Six: Of Books and Arts (1):

Max Schwimmer

©2024 Franklin Felsenstein, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0334.06

MOPE

I resumed work at the Gebrüder Felsenstein in Leipzig toward the beginning of 1925, and, after four years during which my relationship with my father has much improved, I have been promoted to salaried partner. I think that my father has begun to appreciate whatever small talents I may possess, so long as they are directed to the fur trade. My aspiration to be a scientist means nothing to him, although my entrapment in a career I had not sought will always rankle with me.

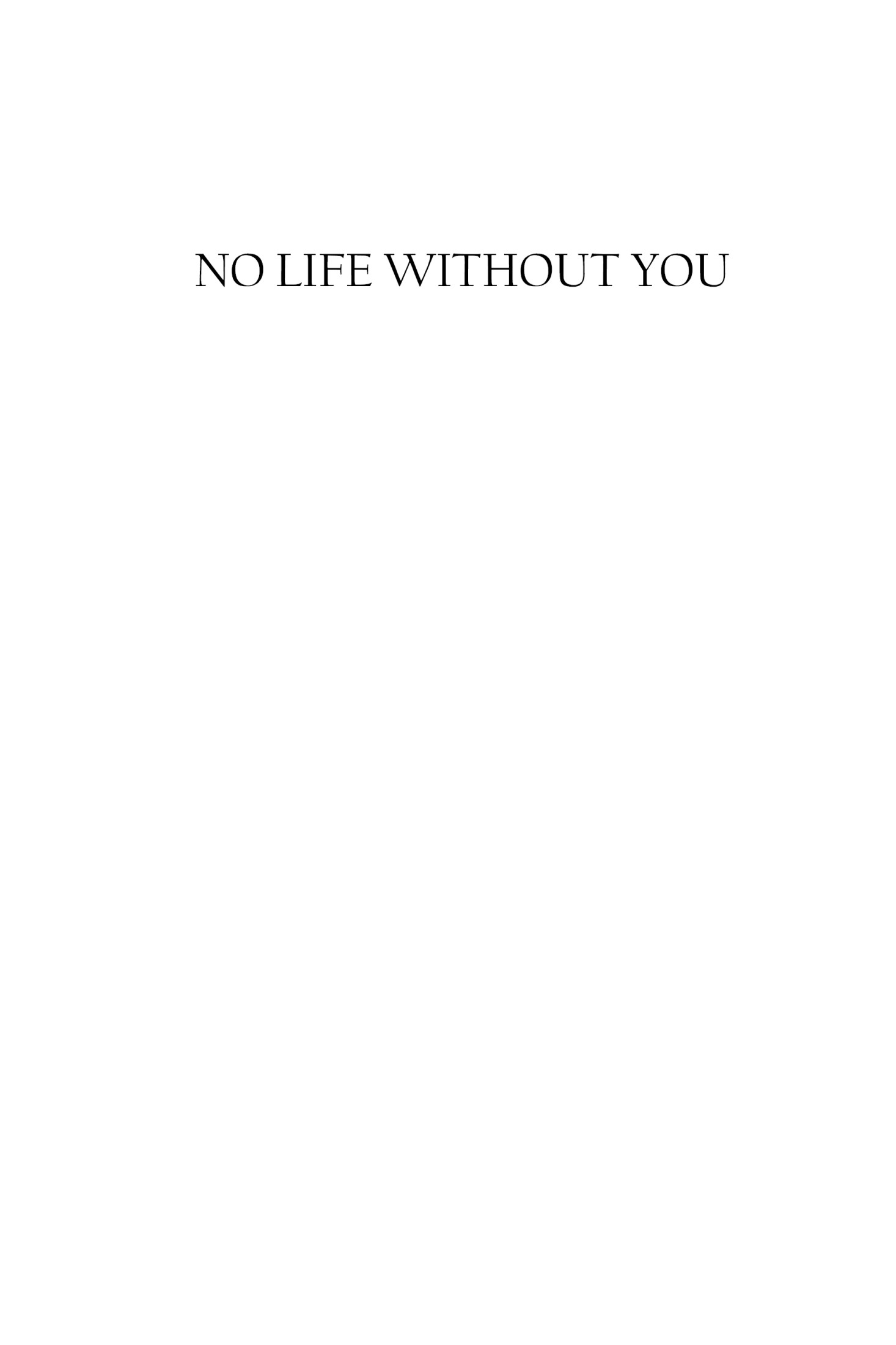

I am sufficiently paid to have been able to move into a spacious three-room apartment on the Kaiserin Augusta Strasse. From there, I can indulge in the artistic and cultural life of the city. The most notable feature of the apartment is my library, which still reflects my former scientific pursuits, but also includes a wide-ranging collection of rare books, Judaica, and German Literature.

Fig. 26 Mope in his study; undated but early 1930s.

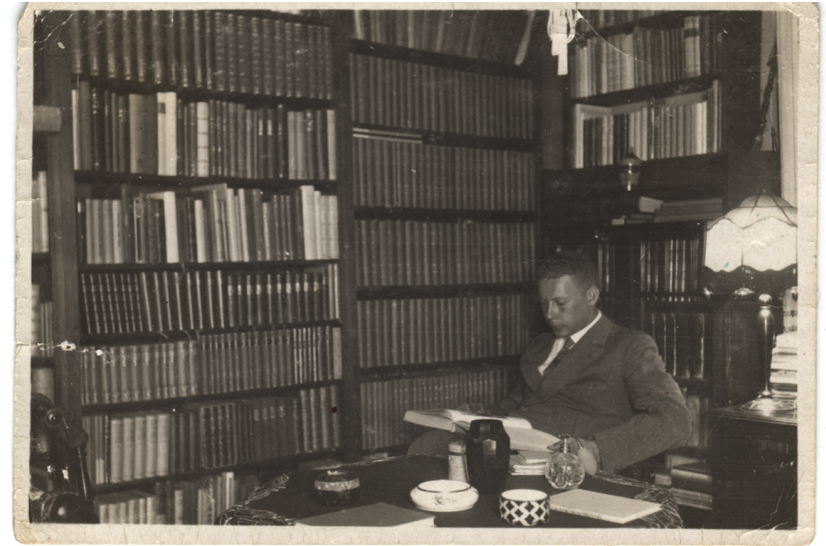

I have commissioned my closest friend, the artist Max Schwimmer, to design for my library a personal bookplate that will accent a Jewish theme. Schwimmer is not Jewish, and has struggled to fulfill my commission. I have other works by him, including several portraits for which I sat, though I keep these loose and unframed as they seem to me to be works in progress. To be absolutely honest, I do not find them to be particularly flattering. For all that, Schwimmer’s wit, intelligence, and sheer talent make him excellent company. We often meet for a conversational smoke at the Café Merkur on the Thomasring or at his studio which attracts many fellow artists and bohemians. Both in his art and in his conversation, Schwimmer is caustic in his dismissal of the opposition Fascist mobs whom he portrays as monsters. Their stridency pushes him to the Communist left. It is a different extreme to the Nazis and not one that I could ever espouse. However, our friendship transcends politics, and I am quite certain that Schwimmer feels the same way.

Fig. 27 Anti-Nazi campaign poster by Max Schwimmer, 1924. “Wählt die VSPD–Vote for the V.S.P.D. [Independent Social Democratic Party]. Reproduced in Hellmut Radmacher, Masters of German Poster Art (New York: The Citadel Press, 1966, 101) and other sources.

I have often wondered–and continue to wonder–what happened to Mope’s library and his other belongings. He would often talk nostalgically about the books and works of art that he had had to leave behind in Leipzig. None of these were ever recovered.

What evidence is there today? Little survives to give a sense of the composition of Mope’s bachelor apartment. During the 1930s under Hitler, its contents were transferred more than once to other premises before they were impounded. Some post-war correspondence with family acquaintances in Leipzig who tried unsuccessfully on his behalf to reclaim Mope’s valuables, provides a basic list of an impressive apartment. Its contents included fine furniture and fixtures, a set of white Rosenthal porcelain, an Indian tea service and a similar coffee service, a silver case, miscellaneous glassware and lamps, a painting by a Dutch old master, and a bronze Buddha. Shortly after they took power, the Aryanization laws mandated by the Nazis drove him to move more than once into smaller and less secure accommodation in areas of the town where Jews were still permitted to live. His library and papers were put into storage in one of the company warehouses. The size of his collection forced him into weeding out.

MOPE

Yesterday and today, I sorted all of my old correspondence, photographs and books. Among the photographs, there were a lot of pictures of me, most of which I had completely forgotten about. Unfortunately, I did not reduce my library nearly as much as necessary. If I took out 150 books (I did not count them), that number would not be too low, and I had counted on three or five times that many. It is so difficult to part with these friends who only talk when they are asked and never say more than is contained within them, if imagination is not involved.

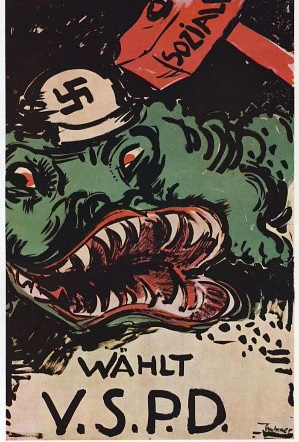

Among Mope’s books left in Leipzig were a number that were illustrated and inscribed to him by Max Schwimmer.1 Mope referred to him, even in later years, as his closest male friend. Schwimmer, who was four years older than Mope, had also been drafted into the army, returning to Leipzig after the war and enrolling at the university where he studied art history and philosophy. In 1926, he was appointed as a drawing master at the Leipzig School of Fine Arts, but was dismissed in May 1933 because of his left-wing political views and his so-called “degenerate art.” The following year, Mope helped fund a joint trip they made to Dalmatia, both very taken by the beauty of Ragusa (Dubrovnik). Here is a handsome photograph of Mope on the ramparts at Dubrovnik that will have been shot by Schwimmer.

Fig. 28 EMF on a rampart in Ragusa [Dubrovnik], June 1934.

Unlike many—or most—Germans, Schwimmer was willing to defy Nazi injunctions against socializing with Jews, and Mope was always a welcome visitor to his studio, visits he savored as a rare escape from the ostracism that he and fellow Jews encountered everywhere else. Later, in 1936 and 1937, he would use his time there to write to Vera, Schwimmer often enhancing the letters he wrote with erotic watercolors.

MOPE

Today is October 23, 1936. I am sitting at Schwimmer’s writing. When I arrived, I apparently interrupted a tender tête-à-tête he was having with his girlfriend. Still, we soon engaged in lively conversation: art, artists, philosophy, with a few bottles of wine. The air of the studio is pregnant with smoke and the new pictures with their colors shine through the haze with great vitality. Two landscapes, in between a flower and fruit still life, decorate the walls. Max really is an exceptionally gifted artist, and it is sad that the time of patronage is over, a time in which he certainly would have had a life free from worry, at least in a material respect, and even more regrettable, given my own reduced financial circumstances, that I cannot be the patron myself.

He now says he wants to draw a sketch at the head of the letter, but I tell him I do have to hurry in order to catch the last train for mailing this letter to you.

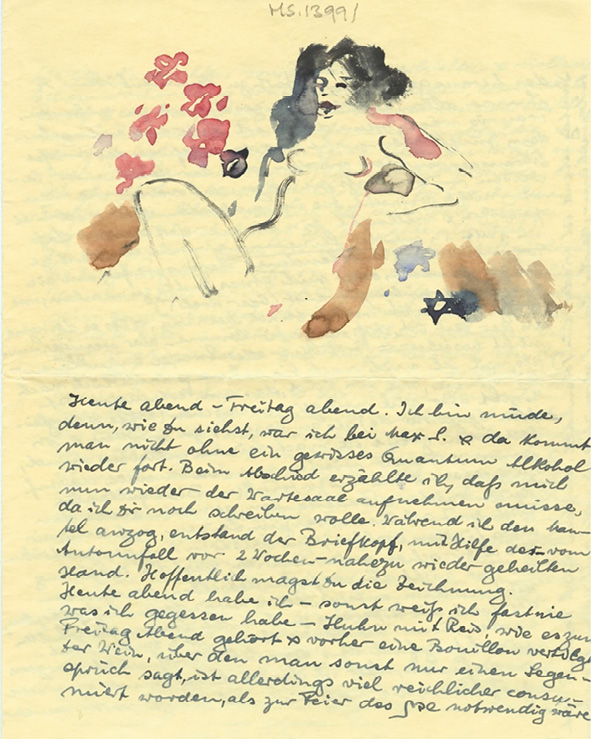

Fig. 29 Erotic watercolor by Max Schwimmer adorning another letter from EMF to VH, Leipzig, 28 November 1936.

When it finally came time to say good-bye, I told him that the station waiting room would have to accommodate me once again, since I still wanted to complete my letter to you. While I was putting on my coat, the letterhead came into being with the help of the hands that are almost completely healed now–after he was injured in a car crash two weeks ago. I hope you like the drawing, and that you will find it as agreeable as I did and not to the shock of my dear mother–who caught sight of it just before I mailed the letter–and says to her way of thinking the sketch is obscene!

Schwimmer’s erotic letterheads adorn a number of Mope’s letters from Leipzig. After receiving one of Schwimmer’s watercolors, Vera cautiously wondered whether they may have been intended by the artist as a friendly payback for the almost unobtainable art supplies that Mope had secured for him when traveling outside the country. Mope rushed to Schwimmer’s defense.

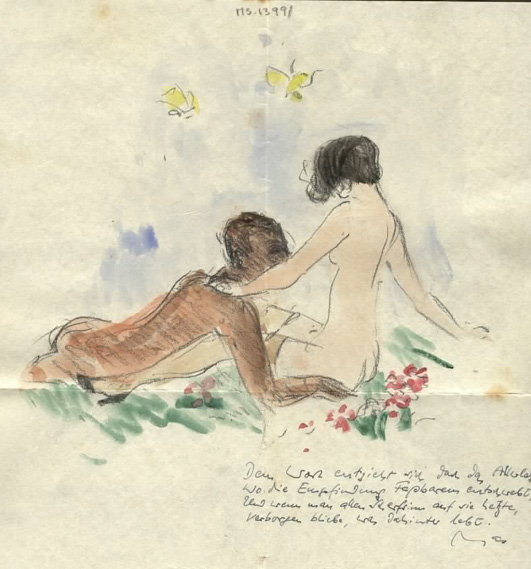

Fig. 30 Erotic watercolor by Max Schwimmer included with a letter from EMF to VH, Leipzig, 20 April 1937.

MOPE

I definitely do not share your opinion about Max’s drawing, because that was not meant to be any kind of “compensation,” but was only meant as an impulsive expression of joy. He acted like a child with those colors and thanked me so ardently for them that the drawing should not be regarded as a receipt. He has often given me drawings, without equivalent, that such a thought would not even enter my mind. He is an artist and should be judged completely differently than average people. Even if I don’t agree with his manner of doing things a lot of times, he is entirely clean this time.

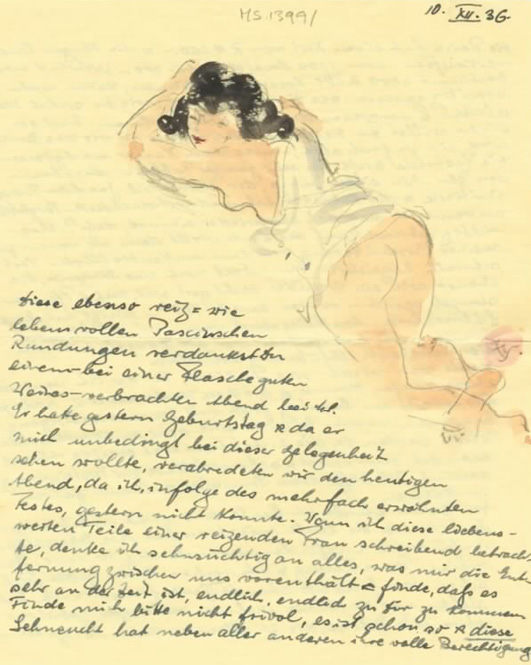

Fig. 31 Erotic watercolor by Max Schwimmer adorning a letter from EMF to VH, Leipzig, 10 December 1936.

You owe these charming as well as lively curves to an evening spent at Max Schwimmer’s–spent with a bottle of good wine. You cannot get away from here without a certain amount of alcohol. It was his birthday yesterday and since he absolutely had to see me at this opportunity, we decided on this evening, since I could not make it yesterday. When I look at those loveable parts of a charming woman while I am writing I longingly think of everything that the distance between us deprives me of and I think that it is time, finally, to come to you. Max is now lying supine on his chaise lounge and is trying out the sharpness of his saw and I am sure that he will manage to saw down a tree anytime now with his snoring!

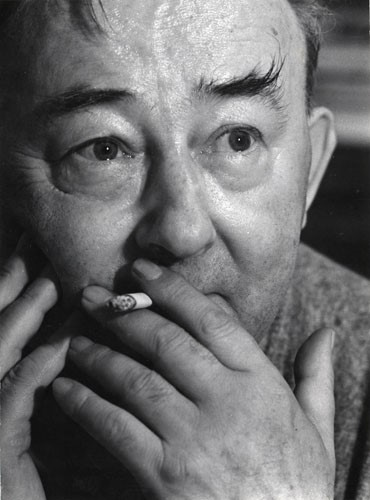

Mope’s friendship with Schwimmer reflects his immersion in the artistic and cultural life of Leipzig that became increasingly regimented after 1933. As for Schwimmer himself, he was called up during the Second World War, serving as a medical orderly. Immediately after the war, he was reinstated to his professorship as head of the graphics department in the now socialist Democratic Republic of Germany (DDR), where he was given many accolades, but because of the political divisions of the Cold War, he remained, at least until recently, almost unknown in the West. He and Mope resumed contact by mail over many years but had to wait until 1958 before they met again in London where Schwimmer was sent to represent his country at an exhibition of East German Graphic Art and Sculpture.

Fig. 32 Later photograph of Max Schwimmer, 1950s (taken from Inge Stuhr at https://www.lehmstedt.de/schwimmer_bio.htm).

Schwimmer claimed that the primary reason for coming to England was to reconnect with Mope. Their reunion was joyful. However, when it came to politics, although retaining much of his natural idealism, it was evident that he had become more and more disillusioned with Communism. He died in his native Leipzig two years later.

1 A photographic portrait of the artist Max Schwimmer (1895-1960) is available in the online resources to this book, https://doi.org/10.11647/