Eight: “I Will Give Up Medicine!!!!!”

©2024 Franklin Felsenstein, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0334.08

Fig. 35 Photograph of VH, rubber dated on verso as 23 July 1938 (likely a copy of an earlier shot from c. 1930).

POLITICAL TIMELINE JANUARY–MARCH 1933

- 30 January 1933: President von Hindenberg appoints Adolf Hitler Chancellor of Germany

- 27 February 1933: The Reichstag is set ablaze. The fire is blamed on the Communists.

- 28 February 1933: Presidential decree giving Chancellor Hitler emergency powers. All one hundred Communist Members of the Reichstag arrested.

- Franklin Delano Roosevelt becomes Thirty-Second President of the United States.

- 9-19 March 1933: Riots against German Jews promoted by the SA, so-called Storm Troopers of the Nazi Party.

- 22 March 1933: First concentration camp–Dachau–set up. By 1945, there were over 1,000 camps.

- 23 March 1933: Ermächtigungsgesetz (Enabling Act), passed by the Reichstag, gives Hitler’s government dictatorial powers. Hitler promises that Germany’s growth will be fueled by ‘blood and race.’

At the end of January 1933, President Paul von Hindenburg appointed Adolf Hitler as Chancellor of Germany. Less than a month after the German Parliament–the Reichstag–was set ablaze, likely a deliberate act by the Nazis, providing the pretext to round up and arrest Communists and other dissidents whom they blamed for the fire.

Fig. 36 The burning of the Reichstag, Berlin, 27 February 1933; National Archives, Washington, D.C. (ARC Identifier: 535790).

Anti-Semitism was rife. With bewildering speed, a host of new laws were introduced and actions taken that attacked the very presence of the Jews in Germany. In Hitler’s warped view, as expounded in his autobiographical manifesto Mein Kampf (1925), the Jews’ agenda was to “enslave” the Germans, and, for him, the only way to block that was to root them out. Once in power, he wasted no time pursuing his hate-filled agenda. The Jewish population in Germany in 1933 was approximately half a million out of a population of sixty-seven million, thus representing less than 0.75% of the whole.

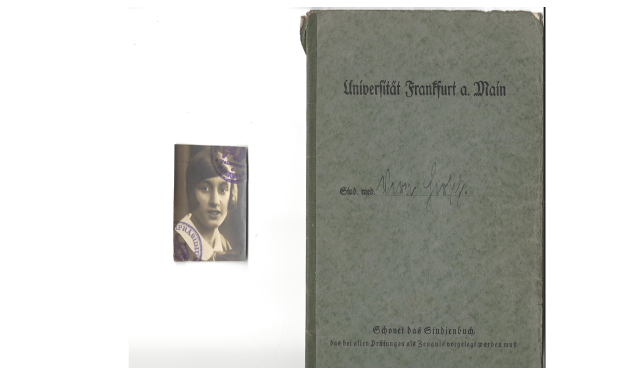

How did his agenda of terror affect Vera? Her surviving “Studienbuch” shows that she had enrolled at the university on 1 May 1929, proceeding over the next four years to pass all the requisite classes in such subjects as anatomy, physiology, pathology, clinical medicine, etc., but that she withdrew quite abruptly before the beginning of the summer semester of 1933, a few months after Hitler had come to power.

Fig. 37 Cover of “Studienbuch” of VH, containing her transcript and photograph.

On 1 April 1933, the new German government conducted its first nationwide boycott of Jewish businesses. “All across the country,” summarizes The Holocaust Chronicle, “Nazi Storm Troopers and SS men posted signs that advised ‘Don’t Buy from Jews’ and ‘The Jews Are Our Misfortune.’ They smeared the word Jude (Jew) and painted the six-pointed Star of David in yellow and black across thousands of doors and windows. They stood menacingly in front of the homes of Jewish lawyers and doctors as well as at the entrances of Jewish-owned businesses. Germans were ‘encouraged’ not to enter, while Jews were arrested, beaten, harassed, and humiliated.”

Frankfurt University was a prime target for the newly empowered fascists. On the day of the boycott, its main building was taken over by eighty thugs in SA uniform, who enforced the prohibition by preventing Jewish students from entry. According to Peter Drucker, later a path-breaking management guru but then a novice teacher in the law faculty, Frankfurt had enjoyed a reputation as “the most self-confidently liberal of major German universities,” and the Nazis calculated that subjugation of its faculty, which included many distinguished scientists, “would mean control of German academia altogether.” Drucker had been present at a faculty meeting a few days before when, amid promises to expand funding for “racially pure science,” the new Nazi commissar for Frankfurt “launched into a tirade of [anti-Semitic] abuse, filth, and four-letter words such as had rarely been heard even in the barracks and never before in academia.” The fallout of this was a shameful abjuration whereby most of the Aryan professors now shunned their Jewish colleagues, keeping “a safe distance from these men who, only a few hours earlier, had been their close friends.” Jewish members of faculty were henceforth forbidden from entering the university and were shortly after sacked without pay. Drucker hastily exiled himself from Germany.

In common with many others, Vera recalled 1 April as the initiation of the systematic victimization of the Jews by the Nazis. Her journal entries capture well the trauma of the moment as she wrestled with how to come to terms with an insufferable situation. Like many Jews in her situation, she began by being full of self-reproach in trying to account for the political change.

Fig. 38 Boycott of Jewish Businesses, Hamburg, Germany, 1 April 1933; https://www.dhm.de/archiv/ausstellungen/holocaust/r2/2.htm.

VERA

5 February 1933

Today, I want to put down my current views of life once again, because it is more than likely, with my good memory, that I will no longer remember anything about this time.

On Thursday, 2 February, three days after Hitler was made Chancellor, Hellmuth Winkler, a boorish medical student who prided himself on his Aryan extraction, did me a great service without knowing it. He and I were discussing the state of affairs of the Jews under the new regime. He maintained that, because of constant misgivings and hesitation and lack of self-confidence, a Jew is not able to accomplish anything.

That really hit me right in the middle. Is that not exactly the way I am? This exaggerated fear is exclusively a Jewish degenerative aspect. Despite our differences, I think that I have discovered a human being in Winkler. I found that even now there are young and pleasant people, well-educated, with good manners and with similar problems. This affirmed to me once again that decency of manners can protect from anti-Semitism, under certain circumstances.

It came as a profound shock to Vera that Winkler’s seemingly sincere profession of friendship, to which she was initially attracted, was no more than a failed attempt to seduce her.

VERA

1 March

Something I have not mentioned so far is my disgusting brush with Winkler. For him to go so far and engage in that kind of thing without even feeling some kind of attachment is a stupid thing to do, and any kind of punishment I might have had to face would serve me right.

Once again–as with Heising before–Vera came face to face with the Nazi barriers between Jew and gentile. It remained still unclear whether she would be able to complete her final year as a medical student.

VERA

Uncertainty! Where should I do my clinical training? Probably in surgery, at least for part of the time, but where?? Where should I have them give me work as a doctor? What will become of me? Am I even able, with that small brain of mine, to finish this course of studies? Uncertainty is always something horrible.

Things seemed to go Vera’s way when she was assigned for her clinical rotation to the public ward at the Krankenhaus Sachsenhausen, a prominent private hospital in Frankfurt. However, as a Jew, she was not permitted to practice her skills in the private ward.

Fig. 39 Krankenhaus Sachsenhausen, Frankfurt (https://www.krankenhaus-sachsenhausen.de/geschichte/).

When she approached a patient on the public ward to ask her how she was doing, the response was a vicious tirade accusing her of being “an impertinent Jewish woman” who had overstepped herself. The patient called for the Nazi doctor in charge of the ward, who, after listening to her complaint, turned to Vera and pointed her out of the hospital. Her shock at this is captured through her journal in her frightened and self-critical ruminations.

VERA

23 March

So, I was thrown out, accused of having bad manners. Entered my clinical rotation three weeks ago. Surgery in the private hospital Sachshenhausen. Because I was assigned to the 2nd class patients and actually asked a patient how she is.

Maybe I am really lacking an understanding of the discipline of medicine and all that has been taught to me, and I am actually just an impertinent Jewish woman. Can that be true???

I am sure it was right that the doctor was mad if his patient actually complained to him, but to scold me in that manner and treat me like a criminal was completely unjustified, that is, the man does not even know me and might have been thinking that he was dealing with a pert and ill-mannered person.

What can I say to justify myself? I simply did not know what to do.

I had no idea why he talked that way about the outrageousness I had committed. When I approached the patient, did I feel I was doing something I should not be doing? If I had actually done that, I would have known right away what a horrible misdeed I was committing.

Ugh, for the first time, I feel for myself what it means to be treated as an outcast.

3 April

Sometimes, you think that it can simply not be true. You read about the persecution of Jews in history books.

Because you are a Jew, you get thrown out of your profession, judged, scorned, and you are worthless, powerless.

I wonder what tomorrow will bring. If I could go to England–I have a decision to make, and it will not be easy for me to burn the bridges behind me. It would be best to go to a tropical country with Alicechen and Pepper–preferably not Palestine, because the pure-breed requirements of a Jewish state there are stranger to me than the one being aspired to here. Although it might actually be preferable to being scorned here!…

I wonder if I will ever finish my medical studies.

With under a year before qualification as a doctor, Vera faced a most difficult dilemma. Should she stick it out in Frankfurt with the prospect that she might still be able to graduate? Should she believe, like so many German Jews, that it would not be long before the Nazis would be ousted, and that one should therefore put up with their temporary nastiness? Or did she need to act now, leave Germany, and seek a new life elsewhere? With all these agonizing questions constantly before her, she sought some clarity by putting pen to paper. A long entry, dated 19 April 1933, addressed to herself in her private journal, lists some of the options that, as a self-declared disbelieving Jew, she saw before her:

VERA

19 April

You have to deal with this problem of being Jewish. There are three possibilities:

- Stay here, that is, if you are still admitted to the university, you might be able to continue your studies, although you will always be regarded as second class, and will be treated as someone who is different. Another possibility: in the most advantageous case, you might find work at the Jewish hospital here or start a practice that might just support you, although that is highly unlikely. As an advantage: you know the language, the books…???

- Go abroad. Maybe, if the financial means allow, continue your studies and then practice there, in the best, best case possible, but that is probably not feasible, because it would not be manageable financially––if not for that, I would not hesitate at all, I would leave with joy in my heart, because I have always liked change. That is, if there is any kind of possibility for me to go abroad and find some kind of work, maybe as a domestic worker, a nanny, cook, chamber maid, etc. Something new and different, maybe even appealing in its own way!!!!!

- Which brings me to the third possibility: Go to Palestine. That would mean giving up all the indulgences you have always taken for granted, like a bath, central heating, and a few other purely superficial things. No, giving up those things is not what bothers me, because no one can take away the things I really consider valuable. Wherever I will go, I will try to make a pleasant home for my family, a beautiful one, as far as my finances will allow––it will be my greatest and dearest duty, no matter where I am and what I do. The thing I do not find pleasing me about this is: I would have to adopt Jewish traditions and customs, things whose value and sense I do not accept. There is only one thing that seems valuable to me: to be a decent person, always striving!!! Even today, I still hold the unshakable belief that you can always accomplish anything with that and will do so.

Yes, I think I have made a decision, even if I will be cast out from every country again and again, driven out more forcefully the more I try to assimilate–and that is a danger that exists for anyone in this day and age. Nevertheless, my view of the world tells me that it is the right thing to move to another country in which the Jewish question is not the most burning topic and to start over again there. Maybe that is very superficial thinking, but I consider my time better used for work, instead of mulling over what cuts of meat you are allowed to eat and what you cannot. I am sure that is unforgivably arrogant and frivolous on my part. Nevertheless, that is my true attitude towards such things, exactly what I think, without any feeling of shame. I am sure this way of thinking was created by my upbringing.

However, I think the time for us to argue about religious beliefs is over and also the question of heredity, and if those arguments rise up again anyway, I should leave the country and go to another one where these problems are not problems and where one can use one’s strength for more pleasant endeavors: to be human!!!!!

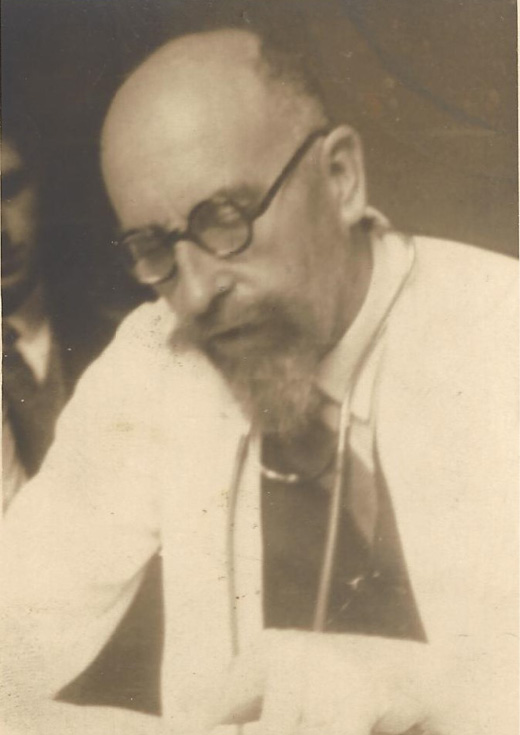

At the medical school, she consulted an eminent teacher of hers, Dr. Franz Volhard, who was sympathetic to her situation. He advised her to petition to stay on but also undertook to write on her behalf should she seek to transfer to an equivalent program in England where he had academic contacts. Volhard was a celebrated cardiologist and nephrologist, whose anti-Nazi stance and support for his Jewish students and colleagues, led to his being stripped of his professorship in 1938, though later reinstated to his former position after the end of the war.

Fig. 40 Photograph of Dr. Franz Volhard (1872-1950), inscribed by Vera, Summer Semester 1932.2

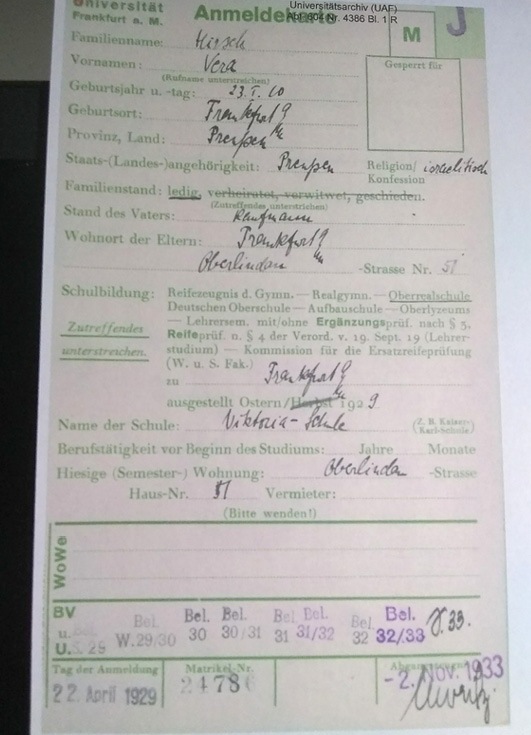

On Professor Volhard’s advice, she applied to the university for permission to pause her studies following the completion of her ninth semester. The documents detailing this are preserved in the university archives where they were laid open to me in 2017. They include a questionnaire, dated 4 May 1933, in which she was obliged to state that neither her parents nor her grandparents were of the Aryan race though the family had lived in Germany for hundreds of years, and that they had never attempted to convert from Judaism. It also asked whether her father had fought for Germany in the First World War (which she answered that he had, even including his regimental details), and if she herself was a member of a political party, to which she answered with an unambiguous “Nein.”

Fig. 41 Nazi Registration Card (“Anmeldekarte”) obliging VH to reveal her identity as a Jew, dated 4 May 1933 (Archives of the University of Frankfurt).

This extraordinary batch of papers brought home to me the abruptness of the trauma of my mother’s departure from her natal city and from the medical ambitions that, until the advent of the Nazi dictatorship less than one hundred days before, had determined the course of her young life. Ultimately, there was only one person whom Vera trusted unreservedly to help her to resolve the painful questions that confronted her. My grandmother–Alice––was adamant that her daughter must suspend her studies and leave for England. From their first conversation, she took it upon herself to spell out to her daughter how dangerous the situation was and to share her visceral sense that it could only get much worse. Alice employed an intermediary, Anna Schwab, to put her in touch with Otto Schiff, the founder of the Jewish Refugees Committee in London.

VERA

26 April

There will never be another human being like my Mutti! As soon as things started happening, on 1 April, she wrote letters explaining my situation to all the people that she knows in London. Although she does not want to be without me for so much as an hour–this self-sacrificing love, action, and flexibility is simply unmatched.

A few days later, Mutti arranged a meeting with Mrs. Schwab who was visiting [Frankfurt] from London at the Hotel Excelsior, and she had all the information Mr. Schiff thought I should have.

Following the interview, Mutti and I left the hotel just to come back again and ask her if there was a possibility of an unrestricted residence permit, because I would really hate to give up my studies. I told her that I thought and hoped that I would be able to achieve my goals anywhere as long as I was willing to work hard.

Otto Schiff had grown up in Frankfurt where he was an exact contemporary and erstwhile friend of my grandmother, both of them born in 1873. They may even have been distantly related and perhaps also knew each other from their school days. As soon as he learned that the daughter of Alice Hirsch, née Ettlinger, was coming to London, he reached out and invited her to be his house guest.

VERA

6 May

Tomorrow, I am leaving for London. I have been wanting to write in here for the last few days, but things happened so fast that I simply could not find the time.

Thursday at Volhard’s: he advised me to stay and submit the petition to intercalate. I did that, but I will leave anyway. I will not have any chances here as a doctor to pass the German final exam, which seems so far away to me, but I still wonder if I’m doing the right thing.

2 Another photograph of Dr Franz Volhard is available in the online resources for this book, https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0334#resources