1. Feeling One’s Way Through the Book

© 2023 Kathryn M. Rudy, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0337.01

Anyone who has examined considerable numbers of medieval European books—in museums, libraries’ special collections, archives, and in the homes of private collectors—will have noticed that they rarely survive into the modern era unscathed. Candle wax, water, and fire can disfigure books dramatically. Repeated handling can result in more subtle damage to images, parchment or paper folios, stitching, or bindings; this includes applying grease or dirt through bodily contact, abrading material by repeatedly touching it, poking holes by sewing on objects, and degrading the fibers of parchment, paper, leather, and thread by repeatedly bending and unbending them. These activities leave traces that reveal how people have interacted with books. Heavy use is visible in dirty surfaces, tattered stitching, frayed edges, and deformed material.

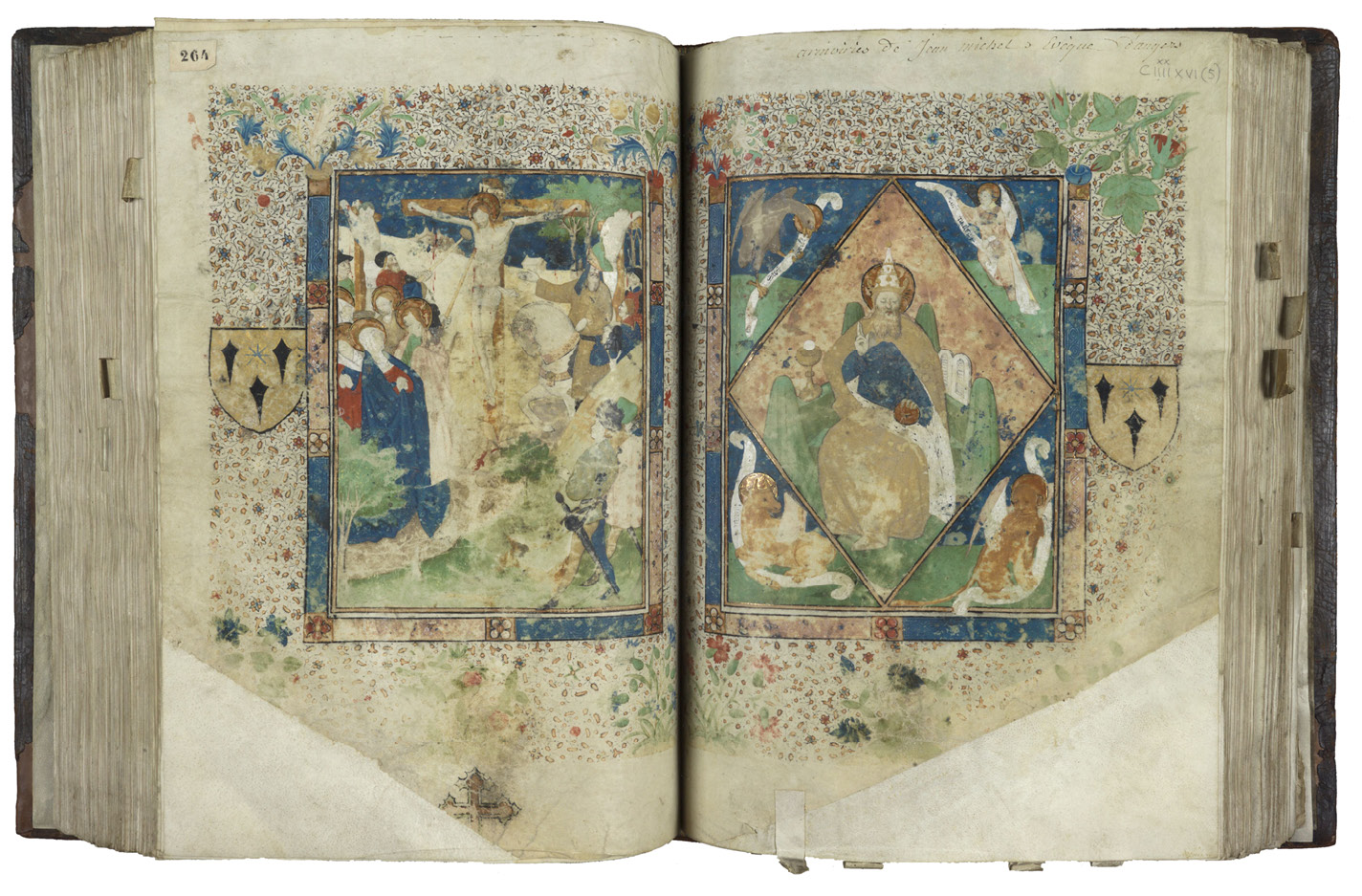

Consider an opening from a missal made in Angers (Fig. 1).1 The imagery in the spread has become murky and mottled, stained and smeared, especially at the center of each of the framed illuminations, with Christ’s legs dissolving into the wooden vertical of the cross, John’s robe blending into the featureless topography, and Christ’s loved ones rendered faceless. The lower corners of both folios were so sullied and damaged that a modern restorer replaced them with crisp white parchment. This manuscript was probably made for Jean Michel’s investiture as Bishop of Angers in 1439. The bishop’s coat of arms, featuring three large nails, flanks the images in the opening. The decoration testifies to a bespoke and precious manuscript, while the abrasion testifies to something utilitarian and work-a-day.

Fig. 1 Opening from a Missal for the Use of Angers at the Canon, 1439? Angers, Archives départementales de Maine-et-Loire, J(001) 4138, fol. 196v (quater)-196r (quinquies). Cliché: IRHT-CNRS

Although the Angers Missal has been exhibited internationally,2 curators often exclude damaged manuscripts from exhibitions, and cataloguers rarely describe this damage or illustrate it in plates. Institutions regularly digitize only the “museum-quality” manuscripts and miniatures in their collections, leaving the others to languish in obscurity; the importance of these institutional decisions cannot be underestimated, as increasingly, scholars’ access to medieval manuscripts is mediated through digital proxies.3 At the pre-publication layout stage, scholarly authors banish images of tattered manuscripts from books and articles, and editors have been known to crop out damaged edges in documentary photographs. Yet these signs of wear reveal much about how people interacted with their manuscripts, and as such, they hold a rich record of a book’s past. Noticing, categorizing, and studying these forms of damage are the subjects of this multi-volume book.

Although one could approach these questions from the perspective of a conservator who is responsible for stabilizing books, or a restorer seeking to reverse signs of wear, I am approaching the matter from the perspective of an art historian who asks: Why does the image look the way it does? In considering the image in its material context, I also ask: Why do the page and the volume look the way they do? I am observing and analyzing, not intervening. As part of a future project, I will use laboratory equipment that extends human vision and applies metrics, but for the present preliminary study, I rely solely on my own (bespectacled) sight, sound, and touch. Although many of the figures in this book present images from manuscripts, I have tried to treat the miniatures in their bookish contexts. It has often been necessary to make or commission new photography in order to capture entire books rather than cropped images within them. I am interested in how people interacted with images, decoration, and text in the past, but those elements are part of a larger context—namely, the manuscript as a whole—and individual manuscripts were involved in a collective response. My interest telescopes from the image to the page, to the book, to its community of users, and finally to the constellation of objects with which it was used. This approach implies that meaning-making takes place as much in the reception as in the production, and that the user or users could co-produce the image. Moreover, the image was not stable, but subject to loss, abrasion, and even repainting.

It is, of course, not possible for one person to systematically examine every damaged manuscript, nor do I pretend to have done so. But I have examined manuscripts for signs of wear for well over a decade. I began identifying manuscripts that had been deliberately touched in 2007, when I gave a public lecture on this topic at the Koninklijke Bibliotheek in The Hague. Since then, I have visited hundreds of repositories of medieval manuscripts and collected hundreds of thousands of digital photographs. More than 900 of the photographs document interpretable marks of wear. From that set, I selected manuscripts that would populate the typology outlined in these pages, without overwhelming readers with redundant examples. Many come from collections in Northern Europe and the UK, where I have spent much of the last 25 years. I intended to demonstrate that such deliberate touching is a pan-European phenomenon, and I hope that further studies by regional specialists can begin to specify distinctive local and chronological nuances.

Some of these ideas first appeared in my Dirty Books project, in which I measured levels of grime in the margins of fifteenth-century prayer books in order to discover which parts of the book had been used and which ignored.4 The current study analyzes different kinds of grime, as well as abrasion, generated from a variety of user activities. Since this book reflects 25 years of research into manuscripts in repositories across Europe, North America, and Europe, it has been necessary for me to select some examples and exclude others. I am also working on projects in other media related to this current body of work. These include a picture book containing many more examples of damage, but with only a thin aspic of text to hold them together. I am also creating a series of videos to capture moving images of manuscripts, which can document some signs of wear more eloquently than still images and printed prose can.

I. Structure of the Book

This is the first of multiple volumes. In Part I of the current volume, I introduce a haptic approach to studying European medieval manuscripts that were made and used between ca. 1100 and ca. 1500. What can signs of wear, in the context of the book’s contents and social function, reveal about how the object was used in rituals? In this first chapter, I provide an overview of the approach, which draws on archeology, anthropology, and linguistics, as well as on studies of memory. I attempt to answer a question frequently asked by audiences when I have discussed this material publicly: How does one know when the damage occurred?

In Chapter 2, I categorize the various kinds of traces visible in manuscripts, which correspond to respective ways of handling those books. This taxonomy, illustrated with examples, operates throughout the rest of the volume and in the future volumes, as well. The subsequent chapters make plain the great variety of meanings, emotions, and rituals involving book-touching. Each of these chapters treats a group of manuscripts used in a particular context, for it was the ritual setting that drove how books were handled.

Chapters 3 and 4 investigate rituals governed by priests and bishops. In the context of official ceremonies, two kinds of manuscripts played central roles during ecclesiastical rituals: Gospel manuscripts and missals. Carrying out codified rituals required touching these books in ostentatious ways. Such rituals were adapted for other contexts, in which oath-taking and official legal and civic pronouncements took place; these will be taken up in Volume 2.

In Chapter 6 I consider rituals other than the Mass that took place in churches, and dwell for some time on one manuscript—the Grand Obituary of Notre-Dame—whose signs of wear reveal the tactile aspects of funerary memorial practices. It is noteworthy here that the manuscript’s wear was caused during memorial services for several celebrated members of the church and each one is different: there was no single ritual but rather the individual obituaries engendered slightly different micro-cultures of book-touching.

Although the subject of this study is ostensibly books, it is really about people, and it will demonstrate how people who had roles as officials (abbots, priests, members of the high nobility) used books in theatrical ways that reinforced their authority.

II. Damage

In proposing that a variety of practices by users caused different kinds of damage to medieval manuscripts, I endeavor in this study to reveal how early owners interacted with their books.5 Such users were not being subversive, but by touching the folios or even specific images, they were using their books in a perfectly sanctioned way. As I hope to show, different gestures of handling the manuscript resulted in patterns of wear distinct enough to be distinguishable: setting a dry finger onto an image and then lifting it will mar the book differently from stroking it; touching with a wet finger will liquefy some of the water-soluble paint in a way that a dry finger will not; touching paint that is adhering to a semi-porous material (such as parchment) yields a different pattern of damage than touching paint on a non-porous material (such as gold leaf) or a highly porous material (such as rag-based paper); touching the book with the mouth and face will deposit facial oil which may affect the translucency of the page, but not reconstitute the water-based paint; and one person touching the book many times will yield a different pattern than many people each touching it once. Throughout this study I will consider signs of wear with respect to these and other variables, further inflected by social contexts.

Because I hold as axiomatic that the parchment surface provides clues as to how people behaved with their books, manuscripts and their signs of wear are my primary evidence, although I occasionally refer to other medieval hand-held objects. Stains, marks, and compounded inadvertent smears of dirt in books reveal important aspects of how they were used, and even what people hoped to gain by using them. How did readers activate their bodies in the ritual of reading? Can a pattern of wear be discerned within a particular book, or across a group of books? Were the marks formed by love? Desire? Hatred? Habit? Were these micro-performances with hands and fingers done publicly or privately? Did books help to achieve group cohesion and identity, and if so, how? What of their hopes and desires are revealed in their habits and rituals?

Previous scholars have discussed beholders’ desires to destroy images—that is, to commit iconoclasm—but they have not paid enough attention to other forms of degradation and the methods by which the surfaces of objects were altered, whether deliberately or inadvertently.6 Likewise, marks made by readers wielding quills–-including annotations, glosses, and reading notes—have been studied,7 but until now, marks made by readers’ hands alone—which can also significantly change the surface of the page—have gone largely uncharted. And yet questions of surface are omnipresent in art history. Ever since Giorgio Vasari (1511–1574), the notion of the communicability of the surface of the object in its own right—through brushstroke and style—is at the center of connoisseurship. On the strength of this we credit works of art to particular artists—attributions that, at times, are worth millions. Why, then, can we not equally consider surface degradation and the stories it can tell us about how objects were used? In so doing, I am still asking: “Why does the image look the way it does?,” an essential question for any art historian, but focusing on function instead of production. The beholder/reader co-produces the image alongside the scribe and illuminator, putting on the “finishing touches,” as it were.

Paradoxically, art historians have usually placed more truth value in texts than in images. For example, an art historian can more confidently attribute an early modern painting when armed with a contract or inventory from a contemporary archive than when looking closely at the painting itself. Whereas archives will divulge occasional documents that confirm interpretations about artistic production, their materials are nearly silent on questions of degradation and abrasion, outside sparse instructions to priests to kiss the book or sprinkle holy water, which may splash on it. Nevertheless, medieval writers occasionally emphasized the utilitarian qualities of the objects around them. That objects were subjected to intense, often ritualized handling in the Middle Ages is confirmed by Boncompagno da Signa (c. 1170–1240) in his book On Memory (Rhetorica novissima).

I claim it as established that all books that have been written, or have existed in every region of the earth, all tools, records, inscriptions on wax tablets, epitaphs, all paintings, images, and sculptures; all crosses, of stone, iron, or wood set up at the intersections of two, three, or four roads, and those fixed on monastic houses, placed on top of churches, of houses of charity and bell towers; pillories, forks, gibbets, iron chains, and swords of justice that are carrid before princes for the sake of instilling fear; eye extractions, mutilations, and various tortures of bandits and forgers; all posts that are set up to mark out boundaries; all bell-peals, the clap of wooden tablets in Greek churches, the calls to prayer from the mosques of the Saracens; the blarings of horns and trumpets; all seals; the various dress and tokens of the religious and the dead; alphabets; the insignia of harbors, boats, travelers’ inns, taverns, fisheries, nets, messengers, and various entertainers; knights’ standards, the insignia of arms, and armed men; Arabic numerals, astrolabes, clocks, and the seal on a papal bull; the marks and points on knucklebones, varieties of colors, memorial knots, supports for the feet, bandages for the fingers, the lead seals in the staves of penitents; the small notches that seneschals, administrators, and stewards make in sticks when they pay out or receive household expenses; the slaps that bishops give to adults during sacramental anointings; the blows given to boys to preserve the events of history in their memories; the nods and signals of lovers; the whispers of thieves; courteous gifts and small presents—all have been devised for the purpose of supporting the weakness of natural memory.8

Most of these noisy actions that Boncompagno so graphically evokes involve enacting rituals with objects, either seldom and ceremonial or mundane and quotidian. These actions form the “intangible cultural heritage” in which memory and values are stored and transmitted, and yet, the instructions for using these objects are rarely written down. This may be because ritualized actions—such as slapping boys, notching sticks, signalling to lovers, and indeed making gestures with the paintings in manuscripts—are largely transmitted through social copying and repetition, and the actions are only written down or codified when they are threatened from the outside (with extinction), as the cultural historian Jan Assmann has convincingly argued.9

It is not possible to rely on historical meta-texts to study degradation. Only occasionally do instructions such as rubrics indicate that a reader must, say, plant a kiss. Instead, I am primarily using visual evidence to support my claims. Throughout my research I have kept an open mind about possible explanations for the patterns of wear in manuscripts; most solutions are unlikely to find corollaries in textual records. For example, I have found no documents that describe medieval users touching their books with a wet finger. To bring the varieties of degradation, and the correlative gestures that caused them, into view, I have laid out various kinds of touching that can be identified in manuscripts and have categorized them below (in Ways of Touching); this forms the basis of the rest of this study. Implicit in my approach is that different kinds of touching cause different kinds of damage. A meta-goal is to produce a taxonomy of the types of damage that result from users handling manuscripts, and to improve our ability to distinguish them. The taxonomy appears as a series of nested and hierarchical categories at the end of this study.

III. A Haptic Approach

Mark-making in manuscripts occurred deliberately when scribes, painters, and illuminators applied words, images, and decoration to the book, but also accidentally when votaries handling their folios inadvertently deposited fingerprints, skin, dirt, spittle, wax, and other detritus. I consider these signs of use as readable, interpretable information that can help to construct object biographies. They record some of the past users’ actions. Whereas most historians use texts as sources for writing history, in this project I follow Gustaaf Renier (1892–1962) in seeking traces of the past in the present.10 Rather than pursue the historian’s texts or the art historian’s images, I place human signs of wear—which form a particular kind of trace—at the center of the study. A user could touch different areas of the same manuscript with a variety of techniques and intentions.

While a single use of an object may forever change it—for example, when red wine spills on a white altar cloth, when the swinging sword of Thomas of Canterbury’s executioner dents the blade and chips the altar, or when a thorn from the Crown of Thorns is snapped off in a gifting ceremony to a dignitary—most of the changes to durable objects are gradual and result from the cumulative effects of ritualized actions. Repeated actions cause wear, and that wear can be interpreted to understand the actions that gave rise to it in the first place.

Signs of wear in medieval objects abound, and they tell much of the story of how use changed those objects. Natural materials from which medieval objects were usually made tend to deteriorate. Unlike our own era’s glass and steel architecture, which does not show signs of wear, pre-modern buildings comprised stone, wood, and brick.11 Anyone who has walked up the marble steps of an old building knows how centuries of footfall erode the stone. Likewise, the cumulative steps of thousands of pilgrims in Canterbury Cathedral wore a trough around what must have been a glistening, ornate shrine to Thomas Becket. After Henry VIII obliterated the shrine, only the trough remained. On a smaller scale, many hand-held objects were made of materials of animal origin (antler, bone, amber, leather, skin, parchment, wool, silk, or even marble, which after all also consists of once-living material); such materials often last a long time, but sooner or later reveal signs of wear.12

This study concerns the physical rituals that users employed with their books, and my methodology is conceptually congruous with my subject. Applying use-wear analysis extends my previous work, in which I used a densitometer to measure fingerprints and wear on individual pages to find out which pages of their prayer books votaries read and looked at, and which they ignored.13 Here I have abandoned numerical values and spreadsheets and use only sight, touch, and hearing to make these observations: a well-worn folio has less elasticity, less “snap” than a fresh one; turning damaged parchment folios sounds different from turning pristine ones. I have not tasted any folios, although late medieval users may have done so.14

Every mark that users left in their books through kiss or touch stemmed from a particular moment when they touched that book. Marking the book and leaving traces also produced a specific sensory experience.15 With reciprocal effects, the act of touching changes not only the object but also the person who touches it, perhaps to fulfill a vow, prayer, oath, or other speech act. Book tactility engaged the pile of velvet, the lumps and knobs of leather glued to the cut edges of book blocks, decorative cut-outs and blind-stamped leather covers, sewn-in badges, and curtains. A book was made richer through such variety of materials. In this study I concentrate on how users handled books, those three-dimensional, multi-faceted objects that usually combined texts and images in a physical structure scaled to the human body. When relevant, other kinds of objects (panel paintings, relics, sculptures) enter my discussion. As bearers of the Word in a culture dominated by Christianity, manuscripts possessed a special charge within late medieval culture. Yet they could not, for the most part, be ensconced in locked chests or fully protected from exposure, because manuscripts only make sense when handled: they must be opened to divulge their surfaces and contents.16 The codex constitutes a haptic medium, like clothing, certain liturgical objects, processional carts, storage boxes, or animated sculptures, whose meaning only comes into being during manipulation.17

A. Methods

Use-wear analysis, which arose from the discipline of archeology, has informed my methods and those of some other art historians.18 For example, Anthony Cutler studied the added sheen and loss of surface detail on Byzantine ivories to discover how they were handled.19 Like parchment, ivory derives from animals and therefore wears down after repeated holding. As Cutler points out, often the lower corners of ivory plaques are shiny and abraded, because the thumbs worked away the surface during repeated acts of holding/beholding. (In the taxonomy discussed below, these are inadvertent signs of wear.) This abrasion reveals something important about how beholders used such ivories: they held and manipulated them as embodied actors. In identifying such abraded ivories, Cutler also underscores the intensity of their use. By extension, such signs of wear point to the necessity of these items in culture—as functional, practical, and vital objects.

Using and keeping old objects in circulation for a long time, and copying them accurately, helped to ensure conservatism in devotional practice. Manuscripts provided anchors for the words uttered in rituals. They tied present performance with the sacred past and maintained continuity. As Paul Connerton shows, the transmission of culture demands rituals, and the carrying out of rituals demands ceremonial objects. Objects themselves provide the best witnesses to the rituals that have been performed on them (if those rituals do not outright destroy them). Likewise, ritual actions preserve collective memory.20 The incorporated (bodily) memory that Connerton posits stands in opposition to inscribed (written) memory, although both come together in the manuscripts I discuss; many of the uses toggle between treating the manuscript as a text- and image-carrier and regarding it as a sacred or charged object.

Most rituals require a place demarcated as special; some demand ritualized words (which, if formal, in a foreign language, or mysterious amplifies their power); some need ritual objects, while others rely on a particular set of codified behaviors. So much the better if the objects are transfigured during these manipulations. For example, through loving actions the supplicant could physically alter the object of desire, which would record the nature of the ritual in the object’s accumulated signs of wear. In this regard, it is useful to consider How to Do Things with Words, in which the philosopher J. L. Austin outlines speech-act theory.21 Instead of insisting that meaning is generated entirely from words’ content, Austin proposes that some kinds of meaning can be generated from the contexts in which words are uttered. Specifically, there are certain kinds of language—speech acts—which perform specialized tasks or meanings by their very utterance. In contrast to most normal declarative sentences, a speech act changes the world in some way: for example, “You are now wife and wife,” “I pardon you,” “This is the body of Christ.” These words, spoken by someone who has the authority to speak them—a justice of the peace, the president of the United States, and an ordained priest, respectively—and possibly accompanied by certain ritual actions (such as signing a marriage certificate, making a public broadcast and filing appropriate paperwork, or raising the Corpus Christi) effect significant changes. Ceremonial language with unconventional or foreign words and antiquated grammar often marks speech acts as distinct from regular speech. In relation to my study, many medieval speech acts required touching books in particular ways in order to achieve a permanent perceived change with legal, religious, or cultural gravitas.

Ways of handling books could be considered a “technique of the body,” a term coined by Marcel Mauss, who recognized that everyday actions such as swimming, walking, and sleeping are always contextualized in social settings.22 Walking through a market will be different from walking down a country lane, and even sleeping (whether on the ground in a circle, or under covers in a bed with a pillow) is not “natural” but learned. Consequently, people from different cultures and backgrounds sleep and walk differently. Social settings can equally affect behavior. I apply this idea to manuscript handling by considering the various sites in which reading takes place with prescribed sets of actions. Various people—bishops, priests, judges, deacons, abbesses, dukes, and lay believers, to name but a few—learned techniques of the body that involved and incorporated books. The handling of books in the late Middle Ages occurred in a range of contextually specific ways, which constitute practices of behaving with a culturally important object (the book), whose techniques originated with persons of authority, and whom others imitated. The contexts of use are therefore paramount: Who handles books, under what conditions, with what solemnity, and yielding what results?

A single parchment book could become part of someone’s daily and habituated devotional activities, and therefore bear signs of daily ritual. Once people started consuming printed books, many owned several rather than one, and their devotional rituals might be spread out among several different volumes. Proportional to the total number of printed books produced, few heavily worn examples have survived. Manuscripts in particular, because of their longevity and singularity, were protagonists and mediators in structures of control. Such structures were enacted through rituals that included a priest celebrating Mass at an altar; a prolector (someone who publicly reads at court, a role that will be explored in Volume 2);23 various lay and religious people swearing an oath; students learning from books in school; lay people using books in church, sometimes under the guidance of a confessor. People learned to use their books by imitating the practices of figures in authority, through events that took place in particular locations—at a church (high altar, side altar, nave, church yard), on a street in the context of a procession, in a place of learning (I hesitate to use the word classroom, an anachronism), in a convent (chapter house, refectory), at court, at the city hall, courthouse, in front of the west portal of a cathedral, or at a shrine or chapel. These settings engendered different kinds of book touching. At each of these locations, a select audience witnessed a figure in authority handling a book, and in each of these settings, I argue, that person dramatized the performance of ritual in ways that left traces in the books they used.

In these spaces of authority, officials intentionally touched the books to teach or present beliefs about the world; viewers then demonstrated participation by following their lead. This was part of enacting a social order, in which the book had meaning in terms of the ways it bound people together around faith, the law, and political systems. Christianity’s rituals relied on the authority of the written word. Books therefore figured prominently in its rituals, both as texts that provided scripts and as props that promoted the idea of the Word as divine logos (John 1:1). Priests, bishops, and other ecclesiastical officials brandished books publicly and in so doing demonstrated how to handle them. Books also took center stage at court, where public readings took place as a form of entertainment. Readers who recited texts put themselves with their props—(illuminated) manuscripts—on display as authorities on book handling. The courthouse provided another locus where the book—with its function to hold laws, records, and oaths in perpetuity—was publicly manipulated in ways meant to underscore the cultural and political weight of a legal written code. Scribes transmitted knowledge through copied texts, just as readers transmitted rituals through copied gestures.24

In some cases, particular gestures were required of the audience, which turned audience members into actors. They performed on a stage that involved persons in authority, particular scripted actions, and ritual objects (including books). An analogous public practice—kissing an icon—structured one way in which Byzantine believers used images, as there was considerable social pressure to take one’s osculation in turn.25 Likewise, certain legal and religious rituals demanded audience participation, such as placing a hand on an image. In many of these situations, the book was not the only ritual object present, but served within a constellation of objects, which might also include an altar, lectern, pax, aspergillum, rod, canopy, bier, crucifix, tympanum depicting the Last Judgment, or indeed, an icon. Marks of wear incurred during devotion—both targeted and inadvertent—can equally be observed in manuscripts used during public rituals. Such marks therefore provide us with insight into the ways that groups used touch ritually as well.

The number of deliberately touched manuscripts is so vast that the phenomenon warrants a social explanation. Certain ways in which books were touched publicly—during a performance or ritual—came to resemble ways in which books were handled privately. I am proposing two main forms of behavioral transmission, horizontal and vertical. My premise is that audiences watched authority figures handling books in public settings (such as Mass, where the priest kissed the book) and then adapted some of those behaviors in the use of their personal books of hours and prayer books. Figures in authority—including teachers, confessors, priests, monks, and civic leaders—presented themselves as models. The wealthy laity, who brought their books to church in the later Middle Ages, also put some of their books to use in public settings. Their performances were on display and copied by others. In short, believers were imitative. While their ultimate exemplar was Jesus, they also imitated saints, priests, and each other.

Horizontally, owners of prayer books across peer groups learned and normalized ways of handling manuscript prayer books and books of hours. The similarities in how particular images are touched, such as coffins at the Mass of the Dead in books of hours, is so systematic as to make it unlikely that individuals simultaneously invented this form of book handling in “private devotional” isolation, but rather that ways of touching manuscripts formed a shared practice which, moreover, helped to establish social bonds. (This idea will be taken up in Volume 3.)

Most of the material under scrutiny comes from the later Middle Ages, until the Protestant Reformation and the printing press changed Christians’ relationship with religious authority and with books. Two kinds of manuscripts—the Gospel manuscript (also known as the evangeliary) and the missal—stand at the heart of this study and therefore form the backbones of Chapters 3 and 4. This is because a sea-change occurred in the twelfth century, when the missal was born out of combined elements from the evangeliary, epistolary, and sacramentary. The missal presented a compendium of all the texts a priest would need to conduct Mass (but without the choral parts, which were copied into separate books for use by the chorus). Simultaneously with these changes, Mass became more theatrical and its associated gestures grew larger. The act that sealed the most important ritual in the Latin church—transubstantiation, the turning of the bread into the flesh of Christ through words (the primary Christian speech act)—became more adamantly punctuated with a gesture: kissing. This gesture came to be copied in all kinds of other rituals and adapted for various contexts. This idea, that rituals and gestures of book handling migrate outward and downward into different social contexts, fuels much of the discussion in the book, as well as the argument in Volume 2.

A working hypothesis drives this study: that contexts of book handling produced different ways of touching manuscripts, which resulted in different forms of wear. Traditionally, much of the damage in books has been ascribed to iconoclasm, but that only accounts for two categories of damage. Specifically, users can destroy an image because they object to all images—that is, to the act of representation itself—or they attack an image because they abhor the subject depicted.26 Iconoclasts in the second category, confronting particular figurative images, often mutilated faces and gouged out eyes: they defaced them. In medieval manuscripts, some hostile attacks left their traces in the form of rubbed devils and smeared baddies, or of images of St Thomas of Canterbury obliterated in the post-Reformation maelstrom.27 My few examples are disproportionate with the immense number of medieval images that have been assaulted in these ways.

Leaving iconoclasm aside, here I examine other behaviors and motivations which left distinctively different patterns of wear. For example, book users expressed extreme veneration of images—what one could call iconophilia—through physical contact: positive emotions accompanied some users’ intensely corporeal relationships with books. Why one touched a book inflected how one touched: with the hand or the mouth; with the whole hand or just a finger; and with a finger that could be wet or dry. One could use a sharp instrument for poking (usually for iconoclasm), or a blade for scraping (possibly in an extreme form of iconophilia). One could gesture lightly or rub up and down vigorously. One person could touch a single image hundreds of times, or hundreds of people could touch an image once, and the resulting patterns of wear will differ. The actors, the type of book, the location, and the users’ emotions all contextualize modes of handling. Different ways of touching medieval manuscripts manifest themselves in visibly distinct forms of wear. I have recorded different forms of wear to avoid labeling all damage as “iconoclasm.”

B. When Did the Damage Occur?

When studying the signs of wear in medieval manuscripts, one persistent question is when the damage occurred. Camille addresses this in an article about erasures of sexualized images in manuscripts, and he concludes that much of this kind of sanitation of manuscripts occurred in the fifteenth century, rather than at the hands of priggish Victorians; he contends that Europeans were developing a sense of privacy in the late fifteenth century that amounted to a form of prudery.28 One rarely has proof, only evidence, of when damage occurred; however, one can consider the following observations, which suggest that use-wear damage was often performed early in the life cycles of manuscripts.

Those who keep their books in pristine states, by definition, leave few traces behind; those who value utility over preservation often find multiple ways to interact physically with a book. One can identify three different categories of user-generated additions. Certain kinds of manuscripts, such as necrological calendars, are designed with plenty of blank space to be filled in with the names of the dead. To fill them up is to use them in the manner intended. Other manuscripts have blank parchment at the ends of quires, of which users took advantage to add texts. Into prayer books and missals, they could inscribe more prayers or new Masses onto flyleaves as prayers developed and feast days accrued. (This happened, for example, in Paris, Bib. Ste Genevieve Ms. 97, where a fifteenth-century hand has added a text for the feast of St Elizabeth; Fig. 2). Students could react to the contents by drawing manicules or inscribing other comments in textbooks. Someone even added images of punishments to a fifteenth-century copy of Tractatus de Maleficiis, or Treatise on Evil Deeds.29 Owners could also take advantage of the blank areas in the book to add birth, death, and marriage information (which is often dated), to let a child use a blank page to practice writing ABCs, to make inventories or shopping lists. Thirdly, users could add physical material to the book, such as parchment paintings, additional leaves, or entire quires.30 They could glue or sew two-dimensional objects to its folios to transform it into a treasure chest. They could sew curtains above miniatures, to add a layer of ritual, to introduce more precious materials into the book, and to protect the image. Manuscripts with these sorts of additions often have other signs of wear, indicating many interactive events. Personal prayer books could serve as comfort objects with which the owner would spend considerable time, poring and lingering over the content, stroking and riffling the folios.

Fig. 2 Folio from a missal, with a Mass for St Elizabeth added in a fifteenth-century hand. Paris, Bibliothèque Sainte-Geneviève, Ms 97, fol. 241r. Cliché: IRHT-CNRS

Someone who handles a book frequently is likely to use it in multiple ways, adding images, texts, and physical material, not to mention grime and fingerprints. Thus, the dates of additions often coincide with periods of heavy use. In the case of Ms. Lat. Liturg. d. 7 (discussed below; see Figs 4–5), the damage must be medieval, because it pre-dates the medieval repair. And the damage from use coincides with the textual additions, which are made in a late medieval hand. In some manuscripts that bear needle holes from now-missing curtains above miniatures, the curtains may have been added as a response to partial damage of the book through touching: a protective textile, it was calculated, would prevent further damage. Those who used their books intensively and frequently also caused damage to the books’ spines, which afforded them the opportunity to incorporate new images and quires at rebinding. Many medieval manuscripts in pre-modern bindings are often in their second or third binding. Rebinding often coincides with, or immediately follows, an intense period of use.

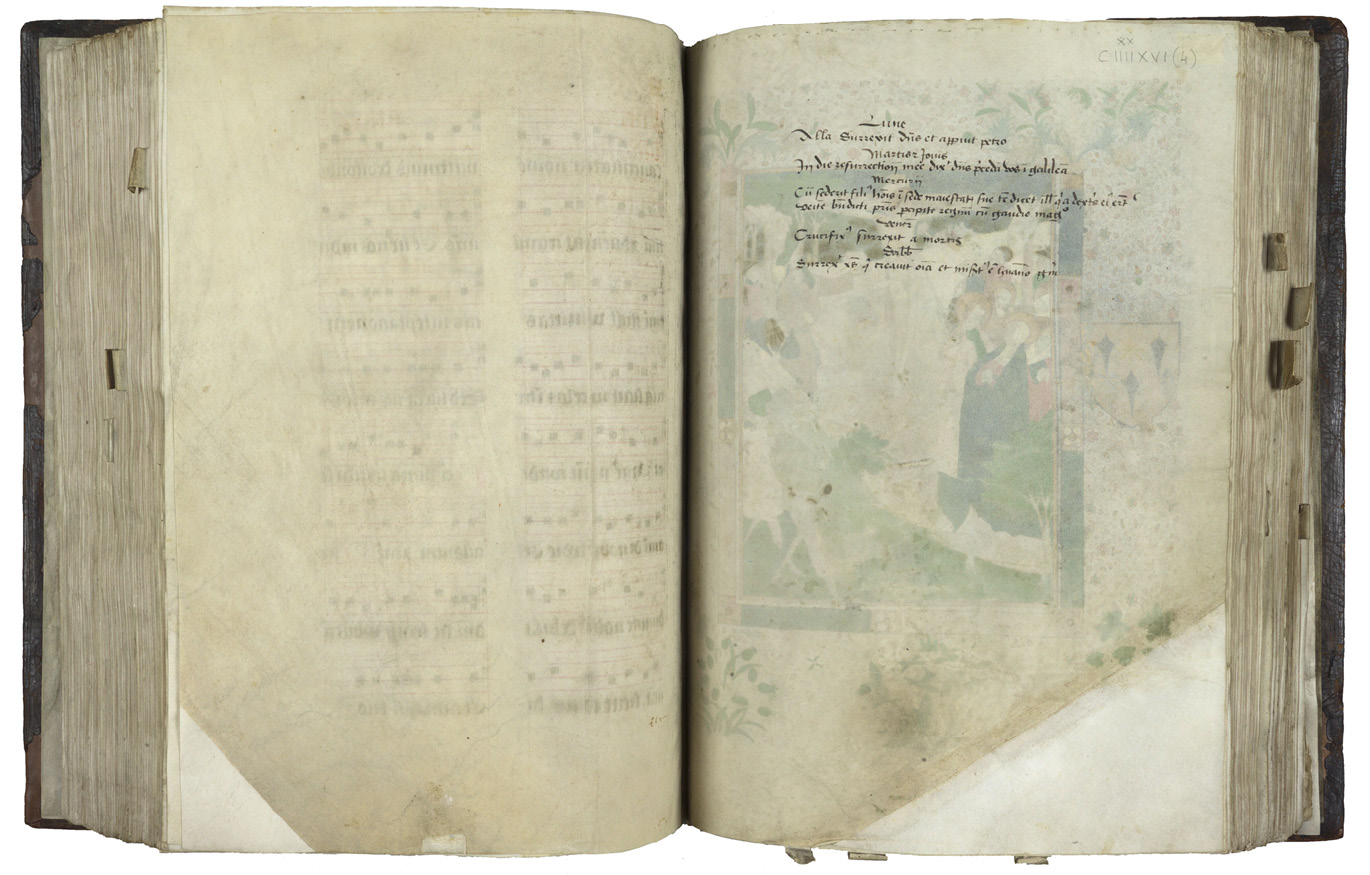

In the case of the missal for Angers mentioned above, it may have been bishop Jean Michel who wrote notes on the blank back of the Crucifixion, detailing how to acknowledge the Passion for each day of the week (Angers, Archives départementales de Maine-et-Loire, J[001] 4138, fol. 196r, Fig. 3). Jean Michel, or whoever wrote the instructions, considered the manuscript a utilitarian object that would help him to carry out the celebration and enactment of the death and resurrection of Jesus over a series of days. These added notes—plus the grime on many of the book’s lower corners and the targeted touching of the illuminations of Christ Crucified and God Enthroned—help to build a coherent use-wear portrait of the manuscript, which coalesces around the added script, and which is typical of a mid-fifteenth-century hand.

Fig. 3 Opening in a missal for the Use of Angers, before the Canon, 1439(?). Angers, Archives départementales de Maine-et-Loire, J(001) 4138, fols 195v-196r. Cliché: IRHT-CNRS

Because scripts change over time, most readers could not read old manuscripts without specialized training. Proponents of Carolingian script attempted to overcome this problem by imposing a script designed to be pan-European and standardized, but even that failed. Consider the Aratea manuscript in Leiden University (Ms. Voss. lat. Q. 79), an astrological text written in the ninth century based on a Hellenistic Greek source. Although it was copied in clear Carolingian rustic capitals with few abbreviations and regular spacing, someone in the thirteenth century apparently could not easily read the script and therefore felt the need to re-transcribe all the texts in a gothic hand in the margins, with even wider spaces between letters, but using capital and lower-case letters.31 This implies that older manuscripts would have limited utility as readable documents, outside a circumscribed group of scholars. It seems likely, then, that scripts remained in regular circulation for only a short period, and that regular lay book readers would not necessarily be able to read much earlier scripts. People who used manuscripts to access their texts either did so close to the time when they were made or else were trained for that task.

Third, the person most receptive to the content and design choices found within a particular manuscript is the one who commissioned it. The default here is that most wear by abrasion happens during a manuscript’s period of highest functional utility, early in its existence. In other words, utility correlates with tactility.32 However, in cases studied here, I note instances in which the date of the damage is especially ambiguous or unknowable.

In his Making and Effacing Art, Philip Fisher articulates a shift in handling and display as an object moves from utilitarian value to museum value. Taking an ancient sword as an example, Fisher considers its original function in the hands of the warrior who wields it in battle. After the warrior’s death, the sword becomes a sacred object that will “summon and transmit the spirit of the warrior,” but is used only in ceremonies (such as healing rituals) that might involve touching the sword.33 After the society suffers defeat and the sword becomes part of the booty acquired by the victors, it becomes an object of wealth, and concomitant with this function, it is suitably displayed. In each of these contexts, the sword has meaning in a community of objects, first clustered with shields and protective gear in its warrior context; then alongside priestly costumes in its sacred context; and eventually with jewels and carpets in its treasure context. In a final stage, a new civilization appropriates the sword and puts it in a museum, where it is classified and preserved. In this context, it is studied and compared with other examples, which represents a fourth kind of “cultural heritage” value.34

Such shifting values apply not only to hypothetical swords, but also to real manuscripts. Over time, the function of many medieval books changed, often from utility to nostalgia. In the case of prayer books, owners might continue to use a book to record birth, death, and marriage information even if they retire it from daily ritual devotion. The prayer book could become an heirloom and family record. Whether later family members still used it as a prayer book would depend on their abilities to read the antiquated script, and whether a shift in devotional habits had rendered it obsolete. Later, it might become an object of historical and monetary value to a modern collector, such as Harley, Morgan, or Getty, or a European royal family, and from there enter a museum or national library, where preservation might be paramount, but other values—such as displaying industrialists’ wealth or promoting national pride—might also operate. In this model, the bulk of the use-wear—which is related to its religious or performative functions—will have occurred early in an object’s history.

One could point to exceptions to this trend: namely, manuscripts that were degraded in the modern era by post-medieval collectors. One can think of the illuminated volumes that were dismantled to be mounted in albums, manuscripts left in display cases until their bindings froze open, and manuscripts pawed by generations of cultural tourists. One would not be surprised if such handlers skipped the text pages and turned straight to the pictures, just as modern viewers might do when leafing through a digital version of a manuscript posted online. The most celebrated manuscripts often attract the most attention, and that very attention leads to their degradation. Although I remain cognizant of these forms of modern degradation, they are not my subject in this study. The wear I am interested in studying occurred in the pre-modern period, when the bulk of the utility-motivated damage took place.

Certain book types had more stability and therefore longevity than others: a thirteenth-century Paris Bible could stay relevant for centuries, because the text did not change, and its readers would have been learned men who could navigate the highly abbreviated and diminutive Gothic script. In contrast, a missal might well become obsolete when new feasts came into existence; up to a certain point, clerics could inscribe new feasts on the empty pages at the end of the book to keep the manuscript up to date. As long as additions were being made, the book was presumably still in use. Events including the Protestant Reformation created situations in which some books quickly lost their ritual relevance but took on historical value, if they were kept at all. Inversely, manuscripts collected for their historical value lose their utilitarian value. The more collectors value a book as a “museum piece,” the less they want to risk damaging the painting (although cutting the painting out altogether was not always seen as damaging the book, but as a means of preserving and displaying the illumination). If manuscripts generally moved along a continuum from utility when they were new, to preservation when they were old, then it is reasonable to propose that most of the utility-related marks of wear were incurred early in books’ histories.

A significant exception to this model is the Gospel manuscript. Because the text was considered to have been written by the Four Evengelists, it did not change. Unlike other book types, it could have a very long career without growing obsolete: no new feasts, prayers, or laws needed to be added to it. Insofar as it served as a symbol of the Word of God, the Gospel manuscript had many roles for which it did not need to be read. For that reason, its antiquated script did not render it illegible, for its legibility was not required. On the contrary, an antiquated script and decoration could render it more powerful, closer to the origin. Gospel manuscripts could be made for a monastic library as a book to study, but that is not the concern of the current investigation. What interests me are Gospel manuscripts made for the altar, to fulfill a role in a performance. As altargoods, they could have a function more like relics than other books had, as discussed below in Chapters 3 and 4.

In light of the progressive resocialization of most books (except Gospel manuscripts), consider the shifting functions of medieval manuscripts: when new, they provided text to read and images to gaze upon. They were designed for immediate and compelling needs, often to the specifications of a particular recipient. As hand-crafted objects, they were not designed for the use of subsequent owners, although later owners could upgrade and personalize them. My previous work on use-wear analysis suggests that second owners who upgraded manuscripts paid most attention to the very sections that they had added themselves.35 That stands to reason, since those added sections represented items that owners so fiercely desired that they were willing to go to great lengths to have the new parts added. Adding a quire, for example, would entail obtaining the parchment, hiring a scribe, incorporating the new material and rebinding the entire book. It is no wonder that added sections are often the most heavily thumbed.

All of this raises several questions. How did different forms of handling manifest on the page? How can one distinguish forms of handling to make this a useful category of historical inquiry? In what ways can signs of wear—and not just words, images, and decoration on the page—be legible and interpretable? In order to consider these questions, I distinguish among categories of damage by producing a typology, because creating new knowledge depends upon noticing patterns and forging categories for understanding. Some examples that follow exhibit patterns of wear wrought by regular, hard use. These patterns are different from the abrasion incurred when users purposely touched specific passages of ink, paint, or parchment. The typology I propose will, I hope, bring clarity to a complex field of analysis, allow one to gain some control over it, and lead to narratives about the handling of books by medieval users that make internal sense within individual book-objects and across groups of books.

1 Angers, Archives départementales de Maine-et-Loire, Ms. J(001) 4138, Fol. 196v (quater)-197r (quinquies). Since the foliation misses the entire canon, these folios are referred to as 196, 196bis, 196ter, 196quater, 196quinquies, 197, etc. It has been fully digitized: https://bvmm.irht.cnrs.fr/mirador/index.php?manifest=https://bvmm.irht.cnrs.fr/iiif/1334/manifest. Its bibliography is maintained here: http://initiale.irht.cnrs.fr/codex/5771

2 The manuscript was exhibited in Anjou—Sevilla. Tesoros de arte, Exposicion organizada por la Comisaria de la Ciudad de Sevillla para 1992 y el Conseil Général de Maine-et-Loire, Real Monasterio de San Clemente, 25 de Junio2 de Agosto (Tabapress, 1992).

3 Literature about the stakes of digitizing medieval manuscripts grows weekly. For a recent perspicacious study, see Johanna Green, “Digital Manuscripts as Sites of Touch: Using Social Media for ‘Hands-On’ Engagement with Medieval Manuscript Materiality,” Archive Journal (September 2018). http://www.archivejournal.net/?p=7795.

4 The current study expands my earlier work on this topic: see Kathryn Rudy, “Dirty Books: Quantifying Patterns of Use in Medieval Manuscripts Using a Densitometer,” Journal of Historians of Netherlandish Art, 2.1 (Summer, 2010), and idem, “Kissing Images, Unfurling Rolls, Measuring Wounds, Sewing Badges and Carrying Talismans: Considering Some Harley Manuscripts Through the Physical Rituals They Reveal,” eBLJ special volume: Proceedings from the Harley Conference, British Library, 29–30 June 2009 (2011).

5 In building this argument, I am drawing on several important studies that interpret damage in manuscripts. Michael Camille did so in a sustained way in “Obscenity under Erasure: Censorship in Medieval Illuminated Manuscripts,” In Obscenity: Social Control and Artistic Creation in the European Middle Ages, edited by Jan M. Ziolkowski (Brill, 1998), pp. 139–54. Camille had also noted kissing as a ritual that degraded manuscripts, although he was more interested in theorizing (and dating) late medieval censorship. Gil Bartholeyns, Pierre-Olivier Dittmar, and Vincent Jolivet, “Des Raisons de Détruire une Image,” Images Revues 2 (2006), argue that the mechanisms for destroying an image in a manuscript could include iconoclasm, idolatry, the expunging of evil (which is distinct from iconoclasm), or repeated gestures. I agree and am expanding and further nuancing the categories. John Lowden has applied use-wear analysis in a brief but insightful article and acknowledged that lay people kissed manuscripts and rubbed images of saints, in his keynote address at the conference “Treasures Known and Unknown,” held at the British Library Conference Centre, 2–3 July 2007, British Library. Lowden paved the way in seeing certain forms of destruction as a legitimate form of use, rather than strictly censorship or iconoclasm. See also Erik Kwakkel, “Decoding the Material Book: Cultural Residue in Medieval Manuscripts” in The Medieval Manuscript Book: Cultural Approaches, eds. Michael Van Dussen and Michael Johnston (Cambridge University Press, 2015), pp. 60–76; although this text does not address use wear, it does show how codicological features can be read. Cormack Bradin and Carla Mazzio ask a similar set of questions of early modern printed books in Book Use Book Theory 1500–1700 (University of Chicago Library, 2005), http://pi.lib.uchicago.edu/1001/dig/pres/2011-0098.

6 Iconoclasm and allied forms of erasure have been treated elsewhere—by David Freedberg globally, and by Michael Camille and Horst Bredekamp for the medieval period: David Freedberg, The Power of Images: Studies in the History and Theory of Response (University of Chicago Press, 1989); David Freedberg, “The Fear of Art: How Censorship Becomes Iconoclasm,” Social Research 83.1 (2016), pp. 67–99; Michael Camille, “Obscenity under Erasure: Censorship in Medieval Illuminated Manuscripts,” in Obscenity: Social Control and Artistic Creation in the European Middle Ages, edited by Jan M. Ziolkowski (Brill, 1998), pp. 139–54; Horst Bredekamp, Kunst als Medium sozialer Konflikte: Bilderkämpfe von der Spätantike bis zur Hussitenrevolution (Suhrkamp, 1975). Although not specifically about iconoclasm, Madeline Harrison Caviness, Visualizing Women in the Middle Ages: Sight, Spectacle, and Scopic Economy (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2001) presents examples of erasure and censorship, treated from a feminist perspective, different from that of Camille. Scholars of Persian and Islamic traditions have noticed multiple and contradictory motivations for deliberately destroying images; see Christiane Gruber, “In Defense and Devotion: Affective Practices in Early Modern Turco-Persian Manuscript Paintings,” in Affect, Emotion, and Subjectivity in Early Modern Muslim Empires: New Studies in Ottoman, Safavid, and Mughal Art and Culture, edited by Kishwar Rizvi (Brill, 2017), pp. 95–123.

7 For a lively illustrated introduction, with further references, see Irene O’Daly, “Leiden, UB, GRO 22,” The Art of Reasoning in Medieval Manuscripts (Dec. 2020), https://art-of-reasoning.huygens.knaw.nl/gro22.

8 On Memory (Rhetorica novissima, VIII, 13), translated by Sean Gallagher in The Medieval Craft of Memory: An Anthology of Texts and Pictures, edited by Mary Carruthers and Jan M. Ziolkowski, p. 111.

9 Jan Assmann, Cultural Memory and Early Civilization: Writing, Remembrance, and Political Imagination (Cambridge University Press, 2011), esp. pp. 81–87.

10 Gustaaf Johannes Renier, History, Its Purpose and Method (Allen and Unwin, 1950), passim; Peter Burke, Eyewitnessing: The Uses of Images as Historical Evidence (Cornell University Press, 2001, reprinted 2008), p. 13 and passim, draw on these ideas. Ann-Sophie Lehmann, “Taking Fingerprints: The Indexical Affordances of Artworks’ Material Surfaces,” in Spur der Arbeit: Oberfläche und Werkprozess, edited by Magdalena Bushart and Henrike Haug (Böhlau Verlag, 2018 (2017)), pp. 199–218, demonstrates why surfaces and fingerprints are essential to forging and understanding meaning.

11 Pallasmaa has written about the dire implications of non-organic building materials in modern architecture: Juhani Pallasmaa, The Eyes of the Skin: Architecture and the Senses (Academy Editions, 1996); The Thinking Hand: Existential and Embodied Wisdom in Architecture (Wiley, 2009).

12 This study joins others in interpreting medieval objects through their materials. See Lorraine Daston, Things That Talk: Object Lessons from Art and Science (Zone Books, 2008); Caroline Walker Bynum, Christian Materiality: An Essay on Religion in Late Medieval Europe (Zone Books, 2011); Martha Rosler et al., “Notes from the Field: Materiality,” The Art Bulletin 95.1 (2013), pp. 10–37; Christy Anderson, Anne Dunlop, and Pamela H. Smith, eds, The Matter of Art Materials, Practices, Cultural Logics, c.1250–1750 (Manchester University Press, 2016). According to James Elkins, “It is one of the common self-descriptions of art history that it pays attention to materiality, to the embodied, physical presence of the artwork. But it only does so in a limited way… [M]ost texts on painting written by art historians treat pictures as images,” From James Elkins, “On Some Limits of Materiality in Art History,” 31: Das Magazin des Instituts für Theorie [Zürich] 12 (2008), pp. 25–30.

13 Kathryn M. Rudy, “Dirty Books: Quantifying Patterns of Use in Medieval Manuscripts Using a Densitometer,” Journal of Historians of Netherlandish Art 2.1(2010).

14 Rachel Fulton, “Taste and See that the Lord is Sweet’ (Ps. 33:9): The Flavor of God in the Monastic West,” The Journal of Religion 86.2 (2006), pp. 169–204. The Sensory Turn has made inroads in manuscript studies, as evidenced by Theresa Zammit Lupi, “Books as Multisensory Experience,” Tracing Written Heritage in a Digital Age, edited by Ephrem Ishac, Thomas Casandy and Theresa Zammit Lupi (Harrassowitz, 2021), pp. 21–31. For the development of the sensory turn in the humanities, see Richard G. Newhauser, “The Senses, the Medieval Sensorium, and Sensing (in) the Middle Ages,” in Handbook of Medieval Culture (Vol. 3), edited by Albrecht Classen (De Gruyter, 2015), pp. 1559–75.

15 For an excellent overview of the understanding of the senses in the middle ages, see the introductory essay by Fiona Griffiths and Kathryn Starkey in the volume they co-edited: Sensory Reflections: Traces of Experience in Medieval Artifacts (De Gruyter, 2018). https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110563443. As Bernard of Clairvaux discusses (and as the essays in this volume show), the five corporeal senses were joined by five spiritual senses. Medieval people would have experienced objects with a combination of all ten senses.

16 Exceptions include rituals in which the book remains closed, as discussed by Eyal Poleg, “The Bible as Talisman: Textus and Oath-Books,” in Approaching the Bible in Medieval England (Manchester Medieval Studies) (Manchester University Press, 2013), pp. 59–107.

17 For approaches to manipulable objects other than manuscripts, see Sarah Blick and Laura Deborah Gelfand, eds, Push Me, Pull You: Imaginative and Emotional Interaction in Late Medieval and Renaissance Art (2 vols) (Brill, 2011); and Adrian W. B. Randolph, Touching Objects: Intimate Experiences of Italian Fifteenth-Century Art (Yale University Press, 2014).

18 For an example of such an approach, applied to stone objects made 6000 years ago, see Richard Fullagar and Rhys Jones, “Usewear and Residue Analysis of Stone Artefacts from the Enclosed Chamber, Rocky Cape, Tasmania,” Archaeology in Oceania 39, 2 (2004), pp. 79–93. Archeologists continue to explore how materials affect cognition; see Lambros Malafouris, How Things Shape the Mind: A Theory of Material Engagement (MIT Press, 2013).

19 Anthony Cutler, The Hand of the Master: Craftsmanship, Ivory, and Society in Byzantium (9th-11th Centuries) (Princeton University Press, 1994), esp. pp. 23–25, 29. Considering signs of wear in ivories as clues to their original function has an older scholarly tradition: Louis Serbat, “Tablettes à écrire du XIVe siècle,” Mémoires de la Société nationale des Antiquaires de France 73 (1913, published 1914), 301–13, p. 309, notes that the detached pages of an ivory booklet were once connected, as one can see from signs of abrasion caused by the thong hinges.

20 Paul Connerton, How Societies Remember (Cambridge University Press, 1989).

21 J. L. Austin, How to Do Things with Words, The William James Lectures (Clarendon Press, 1962).

22 Reprinted in Marcel Mauss, “Techniques of the Body,” in Incorporations, edited by Jonathan Crary and Sanford Kwinter (Zone, 1992), pp. 455–77.

23 Joyce Coleman defines and discusses the term prolector in Public Reading and the Reading Public in Late Medieval England and France (Cambridge University Press, 1996).

24 Doctors created mobile spaces of authority when, during consultations with patients, they handled almanacs, phlebotomy and urine charts, and other accoutrements that demonstrated their mastery of medical and astronomical knowledge. I have not been able to demonstrate that their patients copied doctors’ gestures in their own books, although they may have done so, especially since calendars, zodiacal diagrams, and lists of Egyptian days are sometimes copied into private prayer books. See Karen Eileen Overbey and Jennifer Borland, “Diagnostic Performance and Diagrammatic Manipulation in the Physician’s Folding Almanacs,” in The Agency of Things in Medieval and Early Modern Art: Materials, Power and Manipulation, edited by Grazyna Jurkowlaniec, Ika Maryjaszkiewicz and Zuzanna Sarnecka (Routledge, 2018), pp. 144–56.

25 Robert S. Nelson, “The Discourse of Icons, Then and Now,” Art History 12 (1989), pp. 144–57, shows how images in manuscripts project into, and interact with, the viewer, who sometimes kisses them.

26 The medieval liturgical scholar William Durandus (1230–1296) lists the biblical injunctions against image-making. See The Rationale divinorum officiorum of William Durand of Mende: A New Translation of the Prologue and Book One, trans. Timothy M. Thibodeau (Columbia University Press, 2007), pp. 32–33.

27 Important work has been written about illuminations of St Margaret that have been touched violently, including: Jennifer Borland, “Violence on Vellum: St. Margaret’s Transgressive Body and Its Audience,” in Representing Medieval Genders and Sexualities in Europe: Construction, Transformation, and Subversion, 600–1530, edited by Elizabeth L’Estrange and Alison More (Ashgate, 2011), pp. 67–87; Josepha Weitzmann-Fiedler, “Zur Illustration der Margaretenlegende,” Münchner Jahrbuch der bildenden Kunst 3.17 (1966), pp. 17–48. See also John Lowden’s web-published lecture, “Treasures Known and Unknown in the British Library,” particularly the section on the Passio of St Margaret (https://www.bl.uk/catalogues/illuminatedmanuscripts/TourKnownB.asp).

28 Michael Camille writes: “The number of times one comes across erasure of male and female genitals in manuscripts suggests that it was a widespread phenomenon in the later Middle Ages, that is, sometime in the period when these images were still circulating as functional objects and before they became collectable curiosities or valuable works of art in the nineteenth century,” in “Obscenity Under Erasure: Censorship in Medieval Illuminated Manuscripts,” Obscenity: Social Control and Artistic Creation in the European Middle Ages, edited by Jan M. Ziolkowski, pp. 139–54 (Brill, 1998), at p. 147.

29 Philadelphia, Free Library of Philadelphia, Rare Book Department, LC 14 23. See Kathryn M. Rudy, “Adding Images to the Book as an Afterthought,” Reactions: Medieval/Modern, edited by Dot Porter (University of Pennsylvania Libraries, 2016), pp. 31–42. Erik Kwakkel’s essay in this volume, “Filling a Void: The Use of Marginal Space in Medieval Books,” pp. 19–28, presents fascinating examples of written additions.

30 For parchment paintings—that is, independent sheets added later to manuscripts—see Kathryn M. Rudy, Postcards on Parchment: The Social Lives of Medieval Books (Yale University Press, 2015).

31 Ranee Katzenstein and Emilie Savage-Smith, The Leiden Aratea: Ancient Constellations in a Medieval Manuscript. (J. Paul Getty Museum, 1988), pp. 6–7. Erik Kwakkel makes the point that certain readers preferred certain scripts and had difficulty deciphering others in: “Decoding the Material Book: Cultural Residue in Medieval Manuscripts,” The Medieval Manuscript Book: Cultural Approaches, eds. Michael Van Dussen and Michael Johnson (Cambridge University Press, 2015), pp. 60–76, at p. 69.

32 I owe this phrase to Erik Inglis.

33 Philip Fisher, “Art and the Future’s Past,” in Making and Effacing Art: Modern American Art in a Culture of Museums (Harvard University Press, 1991), p. 5.

34 ibid, p. 5.

35 Kathryn Rudy, Piety in Pieces: How Medieval Readers Customized Their Manuscripts (Open Book Publishers, 2016), p. 203 and passim, https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0094.