Two: Mainly Mope

©2024 Franklin Felsenstein, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0334.02

Fig. 7 Photograph of EMF (hand dated May 1939).

Ernst Moritz (Ernest Maurice) Felsenstein Mope

Born Leipzig, 19 June 1899

Died London, 27 June 1973

Ernst Moritz (or Mope as he became known) was to grow up in the socio-cultural milieu of a traditional German-Jewish family. Where the Hirsches represent Jewry at its most assimilated, the Felsenstein family may be seen as a bastion of Orthodoxy.

MOPE

I was born in Leipzig, Germany, the third one of the seven children–five girls and two boys––of Isidor and Helene Felsenstein.

Fig. 8 Postcard-sized photograph of Helene (“Oma Lenchen”) and Isidor Felsenstein (undated but c. 1900).

Fig. 9 Group photograph of children of Helene and Isidor Felsenstein (1917); back row, Adolf, EMF (both in military uniform); middle row, Grete, Alice, Ketty, and Ruth; front row, Hanna.

Here we are standing together outside our home in Leipzig in 1917, a group photo of me and my six siblings. Fourteen years separated the oldest from the youngest. My oldest sister, Ketty (who is second to the right), was born in 1896, my youngest, Hanna (to the front), in 1910. Behind her are twins, Grete and Alice, who were born in 1901, and to the right of our photo is Ruth, who appeared the following year. She is the most intellectual of my sisters. The two young men in the rear are my brother, Adolf, born in 1897, and myself. Both of us appear in military uniform. The picture was taken when my brother and I were each briefly on leave from army service.

Fig. 10 Present-day color photograph of Leibnizstrasse 19, Leipzig (taken from

https://www.architektur-blicklicht.de/artikel/villa-leibnizstrasse-leipzig-zentrum-nordwest-waldstrassenviertel/).

The Felsenstein family home on Leibnizstrasse in central Leipzig, in which the children grew up, was situated within walking distance of their synagogue. Both Isidor and Helene were immersed in the activities of the Jewish community. Their children passed through the Israelitische Kindergarten, of which Helene was on the steering committee. Within the family, there were plenty of joyous celebrations, such as weddings and Bar Mitzvahs, at which the children could get together with their numerous cousins. In a letter to Vera written weeks before the start of the war, the early experience of a religious education still resonated in his mind as he contemplated the Jewish Fast of Av.

MOPE

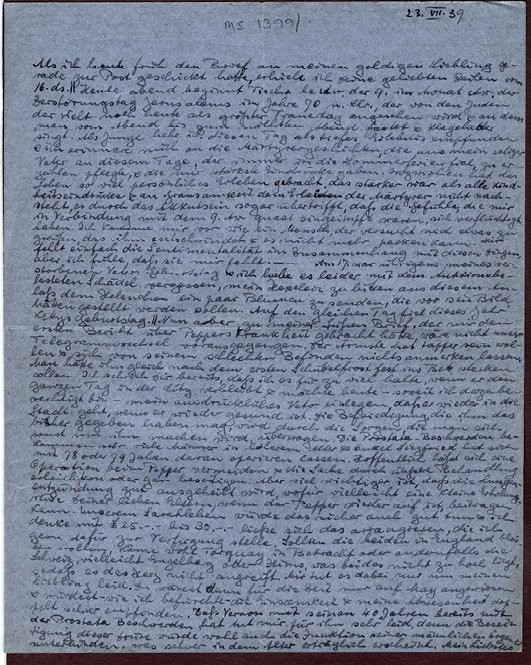

Fig. 11 EMF to VF, 23 July 1939, opening page with reference to Tischa B’Av (Jewish Fast of Av).

This evening, Tischa B’av. begins, the 9th of the month of Av., the day of Jerusalem’s destruction in the year 70 A.D., which is regarded as the greatest day of mourning by Jews around the world, and it is tradition to fast from the evening of the previous day until the following evening and sing elegies. As a boy, I felt this day to be a profound religious experience and I remember the martyr stories that our blessed father would tell us on this day, and those stories made a very strong impression on me.

In the meantime, life has brought so many personal experiences that are much stronger than any childhood impressions, and the cruelty of some of them is close to the suffering of the martyrs, but maybe even exceed them because they are so acute, that the emotions related to this day, with which I was inoculated as a child, have paled. I feel like a human being who is trying to reach for something that is disappearing and cannot catch it anymore.

Though Ernst Moritz’s whole childhood was in an Orthodox Jewish environment, he was to join a non-denominational school for his education.

Fig. 12 Leipzig Schiller-Real-Gymnasium; undated postcard.

MOPE

I was registered at the Schiller-Real-Gymnasium, where the curriculum included the Classics, as well as Math and Science. From early days, I dreamed of a future vocation as a scientist.

At boys’ schools in Germany, as well as academic subjects, much substance was given to sport and physical fitness. My brother Adolf showed his athleticism in field sports, whereas I was less agile on my feet but a strong wrestler.

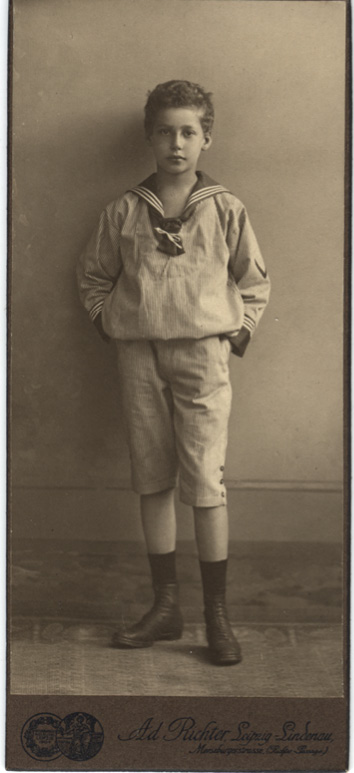

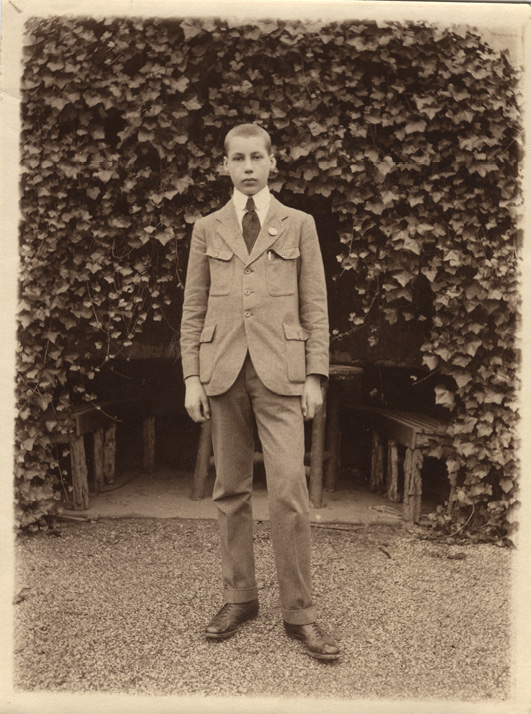

Fig. 13 Studio photograph of EMF as a schoolboy by Adolf Richter… Leipzig Lindenau; undated.

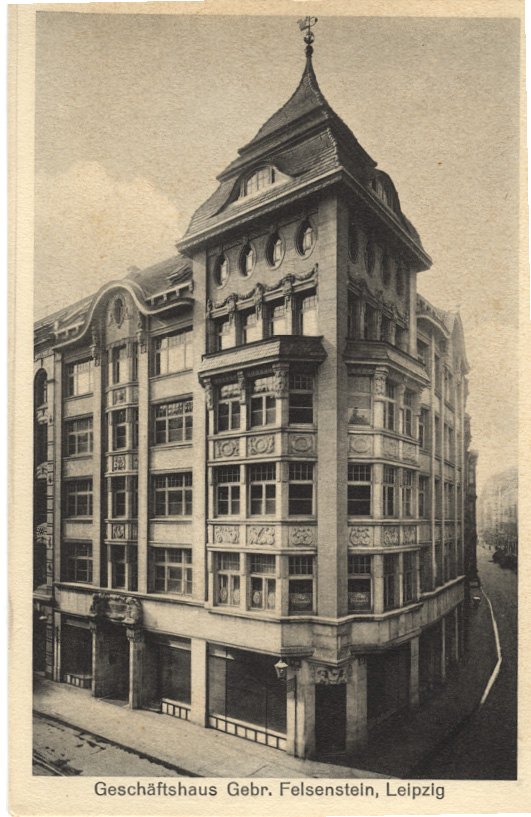

My father, Isidor, is Senior Partner of the Leipzig firm, Gebrüder Felsenstein, a three-century-old fur business. Its showroom is centrally situated on the corner of Nikolaistrasse and the Brühl, a few hundred meters from the city’s main railway station.

Fig. 14 Geschäfsthaus Gebr. Felsenstein, Leipzig [Commercial Building of the Felsenstein Brothers, Leipzig] (postcard).

Through my father’s astute management, the firm evaded the worst consequences of the hyperinflation of 1923. It has expanded into one of the largest fur companies in the city. Two of my father’s brothers share ownership with him, and, to guarantee the future of this family partnership, it is stipulated that each in turn will be expected to place two sons in the business. As head partner, my father put the success of Gebrüder Felsenstein over almost any other consideration, and here we have the crux of the problem that has faced me from early on.

Isidor fathered seven children, but only two were boys, and, in the world of commerce at that time, girls were not in the equation.

Fig. 15 Photograph of EMF as a young teenager.

Ernst Moritz’s Bar Mitzvah took place on 29 June 1912. Two years later, the so-called Great War began. Leipzig was at a distance from the fighting, and, at first, the war had little direct effect on the education of an academically gifted sixteen-year-old. However, by the spring of 1916, most of the personnel at the Gebrüder Felsenstein (including his brother Adolf) had enlisted. Isidor found a partial solution to the shortage of manpower by pulling his younger son out of school to help in the business. There was no consultation, only a paternal diktat that Ernst Moritz must leave school. It was the first of several occasions when father and son were to clash.

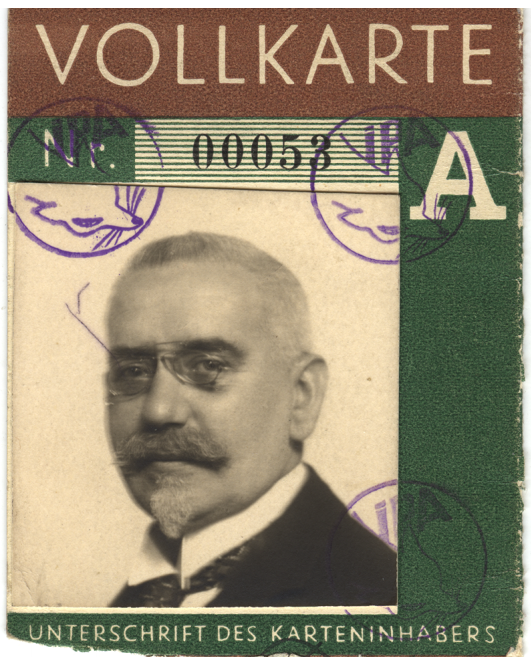

Fig. 16 Photograph of Isidor Felsenstein (1866-1934) on entry pass to International Fur Trade Exhibition.

MOPE

I stood in stark contrast to my father’s opinions. In spite of that I tried, probably much too late, to find my way into the thought processes of my father. I learned to understand that he meant well, only wished the best for me and was convinced that, because he was an older man, he was better able to judge life with all its difficulties, than the young son whose opposition, seen from his point of view, had to be broken.

After an awkward half year working at the Gebrüder Felsenstein, a visit to his grandfather in Königsberg gave Ernst Moritz the opportunity to assert his independence. Still smarting at Isidor’s intransigence, he made the decision to defy Father in favor of Fatherland. He followed his brother by enlisting.

MOPE

In the late fall of 1916, at the age of seventeen, I visited my grandfather in Königsberg and, at that time, took the opportunity to voluntarily register for military service with the Sixteenth Artillery Regiment at Rothenstein near Königsberg. In the spring of 1917, I was sent to France and participated in the war until October 1918.

Ernst Moritz left no written account of his participation in the war, and, in common with many other soldiers, found it challenging to talk about the hellish experience that he underwent. Its post-traumatic effect may account for his arbitrary shortness of temper and fits of anger, which, from early on in their courtship, Vera learned to control and to calm. In conversation with me long after he was no longer there, she would describe him as having had all the passion of a noble stallion, needing a steady rein and a long leash to bring out the best in him.

From stray comments in his later correspondence with Vera (as in one of his letters to her from Leipzig penned during a rainstorm in 1936) we can sense that the echoes of war still jangled in his head.

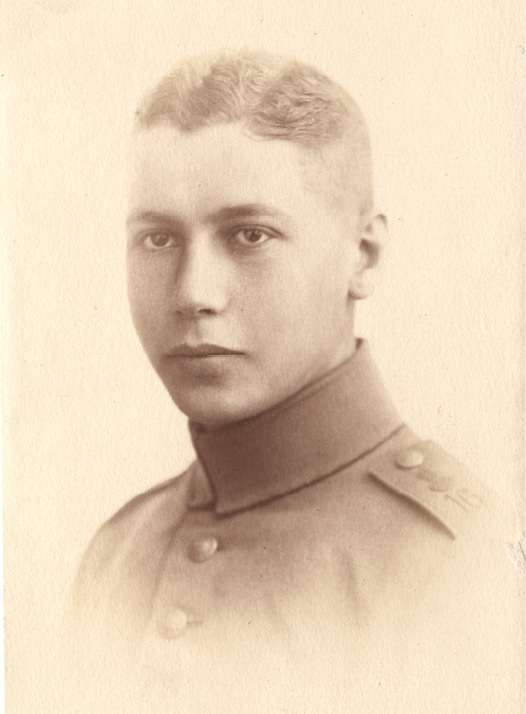

Fig. 17 EMF in German army uniform.

MOPE

There was a thunderstorm this evening. The thunder crashed like striking grenades, without rolling and without dying away. Malignant thunder, imitating the noises of war and recalling memories with their strikes that would better be forgotten. It was pouring down in streams and still did not give any release from the tension.

For all his understandable reticence to revisit the horror that he had lived through, my father did engage with me in several conversations about that period of his life. He told me that, as an observant Orthodox Jew, living conditions in the trenches were even more unbearable than for other soldiers. The food that was issued to the troops was inadequate, and, if meat was available, it was invariably pork. Some cold-hearted German soldiers who fought alongside him would taunt him with slabs of bacon and bratwurst, which they would flaunt before his eyes and, with guttural laughter, tempt him to consume. “Komm Jude, Essen.” Through all this, Mope adhered to his dietary observance. The single consumable that was available in the trenches was tobacco. He became a compulsive smoker, a habit that he was unable to give up in later years. When he died in June 1973, more than a half century after the end of hostilities, it was as a result of lung cancer, a belated victim of the Great War.

The entry of the United States into the final phases of the war coincided with Mope’s deployment to northern France. During the months that followed, German forces fell under increasing pressure. In an engagement in October 1918, a month prior to the signing of the Armistice, Mope was severely wounded by shrapnel from shell fire. He was carried by stretcher to an army field hospital, where, still conscious, he was informed by the surgeons that they were on the point of amputating one of his legs below the knee. As they said this, he glimpsed across from him a large basin that was brimful of amputated limbs. His reaction was to struggle, and refuse to allow the surgeons to carry out the operation. They answered that the amputation was critical to counteract gangrene. Mope fought back that he would rather die than become an amputee. Unwillingly, they agreed to have him stretchered from the front lines, where he was patched up and placed on a train to carry him back to Leipzig. For the next three days and three nights, he lay semi-comatose on the corridor floor of a moving train.

Reaching Leipzig, he was placed under the care of the best physicians, and began the slow process toward recovery. He had been proven right to refuse amputation in the field, yet he was also incredibly lucky. The surgeons at Leipzig were able to extract shrapnel, but concluded that other minor shards were too deeply embedded and would not impede his ability to walk. For the rest of his life, Mope’s shins bore tiny fragments of shrapnel, though these were not visible to the naked eye and did not affect his mobility.

MOPE

During the war, my brother Adolf served as an officer in the infantry. He had what is called “a good war”, being commended for his courage and leadership skills, and receiving the Iron Cross First Class. My own experience was less exalted. Although a source of some embarrassment to me in later years, since I was to receive a service decoration from the British army at the end of the Second World War, I was awarded an Iron Cross Second Class as a recompense for my combat wounds. At my discharge, I was released with the rank of Vizewachtmeister (lit. “Vice–or Sub-Sergeant-Major”), and personally elected to waive my injury pension rights in favor of needier comrades.

Hitler’s crude assertion, widely promulgated by the Nazis, that the cowardice of the Jews undermined the German war effort in 1914-1918, is belied by the active participation of my father and his brother no less than the sons of countless other patriotic Jewish families.