8. The Public Spending Needs of Reaching the EU’s Climate Targets

© 2022 Claudio Baccianti, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0328.08

Introduction

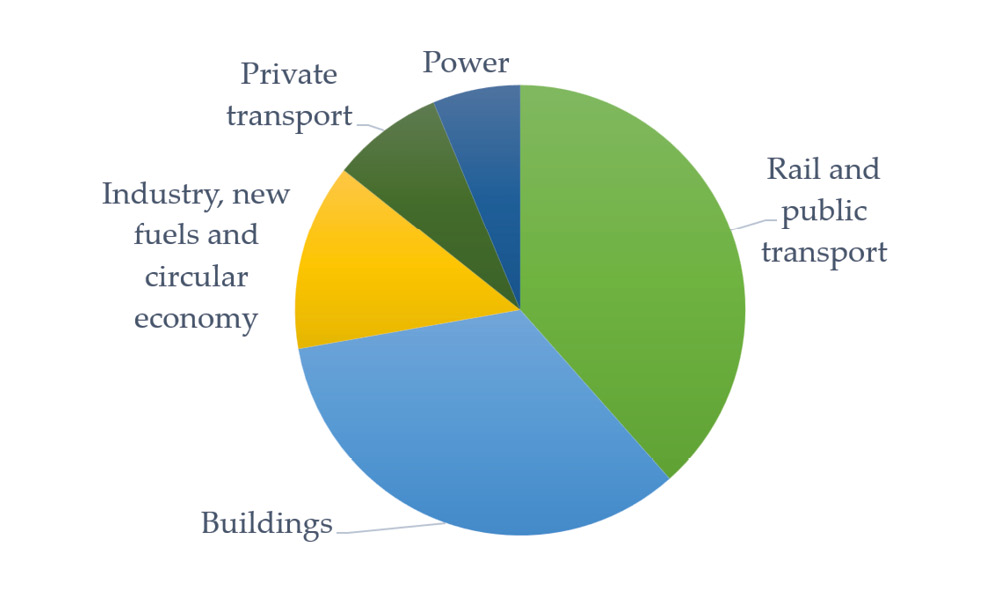

The European Green Deal has set the clear goal of reaching net-zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050, bringing climate action centre stage. The revised intermediate 2030 target of reducing greenhouse gas emissions by at least 55% compared to 1990 levels has triggered a comprehensive revision of relevant EU and national legislations and funding schemes. Since then, it has become even more evident that the green transition will have important economic and fiscal effects across the EU even before 2030. While the investment needs of EU climate policy are often discussed, understanding of the fiscal implications is still limited. This article offers an estimate of the climate public spending needs in the EU, based on a review of the evidence and literature for each sector. In the current decade, public expenditures on green investment should increase by 1.8% of GDP in a scenario with a balanced policy mix. Most of the spending will go to the buildings and transport sectors (Fig. 8.1).

The fiscal costs of the green transition can be minimised by making extensive use of carbon pricing, regulation (emission standards), soft loans and de-risking instruments. The regulator can trigger emission abatement by making low-carbon technologies cheaper (e.g. tax incentives) or traditional fossil-based and inefficient alternatives more expensive (carbon pricing), or a mixture of both. Because of political economy considerations, politicians prefer to offer generous financial support to green investment, shifting the burden to public finances.

Even if governments will successfully crowd in as much private capital as possible, the public share of the aggregate investment costs should still be close to 50%. Public budgets are one of the main sources of funding for key infrastructures in the power and transport sectors. Moreover, a large stock of buildings to be renovated is publicly owned, and low-income households will need substantial public support to renovate their homes. During this decade there is also the need to deploy technologies like green hydrogen and low-carbon industrial solutions that are still expensive and will rely on public funding for a while.

Fig. 8.1 Composition of public spending to support green investment in 2021–2030 in the EU.

Source: author’s calculation.

8.1 A Sectoral View of the Public Spending Needs in the EU

8.1.1 Power Sector

8.1.1.1 Power Generation

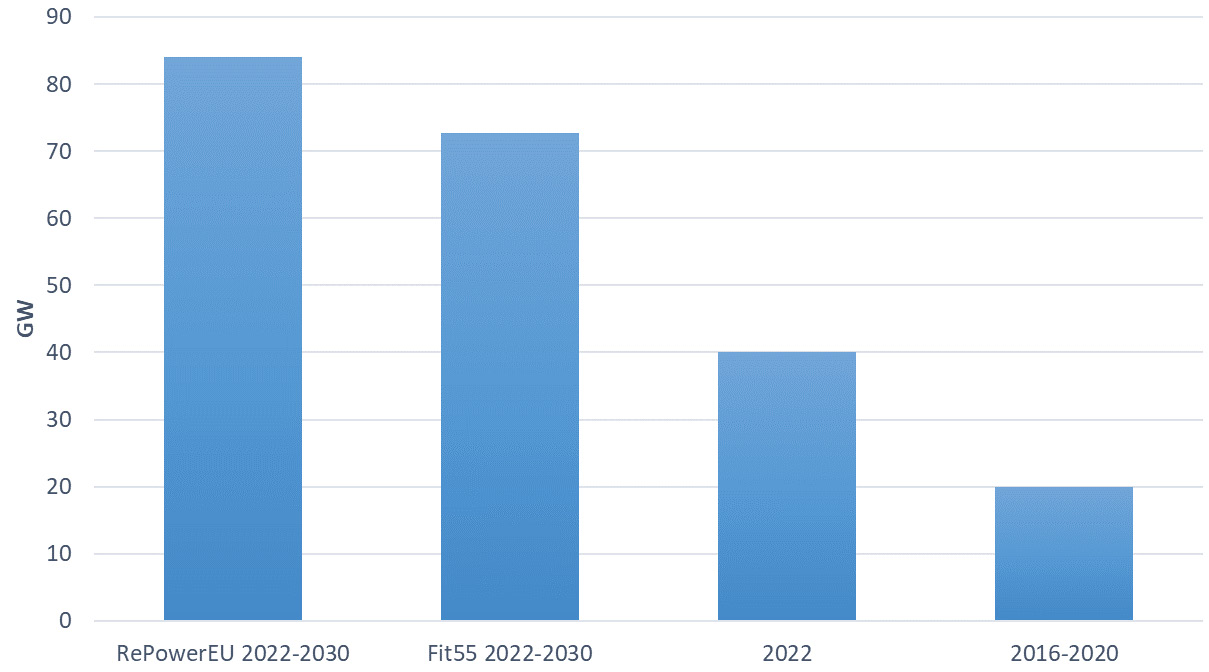

The rapid deployment of renewable power generation is essential to displace fossil-based power plants and to feed the growing electricity demand from green hydrogen production and the diffusion of heat pumps and electric vehicles. According to the European Commission, the total renewable energy generation capacity in the EU should reach 1236 GW by 2030, of which 510 GW of wind and 592 GW of solar PV, under the RePowerEU plan. The rate of deployment must increase very quickly (Fig. 8.2 Solar and wind power—Annual change in installed capacity in the EU.). Only 20 GW per year of solar and wind power capacity were added in 2016–2020,1 and around 40 GW will be installed in 2022, according to the IEA (2022). To reach the 2030 RePowerEU targets, annual capacity additions for renewable power will have to stay close to 85 GW through this decade.

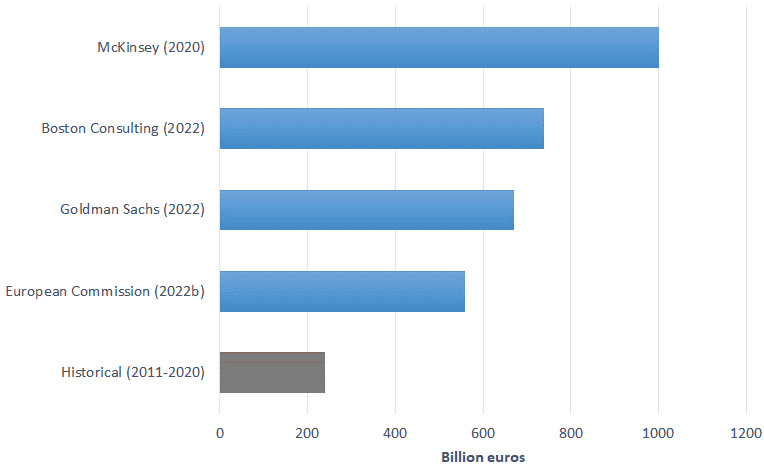

However, tripling or quadrupling the annual renewable capacity additions may still lead to investment flows no higher than what Europe experienced in the 2010–2011 boom. In those years, the EU annual investment in renewable power generation reached 80 billion euros, and then rapidly dropped and hovered around 30 billion in 2013–2019.2 In the meantime, the investment costs per GW installed for solar and wind power have declined sharply between 2010 and 2020, i.e. 81% for solar PV and 31% for wind globally (IRENA 2021). To reach the 2030 EU climate targets, available studies estimating the power generation investment needed in 2021–2030 put annual capital expenditures between 45 and 80 billion euros per year (Baccianti and Odendahl 2022). However, these figures do not account for the revised ambitions of the RePowerEU plan and the current reversal of the long-term renewable investment cost decline, which followed the COVID-19 crisis. As prices of key commodities such as steel, copper and aluminium skyrocketed, the costs of solar PV modules and wind turbines also increased and are expected to remain higher than the pre-pandemic levels until 2023, while remaining competitive with fossil fuels (IEA 2022).

Fig. 8.2 Solar and wind power—Annual change in installed capacity in the EU.

Sources: Author’s calculations on European Commission (2022b), IEA (2022), Eurostat data.

New solar and wind power generation projects are much less dependent on public support than in the past, and the private sector is expected to provide a high share of the financing needs. The OBR (2021) and IEA (2021) expect the direct contribution of public funding to renewable power investment to be below 20% in net-zero by 2050 scenarios. Globally, in 2013–2018 the public sector share of total investment financing was 14% on average (around 30% for off-grid renewables). Grants and subsidised loans made only 4% of capital expenditures, with shares up to 10% in Europe (IRENA and CPI 2020). However, IRENA and CPI (2018) point out that, while the share of capex support in Western Europe was 20% in 2015, the public sector contribution to investment costs reached 55% when revenue support (e.g. feed-in tariffs, etc.) is included. Since then, support schemes have been reformed across Europe, shifting to a larger reliance on market-based revenues. Thanks to fast-declining production costs for renewable power, reforms reduced the subsidy rate for new installations. The average subsidy to supported plants dropped from 110.22 €/MWh in 2015 to 97.95 €/MWh in 2019, with solar PV plants still receiving more than 200 €/MWh on average in several countries in 2019 (CEER 2021).3

Going forward, so much new solar and wind power capacity is needed that part of the new plants will have to be located in less productive locations. Small scale rooftop solar PV, agri-voltaics and off-shore wind power will play an important role to reduce land consumption and their potential is high. Rooftop solar PV in the EU could produce 680 TWh of solar electricity annually, which is equal to around one quarter of the current EU power demand (Bodis et al. 2019). Using just 4% of the arable land in Germany for agrivoltaics—that is the dual use of agricultural land to produce farming products and solar power—could satisfy the entire German power consumption (Trommsdorff et al. 2020). However, these solutions have a higher levelised cost of electricity generation and will demand more direct subsidies than utility-scale solar or onshore wind. Generating electricity on arable farming land and rooftops can be on average twice as expensive over a twenty-year period as using ground-mounted solar PV plants, while the cost disadvantage is less pronounced for agrivoltaics on permanent crops and grassland (Trommsdorff et al. 2020). Agrivoltaics is a new and relatively niche market at the moment, with strong potential for cost-cutting innovation.

The impact that the support of new renewable power generation will have on public finances will depend on the policy design and on market conditions. In twenty-one out of twenty-eight member states, renewable support schemes have been financed via special levies and not general taxation over the last few years (CEER 2021). Charging a levy on the final electricity price relieves the government budget from the cost of supporting renewables, while allowing the possibility to intervene and temporarily ease the burden on consumers. In 2022, Germany joined the group of countries financing the renewables support scheme via the state budget. Furthermore, the policy cost will depend on the dynamics of wholesale power prices and capture, carbon and gas prices, as well as the level of demand over the next two to three decades (Agora Energiewende 2022)

8.1.1.2 Power Grids

Investment in power grids is necessary to enable the electrification of energy demand and the penetration of intermittent renewable power generation. Transmission lines will have to be strengthened to allow renewable power generated in high-performing areas to reach other regions, and to accommodate for higher electricity consumption. The digitalisation and upgrade of distribution networks and adoption of storage technologies will balance the market in the presence of a high share of renewables in power generation.

The investment gap estimates significantly vary across studies, especially regarding the additional needs before 2030 (Fig. 8.3 Cumulative investment in power grids in 2022–2030 and historical.), while all much higher than historical levels. These differences can be explained by disparate views on the rate of electrification. From these and other studies we learn that investment flows into distribution networks will be larger than those into transmission lines (IEA 2021; Goldman Sachs 2022), and that investment should scale up after 2030, as power demand and the share of renewable generation are substantially higher.

The ownership of transmission and distribution system operators varies across EU countries. Power infrastructure companies are all or mostly publicly owned in France, Sweden, the Netherlands and Latvia, while in Spain, Portugal and Italy the ownership is mainly private. Other countries have mixed models (CEER 2022). Governments can in part contribute through grants and direct investment, as for instance with 8.5 billion euros of dedicated investments in different national recovery and resilience plans (European Commission 2022a). But in general, power grid investment is financed through corporate debt and consumer levies, i.e. network charges, and not general taxation. However, as electricity tariffs are regulated, grid operators may experience budget deficits that eventually require governments to step in. In the past, this kind of contingent liability posed a limited risk to public finances even in the most exposed countries (Linden et al. 2014), but the situation should be reassessed in light of the large investment needs.

Fig. 8.3 Cumulative investment in power grids in 2022–2030 and historical.

Note: historical investment from European Commission (2021a).

8.1.2 Buildings and District Heating

The decarbonisation of buildings, in particular private and residential, is one of the top challenges in the transition to net-zero emissions. Markets for energy-saving building retrofits across the EU will need to undergo an unprecedented transformation, doubling or tripling the annual rate of renovation of the building stock and shifting towards deep renovations. According to the European Commission, thirty-five million buildings should be retrofitted by 2030 to meet the climate targets and the electrification of heating systems should speed up significantly—soon reaching a 4% annual replacement rate of fossil fuel boilers.

Buildings account for 69% of the non-transport climate investment gap in 2021–2030, according to the Commission’s modelling (European Commission 2020b). Both the European Commission (2020b) and McKinsey (2020) estimate that energy-related investments in the building sector should reach 300 billion euros per year between 2021–2030. This figure is 160 billion euros higher than investments in the sector over the last decade, so capital expenditures should more than double rapidly from those levels. A recent study by the Joint Research Centre (Wouter et al. 2021) stated that the renovation of the building envelope and space heating of existing residential buildings alone (excluding new and non-residential constructions) would require 91 billion euros more in annual investment in 2021–2030. Reducing the cost of energy-saving renovation is complicated by a lack of standardisation and serial renovations (BPIE 2020). The heterogeneity of the building stock forces architects and construction companies to adopt customised solutions, a condition that weighs on costs.

The number of homes undergoing energy-saving renovations every year has historically been too low to make a dent in emissions. While spending in home renovations stands at around half a trillion euros annually, most of the spending—60%—is for interventions that do not affect the energy efficiency of the building (European Commission 2019). While 12% of the EU housing stock every year actually undergoes some kind of energy-saving renovations, only one out of ten of those retrofits achieves substantial primary energy savings above 30%. To achieve the EU’s 2030 climate targets, the current annual rate of energy renovations will have to double by 2030 and the share of ‘deep’ renovations, delivering primary energy savings of at least 60%, should rise from 0.2% of dwellings each year to 1.3–1.7% in 2030 (European Commission 2020b).

Private finance will continue to play a key role in financing building renovations, but governments must step up support if they want to increase the rate of retrofitting quickly. The development of instruments such as green mortgages and on-bill financing can unlock the full potential of private capital. However, there are several reasons why public grants and tax incentives will have to cover a significant share of capital expenditures, in order for the emission reduction targets to be achieved:

- the climate externalities from consuming energy and emitting greenhouse gases in the residential and commercial sectors are often insufficiently priced (OECD 2021), and public funding has to fill the incentive gap.

- Other social benefits are not fully internalised in the cost of energy efficiency renovations. Carrying out a deep home renovation can significantly reduce the load on the power grid of switching to a heat pump. But it may not always be attractive for households to pay for the high upfront costs of improving the thermal envelope of the building because of the long payback times (Element Energy 2022). Without the energy efficiency investment, a larger heat pump with higher power demand is installed, leading to higher system costs. Public grants and tax incentives can increase the rate of deep renovations, reducing the effect of heat pump deployment on the power grid.

- Subsidies can be an effective instrument in the short term to quickly scale up the deployment of energy efficiency and clean heating technologies, creating markets for these technologies, attracting talent and inducing further innovation in the sector.

Energy renovation policies and the fraction of costs covered by grants and tax incentives widely vary across EU countries. Economidou et al. (2019) estimated that national governments in the EU were spending around 15 billion euros annually in fiscal support schemes during the 2010s. The most generous scheme currently active is the Italian Superbonus 110% (or Ecobonus), which waives the full cost to the homeowner of renovations delivering an upgrade of two energy classes in the national scale, up to predetermined cost thresholds. Other countries, notably Germany, make a more balanced use of grants and low-interest loans. Building renovation programmes were an important component of the post- COVID-19 recovery plans in Europe, especially those projects financed through the Recovery and Resilience Facility. In the twenty-two plans approved in 2021, energy efficiency programmes for residential buildings received 28.4 billion euros, and 20.2 billion euros were allocated to the renovation of public buildings, in both cases to be spent by the end of 2026 (European Commission 2022a).

Millions of residential buildings housing low-income households will have to be renovated by 2030. Individuals at risk of poverty or social exclusion4 alone make up 20.9% of the EU population and, even for households in the broader group of low-income earners, the upfront cost of comprehensive energy renovations is not affordable. Moreover, energy expenditures of the lowest income deciles are in absolute value lower than those of richer households,5 a factor that tends to increase the payback period of home renovations, making them less attractive for low-income households. In countries like the Netherlands, home renovation aid is traditionally provided through social housing, while in Southern and Eastern Europe (and also Germany) subsidised rental housing covers a very small fraction of the housing stock. Governments should create or enhance special programmes to renovate low-income homes. Such policies are becoming increasingly urgent as national and EU regulations mandate the renovation of the most energy-consuming buildings by the beginning of the next decade.

Governments of EU countries with lower incomes may have to provide overall higher grants and subsidies for residential renovations, compared to those of richer EU member states. BPIE (2020) argues that more public funding is needed in Southern, Central and Eastern EU countries to mobilise a given amount of investment in home renovations compared to West and North-West Europe (a leverage factor of 1.5 instead of 3). In fact, in lower-income countries, renovation costs tend to account for a higher percentage of GDP. While labour and installation costs are lower in Bulgaria, Greece, Portugal and Romania than in richer EU countries, the price of insulation materials, heat pumps and solar panels should not be significantly different. With the proposed revision of the ETS, European Commission (2021c) estimates that annual residential capital costs in 2030 will increase more as a share of aggregate household consumption in lower-income EU countries (0.97%) than in high-income ones (0.62%).

Non-residential buildings will have to contribute too, and the quite large share of public ownership increases the fiscal costs of renovating this part of the stock. A quarter of the total building area in the EU is used for commercial and public services.6 Public buildings, i.e. public offices, buildings for public education and health services, make on average around 30% of the non-residential building stock,7 with stark differences across EU countries. Only 10% of non-residential floorspace was publicly owned in Greece in 2011, whereas the public share was close to 90% in Estonia and Bulgaria (Economidou et al. 2011). Even if time series data on the ownership structure of non-residential buildings in the EU are not available, public shares are thought to have fallen over the last three decades as European governments privatised education and health services and sold buildings to finance the reduction of public debt stocks.

Finally, district heating and cooling is another important component in the decarbonisation of the energy consumption in buildings. Centralised and large-scale heat generators can provide energy efficiency gains compared to individual heating and some EU countries have traditionally invested seriously in this solution. In Poland and Slovakia district heating provides around 20% of the energy consumed in residential buildings, while the figure is somewhere between 30% and 40% in Finland, Estonia, Sweden and Denmark. In Southern and Western Europe the contribution of district heating is instead significantly smaller, at below 10%.8

There are therefore sizeable investment needs and opportunities in the district heating and cooling sector across Europe, either to expand the grid and generation infrastructure or to switch existing plants away from fossil fuels. McKinsey (2020) estimates that 500 billion euros are needed up to 2050 to install new district heating networks in the EU, and it considers this technology to have low abatement costs and to be the best replacement for fossil fuel boilers in densely populated areas and hard-to-retrofit buildings. Similarly, Mathiesen et al. (2019) pin down the spending needs in the sector at 865 billion euros over the same period (of which around 60% is in addition to current trends), with most of the investment carried out before 2040.

8.1.2.1 Industry, Hydrogen and Waste

The industry transition to zero emissions requires a comprehensive policy framework that encompasses the different steps of the value chains. Upstream interventions include the expansion of the zero-emissions hydrogen production capacity, i.e. electrolysers, and the investment in hydrogen and CO2 pipelines. The production of intermediate goods can be decarbonised with investment in clean technologies supported by capex and opex support. Moreover, measures like a border carbon adjustment may be needed to preserve firms’ competitiveness in trade-exposed industries. Currently, these industries receive free allowances in the EU ETS, a subsidy scheme that is worth around 43 billion euros per year with a carbon price of 80 euros per ton of CO2eq. Final demand can also steer incentives through the value chains when regulation on embedded CO2 and materials consumption is in place.

Zero-emissions hydrogen will be a key enabler of the industry green transition and it will be used to replace fossil fuels both as fuel and as feedstock in industrial processes. Hydrogen is already used widely, but it is produced with fossil fuels, mostly coal, and must be replaced with green hydrogen. Manufactured with electrolysers and renewable power, green hydrogen is currently more expensive than the “brown” alternatives and it requires a substantial amount of new renewable power capacity. The EU targets the exponential increase of renewable hydrogen production capacity from almost zero today to 40 GW by 2030. RePowerEU plan updated this target to 10 million tons of domestic renewable hydrogen production and 10 million tons of renewable hydrogen imports by 2030. Biomass, biogas and biomethane will also play an important complementary role in decarbonising industry.

The investment needs in industry and hydrogen supply are relatively small compared to other sectors. In a scenario compatible with the Fit for 55 targets and regulation, the European Commission estimates that industrial investment should rise from around 11 billion euros per year in 2011–2020 to 26 billion euros per year in 2021–2030, which is more than double past levels (European Commission 2021a). McKinsey (2020) instead evaluated the green investment gap in the sector at 8 billion euros per year in this decade. These spending needs increased after the war in Ukraine made it urgent to reduce gas consumption. The RePowerEU plan adds 4.5 billion euros per year up to 2030 of investment in industry and around 4 billion euros p.a. in biomethane to eliminate Russian gas imports (European Commission 2022b).

Investment grants for low-carbon industrial projects should absorb the higher capex and cover 20–30% of the investment costs in most cases, with support declining in the technological maturity (Material Economics 2022). Material Economics estimates that scaling up key breakthrough technologies in steel, petrochemicals and cement production in the EU would require 6–11 billion euros in grants up to 2030, to mobilise 31–37 billion euros of green investment. The EU Innovation Fund, which finances innovative low-carbon technologies not only in industry, plays a key role in this area and supports up to 60% of capital expenditures.

The fiscal cost of scaling up green investment in heavy industries will come not only from one-off investment grants but also from recurring subsidy payments. Investments such as energy efficiency improvements and the switch to industrial heat pumps increase productivity and lower the unit costs of production. In other cases, i.e. switching to green hydrogen or capturing and storing emissions, the plant production costs rise. Agora Energiewende (2022a) estimates that decarbonising the production of 11 Mt of steel in Germany before 2030 would increase capital expenditures in the sector by 8 billion euros and operating expenditures by 27 billion euros over ten years (a so called “revenue gap”). While part of these additional production costs may be eliminated in the future with technological progress on the green inputs, i.e. green hydrogen, the rest should be covered either by carbon pricing or public subsidies.

Opex support can take the form of long-term support contracts such as Carbon Contracts for Difference (CCfD). The CCfD commits the public sector to pay a subsidy covering the gap between the actual carbon price and the strike price, for each unit of product manufactured using the green technology. This instrument tracks the realised revenue gaps and reduces the risk of overcompensating investors, contrary to upfront grants. CCfDs have recently gained more and more interest from policymakers. Germany is financing a pilot scheme with 550 million euros under its recovery and resilience plan, and the EU Innovation Fund will also roll out a specific CCfD programme.

Finally, waste management and the efficient use of natural resources (circular economy), can make a significant contribution to reducing greenhouse gas emissions. The European economy notably produces a large amount of urban and industrial waste, and the sector generates 3% of EU emissions. Landfills are a main source of methane emissions. Investing in more sustainable waste management systems, shifting to the reuse and recycling of materials, and designing products in a way that minimise waste production, are all essential. The transition to a circular economy also allows the reduction of upstream emissions, as a lower amount of materials is processed in industry (Agora Energiewende 2022c). Circular economy investment also contributes to reducing the material consumption footprint and the extraction of natural resources (e.g. wood, water, minerals). The investment needs in this area are not always included in the assessments of climate mitigation scenarios, because material efficiency is not always modelled directly. For instance, the European Commission (2020a) offers separate estimates of the investment needs for a circular economy.

8.1.3 Transport

Domestic transport generates 22% of the EU greenhouse gas emissions and international aviation and maritime transport contribute to another 7%. Road transport vehicles are notoriously a major source of oil demand and directly consume 48% of the total oil and petroleum products in the EU.9 While they are the most common type of transport vehicle in circulation, private cars account for only around 44% of domestic and international transport emissions (McKinsey 2020). Light- and heavy-duty trucks release significant amounts of emissions, and account for around 27% of the sectoral total. Transportation is the only sector that has increased greenhouse gas emissions since 1990 (McKinsey 2020) and the demand shift towards heavier cars, i.e. SUVs, has offset fuel economy gains over the last few years (IEA 2021b).

8.1.3.1 Private Transport

Zero-emission vehicles (including fully electric) are still more expensive than their equivalents with internal combustion engines, and subsidies are necessary to ensure a rapid uptake of these technologies. Even if electric cars already offer cost savings while driving in several parts of Europe, their higher price tag and charging infrastructure requirements make them less attractive to most customers. Different forms of subsidies, i.e., purchase discounts and waivers from ownership taxes, are already in place across the EU and should continue as long as price parity is reached. According to BloombergNEF (2021), price parity between battery EVs and ICE cars for the large and medium car segments will be reached significantly earlier than for small cars (2022 and 2023 respectively, instead of 2027 for small cars). However, the timeline is now more uncertain, given the recent sharp increase in the cost of producing batteries and other electric car components.

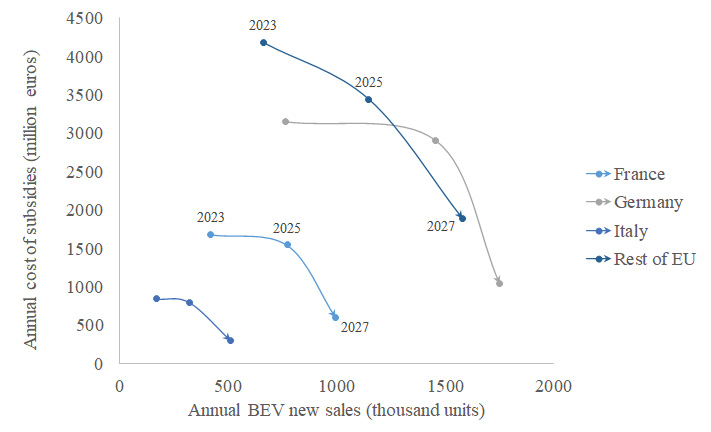

There are no comprehensive assessments of the fiscal costs of subsidising electric vehicles in the EU, but it is possible to understand the order of magnitude with an example for battery electric cars. There are three components of the total fiscal cost: the subsidy for each car sold (including various tax benefits), the number of annual sales, and the percentage of car models receiving support. In fact, market segments where EVs are already competitive may not be eligible for subsidies going forward. Fig. 8.4 Cost of electric car subsidy programmes and annual sales of BEVs. shows how the cost of the subsidy scheme evolves as support is gradually reduced while the share of EVs rises. We model a 6000-euro subsidy in 2023 that is reduced to 5000 euros in 2025 and to 3000 euros in 2027. The share of supported models also declines over time. Overall, the direct fiscal cost of the car purchase scheme in all EU countries does not exceed 10 billion euros per year, which is less than 0.1% GDP.

Fig. 8.4 Cost of electric car subsidy programmes and annual sales of BEVs.

Source: author’s calculation. Note: the cost for 2023 includes a 2000-euro subsidy for the purchase of new plug-in hybrid electric cars.

Private and public charging stations and other infrastructure for alternative fuels are essential for the rapid diffusion of clean vehicles. Millions of charging points will have to be installed in homes, offices and public areas for shared use. The majority should be slow chargers at home (below 22 kW), which cost less than a couple of thousand euros including installation (BloombergNEF 2021). Ultra-fast and fast chargers are much more expensive, but their cost is expected to drop significantly over the next years and they are needed in lower numbers. In a 2050 net zero emissions scenario, BloombergNEF (2022) estimates annual investment in private and public charging infrastructure in Europe should reach 11 billion US dollars (around 10 billion euros) in the period 2026–2030, of which 4 billion US dollars will be for public charging stations.10 Deployment subsidies therefore should not put a significant burden on public finances. A back-of-the envelope calculation with a support rate of 50% in 2022–2025 and 30% in 2026–2030, similarly to OBR (2021), gives an estimate of public cost at around 3.1 billion euros per year in 2022–2030.

8.1.3.2 Public Transportation

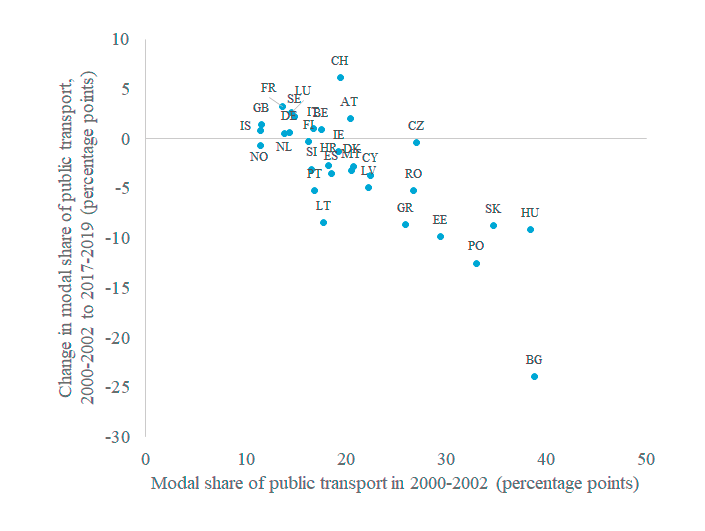

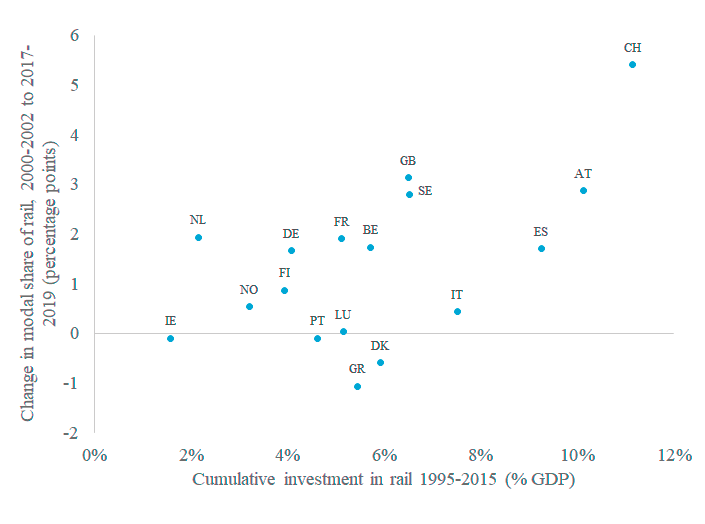

Modal shift is another way of reducing greenhouse gas emissions and local pollution from road transport and air travel. For climate policy, an increasing use of collective transportation is important to reduce emissions beyond what the switch to alternative zero emissions vehicles can achieve. The share of passenger-kilometres travelled by buses and trains out of the total kilometres travelled within the EU has slightly declined from 18% in 2000–2002 to 17.2% in 2017–2019. This aggregate figure hides quite stark differences across EU countries, as there has been a general decline in former communist countries, where individuals switched to private transportation, and a small increase in Western Europe (e.g. Italy, France, Austria, Sweden). Panel A of Fig. 8.5 The evolution of public transport use. shows that, over the last twenty years, countries that started with a high usage level of rail and public transportation in the early 2000s have shifted most dramatically to passenger cars. Panel B focuses on Western Europe and rail transport. It displays the relationship between the cumulative investment in rail networks between 1995 and 2015 and the change in the share of trains in inland passenger transport after the year 2000. The shift to rail transport has been limited to a few percentage points even in countries like Austria, Spain and Switzerland that invested quite a lot in their rail networks.

|

|

Fig. 8.5 The evolution of public transport use.

Source: author’s calculations on Eurostat and OECD data. Note: Cumulative investment in percentage of 2019 GDP.

Grants from central and local governments make up a large fraction of the capital expenditures in rail and local public transport in most EU countries. The European Commission assessment of the TEN-T additional investment needs, which includes cross-country road, rail and other transport infrastructures, evaluates the share of national and EU funding as being at 93% (European Commission 2021b). In Germany, non-repayable public grants contributed to 81% of Deutsche Bahn Group’s investment in the rail network and services in 2021 (9 billion out of 11.1 billion euros).11 In Italy, the Gruppo Ferrovie dello Stato Italiane invested 9.98 billion euros in 2021, 77% of which was financed through public grants.12 In France, around 50% of the capital expenditures of Groupe SNCF in 2021 and 2020 were subsidised by national and local public budgets.13 On top of capital expenditures, governments also subsidise the operation and maintenance expenditures to different degrees. This kind of spending will increase, as governments will improve the quality of public transport services while keeping them affordable and convenient vis à vis other modes of transport.

8.1.4 Public Spending Needs by 2030 in the EU

Table 8.1 Investment and public spending needs for the EU27 in 2021–2030. shows a selection of investment needs estimates for individual sectors in 2021–2030 and their associated public spending needs. When the fiscal cost is from an investment grant or a similar policy, a coefficient is applied to the investment figure. The coefficients are the share of capital expenditures paid by the public sector, and they are derived from the literature or the observations discussed in the previous sections. In Table 8.2, the assumptions for the base case are compared to those used in a few other studies. When the spending need is a recurring expenditure, like opex support, the amount of public spending is calculated separately. For the case of private transport, namely passenger cars and commercial vehicles (including trucks, tractors, and motor coaches), the public spending figure covers tax incentives and subsidies for vehicle purchases and subsidies to install charging and refuelling points.14 The public shares are applied to the additional investment needed over this decade, not to the total levels. The results of Table 8.1 Investment and public spending needs for the EU27 in 2021–2030. therefore underestimate the public investment needs if the share of public support will be higher than in the past.

Table 8.1 Investment and public spending needs for the EU27 in 2021–2030.

|

Sector |

Annual investment gap (billion euros p.a.) |

Source |

Public share (%) |

Public spending needs (billion euros per year) |

|||||

|

|

C |

|

C |

L |

H |

C |

L |

H |

|

|

Power generation (capex) |

50 |

Author’s calculation |

5% |

2% |

10% |

3 |

1 |

5 |

|

|

Power generation (opex) |

Author’s calculation/Agora Energiewende (2022b) |

3 |

1 |

5 |

|||||

|

Power grids |

33 |

European Commission (2022b) |

30% |

10% |

50% |

10 |

3 |

16 |

|

|

District heating |

25 |

Mathiesen et al. (2019) |

40% |

20% |

60% |

10 |

5 |

15 |

|

|

Residential and non-residential buildings15 |

165 |

European Commission (2021a; 2022b) |

45% |

35% |

65% |

74 |

49 |

120 |

|

|

New fuels production and distribution |

7 |

European Commission (2021a; 2022b) |

40% |

30% |

50% |

3 |

2 |

3 |

|

|

Industry (capex) |

19 |

European Commission (2021a; 2022b) |

30% |

20% |

40% |

6 |

4 |

8 |

|

|

Industry (opex) |

Author’s calculation/Material Economics (2022) |

4 |

3 |

5 |

|||||

|

Waste/Circular economy |

42 |

European Commission (2020a) |

50% |

30% |

60% |

21 |

13 |

25 |

|

|

Private transport |

Author’s calculation |

20 |

15 |

25 |

|||||

|

Rail and public transport (TEN-T Core) |

33 |

European Commission (2020a) |

95% |

80% |

100% |

31 |

26 |

33 |

|

|

Rail and public transport (national) |

76 |

European Commission (2020a) |

85% |

60% |

95% |

65 |

46 |

72 |

|

|

Total (% GDP) |

450 (3.2) |

249 (1.8) |

168 (1.2) |

333 (2.4) |

|||||

|

Public share capex (excl. private transport) |

54% |

36% |

72% |

||||||

Note: Monetary values are expressed per year and in billions of euros at 2019 prices. Investment gaps are the difference between the required spending in the periods 2021–2030 and 2011–2020. Columns indicate the alternative scenarios, where (C) is the central case, (L) is the low public cost and (H) is the high public cost scenario. In the European Commission (2021a) modelling, the (L) scenario corresponds to the MIX-CP scenario, whereas (H) corresponds to the REG scenario. The different investment needs for buildings are reported accordingly.

The public spending needs are calculated for a Central scenario and two other scenarios are added to provide nuance to the results. In a low public cost case (L), the policy mix uses less central and local government financing of infrastructures, more carbon pricing and less subsidies, while the high public cost case (H) assumes the opposite. The alternative scenarios show that the size of the climate public spending will depend quite significantly on how policies are designed, in particular in the buildings and transport sectors. It becomes clear that minimising the use of non-repayable grants and subsidies should be a priority, while keeping the decarbonisation incentives of households and firms fixed to the target.

Table 8.2 Public sector shares of additional costs. compares the assumed shares to other studies. EIB (2022) reviews the National Energy and Climate Plans for all EU countries and find an average (unweighted) public share of investment needs equal to 45%. As the plans refer to the old 2030 emission target (40% reduction), the shares are likely to underestimate the public role in achieving the more ambitious current target. While the sectoral assumptions of the Central scenario are similar to those of OBR (2021), the aggregate share (26%, not reported) differs because of the different weights of power and car investment costs in the computation.

Table 8.2 Public sector shares of additional costs.

|

Central scenario |

OBR (2021) |

EIB (2022) /NECPs |

IEA (2021) |

|

|

Expenditure |

Capex |

Capex and opex |

Capex |

Capex |

|

Region |

EU |

UK |

EU |

AE |

|

Total |

54% |

45% |

||

|

Sectoral details |

||||

|

Power sector |

15% |

7% |

17% |

|

|

o/w: Power generation |

5% |

- |

||

|

o/w: Power grids |

30% |

10% |

||

|

District heating |

30% |

90% |

||

|

Residential buildings |

45% |

44% |

||

|

Non-residential buildings |

45% |

43% |

||

|

Industry |

30/50% |

50% |

||

|

Private transport |

20% |

|||

|

Rail and public transport |

95/90% |

85/50% |

The estimate of the total climate public spending that is needed in 2021–2030 in the EU is 1.8% of 2019 GDP. Additionally, there are other fiscal costs that should not be neglected but are harder to quantify, such as spending to protect the most vulnerable parts of the economy from policy-induced unemployment and higher living costs. Low-income households facing carbon pricing and other costly regulations will have to be supported financially. One way to assess the cost of such social support is to consider the recycling of carbon pricing revenues. According to Held et al. (2022), compensating households in the lower two income quintiles in all MS requires 23.4% of revenues from the proposed EU ETS for road transport and buildings. These resources therefore would not contribute to closing the climate investment gap, unless the aid were in the form of investment grants. At the same time, a new green workforce will have to be trained and workers displaced from shrinking industries will need help to transition to new jobs. Krebs and Steitz (2021) estimate Germany’s spending needs in climate-related education and reskilling by 2030 at 20 billion euros. Finally, the decline in consumption of fossil fuels will erode energy tax revenues, especially from motor fuels. However, the effect is likely to be small before 2030 (OBR 2021).

8.2 Conclusion

The transition to climate neutrality by 2050 will be achieved only if green investment in the EU is scaled up quickly within the next few years. Closing the climate and energy security investment gap of 450 billion euros per year in 2021–2030 will require governments to strengthen environmental regulation and make more funds available to support the transition. The analysis presented in this paper suggests that the annual public spending needs to support green investment stand at around 250 billion euros (1.8% of 2019 GDP) over this decade. Without public transport investment, the figure stands at 153 billion euros (1.1% of GDP). Almost three quarters of these spending needs are in the buildings and transport sectors. The necessary public expenditures could be significantly higher or lower, depending on how policies are designed with respect to the use of carbon pricing and instruments to leverage private capital. Moreover, the impact of this spending on public debt and budget balances will depend on the multiplier effects on economic activity and tax receipts. This is a key component in the assessment of the fiscal implications of climate change policies.

The EU average of public spending needs is however not representative for all countries. Reviewing the results from the NECPs, which refer to the old 2030 target (-40%), EIB (2022) shows significant country variation not only with respect to investment needs, but also to expected public share of climate expenditure. Krebs and Steitz (2021) estimate a public spending gap of 1.3% of GDP in 2021–2030 for Germany. Agora Energiewende (2022d) derives national estimates of the public spending gaps and shows how they compare with the EU funds that each member state is expected to receive in the current EU budget period. The higher investment needs, as a percentage of GDP, in Central and Eastern Europe are in general well-matched by EU funding. In Southern Europe, the significant EU support of climate action through the EU Budget and RRF still leaves national climate spending gaps of around 1% of GDP annually. To ensure all EU countries deliver on the 2030 climate goals, without excessive political and social costs, the EU economic and fiscal governance should monitor the green spending and remaining gaps in the evaluation of the necessary fiscal adjustments. As most of these expenditures are in a few sectors, i.e. buildings and transport, even narrowly defined green spending exemptions to fiscal rules could help. In the long term, the EU will need an instrument like the RRF to continue sharing some of the cost of decarbonisation, and to provide fiscal support to those countries most in need.

References

ACEA (2022) “Share of Alternatively-powered Vehicles in the EU Fleet, per Segment”, ACEA, https://www.acea.auto/figure/share-of-alternatively-powered-vehicles-in-the-eu-fleet-per-segment/.

Agora Energiewende (2021) 10 Benchmarks for a Successful July Fit for 55 Package. Berlin: Agora Energiewende, https://www.agora-energiewende.de/en/publications/10-bench marks-for-a-successful-july-fit-for-55-package/.

Agora Energiewende (2022a) Klimaschutzverträge für die Industrie transformation: Kurzfristige Schritte auf dem Pfad zur Klima-neutralität der deutschen Grundstoffindustrie. Berlin: Agora Energiewende, https://www.agora-energiewende.de/veroeffentlichungen/klimaschutzvertraege-fuer-die-industrietransformation-gesamtstudie/.

Agora Energiewende (2022b) Regaining Europe’s Energy Sovereignty. Berlin: Agora Energiewende, https://www.agora-energiewende.de/en/publications/regaining-europes-energy-sovereignty/.

Agora Energiewende (2022c) Mobilising the Circular Economy for Energy-intensive Materials. Berlin: Agora Energiewende, https://www.agora-energiewende.de/en/publications/mobilising-the-circular-economy-for-energy-intensive-materials-study/.

Agora Energiewende (2022d) Delivering RePowerEU: A Solidarity-based Financing Proposal. Berlin: Agora Energiewende, https://www.agora-energiewende.de/en/publications/delivering-repowereu/.

BloombergNEF (2021) “Long-Term Electric Vehicle Outlook 2021”, Bloomberg New Energy Finance.

BloombergNEF (2022) “EV Charging Infrastructure Outlook 2022”, Bloomberg New Energy Finance.

BPIE (2020) Covid-19 Recovery: Investment Opportunities in Deep Renovation in Europe. BPIE, https://www.bpie.eu/publication/covid-19-recovery-investment-opportunities-in-deep-renovation-in-europe/.

Bódis K., Ioannis Kougias, Arnulf Jäger-Waldau, Nigel Taylor, Sándor Szabó (2019) “A High-resolution Geospatial Assessment of the Rooftop Solar Photovoltaic Potential in the European Union”, Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 114, October 2019, 109309, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2019.109309.

Boston Consulting Group (2022) “Achieving Energy Security in the EU”, Boston Consulting Group, https://www.bcg.com/publications/2022/achieving-energy-security-in-the-eu.

CEER (2021) Status Review of Renewable Support Schemes in Europe for 2018 and 2019. Council of European Energy Regulators, https://www.ceer.eu/res-status-review#.

CEER (2022) Report on Regulatory Frameworks for European Energy Networks 2021. Council of European Energy Regulators, https://www.ceer.eu/documents/104400/-/-/ae4ccaa5-796d-f233-bfa4-37a328e3b2f5.

Economidou, M., B. Atanasiu, C. Despret, J. Maio, I. Nolte, O. Rapf, and S. Zinetti (2011) Europe’s Buildings under the Microscope. A Country-by-Country Review of the Energy Performance of Buildings, Brussels: BPIE.

Economidou, M., V. Todeschi, and P. Bertoldi (2019) Accelerating Energy Renovation Investments in Buildings. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union, http://dx.doi.org/10.2760/086805.

Element Energy (2022) The Consumer Costs of Decarbonised Heat. Cambridge: The European Consumer Organization, https://www.beuc.eu/sites/default/files/publications/beuc-x-2021-111_consumer_cost_of_heat_decarbonisation_-_report.pdf.

Energy Transitions Commission (2020) Making Mission Possible—Delivering a Net-Zero Economy, Energy Transitions Commission, https://www.energy-transitions.org/publications/making-mission-possible/.

European Commission (2019) Comprehensive Study of Building Energy Renovation Activities and the Uptake of Nearly Zero-energy Buildings in the EU. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union, https://doi.org/10.2833/14675.

European Commission (2020a) Commission Staff Working Document—Identifying Europe’s Recovery Needs, SWD (2020) 98, CELEX: 52020SC0098(01).

European Commission (2020b) Commission Staff Working Document—2030 Climate Target Plan Impact Assessment, SWD (2020) 176, CELEX: 52020SC0176.

European Commission (2021a) Revision of the Renewable Energy Directive (REDII)—Impact Assessment, COM (2021) 557, CELEX: 52021PC0557.

European Commission (2021b) Revision of the TEN-T Regulation—Impact Assessment Report, COM (2021) 812, CELEX: 52021PC0812.

European Commission (2021c) Revision of the ETS Regulation, COM (2021) 551, CELEX: 52021PC0551.

European Commission (2022a), Report on the Implementation of the Recovery and Resilience Facility, COM (2022) 75, https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/854d57 5a-9959-11ec-83e1-01aa75ed71a1.

European Commission (2022b) RePowerEU plan—Staff working paper, SWD (2022) 230, https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/12cf59a5-d7af-11ec-a95f-01aa75ed71a1.

European Investment Bank (2022) EIB Investment Report 2021/2022: Recovery as a Springboard for Change, Luxembourg: European Investment Bank, http://dx.doi.org/10.2867/82061.

Goldman Sachs (2022) Electrify Now: The Rise of Power in European Economies, https://www.goldmansachs.com/insights/pages/electrify-now-the-rise-of-power-in-european-economies.html.

Held, B., C. Leisinger, M. Runkel, G. CAN-Europe, Deutschland eVKA, and WWF Deutschland (2022) Criteria for an Effective and Socially Just EU ETS 2, Report 1/2022, https://www.germanwatch.org/sites/default/files/criteria_for_an_effective_and_socially_just_eu_ets_2.pdf.

ICCT (2021) A Global Comparison of the Life-cycle Greenhouse Gas Emissions of Combustion Engine and Electric Passenger Cars, https://theicct.org/publication/a-global-comparison-of-the-life-cycle-greenhouse-gas-emissions-of-combustion-engine-and-electric-passenger-cars/.

IEA (2021a) Financing Clean Energy Transitions in EMDEs. Paris: IEA Publications, International Energy Agency, https://www.iea.org/reports/financing-clean-energy-transitions-in-emerging-and-developing-economies.

IEA (2021b) Global SUV Sales Set Another Record in 2021, Setting back Efforts to Reduce Emissions. Paris: IEA Publications, International Energy Agency, https://www.iea.org/commentaries/global-suv-sales-set-another-record-in-2021-setting-back-efforts-to-reduce-emissions.

IEA (2021c) World Energy Outlook 2021. Paris: IEA Publications, International Energy Agency, https://www.iea.org/reports/world-energy-outlook-2021.

IEA (2022) Renewable Energy Market Update—May 2022. Paris: IEA Publications, International Energy Agency, https://www.iea.org/reports/renewable-energy-market-update-may-2022.

IRENA (2021) Renewable Power Generation Costs in 2020. Abu Dhabi: International Renewable Energy Agency, https://www.irena.org/publications/2021/Jun/Renewable-Power-Costs-in-2020.

IRENA and CPI (2018) Global Landscape of Renewable Energy Finance 2018. Abu Dhabi: International Renewable Energy Agency, https://www.irena.org/publications/2018/jan/global-landscape-of-renewable-energy-finance.

IRENA and CPI (2020) Global Landscape of Renewable Energy Finance 2020. Abu Dhabi: International Renewable Energy Agency, https://www.irena.org/publications/2020/Nov/Global-Landscape-of-Renewable-Energy-Finance-2020.

Linden, A. J., F. Kalantzis, E. Maincent, and J. Pienkowski (2014) Electricity Tariff Deficit: Temporary or Permanent Problem in the EU? (No. 534), Directorate General Economic and Financial Affairs (DG ECFIN), European Commission Publications Office, https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2765/71426.

Krebs, T. and J. Steitz (2021) “Öffentliche Finanzbedarfe für Klimainvestitionen im Zeitraum 2021–2030”, Forum for a New Economy Working Papers 3–2021, https://www.agora-energiewende.de/veroeffentlichungen/oeffentliche-finanzbedarfe-fuer-klimainvestitionen-2021-2030/.

Material Economics (2022) “Scaling Up Europe, Bringing Low-CO2 Materials from Demonstration to Industrial Scale”, https://materialeconomics.com/publications/scaling-up-europe.

Mathiesen, B. V., N. Bertelsen, N. C. A. Schneider, L. S. García, S. Paardekooper, J. Z. Thellufsen, and S. R. Djørup (2019) Towards a Decarbonised Heating and Cooling Sector in Europe: Unlocking the Potential of Energy Efficiency and District Energy. Aalborg: Aalborg Universitet, https://vbn.aau.dk/en/publications/towards-a-decarbonised-heating-and-cooling-sector-in-europe-unloc.

McKinsey (2020) Net Zero Europe: How the European Union could achieve net-zero emissions at net-zero cost, https://www.mckinsey.com/capabilities/sustainability/our-insights/How-the-European-Union-could-achieve-net-zero-emissions-at-net-zero-cost.

OECD (2021) Effective Carbon Rates 2021: Pricing Carbon Emissions through Taxes and Emissions Trading. Paris: OECD Publishing, https://doi.org/10.1787/0e8e24f5-en.

OBR (2021) Fiscal Risk Report—July 2021. London: Office for Budget Responsibility, https://obr.uk/frs/fiscal-risks-report-july-2021/.

Trommsdorff, M., S. Gruber, T. Keinath, M. Hopf, C. Hermann, and F. Schönberger (2020) Agrivoltaics: Opportunities for Agriculture and the Energy Transition-A Guideline for Germany. Freiburg: Fraunhofer ISE, https://www.ise.fraunhofer.de/content/dam/ise/en/documents/publications/studies/APV-Guideline.pdf.

Wouter Nijs, Dalius Tarvydas, and Agne Toleikyte (2021) EU Challenges of Reducing Fossil Fuel Use in Buildings—The Role of Building Insulation and Low-carbon Heating Systems in 2030 and 2050. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union, https://doi.org/10.2760/85088.

1 Based on Eurostat data.

2 Baccianti and Odendahl (2022). Values in 2020 prices.

3 Values are capacity-weighted averages from CEER (2021). These figures only cover the pool of supported plants and they do not reflect the fact that more and more RES projects do not receive any direct financial support.

4 The 2019 figure is from Eurostat and the indicator is defined as individuals that have an equivalised disposable income below the risk-of-poverty threshold (which is set at 60% of the national median equivalised disposable income) or those that have severe material and social deprivation.

5 See for instance the European Commission’s report Prices and costs of EU energy—Ecofys BV study, Annex 3.

6 European Commission’s EU buildings factsheet. Data refer to 2013.

7 Author’s calculation based on European Commission’s EU buildings factsheet data.

8 2017 data from IEA.

9 Based on Eurostat data.

10 Values refer to the EU, Norway and Switzerland.

12 Relazione finanziaria annuale 2021.

13 See Groupe SNCF’s Rapport financier annuel 2021 and Fipeco’s Le coût de la SNCF pour le contribuable.

14 The calculation for commercial vehicles is based on Eurostat data. In the Central scenario, around 15% of the fleet of goods vehicles and trailers is replaced with low-carbon alternatives and receives individual subsidies in the range of 10–20 thousand euros on average over the period. 40% of motor coaches and buses are instead replaced and receive an average subsidy of 10 thousand euros. The total cost of such programmes across the EU would be approximately 10 billion euros per year during the period 2021–2030.

15 It is assumed that governments support the full cost of home renovations for households earning below 60% of the median equivalised income (18.4%) and for public buildings (30% of non-residential buildings). The public support for home renovations for remaining households is 30% in EU countries with GNI per capita above the EU average and 40% in the others. Grants for the renovation of private non-residential buildings cover 23% of the investment. The investment gap is 141 billion euros in the low public cost scenario and 184 billion euros in the 184 billion euros in the high public cost scenario. See note below table for correspondence with the European Commission scenarios.