More Needs to Be Done“, in F. Cerniglia, F. Saraceno, and A. Watt (eds), The Great Reset: 2021 European Public Investment Outlook. Cambridge: Open Book Publishers, pp. 47–62, https://doi.org/10.11647/obp.0222.02.

Scheller, H., K. Rietzler, C. Raffer, and C. Kühl (2021) Baustelle zukunftsfähige Infrastruktur. Ansätze zum Abbau nichtmonetärer Investitionshemmnisse bei öffentlichen Infrastrukturvorhaben, WISO-Diskurs No. 12/2021, Bonn/Berlin, https://library.fes.de/pdf-files/wiso/17978.pdf.

SPD, Bündnis90/Die Grünen, FDP (2021) Mehr Fortschritt wagen. Bündnis für Freiheit, Gerechtigkeit und Nachhaltigkeit, Koalitionsvertrag 2021–2025 zwischen der Sozialdemokratischen Partei Deutschlands (SPD), BÜNDNIS 90 / DIE GRÜNEN und den Freien Demokraten (FDP), https://www.spd.de/fileadmin/Dokumente/Koalitionsvertrag/Koalitionsvertrag_2021-2025.pdf.

Wissenschaftlicher Beirat beim Bundesministerium für Wirtschaft und Energie (2020) Öffentliche Infrastruktur in Deutschland: Probleme und Reformbedarf, Berlin, https://www.bmwk.de/Redaktion/DE/Publikationen/Ministerium/Veroeffentlichung-Wissenschaftlicher-Beirat/gutachten-oeffentliche-infrastruktur-in-deutschland.html.

1 For comparability between states it is important to aggregate the state and local levels as the division of responsibilities between state and local levels differs between the German states. (State abbreviations: BW = Baden-Württemberg, BY = Bavaria, BE= Berlin, BB = Brandenburg, HB = Bremen, HE = Hesse, HH = Hamburg, MV = Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, NI = Lower Saxony, NW = North Rhine-Westphalia, RP = Rhineland-Palatinate, SL = Saarland, SN = Saxony, ST = Saxony-Anhalt, SH = Schleswig-Holstein, TH = Thuringia).

2 Personal communication from EU Commission country desk.