10. ‘How much easier it is to honour the dead than to value the living’—The Tale of Trevithick’s Tower

© 2023 Paul Farmer, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0329.12

The new show would be the result of all we now knew about ourselves, all the performing experience we had accrued and new opportunities we had perceived since we put together One & All!

To understand these developments, a key issue was those ‘levels of pretence’—the principle derived from McGrath’s observations on the sophistication of popular engagement with issues of identity in the performance of pantomime.1 Thinking about our experiences of performing One & All!, some issues could be investigated through the unity of playwrights and performers; for example, who were we being when we were narrating? When we spoke directly to the audience was it as ourselves, like a singer announcing the next song? Or were we being some kind of neutral nobody? What about our accents, postures, mannerisms? We were still performing but were we still ‘acting’? We were speaking lines of a script in a manner that was actorly, using the skills of projection and engagement—we were making it clear and convincing; but how much was pretence and how much of it was just being? Was this an issue of ‘gestus’—that the lines were said with a certain underlying attitude that meant we were acting not-acting?2

Perhaps all pretence really was being dropped pro tem. The audience knew we meant what we said, we believed it to be true. When we put together our perceived truths to make arguments it was still clear that this is what we were doing, no deception was being attempted. We were not newsreaders trying to evoke tablets of stone. But in the substantial part of One & All! that was narration, were we making the most of the possibilities available to us?

We felt it was necessary for the form, in the attempt to communicate the content we believed to be vital, that we could direct this necessary information to the audience—statistics, facts, quotations, contexts. Apart from direct speech we could have used Brechtian captions or signs, but we could not rely on the blackout qualities of non-theatre spaces to allow projections, and anyway we did not have access to the technology, or the will to use it. With Miracle Theatre, Sue and I had participated in rudimentary and very early use of video in theatre and we did not feel this was a path we wanted to follow. Our beliefs here we shared with those expressed by McGrath:

For one further–perhaps the most important–feature of theatre as a form is that its dimensions are essentially those of the human figure, its communication essentially between one group of people and another present in the same space.3

We felt it fundamental to embody this communication. Despite the changes in and availability of technology, this is still my position. I do not believe in projected scenery or recorded music, throat mics, and amplification, just people alive in the presence of other humans in the evocation of the aesthetic space.4

How could we develop the possibilities of these human relationships in the perpetration of our form of theatre? What other opportunities were there within our tatty aesthetic? We shared some of the viewpoints implicit in Grotowski’s ‘Poor Theatre’, which Mark had explored in workshops in Exeter, though the kind of cult-like discipline urged by Grotowski was alien to A39. We shied away from all such hermetic approaches—even Brecht’s own tedious workshop exercises of endless mimicry in movement, Peter Brook’s neo-votive communes, as well as Grotowski’s physical tortures.5 Our theatre was about finding itself within our everyday relationships; it was not just of us but of our lives beyond A39, of the daily experience of being of Cornwall. Besides what we said and performed, it was the communications beyond words, the spaces between places, the long roads towards the sunset and the End of Land, the high ground diversions from holidaymaker traffic jams over and along Cornwall’s spine to suddenly materialise in the centre of St Ives or the streets of Penzance. It was the clean moist air of the Atlantic that barely acknowledged Cornwall’s existence but blew and beat over and through her to bend the lichen-covered trees. A39’s theatre was all of us all of the time, whatever we were doing. This was its validity and credibility. We lived this place. It was in us whenever we were devising, rehearsing, or performing. That was why its nature was becoming clearer as time passed: place and work and we were inseparable. That was what was available to us in our poverty without any external means to surmount Cornwall’s demands. It made us the real thing.

We were performers of the room. It could suddenly just happen, completely unexpectedly. It was like a kind of conjuring. This quality was helped by the growing significance of our cabaret act, while our street theatre work diminished. The creation of these short, discrete pieces that often occurred within musical rather than theatrical contexts was very influential on the creation of the new play, The Tale of Trevithick’s Tower. While still immediate, they were growing in ambition and increasingly avant-garde in an austere, punk kind of way. The average age of our audiences became ever younger. I am still accosted by those who spent their youths watching The A39s (the name we went under in non-theatrical contexts), which makes me feel very old.

From the first, there had been a ‘recitative’ (rhymes with Steve) quality in One & All! that corresponded, weirdly, to the storytelling aspect of operas that develops the narrative between arias. ‘Recitative’ singing had always sounded to me like an attempt to excuse a failure of composition, dialogue just pretending to be sung to a tune that remains the same throughout the work. To the opera hater, among whose ranks I have to include myself, it is the most annoying aspect even of an artform the perpetrators of which seem to flaunt its elitism and irrelevance.

But there was a correspondence here to the formality of our delivery of narration. We had chosen through instinct to maintain this formality as an alienation technique (Brecht’s ‘V-Effekt’), but meanwhile there we were in costume, so therefore not ‘ourselves, performing’ but characters whose defining quality was authority; or rather, as there were no contradictions in these portrayals, as stereotypes of authority.

There is nothing wrong with the use of stereotypes for the purposes of drama. Theatre ‘characters’ and ‘stereotypes’ are equally artificial, equally a tool of pretence; it’s just that one of these figures will display ‘realistic’ internal alterities and the other will not. The stereotype is actually the more honestly presented stage inhabitant as it does not pretend to reality but is presented as a symbol. Hence, One & All! repeatedly featured Lord Knacker, with his top hat and tailcoat, as Mineral Lord, Adventurer, capitalist, and ‘patriot’, his nature identified through the knowledge the audience brought in with them of the semantics of the genre (cf. Robert Altman’s semantic/syntactic theory of film genre6). Through our costume in the narrative sections and our formality, we were placing authority with the working-class miners and identifying the play as their version of history. Would this approach also underpin a Brechtian street-scenic ‘demonstration’ of the events of Trevithick’s life?

Thought and discussion originated another way to go that could obviate any ‘ourselves, performing’ or ‘transfer of authority’ confusion—there were aspects of these approaches that had uncomfortable resonances with McGrath’s ‘Old Hen’ form. We could push the whole show up one ‘level of pretence’ and remove any implied authority figures: no godlike ‘newsreaders’, even working-class versions; rather than ask audiences to take anyone on trust, we could insist they distrusted everybody and free them to ascribe authority where they felt it belonged. The new play would not be presented by anyone like us but by characters whose information obviously could not be taken entirely at face value.

So we formulated the new show not as a play at all, but as a public meeting—the logical conclusion to McGrath’s insistence, with which we agreed, that:

Theatre is the place where the life of a society is shown in public to that society…. It is a public event and it is about matters of public concern…. [T]heatre is by its nature a political form, or a politicising medium….7

Fig. 25. Tony Duckels’s poster for The Tale of Trevithick’s Tower, screen printed by Lucy Kempton. This one advertised the premier at Camborne Trevithick Day 1986. Antony Duckels (CC BY-NC 4.0.)

The material the new play would be dealing with was known in part by many Cornish people: Trevithick, the great innovator cheated out of his due recognition by ‘history’, or something. It’s a tale that has much resonance with the Cornish, their own collective engineering and hard-rock achievements disregarded and forgotten, their spoils systematically taken away. In dealing with this feeling, we would out it and turn it into a political discussion.

As a means to this, we seized on an issue that was the subject of real public meetings at the time. The plan was afoot (and eventually realised) to take over Truro City Hall, a cavernous, echoing space in a conurbation of old municipal masonry right at the city’s heart, much used for flea markets and gigs, and turn it into a prestigious theatre. There was angry opposition to this from a number of different viewpoints. The perspective we shared was that the urge to a prestige bourgeois culture palace was a symptom of a distorted metropolitan, centralising vision of Cornwall that would later be referred to by the Cornish Social and Economic Research Group (CoSERG) in their influential book Cornwall At The Crossroads8 as an outsider’s patronising ‘Bring them Shakespeare and streetlights!’ attitude. It assumed Cornwall to be a backward, uncultured place that needed to be more like the Home Counties from which many of those hosting such assumptions had come. (This source and such insights were to be central in A39’s third touring play Whole New Towns.)

We felt that the decentred nature of Cornwall, with multiplex small settlements, each with their own character and institutions, was actually what a better vision of the UK—and indeed the ‘developed’ world—would look like. One of the reasons we detested the Arts Council’s new Glory of the Garden policy was that it specifically favoured the provision of the arts in urban ‘Centres of Excellence’ (the capital letters being urgently obligatory).9 Those living in rural outer darkness would pay occasional visits in their Sunday best, pausing in the municipal car park to brush the straw off each other’s clothes before achieving their access to officially approved Excellence. We believed that it was no coincidence that Cornwall, without a designated, prestige cultural centre, could support—albeit in poverty—so many more theatre companies than the much bigger, much more populated, much richer Devon that looked to Plymouth and Exeter and even Bristol.

As eventually realised the ‘Hall for Cornwall’, as it was named, would have only a single auditorium and no studio theatre; so unless Cornwall’s own companies could draw a thousand people to drive to Truro, equivalent to the capacity of dozens of village halls and an entire tour’s-worth of audience, this was no venue for us. And if we could exert such an attraction, what would we do then? Should we originate complete shows for a single performance? A model for the performing arts was imposed implicitly and unexamined, and it is obvious that this venue was not intended to host anything ontologically responsive to Cornish cultural conditions. It was instead designed to import theatre; it was to replace the Cornish companies on the supposition that what we did had no value, although this formulation certainly flatters the amount of analysis that went into the scheme on the part of those for whom prestige is its own reward.

So our new show could do work in the present as well as enabling new analysis of the past. And for A39 to intervene in this way in this issue was nicely needling for all those who we would most enjoy to annoy, those who made no art themselves but for whom culture and artiness was a function of received wisdom and social status: of class.

We embellished their plan for our own purposes. Our public meeting was part of a fictional campaign to demolish the City Hall and build in its place the tower Trevithick designed in 1833 for a competition to commemorate the passing of the Reform Laws. Trevithick’s tower would have been a thousand feet high—higher than the Eiffel Tower, which would not be built for another fifty years—built of cast iron plates and topped with an enormous equestrian statue and containing its own steam engine to facilitate construction and later to power the lifts. We prepared questionnaires for our public meeting. I built a twelve-foot-high model of the tower out of cardboard using techniques I stole from Buckminster Fuller, but it was too tall for any of the venues we played and eventually we lost it.

To present the public meeting, we recruited three of Cornwall’s own ‘Great and the Good’ from the realms of our imagination. Sir John Doddle, to be played by Mark, would be an ex-Thatcherite cabinet minister, unmitigated capitalist, and urgent advocate of everything oppressive that was and had been. Sue would play his wife, Lady Julia Doddle: a genteel host of daytime television in the most unchallenging of women’s programming, a televisual equivalent of The Lady. I would play the Reverend Gerald P. Green, named after the Cluedo character and inspired by certain clerics I had met while helping to run The Crypt Centre. The Reverend represented Established piety, i.e. an ethics entirely contingent on the status quo that forswore any morality that rocked boats, all ethical discourse to be constrained by the interests of capitalist society. Wherever this clashed with conscience or the Bible, it was the Bible or conscience that would have to give way.

These three unreliable witnesses would conduct Brecht’s specified ‘demonstration’ of our subject, though they appeared to have made some quite bizarre decisions regarding the portrayal of Trevithick’s life. Trevithick himself appeared only once in the entire show, as a baby, when he was represented by Lady Julia’s capacious handbag. Our three hosts did not entirely see eye to eye on the interpretation of history, and the demonstration was made more difficult by Sir John’s insistence on describing historical events through the lens of contemporary Thatcherite ideology. In these terms, Trevithick’s failure to gain credit for his work and his death in poverty demonstrated his failure as an entrepreneur and thus was absolutely as he deserved. Any part of the demonstration that did not support this viewpoint (much of the formulation had been apparently the responsibility of the Reverend Green), Sir John would deliver with a sneer and disparaging comments.

The vicar evidently found Sir John’s red-in-tooth-and-claw Thatcherism distasteful, though failed to counter it substantially, as though it was really the vocabulary that was embarrassing and his disdain mostly aesthetic, as befits an Anglican Church described as ‘the Conservative Party at Prayer’. In his brusque dismissals and outright contempt, Sir John was very likely indeed to frighten the horses in a way that disturbed the illusion that there were any operative ethics at work in the British Raj, especially now it was reduced in scope to ruling over only those it despised the most: the British working class. The Reverend Green, like other High-Church figures, both symbolised and embodied the ‘spirituality’ of the state and also defined its limits, not defying establishment hypocrisy but sanctifying it through mystification.

Lady Julia mediated between the two theses of this low-dynamic dialectic and thus naturally synthesised the role of Chairwoman. In her suit, flesh-coloured tights, pearls, and blouse, all topped off with a Thatcherite hat (for there is such a thing), she was an establishment jolly-upper, verbally slapping down Sir John’s wilder ravings as though smacking the legs of a naughty child with the familiarity of a mother/lover; meanwhile steering Reverend Green with flattery and mock-humility.

Beginning the play with fulsome introductions by Lady Julia, our panel for the evening then moved into its scenes of the life of Trevithick through often ridiculous characterisations, returning to panel form with much mutual congratulation. As the show unfolded the techniques extended in scope, the commentary on the demonstrations coming to suggest that the presenters were losing control of their material and a story was coming to tell itself despite them (see Fig. 26).

Having pushed the execution of the play away from ourselves and into movement between the onion skins of ‘levels of pretence’, we could use these contemporary characters to critique contemporary society and government. The new script also took the time to develop scenes comedic in terms of dialogue as well as characterisation. The influence this had in relaxing the straightforward pedagogic drive of One & All! was reflected in the overall structuring of the show. This was partly through the demands of the form—public meetings and dramatic enactments seldom being technically rigorous in their unfolding—but also reflected a wish to take our time in performance. The virtuosity espoused by Brecht and backed by McGrath itself needed to unfold. And there was time for the characters to comment on their own performances and content.

Following the use of the Blue Blouse movement’s ‘Living Newspaper’ practice in the later iteration of One & All!, now we adopted their ‘Living Machines’ form—human bodies enacting the functioning of mechanisms, here mainly played for laughs.10 Musical segments also moved up and down the ‘levels of pretence’ (the move into song itself is a fundamental demonstration of the principle), some being sung by Sir John and Lady Julia and accompanied by the Vicar on voice and guitar, some by characters they were performing, some by a mixture of the two. We extensively used unaccompanied doo-wop style singing with hand percussion of a kind we made much use of on the street and in cabaret.

The transitions between levels were initially clearly and pointedly marked out, but once the practice was established it could occur quickly, without commentary. Progressively, new characters could stretch the outlines of those supposed to be performing them. There was something of a shamanic sense to these developments. If the audience was being led to these places by Sir John, Lady Julia, and the Reverend Green, what was happening to our protagonists that they could now encompass such knowledge and opinions when they seemed in themselves so constrained by the conventions that both bound and served them? This became part of the unfolding insight into the vicious economic system to which Trevithick was sacrificed: they could not recount a coherent story within its strictures, they had to break out of them in order to make any useful sense of the world.

Early in the second half the play seems to be employing the ‘Old Hen’ approach once again, like the grannie in One & All!. But here, in the story of John Bryant, it had a sting in its tail. The apparently homespun yarn became the story of machine breakers, Luddites. It was here that we pushed furthest from our ‘demonstrators’ for the evening, Lady Julia, Sir John, and the Vicar. Where the first half of the play ends with The British Entrepreneur, a new National Anthem proffered both for Trevithick’s time and Thatcher’s:

The poor must take their chance;

The hungry must just eat their cake;

Ye Rich, rise and advance!

We praise those on the make.

The Army and the Law,

Your property will store;

While ye make money for

The British Entrepreneur,

The British Entrepreneur!

the Bryant section contains its counter in The Great Enoch, named after the iron sledgehammer of the Luddite:

Our hammer is the Great Enoch,

The clever and the sly

have imprisoned all you common people,

Told you that you must not fight,

The clever weaklings know what’s right:

They make the Combination Laws,

That stop you talking on street corners,

Saying you won’t work for nothing.

Follow King Ludd! Smash their prisons!

Great Enoch will smash their prisons!

After this, in the Herland section, we reached down to tabula rasa in terms of ‘levels of pretence’, something like the three performers who had delivered the narrative segments of One & All!, but here delivering the lines not formally but dispassionately; the words alone doing their work in telling the story of how Trevithick transcended his own technology and conjured up something its materials could not sustain, the ghost of a technology to come.

Trevithick, father of the train,

Was driven from his home by steam

The first of all the Cousin Jacks to go.

In future days, the trains would come

With economics to each home

And turn them into Cornish caves.

Driven overseas by hunger

When the mines could work no longer

The Cornish folk embraced their brother.

And thus, we entered the retelling of Trevithick’s sojourn in Latin America.

As the programme noted, here lies the problem in portraying the life of Trevithick: it comes to seem unbelievable. It seems inconceivable that this same man, forgotten then beyond Cornwall, who invented the steam locomotive and innovation after innovation after innovation, then went to the Americas and found himself aide and engineer to El Libertador himself, Simon Bolivar, as he perpetrated a revolutionary war of liberation through the mountains, jungles, and cities of South America. This aspect of Trevithick’s life has received the least attention, perhaps because Trevithick’s earliest biographer, his son Francis Trevithick, was attempting to rehabilitate him and to overcome an unjust ignorance of this historical giant amongst the Victorian public. In this regard, the part of his life spent as a revolutionary republican freedom fighter would not be helpful. Queen Victoria would certainly not have been amused.

It could be argued that it was too much for us to include this story alongside everything else we had to portray, and that we should instead have made it the centre of another work. Maybe Sir John could have refused to play his part in portraying the rising of the oppressed against the tenets of imperialism. Perhaps we should just have shown that row. This would also have shortened the show, which was exhausting to perform. On the other hand, we would have been perpetuating the diminution of this important episode in a life. As it was, we went straight for maximum knockabout, complete with Simon Bolivar played by Groucho Marx and even a bit of Shakespeare (see Figs. 27, 28).

Most controversial in the performances tended to be the show’s almost-culmination with the singing of William Blake’s Jerusalem. There were complaints that we should finish such a Cornish play by inferring Cornwall’s inclusion in a song specifically about England. This indicated that the subtleties of the ‘levels of pretence’ were confusing some of the audience with regard to who was saying what to whom, but it fuelled some apposite after-show discussions: ‘Yeah, it’s wrong,’ we would say, ‘But that wasn’t us!’

The Tale of Trevithick’s Tower premiered in the Trevithick Arms in Camborne on the evening of Camborne Trevithick Day 1986. You could not get more Trevithick than that. We spent the day roaming the streets in our Panel characters and costumes, meeting the crowds in a royal-type walkabout, asking appropriately patronising questions, Sir John brusque and offensive, Lady Julia breezily ameliorating, the Reverend Green ever unctuous and prone to ad hoc, al fresco sermonising (see Fig. 29). The premiere was included in the Trevithick Day programme and publicity so for once the promotion was taken care of for us, though we had placed an item in The West Briton’s What’s On section and I had done an interview on Radio Cornwall.

We toured Trevithick around Cornwall. As the Tin Crisis worked through its grim unfolding, One & All! had a sustaining interest and we found ourselves touring both plays at the same time—a bizarre political repertory theatre. In performance, One & All! now seemed like a holiday compared with The Tale of Trevithick’s Tower, not only because the newer show was longer but also because of the nature of the performance Trevithick demanded. Virtuosity—it became apparent—when allowed the opportunity to run riot, is extremely tiring. And there was more conventional emotional range too. Because our main ‘demonstrators’ were not objective critics of the status quo but members of Britain’s ruling class junta, allowing their subjective variants on the hegemonic story of history to contend for the fruits of this public meeting led ultimately to them contradicting not only each other, but themselves; and it was draining to get them to this place nightly without logistical support.

An interesting insight came in the form of a report for South West Arts on Trevithick’s Tower in performance at the Blue Anchor in Helston, a favourite venue of ours. The report noted that the average age of the audience was under twenty-five, astoundingly for a theatre audience. It was a very positive report and the writer of it was thoughtful enough to get a copy to us. It was ignored. A39 would never receive Arts Council support, though by now we were receiving funding from Cornwall County Council and several District Councils, which sat better with us anyway. We were being funded by the locally elected representatives who came to see our shows and discussed them with us afterwards. The members of A39 were used to a lifetime of having been squarely Oppositional and it was a shock to realise that in the Cornwall of the 1980s it was possible to make such arguments within mainstream discourse, and for them to be valued.

As 1986 came to a close, big changes were coming for A39, as well as further developments in styles and forms that I will discuss in my second volume with reference to the shows Whole New Towns and Driving the New Road, and the development of ideas around playwriting per se. I will also discuss in detail the developing ideology and context of the work and its theoretical underpinnings; its nature as a Community Theatre practise and its position relative to the Community Arts movement; a comparison with other practice; and an assessment of what in the history of A39 may help others develop a political theatre practice for the decades to come.

Meanwhile, we had successfully created a new kind of theatre for Cornwall. We were getting through to new audiences and our arguments in terms of both theatrical and political ideologies were having some effect. We were professional theatre workers. We had made all we had out of our heads and ideas we read in books, and we had told some stories. In telling those stories, we had written this story of ourselves so far.

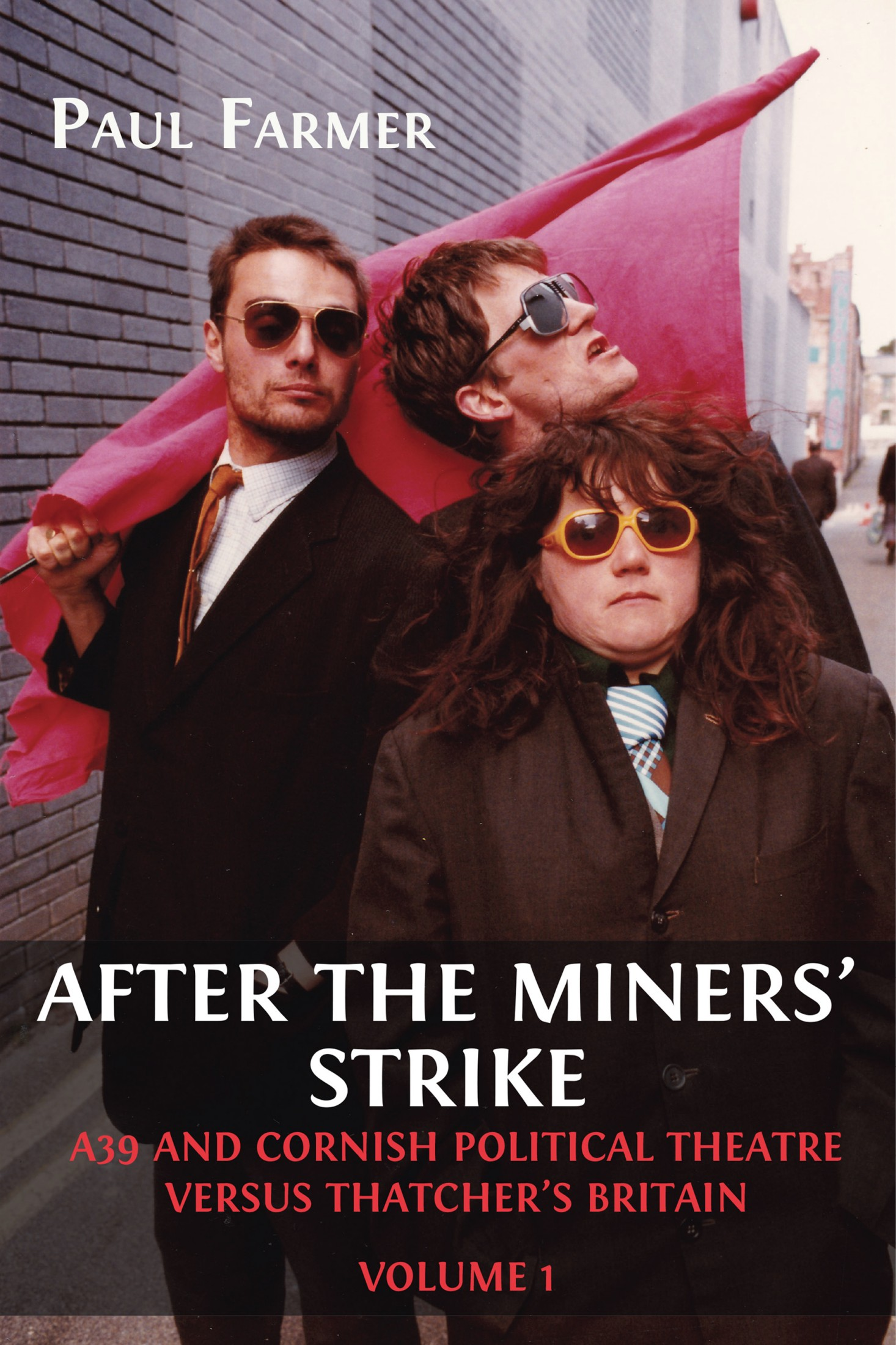

Fig. 26. Trevithick’s Tower, ‘a story coming to tell itself despite them’: Mark Kilburn as Sir John Doddle; Sue Farmer as Lady Julia Doddle; Paul Farmer as the Reverend Green. Photo by George J. Greene (CC BY 4.0).

Fig. 27. Sue Farmer as Lady Julia as the Marauding Nationalist Forces; Mark Kilburn as the Ghost of Don Francisco Uvillé; Groucho Marx as Simon Bolivar. (‘Levels of pretence’ renders it difficult to say who is playing what to whom.) Photo by George J. Greene (CC BY 4.0).

Fig. 28. Sue Farmer as Lady Julia/James Gerard, with Mark Kilburn (wearing Sir John Doddle’s socks) and Paul Farmer as the Montague Twins. Photo by George J. Greene (CC BY 4.0).

Fig. 29. The Trevithick’s Tower panellists meet up with A39’s frequent partners in crime, punk-folk band The Thundering Typhoons, on the Trevithick Day streets of Camborne shortly before the World Premiere. Photo by George J. Greene (CC BY 4.0).

Fig. 30. The Reverend Green, Lady Julia and Sir John with Richard Trevithick himself, sculpted by LS Merrifield (1928), locked in an everlasting gaze up Camborne Hill. Photo by George J. Greene (CC BY 4.0).

1 John McGrath, A Good Night Out—Popular Theatre: Audience, Class and Form (London: Nick Hern Books 1996), pp. 28–29.

2 See editor’s note (p. 42) in Bertolt Brecht, Brecht on Theatre, trans. and ed. by John Willett (London: Methuen 1978) that ‘Gestus’ conveys a sense both of ‘gesture’ and ‘gist’.

3 McGrath, p. 86.

4 See Augusto Boal, The Rainbow of Desire. The Boal Method of Theatre and Therapy (London: Routledge 2003), pp. 16–23.

5 Jerzy Grotowski and Eugenio Barba, Towards a Poor Theatre (London: Eyre Methuen 1976); Peter Brook, The Empty Space (Harmondsworth: Penguin 1972); Brecht & Willett, p. 129.

6 Rick Altman, ‘A Semantic/Syntactic Approach to Film Genre’, Cinema Journal, 23.3 (1984), 6–18.

7 McGrath, p. 83.

8 Bernard Deacon, Andrew George, and Ronald Perry, Cornwall at the Crossroads: Living Communities or Leisure Zone? (Redruth: CoSERG 1988).

9 Arts Council of Great Britain, The Glory of the Garden: The Development of the Arts in England; A Strategy for a Decade (London: Arts Council of Great Britain, 1983).

10 Rania Karoula, ‘From Meyerhold and Blue Blouse to McGrath and 7:84: Political Theatre in Russia and Scotland’, Studies in Scottish Literature, 44.1 (2018), 21–28, https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/ssl/vol44/iss1/4