7. Europe’s Green Investment Requirements and the Role of Next Generation EU

© 2022 Chapter Authors, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0328.07

Introduction

Policymakers have made a clear commitment to use the European Union’s post-pandemic recovery plan, Next Generation EU, to accelerate the bloc’s green transition. The underlying idea is simple: seize a moment of unprecedented economic and social disruption to reinforce the reorientation of Europe’s economic model towards sustainability, and in particular to accelerate the implementation of the European Green Deal.

This idea also reflects a hope that green investments will have high fiscal multiplier effects and that they can achieve in one swoop a so-called ‘triple dividend’ promoting economic growth, fostering job creation and reducing greenhouse gas emissions (Hepburn et al. 2020). While this might be overly optimistic, it has shaped policymakers’ preference and means that significant parts of the EU’s recovery fund will be spent on green investments.

In practice, this has meant setting a 37% minimum target for spending on climate objectives under the Recovery and Resilience Facility (RRF), the largest component of Next Generation EU.

For this it is, of course, necessary to define ‘green’, ‘climate’ and ‘environmental’ spending. The regulation establishing the RRF (Art. 18) includes three different requirements that must be met by EU countries’ recovery and resilience plans, which are the framework for RRF spending:

- All proposed measures must respect the ‘do no significant harm’ principle in relation to environmental objectives, and adherence to this must be demonstrated;

- Countries must explain how their plans contribute to ‘the green transition’. This term refers to both environmental and climate-change objectives and is not subject to a target;

- At least 37% of a plan’s spending must go to measures which are specifically meant to support climate-change objectives, a narrower aim than the ‘green transition’. The regulation provides coefficients to be used for the calculation of each measure’s contribution to the target. Note that there are also coefficients for ‘environmental objectives’, but no minimum share of spending was established for these.

Bruegel’s dataset of EU countries’ recovery and resilience plans, and the European Commission’s assessments (2021), show that all countries have met this 37% minimum requirement. However, in some cases the Commission’s assessment of the plans reported a different ‘climate share’ than originally stated by the member states concerned (e.g. higher for Austria while lower for France and Italy). The Commission judged that all plans respected the ‘do no significant harm’ principle to a great extent.

In this chapter, we look at both the climate and environmental components of the national plans in the RRF framework to understand countries’ spending priorities in these fields. Including both of these areas in our analysis is important, as doing so better reflects the encompassing nature of the European Green Deal.

7.1 Overall Priorities

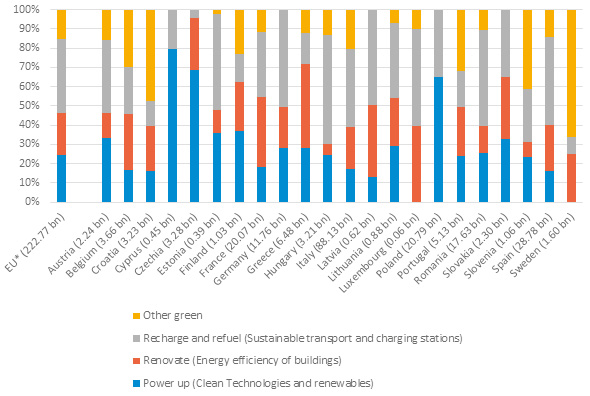

We first looked at each country’s green spending, as categorised under the European Commission’s green ‘flagship areas’: Power up, Renovate and Recharge and Refuel (referring, broadly, to cleantech, building energy efficiency and sustainable transport). This provides an understanding of overall spending priorities. Note that the numbers we present here are different from the allocations to climate-change objectives, as reported in the national plans and Commission assessments, since we count the full allocations of measures included in the relevant categories (though some of their components might not contribute to climate objectives) and exclude some measures that contribute to the 37% target but have a non-green primary focus.

When classified this way, national allocations differ significantly (Figure 7.1). For the EU as a whole, Recharge and Refuel is the main green spending priority, accounting for more than a third, or €86 billion. For countries including Estonia, Germany, Hungary, Latvia, Luxembourg and Romania, this area even accounts for 50% or more of all green spending. Italy and Spain also have notably high sustainable transport allocations.

The Power up priority has been allocated around a quarter of green spending at the EU level, or €55 billion. Shares are, however, much larger in countries including Cyprus, Czechia and Poland, which allocate close to two thirds or more to this area. Though not visible in Figure 7.1, Sweden also spends money on this, but the amount could not be singled out based on the information in the plan, and therefore falls within the ‘other green’ category. Some spending on renewable energy is included under Renovate for Luxembourg.

The smallest green flagship in spending terms is Renovate (energy efficiency of buildings), which receives €48 billion in the EU. France, Greece, Latvia, Slovakia and Belgium go against the trend by devoting considerably higher shares to improving their building stocks.

Finally, ‘other green’ in Figure 7.1 captures spending that either could not be put into one single category, or which is primarily devoted to other items in support of the green transition. This amounts to €34 billion of spending on measures including reforestation and biodiversity protection. For Sweden it includes broad ‘climate investments’ with many different elements. Luxembourg directs half of its green spending to environmental protection and biodiversity, and Croatia plans relatively high spending on waste and water management and tourism. Finally, a significant share of Slovenia’s ‘other green’ goes to water management and flood prevention.

Fig. 7.1 Green spending in the national Recovery and Resilience Plans, counted using the European Commission’s flagship classification (% of total green spending).

Source: Bruegel based on submitted national recovery plans. Note: country names are followed by total green spending in € in brackets. These amounts are the sums of spending (grants and loans) categorised under the flagships Power up, Renovate, Recharge and Refuel, and a residual category, ‘other green’. Some measures that also contribute to the green transition but are aimed primarily at other fields are not included. Total green spending can therefore differ from the total amounts of spending related to climate change objectives as reported by the plans, which are calculated with weights assigned to individual spending items by member states and which should be at least 37% of total RRF spending within a country.* Includes twenty-two countries currently in the dataset.

7.2 A More Detailed Examination

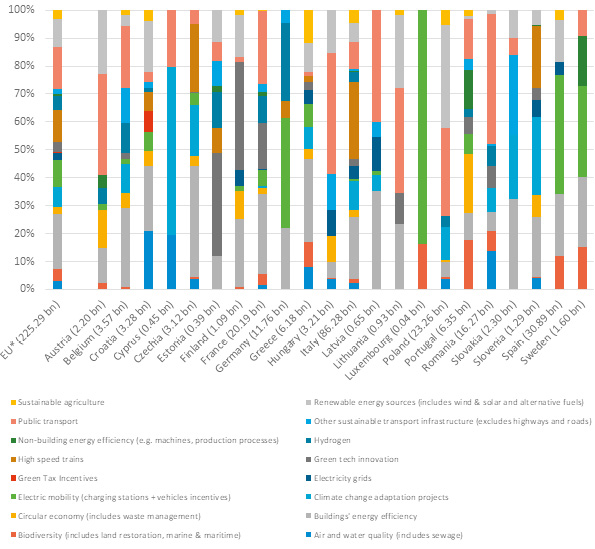

While the Commission’s flagship-based classification is useful for getting an overall idea of green spending priorities, a more granular breakdown is required to understand thoroughly the measures countries intend to put in place (Figure 7.2). Bruegel introduced its own classification to allow for this sort of deeper analysis.

Unsurprisingly, this more detailed classification also reveals significantly varying national spending priorities. In EU aggregate terms, spending to increase the energy efficiency of buildings takes the largest share, with €45 billion, almost a fifth of total green spending. This usually concerns both public and private buildings, sometimes explicitly targeting social housing as part of a ‘just transition’ narrative. Belgium and France have made renovations the largest component of their green spending, devoting around 28% to it. Czechia, Greece, Latvia and Slovakia spend even larger shares on this, reflecting what is shown in Figure 7.1.

The second biggest category at the EU level is public transport, with €34 billion, or 15%. This is a particularly large part of planned green spending in Romania (47%) and also in Austria, Hungary, Latvia and Lithuania, where it accounts for more than a third of green spending.

We created a separate category for high-speed trains, which ranks third in size with €26 billion, or 12%. Almost all the planned investments are in Italy (€24 billion), where it is one of the largest spending categories. The rest of the spending on high-speed trains is planned most notably in Czechia and Germany. Taken together, spending on ‘regular’ public transport and on high-speed trains surpasses spending on renovations in the EU as the biggest green subcomponent.

The fourth biggest category in the EU is renewable energy sources, which receives €23 billion, or around 10% of green spending. Most of this spending will be concentrated in three countries: it is the biggest green component for Poland with 37% (€9 billion); Spain and Italy will also be big spenders in absolute terms, with €5 billion and €6 billion respectively. Remarkably, renewables don’t really feature in the French and German plans, which allocate substantial amounts to hydrogen development instead.

Finally, measures specifically targeting hydrogen come in seventh place at the EU level, behind electric mobility (mostly championed by Germany and Spain) and climate adaptation. Countries will spend in total €11 billion (5% of green spending) on this alternative fuel, with €3 billion of spending planned in Germany, €3 billion in Italy, €2 billion in France, and around €1 billion each in Poland and Romania.

Fig. 7.2: Green spending by Bruegel’s own Level 2 classification (% of total green spending).

Source: Bruegel based on submitted national recovery plans. Note: the classification used is ‘Bruegel Level 2, 1st’ from the Bruegel dataset. Country names are followed by total green spending (as defined by Bruegel’s Level 1 classification) in € in brackets. Some measures that also contribute to the green transition but are primarily aimed at other fields are not included. Total green spending can therefore differ from the total amounts of spending related to climate change objectives as reported by the plans, which are calculated with weights assigned to individual spending items by member states and which should be at least 37% of total RRF spending within a country.* Includes twenty-two countries.

Depending on which classification system is used, at the EU level some €225 billion of the RRF funds is set to be spent on green elements. This is certainly a welcome and necessary effort, but it pales in comparison to the annual investment needed by 2030 to realise the aspirations of the European Green Deal, as illustrated hereafter.

Investment Requirements to Deliver the European Green Deal and Global Net-zero Pledges

To become climate neutral by mid-century, the European Union and other major economies must substantially reduce their greenhouse gas emissions during this decade. The EU aims to reduce its emissions by 55% by 2030 compared to 1990 levels with a wide range of policies proposed in the European Commission’s ‘Fit for 55’ package. Meanwhile, the United States aims to reduce its emissions by 50–52% by 2030 compared to 2005 levels,1 and China wants its CO2 emissions to peak before 2030. To achieve this, major investment will be needed.

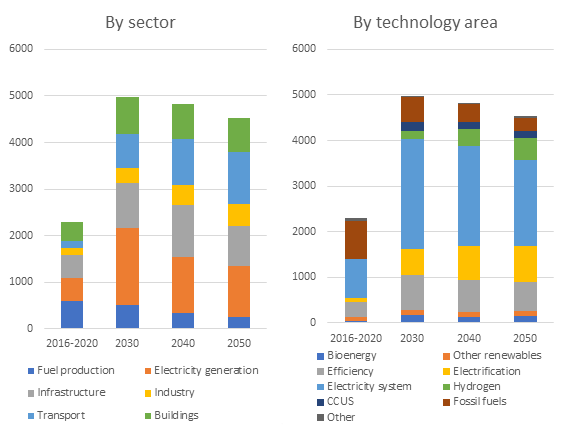

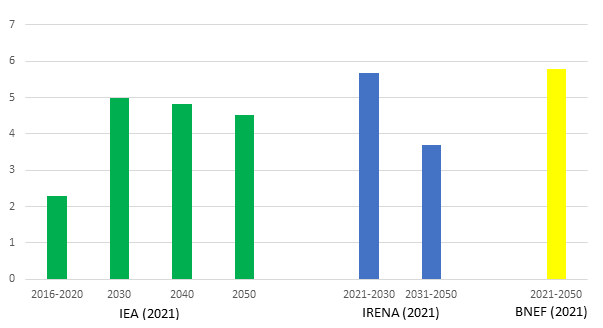

To understand the investment required to deliver on these pledges it is useful to review the multiple estimates in the field. Global energy investment currently stands at around $2 trillion per year or 2.5% of global GDP, according to the International Energy Agency (IEA). In an illustrative pathway (IEA 2021), this will have to rise to $5 trillion or 4.5% of GDP by 2030 and stay there until at least 2050 to reach net zero CO2 emissions by 2050 (Figure 7.3). Much of this will be spent on electricity generation and infrastructure to electrify new economic sectors and to make the electricity system more suitable for much higher volumes and variability of renewable energy.

Fig. 7.3 Annual average capital investments worldwide to reach net-zero CO2 emissions by 2050 ($ billions, 2019 prices).

Source: International Energy Agency (2021).

Other net-zero pathways point to similar orders of magnitude (Figure 7.4). The International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA 2021) frontloaded the necessary investments into the 2020s, resulting in global investments of $5.7 trillion per year until 2030, though these decrease to less thereafter. Bloomberg New Energy Finance (BNEF 2021) estimated the average investment requirements to be between $3.1 trillion and $5.8 trillion per year up to 2050.

Fig. 7.4 Average yearly global investment needs in order to reach net-zero CO2 emissions from energy by 2050, different estimates ($ trillions).

Source: Bruegel.

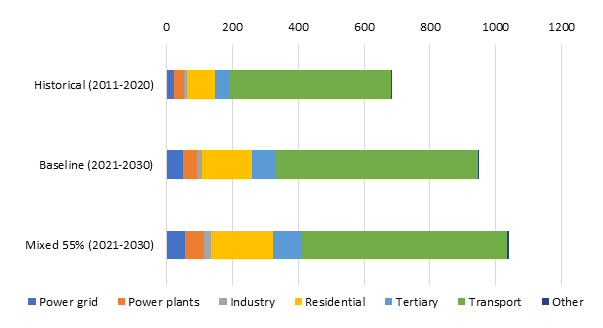

For the EU, the European Commission (2020) estimated that reaching the 2030 climate target will require additional annual investments of €360 billion on average, starting now. This will raise relevant investments from an average of €683 billion per year in the last decade to around €1,040 billion per year. Roughly a third of the additional investment is in transport, by far the largest component because of substantial vehicle replacement needs. Apart from transport, the emphasis seems to lie more on doubling investment in residential heating, but smaller components, such as power grids and plants, still have to increase by a factor of two (Figure 7.5).

Fig. 7.5 Average annual investment needs to reduce EU emissions by 55% by 2030, compared to baseline trend and historical data (€ billions, 2015 prices).

Source: European Commission (2020). Note: ‘Mixed 55%’ is a scenario (MIX) that features a combination of expanded carbon pricing and moderately increased ambitions in energy regulations. The baseline is a scenario in which current policies and targets for 2030 continue to apply (-40% emissions).

According to all of these estimates, reaching climate neutrality by 2050 will thus require investments in energy and transport systems roughly 2 percentage points of GDP higher than current levels. No government can finance this with public money alone, so enabling and incentivising policies such as carbon taxes and green financial regulation will be necessary to mobilise private investments. Governments could also try to focus their spending on areas and initiatives from which viable companies can arise, as part of a green industrial policy (Tagliapietra and Veugelers 2020). The extent to which governments can rely on private funding for these additional investments will vary widely between countries (see, for example, EIB 2021 for EU countries), but given the large overall expansion, global public energy investments may need to double in absolute terms even with significant private participation (IRENA 2021). In the EU, a rough estimate suggests additional public investments of €100 billion per year are required (Darvas and Wolff 2021).

7.3 Conclusion

The green spending financed by the Recovery and Resilience Facility may serve primarily as a short- to medium-term stimulus policy. In reality it will have to be the start of a bigger and sustained investment push to make the European economy climate-neutral and able to prosper in a post-fossil fuel world. The national recovery plans suggest that member states have different needs and approaches, and make choices between, for example, renewables versus nuclear energy or electric cars versus public transport and high-speed trains. All countries have in common however that massive mobilisation of private funding will be necessary, given the limited fiscal space of most governments. Spending choices need to create opportunities for private initiatives to take off, and suitable policies and regulation must incentivise and facilitate.

References

BloombergNEF (2021) New Energy Outlook 2021, BloombergNEF, https://about.bnef.com/new-energy-outlook/.

Darvas, Z. and G. Wolff (2021) “A Green Fiscal Pact: Climate Investment in Times of Budget Consolidation”, Policy Contribution 18/2021, Bruegel.

European Commission (2020) “Impact Assessment Accompanying the Document ‘Stepping up Europe’s 2030 Climate Ambition. Investing in a Climate-neutral Future for the Benefit of Our People’”, SWD/2020/176 final, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A52020SC0176.

European Commission (2021) “Recovery and Resilience Facility”, https://ec.europa.eu/info/business-economy-euro/recovery-coronavirus/recovery-and-resilience-facility_en#national-recovery-and-resilience-plans.

European Investment Bank (2021) EIB Investment Report 2020/2021: Building a Smart and Green Europe in the COVID-19 Era, https://www.eib.org/en/publications/investment-report-2020.

Hepburn, C., B. O’Callaghan, N. Stern, J. Stiglitz and D. Zenghelis (2020) “Will COVID-19 Fiscal Recovery Packages Accelerate or Retard Progress on Climate Change?”, Oxford Review of Economic Policy 36 (1), 2020: S359–S381, https://academic.oup.com/oxrep/article/36/Supplement_1/S359/5832003.

IEA (2021) Net Zero by 2050 A Roadmap for the Global Energy Sector. Paris: International Energy Agency, https://www.iea.org/reports/net-zero-by-2050.

IRENA (2021) World Energy Transitions Outlook: 1.5°C Pathway. International Renewable Energy Agency, https://www.irena.org/publications/2021/Jun/World-Energy-TransitionsOutlook.

Tagliapietra, S. and R. Veugelers (2020) A Green Industrial Policy for Europe, Blueprint 31, Bruegel, https://www.bruegel.org/2020/12/a-green-industrial-policy-for-europe/.